10.3

million jobs in 2017

Renewable Energy and Jobs

Annual Review 2018

2

KEY FACTS

Annual Review 2018

10.3

million

jobs in 2017

5.3 % growth

43

% of all RE

jobs are

in China

3.4

million

jobs are in

the solar

industry

1.5

x job growth

from 2012

(excl. large hydro)

Key Numbers

3

R

Global renewable energy employment reached 10.3 million jobs in 2017,

an increase of 5.3% compared with the number reported in the previous

year.

R

An increasing number of countries derive socio-economic benets from

renewable energy, but employment remains highly concentrated in a

handful of countries, with China, Brazil, the United States, India, Germany

and Japan in the lead.

R

China alone accounts for 43% of all renewable energy jobs. Its share

is particularly high in solar heating and cooling (83%) and in the solar

photovoltaic (PV) sector (66%), and less so in wind power (44%).

R

The PV industry was the largest employer (almost 3.4 million jobs, up 9%

from 2016). Expansion took place in China and India, while the United

States, Japan and the European Union lost jobs.

R

Biofuels employment (at close to 2 million jobs) expanded by 12%, as

production of ethanol and biodiesel expanded in most of the major

producers. Brazil, the United States, the European Union and Southeast

Asian countries were among the largest employers.

R

Employment in wind power (1.1 million jobs) and in solar heating and

cooling (807 000 jobs) declined as the pace of new capacity additions

slowed.

R

Large hydropower employed 1.5 million people directly, of whom 63%

worked in operation and maintenance. Key job markets were China, India

and Brazil, followed by the Russian Federation, Pakistan, Indonesia, Iran

and Viet Nam.

R

Employment remains limited in Africa, but the potential for off-grid jobs is

high, particularly as energy access improves and domestic supply chain

capacities are developed.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

4

Annual Review 2018

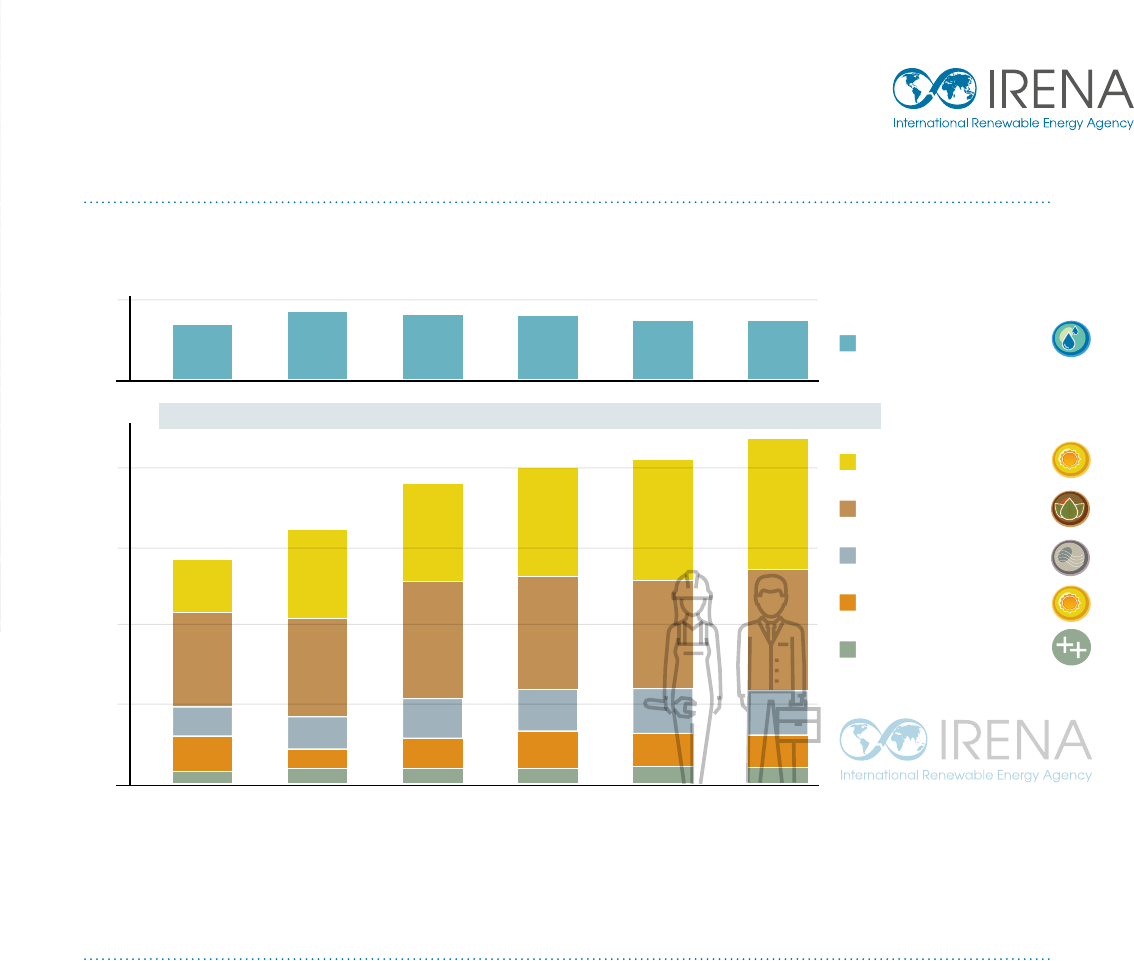

The renewable energy sector, including large

hydropower, employed 10.3 million people, directly and

indirectly, in 2017

1

. This represents an increase of 5.3%

over the number reported the previous year.

Renewable energy employment worldwide has

continued to grow since IRENA’s first annual assessment

in 2012. During 2017, the strongest expansion took place

in the solar photovoltaic (PV) and bioenergy industries.

In contrast, jobs in wind energy and in solar heating

and cooling declined, while those in the remaining

technologies were relatively stable (Figure 1).

1 Data are principally for 2016-17, with dates varying by country and techno-

logy, including some instances where only earlier information is available.

The data for large hydropower include direct employment only.

RENEWABLE

ENERGY

AND JOBS

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

5

Employment trends and patterns are shaped by a wide

range of technical, economic and policy-driven factors.

The falling costs of renewable energy technologies

continue to spur the deployment of renewables, and

during 2017, total investments edged up over 2016.

Job creation dynamics are subject to geographic

shifts in the production and installation of renewable

energy equipment. Corporate strategies and industry

realignments are important factors in this context, as

portions of the supply chain become more globalised

and geographically dierentiated.

Governmental policy, including the degree of

commitment to transforming the energy sector, is

also a key factor (IRENA, IEA and REN21, 2018). Policy

encompasses mandates, regulations and market design

in support of deployment, as well as industrial policies

to create and strengthen domestic value creation.

Where policies become less favourable to renewable

energy, change abruptly or invite uncertainty, the result

can be job losses or lack of new job creation. On the other

hand, expectations of adverse policy changes can lead

project developers to push forward a portfolio of projects

that would otherwise be initiated later, in order to beat a

certain cut-o date. The result in such cases is a temporary

surge of activity and employment creation, followed by

a drop. In the United States, for instance, the expected

imposition of taris on solar PV panel imports led to larger

deployments in 2016 but a slower pace during 2017.

Labour productivity has grown in importance as

renewable energy technologies have matured,

processes have been automated, and economies of

scale and learning eects have risen. As previous

editions of this Review have pointed out, bioenergy

feedstock harvesting is subject to growing

mechanisation in some countries. Automation of solar

PV panel manufacturing is already well advanced.

FIGURE 1: GLOBAL RENEWABLE ENERGY EMPLOYMENT BY TECHNOLOGY, 2012-17

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: The numbers shown in this Figure reflect those reported in past editions of the Annual Review.

a Includes liquid biofuels, solid biomass and biogas

b Other technologies include geothermal energy, hydropower (small), concentrated solar power (CSP), heat pumps (ground-based),

municipal and industrial waste, and ocean energy.

