1

ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY –

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS,

CRYPTOCURRENCY, NON-FUNGIBLE TOKENS,

AND THE METAVERSE

Gerry W. Beyer

*

and Kerri Nipp

**

I. I

NTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 6

II. T

YPES OF DIGITAL ASSETS .................................................................. 6

A. Personal ..................................................................................... 7

B. Social Media .............................................................................. 7

C. Financial Accounts .................................................................... 8

D. Business Accounts ..................................................................... 8

E. Domain Names or Blogs ............................................................ 8

F. Loyalty Program Benefits .......................................................... 9

III. I

MPORTANCE OF PLANNING FOR DIGITAL ASSETS .............................. 9

A. To Make Things Easier on Executors and Family Members ..... 9

B. To Prevent Identity Theft ......................................................... 10

C. To Prevent Financial Losses to the Estate .............................. 11

1. Bill Payment and Online Sales.......................................... 11

2. Domain Names .................................................................. 11

3. Encrypted Files ................................................................. 13

4. Virtual Property ................................................................ 13

D. To Avoid Losing the Deceased’s Personal Story ..................... 13

E. To Prevent Unwanted Secrets from Being Discovered ........... 14

F. To Prepare for an Increasingly Information-Drenched

Culture ..................................................................................... 14

IV. O

BSTACLES TO PLANNING FOR DIGITAL ASSETS .............................. 15

A. User Agreements ..................................................................... 15

1. Terms of Service Agreements ............................................ 15

2. Ownership ......................................................................... 16

B. Federal Law ............................................................................ 16

1. Stored Communications Act .............................................. 16

a. In re Facebook, Inc. (Daftary Case) ........................... 17

b. Ajemian v. Yahoo! ..................................................... 17

2. Computer Fraud and Abuse Act ........................................ 18

3. Interface with User Agreements ........................................ 18

C. Safety Concerns ....................................................................... 19

D. Hassle ...................................................................................... 20

* Governor Preston E. Smith Regents Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law

** Principal, Fiduciary Counsel, Bessemer Trust

2 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

E. Uncertain Reliability of Online Afterlife Management

Companies ............................................................................... 20

F. Overstatement of the Abilities of Online Afterlife

Management Companies ......................................................... 20

V. B

RIEF HISTORY OF FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGITAL ASSETS ........... 21

A. Early State Law ....................................................................... 21

1. First Generation ................................................................ 21

2. Second Generation ............................................................ 22

3. Third Generation .............................................................. 22

B. First Attempt at a Uniform Act ................................................ 23

C. Privacy Expectation Afterlife and Choices Act ....................... 24

VI. R

EVISED UNIFORM FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGITAL ASSETS ACT ... 25

A. Definitions ............................................................................... 26

1. Catalogue of Electronic Communication .......................... 26

2. Content of an Electronic Communication ......................... 26

3. Digital Asset ...................................................................... 27

4. Online Tool ....................................................................... 27

B. Applicability ............................................................................ 29

C. Priority of Instructions ............................................................ 29

D. Disclosure Procedures ............................................................ 30

1. Personal Representatives of Estates ................................. 30

a. Contents ...................................................................... 30

b. Catalogue and Other Digital Assets ........................... 31

c. Practical Problems ..................................................... 31

d. Advice ......................................................................... 32

2. Agents Under Powers of Attorney ..................................... 33

a. Contents ...................................................................... 33

b. Catalogue and Other Digital Assets ........................... 33

3. Trustees ............................................................................. 33

a. Trustee Is Original User ............................................. 33

b. Trustee Is Not Original User ...................................... 34

4. Guardians (Conservators) ................................................ 34

E. Custodian’s Response to Request to Disclose Digital

Assets ....................................................................................... 35

1. Timing ............................................................................... 35

2. Notice to User of Request ................................................. 35

3. Method of Custodian’s Disclosure .................................... 35

4. Failure to Disclose ............................................................ 36

5. Custodian Protection ........................................................ 36

F. Duty and Authority .................................................................. 37

VII. P

LANNING SUGGESTIONS .................................................................. 37

A. Take Advantage of Online Tools ............................................. 38

B. Back-Up to Tangible Media .................................................... 38

C. Prepare Comprehensive Inventory of Digital Estate .............. 39

1. Creation ............................................................................ 39

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 3

2. Storage .............................................................................. 39

D. Provide Immediate Access to Digital Assets ........................... 40

E. Authorize Agent to Access Digital Assets ................................ 40

F. Address Digital Assets in a Will .............................................. 41

1. Disposition of Digital Assets ............................................. 41

2. Personal Representative Access to Digital Assets ............ 42

3. Other Digital Asset Concerns ........................................... 42

G. Place Digital Assets in a Trust ................................................ 43

H. Use Online Afterlife Company ................................................. 44

VIII. C

RYPTOCURRENCY ............................................................................ 46

A. Basics of Cryptocurrency ........................................................ 46

B. Benefits of Cryptocurrency ...................................................... 49

1. Security ............................................................................. 49

2. Privacy .............................................................................. 50

3. Shorter Transfer Delay, Lower Cost, and Finality of

Transfer ............................................................................. 51

C. Risks of Cryptocurrency .......................................................... 52

1. No Recovery Without Private Key or Seed Phrase ........... 52

2. Value Fluctuation .............................................................. 53

3. No Regulation ................................................................... 54

D. Prudent Investment and Fiduciary Concerns .......................... 55

E. Taxation and Classification of Cryptocurrency ...................... 55

F. Recommendations .................................................................... 58

IX. N

ON-FUNGIBLE TOKENS ................................................................... 60

A. What Is a Non-fungible Token? ............................................... 60

B. What Do NFTs Represent? ...................................................... 60

C. How Does a Person Create a NFT? ........................................ 61

D. Why Does a Person Create a NFT? ........................................ 61

E. I Am Still Confused. Are There Old-School Analogies That

May Help Me Understand NFTs? ........................................... 61

F. What Is the Value of a NFT? ................................................... 62

G. What Are Some Examples of Notable NFTs? .......................... 62

H. Other Than Collectibles, What Are Some Other Possible

Uses of NFTs? ......................................................................... 63

I. What Is the First Step I Need to Take Regarding NFTs When

Working with an Estate Planning Client? ............................... 63

J. What Type of Records Should a Client Keep About NFTs? .... 63

K. Is There a Special Concern If the Client Purchases a NFT

with Cryptocurrency? .............................................................. 63

L. Should the Client Consider Holding NFTs in a Business

Entity? ..................................................................................... 64

M. How Should the Client Protect the Information Needed to

Access NFTs? .......................................................................... 64

N. How Should a Client’s Will Address NFTs? ........................... 64

4 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

O. I Am a Personal Representative of a Decedent’s Estate. Can

I Access the Decedent’s NFTs? ............................................... 65

P. I Am a Personal Representative of a Decedent’s Estate. Is

There Anything Special Regarding NFTs About Which I

Should Be Immediately Concerned?........................................ 65

Q. I Am a Trustee. Can I Retain NFTs in a Trust or Invest in

NFTs? ...................................................................................... 65

