Historical Studies

Air Force

SAF/AA

A History of tHe office of tHe AdministrAtive AssistAnt

to tHe secretAry of tHe Air force

PriscillA d. Jones And KennetH H. WilliAms

cover

An undated aerial view of the Pentagon from the Potomac River side, by TSgt. Andy Dunaway,

USAF. Library of Congress.

Air Force

Historical Studies

U.S. Air Force Historical Support Division

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

2019

SAF/AA

A History of tHe office of tHe AdministrAtive AssistAnt

to tHe secretAry of tHe Air force

Priscilla D. Jones

and

Kenneth H. Williams

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within

do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department

of Defense, or the U.S. government. All documents and publications

quoted or cited have been declassied or originated as unclassied.

contents

PArt one

The Origins of the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant, 1947–1986

Kenneth H. Williams 1

PArt tWo

The Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the

Air Force: Goldwater-Nichols and Beyond

Priscilla D. Jones 23

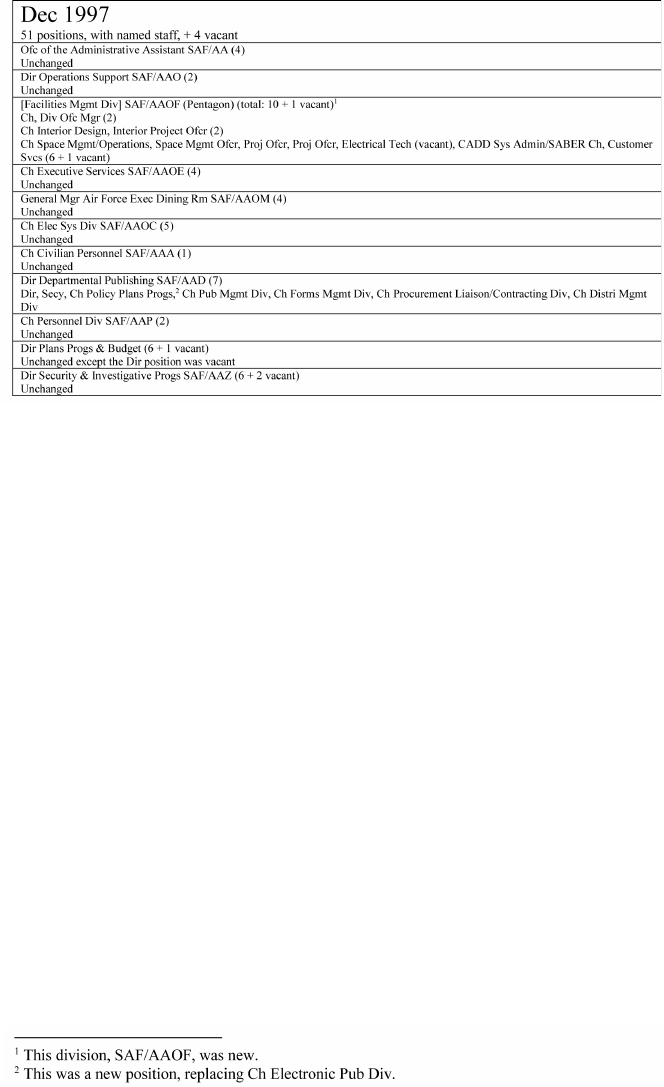

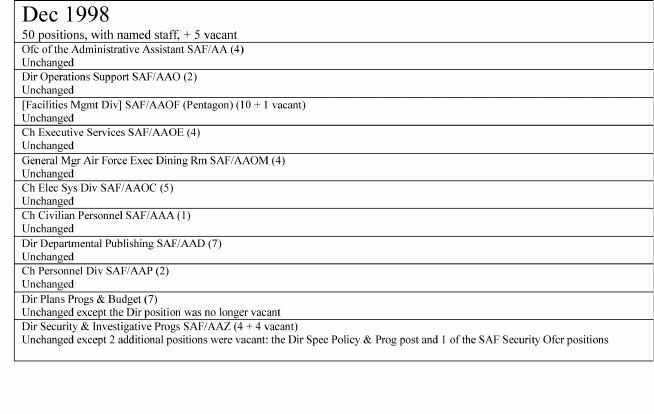

sAf/AA orgAnizAtion tAbles 76

AdministrAtive AssistAnts to tHe

secretAries of tHe Air force

John J. McLaughlin

September 27, 1947 – October 4, 1963

Joseph P. Hochreiter (acting)

October 5, 1963 – February 16, 1964

John A. Lang Jr.

February 17, 1964 – August 18, 1971

Thomas W. Nelson (acting)

August 19, 1971 – September 28, 1971

Thomas W. Nelson

September 19, 1971 – January 11, 1980

Robert W. Crittenden (acting)

January 12, 1980 – August 24, 1980

Robert J. McCormick

August 25, 1980 – March 31, 1994

William A. Davidson (acting)

April 1, 1994 – June 14, 1994

William A. Davidson

June 15, 1994 – September 30, 2011

Timothy A. Beyland

October 1, 2011 – May 2, 2014

Patricia J. Zarodkiewicz

May 3, 2014 – Present

1

Part One

The Origins of the Ofce of the

Administrative Assistant, 1947-1986

Kenneth H. Williams

The roles and responsibilities of the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

to the Secretary of the Air Force have evolved exponentially since the rst

secretary, W. Stuart Symington Jr., established it. On September 27, 1947,

nine days after the founding of the service, Symington assigned twenty-

eight-year-old John J. McLaughlin, on an interim basis because there

was no funding for additional personnel, to coordinate “housekeeping”

services such as correspondence control and stang. This study outlines

the origins and development of the roles of the administrative assistant, the

oce that is known as SAF/AA, from the founding of the Air Force up to

the time of the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, better

known as Goldwater-Nichols.

1

When the National Security Act of 1947 (Public Law 253) created

the Air Force, the “new” service was not new at all, as the U.S. Army Air

Forces and its preceding iterations had existed for forty years. Neither was

the concept of an administrative assistant, as both the War Department and

the Department of the Army had oces with similar duties, which will be

discussed below. There was a tremendous amount to be done to transition

to an independent service—scheduled to take two years as the Army

passed responsibilities and facilities to the Air Force—but the key leaders

remained the same.

2

Symington, who had been assistant secretary of war

for air, became the rst secretary of the Air Force, and the commanding

general of the Army Air Forces, Gen. Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz, transitioned

to the role of Air Force chief of sta. Although President Harry S. Truman

The author thanks colleagues Jean A. Mansavage, Priscilla D. Jones, Yvonne A. Kinkaid, Helen T. Kiss,

and William C. Heimdahl (AF/HO retired) for their research and editorial contributions to this study.

1. “Housekeeping” quote from “History of the Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force from September

18, 1947, to June 30, 1950,” 2 vols., typescript, AF/HOH, 1:3 (hereafter OSAF history, 1947–50).

2. For a detailed study of the origins of an independent Air Force, see Herman S. Wolk, Planning

and Organizing the Postwar Air Force, 1943–1947 (Washington, DC: Oce of Air Force History,

1984). According to Wolk (pp. 203–4), as of September 1947, the Oce of the Secretary of the Air

Force “inherited solely those functions of the Secretary of the Army as were then assigned to or

under the control of the Commanding General, Army Air Forces. Over two years the Secretary of

Defense was authorized to assign to the Department of the Air Force such other responsibilities of

the Department of the Army as he deemed necessary or desirable, and to transfer from the Army

appropriate installations, personnel, property, and records.” This book (pp. 275–92) also contains the

full text of the National Security Act of 1947.

2

had to formally appoint Symington to the newly created position, Secretary

of War Robert P. Patterson had put Symington on notice in April 1946 that

he would be overseeing the transition to an independent Air Force if one

did come to pass.

3

There were many new challenges for the Air Force secretariat as of

September 1947, as it had to build its own headquarters support sta and

infrastructure and choose how much it would continue to follow Army and

Army Air Forces protocols. One of Symington’s formative decisions was

to continue the division of labor between operations and administrative

support that had evolved under Robert A. Lovett while Lovett was assistant

secretary of war for air in the early 1940s. Symington and Spaatz reached

an understanding that Symington would be the public spokesman for the

Air Force in interactions with Congress and the president but that he and

his sta would not be directly involved in operational details.