1.36

2.40

0.75

0.89

0.33

1.41

2.27

2.50

0.83

0.50

0.38

1.74

2.50

2.99

1.03

0.76

0.40

1.66

2.77

2.88

1.08

0.94

0.40

1.63

3.09

2.74

1.16

0.83

0.45

1.52

3.37

3.06

1.15

0.81

0.45

1.51

7.14

8.23

9.33

9.71

9.79

10.3

Large Hydropower

Others

a

Solar Heating / Cooling

Wind Energy

Bioenergy

b

Solar Photovoltaic

1.36

2.40

0.75

0.89

0.33

1.41

2.27

2.50

0.83

0.50

0.38

1.74

2.50

2.99

1.03

0.76

0.40

1.66

2.77

2.88

1.08

0.94

0.40

1.63

3.09

2.74

1.16

0.83

0.45

1.52

3.37

3.06

1.15

0.81

0.45

1.51

7.14 8.23

9.33

9.71 9.79 10.34

5.7

6.5 7.7 8.1 8.3 8.8

Large Hydropower

Solar Photovoltaic

Bioenergy

a

Wind Energy

Solar Heating / Cooling

Others

b

Total

Subtotal

1.36

2.40

0.75

0.89

0.33

1.41

2.27

2.50

0.83

0.50

0.38

1.74

2.50

2.99

1.03

0.76

0.40

1.66

2.77

2.88

1.08

0.94

0.40

1.63

3.09

2.74

1.16

0.83

0.45

1.52

3.37

3.06

1.15

0.81

0.45

1.51

7.14

8.23

9.33

9.71

9.79

10.3

Solar Photovoltaic

Bioenergy

b

Wind Energy

Solar Heating / Cooling

Others

a

Large Hydropower

201720162015201420132012

10

8

6

4

2

0

Million jobs

201720162015201420132012

8

6

4

2

0

2

0

Million jobs

201720162015201420132012

10

8

6

4

2

0

Million jobs

8

8

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

5000 1 000 1 500 2 000 2 500 3 000 3 500

Jobs (thousands)

Solar

Photovoltaic

Liquid Biofuels

Hydropower

(Large)

Wind Energy

Solar Heating/

Cooling

Solid Biomass

Biogas

Hydropower

(Small)

Geothermal

Energy

CSP

Municipal and

industrial waste

Tide, Wave and

Ocean Energy

Others

1 931

1 514

93

34

28

1

8

1 148

3

365

807

780

344

290

10.3

million jobs in 2017

6

This fifth edition of Renewable Energy and Jobs –

Annual Review provides the latest available estimates

and calculations on renewable employment. It

represents an ongoing eort to refine the data,

including IRENA’s own methodology. Global numbers

are based on a wide range of studies with varying

methodologies and uneven detail and quality

2

.

The first section highlights employment trends by

technology (Figure 2). It discusses employment in solar

PV, liquid biofuels, wind, solar heating and cooling, and

large hydropower (Box 1). For other technologies which

employ far fewer people, less information is available.

The second section oers insights for selected

countries. In addition, gender aspects (Box 2) and o-

grid developments (Box 3) are discussed.

FIGURE 2: RENEWABLE ENERGY EMPLOYMENT BY TECHNOLOGY

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: Others includes jobs which are not technology specific.

2 Prominent methodologies include input-output modelling, industry surveys and employment-factor calculations, with varying degrees of detail and sophisti-

cation. For the most part, the employment numbers in this report cover direct and indirect (supply chain) jobs. The data for large hydropower include direct

employment only.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

Japan

China

United States

India

2.3

2.2

2.1

2.0

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Million jobs

China

2.4

2.2

2.0

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Bangladesh

Malaysia

Germany

Philippines

Turkey

Chinese Taipei

South Africa

United

Kingdom

Mexico

Italy

Japan

United States

of America

India

Million jobs

Bangladesh

Malaysia

Germany

Philippines

Turkey

Chinese Taipei

South Africa

United

Kingdom

Mexico

Italy

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

3.4

65%

65%

of PV

jobs

million

3.4

million

7

RENEWABLE

ENERGY

EMPLOYMENT BY

TECHNOLOGY

SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAICS

Globally, the solar PV industry had another banner

year, with record installations of 94 gigawatts (GW)

during 2017, up from 73 GW in 2016, and significant new

job creation. China, India, the United States and Japan

were the most important markets, followed by Turkey,

Germany, Australia and the Republic of Korea (IRENA,

2018b). Employment increased by 8.7% to approach

3.37 million jobs in 2017

3

.

A key feature of the solar PV landscape is that jobs

remain highly concentrated in a small number of

countries. This can be attributed to the fact that the bulk

of manufacturing takes place in relatively few countries

and domestic markets vary enormously in size. The top

five countries, led by China, account for 90% of solar

PV jobs worldwide. Of the leaders shown in Figure 3,

eight are Asian. Overall, Asia is home to almost 3 million

solar PV jobs. This represents 88% of the global total,

followed by North America’s 7% share and Europe’s 3%.

3 The countries for which IRENA’s database has solar PV employment estimates represent 387 GW of cumulative installations, or 99% of the global total. They also

represent the same share of the 94 GW of new installations in 2017.

FIGURE 3: LEADERS IN SOLAR PV EMPLOYMENT

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: The threshold for inclusion in the figure is 10 000 jobs.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

8

Reflecting its unchallenged status as the leading

producer of PV equipment and the world’s largest

installation market, China accounted for about two-

thirds of PV employment worldwide, or some 2.2

million jobs. Job gains were once again strongest in the

installations segment, which now accounts for 36% of

China’s PV jobs (CNREC, 2018). Likewise, strong growth

in new capacity additions boosted employment in India

to an estimated 164 000 jobs.

By contrast, European PV employment continued its

downward slide, reflecting limited domestic installation

markets and a lack of competitiveness among European

module manufacturers. Revised estimates indicate

an 8% decrease to 99 600 jobs across the European

Union in 2016

4

(EurObserv’ER, 2018). More surprisingly,

US employment fell as well, for the first time, to about

233 000 jobs

5

(Solar Foundation, 2018). Japan’s slowing

pace caused employment to fall from 302 000 in 2016

to an estimated 272 000 jobs in 2017.

As deployment of solar PV continues to expand, more

and more countries will benefit from job creation

along the supply chain, primarily in installations and

operations and maintenance (O&M) (IRENA, 2017b).

LIQUID BIOFUELS

With the exception of Brazil, all major bioethanol

producers were estimated to have reached new

output peaks in 2017. Biodiesel production also rose

in many of these countries, but remained somewhat

below previous levels in Argentina, Indonesia and

the Philippines, and at much lower levels in China

6

.

Worldwide employment in biofuels is estimated at

1.93 million, a change of 12%. Most of these jobs are

generated in the agricultural value chain (in planting

and harvesting of feedstock).

The construction of fuel-processing facilities and O&M

of existing plants employ fewer people, but typically

require higher skills and oer better pay.

It should be noted that changes in biofuels employment

do not necessarily equate to net job gains or losses. Oil

palm, soybean and similar types of feedstock are used

for a range of agricultural and commercial purposes in

addition to the energy sector, and the composition of

end-use demand is relatively fluid.

The regional profile of biofuels employment diers

considerably from that of the solar PV sector. Latin

America accounts for half the jobs worldwide, whereas

Asia (principally labour-intensive Southeast Asian

feedstock supply activities) accounts for 21%, North

America for 16% and Europe for 10%. Figure 4 includes

the dozen countries with at least 10 000 jobs and shows

that the top 5 alone account for about 80% of global

estimated employment.

4 The jobs data for the European Union and its member states throughout this report are for 2016, the most recent year for which such information is available.

Details are at the EurObserv’ER website, https://www.eurobserv-er.org/17th-annual-overview-barometer/.

5 The Solar Foundation carries out an annual survey of employment across all solar technologies, but does not offer a breakout for solar PV jobs. The figure

reported here is an IRENA estimate.

6 The 2017 production estimates are derived from the national biofuels reports published by the US Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agriculture Service,

available at https://www.fas.usda.gov/commodities/biofuels.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

United States

of America

Colombia

Indonesia

Thailand

Malaysia

China

India

Poland

France

Germany

Romania

Brazil

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Million jobs

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1.9

million

41%

Brazil

United States

Colombia

0.8

0.7

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Million jobs

Indonesia

Thailand

Malaysia

China

India

Poland

France

Germany

Romania

1.9

million

41%

of biofuel

jobs

9

Brazil continued to have the largest liquid biofuel

workforce. The estimated 795 000 jobs indicate a small

increase from the previous year. Employment also rose

in the United States, buoyed by record production

of ethanol and biodiesel (Urbanchuk, 2018). Biofuel

output and employment also expanded in the European

Union, which had an estimated 200 000 jobs in 2016

(EurObserv’ER, 2018).

Indonesia’s biofuels production has experienced a

roller-coaster in recent years, impacted by changing

export demand. Production in 2017 fell again, though

not as dramatically as in 2015 (USDA-FAS, 2017a).

Based on its employment-factor approach, IRENA

estimates that close to 180 000 people worked in

Indonesia’s biodiesel sector in 2017, a 22% decline from

the previous year

7

. Biofuel output reached new peaks

during 2017 in Malaysia and Thailand. IRENA estimates

that these two countries together employed some

133 000 people, with most of the jobs in feedstock

supply

8

.

Colombia is another important and labour-intensive

Latin American biofuel producer. Its output in 2017

rose to a high of about 1 billion litres in 2017 (USDA-

FAS, 2017b). Estimates based on data published by

Federación Nacional de Biocombustibles de Colombia

(FNBC, n.d.) suggest the number could have been as

high as 190 800 jobs in 2017, but it is unclear whether

these represent full-time equivalents.

FIGURE 4: LEADERS IN LIQUID BIOFUELS EMPLOYMENT

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: The threshold for inclusion in the figure is 20 000 jobs.

7 The calculation relies on revisions of an employment factor initially developed by APEC (2010). This factor is applied as a constant each year for smallholder

production, which accounts for 45% of volume (WWF, 2012) and is more labour intensive than large-scale plantations. For plantations, IRENA applies an

assumed “decline” factor of 3% per year as a proxy for rising labour productivity.