R. Are There Any Religious-Based Considerations I Need to Keep

in Mind with Respect to NFTs? ............................................... 66

S. If I Plan on Advising Clients About NFTs, Is There Anything

Else You Would Recommend That I Do?................................. 66

T. If My Client Mints NFTs, Are There Any Additional Special

Warnings I Should Provide the Client? ................................... 67

U. Why Should a Charitable Organization Consider Accepting

NFT and Cryptocurrency Donations? ..................................... 67

V. Due to Their Volatile Nature, Is It Risky for Charitable

Organizations to Accept Crypto Assets? ................................. 68

W. How Can a Charitable Organization Accept Crypto

Donations? .............................................................................. 68

X. Are There Any Additional Considerations for Organizations

Wanting to Hold on to Crypto Donations? .............................. 69

Y. Are There Any Specific Reporting Requirements for Crypto

Donations? .............................................................................. 69

Z. How Are Crypto Assets Treated for Accounting Purposes? .... 69

AA. Do Crypto Assets Pose Any ESG Concerns for My

Organization? .......................................................................... 70

BB. Why Should My Client Consider Donating Crypto Assets? .... 70

CC. How Can My Client Receive a Charitable Contribution

Deduction from a Crypto Donation? ....................................... 71

DD. What Type of Crypto Assets Can Be Donated? ....................... 71

EE. What Are Some Future Issues I May Be Asked to Address

About NFTs? ............................................................................ 72

X. M

ETAVERSE ASSETS ......................................................................... 72

A. What Is the Metaverse? ........................................................... 72

B. What Are Some Early Uses of the Metaverse? ........................ 72

C. How Is the Metaverse Expanding Today? ............................... 72

D. Other Than Gaming Assets, What Is a Common Type of

Metaverse Property? ............................................................... 73

E. How Do I Address Metaverse Assets in a Client’s Estate? ..... 73

F. How Do I Address Metaverse Assets Held in Trust? ............... 74

XI. F

UTURE REFORM AREAS ................................................................... 74

A. Providers Gather User’s Actual Preferences .......................... 74

B. Congress Amends Federal Law ............................................... 75

C. States Enact RUFADAA .......................................................... 75

XII. C

ONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 76

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 5

A

PPENDIX A – DIGITAL ESTATE INFORMATION SAMPLE FORM ................. 77

A

PPENDIX B – SAMPLE DOCUMENT LANGUAGE ........................................ 82

A

PPENDIX C – SAMPLE REQUEST LETTER TO DIGITAL ASSET

C

USTODIAN ......................................................................................... 88

A

PPENDIX D – A PRIMER FOR PROBATE JUDGES ........................................ 90

A

PPENDIX E – SUMMARY OF STATE STATUTES .......................................... 94

6 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

I.

INTRODUCTION

For hundreds of years, we have viewed personal property as falling into

two major categories—tangible (items you can see or hold) and intangible

(items that lack physicality).

1

Recently, a new subdivision of personal

property has emerged that many label as “digital assets.”

2

There is no real

consensus about the property category in which digital assets belong.

3

Some

experts say they are intellectual property, some say they are intangible

property, and still others say they can easily be transformed from one form

of personal property to another with the click of a “print” button.

4

Digital assets may represent a sizeable portion of a client’s estate.

5

A

survey conducted by McAfee, Inc. revealed that the average perceived value

of digital assets for a person living in the United States is $54,722.

6

This Article aims to educate estate planning professionals on the

importance of planning for the disposition and administration of digital assets

so that fiduciaries can locate, access, protect, and properly dispose of them.

7

The operation of the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets

Act, now enacted in at least forty-five states, is explained in detail.

8

Several

planning techniques that may be employed are discussed, and the appendices

include sample forms clients may use to organize their digital assets, as well

as sample language that can be used in estate planning documents, court

orders, and request letters to digital asset custodians.

9

The Article also

includes coverage of cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

10

II.

TYPES OF DIGITAL ASSETS

The Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act

(RUFADAA) defines “digital asset” as “an electronic record in which an

individual has a right or interest; the term does not include an underlying

asset or liability unless the asset or liability is itself an electronic record.”

11

For purposes of this definition, “electronic” means “relating to technology

1. Gerry W. Beyer & Kerri G. Nipp, Cyber Estate Planning and Administration, SOC. SCI. RSCH.

NETWORK 1, 1, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2166422 (Mar. 30, 2022) [https://

perma.cc/V627-TJUN].

2. Id.

3. Id.

4. Id.

5. Id.

6. Id.; McAfee Reveals Average Internet User Has More Than $37,000 In Under-Protected ‘Digital

Assets’, C

HANNEL ASIA (Sept. 28, 2011), https://www.channelasia.tech/mediareleases/13079/mcafee-

reveals-average-internet-user-has-more/ [https://perma.cc/QJ35-U24E].

7. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 1.

8. Id.

9. Id.

10. Id.

11. Id.; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT § 2 (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 7

having electrical, digital, magnetic, wireless, optical, electro-magnetic, or

similar capabilities,” and “record” means “information that is inscribed on a

tangible medium or that is stored in an electronic or other medium and is

retrievable in perceivable form.”

12

Digital assets can be classified in numerous different ways, and the

types of property and accounts are constantly changing.

13

A decade ago, who

could have imagined the ubiquity of Facebook?

14

Who can imagine what will

replace it in the next few decades?

15

People may accumulate different

categories of digital assets: personal, social media, financial, and business.

16

Although there is some overlap, of course, clients may need to make different

plans for each type of digital asset.

17

A. Personal

The first category includes personal assets stored on a computer, tablet,

smart phone, or other digital device, as well as uploaded onto a website or on

a cloud storage account.

18

These can include treasured photographs or videos

stored on an individual’s hard drive or a photo sharing site such as Tinybeans

or Flickr.

19

Other examples include emails, texts, documents, music playlists,

medical records, tax documents, personal blogs, digital books, online gaming

or gambling assets, avatars, and recordings from home security systems.

20

The list of what a client could potentially own or control is, almost literally,

infinite.

21

B. Social Media

Social media assets involve interactions with other people with accounts

through providers such as Facebook, LinkedIn, X, YouTube, Instagram,

Reddit, Tumblr, and Pinterest.

22

These sites are used not only for messaging

and social interaction, but they also can serve as storage for documents,

photos, videos, and other electronic files.

23

12. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 1; REVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT § 2

(U

NIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

13. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 1.

14. Id.

15. Id.

16. Id.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Id.

20. Id. at 1–2.

21. Id. at 2.

22. Id.

23. Id.

8 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

C. Financial Accounts

The most obvious example of financial digital assets are virtual

currencies, which are becoming more prevalent and are addressed in more

detail in Part VIII below.

24

Though some bank and investment accounts have no connection to

brick-and-mortar buildings, most retain some connection to a physical

space.

25

They are, however, increasingly designed to be accessed via the

internet with few, if any, paper records or monthly statements.

26

For example,

an individual can maintain an Amazon.com account, have an eBay account,

be registered with PayPal, and subscribe to online magazines and other media

providers.

27

Many people make extensive arrangements to pay bills online such as

income taxes, mortgages, car loans, credit cards, water, gas, telephone, cell

phone, cable, and trash disposal.

28

These individuals may not receive

traditional paper statements via the United States Postal Service regarding

these accounts.

29

D. Business Accounts

An individual engaged in any type of commercial practice is likely to

store some information on computers.

30

Businesses collect data such as

customer orders and preferences, home and shipping addresses, credit card

data, bank account numbers, and even personal information such as

birthdates and the names of family members and friends.

31

Physicians store

patient information; eBay sellers have an established presence and

reputation.

