June 2023

Final report

Airline competition

in Australia

ii

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

Ngunnawal

23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601

© Commonwealth of Australia 2023

This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence, with the exception of:

the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

the ACCC and AER logos

any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but

which may be part of or contained within this publication.

The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 4.0 AU licence.

Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Corporate Communications, ACCC, GPOBox 3131,

Canberra ACT 2601.

Important notice

The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied

on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain

professional advice if you have any specic concern.

The ACCC has made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding the

accuracy, currency or completeness of that information.

Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy prior to

publication. This should be done prior to each publication edition, as ACCC guidance and relevant transitional legislation frequently change. Any

queries parties have should be addressed to the Director, Corporate Communications, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601.

ACCC 06/23_23–38

www.accc.gov.au

Acknowledgment of country

The ACCC acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians of Country throughout

Australia and recognises their continuing connection to the land, sea and community. We pay

our respects tothem and their cultures; and to their Elders past, present and future.

iii

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Contents

Glossary iv

Key industry insights and developments 1

Executive summary 2

1. Introduction 4

1.1 The Government directed the ACCC to monitor domestic airline services 4

1.2 The ACCC’s broad work under the monitoring direction 4

2. Industry developments 6

2.1 Qantas Group expects to report a record prot in 2022–23 6

2.2 Bonza is now offering services on 27 routes 6

2.3 Industry faces pilot shortages and eet delays 8

2.4 Industry continues to report poor reliability 8

2.5 International market continues to recover but airfares remain high 11

2.6 ACCC opposes Qantas’ acquisition of Alliance 12

3. Key industry metrics and analysis 13

3.1 Passengers and capacity remain below pre-pandemic levels 13

3.2 Higher load factors in April compared to January 15

3.3 Bonza’s launch increases the number of Australian domestic routes 16

3.4 Half of all domestic passenger trips were on routes with 2 competing

airline groups 17

3.5 Qantas Group and Virgin Australia carried 94% of passengers in Australia 18

3.6 Airfares have fallen in recent months 20

4. State of competition in domestic airline services 23

4.1 Duopoly market structure has led to minimal competition between airlines 23

4.2 Outcomes delivered by the domestic airline industry have been

underwhelming 25

4.3 Rex and Bonza would need to grow if Australia is to have more effective

competition 27

4.4 Legislative and policy changes could encourage further airline competition and

improve outcomes for consumers 28

iv

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Glossary

ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics

BITRE Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics

CASA Civil Aviation Safety Authority

CCA Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)

Larger city Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth, Canberra or the Gold

Coast

Load factor The total number of passengers as a proportion of the total number of

seats own across all airlines

Qantas Qantas domestic passenger airlines that include Qantas Domestic and

QantasLink airlines

Qantas Group Qantas Domestic, QantasLink and Jetstar Domestic airlines

Regional Domestic locations other than Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide,

Perth, Canberra and the Gold Coast

TANS Tourism and Aviation Network Support Program. An Australian

Government program introduced in response to COVID-19 to reduce the

costs for consumers to y to key tourism regions

Virgin Australia Virgin Australia domestic passenger airlines that include Virgin Australia

and Virgin Australia Regional Airlines (VARA). Virgin Australia also

operated Tigerair until March 2020

Wet lease An agreement whereby an airline leases an aircraft and crew

1

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Key industry insights and

developments

Passenger and capacity gures yet to recover to

pre-pandemic levels

Over a year following the end of state border restrictions, domestic passenger and capacity

gures have not managed to reach pre‑pandemic levels. 4.6 million passengers ew in April

2023, 92% of April 2019 levels. The industry ew 6 million seats, 93% of April 2019 levels.

Airfares continue to fall

Domestic airfares have fallen signicantly in 2023 as pent‑up demand for travel eases

and the price of jet fuel has decreased. However, average revenue per passenger and

discounted economy airfares remain higher than pre-pandemic levels, even after adjusting

for ination.

Service reliability remains relatively poor

The latest cancellation and delay rates have gotten worse again, with industry performance

remaining poor compared to long‑term averages. The industry cancelled 3.9% of ights

in April 2023, with only 71.8% of ights arriving on‑time. Jetstar reported notably worse

cancellation rates than other airlines.

Domestic airline competition is at a critical juncture

Other than natural monopolies, the domestic airline industry is one of the most

concentrated industries in Australia. The expansion of Rex and the entry of Bonza

have created the opportunity for a more competitive era, but they would need to grow

signicantly to become more meaningful competitors to Qantas Group and Virgin Australia.