8 In Thailand, IRENA estimates 102 600 jobs. Smallholders have a 73% production share, an average of values reported by Termmahawong (2014) and by RSPO

(2015). In Malaysia, smallholders account for 35% of production (WWF, 2012). IRENA estimates 29 700 jobs in Malaysia. In addition, IRENA estimates 35 400

jobs in the Philippines.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

China

Germany

United States

0.55

0.50

0.45

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0

Million jobs

India

United Kingdom

Brazil

Denmark

Netherlands

France

Mexico

Spain

Philippines

Turkey

Poland

Canada

South Africa

Germany

United States

of America

India

United Kingdom

Brazil

Denmark

Netherlands

France

Mexico

Spain

Philippines

Turkey

Poland

Canada

South Africa

China

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Million jobs

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0

3.4

44%

million

1.1

million

44%

of wind

jobs

10

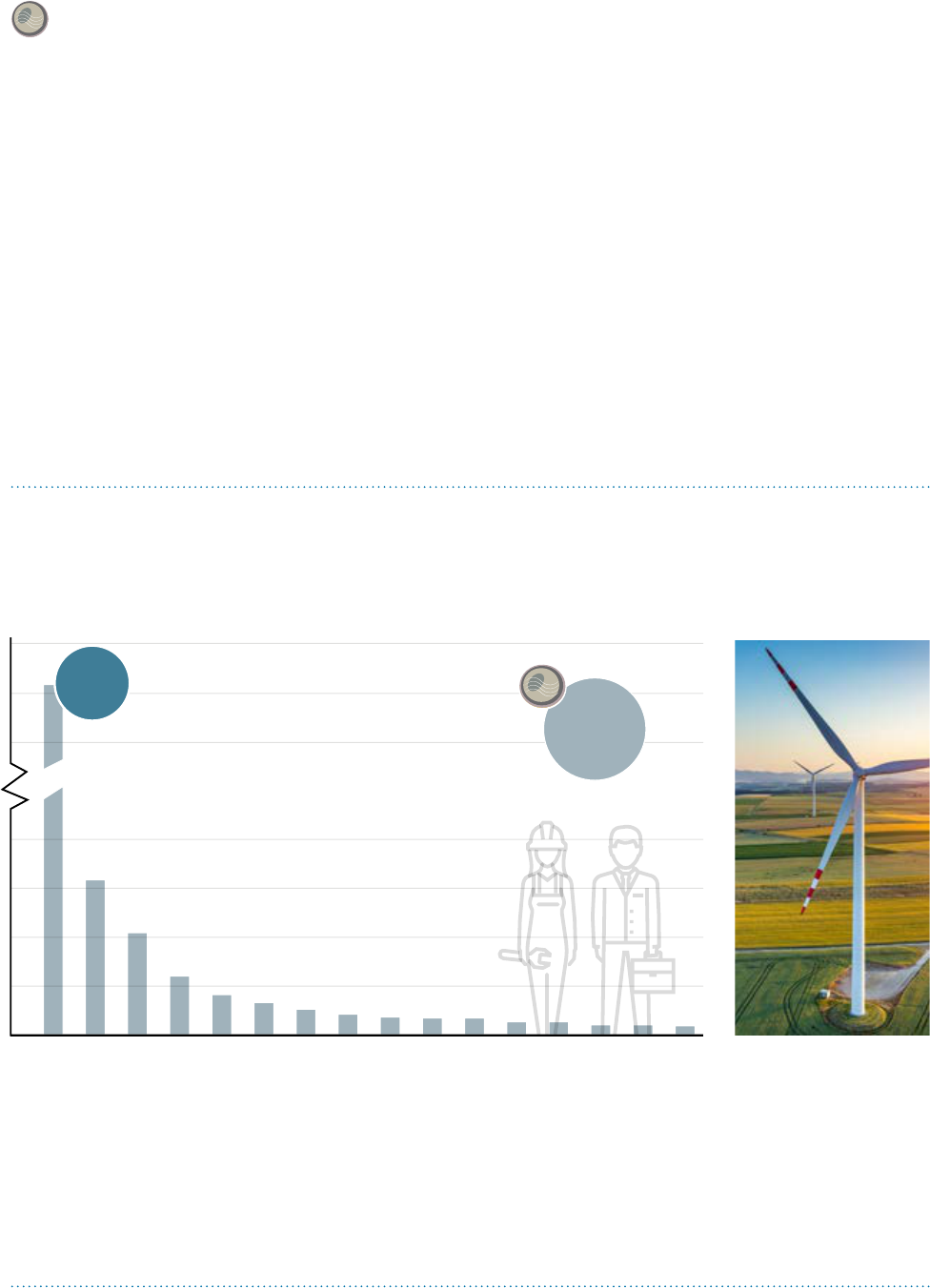

WIND

Including its onshore and oshore segments, the wind

industry employs 1.15 million people worldwide, a

0.6% decrease from 2016

9

. Most wind jobs are found

in a small number of countries, although the degree of

concentration is lower than in the solar PV sector. China

alone accounts for 44% of global wind employment.

The top five countries represent 76% of the total. The

regional picture is also somewhat more balanced than

in the solar PV industry. Asia’s 610 000 wind jobs make

up about half the total, while Europe accounts for 30%

and North America 10%. Of the top 16 countries shown

in Figure 5, seven are European, four are Asian

10

, three

are from North America and one each is from Africa

and South America.

China retained its undisputed lead in both new and

cumulative installations during 2017. While new wind

installations decreased 15%, those in the job-intensive

oshore sector increased by 26%. The country’s

total wind employment remained steady at 510 000

jobs (CNREC, 2018). Following China, five countries –

Germany, the United States, India, the United Kingdom,

and Brazil – together accounted for another 50% of

global installations.

Wind employment in the United States edged up by

3% to a new high of 105 500 jobs in 2017 (AWEA, 2018).

Brazil’s pace of installations remained roughly at the

level of 2015, with employment estimated at 33 700 jobs.

9 The countries for which IRENA’s database has wind power employment estimates represent 511 GW of cumulative installations, or 99% of the global total.

They also cover the same share of the 46 GW of new installations in 2017.

10 For the purposes of this report, Turkey is counted as part of Asia.

FIGURE 5: LEADERS IN WIND EMPLOYMENT

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: The threshold for inclusion in the figure is 10 000 jobs.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

11

Employment in Europe’s wind sector reached 344 000

jobs in 2016 (the year with the latest available data),

representing a 10% increase over 2015. New wind

installations amounted to 15.6 GW during 2017, up

25% from 2016. Some 12.5 GW added onshore and

3.2 GW oshore brought the continent’s cumulative

total to 168.7 GW (Wind Europe, 2018b). Europe’s wind

industry is a global technology leader, especially in

the oshore segment, where it accounts for 88% of

installed capacity worldwide.

Export markets hold considerable importance for sales

and jobs; some European sites produce exclusively for

export (Deloitte and Wind Europe, 2017).

11

Competition among manufacturers and service

providers is intensifying internationally; requirements in

some countries to source a certain share of equipment,

components and services locally are reshaping the

industry; and the supply chain is becoming more

globalised. More than 80% of European wind firms have

either a manufacturing or commercial presence in other

parts of the world (Deloitte and Wind Europe, 2017). As

a recent example, Danish turbine manufacturer Vestas

announced in early 2018 plans to build a hub and

nacelle assembly facility in Argentina, where it has sold

its products since 1991 (Weston, 2018).

With a diversifying global supply chain, employment will

be created in growing numbers of countries. IRENA’s

work has documented the opportunity to create jobs

along the supply chain (IRENA, 2017c, 2018c).

SOLAR HEATING AND COOLING

The available information for 2017 shows a decline in

major solar heating and cooling markets including

China, Brazil and India (Epp, 2018). IRENA estimates

that global employment in the sector stood at

807 000 jobs in 2017, a 2.6% decrease from the previous

estimate.

Estimates for China suggest that employment declined

from the previous year (CNREC, 2018). The country

has long been the clear leader in deployment of solar

heating and cooling, and still accounts for 83% of total

jobs in the sector. The top five countries account for

94% of all jobs. Of the top 10, four countries each are

from Asia and Europe.

Employment in the European Union is thought to have

declined slightly in 2016 (the most recent year with

available data), to 34 300 jobs

12

. The Brazilian market

declined for a second year in a row, by 3% in 2017

(ABRASOL, 2018). IRENA’s employment-factor-based

estimates

13

suggest that the country’s employment in

this sector fell slightly, to about 42 400 jobs. Turkey

has an estimated 16 600 people working in this sector

(Akata, 2018). In the United States, employment was

estimated by IRENA at 12 500 jobs in 2017. For India,

where annual installations have fluctuated in recent

years, the employment-factor calculation suggests that

the country may have had some 17 240 jobs in 2017,

when 1.5 million square metres of collector area was

added (Epp, 2018).

11 This is the case, for instance, at Enercon’s Viana do Costelo manufacturing cluster in Portugal (tower, blades and generators), and at Vestas’ Daimiel blade

factory in Spain. In Portugal, the site provides employment for 2 500 people directly and indirectly; the Spanish factory employs 1 000 people directly (Deloitte

and Wind Europe, 2017).

12 Eurobserv’ER (2018) reports a combined 29 000 jobs for solar heating and cooling and concentrating solar power but national-level reports suggest a higher

figure of 39 900. Of these, there are some 5 600 CSP jobs in Spain and Germany. On the basis of these numbers, the solar heating and cooling employment

is estimated at 34 300 jobs.