32

Lawyers might store client files or use a Dropbox.com-type

service that allows a legal team spread across the United States to access

litigation documents through shared folders.

33

E. Domain Names or Blogs

A domain name or blog can be valuable, yet access and renewal may

only be possible through a password or email.

34

24. Id.; see infra Part VII.

25. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 2.

26. Id.

27. Id.

28. Id.

29. Id.

30. Id.

31. Id.

32. Id.

33. Id.

34. Id.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 9

F. Loyalty Program Benefits

In today’s highly competitive business environment, there are numerous

options for customers to make the most of their travel and spending habits,

especially if they are loyal to particular providers.

35

Airlines have created

programs in which frequent flyers accumulate “miles” or “points” they may

use towards free or discounted trips.

36

Some credit card companies offer users

an opportunity to earn “cash back” on their purchases or accumulate points

which the cardholder may then use for discounted merchandise, travel, or

services.

37

Retail stores often allow shoppers to accumulate benefits

including discounts and credit vouchers.

38

Some members of these programs

accumulate a staggering amount of points or miles and then die without

having “spent” them.

39

For example, there are reports that “members of

frequent-flyer programs are holding at least 3.5 trillion in unused miles.”

40

The rules of the loyalty program to which the client belongs play the

key role in determining whether the accrued points may be transferred.

41

Many customer loyalty programs do not allow transfer of accrued points

upon death, but, as long as the beneficiary knows the online login information

of the member, it may be possible for the remaining benefits to be transferred

or redeemed.

42

However, some loyalty programs may view this redemption

method as fraudulent or require that certain paperwork be filed before

authorizing the redemption of remaining benefits.

43

III.

IMPORTANCE OF PLANNING FOR DIGITAL ASSETS

A. To Make Things Easier on Executors and Family Members

When individuals are prudent about their online lives they have many

different usernames and passwords for their digital assets.

44

Each digital asset

may require a different means of access—simply logging onto someone’s

computer generally requires a password, perhaps a different password for

operating system access, and then each of the different files on the computer

may require its own password.

45

Each online account is likely to have its own

35. Id.

36. Id.

37. Id.

38. Id.

39. Id.

40. Id.; Managing Your Frequent-Flyer Miles, GROCO, https://groco.com/article/managing-your-

frequent-flyer-miles/ (last visited Nov. 20, 2023) [https://perma.cc/ZB5Y-7K4C].

41. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 2.

42. Id.

43. Id.

44. Id. at 3.

45. Id.

10 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

username, password, and security questions and answers.

46

Some devices and

apps have biometric verification, such as fingerprint scanning, iris

recognition, or face recognition.

47

This is the only way to secure identities,

but this devotion to protecting sensitive personal information can wreak

havoc on families and fiduciaries upon incapacity or death.

48

Consider the well-publicized “Ellsworth case.”

49

After Lance Cpl. Justin

Ellsworth was killed in 2004 while serving with the United States Marine

Corps in Afghanistan, his parents began a legal battle with Yahoo! to gain

access to messages stored in his email account.

50

However, the family

remained disappointed when the data CD provided by Yahoo! contained only

received emails and none their late son had written.

51

Had Justin provided

guidance to his family members regarding his digital assets, his family may

have been able to avoid the expense and trouble of going to court, and they

also might have gained access to all the emails they desired to have, rather

than just some.

52

In addition, many individuals no longer receive paper statements or

bills, instead receiving everything via email or by logging on to a service

provider’s online account.

53

Without instructions from a client, locating,

collecting, and monitoring these assets will be a burdensome task for the

client’s family members and fiduciaries.

54

Despite legislation addressing fiduciaries’ ability to access and manage

digital assets (discussed below), the rights of executors, agents, guardians,

and beneficiaries regarding digital assets are still unclear.

55

The more clients

plan in advance for digital assets, the better chance their fiduciaries will have

to be able to efficiently access and administer such assets.

56

B. To Prevent Identity Theft

In addition to needing access to online accounts for personal reasons

and closing probate, family members need this information quickly so that a

deceased’s identity is not stolen.

57

Until authorities update their databases

regarding a new death, criminals can open credit cards, apply for jobs, and

46. Id.

47. Id.

48. Id.

49. Id.

50. Id.; see Stefanie Olsen, Yahoo releases e-mail of deceased Marine, ZDNET (Apr. 21, 2005,

12:39 PM), https://www.zdnet.com/article/yahoo-releases-e-mail-of-deceased-marine/ [https://perma.cc/

V6RG-H5LJ].

51. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 3; Olsen, supra note 50.

52. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 3; Olsen, supra note 50.

53. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 3.

54. Id.

55. Id.; see infra Part VI.

56. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 3.

57. Id.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 11

get state identification cards under a dead person’s name.

58

A fraud

prevention firm by the name of ID Analytics conducted a study in 2012 and

found that approximately 2.5 million deceased Americans have their identity

stolen each year.

59

Criminals know that they have a window of opportunity

when someone passes away, so they search through obituaries and other

death databases to locate new victims.

60

C. To Prevent Financial Losses to the Estate

1. Bill Payment and Online Sales

Electronic bills for utilities, loans, insurance, and other expenses need

to be discovered quickly and paid to prevent cancellations.

61

This concern is

augmented further if the deceased or incapacitated individual conducted an

online business and is the only person with access to incoming orders, the

servers, corporate bank accounts, and employee payroll accounts.

62

2. Domain Names

The decedent may have registered one or more domain names that have

commercial value.

63

If registration of these domain names is not kept current,

they can easily be lost to someone waiting to snag the name upon a lapsed

registration.

64

Here is list of some of the most expensive domain names that

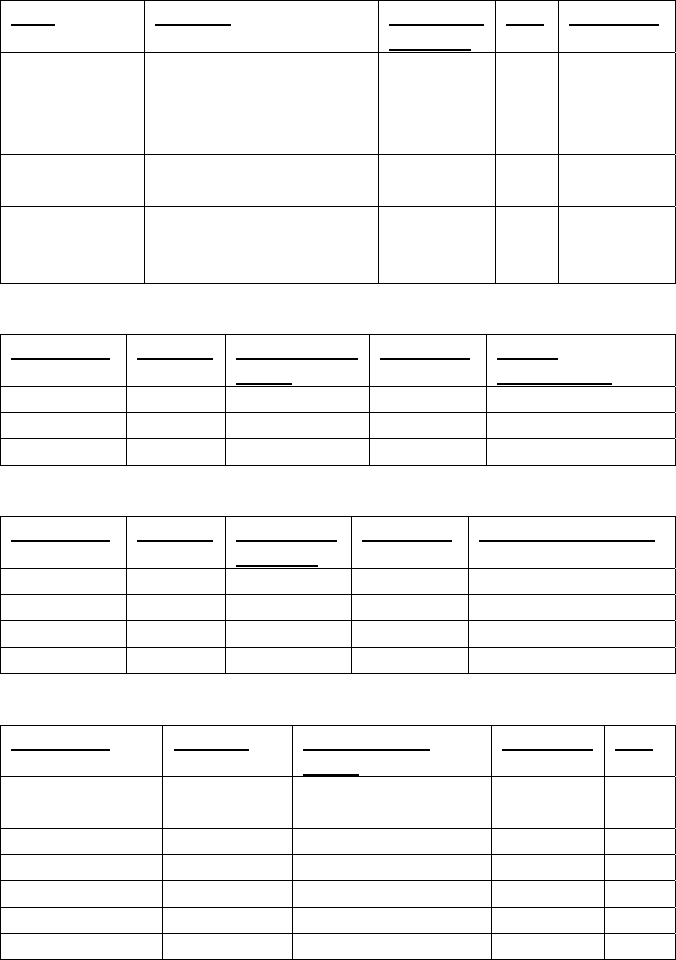

have been sold in recent years:

1. Voice.com $30 million 2019

65

2. 360.co

m

$17 million 2015

66

3. NFTs.com $15 million 2022

67

58. Id.

59. Id.; see Martha C. White, Grave Robbing: 2.5 Million Dead People Get Their Identities Stolen

Every Year, T

IME (Apr. 24, 2012), https://business.time.com/2012/04/24/grave-robbing-2-5-million-

dead-people-get-their-identities-stolen-every-year/ [https://perma.cc/2SM7-WNY4].

60. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 3.

61. Id.

62. Id.

63. Id. at 4.

64. Id.

65. Id.; Andrew Allemann, Record breaker: Voice.com domain name sells for staggering $30

million, D

OMAIN NAME WIRE (June 18, 2019), https://domainnamewire.com/2019/06/18/record-breaker-

voice-com-domain-name-sells-for-staggering-30-million/ [https://perma.cc/TC69-38KM].

66. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Doug Young, Qihoo Eyes 360 Brand With Record Domain

Buy, F

ORBES (Feb. 6, 2015, 7:45 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/dougyoung/2015/02/06/qihoo-eyes-

360-brand-with-record-domain-buy/?sh=3eaba7c94016 [https://perma.cc/P7P7-QS7D].

67. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Andrew Allemann, NFTs.com domain sells for whopping $15

million, D

OMAIN NAME WIRE (Aug. 3, 2022), https://domainnamewire.com/2022/08/03/nfts-com-

domain-sells-for-whopping-15-million/ [https://perma.cc/A6WQ-T3CC].

12 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

4. Sex.com $13 million 2010

68

5. Hotels.com $11 million 2001

69

6. Tesla.com $11 million 2016

70

7. AI.com $11 million 2023

71

8. Fund.co

m

$10 million 2008

72

9. Connect.com $10 million 2022

73

10. Porno.co

m

$8.8 million 2015

74

11. Fb.com $8.5 million 2010

75

12. HealthInsurance.com $8.13 million 2019

76

13. We.com $8 million 2014

77

14. iCloud.com $6 million 2011

78

15. Casino.com $5.5 million 2003

79

16. Slots.com $5.5 million 2010

80

68. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Andrew Allemann, Sex.com is for sale (again), DOMAIN NAME

WIRE (Jan. 18, 2023), https://domainnamewire.com/2023/01/18/sex-com-is-for-sale-again/ [https://perma

.cc/2335-38N4].

69. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Elliot Silver, BBC: Hotels.com Domain Name Original Bought

for $11 Million, D

OMAININVESTING.COM (Nov. 2, 2012), https://domaininvesting.com/bbc-hotels-com-

domain-name-originally-bought-for-11-million/ [https://perma.cc/L7Y7-64DE].

70. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Elliot Silver, Elon Musk on What it Took to Acquire Tesla.com,

D

OMAININVESTING.COM (Dec. 9, 2018), https://domaininvesting.com/elon-musk-on-what-it-took-to-

acquire-tesla-com/ [https://perma.cc/UC2X-BP54].

71. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Nickie Louise, OpenAI buys AI.com for $11 million, making

it one of the top 10 most expensive domains ever sold, T

ECH STARTUPS (Mar. 1, 2023),

https://techstartups.com/2023/03/01/openai-buys-ai-com-for-11-million-making-it-one-of-the-top-10-

most-expensive-domains-ever-sold/ [https://perma.cc/6VUS-WECG].

72. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Elliot Silver, Fund.com Sold via Media Options,

D

OMAININVESTING.COM (Jan. 11, 2019), https://domaininvesting.com/fund-com-sold-via-media-options/

[https://perma.cc/W33J-8549].

73. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Andrew Allemann, Hubspot acquired connect.com domain

for $10 million, D

OMAIN NAME WIRE (Aug. 7, 2022), https://domainnamewire.com/2022/08/07/hubspot-

acquired-connect-com-domain-for-10-million/ [https://perma.cc/4TJ9-NHPX].

74. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Michael Berkens, Rick Schwartz Sells Porno.Com For

$8,888,888: The 4th Highest Reported Domain Sale Of All Time, T

HE DOMAINS (Feb. 2, 2015),

https://www.thedomains.com/2015/02/02/rick-schwartz-sells-porno-com-for-8888888-the-4th-highest-

reported-domain-sale-of-all-time/ [https://perma.cc/RKY6-UYYM].

75. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Ben Parr, Facebook Paid $8.5 Million to Acquire Fb.com,

M

ASHABLE (Jan. 12, 2011), https://mashable.com/archive/facebook-paid-8-5-million-to-acquire-fb-com

[https://perma.cc/S7JU-UPNU].

76. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Elliot Silver, Benefytt Technologies Inc. Talks About

HealthInsurance.com, D

OMAININVESTING.COM (Mar. 10, 2020), https://domaininvesting.com/benefytt-

technologies-inc-talks-about-healthinsurance-com/ [https://perma.cc/N6CA-NTUS].

77. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Joe Styler, The top 25 most expensive domain names,

G

ODADDY (July 14, 2022), https://www.godaddy.com/resources/skills/the-top-20-most-expensive-

domain-names [https://perma.cc/ZHR2-6GBA].

78. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Styler, supra note 77.

79. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Styler, supra note 77.

80. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Styler, supra note 77.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 13

17. AsSeenOnTv.com $5.1 million 2000

81

18. Toys.com $5.1 million 2009

82

19. Clothes.com $4.9 million 2008

83

20. Medicare.com $4.8 million 2014

84

3. Encrypted Files

Some digital assets of value may be lost if they cannot be decrypted.

85

Consider the case of Leonard Bernstein who died in 1990 leaving the

manuscript for his memoir entitled Blue Ink on his computer in a

password-protected file.

86

To this day, as far as these authors can ascertain,

no one has been able to break the password and access what may be a very

interesting and valuable document.

87

4. Virtual Property

The decedent may have accumulated valuable virtual property for use

in online games.

88

If monthly usage or subscription fees apply and are not

paid, this virtual property could be lost.

89

Your client may also have the potential of winning large prizes in video

game tournaments.

90

In 2017, reports indicate that over $100 million in

gaming prizes were awarded.

91

D. To Avoid Losing the Deceased’s Personal Story

Many digital assets are not inherently valuable but are valuable to family

members who extract meaning from what the deceased leaves behind.

92

Historically, people kept special pictures, letters, and journals in shoeboxes

or albums for future heirs.

93

Today, this material is stored on computers or

81. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Joe Uddeme, Most Expensive Domain Names: 25 of the

Highest Domains Ever Sold, N

AMEEXPERTS.COM, https://nameexperts.com/blog/25-of-the-most-

expensive-domain-names-ever-sold/ (last visited Oct. 20, 2023) [https://perma.cc/VQ7Y-S3WR].

82. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Uddeme, supra note 81.

83. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Uddeme, supra note 81.

84. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4; Uddeme, supra note 81.

85. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 4.

86. Id.

87. Id.

88. Id.

89. Id.

90. Id.

91. Id.

92. Id.

93. Id.

14 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

online and is often never printed.