Legislative and policy reform could promote competition and

better protect consumers

The Australian Government could promote competition by implementing reforms to

help new and expanding airlines obtain slots at Sydney Airport. The government could

also incentivise airlines to improve their customer service by introducing an effective

independent dispute resolution ombuds scheme.

2

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Executive summary

More than a year since the end of the nal COVID‑19 state border restrictions, the domestic airline

industry has not yet managed to recover to pre-pandemic levels of passengers and capacity.

4.6 million passengers ew in April 2023, 92% of pre‑pandemic levels, and only marginally more than

this time last year. The industry ew 6 million seats in April 2023, 93% of pre‑pandemic levels, and the

same number as last year.

This stagnation can be explained by both demand-side and supply-side factors. Last year, demand

was strong following years of COVID-19 related movement restrictions. However, the industry

struggled to increase capacity without signicantly compromising reliability due to labour market

shortages and high levels of staff absences due to illness. More recently, it appears that the pent-up

demand for leisure travel that characterised much of 2022 is beginning to ease. Increasing cost of

living pressures have also led to consumers becoming more price sensitive.

This easing of demand is evident in the fall in airfares throughout 2023 to date. The price of discount

airfares decreased by 14% in real terms between February and May 2023. Average revenue per

passenger, which represents average prices across all fare types, has also declined this year. Both of

these measures remain above pre-pandemic levels. A reduction in the price of jet fuel by almost half

since its peak in June 2022 has also led to declining airfares.

While the industry ew below pre‑pandemic levels of seat capacity, the industry load factor, a

measure of total passengers as a proportion of total seat capacity, was 77% in April 2023. This is

similar to pre-pandemic levels and below the high load factors reported in mid-2022 (83%).

Some of the lag in recovery may also be due to a structural change in which online technology

continues to replace some business travel.

After showing signs of improvements earlier in the year, the latest rates of ight cancellations and

delays have gotten worse and remain poor compared to long-term industry averages. The industry

cancelled 3.9% of ights in April 2023, compared with the industry long‑term average of 2.1%. Jetstar

continued to perform signicantly worse than the rest of the industry. It cancelled 8.1% of ights in

April, more than double the rate of the other airlines.

The industry reported that only 71.8% of ights arrived on‑time in April, well below the industry

long‑term average of 81.5%. Jetstar reported only 59.7% of ights arriving on‑time. Jetstar has

acknowledged it needs to do more to improve punctuality, including investing in new aircraft,

recruiting more staff in customer service, engineering and operational roles, and upgrading its

systems and processes.

New low-cost airline Bonza is now offering services on all 27 routes within its planned initial network

after commencing regular services in February 2023. For many consumers, the primary benet of

Bonza’s entry will be its low airfares and direct connections on new regional routes. Bonza is also

offering extra choice and competition on 2 routes served by other airlines – Melbourne to Sunshine

Coast and Mildura.

The duopoly market structure of the domestic airline industry has made it one of the most highly

concentrated industries in Australia, other than natural monopolies. The lack of effective competition

over the last decade has resulted in underwhelming outcomes for consumers in terms of airfares,

reliability of services and customer service.

The expansion of Rex and the entry of Bonza in recent years have created the opportunity for the

industry to enter a more competitive period. However, both would need to expand signicantly if they

are to become more meaningful competitors to the Qantas Group and Virgin Australia.

3

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

The Australian Government is currently considering various aviation policies as part of its Aviation

White Paper process and the review of the demand management scheme at Sydney Airport. The best

way to promote competition for the benet of consumers would be to implement reforms already

identied by the review which would help new and expanding airlines to better access take‑off and

landing slots at Sydney Airport. Separately, consumers would be better able to resolve disputes with

airlines, and airlines would be incentivised to provide improved customer service, if there was an

effective independent dispute resolution ombuds scheme.

Under direction from the Australian Government, the ACCC has been monitoring and reporting on

the domestic airline industry for the last 3 years. This is our 12th and nal report under the direction,

which expires at the end of June 2023.

Our monitoring role has signicantly expanded the ACCC’s knowledge of the airline industry, and

we have developed a deep understanding of airline practices that may contravene the Competition

and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). While the Australian Government’s direction is expiring, the ACCC will

continue to watch the airlines’ conduct and where necessary use our broad enforcement powers to

take action to achieve compliance with competition law and the Australian Consumer Law.