4

Truman had summoned Symington into government service in

1945 from Emerson Electric, where Symington had been company

president. Symington brought business acumen to the job as well as

experience with the military acquisitions process, as Emerson Electric

had manufactured gun turrets for bombers during World War II. In fact,

Symington had rst met Truman when then-Senator Truman (D-Mo.) led

an investigation of Emerson’s contracting practices. The Senate committee

cleared Emerson, but from the process, Symington gained an understanding

of how Congress viewed acquisitions, as well as a champion in Truman,

who asked Symington to head the Surplus Property Board the same week

Truman became president in April 1945.

5

To understand how the roles of the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant originated and initially evolved, one must appreciate how

business-oriented the founding Air Force leadership was. Symington had

served as president of a manufacturing company and believed strongly in

scientic management and eciency principles. Arthur S. Barrows, the

rst under secretary of the Air Force, had recently retired as president of

3. James C. Olson, Stuart Symington: A Life (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003),

87. There is some indication that even though the rst secretary of defense, James V. Forrestal, was

a long-time friend of Symington’s that Symington was not his rst choice to be secretary of the

Air Force. Truman overruled Forrestal and appointed the fellow Missourian. Wolk, Planning and

Organizing the Postwar Air Force, 178, 183.

4. Warren A. Trest and George M. Watson Jr., “Framing Air Force Missions,” in Winged Shield,

Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force, ed. Bernard C. Nalty (Washington, DC: Air

Force History and Museums Program, 1997), 1:400; George G. Watson Jr., The Oce of the Secretary

of the Air Force, 1947–1965 (Washington, DC: Center for Air Force History, 1993), 53. Watson’s

book is the authoritative study of the origins and development of the Oce of the Secretary. The only

administrative assistant Watson mentions, however, is John McLaughlin, who served for most of the

period covered in the book.

5. Olson, Symington, 50–59.

3

Sears, Roebuck and Company, one of the leading retailers in the United

States. Symington had known Barrows since the early 1930s. Assistant

Secretary Cornelius Vanderbilt “Sonny” Whitney, scion of two prominent

American industrial families and a cousin of Symington’s wife, had founded

a mining company, provided signicant initial investment in the company

that became Pan American World Airways, and backed everything from

movies—including Gone with the Wind—to thoroughbreds. Whitney had

own in both world wars and had served on Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s

sta during World War II as a colonel in the Army Air Forces. The other

assistant secretary was Eugene M. Zuckert, who had degrees from Yale

Law School and Harvard Business School, where he had taught. Zuckert

had worked as an assistant to Symington at the Surplus Property Board

and while Symington was assistant secretary of war for air.

6

There is signicant information available on these men of prominence

Symington assembled to mold the Air Force like a business.

7

Much less is

known about John McLaughlin, a young man from Brooklyn, New York,

to whom these senior leaders turned to manage the nuts and bolts of their

everyday administrative duties. McLaughlin would become one of the

most vital threads of cohesion and continuity in the secretary’s oce, as

he served sixteen years as the rst administrative assistant to the secretary.

McLaughlin was born in 1919 and came to Washington in January 1940

for a civilian job in personnel with the Army Air Corps. He served with

the Navy on a submarine in the Pacic during World War II and returned

to his post with the Army Air Forces after the conict. On September 27,

1947, nine days after Symington took oce, the new secretary detailed

McLaughlin, on an interim basis, to oversee what were described as

“housekeeping” services.

8

The concept of an administrative assistant was not a new one for

the sta transitioning from what had been the War Department to the

6. Trest and Watson, “Framing Air Force Missions,” 1:400; Olson, Symington, 123; Joseph Durso,

“C. V. Whitney, Horseman and Benefactor, Dies at 93,” New York Times, December 14, 1992; Richard

Pearson, “Air Force Secretary Eugene Zuckert Dies,” Washington Post, June 6, 2000.

7. For Symington’s eorts to run the Air Force like a business, see in particular Wyndham Eric Whynot,

“Architect of a Modern Air Force: W. Stuart Symington’s Role in the Institutional Development of the

National Defense Establishment, 1946–1950” (PhD diss., Kent State University, 1997). Symington’s

signature phrase during the early days of the Air Force was “management control through cost control.”

Eugene Zuckert later conceded that “I never knew what it meant,” although he thought the saying

was “very shrewd, because he [Symington] was attempting to build the businesslike image of the Air

Force.” The early organizational charts even listed “Management Control” and “Cost Control” as

areas of responsibility for Zuckert as assistant secretary. Eugene M. Zuckert, interview with George

M. Watson Jr., December 3, 4, 5, 9, 1986, typescript, AF/HOH, 18–19 (hereafter Zuckert interview);

Jacob Neufeld, comp., Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force Organizational and Functional Charts,

1947–1984 (Washington, DC: Oce of Air Force History, 1985).

8. “John J. McLaughlin Dies; Aide to AF Secretaries,” Washington Post, April 18, 1972;

OSAF history, 1947–50, 1:3.

4

Department of the Air Force. There had been a similar position in the

Oce of the Secretary of War since its establishment in 1782, and one

had evolved in the Oce of the Secretary of the Army as well. By World

War II, the administrative assistant for the Army was overseeing records

management, personnel, contingency spending, civilian medical treatment,

printing, and procurement and accounting within the secretariat.

9

McLaughlin had to be detailed on interim status because the National

Security Act made no provision to pay new personnel. The Air Force

reached agreement with the Army to transfer the full sta of what had been

the Oce of the Assistant Secretary of War for Air—eleven civilians and

four ocers—to the Air Force and to fund the positions for the rest of scal

year 1948. With no budget for any additional billets, Secretary Symington

sought help from General Spaatz, who allocated Air Sta funds to meet

the initial civilian stang needs. Phased transfer of more personnel from

the Department of the Army also began over subsequent months.

10

With at least some personnel funding nally in place, Symington

regularized the Air Force’s new position of administrative assistant

on December 14, 1947. At that time, McLaughlin had a staff of three

civilians, one ocer, and one warrant ocer. In addition to the Oce of

the Administrative Assistant, Symington also established the oces of the

general counsel, legislative liaison, and information services.

11

During Symington’s tenure as secretary, the administrative assistant’s

oce reported directly to the secretary’s executive ocer, who for most

of the period was Brig. Gen. John B. Montgomery. The second secretary,

Thomas K. Finletter, made the Oce of the Administrative Assistant a

separate entity within the secretariat in October 1950, with the administrative

assistant reporting to the secretary through the under secretary.

12

9. Historical Support Branch, U.S. Army Center of Military History, “Quiet Service: A History

of the Functions of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army, 1789–1988,”

unpublished typescript, n.d., AF/HOH, 1, 18–19. The Ocial Register of the United States does not

indicate that there was an administrative assistant position within the Oce of the Assistant Secretary

of War for Air. During World War II, there had been a Management Control oce under the Air

Sta that seems to have approximated several of the functions of what became the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant. Branches of the Management Control oce were Administrative Services,

Organizational Planning, Operations Analysis, Manpower, Statistical Control, and Air Adjutant

General. Military ocers headed all of these sections. Air Force, January 1944, 33.

10. U.S. Air Force, Report of the Secretary of the Air Force to the Secretary of Defense for the

Fiscal Year 1948 (1 July 1947–30 June 1948) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Oce,

ca. 1948), 279–80.

11. Wolk, Planning and Organizing the Postwar Air Force, 185; OSAF history, 1947–50, 1:3–4, 10;

“History of the Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, September 18, 1947, through June 30, 1950,”

typescript, National Archives, RG 340, entry P5, box 5, p. 65 (hereafter OSAF history, 1947–50 [NA]).

12. “History of the Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 1 July 1950–30 June 1951,” draft,

typescript, AF/HOH, 12, 23 (hereafter OSAF history, 1950–51); Neufeld, Oce of the Secretary of the

Air Force Organizational and Functional Charts; OSAF history, 1947–50 (NA), 62. Before Air Force

independence, while Symington was still assistant secretary of war for air, he had sent then-Colonel

Montgomery to the United Kingdom to meet with senior ocials of the Royal Air Force and learn from

their experience as an autonomous air service. Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 47.