94

Personal blogs and X (previously known

as Twitter) feeds have replaced physical diaries, and emails and texts have

replaced letters.

95

Without alerting family members that these assets exist,

and without telling them how to get access to them, the story of the life of the

deceased may be lost forever.

96

This is not only a tragedy for family members

but also possibly for future historians who are losing pieces of history in the

digital abyss.

97

For more active online lives, this concern may also involve preventing

spam from infiltrating a loved one’s website or blog site.

98

Comments from

friends and family are normally welcomed, but it is jarring to discover the

comment thread gradually infiltrated with links for “cheap Ugg boots.”

99

“It’s

like finding a flier for a dry cleaner stuck among flowers on a grave, except

that it is much harder to remove.”

100

In the alternative, family members may

decide to delete the deceased’s website against the deceased’s wishes simply

because those wishes were not expressed to the family.

101

E. To Prevent Unwanted Secrets from Being Discovered

Sometimes people do not want their loved ones discovering private

emails, documents, or other electronic material.

102

They may contain hurtful

secrets, politically incorrect jokes and stories, or personal rantings.

103

Decedents may have a collection of adult recreational material (porn) which

they would not want others to know had been accumulated.

104

A professional,

such as an attorney or physician, is likely to have files containing confidential

client information.

105

Without designating appropriate people to take care of

electronically stored materials, the wrong person may come across this type

of information and use it in an inappropriate or embarrassing manner.

106

F. To Prepare for an Increasingly Information-Drenched Culture

Although the principal concern today appears to be the disposition of

social media and email contents, the importance of planning for digital assets

94. Id.

95. Id.

96. Id.

97. Id. at 4–5.

98. Id. at 5.

99. Id.; Rob Walker, Cyberspace When You’re Dead, N.Y.

TIMES MAG. (Jan. 5, 2011),

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/magazine/09Immortality-t.html [https://perma.cc/3X8F-29V2].

100. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 5; Walker, supra note 99.

101. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 5.

102. Id.

103. Id.

104. Id.

105. Id.

106. Id.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 15

will increase each day.

107

Online information will continue to spread out

across a growing array of flash drives, iPhones, and cloud accounts, and it

will be more difficult to locate and accumulate.

108

As people invest more

information about their activities, health, and collective experiences into

digital media the legacies of digital lives grow increasingly important.

109

If a

foundation for planning for these assets is not set today, we may re-learn the

lesson that the Rosetta Stone once taught us: there is no present tense that can

long survive the fall and rise of languages and modes of recordkeeping.

110

IV.

OBSTACLES TO PLANNING FOR DIGITAL ASSETS

Including digital assets in estate plans is a relatively new phenomenon,

and there are several obstacles that make it difficult to plan for them.

111

Some

of the problem areas include user agreements, federal law, safety issues

involved with passwords, the hassle of updating this information, the

uncertainty surrounding online afterlife management companies, and the fact

that some online afterlife management companies overstate their abilities.

112

A. User Agreements

1. Terms of Service Agreements

When an individual signs up for a new online account or service, the

process typically requires an agreement to the provider’s terms of service.

113

Service providers may have policies on what will happen on the death of an

account holder, but individuals rarely read the terms of service carefully, if

at all.

114

Nonetheless, the user is at least theoretically made aware of these

policies before being able to access any service.

115

Anyone who has signed

up for an online service has probably clicked on a box next to an “I agree”

statement near the bottom of a web page or pop-up window signifying

consent to the provider’s terms of service agreement (TOSA).

116

The terms

of these “clickwrap” agreements are typically upheld by the courts.

117

107. Id.

108. Id.

109. Id.

110. Id. (noting the meaning of the Rosetta Stone’s hieroglyphs detailing the accomplishments of

Ptolemy V were lost for fifteen centuries when society neglected to safeguard the path to deciphering the

writings; a Napoleonic soldier eventually discovered the triptych, enabling society to recover its writings).

111. Id.

112. Id.

113. Id.

114. Id.

115. Id.

116. Id.

117. Id.

16 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

For example, at the end of its TOSA, Yahoo! explicitly states that an

account cannot be transferred: “[A]ll Yahoo accounts are non-transferable,

and any rights to them terminate upon the account holder’s death.”

118

2. Ownership

A problem may also arise if the client does not actually own the digital

asset but merely has a license to use that asset while alive.

119

It is unlikely a

person can transfer to heirs or beneficiaries music, movies, and books they

have purchased in electronic form, although they may transfer “old school”

physical records (vinyl), CDs, DVDs, books, etc. without difficulty.

120

It has

been reported that actor Bruce Willis wants to leave his large iTunes music

collection to his children, but Apple’s user agreement prohibits him from

doing so.

121

Apple’s terms and conditions grant the user a license to use their

services but expressly prohibit transfers, making it clear that services “are

licensed, not sold, to you,” and that Apple “grants to you a nontransferable

license.”

122

B. Federal Law

There are two primary federal laws that are relevant in the discussion

regarding a fiduciary’s access to digital assets: (1) the Stored

Communications Act, a federal privacy law, and (2) the Computer Fraud and

Abuse Act, a federal criminal law.

123

1. Stored Communications Act

The Stored Communications Act (SCA) was enacted in 1986 as part of

the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA).

124

It regulates access to

and disclosure of stored electronic communications and was an effort by

Congress to deal with the consequences of online communications upon

Fourth Amendment privacy protections.

125

The SCA provides for criminal

penalties to be imposed on anyone who “intentionally accesses without

authorization a facility through which an electronic communication service

is provided” or “intentionally exceeds an authorization to access that facility”

118. See id. at 5–6; Yahoo Terms of Service, YAHOO!, https://legal.yahoo.com/us/en/yahoo/terms/

otos/index.html (Oct. 6, 2023) [https://perma.cc/K3EY-TEKC].

119. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6.

120. Id.

121. Id.

122. Id.; Apple Media Services Terms and Conditions, A

PPLE, https://www.apple.com/legal/internet-

services/itunes/us/terms.html (Sept. 18, 2023) [https://perma.cc/MNS2-GNCN].

123. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6.

124. Id.; 18 U.S.C. §§ 2701–2713.

125. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; 18 U.S.C. §§ 2701–2713.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 17

and “thereby obtains, alters, or prevents authorized access to a wire or

electronic communication while it is in electronic storage in such system.”

126

In addition, the SCA prohibits an electronic communication service

provider or a remote computing service provider from knowingly divulging

the contents of a communication that is stored by, carried through, or

maintained on that service unless disclosure is made “with the lawful consent

of the originator or an addressee or intended recipient of such

communication, or the subscriber in the case of remote computing

service.”

127

a. In re Facebook, Inc. (Daftary Case)

The Federal District Court for the Northern District of California

applied the SCA in the Daftary Case where the personal representative of a

decedent’s estate attempted to compel Facebook to turn over contents of the

decedent’s account under the belief that the account held evidence the

decedent did not commit suicide and was instead murdered.

128

The court

noted that under the SCA, lawful consent to disclosure may permit a

custodian to disclose electronic communications, but it does not require such

disclosure, and therefore, Facebook could not be compelled to turn over the

contents.

129

The court specifically declined to decide whether the personal

representatives could provide sufficient “lawful consent” under the SCA, but

it also noted that Facebook could determine on its own that the personal

representative had standing to consent to disclosure and provide the requested

materials voluntarily.