4

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

1. Introduction

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is an independent Commonwealth

statutory agency that promotes competition, fair trading and product safety for the benet of

consumers, businesses and the Australian community. The primary responsibilities of the ACCC are

to enforce compliance with the competition, consumer protection, fair trading and product safety

provisions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA), regulate national infrastructure and

undertake market studies.

On 19 June 2020 the then Treasurer directed the ACCC under subsection 95ZE(1) of the CCA

to monitor prices, costs and prots relating to the supply of domestic air passenger transport

services for 3 years. The direction also requires the ACCC to report on its monitoring at least once

every quarter.

In announcing the direction, the Treasurer said that the ACCC’s monitoring will assist in protecting

competition in the sector for the benet of all Australian airline travellers.

1

The Treasurer also said

that the reporting role and focus by the ACCC would provide another avenue for those wishing to

raise concerns about anti-competitive conduct in the sector.

The monitoring direction expires at the end of June 2023. This is the 12th and last report under

the direction.

The ACCC has carried out a broad range of work within the scope of the monitoring direction.

We collected data on a monthly basis from Rex, Virgin Australia and Qantas Group from the outset

of the regime, with Bonza providing data once it commenced operations in 2023. The data included

the number of passengers and revenues for each ight, monthly reliability performance and quarterly

prot and loss results. The ACCC has appreciated the cooperation of the airlines in agreeing to

provide this information on a voluntary basis and meeting with the ACCC quarterly to discuss industry

trends and developments.

We collected other information from the airlines using the ACCC’s formal information gathering

powers enlivened by the monitoring direction. This information was collected on an as-needed basis

and included items such as documents prepared for the company’s board of directors with respect to

operations and competitive strategies. Cost data was also collected from some airlines on routes of

particular interest to enable analysis of prot margins.

The ACCC published quarterly reports on its ndings as required by the direction. Our 12 reports

have covered signicant industry developments, such as the considerable nancial and operational

impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the airline industry and the subsequent developments. We

have reported on the key drivers impacting competition, airfares, service levels and consumer

1 The Hon. Josh Frydenberg (the former Treasurer), ACCC directed to monitor domestic air passenger services [media release],

19 June 2020, accessed 21 November 2021.

5

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

choice as the industry navigated and emerged from the pandemic. For example, the emergence of

Virgin Australia from voluntary administration, expansion of Rex to intercity routes, Bonza’s entry on

unserved and underserved routes, high fuel prices, and the operational issues the aviation industry

faced when ying returned after travel restrictions were eased.

Our reports have also highlighted opportunities to stimulate competition, such as improving the

slot management scheme at Sydney Airport. These remain pertinent issues today, as discussed in

Chapter 4.

The insight into the domestic airline industry enabled the ACCC to engage with various government

and policy processes. In particular, the ACCC engaged extensively with the review of the demand

management scheme at Sydney Airport by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional

Development, Communications and the Arts. The ACCC made an initial submission and then later

participated in working groups with key stakeholders to consider issues such as how take-off and

landing slots should be allocated between airlines. Separately, the ACCC made a submission to the

Australian Government’s Aviation White Paper process and participated in the Senate inquiry into the

impact of COVID-19 on the aviation sector.

The ACCC’s monitoring role has also been complementary to its enforcement of competition law

under Part IV of the CCA and consumer rights under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). The ACCC

has undertaken investigations into conduct within the industry over this time, which have arisen from

concerns raised by the public, industry participants, and identied by the ACCC through its analysis of

monitoring information.

The ACCC investigated whether Qantas’ entry and expansion on certain routes in competition with

Rex in late 2020 and early 2021 was a misuse of market power in contravention of competition law.

In closing the investigation, we noted that a range of factors impacted competitive dynamics at the

time, particularly the COVID-19 related movement restrictions and border closures.

2

The ACCC is continuing to investigate a number of issues that consumers have raised about Qantas,

and whether these issues raise concerns under the ACL.

Our monitoring role has signicantly expanded the ACCC’s knowledge of the airline industry, and we

have developed a deep understanding of airline practices that may contravene the CCA. While the

Australian Government’s direction is expiring, the ACCC will continue to watch how airlines compete

for and treat consumers and, where necessary, take action to ensure compliance with the CCA.

2 ACCC, Airline competition in Australia – June 2022 report, 8 June 2022.

6

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

2. Industry developments

In May the Qantas Group reported that it is expecting to report an underlying prot before tax of

$2.425–2.465 billion for the full 2022–23 nancial year.