5

McLaughlin headed the Oce of the Administrative Assistant through

1963, serving seven secretaries of the Air Force, and was a signicant gure

in the formation and early development of the Air Force as an independent

service. Zuckert observed in a 1986 interview that McLaughlin was “a

darn good bureaucrat” who “knew where all the bodies were hidden.”

McLaughlin wrote in a 1962 article that in the late 1940s, a “small, closely knit

organization” managed the Department of the Air Force “with a minimum

of paperwork.” Secretary Symington emphasized four basic concepts:

functionality, exibility, decentralization, and simplicity. According to

McLaughlin, Symington had a “special ‘in the family’ camaraderie” with

General Spaatz and his successor, Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, that facilitated

coordination between the administrative and operational sides of the Air

Force. Nevertheless, Symington was a “dominant person,” as Zuckert put

it, and “everybody knew who was the boss.”

13

Symington assigned the Oce of the Administrative Assistant a couple

of signicant tasks from the very beginning that it continues to perform

to the present: management of personnel and space allocation within the

secretariat. As a 1950 history of the founding period put it, “Since all

secretariat oces were established and organized at approximately the

same time or at close intervals of each other, the problem of space and

manning was urgent for each oce.” Stang positions was challenging, as

many people, both civilians and reservists, who had worked in government

during World War II had gone back to their home states. Zuckert recalled

that “we had people coming into big jobs in Washington after the war who

had never served in a top headquarters in their life.”

14

Because of the lack of budgeting for personnel at the time of Air Force

independence, as noted above, a 1948 report by the secretariat stated that

“the interim policy of the Secretary provided for the initial manning of

each oce on an extreme austerity basis, and operating policy was limited

to those areas which could not be delegated to appropriate sections” of

the Air Sta. Symington gave preferential status to the Directorate of

Public Relations, the Air Force Personnel Council, and the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant. McLaughlin’s background in personnel was

invaluable, as the task for him and his colleagues was extensive. By the end

of the scal year on June 30, 1948, stang for the secretariat stood at 318,

a quantum leap in eight months from the initial fteen people. Of these,

13. “John J. McLaughlin Dies”; Zuckert interview, 7 (6th quote), 8 (5th quote), 32 (1st and 2d

quotes); John J. McLaughlin, “Organization of the Air Force: A Revolution in Management,” Air

University Quarterly Review 13, no. 3 (Spring 1962): 5 (3d and 4th quotes).

14. OSAF history, 1947–50 (NA), 65 (1st quote); Zuckert interview, 19 (2d quote). As the 1950

paper put it, “Perhaps the greatest achievement of this oce [of the Administrative Assistant] was the

laying out and equipping of the oces of the secretariat. Next, of course, was the procurement, training,

and placement of the personnel necessary to round out each oce.” OSAF history, 1947–50 (NA), 66.

6

121 (sixty-eight civilian, fty-three military) came in phased transfers of

billets from the Department of the Army as the Air Force began picking up

more of the responsibilities previously carried out by the Army Air Forces,

while 197 (114 civilian, eighty-three military) held newly lled positions.

All of these people had to have places to work, which made the task of

space management nearly as challenging as that of stang.

15

In an administrative history of the first ten years of Office of the

Secretary, Harry M. Zubko, a long-time employee of the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant best known as the compiler of Current News,

wrote in 1957 that at the time of Air Force independence, the service

had taken “a fresh approach to the organization of the Secretariat and to

the problem of providing civilian control in a military establishment.”

Unstated was that budgetary constraints left Symington and his small sta

little choice but to innovate. According to Zubko, “Unlike the Army or

Navy, whose civilian managers employed extensive backup organizations

to gather information on which to base their decisions, the Air Force

adopted a concept of providing civilian policy guidance, with the military

Air Sta performing the operational details, making backup studies, and

developing recommendations.”

16

As a result of this approach, the Air Force had the smallest sta among

the three service secretariats, but also blurred lines of responsibility. In a

much more candid piece that he wrote after he retired, Zubko recalled that

in the early years, the Oce of the Secretary had “all kinds of organizational

problems” while “trying to adjust its sta to get out from under the Army and

do the military things.” He observed that “there was a lot of confusion about

who was responsible for what.” The civilians had no roles in operational

aairs, while the military side “had some partial responsibility and a lot

of interest in administrative matters.” Zubko credited Assistant Secretary

Zuckert, who stayed with the oce until February 1952, with working out

the “original ground rules” and soothing tensions among senior ocials

in the secretariat and on the Air Sta. Nevertheless, confusion about roles

and responsibilities continued well into the 1950s, issues that led to a

McLaughlin-directed study discussed below.

17

As McLaughlin and his small sta tried to gure out personnel and

space allocation puzzles in the early days of Air Force independence,

15. Report of the Secretary of the Air Force to the Secretary of Defense for the Fiscal Year 1948,

280–81.

16. “Administrative History of the Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force,” typescript, draft by

Harry M. Zubko, August 28, 1957, AF/HOH, p. 1 (hereafter OSAF history, 1957).

17. Harry M. Zubko, “Historical Notes Highlight Pentagon Players—Part 3,” Foresights and

Hindsights from Harry, June 22, 2017, http://foresightsandhindsights.blogspot.com/2017/06/historical-

notes-highlight-pentagon.html.

7

Secretary Symington assigned the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

another signicant function that it has continued to oversee to the present:

budgeting for the administration of contingency funds. McLaughlin

submitted his rst budget for the secretariat in November 1947, a document

that outlined spending for scal year 1949.

18

Another important duty for the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

was to coordinate paperwork. Maj. Robert W. Endsley, the rst deputy

administrative assistant, set up the Correspondence Control Branch to

maintain records across the secretariat and develop suspense follow-

up procedures. The operation began with only two mail clerks. The

branch received ocial status in December 1947 within the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant and employed six civilians.

19

The Oce of the Administrative Assistant also established a

central repository for classified documents, the Top Secret Control

Oce, in October 1947. The unit monitored all incoming and outgoing

correspondence of high classication and maintained special les for the

secretary’s use. The secretariat transferred the Top Secret Control Oce

from the administrative assistant to the executive oce in April 1949, but

the function reverted to the administrative assistant in 1951 in the form of

the Document Control Branch.

20

After President Truman approved the Air Force seal on November

1, 1947, Secretary Symington designated the administrative assistant

as custodian of the emblem. He charged McLaughlin’s office with

establishing regulations and procedures for its use and with axing the seal

to department documents as required. The seal’s rst ocial use occurred

on December 18, 1947, when McLaughlin axed it to the commissions of

Barrows, Whitney, and Zuckert.

21

With the Oce of the Administrative Assistant formally established

in December 1947, McLaughlin brought in a team of management experts

to review the component oces to determine their requirements. A study

conducted in January 1948 resulted in the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant organizing into the following branches: Supply, Civilian

Personnel, Military Personnel, Correspondence, and Oce Services. The

oce also had a mess ocer and a special projects ocer. The mess ocer

was the originator of what became known as Air Force Mess Number

18. OSAF history, 1947–50 (NA), 65.

19. Ibid.

20. OSAF history, 1947–50, 1:10–11.

21. Report of the Secretary of the Air Force to the Secretary of Defense for the Fiscal Year 1948,

282–83; OSAF history, 1947–50, 1:2–3, 11. Truman had named Symington, Barrows, Whitney,

and Zuckert on recess appointments in September, and the Senate did not formally approve their

nominations until December. Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 53.

8

One, now the Air Force Executive Dining Facility. As of 1948, the Oce

of the Administrative Assistant had an authorized strength of thirty-nine

civilians, four ocers, and seven enlisted airmen. At that time, however, it

had only been able to hire sixteen civilians.

22

The Oce of the Administrative Assistant functioned with these

branches for a year and half before McLaughlin reorganized the sta

in October 1949 to better meet the needs of the secretariat as they had

developed. Civilian and military personnel consolidated into a single

Personnel Branch, and the Supply Branch became the Services Branch,

which was responsible for supplies and communications. McLaughlin

eliminated the Oce Services Branch and parceled its functions between

the Personnel Branch and the newly created Management Branch. The

Management Branch reviewed and analyzed procedural problems within

the secretariat and produced studies as assigned on issues of budget,

personnel, and space allocation. At the time of the restructuring, the

Management Branch consisted of six civilians and one ocer.