130

b. Ajemian v. Yahoo!

On October 16, 2017, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts

became the first court to answer the question of whether a personal

representative of a deceased individual may grant “lawful consent” on behalf

of the deceased individual for purposes of the SCA.

131

In a tremendous win

for fiduciaries, the court answered the question in the affirmative, firmly

repudiating the position of service providers that the SCA prohibits such

disclosure.

132

However, the court’s decision echoed the Daftary court’s

sentiment that even with lawful consent from a personal representative, the

SCA does not require Yahoo! to disclose the decedent’s email account

126. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; 18 U.S.C. § 2701(a).

127. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; 18 U.S.C. § 2702(b)(3).

128. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; In re Facebook, Inc., 923 F. Supp. 2d 1204, 1205 (N.D. Cal.

2012).

129. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; In re Facebook, Inc., 923 F. Supp. 2d at 1206.

130. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 6; In re Facebook, Inc., 923 F. Supp. 2d at 1206.

131. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; Ajemian v. Yahoo!, Inc., 84 N.E.3d 169, 773–74 (2017).

132. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; Ajemian, 84 N.E.3d at 773–74.

18 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

content to the personal representatives; it merely holds that the SCA permits

the disclosure.

133

The court remanded one portion of the case to the probate court to

determine whether the Yahoo! TOSA prevents disclosure.

134

It is anticipated

that the probate court, on remand, will issue an order mandating that Yahoo!

disclose the contents of the account now that the Supreme Judicial Court has

confirmed that the personal representatives may provide Yahoo! with lawful

consent under the SCA.

135

The United States Supreme Court denied Yahoo!’s

petition for a writ of certiorari on March 26, 2018.

136

2. Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) was also enacted by

Congress in 1986.

137

It states that anyone who “intentionally accesses a

computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access” has committed

a crime.

138

A basic violation of the CFAA is a misdemeanor but can become

a felony if done for profit or in furtherance of another crime or tort.

139

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) asserts that the CFAA

allows the government to charge an individual with a crime for violating the

CFAA if such individual violates the access rules of a service provider’s

TOSA.

140

“This position was stated by Richard Downing, Deputy Chief of

the DOJ’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section, Criminal

Division, in testimony presented on November 15, 2011, before the U.S.

House Committee on Judiciary, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and

National Security.”

141

However, Mr. Downing also made it clear that the DOJ

is not interested in prosecuting minor violations.

142

3. Interface with User Agreements

Note that both federal statutes described above provide an exception—

if an individual has lawful consent or authorization to access an electronic

communication (SCA) or a computer (CFAA), that individual is not

133. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; Ajemian, 84 N.E.3d at 773–74.

134. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; Ajemian, 84 N.E.3d at 773–74.

135. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7.

136. Id.

137. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a).

138. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; see 18 U.S.C. § 1030.

139. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; see 18 U.S.C. § 1030.

140. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7.

141. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7; Jim Lamm, Two New Cases on Using Computers “Without

Authorization” under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, D

IGIT. PASSING (July 18, 2016),

http://www.digitalpassing.com/2016/07/18/new-cases-using-computers-without-authorization-under-

computer-fraud-abuse-act/ [https://perma.cc/36LN-QDFQ].

142. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 7.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 19

committing a crime.

143

However, the issue is that most service providers’

TOSAs prohibit users from granting anyone else access to their accounts.

144

If the user does not have the ability to give lawful consent, then the person

accessing the account is by default exceeding authorized access.

145

Compounding the issue, many providers retain the right to change their

TOSAs at any time and without notice to the user.

146

Therefore, a fiduciary’s

access to an account may be a permitted act one day but become a criminal

act the next just because a service provider makes a change to its TOSA.

147

Neither the SCA nor the CFAA was intended to address fiduciaries’

access to digital assets, but it is easy to see why the statutes have a significant

chilling effect on fiduciaries attempting to access certain digital assets.

148

These statutes are complicated, and their application to emails and social

networking sites has sparked additional confusion.

149

There have been

infinite technological advances since 1986, yet Congress has not updated the

statutes to conform to modern technology.

150

The American College of Trust and Estate Counsel (ACTEC) has

drafted language that would fix both statutes for estate planning purposes.

151

The revisions are simple and include adding a definition to both the SCA and

the CFAA, as well as adding one additional sentence to the SCA.

152

The problem of fiduciary access possibly being in violation of the law

is also an issue in other nations, such as the United Kingdom, where using a

deceased’s username and password could result in the person who gains

access violating the Computer Misuse Act of 1990.

153

C. Safety Concerns

Clients may be hesitant to place all of their usernames, passwords, and

other information in one place.

154

We have all been warned, “Never write

down your passwords.”

155

This document could fall into the hands of the

wrong person, leaving your client exposed.

156

With an online afterlife

143. Id.

144. Id.

145. Id.

146. Id.

147. Id.

148. Id.

149. Id.

150. Id.

151. Id.

152. Id. at 7–8.

153. Id. at 8; The Newsroom, Aileen Entwistle: Safeguarding your online legacy after you’ve gone,

T

HE SCOTSMAN: BUS. (Mar. 30, 2013, 1:10 PM), https://www.scotsman.com/business/aileen-entwistle-

safeguarding-your-online-legacy-after-youve-gone-1582460 [https://perma.cc/8FB4-TD9P].

154. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 8.

155. Id.

156. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 8.

20 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

management company or an online password vault, clients may worry that

the security system could be breached, leaving them completely exposed.

157

D. Hassle

Planning for digital assets is an unwanted burden.

158

Digital asset

information is constantly changing and may be stored on a variety of devices

(e.g., desktop computers, laptop computers, smart phones, cameras, iPads,

CDs, DVDs, and flash drives).

159

A client may routinely open new email

accounts, new social networking or gaming accounts, or change

passwords.

160

Documents with this information must be revised, and accounts

at online afterlife management companies must be frequently updated.

161

For

clients who wish to keep this information in a document, advise them to

update the document quarterly and save it to a USB flash drive or on the

cloud, making sure that a family member, friend, or attorney knows where to

locate it.

162

E. Uncertain Reliability of Online Afterlife Management Companies

Afterlife management companies come and go; their life is dependent

upon the whims and attention spans of their creators and creditors.

163

Lack of

sustained existence of all of these companies makes it hard, if not impossible,

to determine whether this market will remain viable.

164

Clients may not want

to spend money to save digital asset information when they are unsure about

the reliability of the companies.

165

F. Overstatement of the Abilities of Online Afterlife Management

Companies

Some of these companies claim they can distribute digital assets to

beneficiaries upon your client’s death.

166

Clients need to understand that

these companies cannot do this legally; the client needs a will to transfer

assets, no matter what kind.

167

Using these companies to store information to

make the probate process easier could be an effective technique, but these

157. Id.

158. Id.

159. Id.

160. Id.

161. Id.

162. Id.

163. Id.

164. Id.

165. Id.

166. Id.

167. Id.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 21

companies cannot be used to avoid probate altogether.

168

David Shulman, an

estate planner in Florida, stated that he “would relish the opportunity to

represent the surviving spouse of a decedent whose eBay business was ‘given

away’ by Legacy Locker to an online friend in Timbuktu.”

169

V.

BRIEF HISTORY OF FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGITAL ASSETS

The rights of executors, administrators, agents, trustees, and guardians

to access digital assets of the decedent, principal, beneficiary, or ward has

seen rapid development since California first touched on the issue in 2002.