13 IRENA uses an employment factor of one full-time job per 87 square metres installed, as suggested by IEA SHCP (2016).

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

20172016201520142013

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

Million jobs

Viet Nam

Iran

Indonesia

Pakistan

Russian

Federation

Brazil

India

China

Rest of the World

Rest of

the World

Large

Hydropower

Brazil

China

Russian

Federation

31%

1.66

1.65

1.71

1.58

1.51

21%

19%

12%

Viet Nam

3%

4%

India

3%

Iran

Indonesia

3%

Pakistan

4%

12

BOX 1. EMPLOYMENT IN LARGE HYDROPOWER

Information on employment in the hydropower sector

remains sparse. For the fourth year in a row, IRENA

estimates the number of jobs in large hydropower

through an employment-factor approach that allows

an examination of direct jobs in the dierent segments

of the value chain (manufacturing; construction and

installation; and O&M).

This year’s calculations indicate approximately

1.5 million direct jobs in 2017, a decline of 10% from

the previous year. The drop was primarily driven

by developments in China and Brazil, where new

installations in 2017 levelled o from the earlier rapid

pace of capacity additions. The key job markets in

the sector are China, India and Brazil, which together

account for 52% of total direct employment (Figure 6).

China’s share of large-hydropower employment

declined by 20% in 2017 because of rising labour

productivity and a drop in new installations. India’s

FIGURE 6: EVOLUTION OF LARGE HYDROPOWER EMPLOYMENT BY COUNTRY

Source: IRENA jobs database.

HYDROPOWER

As described in previous editions of this publication,

estimating employment in hydropower is quite

challenging, as data remain surprisingly scarce and

it is dicult to clearly distinguish small from large

hydropower jobs. Small hydropower is estimated

to have employed 290 000 people in 2017. Large

hydropower employed about 1.5 million people directly

in 2017, with the majority in the O&M segment of the

value chain (Box 1). The global estimates for 2013-

17 have been updated following a major revision of

employment factors, statistics and available data

from countries. Temporal and geographic variations in

labour productivity were also reviewed.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

20172016201520142013

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

Million jobs

Viet Nam

Iran

Indonesia

Pakistan

Russian

Federation

Brazil

India

China

Rest of the World

Rest of

the World

Large

Hydropower

Brazil

China

Russian

Federation

31%

1.66

1.65

1.71

1.58

1.51

21%

19%

12%

Viet Nam

3%

4%

India

3%

Iran

Indonesia

3%

Pakistan

4%

13

labour-intensive hydropower sector accounted for

19% of the jobs, followed by Brazil (12%), the Russian

Federation (4%) and Pakistan (4%). Other relevant

employers include Indonesia, Iran and Viet Nam (3%

each) (Figure 7).

The results provide interesting insights into segments

of the renewable energy value chain. Given the large

cumulative capacities installed, 63% of the direct jobs in

the global large hydropower sector are found in O&M. In

fact, O&M employs more than 932 000 people to service

the 1 terawatt of installed capacity worldwide. The share

of jobs in construction and installation decreased from

38% in 2016 to 30% in 2017, owing to a leaner project

pipeline. The manufacturing segment, because of its

lower labour intensity, remains a distant third.

FIGURE 7: EMPLOYMENT IN LARGE HYDROPOWER

BY COUNTRY IN 2017

Source: IRENA jobs database.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

14

RENEWABLE

ENERGY

EMPLOYMENT

IN SELECTED

COUNTRIES

The renewable energy sector employed 10.3 million

people, directly and indirectly, in 2017. Excluding

large hydropower, employment increased by 6.3%

to reach 8.8 million in 2017. As in previous years, the

leading renewable energy job markets were China,

Brazil, the United States, India, Japan and Germany

(Figure 8). This section presents key country-level

trends. Jobs in the hydropower sector have not been

included in this analysis because job estimates for large

facilities include only direct jobs (based on the IRENA

employment-factor approach), whereas data for most

other renewables include both direct and indirect jobs

(primarily based on data collection from primary and

secondary sources).

Overall, renewable energy employment continued to

shift towards Asian countries, which accounted for 60%

of jobs in 2017, compared with 51% in 2013. Most of Asia’s

dynamism is based on growing domestic deployment

and strong manufacturing capabilities, supported by

policies such as feed-in taris, auctions, preferential

credit and land policies, and local content rules.

FIGURE 8: RENEWABLE ENERGY EMPLOYMENT IN SELECTED COUNTRIES

Source: IRENA jobs database.

a Jobs in large hydropower are not included in the country totals given differences in methodology

and uncertainties in underlying data. However, data for the EU and Germany include large hydropower jobs.

1 268

432

283

16

16

44

893

786

3 880

China

North

Africa

Rest of

Africa

South Africa

Jobs (thousands)

EU

India

Japan

Brazil

United States

of America

Germany

332

1,246

432

283

16

16

44

893

786

3,880

China

North

Africa

Rest of

Africa

South Africa

Jobs (thousands)

EU

India

Japan

Brazil

United States

of America

Germany

332

million

jobs

in 2017

in large

hydropower

in 2017

million jobs

8.8

+

1.5

a

1 246

432

283

16

16

44

893

786

3 880

China

North

Africa

Rest of

Africa

South Africa

Jobs (thousands)

EU

India

Japan

Brazil

United States

of America

Germany

332

8.8

million jobs in 2017

in large

hydropower

in 2017

million jobs

+

1.5

a

8.8

million jobs in 2017

in large hydropower

million jobs

in 2017

+

1.5

a

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

15

As in past years, China continued to have

the largest number of people employed,

accounting for 43% of the world’s total. The number

climbed from 3.6 million jobs in 2016 to 3.8 million in

2017, a growth of 5% (CNREC, 2018). This was entirely

due to the continued expansion of the solar PV sector.

Employment in solar water heating declined, and

remained essentially unchanged in other renewable

energy sectors. Solar PV employment was estimated

at 2.2 million jobs, an expansion of 13% over the

previous year. Of these jobs, almost 1.4 million were

in manufacturing. Following the record solar PV

installations in 2017, some 792 000 people were

working in the construction and installation segment,

25% more than in 2016.

Wind employment was estimated at 510 000 jobs

in 2017. The pace of new installations, at 15 GW, was

somewhat slower than in 2016. However, installations

in the job-intensive oshore wind energy sector rose

by 26%. Increased localisation of the value chain and

growth in exports ensured that employment in the

sector remained steady.

Employment in the Chinese solar water heating industry

continued its downward trend. After a 2.8% drop in

2017, employment in the sector stood at 670 000

jobs. The other renewable energy technologies weigh

less heavily: solid biomass at 180 000 jobs, biogas

at 145 000, small hydropower at 95 000, biofuels at

51 000 and concentrated solar power at 11 000. This

year’s estimates also include, for the first time, a figure

of 2 000 jobs in geothermal heat.

In Brazil, most renewables employment is

still in liquid biofuels and large hydropower.

Total biofuel employment rose by 1% in 2017 to 593

400 jobs. Ethanol jobs declined due to the steady

automation of feedstock supply and a decline of

ethanol production (USDA-FAS, 2017c)

14

.

While ethanol-related employment fell, it was more

than oset by gains in biodiesel jobs (ABIOVE, 2018).

IRENA estimates that Brazil employed 202 000 people

in biodiesel in 2017, up more than 30 000 from the

previous year

15

.

Brazil’s wind industry added about 2 GW in 2017,

about the same as during the preceding year (GWEC,

2018), to reach a cumulative 12.8 GW. Correspondingly,

IRENA’s employment-factor-based calculation yields

a wind power workforce of about 33 700 people in

nacelle and blade manufacturing; tower construction

and installation; and O&M

16

.

New installations in Brazil’s solar heating market declined

by 3% in 2017 (ABRASOL, 2018). Total employment in

2017 was estimated at about 42 000 jobs, with about

27 500 in manufacturing and 14 500 in installation

17

.

14 In 2016, Brazil had around 225 400 workers in sugarcane cultivation and 164 900 workers in ethanol processing (MTE/RAIS, 2018). A rough and dated estimate

suggests that there may be another 200 000 indirect jobs in equipment manufacturing.

15 Calculation based on employment factors for different feedstocks (Da Cunha et al., 2014). The shares of different feedstock raw materials are derived from

USDA-FAS (2017c). Soybean oil accounts for the bulk (about 71%), followed by beef tallow (16%) and cotton seed and vegetable oils (13%).

16 This calculation is based on employment factors published by Simas and Pacca (2014).

17 This IRENA calculation of installation jobs is based on Brazilian market data and a solar heating and cooling employment factor. The estimate for manufacturing

jobs is derived from an original 2013 estimate by Alencar (2013).

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

16

The United States experienced its first

job loss in the solar sector since 2010 when

the Solar Jobs Census (Solar Foundation, 2018) first

began tracking employment. The number of solar jobs

fell by 9 800 or 3.8%, to about 250 000

18

. Most of the

loss took place in the installation segment, aected by

a 22% reduction in new capacity additions, particularly

of utility-scale plants. The contrast between 2016 and

2017 is skewed by the fact that installations in 2016

were driven higher by expectations that a 30% federal

investment tax credit might expire. Policy uncertainties

in states such as California, Massachusetts and Nevada

also had an impact (Solar Foundation, 2018).

The installation segment of the value chain generates

more than half of all US solar jobs – 129 400 in 2017.