23

When Thomas Finletter succeeded Symington as secretary of the Air

Force in April 1950, reorganization of the secretariat extended to the Oce

of the Administrative Assistant, which consolidated functions into three

branches: Management, Administrative Services, and Correspondence

Control. Administrative Services took on the personnel duties as well as

the budgeting of contingency funds. At the end of June 1950, total stang

for the Oce of the Administrative Assistant stood at fty-three civilians,

two ocers, and three enlisted airmen.

24

The Korean War, which began the same month, prompted rapid

expansion of the Air Force, which more than doubled the size of its

military force within two years.

25

As noted above, Secretary Finletter

made the Oce of the Administrative Assistant a separate oce within

the secretariat in October 1950, and the office underwent ongoing

reorganization to meet the increasing needs of the secretariat and the

service, evolving into seven branches during 1951: Correspondence

Control, Administrative Services, Supply (which separated from

Administrative Services in May 1951), Management, Security (stood up

in August 1951), Document Security, and Air Force Mess Number One. In

one year, stang for the Oce of the Administrative Assistant increased

from fifty-eight to 128, with seventy-nine civilians, nine officers, and

22. OSAF history, 1947–50, 1:12–13.

23. Ibid., 1:13–14.

24. Ibid., 1:14.

25. From July 1950 to July 1952, the Air Force personnel limit increased from 416,000 to 1,061,000,

and the number of wings grew from forty-two (forty-eight authorized) to ninety-ve. Watson, Oce

of the Secretary of the Air Force, 117; McLaughlin, “Organization of the Air Force,” 6.

9

forty enlisted airmen as of June 1951. Finletter also expanded the scope

of responsibility for the Office of the Administrative Assistant in the

spring of 1951 when he assigned McLaughlin and his sta to be available

to advise the under secretary and the assistant secretaries on all matters

under their respective jurisdictions.

26

Although civilian and military personnel recruitment and training

remained together under the Administrative Services Branch, the branch

split civilian and military personnel into separate sections to better meet the

exigencies of wartime expansion. These two sections recruited and trained

personnel for the secretariat, processed military assignments, promotions,

and eectiveness reports, secured travel orders, and maintained personnel

records and rosters.

27

The Management Branch analyzed procedural problems in the secretariat

and recommended reallocation of responsibilities to better meet stang

needs with available personnel. The branch prepared mobilization stang

plans, developed a succession list for key civilian positions, reviewed the

delegation of powers and responsibilities within the secretariat, developed

informational and functional charts, and wrote policies, procedures, and

administrative directives.

28

The new Security Branch formalized several duties that had not been

permanently assigned. It authenticated security clearances across the

secretariat, conducted security training, and monitored compliance with

security instructions. Prior to the formation of the branch, the Oce of

the Air Provost Marshal had issued security clearances for the secretariat.

The Security Branch also formed and equipped a security guard force,

which numbered thirteen air police guards by March 1952, all enlisted

airmen. The Security Branch did not remain under the administrative

assistant for long, however, as the secretariat transferred it to the Air Sta

in 1952. Nevertheless, the Oce of the Administrative Assistant remained

responsible for “security services” within the secretariat and with advising

departments on security matters, although it did not have a branch devoted

to these issues again until the 1980s.

29

26. OSAF history, 1950–51, 23, 25; “History of the Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force from

April 1, 1951, to June 30, 1951,” 2 vols., 1:4, AF/HOH. It is interesting that so much reorganization

took place under Finletter, who Zuckert said was “not concerned with the business management of the

Air Force.” Zuckert interview, 8.

27. OSAF history, 1950–51, 24.

28. Ibid., 26.

29. OSAF history, 1950–51, 27–28; Department of the Air Force, “Department of the Air

Force Organization and Functions (Chartbook),” Headquarters Pamphlet 21-1, October 1960, vii

(quote) (hereafter Chartbook [date]); Office of the Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel

Telephone Directory, January 22, 1952, p. 4; Department of Defense Telephone Directory,

December 1987, O-148. All directories cited here and below can be found in the AF/HOH library.

10

Air Force Mess Number One was a self-supporting mess that catered

to the secretary and under secretary of the Air Force, the Air Force Chief of

Sta, and their invited guests. The Oce of the Administrative Assistant

had a mess ocer from at least January 1948, and there seems to have

been a formal mess for the secretary by 1950. The mess expanded under

Secretary Finletter and had grown to a sta of twelve by mid-1952.

30

Reorganization continued in 1952, both within the Office of the

Administrative Assistant and across the secretariat. McLaughlin rolled

administrative functions into an Administrative Services Division, which

included the Personnel and Services Branch, the Supply and Equipment

Branch, and Air Force Mess Number One.

31

An Administrative Management Division briey existed for the rst

part of 1952. It included Correspondence Control, which McLaughlin

broke out as a separate division by September 1952; the Management

Branch, which remained as the Management Oce through mid-1953

before it disappeared, its functions absorbed by other oces; and the

Security Branch, which the secretariat transferred to the Air Sta in

1952, as noted.

32

As Correspondence Control became a division, it initially included a

Document Security Branch and a Correspondence Control Branch, which

became the Mail and Records Branch in 1953 and then separated into a

Mail Branch and a Records Branch in 1954. The secretariat transferred the

Document Security Branch to the Oce of the Air Adjutant General in

late 1953 or early 1954.

33

The secretariat had formally established the Special Projects Oce

in April 1949 under the Oce of the Special Military Assistant. Its initial

assignments were to prepare the annual report of the Oce of the Secretary

of the Air Force and provide research for the secretary. In February 1952,

Secretary Finkletter moved the Special Projects Oce to the Oce of

the Administrative Assistant. By 1955, Special Projects had become the

Research and Analysis Division.

34

At some point between 1952 and 1953, the secretariat moved the Air

Force Board for Correction of Military Records from the Oce of the

Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Management) to the Oce of the

30. OSAF history, 1950–51, 30.

31. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directories, 1952–54.

32. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directories, 1951–53.

33. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directories, 1952–54; Department of

Defense Telephone Directory, April 1955, C–61.

34. John J. McLaughlin, Oce Memorandum 20-11, April 21, 1949, AF/HOH; McLaughlin, Oce

Memorandum 20-11, Supplement 1, February 20, 1952, AF/HOH; Secretary of the Air Force Key

Personnel Telephone Directories, 1950–54; Department of Defense Telephone Directory, April 1955, C–61.

11

Administrative Assistant. Whether this reassignment took place by order

of the new secretary of the Air Force, Harold E. Talbott, is unclear. Most

of the reorganization within the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

had already taken place before the inauguration of President Dwight

Eisenhower in January 1953. Talbott and his new under secretary and

assistant secretaries took oce in February.

35

The secretariat transferred the Air Force Printing Committee from

the Office of the Assistant Secretary (Materiel) to the Office of the

Administrative Assistant in February 1952. This department became

known as the Air Force Committee for the Improvement of Paperwork in

1955 but was back as the Printing Committee by 1959.

36

A new entity the secretariat placed under the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant in 1953 was the Air Force Civilian Attorney Qualifying Com-

mittee, which the Air Force had created a year earlier. This board of

civilian attorneys, appointed by the secretary of the Air Force, continues to

the present and approves the appointments, promotions, and assignments

of personnel in civilian attorney positions across the service. It remained

under the Oce of the Administrative Assistant for fteen years.

37

By 1952–53, the Oce of the Administrative Assistant had evolved

into the structure it would have for a quarter century. By 1955, the three

divisions had the names they would carry forward: Administrative Services,

Correspondence Control, and Research and Analysis. Names of the divisions

changed in the 1960s and 1970s, and branches under them came and went, but

the oce operated with three divisions quite similar to these that McLaughlin

constituted until the divisional structure began to dissolve in the late 1970s.

The Special Projects Oce was already gaining notice in expanding

circles by the time Secretary Finletter transferred it to the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant in 1952. The “special projects” started in early

1948 with one colonel who provided research for the secretary for speeches

and congressional testimony and wrote the rst yearly report for the Oce

35. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directories, 1950–53. The history Zubko

drafted in 1957 gave details on when the secretariat founded the board but did not note when it

came under the auspices of the Oce of the Administrative Assistant. Assistant Secretary Zuckert

established the board on November 30, 1948. On February 24, 1949, Secretary Symington conferred

the powers of the board to Zuckert that Transfer Order No. 23 had given Symington. This order had

transferred the function of correction of military records related to airmen from the Army to the Air

Force. OSAF history, 1957, 51–53.

36. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directories, 1952–54; Department of

Defense Telephone Directories, 1955–59.

37. Secretary of the Air Force Key Personnel Telephone Directory, July 20, 1953, 8; OSAF history,

1957, 53–54; Air Force Instruction 51-107, “Employment of Civilian Attorneys,” October 24, 2011, 7,

http://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a3_5/publication/a51-107/a_51-107.pdf. Prior to

the establishment of this committee, a joint committee with members from the Army and the Air Force

had carried out these functions. OSAF history, 1957, 53.

12

of the Secretary. A second colonel joined the operation in the fall of 1948,

and the secretariat formalized the Special Projects Oce in April 1949

under the Oce of the Executive Assistant. The oce began keeping les

on key national defense subjects and personalities and initiated a small

clippings service for Secretary Symington, an operation that blossomed

when the ocers hired a civilian, Harry Zubko, in 1950 to take over the

duties. Zubko reviewed newspaper coverage each morning of Air Force-

and national security-related matters and briefed Secretary Finletter. He

expanded the clippings le with an edition for General Vandenberg as

well. Soon, the other members of the Joint Chiefs and the secretary of

defense wanted copies, and Finletter assigned Zubko a couple of enlisted

airmen to help with the expanding task. One was MSgt. Amabel Earley,

who became the namesake of the “Early Bird” morning edition. Within a

few years, their Current News, initially a mimeographed newsletter, was

going all over the Pentagon and beyond, reaching a circulation of 20,000

by the time Zubko retired in 1986. For many years, Zubko also wrote

the annual report for the Air Force.

38

Even as McLaughlin was reorganizing the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant in the early 1950s to meet the evolving needs of the secretariat, he

feared that expansion of the Oce of the Secretary was getting out of hand

and creating a heavier workload for many, including his sta. McLaughlin

put his concerns into a memorandum for Assistant Secretary Zuckert in

January 1952. One issue was the growing number of deputies within the

secretariat. At that time, Zuckert had six, the other assistant secretary had

two, and a special assistant had two. According to McLaughlin, the deputy

positions decentralized operations that could be handled more eciently

through his office, caused problems with communications, created

overlapping responsibilities, and risked the rise of small administrative

empires within the secretariat.

39

There was a fair amount of turnover in the Oce of the Secretary of

the Air Force during the 1950s as Donald A. Quarles, James H. Douglas Jr.,

and Dudley C. Sharp followed Finletter and Talbott in relatively short terms

as secretary. There was also restructuring across the Pentagon with the

Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 and its implementation

in 1959. These developments had little immediate impact on the Oce of

38. John J. McLaughlin, Oce Memorandum 20-11, April 21, 1949, AF/HOH; McLaughlin,

“Special Projects Oce,” memorandum, July 27, 1951, AF/HOH; Harry M. Zubko, “Historical

Notes Highlight Pentagon Players—Parts 1–3,” Foresights and Hindsights from Harry, http://

foresightsandhindsights.blogspot.com/2017/06/; Richard Scheinin, “Harry Zubkoff and His

Pentagon Papers,” Washington Journalism Review, March 1985, 34–35, https://www.cia.gov/library/

readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90-00845R000100200001-4.pdf.

39. Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 167.

13

the Administrative Assistant, however, which kept the same structure and

primary functions outlined above through the rest of the decade.

40

McLaughlin had anticipated further Defense reorganization under

President Eisenhower and had lobbied as early as May 1953 for a study

of the responsibilities of the secretariat and the Air Sta. Many in the

secretariat had complained for years about what Air Force historian George

M. Watson Jr. called “the lack of clear authority lines.” Watson noted that

“growing confusion frustrated workings between the OSAF [Oce of the

Secretary of the Air Force] and the Air Sta and had damaging eects on

specic areas such as procurement.” It took three years after McLaughlin’s

rst suggestion, however, until Secretary Quarles approved such a study.

41

McLaughlin and his sta completed “The Secretary of the Air Force-

Air Staff Relationship Study” in October 1956. It found significant

disagreement about roles and responsibilities of the secretariat and the Air

Sta, even within each oce. Secretary Quarles formed a study group to

follow up on the survey, but it had little success nding common ground.

As Watson observed, the 1956 study had “identied a disease, but not a

cure. However, by airing complaints, it allowed many oces within both

the OSAF and the Air Sta the opportunity to recognize that they shared

similar problems.” The root of many of them was the increasing power

and reach of the Oce of the Secretary of Defense, an issue exacerbated

by the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 but not of full-

measure impact until the 1960s.

42

The election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 brought a founding

executive back to the secretariat: Eugene Zuckert, who took office as

Kennedy’s secretary of the Air Force in January 1961. Faced with not

only the growing power of the Department of Defense but also with a

strong and often inexible secretary of defense in Robert S. McNamara,

Zuckert longed for a return to the days when more authority had rested

in the hands of the service secretaries, as had existed when he worked

for Secretary Symington. Zuckert had McLaughlin and his sta draft an

article for Air University Quarterly Review that outlined a “revolution

in management” of the Air Force that pointed back to the earlier model.

40. For an account of the functions of the Oce of the Administrative Assistant as for 1957, see

OSAF history, 1957, 47–54. As for the impact of the legislation, George Watson wrote that “the OSAF

under Secretaries Douglas and Sharp did not appear to be radically aected by the 1958 Defense

Reorganization Act. The Air Secretary’s power was dwindling to be sure, but there was no tyrannical

hand within the OSD [Oce of the Secretary of Defense] making life any more uncomfortable than it

had been for Secretary Quarles. The nal evaluation and implementation of the two reorganization acts

of the 1950s would be left to the next administration’s Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara.”

Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 202–3.

41. Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 167–68.

42. Ibid., 168–74 (quote, 174).

14

The draft of the article bore Zuckert’s name, but it appeared in print in

1962 under McLaughlin’s.

43

All was not well between the former colleagues, however, and

disagreements boiled over in 1963. According to Zuckert, McLaughlin

was “doing all sorts of crazy things,” which the secretary attributed to the

administrative assistant becoming “mentally disturbed, or an alcoholic, or

both.” McLaughlin made a threat on Zuckert’s life, one Zuckert took so

seriously that he had security guard his house that night. Zuckert conceded

that “I stuck with him too long,” but after this incident, McLaughlin had to

go. In October 1963, the Air Force lost the only administrative assistant in

its sixteen-year history. McLaughlin’s deputy, Joseph P. Hochreiter, served

as acting administrative assistant until February 1964.

44

Despite the unfortunate end to McLaughlin’s career, his inuence on

the Office of the Administrative Assistant was profound. He launched

and cultivated it, and the structure he developed for it in the early 1950s

remained in place long after he left civilian service with the Air Force.

Secretary Zuckert lled the administrative assistant position from the

Air Sta, naming John A. Lang Jr., who had been the deputy for Reserve

and ROTC aairs, to replace McLaughlin. Lang was a North Carolina

native, born in 1910. He had enlisted in the Army Air Forces as a private

in 1942 and was a major when he left active duty in 1946. Lang accepted a

commission in the Air Force Reserve and rose to the rank of major general.

Before he joined the Air Sta in 1961, he had served on stas of several

U.S. congressmen between 1947 and 1961.

45

According to Zuckert, “everyone liked” Lang, who “represented

a calming inuence after McLaughlin.” Lang “had a lot of energy, and

people would work for and with him.” Zuckert said that he called Lang

“Magnolia Blossom” because of his “southern accent and that line of

bullshit he handed out.” He described Lang as “a good soldier” and also

as someone who “loved the Air Force; the Air Force was his passion.”

46

43. McLaughlin, “Organization of the Air Force,” 3. The draft listing Zuckert as the author is in the

les at AF/HOH. Whether Zuckert shifted authorship credit in appreciation of McLaughlin’s eort or

in an attempt to avoid direct responsibility for it in McNamara’s eyes is unknown. For McNamara’s

impact on the secretariat, see Watson, Oce of the Secretary of the Air Force, 205–44; for Zuckert’s

frustrations about the limited power of the service secretaries by the time he was in oce, see Zuckert

interview, 3–19.