170

This section briefly discusses prior legislation to help place the current

majority law, RUFADAA, into perspective.

171

A. Early State Law

States began to recognize the need to plan for digital assets and to

provide clarity in this area of the law as early as 2002.

172

This legislation took

a variety of forms and can be divided into different “generations.”

173

1. First Generation

The first-generation statutes only covered email accounts.

174

They did

not contain provisions enabling or permitting access to any other type of

digital asset.

175

California. The first and most primitive first-generation statute was

enacted by California in 2002.

176

It simply provided, “Unless otherwise

permitted by law or contract, any provider of electronic mail service shall

provide each customer with notice at least 30 days before permanently

terminating the customer’s electronic mail address.”

177

In 2016, California

enacted the decedent’s estates and trusts provisions of RUFADAA.

178

Connecticut. Connecticut was one of the first states to address

executors’ rights to digital assets in 2005 with Senate Bill 262, requiring

168. Id.

169. Id.; David Shulman, Estate Planning for Your Digital Life, or, Why Legacy Locker Is a Big Fat

Lawsuit Waiting to Happen, G

INSBERG SHULMAN ATT’YS AT L. (Mar. 20, 2009), https://www.ginsberg

shulman.com/blog/estate-planning-for-your-digital-life-or-why-legacy-locker-is-a-big-fat-lawsuit-waitin

g-to-happen/ [https://perma.cc/9LKG-969L].

170. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 8.

171. Id.

172. Id. at 9.

173. Id.

174. Id.

175. Id.

176. Id.

177. Id.; C

AL. BUS. & PROF. CODE § 17538.35 (West 2010).

178. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9.

22 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

“electronic mail providers” to allow executors and administrators “access to

or copies of the contents of the electronic mail account” of the deceased upon

a showing of the death certificate and a certified copy of the certificate of

appointment as executor or administrator or by court order.

179

The bill

specifically defined “electronic mail service providers” as “sending or

receiving electronic mail” on behalf of end-users.

180

In 2016, Connecticut

enacted RUFADAA.

181

Rhode Island. In 2007, Rhode Island passed the Access to Decedents’

Electronic Mail Accounts Act, requiring “electronic mail service providers”

to provide executors and administrators “access to or copies of the contents

of the electronic mail account” of the deceased upon showing of the death

certificate and certificate of appointment as executor or administrator or by

court order.

182

In 2019, Rhode Island enacted RUFADAA.

183

2. Second Generation

Indiana. Perhaps in acknowledgement of changing technological times

and the need to address more than just email accounts, Indiana enacted a

second-generation statute in 2007, which required custodians of records

“stored electronically” regarding or for Indiana-domiciled decedents to

release such records upon request to the personal decedent’s personal

representative.

184

3. Third Generation

Third-generation legislation (enacted in Oklahoma, Idaho, Nevada, and

Louisiana) acknowledged the changes to the digital asset landscape and

expressly recognized social networking and microblogging as digital

assets.

185

Oklahoma. In 2010, Oklahoma enacted legislation with a fairly broad

scope, giving executors and administrators “the power . . . to take control of,

conduct, continue, or terminate any accounts of a deceased person on any

social networking website, any microblogging or short message service

website or any e-mail service websites.”

186

Idaho. On March 26, 2012, Idaho amended its Uniform Probate Code

to enable personal representatives and conservators to “[t]ake control of,

179. Id.; S.B. 262, 2005 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Conn. 2005) (codified at CONN. GEN. STAT. § 45a-334a

(2012)).

180. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9.

181. Id.

182. Id.; 33 R.I.

GEN. LAWS § 33-27-3 (2012).

183. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9.

184. Id.; I

ND. CODE § 29-1-13-1.1 (2016).

185. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9.

186. Id.; O

KLA. STAT. tit. 58, § 269 (2012).

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 23

conduct, continue or terminate any accounts of the decedent on any social

networking website, any microblogging or short message service website or

any e-mail service website.”

187

Nevada. In 2013, Nevada enacted Nevada 2013 Session Laws chapter

325 authorizing a personal representative to direct the termination of, but not

access to, email, social networking, and similar accounts.

188

Nevada adopted

RUFADAA in 2017.

189

Louisiana. In 2014, Louisiana granted succession representatives the

right to obtain access or possession of a decedent’s digital accounts within

thirty days after receipt of letters.

190

The statute attempts to trump contrary

provisions of service agreements by deeming the succession representative

to be an authorized user who has the decedent’s lawful consent to access and

possess the accounts.

191

B. First Attempt at a Uniform Act

As the years passed, state legislation became increasingly

comprehensive, but the laws also became more and more different from one

another.

192

The conflicting laws were compounding the issues as questions

arose regarding which state’s law should apply.

193

The National Conference

of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL) recognized the need

for a uniform act to address fiduciary access to digital assets and to provide

uniformity among the states.

194

Many states that were considering legislation

stopped in their tracks when the NCCUSL announced it would be drafting a

uniform act in 2012.

195

In the beginning, the NCCUSL was working with representatives of

Facebook and industry trade associations to develop the model act, but they

parted ways and each started working on a separate model act.

196

The

NCCUSL was the first to introduce its act, which it approved as the Uniform

Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (UFADAA) on July 29, 2014.

197

The

goal of UFADAA was to resolve as many of the impediments to fiduciary

access to and management of digital assets as possible by reinforcing the

notion that the fiduciary steps into the shoes of the accountholder and should

187. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9; S.B. 1044, 61st Leg., Reg. Sess. (Idaho 2011).

188. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9; N

EV. REV .STAT. § 1524 (2013).

189. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 9.

190. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 10; L

A. CIV. CODE ANN. art. 3191 (2023).

191. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 10; L

A. CIV. CODE ANN. art. 3191.

192. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 10.

193. Id.

194. Id.

195. Id.

196. Id.

197. Id.

24 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

be able to do everything with the account that the accountholder could have

done.

198

Delaware was the only state to enact a version of UFADAA.

199

Delaware’s version of the law was based off of a draft version of the model

act prior to it being finalized, but the NCCUSL considered it “close enough”

and designated it an enactment of the model act.

200

After Delaware’s

enactment, twenty-six other states introduced the act, but it froze in all states

due to massive opposition from the technology industry and privacy

advocates.

201

Various online service providers, civil liberties

organizations, and state bar sections voiced their concerns about UFADAA

to state legislators and governors.

202

Their primary concerns were that

UFADAA resulted in an invasion of privacy, conflicted with the SCA, and

included an improper override of the service providers’ TOSAs.

203

C. Privacy Expectation Afterlife and Choices Act

In response to UFADAA, NetChoice, an association of internet

companies that includes Google and Facebook, released its model act entitled

the Privacy Expectation Afterlife and Choices Act (PEAC).

204

[PEAC required] companies to disclose contents only when a court finds

that the user is deceased, and that the account in question has been clearly

linked to the deceased. Additionally, the request for disclosure must be

“narrowly tailored to effect the purpose of the administration of the estate,”

and the executor demonstrates that the information is necessary to resolve

the fiscal administration of the estate. And even then, the amount of

information is further restricted to the year preceding the date of death. This

is stringent guidance meant to protect the privacy of those who

communicated with the user while also ensuring that their loved ones can

access important financial statements that may be delivered to the

account.

205

A modified version of PEAC was enacted in Virginia, effective as of

July 1, 2015.