Manufacturing accounts for a fairly small 15% of

employment; more than 95% of solar panels are

imported (Swanson and Plumer, 2018). Project

development represents another 14% of jobs; sales

and distribution 12%; and the rest is in research and

development, government, and other activities.

The US solar industry is more gender diverse than its

fossil fuel industry. Women represented 27% of the

solar workforce. In general, women seem to hold a

higher share in total renewable energy jobs than in the

overall energy industry, about 20 to 25% (Box 2).

In January 2018, in response to a trade petition filed

by two manufacturers (Suniva and SolarWorld), the

US government imposed import taris for modules

and cells at a rate of 30%, set to decline to 15% over

four years. An initial analysis suggested that the taris

may reduce installations by 11% over the next five years

(Pyper, 2018). The Solar Energy Industries Association

(SEIA, 2018) forecasts a loss of up to 23 000 jobs in

2018, but the impact could be softened because the

first 2.5 GW of solar cells imported annually will be

exempted from taris (Eckhouse, 2018).

Previous trade duties imposed on Chinese solar products

in 2012 and 2014 failed to raise US solar manufacturing

(Roselund, 2016). In 2013, China imposed retaliatory

taris of 57% on imports of US polysilicon. As the US

share of world polysilicon production plummeted from

29% to 11% between 2010 and 2017 (while China’s share

rose to 70%), one-third of the US polysilicon workforce

was laid o (Foehringer Merchant, 2018; Roselund, 2018).

Employment in the US wind industry rose to about

105 500 jobs in 2017 (AWEA, 2018). The wind sector

continues to enjoy a period of stability made possible by

steady policies (notably the multiyear extension of the

production tax credit) and employment is now double

the level of 2013

19

. The number of manufacturing jobs

in 2017 is estimated at more than 23 000. This is down

slightly from 2016, but is oset by higher numbers in the

development, transportation and construction segment

of the supply chain. This reflects the fact that by year-end,

more than 13 GW of capacity were under construction

and 15 GW in advanced stages of development.

More than 80% of all US wind capacity is located in low-

income rural counties. Land lease payments totalling

USD 267 million in 2017 are helping to stimulate these

rural economies, in addition to tax revenues and income

earned from segments of the value chain (AWEA, 2018).

US ethanol production rose to a new record of about

60 billion litres in 2017, lifted by higher domestic

and export sales. Direct and indirect employment is

estimated at 237 000 jobs in 2017, a 6.5% increase

over 2016 (Urbanchuk, 2018). In the biodiesel sector,

production edged up slightly to about 6 billion litres in

2017 (EIA, 2018). IRENA’s employment-factor calculation

suggests a level of 62 200 jobs in 2017.

In 2016, the United States had a biomass power capacity

of about 16 GW in 2016 (EIA, 2017). An employment-

factor-based calculation suggests that direct and

indirect employment in biomass power might be close

to 80 000 jobs, roughly the same level of employment

as the previous year

20

.

18 This figure includes jobs in solar PV, solar heating and cooling, and concentrated solar power.

19 The production tax credit expired in 2013, leading to a drop in new investment to nearly zero and causing a temporary, but sharp, downturn in installations and

jobs before this support measure was renewed and extended by the US Congress.

20 This figure is based on an employment factor of 4 jobs per MW, applied to 16 GW of biomass power capacity, for some 64 400 jobs, and to 3.8 GW of

biomass-fired combined heat and power plants, for an additional 15 300 jobs.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

17

BOX 2. IRENA’S WORK ON GENDER

IRENA has strived to address the gender dimension in

its work on renewable energy employment. The 2013

report, Renewable Energy and Jobs (IRENA, 2013)

examined the role of women in renewable energy

development in both modern markets and energy

access contexts, and assessed the various constraints

faced by women in the sector.

Recognising a gap in gender-disaggregated data for the

renewable energy sector, IRENA has integrated surveys

as part of the Annual Reviews. The 2016 edition of the

Annual Review (IRENA, 2016a) reported that women

represented an average of 35% of the workforce of

nearly 90 companies responding to the online survey.

The 2017 edition (IRENA, 2017a) presented findings

of a survey conducted jointly by IRENA, the Clean

Energy Business Council and Bloomberg New Energy

Finance in the Middle East and North Africa region. It

found that gender discrimination in renewable energy

is less pronounced than in the energy sector at large.

Challenges to employment and promotion remain.

A variety of actions are needed, including flexibility

in workplace, mentorship and training, support for

parenting, fair and transparent processes, equal pay

and targets for diversity.

In 2018, IRENA will present new analysis of the gender

dimension of employment impacts among local rural

communities aected by large-scale renewable energy

project development. The study gathers primary data

from solar and wind projects being developed across

sub-Saharan Africa.

In the access context, IRENA has emphasised the

importance of integrating a gender perspective in

policy and programme design as a means to accelerate

adoption, enhance sustainability and maximise

benefits. The 2017 edition of the Annual Review

highlighted the benefits of cleaner cooking fuels,

such as biogas and improved cookstoves, for women.

As social entrepreneurs, women are also catalysts

for deployment as seen from several cases analysed

by IRENA such as the Wonder Women Initiative in

Indonesia (IRENA, 2016b, 2018d).

Globally, various initiatives have been launched to

focus attention on gender and energy. ENERGIA,

an international network focused on gender and

sustainable energy, has been playing a key role in

mainstreaming gender in energy policy making. The

challenge of expanding access to energy has elicited

women-centric eorts such as Barefoot College in India

and Solar Sister. In the United States, WRISE (Women

of Renewable Industries and Sustainable Energy) has

provided support to women in the wind sector for more

than a decade; it expanded its focus in 2017 to include

solar energy and a variety of related issues such as

energy storage, eciency and smart grids. The GWNET

(Global Women’s Network for the Energy Transition) has

been recently established with the aim of empowering

women in energy through interdisciplinary networking,

advocacy, training, coaching and mentoring, and

services related to projects and financing.

IRENA is committed to continue its work on the issue.

The agency has started work on a stand-alone report

on gender that will integrate up-to-date information

from around the world and present cutting-edge

thinking and insights on this topic.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

18

21 EurObserv’ER (2018) switched its methodology from a survey of industries to an input-output analysis, which allows for more consistent results for individual

EU member countries. The EU total, along with the other EU figures presented here, was adjusted by IRENA with national data in the cases of Austria (BNT,

2017), Germany (O’Sullivan et al., 2018), Spain (APPA, 2017) and the United Kingdom (REA, 2017).

In India new solar installations reached a

record 9.6 GW in 2017, eectively doubling

the total installed base of the technology in the country.

Employment in solar PV increased by 36% to reach

164 400 jobs, of which 92 400 were in on-grid

applications. IRENA estimates that the construction

and installation segment of the value chain accounts

for 46% of these jobs, with O&M and manufacturing

representing 35% and 19%, respectively.

Manufacturing of solar PV modules is limited, given the

availability of inexpensive imports, mostly from China. The

market share of domestic firms decreased from 13% in 2014-

15 to 7% in 2017-18. As of September 2017, the average price

for imported modules was USD 0.39 per Watt compared

with USD 1.44/W for domestic products and a large

share of the existing manufacturing capacity stands idle

(Sraisth, 2018).

India had the world’s fifth-largest additions to wind

capacity in 2017 at 4.1 GW and the fourth-largest

cumulative capacity (GWEC, 2018). IRENA estimates

that employment in the sector stood at 60 500.

In 2016, the most recent year for which

estimates are available, the number of jobs

in the European Union reached 1.19 million, up from

1.16 million in 2015. The numbers for both years reflect

a significant revision of estimates following adoption of

a new methodology (EurObserv’ER, 2018), and cannot

be directly compared with the results reported in

previous years

21

.

The European solid biomass and wind power industries

are providing the most jobs, at about 389 000 and

344 000, respectively. Both added jobs during 2016.

Biomass use is receiving growing policy support, but

half of Europe’s jobs in this sector are in just six countries:

Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Poland and Finland.

The wind industry remains one of the bright spots of

the European renewable energy sector. Half of the top

ten countries with the largest installed capacity in the

world are European. Germany, the United Kingdom,

France and Belgium were among the ten countries

worldwide that added the most new capacity in 2017

(GWEC, 2018).

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

19

22 Deloitte and Wind Europe (2017) provides a more conservative estimate of about 263 000 jobs. This is based on the number of jobs reported by each wind

energy company’s financial statement (direct jobs) and indices of productivity per MW installed and serviced (indirect jobs). This study estimates that manu-

facturing accounted for 53% of all direct jobs in 2016; services represented 27%, wind farm development contributed 15% and the remainder of jobs related to

the production and installation of offshore substructures.

23 Eurobserv’ER includes CSP in the solar thermal category.

24 EurObserv’ER includes the growing heat pump sector in its reporting on renewable energy employment and published an estimate of 249 400 jobs in 2016 for all

three types of equipment, ground source, hydrothermal and air source pumps. However, the largest segment by far, air source pumps, cannot unambiguously be

assumed to be renewable in character. Consequently, IRENA adjusted its own figure to the much smaller number reported. This is of particular consequence for

Italy, Spain and France.

25 Waste-to-energy technologies add another 7 700 jobs.

IRENA estimates the European Union’s wind power

employment in 2016 at close to 344 000.