44. Zuckert interview, 32. McLaughlin’s obituary stated that he retired from his position

with the Air Force, although he was only forty-four years old at the time. McLaughlin died tragically

in 1972 from injuries sustained when he was hit and pinned by his own car while trying to stop it

from rolling out of his driveway. “John J. McLaughlin Dies.” According to Zubko, Zuckert red

McLaughlin. Elaine Blackman, “Harry’s Wrap of ’50s Pentagon Memories—Part 4,” Foresights and

Hindsights from Harry, June 29, 2017, http://foresightsandhindsights.blogspot.com/2017/06/harrys-

wrap-of-50s-pentagon-memories.html.

45. Lang ocial Air Force biography, AF/HOH.

46. Zuckert interview, 39.

15

The Research and Analysis Division of the Oce of the Administrative

Assistant grew during the 1960s, to a sta of twenty-eight by 1968.

A series of Air Force ocers continued to serve as division director,

as they had since the section’s inception. Harry Zubko recalled that

“every one of them was a sharp, intelligent, top-notch guy,” as all had

been hand-picked for the prestigious assignment of directly supporting

the secretary of the Air Force. The best known of these ocers was Col.

John L. Frisbee, who became editor of Air Force Magazine after he

retired from the service. Murray Green, the long-time civilian deputy

director, and Zubko provided continuity for the sta. In addition to

the Current News service, which expanded in the 1960s (see below),

the division’s primary focus remained writing and research support

for the secretariat, including the preparation of speeches and special

reports for the secretary of the Air Force, as well as the annual posture

statements for Congress. Green tracked public reaction to defense-

related issues, including the Vietnam War, for Zuckert’s successor,

Secretary Harold Brown.

47

The Research Branch of the Research and Analysis Division had its

tasks expanded in 1963 when Secretary McNamara designated the Air

Force as executive agent for the Department of Defense for dissemination

of military-related news stories. Prior to that time, the Joint Chiefs, the

Oce of the Secretary of Defense, and each service secretariat had its own

clippings service. McLaughlin had suggested consolidation of Pentagon

news gathering under the Air Force as early as 1953, but it took a decade

before anyone acted on the idea. With McNamara’s designation, Current

News and the “Early Bird” edition circulated more widely in the Pentagon

and to other government agencies, extending the responsibilities of branch

head Zubko and his small sta.

48

47. File of correspondence concerning the presentation of the Legion of Merit to Lt. Col. Larry J.

Larsen, IRIS no. 01097707, Air Force Historical Research Agency (AF/HRA), Maxwell Air Force

Base, AL; Blackman, “Harry’s Wrap of ’50s Pentagon Memories—Part 4” (quote); “John Frisbee dies

at 83,” Washington Post, August 31, 2000; “Murray Green, 86, Analyst, Historian for the Air Force,”

Baltimore Sun, October 26, 2002.

48. John J. McLaughlin, memorandum for Under Secretary James H. Douglas Jr., April 1, 1953, AF/

HOH; James H. Douglas Jr., memorandum for John J. McLaughlin, April 2, 1953, AF/HOH; Elaine

Blackman, “Dad’s Advice on Reading and Speeding it Up (and Why JFK Called Him on It),” June 20,

2015, Foresights and Hindsights from Harry, http://foresightsandhindsights.blogspot.com/2015/06/

dads-advice-on-reading-and-speeding-it.html; Scheinin, “Zubko and His Pentagon Papers,” 35.

The oce had authority as executive agent for national security news analysis under Department

of Defense Directive 5160.52. According to those who knew both men, there was a long-standing

professional rivalry between Murray Green and Zubko. The Scheinin article has Green taking credit

for overseeing Current News until his retirement in 1970, which he technically did as deputy director

of the division, but by all accounts, Zubko ran the operation from its inception. Several articles

support this point; see for example “A Pentagon Newspaper Consisting of Clippings,” New York

Times, July 6, 1983.

16

Secretary McNamara brought Zubko and his clippings service to the

attention of senior ocials at the White House, particularly McGeorge

Bundy, the special assistant for national security aairs, and Pierre E.

Salinger, the president’s press secretary. Salinger called Zubko regularly

to ask him to look for various items in the publications he reviewed, and

Zubko began sending Salinger several dozen articles a day for the press

secretary to share with President Kennedy. One day Salinger phoned

Zubko and put Kennedy on the line. “These articles you send me, do you

read them all yourself?” the president asked. When Zubko said that he

did, Kennedy asked him how fast he read, stating that he had a hard time

keeping up with all the news clippings in addition to everything else he

had to review. Zubko asked the president if he wanted him to cut back on

the number of articles he was sending. “No, no,” Kennedy replied, “I just

want to be sure that you suer as much as I do. Keep it coming.”

49

The increased visibility brought more assignments. Zubko said that many

times across his career, senior staers asked for his oce to prepare position

papers for secretaries of defense and even presidents, and on occasion he drafted

national security sections of presidential speeches. After the assassinations of

Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, President Lyndon B.

Johnson formed the U.S. National Commission on the Causes and Prevention

of Violence, chaired by Milton S. Eisenhower. According Zubko, his oce

was “deeply involved” in the commission’s study.

50

In the 1960s, the secretariat also became engaged in a project that

had a much lower public prole; in fact, the federal government did not

acknowledge the existence of the National Reconnaissance Oce (NRO)

until 1992.

51

President Eisenhower approved formation of the NRO in

August 1960 to coordinate Air Force and Central Intelligence Agency

space reconnaissance efforts. Joseph V. Charyk, the under secretary

of the Air Force, became dual-hatted as the rst director of the NRO,

reporting directly to Secretary of Defense Thomas S. Gates Jr. on NRO

matters.

52

When the Kennedy administration came into oce in January

1961, McNamara informed Zuckert that Charyk would remain the under

secretary. As Zuckert put it, Charyk was “cognizant of a lot of things

which McNamara felt would be very hard to transfer to someone else,

49. Blackman, “Dad’s Advice on Reading and Speeding it Up.”

50. Elaine Blackman, “Letter to Professors Shed More Light on Harry’s Life,” September 8, 2016,

Foresights and Hindsights from Harry, http://foresightsandhindsights.blogspot.com/2016/09/letters-

to-professors-shed-more-light.html.

51. “Out of the Black: The Declassication of the NRO,” National Security Archive, September 18,

2008, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB257/index.htm.

52. Robert L. Perry, Management of the National Reconnaissance Program, 1960–1965 (1969;

repr., Washington, DC: National Reconnaissance Oce, 1999), 13–15.

17

such as the ‘black programs.’”

53

With the exception of just a couple of

periods, the under secretaries of the Air Force remained the directors of

the NRO through 1986.

54

The Oce of the Administrative Assistant became the conduit for Air

Force involvement with the NRO. Air Force personnel, both military and

civilian, who worked in the “black world,” as it came to be known, were

ocially assigned to the Oce of the Administrative Assistant. As William

A. Davidson Jr., who became the administrative assistant in 1994, later put

it, “The original part of [SAF/AA] working ‘black programs’ starts with the

NRO relationship, and trying to act as the cover mechanism for that so they

could legitimize all the activities that would occur.” According to Davidson,

“They used to call it the ‘Green Door,’ which was special assignments

anywhere; it covered assignments if we didn’t want someone to know who

the people were. If you were out on cover with some other agency, you’d

get assigned through that process, and they’d ensure you were taken care

of.” The military assistant in the Oce of the Administrative Assistant and

his executive ocer coordinated much of this activity.

55

As the oce’s portfolio expanded, Lang undertook some minor

reorganization of the Oce of the Administrative Assistant in 1965–66

that had more to do with streamlining than with extensive changes of

function. Administrative Support became the Management Division, while

Correspondence Control transitioned to become the Executive Support

Division. Research and Analysis remained as it was, printing moved under

Executive Support, and the Air Force Board for Correction of Military

Records and the Air Force Civilian Attorney Qualifying Committee

remained separate offices that reported directly to Lang. In 1968, the

secretariat placed the Board for Correction of Military Records under

the Oce of the Assistant Secretary (Manpower and Reserve Aairs)

and made the Civilian Attorney Qualifying Committee a separate entity,

associated with other committees and boards.