206

Virginia’s version of PEAC was later repealed and replaced

198. Id.

199. Id.; see D

EL. CODE ANN. tit. 12, §§ 5001–5007 (2015).

200. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 10.

201. Id.

202. Id.

203. Id.

204. Id.

205. Alethea Lange, Everybody Dies: What is Your Digital Legacy?, C

TR. FOR DEMOCRACY & TECH.:

PRIV. & DATA (Jan. 23, 2015), https://cdt.org/insights/everybody-dies-what-is-your-digital-legacy/

[https://perma.cc/HM9C-L7H9].

206. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 10.

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 25

by RUFADAA.

207

It was introduced in California and Oregon, and New York

introduced a bill that incorporated some provisions from PEAC.

208

None of

these bills were enacted, and PEAC flatlined as well, primarily due to its

inadequacies (it only addressed personal representatives of estates and did

not address other fiduciaries) and the fact that it was unworkable for

fiduciaries (e.g., requiring personal representatives to get a court order if

access was needed).

209

VI.

REVISED UNIFORM FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGITAL ASSETS ACT

In response to the overwhelming failure of both model acts, service

providers and the NCCUSL entered negotiations to find a compromise.

210

The result was the NCCUSL approving the Revised Uniform Fiduciary

Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA) at its July 2015 Annual

Conference.

211

This revision is a substantial rewrite with significant changes

in presumptions and procedures.

212

Unlike the original UFADAA, which granted fiduciaries presumptive

authority to access digital assets, RUFADAA places great emphasis upon

whether the deceased or incapacitated user expressly consented to the

disclosure of the content of the digital assets, either through what

RUFADAA refers to as an “online tool” or an express grant of authority in

the user’s estate planning documents or power of attorney. Hence,

RUFADAA respects the concept of “lawful consent” under the SCA, and,

unlike UFADAA, does not attempt to impute such lawful consent to the

fiduciary.

213

As of December 3, 2023, RUFADAA has been enacted in forty-five

states, the District of Columbia, and the United States Virgin Islands:

Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida,

Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine,

Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska,

Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North

Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South

Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia,

Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

214

207. Id.

208. Id.

209. Id. at 10–11.

210. Id. at 11.

211. Id.

212. Id.

213. Michael D. Walker, The New Uniform Digital Assets Law: Estate Planning and Administration

in the Information Age, 52 R

EAL PROP., TR. & EST. L. J. 51, 59 (2017).

214. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11.

26 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

California enacted the decedent’s estates and trusts provisions of

RUFADAA in 2016.

215

NCCUSL, however, does not consider this legislation

sufficiently complete to be treated as a RUFADAA enactment because it does

not cover powers of attorney or conservatorships where the principal or

conservatee is still alive.

216

As of December 3, 2023, RUFADAA was pending in Massachusetts.

217

A. Definitions

Section 2 of RUFADAA defines key terms, the most important of which

include:

1. Catalogue of Electronic Communication

The “catalogue” includes “information that identifies each person with

which a user has had an electronic communication, the time and date of the

communication, and the electronic address of the person.”

218

For emails, this

would include a list of when emails were sent or received and the email

addresses involved, but it would not include any of the text of the email or

the subject line.

219

2. Content of an Electronic Communication

The “content” includes “information concerning the substance or

meaning of the communication which: (A) has been sent or received by a

user; (B) is in electronic storage by a custodian . . . ; and (C) is not readily

accessible to the public.”

220

This would include the actual substance or text

of an electronic message that is not accessible to the public.

221

If the

electronic message was accessible by the public, it would not be subject to

the federal privacy protections under the SCA and would not be defined as

“content” pursuant to RUFADAA.

222

An example of an electronic

215. Id.

216. Id.

217. See id.; Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act, Revised, U

NIF. L. COMM’N, https://www.uniform

laws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=f7237fc4-74c2-4728-81c6-b39a91ecdf22 (last

visited Sept. 22, 2023) [https://perma.cc/P45T-E32K].

218. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2(4) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

219. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11; see R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS

ACT § 2(4) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

220. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2(6) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

221. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11; see R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS

ACT § 2(6) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

222. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11; see R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS

ACT § 2(6) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

2023] ESTATE PLANNING FOR CYBER PROPERTY 27

communication that would not fall under this definition is a “tweet” by a X

user that is accessible to the general public.

223

3. Digital Asset

A “digital asset” is defined in RUFADAA as “an electronic record in

which an individual has a right or interest.”

224

A digital asset “does not

include an underlying asset or liability unless the asset or liability is itself an

electronic record.”

225

“Electronic” means “relating to technology having

electrical, digital, magnetic, wireless, optical, electromagnetic, or similar

capabilities,” and “record” means “information that is inscribed on a tangible

medium or that is stored in an electronic or other medium and is retrievable

in perceivable form.”

226

The term “digital asset” is very broad and encompasses all electronically

stored information, including (a) information stored on a user’s computer and

other digital devices, (b) content uploaded onto websites, (c) rights in digital

property, and (d) records that are either the catalogue or the content of an

electronic communication.

227

4. Online Tool

An “online tool” is “an electronic service provided by a custodian that

allows the user, in an agreement distinct from the TOSA between the

custodian and user, to provide directions for disclosure or nondisclosure of

digital assets to a third person.”

228

This “third person” is referred to as the

“designated recipient” in RUFADAA to clarify that such a named person is

not required to be the fiduciary and is not to be held to the same legal standard

of conduct as a fiduciary.

229

223. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 11–12; see REVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS

ACT § 2(6) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

224. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2(10) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

225. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2(10) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

226. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2(11), (22) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

227. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2 cmt. (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

228. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2 (16) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

229. Beyer & Nipp, supra note 1, at 12; R

EVISED UNIF. FIDUCIARY ACCESS TO DIGIT. ASSETS ACT

§ 2 cmt. (UNIF. L. COMM’N 2015).

28 ESTATE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 16:1

As of December 2023, not many service providers offer an online

tool.

230

The only three major providers with online tools are Facebook,

Google, and Apple.

231

Google created its Inactive Account Manager in April 2013, long before

any other service provider and long before the promulgation of

RUFADAA.

232

The Inactive Account Manager allows users to control what

happens to emails, photos, and other documents stored on Google sites such

as +1s, Blogger, Contacts and Circles, Drive, Gmail, Google+ Profiles, Pages

and Streams, Picasa Web Albums, Google Voice, and YouTube.

233

The user

sets a period of time after which the user’s account is deemed inactive.

234

Once the period of time runs, Google will notify the individuals that the user

specified and, if the user so indicated, share data with these users.

235

Alternatively, the user can request that Google delete all contents of the

account.

236

Facebook, the world’s most popular online social network, recognized

a need to allow a deceased person’s wall to provide a source of comfort in

2009.

237

In its earliest stages, Facebook’s deceased user policy allowed for

two solutions upon the death of a user: (1) memorialize the account or

(2) delete the account.

238

More options are currently available.

239

The most recent addition to Facebook’s deceased user policy is a true

online tool to designate a “Legacy Contact,” that is, a person designated by a

user to delete the account or look after the user’s account if it is

memorialized.

240

The actions a Legacy Contact can and cannot take are

detailed on Facebook’s website.

241

Apple has also recognized the need to allow access to a deceased

person’s account post-death.

242

Newer Apple iOS versions allow for the

implementation of Legacy Contacts, allowing someone access to your stored

data upon your death.

243