22

Germany’s

160 000 jobs represented 47% of this total, followed

by the United Kingdom (41 800 jobs) whose onshore

market almost tripled in 2016. Denmark (26 600), the

Netherlands (21 500) and France (18 800) were next,

followed by Spain (18 000) (EurObserv’ER, 2018;

APPA, 2017; REA, 2017).

Oshore, European countries added a record 3.1 GW

of new wind capacity during 2017, double the pace

of 2016. The United Kingdom and Germany are the

global leaders in oshore wind, followed by Denmark

and the Netherlands (Wind Europe, 2017 and 2018a).

The Netherlands’ oshore capacity quadrupled in 2016

with close to 700 megawatts (MW) of capacity added,

doubling the country’s total wind jobs to an estimated

21 500 (EurObserv’ER, 2018).

The European Union’s biofuels sector employed about

200 000 people, up from 172 000 in 2015. The solar PV

industry continued to shrink in 2016, from 108 500 jobs

in 2015 to 99 600 in 2016. The solar thermal market

23

contracted by 4.6% in 2016, a reflection of low gas

prices and the lack of steady support policies. Poland’s

solar thermal market dropped by half, as did the

number of jobs. IRENA estimates employment in the

European Union’s geothermal sector at 25 000 jobs, of

which heat pumps accounted for 16 000 jobs

24

.

Renewable energy employment estimates

have also been revised for Germany. In

2016, the downward trend in evidence since 2011 came

to an end. At 325 000 jobs, the figure was slightly

higher than during the preceding year. The wind

industry was the largest renewables employer in 2016,

up 10 000 jobs. In fact, the 160 100 people working in

Germany’s wind sector equal the number of workers

in the next ten-largest European countries combined.

Most other renewable energy technologies added a

small number of jobs. However, solar PV employment

was down to about 35 800 jobs in 2016, from

38 100 in 2015 (O’Sullivan et al., 2018). The 1.53 GW and

1.75 GW of capacity newly installed in 2016 and 2017,

respectively, was less than a quarter of the 2012 peak

of 7.6 GW (BSW, 2016, 2018). It also falls short of the

government’s target of 2.5 GW (Enkhardt, 2018).

The United Kingdom ranks second in

Europe for its number of renewable energy

jobs. The Renewable Energy Association (REA, 2017)

puts total employment at 118 200 jobs for 2015/16

25

.

The largest sector is wind power, with 41 800 jobs.

Solar PV accounts for 13 700 jobs, while biofuels and

solid biomass each contribute about 10 000 jobs. Solar

heating and cooling is just below the 10 000 threshold.

France is Europe’s third-largest renew-

ables employer, with 107 000 jobs; solid

biomass and biofuels each employ more than 30 000

people. Poland, Spain and Italy were the fourth-, fifth-

and sixth-largest European employers.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

20

26 This figure excludes large hydropower but includes waste-to-energy technologies.

27 In the absence of direct employment data, this calculation is based on the assumption that employment closely tracks the 10% reduction in demand during 2017.

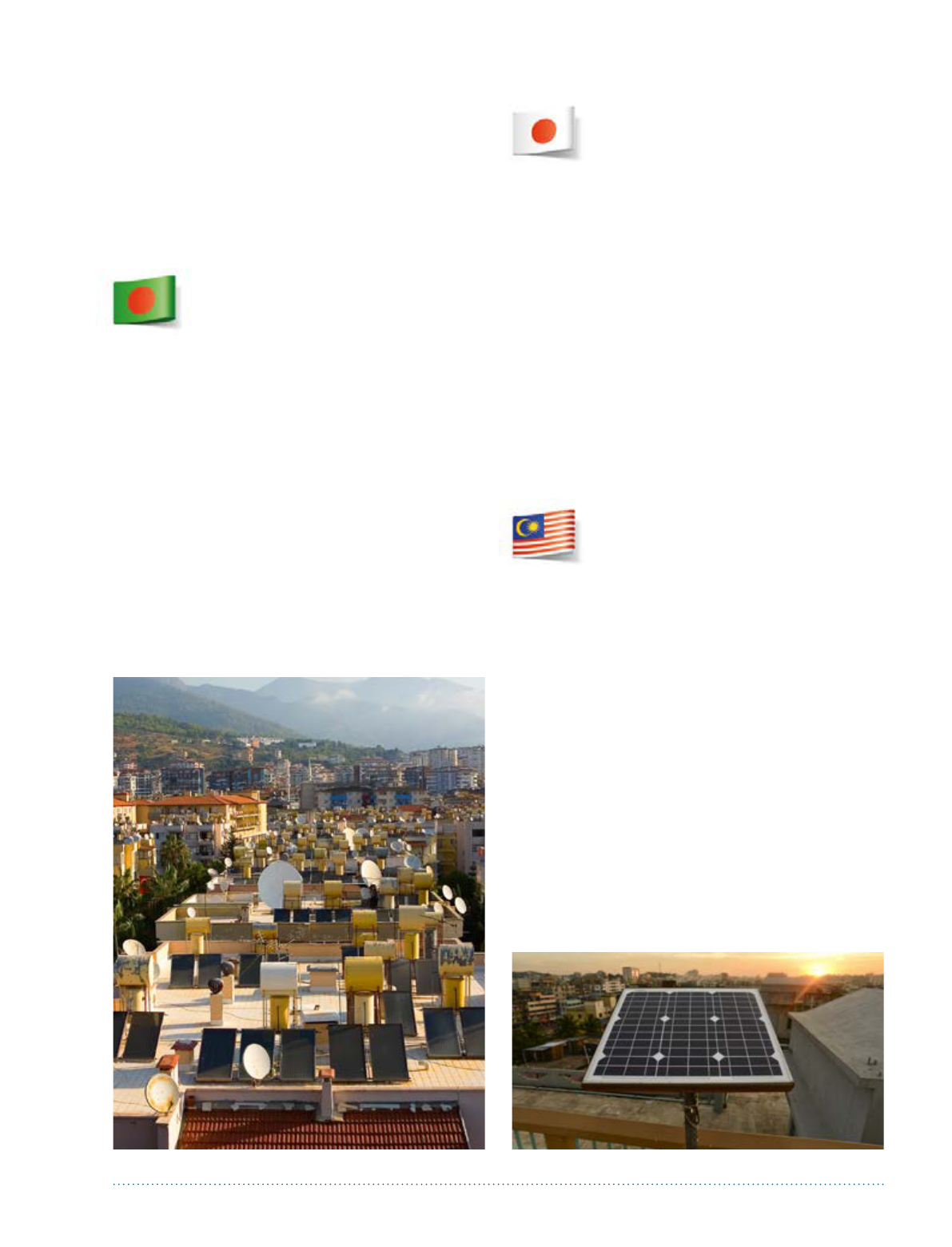

In a number of countries in various parts of Asia –

including Bangladesh, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines,

the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Turkey – most

renewable energy jobs are related to solar PV. In other

regions of the world, Australia, Mexico and South Africa

also report significant numbers of solar PV jobs.

Bangladesh’s solar home systems

programme has successfully deployed

more than 4 million systems in rural areas. However,

lack of coordination among government entities in rural

electrification has recently been causing diculties.

Following grid connection through Bangladesh’s

Rural Electrification Board, many households stopped

making instalment payments on their system. New

installations have reportedly fallen to an average of

2 000 a month from as high as 60 000 to 70 000

in earlier years. The Infrastructure Development

Company Limited’s (IDCOL’s) programme was also

weakened by the free distribution of solar panels under

the government’s TR-Kabikha project (The Asian Age,

2018). All of this has translated into reduced solar PV

employment, estimated by IRENA at 133 000 jobs.

Japanese demand for solar PV declined

by 10% in 2017, following a 23% decline in

2016. The most recent decline was the lingering result

of reductions in feed-in taris, land shortages and

limited grid access for new projects. Existing projects

already in the pipeline are being completed and few

new, large commercial and utility-scale projects are

being approved (Bermudez, 2018). According to a

private credit analysis firm, Tokyo Shoko Research

(TSR), there were 88 bankruptcies in Japan’s solar

industry during 2017, a sharp increase of 35% over

2016. According to TSR, 42 of the 88 companies cited

“poor sales” as the main cause for entering bankruptcy

proceedings (EnergyTrend, 2018). IRENA estimates

2017 employment at some 271 500 jobs, a reduction of

around 30 000 jobs from 2016

27

.

Malaysia’s domestic solar PV market is

quite small, but its PV manufacturing industry

is significant. Most of the facilities were set up as a result

of foreign direct investment by companies in China,

Japan, the Republic of Korea and the United States.

Supported by the Malaysian Investment Development

Authority, Malaysia has some 250 companies involved

in upstream activities such as polysilicon, wafer, cell and

module production, and also in components such as

inverters and system integrators (IEA-PVPS, 2017). The

country’s Sustainable Energy Development Authority

estimates that solar PV provides some 40 300 jobs. SEDA

(2018) puts biomass energy and biogas employment at

about 10 700 jobs, and small hydropower at more than

6 100 jobs. Further, IRENA’s employment-factor-based

calculation estimated close to 30 000 jobs in biodiesel

development, for a total of about 87 400 renewable

energy jobs.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

21

The Philippines reports having more

than 34 000 people working in the solar

PV industry, a number similar to the IRENA estimate of

the country’s biofuels employment if informal jobs in

the agricultural supply chain are included. In addition,

the Philippines has about 33 000 jobs in small hydro

and more than 14 000 in wind power (Neri, 2018).