3

This result captures performance across the

whole business, including international and domestic ying (including Jetstar), freight and the loyalty

program. This forecast is close to $1 billion higher than its prior record result in 2018. The Qantas

Group previously reported a record $1.43 billion prot for the rst half of the 2022–23 nancial year.

The Qantas Group said that yields

4

are expected to remain materially above pre-pandemic levels

through to the next nancial year, particularly for international services. Based on revenue intakes

over April–May, yields from domestic travel are 118% of pre-pandemic levels, and 125% for

international travel.

5

While strong demand and high airfares across the industry have been a key reason for the Qantas

Group’s strong protable performance, it may also reect a change in the competitive landscape

since early 2020. Following Virgin Australia’s restructure in late 2020, the airline repositioned

its strategy towards the middle of the market, targeting small medium enterprise (SME) and

price-conscious corporate, as well as premium leisure customers. This downward shift may have

allowed Qantas to gain a greater share of the more lucrative larger corporate customer segment. The

exit of Tigerair in March 2020 may have similarly allowed Jetstar to gain a greater share of the budget

leisure customer segment.

The Qantas Group reported that it expects to increase to 108% of pre-pandemic domestic capacity

between July–December 2023.

6

The ACCC can report that Qantas reached 101% of its pre-pandemic

domestic capacity in April 2023, compared to 96% for Virgin Australia and 85% for Jetstar.

7

New low-cost airline Bonza is now offering services on all 27 routes within its planned initial network

after commencing regular services in February 2023. Currently, Bonza has a eet of four 737 MAX

8s ying to 17 locations connecting regional hubs to holiday destinations across Queensland, New

South Wales and Victoria.

In late March Bonza established its second base at Melbourne’s Tullamarine Airport. This expansion

added 12 routes to its network, with the new routes from Melbourne including Bundaberg, Mildura,

Rockhampton and Tamworth. Bonza has also introduced direct connections on routes such as

3 Qantas, Qantas Group market update: Strong performance supports eet investment, shareholder returns [media release],

23 May 2023, accessed 23 May 2023.

4 ‘Yield’ is calculated by dividing revenue by revenue passenger kilometres (RPK). RPK refers to the number of paying

passengers carried on ights multiplied by the number of kilometres those seats were own.

5 Qantas, Qantas Group market update: Strong performance supports eet investment, shareholder returns [media release],

23 May 2023, accessed 23 May 2023.

6 ibid.

7 Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar and Virgin Australia. Compared with April 2019 capacity gures; Virgin

Australia gure excludes Tigerair.

7

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Sunshine Coast to Albury and Coffs Harbour as well as Toowoomba Wellcamp to Townsville, the

Whitsundays and the Sunshine Coast.

CEO Tim Jordan reported that within its rst few months of operation, Bonza had reached a

milestone of 100,000 seat sales on its Fly Bonza app.

8

Bonza’s cheapest available one-way fares

typically range from $49 to $89 without checked-in luggage. Bonza has also offered promotional

fares for $29.

Bonza’s launch is a signicant development in the history of Australia’s airline industry. Bonza is the

rst high‑capacity passenger airline to enter the domestic market since Tigerair 15 years ago. Bonza

is also the rst independent low‑cost carrier in the market since Virgin Australia acquired Tigerair in

2013. Tigerair has since exited the market.

For many consumers, the primary benet of the new airline is through the additional connectivity.

Consumers living near one of the 17 locations now have more direct ights for holidays and visiting

family and friends. Some of these direct ights will replace long car trips, or otherwise encourage

consumers to y when they otherwise would not.

Bonza competes directly with other airlines on the following 2 contested routes:

Melbourne – Sunshine Coast, currently operated by Qantas, Virgin Australia and Jetstar

Melbourne – Mildura, currently operated by Qantas and Rex.

To date, Bonza’s minimum one-way fares were well below the fares of its competitors. The ACCC

has observed that, between January to May 2023, Bonza offered the cheapest one-way fares from

$79 on the Melbourne – Sunshine Coast route, in comparison to low-cost carrier Jetstar offering

fares from $99. The cheapest observed airfares from Virgin Australia and Qantas were from $109

and $241 respectively.

9

Further, since its entry on the Melbourne – Mildura route in early May, Bonza’s

minimum one-way fares for $49 have been less than a quarter of its competitors’ fares.