56

The Department of the Air Force publication of “Organizations

and Functions” (Chartbook) as of December 1969 stated that the Oce

of the Administrative Assistant was “responsible for management and

administration” of the Oce of the Secretary. The rst of several specic

duties listed was administering contingency funds, followed by “developing

53. Zuckert interview, 19.

54. Charyk, Brockway McMillan, John L. McLucas, James W. Plummer, Hans M. Mark, and Edward C.

“Pete” Aldridge Jr. all served concurrently as under secretary and director of the NRO. “NRO Directors,”

National Reconnaissance Oce, http://www.nro.gov/history/csnr/leaders/directors/index.html.

55. William A. Davidson Jr., interview with Priscilla D. Jones and Kenneth H. Williams, February

26, 2018, AF/HOH (hereafter Davidson interview).

56. Department of Defense Telephone Directories, 1966–68.

18

and maintaining the continuity of the operations plan” for the secretariat.

The next item the Chartbook highlighted was the Defense-wide clippings

and news service, which continued to have the formal agency McNamara

had given it, under the guidance of the Oce of the Assistant Secretary

of Defense (Public Aairs). Other duties included control of the Air

Force order system; coordinating Air Force responses to questions from

the White House and the Oce of the Secretary of Defense; reviewing

“miscellaneous claims against the Air Force,” including those under the

Military Claims Act, and announcing the decisions for the secretary; and

custody and control of the Air Force Seal, which the oce had maintained

since 1947. After Congress passed the Freedom of Information Act in 1967,

the secretariat placed the Oce of the Administrative Assistant in charge

of reviewing FOIA requests involving the Air Force and announcing the

decisions of the secretary.

57

Thomas W. Nelson joined the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

around the time of the reorganization in 1966 as chief of the newly constituted

Management Division. He became the acting deputy administrative

assistant in 1969, the permanent deputy in 1970, and followed Lang as

the administrative assistant when Lang retired in 1971. Nelson had been

born in Idaho in 1921, received the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart while

serving in the Army as an enlisted man during World War II, and had begun

working as a civilian in personnel for the Air Force in 1948.

58

Nelson oversaw more reorganization in the rst part of the 1970s as the

Executive Support Division became the Administrative Systems Division.

The Oce of the Administrative Assistant also opened what it labeled the

Executive Agency Service department, with Zubko dual-hatted as the

head of this area as well as Research and Analysis. The latter division by

this stage was fully focused on news gathering and dissemination, while the

military-staed component that previously had been under Research and

Analysis moved to the Executive Agency Service as the Policy Analysis

Group. This section continued to write speeches and presentations for the

secretary, as well as reports for Congress. Zubko himself was a point

person for both the news and the research sides of the operation. People

from the secretariat, the Air Sta, and other areas of the Pentagon came to

him when someone needed information on a subject quickly. Zubko had

the les, institutional memory, and connections to get questions answered.

59

57. Chartbook, December 31, 1969, 12 (dated August 1968); “Oce of the Secretary of the Air

Force,” Air Force Fact Sheet 75–18, October 1975, 7–8.

58. Nelson ocial Air Force biography, AF/HOH. Upon his retirement, Lang took a senior admin-

istrative position at East Carolina University. Zuckert interview, 39.

59. Department of Defense Telephone Directories, 1971–75; Davidson interview. Henry A.

Kissinger, who had served with Zubko in a U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps unit during World

War II, got Zubko to let his researchers use Zubko’s les as they helped Kissinger prepare the

volumes of his memoirs. Scheinin, “Zubko and His Pentagon Papers,” 34.

19

During this period, the secretariat was “pretty casual,” according to

William Davidson, and the Office of the Administrative Assistant was

“fairly laid back.” The secretariat as a whole was only around 320 people.

Unlike during the 1950s when there was overlap and confusion about

roles between the secretariat and the Air Sta, by the 1970s, “the two

stas operated totally independently,” Davidson recalled. “It was literally

completely divided, except at the very top.”

60

When Nelson retired in January 1980, his deputy, Robert W.

Crittenden, became the acting administrative assistant. At some point

around this transition period, Antonia Handler Chayes, the under secretary

of the Air Force, led an internal study that concluded that the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant should be abolished, with its functions parceled

across the secretariat. Secretary Hans M. Mark disagreed with Chayes’s

nding but understood that he would have to bring in someone from the

outside to institute reforms.

61

Mark had known Robert L. McCormick since McCormick had been the

executive ocer for the assistant secretary for research and development

in the early 1970s. When McCormick, an Iowa native who rose to the rank

of colonel in the Air Force, retired from active duty in 1975, Mark had

helped him get hired in a senior administrative position with the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration, where Mark worked at the time as

director of NASA’s Ames Research Center. In August 1980, Mark brought

McCormick to the secretariat as the new administrative assistant.

62

Davidson, who came to the Oce of the Administrative Assistant

in 1983 as a military executive ocer, described McCormick as “pretty

intense and very organized,” a change for a sta used to a slower pace

under Nelson. McCormick transferred Crittenden and brought in new

people to oversee several areas, including personnel and the mess.

“Those types of things got changed,” Davidson recalled, “not necessarily

organizational structures,” as McCormick sought to make the operation

“more professional.”

63

There was room for organizational innovation because the divisional

architecture that John McLaughlin had developed for the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant three decades earlier was breaking down by the

time McCormick took oce. Most of the authority had shifted from the

divisional level to various branches, several of which had become little

efdoms. The oce continued to perform the same functions, but by 1982,

the formal structure under three divisions was gone. When McCormick

60. Davidson interview.

61. Ibid.

62. Ibid.; McCormick ocial Air Force biography, AF/HOH.

63. Davidson interview. Al C. Sisneros, who McCormick hired, ran what became the executive

dining facility for nearly thirty years.

20

oversaw reorganization in 1987 as the Air Force began implementing

the Goldwater-Nichols Act, the new hierarchy for the Office of the

Administrative Assistant was built around branches, not divisions.

64

In terms of personnel, the largest of the efdoms was what had become

known as the News Clipping and Analysis Service. McCormick and

Zubko already knew each other from McCormick’s tour in the secretariat

in the early 1970s and became “very close,” according to Davidson.

McCormick encouraged expansion of the oce’s publications and of

their dissemination. Zubko also had a direct relationship with Caspar

Weinberger, who became secretary of defense in 1981. Like nearly all the

senior leaders during the period, Weinberger awaited delivery of the news

summary every morning. “We used to call it ‘management by the Early

Bird,’” Davidson recalled, as the senior executives read the newsletter

while on the way to the oce “so they knew what their work was going to

be,” what issues were the most pressing.

65

In fact, embarrassing stories about activities of another service

prompted what became the most signicant change in the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant during this period. An Army secret operation in

the early 1980s known as Yellow Fruit, which supported the Contras in

Nicaragua and included some of the early money-laundering activities

related to those of the Iran-Contra scandal, had been the subject of an

internal Pentagon investigation for two years when news of Yellow Fruit

reached the press in 1985.

66

With the Air Force determined to avoid

similar irregularities and scandal with its “black programs,” the under

secretary, Edward C. “Pete” Aldridge Jr., who was also director of the

NRO, asked Davidson to undertake “a study and build an oversight

mechanism that would ensure that the Air Force wouldn’t run into those

kinds of problems.” Davidson’s background was with the Oce of Special

Investigations, and he had been detailed to the NRO in the 1970s as its

chief of polygraph, so he had a good understanding of its organization

and security apparatus. Davidson was due to rotate out of the Oce of the

Administrative Assistant to another military assignment, but Aldridge told

64. Department of Defense Telephone Directories, 1980–87; Davidson interview.

65. Davidson interview (quotes); McCormick nomination for Federal Executive of the Year, 1984,

courtesy of William A. Davidson Jr.; James Burton, The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old

Guard (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), 95–96; Scheinin, “Zubko and His Pentagon

Papers,” 33.

66. Caryle Murphy and Charles R. Babcock, “Army’s Covert Role Scrutinized,” Washington

Post, November 29, 1985; Je Gerth, “Pentagon Linking Secret Army Unit to Contra Money,” New

York Times, April 22, 1987; Michael Smith, Killer Elite: The Inside Story of America’s Most Secret

Special Operations Team (New York: St. Martin’s, 2006), 110–17; William M. LeoGrande, Our Own

Backyard: The United States in Central America, 1977–1992 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North

Carolina Press, 1998), 385–87.