The

Republic of Korea employs about

8 100 people in the manufacturing and

distribution of solar PV (Korea Energy Agency, 2018).

Singapore reports 4 300 PV jobs, up from

3 900 in 2015.

In Western Asia,

Turkey has seen its

solar PV sector expand with the help of

local content rules (Hirtenstein and Ant, 2016). New

installations in 2017 reached 2.6 GW, assisted by a year-

end installations rush before feed-in tari rates were

set to be reduced at the beginning of 2018 (Bhambhani,

2018). Turkey had 33 400 people working in the solar

PV sector and another 16 600 people in solar heating

and cooling in 2017. Wind power provided about

14 200 jobs and small hydro, geothermal power and

biogas accounted for another 18 000 jobs. Altogether,

the number of people working in renewable energy

thus totals about 84 000

26

(Akata, 2018).

Australia added 1.3 GW of utility-scale

solar PV capacity during 2017, a record. The

country is likely to install more than 3.5 GW during 2018.

It is estimated that this activity directly supported the

employment of about 4 400 people during 2017. Another

5 500 people were directly employed in the design, sale

and installation of roof-top solar systems. The wind

power sector accounts for 11 200 jobs (Green Energy

Markets, 2018), for a total of about 21 000. This uptick

comes after a number of years during which Australia’s

renewable energy employment had declined.

Mexico reports about 10 940 solar PV

and about 18 000 wind jobs, many of

them producing equipment for the neighbouring US

market. The country also has about 17 700 people in

the small hydro sector, 14 400 in solid biomass and

7 600 in geothermal power, for a combined total of

68 600 jobs (Vega, 2018).

Information on renewable energy employment on the

African continent remains limited.

According to government estimates,

Egypt has some 3 000 solar PV jobs.

In

Ghana, Africa’s largest solar PV project,

the 155 MW Nzema plant, was estimated to

have created 500 jobs during its 2-year construction,

and 200 permanent operations jobs. The facility was

likely to induce another 2 100 local jobs through sub-

contracting and demand for goods and services (Blue

Energy, 2015).

The largest level of employment on the

continent is found in

South Africa,

which, with the help of domestic content legislation,

has generated an estimated 15 000 jobs in solar PV

and close to 8 900 in the concentrated solar power

(CSP) industry. Wind power adds another 10 400 jobs.

Including much smaller employment in the small hydro

sector, the country has close to 35 000 renewable

energy sector jobs (Nxumalo, 2018).

Important developments are taking place in the o-

grid sector (Box 3).

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

22

BOX 3. OFF-GRID DEVELOPMENTS

New business models such as the “pay-as-you-go”

(PAYG) approach that is spreading in parts of Sub-

Saharan Africa are increasing the aordability of small

solar home systems for poorer rural households.

In the PAYG model, consumers use their phones to pay

a fixed up-front cost for a solar home system (typically

a small solar panel bundled with a battery, lights,

mobile phone chargers and possibly appliances), and

subsequently regular instalments until the cost of the

system is paid o.

These business models are supported in some

countries by the removal of import taris and

other taxes or fees on solar PV panels and other

components. As growing numbers of panels are sold,

employment is generated in segments of the supply

chain, especially in sales and distribution, installation

and O&M.

However, as long as there is only a limited domestic

capacity (or none at all) to assemble equipment or

manufacture components, economic multipliers and

the resulting employment and other benefits will

accrue elsewhere, and eorts to boost rural

development will remain limited. Indeed, the availability

of cheap imports acts as a powerful restraint against

the development of even a limited local industry. As

solar deployments scale up, the import bill rises as

well. Removing taris on imports of raw materials or

components needed to produce this equipment could

shift the economics and spur development of a local

industry. This could be further supported by policies

to certify qualified supplier firms, establish product

quality standards (to avoid the spread of poor-quality

products) and provide worker education and training

programmes (Mama, 2017).

In East Africa, M-KOPA and other start-ups have

been the main protagonists of the PAYG model. Until

recently, the company exclusively sold imported PV

panels. During 2016-17, however, M-KOPA reported

selling more than 100 000 solar PV panels that were

made in Kenya by Solinc East Africa. Cumulatively,

these panels have a generating capacity of close to

2 MW. In coming years, the company hopes to source

all its panels from Kenya – over the next two years,

this will amount to half a million panels representing

6.6 MW of power. The benefits include a shorter supply

chain and (facilitated also by government-required

product certifications [Mama, 2017]) a greater degree

of quality control.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

23

Starting operations in 2011, Solinc’s PV module factory

in Naivasha was the first such plant in East and

Central Africa, and currently serves markets in Kenya,

Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Majority

Kenyan-owned since 2015, it employs 130 Kenyans,

with plans to hire an additional 30 engineers over

the next two years to fulfill growing M-KOPA orders

(M-KOPA, 2018; Solinc East Africa, n.d.). The company

has weathered repeated changes in value-added tax

(VAT) and import duty regulations on solar products

and components during 2013-15 that aected pricing

and demand (Mulupi, 2016).

For all but the leading PAYG companies such as

M-KOPA, BBOXX, Fenix or d.light, a key challenge is

how to raise sucient capital to finance the upfront

cost of solar panels while households’ payments

are spread out over many instalments. A particular

diculty is that local financial institutions have been

reluctant to provide financing. The resulting reliance

on international investors has meant that the inherent

transaction costs and currency risks, along with profit

expectations, are translating into solar home system

prices in East Africa that cost twice as much as

comparable systems in Bangladesh, where a successful

microcredit model has led to the installation of more

than 4 million solar home systems (Sanyal et al., 2016).

Higher costs prevent greater uptake of decentralised

o-grid solutions and that in turn limits employment

opportunities.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC, 2018)

observes that since 2016, there has been a somewhat

greater prevalence of local currency financing, mostly

via agreements between the World Bank and Sub-

Saharan African countries. Further, in early 2018,

a potentially ground-breaking financing deal was

announced under which the o-grid solar company

BBOXX secured USD 4 million worth of debt financing

from the Union Togolaise de Banque (UTB), the first

such deal involving a local Sub-Saharan African bank.

In late 2017, BBOXX won a contract from the Togolese

government to provide 300 000 solar systems by

2022. The company aims to create more than 1 000

direct jobs in Togo over five years (Kenning, 2018).

Domestic sourcing of solar

panels and components

spurs rural development

and creates jobs.

Local currency nancing

can lower the cost of

renewables for households.

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

24

THE WAY

FORWARD

The role of renewables in the global energy system

keeps expanding. This process is key to stabilising the

global climate, avoiding environmental degradation,

and improving human health. As the global transition

towards a more sustainable energy system unfolds,

the world’s renewable energy workforce will continue

to expand. IRENA’s analysis suggests that jobs in the

sector could rise from 10.3 million in 2017 to 23.6 million

in 2030 and 28.8 million in 2050, in line with IRENA’s

more sustainable energy pathway (IRENA, 2018a).

A better understanding of employment along the value

chain helps decision makers formulate appropriate

policies to support the expansion of the renewable

energy sector. This entails not just deployment and

industrial policies, but also education and training of

new workers, eorts to retain skilled and experienced

employees (who demand attractive wages, good

working conditions and opportunities for career

advancement), and policies to ensure a just and fair

transition from the present energy system to one that

features renewables more strongly.

IRENA will continue to provide sound data and analysis

on the topic through further editions of this publication

and by contributing to the growing knowledge base on

the socio-economic benefits of renewables, including its

report series on Leveraging Local Capacities to analyse

skill requirements along the segments of the value chain

of dierent renewable energy technologies (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9. IRENA’S KNOWLEDGE BASE ON RENEWABLE ENERGY EMPLOYMENT

Renewable Energy and Jobs

December 2013

International Renewable Energy Agency

IRENA

IRENA woRkINg pApER

Renewable

Energy Jobs:

StAtUS, PROSPECtS & POlICIES

BIOfUElS AND gRID-CONNECtED

ElECtRICIty gENERAtION

Renewable Energy and Jobs

Annual Review 2014

MAY 2014

Renewable Energy

Jobs & Access

A SERIES OF CASE STUDIES

Burkina FasovBiomass

PROJECT PROFILE

FAFASO (“Foyers Améliorés au Faso” i.e., improved stoves in Burkina Faso) is a Dutch- German Energy Partner-

ship Energising Development (GIZ-EnDEV) project that commenced in 2006 and is sup ported by co-financing

from the Dutch Foreign Ministry (DGIS) and the German Ministry of International Cooperation (BMZ).

FAFASO covers all of Burkina Faso, with a focus on the biggest towns, Ouagadougou and Bobo Dioulasso, as well

as the South-western and Eastern regions. The project helps to disseminate improved cookstoves (ICS) that save

35–80% of wood or charcoal compared to the traditional three-stone-fire. In 2006–2011, about 180 000 ICS were

sold to households, institutions and productive units.

Most of the stoves disseminated are mobile, metal household stoves that are 35– 45% more ecient. For poorer

households, a mobile ceramic stove is also available and saves 40% fuel.

In addition, FAFASO oers big mobile metal stoves for restaurants and school canteens (saving around 60%) as

well as mud stoves for traditional beer brewing (saving about 80%).

The overall objective was to train ICS producers and help them sell the stoves commercially, so that dissemination

would continue even in the absence of subsidies.

The project entails marketing (large-scale eorts via TV and radio, small-scale cooking demonstrations, sal es

events, etc.), introduction of an ICS quality label, and eorts to strengthen the commercial supply chain.

JOBS AND TRAINING

Two thirds of the overall budget of USD 3.2 million (up to late 2011) has gone into training and marketing eort s;

fixed costs for project personnel, etc. account for one third.

A typical training s ession involves an average of 30 trainee s. By the end of 2010, FAFASO had trained a total

of 729 people — 285 metal smiths, 264 masons, and 180 potter s. The numbers expanded dramatically in 2009,

when the project began to train masons and potters. In 2010, when very few potters were trained, the numb ers

were smaller.

These numbers cannot be considered to constitute new jobs. Rather, the individuals concer ned are experienced

craftsmen. The training oers them higher qualification s and an opportunity for a sustained role fo r themselves

in the market. Many of the metal smiths and masons do employ apprentices.

Most of the potters are women in rural areas, whose main occupation remains work in the field and the household.

But they acquire knowledge that helps them generate additional income (and cope with competition from plastic

products). Pottery is caste-bound work dominated by certain families that are unlikely to employ apprentices.

As part of the training, all producers are taught to calculate the prices for the stoves, putting them in a better

position in markets.

SUPPLY CHAIN

Upstream Linkages

The stoves are produced domestically, in a decentralised, small-scale fashion. In general, the materials used

are indigenous. Previously imported scrap metal is now locally procured, but this does not necessarily indicate

increased demand and jobs.

June 2012

Renewable Energy

Jobs & Access

RENEWABLE

ENERGY

BENEFITS:

MEASURING THE

ECONOMICS

Renewable Energy and Jobs

Annual Review 2015

2015

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

25

TABLE 1. ESTIMATED DIRECT AND INDIRECT JOBS IN RENEWABLE ENERGY WORLDWIDE,

BY INDUSTRY, 2016-17

Source: IRENA jobs database.

Note: Figures provided in the table are the result of a comprehensive review of primary information sources by national entities such as ministries and statistical

agencies, and secondary data sources such as regional and global studies. This is an on-going effort to update and refine available knowledge. Totals may not add up

due to rounding.

a. Power and heat applications.

b. Traditional biomass is not included.

c. Although 10 MW is often used as a threshold, definitions are inconsistent

across countries.

d. Includes ground-based heat pumps for EU countries.

e. Direct jobs only.

f. Includes waste-to-energy (28 000), ocean energy (1 000) and jobs which

are not technology specific (8 000).

g. About 225 400 jobs in sugarcane processing and 168 000 in ethanol pro-

cessing in 2016; also includes rough estimate of 200 000 indirect jobs in

equipment manufacturing, and 202 000 jobs in biodiesel in 2017.

h. Includes 237 000 jobs for ethanol and about 62 200 jobs for biodiesel in 2017.

i. Based on employment-factor calculations for biomass power and CHP.

j. Combines small and large hydropower. Hence the country total with large

hydropower is the same as the total without large hydropower.

k. All EU data are from 2016, and include Germany.

The figure is derived from EurObserv’ER data, adjusted with national data for

Germany, the United Kingdom and Austria, as well as IRENA calculations.

l. EU hydropower data combine small and large facilities. Hence the

regional total with large hydropower is the same as the total without large

hydropower.

World

China Brazil

United

States India Germany Japan

Total

European

Union

k

Solar

Photovoltaic

3 365 2 216 10 233 164 36 272 100

Liquid

Biofuels

1 931 51 795

g

299

h

35 24 3 200

Wind

Power

1 148 510 34 106 61 160 5 344

Solar

Heating/

Cooling

807 670 42 13 17 8.9 0.7 34

Solid

Biomass

a,b

780 180 80

i

58 41 389

Biogas 344 145 7 85 41 71

Hydropower

(Small)

c

290 95 12 9.3 12 7.3

j

74

l

Geothermal

Energy

a,d

93 1.5 35 6.5 2 25

CSP

34 11 5.2 0.6 6

Total

(excluding Large

Hydropower)

8 829

f

3 880 893 786 432 332 283 1 268

Hydropower

(Large)

c, e

1 514 312 184 26 289 7.3

j

20 74

l

Total

(including Large

Hydropower)

10 343

4 192 1 076 812 721 332

j

303 1 268

l

RENEWABLE ENERGY AND JOBS – ANNUAL REVIEW 2018

26

REFERENCES

ABIOVE (Associação Brasileira das Indústrias de Óleos Vegetais)

(2018), “Biodiesel Production”, updated 7 March, www.abiove.com.

br/site/index.php?page=statistics&area=MTAtMi0x.

ABRASOL (Associação Brasileira de Energia Solar Térmica) (2018),

Communication with experts, March 2018.

Akata, M. N. (2018), Communication with experts, March 2018.

Alencar, C. A. (2013), “Solar Heating & Cooling Market in Brazil”,

presentation at Intersolar, September.

APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) (2010), “A Study

of Employment Opportunities from Biofuel Production in APEC

Economies”.

APPA (Asociación de Productores de Energía Renovables) (2017),

Estudio del Impacto Macroeconómico de las Energías Renovables en

España 2016, Madrid.

AWEA (American Wind Energy Association) (2018), US Wind

Industry Annual Market Report Year Ending 2017, April, Washington, DC.

Bermudez, V. (2018), “Japan, the new “El Dorado” of solar PV?”,

Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy Vol. 10, 020401 (2018),

doi: 10.1063/1.5024431.

Bhambhani, A. (2018), “Turkey Adds 2.6 GW PV in 2017 and Hits

2019 Target of 3 GW Capacity 2 Years Early; December 2017 Reports

Highest Capacity Addition in a Single Month with Nearly 1.2 GW”,

Taiyang News, 2 February, http://taiyangnews.info/markets/

turkish-pv-market-grows-over-300-in-2017/.

Blue Energy (2015), “Africa’s Largest Solar (PV) Power Plant”, 5 August,

http://www.blue-energyco.com/africas-largest-solar-pv-power-plant/.

BSW-Solar (Bundesverband Solarwirtschaft) (2016), “Statistische

Zahlen der deutschen Solarstrombranche (Photovoltaik)”, March,

www.solarwirtschaft.de/fileadmin/media/pdf/2016_3_BSW_Solar_

Faktenblatt_Photovoltaik.pdf.

BSW-Solar (2018), “Statistische Zahlen der deutschen

Solarstrombranche (Photovoltaik)”, February, www.solarwirtschaft.

de/fileadmin/user_upload/bsw_faktenblatt_pv_4018_4.pdf.

BNT (Bundesministerium für Nachhaltigkeit und Tourismus) (2017),

Erneuerbare Energie in Zahlen 2017 (Vienna, Austria, December).

CNREC (China National Renewable Energy Centre) (2018),

Communication with experts, March 2018.

Da Cunha, M. P., Guilhoto, J. J. M. and Da Silva Walter, A. C.

(2014), “Socioeconomic and environmental assessment of biodiesel

production in Brazil”, The 22nd International Input-Output Conference

14 18 July, Lisbon, Portugal.

Deloitte and Wind Europe (2017), Local Impact, Global Leadership.

The Impact of Wind Energy on Jobs and the EU Economy, November,

Brussels, windeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/files/about-wind/

reports/WindEurope-Local-impact-global-leadership.pdf.

Eckhouse, B. (2018), “Solar Jobs Are Rising, Despite Trump’s Taris”,

Renewable Energy World, 11 April, www.renewableenergyworld.com/

articles/2018/04/solar-jobs-are-rising-despite-trump-s-taris.html.

EIA (US Energy Information Administration) (2017), “Table 4.3.

Existing Capacity by Energy Source, 2016 (Megawatts)”, Electric

Power Annual, www.eia.gov/electricity/annual/.

EIA (2018), Monthly Biodiesel Production Report, www.eia.gov/

biofuels/biodiesel/production/biodiesel.pdf.

EnergyTrend (2018), “Japan’s Domestic PV Cell Shipments Dropped

Again by 18% YoY in 4Q17”, 1 March, https://pv.energytrend.com/

news/20180301-12199.html.

Enkhardt, S. (2018), “Germany installed 1.75 GW of PV in 2017”, PV

Magazine, 31 January.

Epp, B. (2018), “India: Flat plates up, concentrating technologies

down”, Solar Thermal World, 1 March, www.solarthermalworld.org/

content/india-flat-plates-concentrating-technologies-down.

EurObserv’ER (2018), The State of Renewable Energies in Europe,

2017 Edition, Paris, www.eurobserv-er.org/category/all-annual-

overview-barometers/.

FNBC (Federación Nacional de Biocombustibles de

Colombia) (n.d.), “Estadisticas”, accessed 5 March 2017,

www.fedebiocombustibles.com.

Foehringer Merchant, E. (2018), “Struggling US Polysilicon Producers are

a Forgotten Casualty in the Solar Trade War with China”, Greentechmedia,

29 March, www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/polysilicon-once-