21

him that he would be staying and standing up the new program. Newly

promoted Colonel Davidson became head of the Department for Security

and Investigative Programs (SAF/AAZ). Upon retirement from the service

in 1990, Davidson became the deputy administrative assistant, and he

succeeded McCormick as administrative assistant in 1994.

67

As Air Force involvement in classified programs grew, so did the

complexity of tracking the funding for them. The Oce of the Administrative

Assistant had been in charge of the service’s contingency funds since the

founding of the Air Force, but McCormick instituted expanded controls

and ordered regular audits. His system of safeguards became a model for

other areas of the Air Force and across the Department of Defense.

68

From its interim status in 1947 through the rst four decades of the Air

Force, the Oce of the Administrative Assistant emerged as an integral part

of the operation of the service. Its greatest power came to rest in its control

of contingency funds, but its inuence through the array of services that

came under its auspices grew wider as years passed, even more so as the

“black programs” expanded. The oce’s most widely known operation,

the news and clippings service, continued for several years after Zubko’s

retirement in 1986 but eventually transitioned to the public aairs oce of

the Department of Defense and has since ceased.

67. Davidson interview (quote); Davidson ocial Air Force biography, AF/HOH.

68. McCormick nomination for Federal Executive of the Year, 1984.

23

The Administrative Assistant to the

Secretary of the Air Force:

Goldwater-Nichols and Beyond

Priscilla D. Jones

Part two

introduction

Since the establishment of the U.S. Air Force in September 1947, the

administrative assistant to the secretary of the Air Force (SAF/AA) has

represented departmental continuity and institutional memory. By March

2018, eight men and one woman had been sworn in as administrative

assistants and/or as acting administrative assistants. The tenures of the

three longest-serving administrative assistants, William A. Davidson, John

J. McLaughlin, and Robert J. McCormick, totaled forty-seven years of the

service’s seventy-one-year history.

1

Several recurring themes run through the history of SAF/AA. One, as

mentioned, is continuity, from one Air Force secretary to another; from

one Air Force chief of staff to another; from one president to another.

From August 1980 through March 2018, the tenures of four administrative

assistants—McCormick, Davidson, Timothy A. Beyland, and Patricia J.

Zarodkiewicz—intersected those of twenty-two secretaries and/or acting

secretaries of the Air Force; thirteen chiefs of sta or acting chiefs of sta;

and seven presidents. In Davidson’s view, the “number one job” of the

administrative assistant is to be “the long-term . . . advisor” to each Air

Force secretary; “the rest of it is secondary.”

2

Another recurring theme is an aspect of an Air Force-wide issue: how

can the business of the department be done more eectively? How can

The author thanks colleagues Yvonne A. Kinkaid, Helen T. Kiss, Randy E. Richardson, Jean A. Mansavage,

Kenneth H. Williams, and William C. Heimdahl (AF/HO retired) for their contributions to this study.

1. Davidson served as acting SAF/AA from Apr 1–Jun 14, 1994 and as SAF/AA from Jun 15,

1994–Sep 30, 2011 (though he returned, until his ocial Nov 1 retirement date). McLaughlin served

as SAF/AA from Sep 27, 1947–Oct 4, 1963. McCormick served as SAF/AA from Aug 25, 1980–

Mar 31, 1994). Headquarters United States Air Force Key Personnel, updated by Maj Laura E.

Cox (Washington, DC: Air Force Historical Studies Oce, Jan 2013), p 14. [https://media.defense.

gov/2013/Apr/10/2001329974/-1/-1/0/AFD-130410-035.pdf, accessed Jan 29, 2018.] According to

the 1980 Statistical Digest, McCormick’s tenure began on Aug 24, 1980.

2. Intvw, C. R. Anderegg, Air Force History and Museums Program director, with William A.

Davidson, SAF/AA, Jul 15, Aug 19, and Sep 16, 2011, at the Pentagon.

24

duplication be avoided and integration and coordination be enhanced?

These tasks have a larger context also: how can the services and other

government agencies work more eectively together?

This leads to a third recurring theme: the ability of the Air Force in

general, and SAF/AA in particular, to work with outside agencies on highly

classied projects. As retired administrative assistant Davidson recalled in

a February 2018 interview, what SAF/AA “was really equipped to do was

to handle the black world.” This was due, in significant part, to his own

professional background and experiences and those of other individuals

who worked there. And the outside agency with which the secretary of

the Air Force and SAF/AA had perhaps the closest connection, since at

least the late 1970s, was the National Reconnaissance Oce (NRO).

3

Air

Force secretaries Dr. Hans M. Mark and Edward C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr.,

exemplify this connection. Mark was NRO director from August 1977

until October 1979; acting Air Force secretary from May until July 1979;

and Air Force secretary from July 1979 until February 1981. Aldridge was

NRO director from August 1981 until December 1988; acting Air Force

secretary from April until June 1986; and Air Force secretary from June

1986 until December 1988.

4

These three themes are key also to understanding why certain activities

are placed in, or removed from, the SAF/AA portfolio. The rst reason:

continuity. The mission and responsibilities of the administrative assistant

to the Secretary of the Air Force are not tied to any particular administration;

they are tied to process, ongoing and independent of politics and changes in

senior leadership. Second: better ways to do business. As Davidson recalled,

SAF/AA has “a history of taking something, and trying to make it better,

and giving it to somebody else.” And here, the involvement of various Air

Force secretaries and chiefs, vice chiefs, and assistant vice chiefs of sta, in

directing organizational changes in several cases, should not be overlooked.

Third: “it’s not just Air Force.” That is, Davidson noted, SAF/AA becomes

involved when other agencies are involved in a particular activity or task,

working together with the Air Force. That, he said, was “the old lineage of

the NRO. It goes back to the way that the Air Force knows how to deal with

multiple agencies. And we never get credit for it.”

Funding and, consequently, personnel levels are a fourth reason

functions are renamed or moved in and out of SAF/AA. Davidson

3. Unless otherwise indicated, all Davidson quotes are from Intvw, Priscilla D. Jones, Air Force

Historical Support Division (AF/HOH) chief, histories and studies, with Col William A. Davidson,

USAF (Ret), retired SAF/AA, Feb 26, 2018, at the AF/HOH, Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, DC.

4. Cox, HQ USAF Key Personnel, p 4. NRO, list of NRO Directors. [https://www.nro.gov/History-

and-Studies/Center-for-the-Study-of-National-Reconnaissance/NRO-Directors/, accessed Mar 18, 2019.]

25

recalled that even before the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense

Reorganization Act of 1986, the Air Force labored under manning re-

strictions. The Secretariat was permitted 320 personnel, and the Air Sta

had a separate staffing number. The black world did not, officially,

exist and so had its own, classied number. The Goldwater-Nichols Act

combined the Secretariat and the Air Sta numbers and directed that, as

of October 1, 1988, the total number of permanent-duty military members

and civilians could not exceed 2,639.

5

After that, he said, “people start[ed]

maneuvering” and wondering how best to accomplish the mission, which

was not getting smaller, with fewer sta. Field operating agencies (FOAs)

and special oces, whose personnel were not included in the Headquarters

manpower numbers, were put into place “in order to get the job done.”

Air Force-wide activities such as the Air Force Central Adjudication

Facility (AFCAF), the Air Force Declassication Oce (AFDO), and the

Air Force Art Program Oce (AFAPO) were not counted, although they

belonged to the administrative assistant to the Air Force secretary. So as

SAF/AA was “dropping people out, moving people here, doing dierent

things” to accomplish the mission, the nature of the organization began,

and continued, to change:

. . . what eventually happens is, it forces you to combine [func-

tions. This is] sometimes good, sometimes bad. And then it

forces you to get out of support business. . . . It tends to force

you into contractors, which tends to be more expensive, once the

contractors realize you no longer have the capability to do this.

The history of SAF/AA is not easy to analyze or even to describe.

Few documentary sources—such as the June 2007 memorandum about

the establishment of the information management directorate (HAF/IM)

and its information chart Mr. Davidson shared with me, and the HAF2002

report he hoped still existed in SAF/AA files—are presently available

that would explain why certain functions came in and out of the oce.

Even tracing the basic evolution of the three-letter subordinate oces

is problematic due to conicting and/or incomplete organization charts

and personnel directories. For example, the important Headquarters Air