10

As well as having an additional choice of airline, travellers on these 2 routes may also benet from a

competitive response from the other airlines such as reduced airfares on specic routes. However,

any response may be somewhat limited given that Bonza is currently only offering 2–5 ights per

week on each route.

Although not part of its stated strategy, Bonza may expand into more contested routes in the future,

including possibly larger inter‑city routes. This would pose a more signicant competitive threat to

the other airlines. It expects to have 8 aircraft by early 2024.

11

The response by other airlines to new competition will remain of interest to the ACCC beyond

the expiration of the monitoring direction. Where an airline enters or increases capacity or

decreases prices on a route serviced by a new competitor, or where an airline enters into exclusive

arrangements with service providers, the ACCC may investigate whether this practice is anti-

competitive and contravenes competition law.

8 Bonza, Bonza’s second base at Melbourne Tullamarine launches today with rst ight to the Sunshine Coast [media release],

30 March 2023, accessed 12 May 2023.

9 Minimum economy one-way fares on Melbourne – Sunshine Coast collected by ACCC (2 weeks ahead of departure

date) from the airlines’ websites and app for January – May 2023. Fares for Bonza, Jetstar and Virgin Australia excluded

checked-in luggage.

10 Minimum economy one-way fares on Melbourne – Mildura collected by ACCC (2 weeks ahead of departure date) from the

airlines’ websites and app for January – May 2023. The ACCC has observed that in the months prior to Bonza’s entry, Qantas

and Rex offered fares from $217 and $209 respectively. Fares for Qantas and Rex included checked-in luggage.

11 Baird, L, Australian Financial Review, ‘777’s Canadian budget carrier stumbles, and Bonza loses an aircraft’, 10 April 2023,

accessed 12 May 2023.

8

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

The industry is facing challenges due to shortages in qualied and experienced Australian pilots and

engineers, as well as the supply chain issues that have persisted from last year.

Rex suspended Adelaide – Mildura in May 2023, citing challenges with pilot and engineer shortages,

as well as a severe disruption in the supply chain of aircraft and engine parts. Rex also announced

a reduction of services on 9 other regional routes across New South Wales, Queensland, South

Australia and Victoria.

12

These challenges are impacting Rex’s Saab eet rather than the Boeing 737s

it uses to service its intercity network. Rex also announced it was exiting Adelaide – Whyalla, however

Rex said this is due to an increase in airport security costs at Whyalla airport.

13

While Rex reported

challenges on its regional network, the airline announced it is adding Adelaide – Sydney to its intercity

network from late June, which is made possible with the arrival of 2 additional 2 x 737s. The route is

currently operated by Qantas, Jetstar and Virgin Australia.

14

The Australian and International Pilots Association and the Australian Federation of Air Pilots have

recently reported that hundreds of experienced pilots are leaving Australia for overseas roles,

including under the US Government’s E3 Visa program.

15

These pilot retention challenges are being

amplied by a shortfall in new trained pilots.

Qantas recently conrmed its new ight training centre in Sydney to help meet increased demand for

pilots and cabin crew as the group introduces next generation aircraft and grows its network. Noting

it will need a pipeline of engineers to support growth and attrition, the Qantas Group announced it

was establishing an Engineering Academy with capacity to train up to 300 engineers a year, starting

in 2025.

16

Qantas and Virgin Australia have also reported global supply chain issues, which are impacting the

arrival of new eet. Qantas previously announced orders and purchase right options of up to 299

narrowbody and 12 widebody aircraft to replace and expand existing eet over the next 10 plus years.

Citing rolling delays of up to 6 months, Qantas announced changes to its plans including wet leasing

additional E190 aircraft from Alliance Airlines to boost domestic capacity and purchasing midlife

A319/320 aircraft to support growth of the Western Australian resources market.

17

Virgin Australia

previously announced it was acquiring 8 x Boeing 737 MAX 8s, all expected to arrive in 2023.

However, delays in manufacturing from Boeing are impacting the timing of aircraft delivery.

18

After showing signs of improvements earlier in the year, the latest airline cancellation and delay rates

have gotten worse and remain poor compared to the long-term industry averages.

Figure 1 shows that the industry cancelled 3.9% of ights in April 2023 (over 1,700 cancelled ights),

above the industry long-term average of 2.1%.

12 Rex, Rex adjusts regional network [media release], 21 April 2023, accessed 18 May 2023.

13 Rex, Rex exists Whyalla – Adelaide route due to Council imposed security charges [media release], 18 May 2023, accessed

18 May 2023.

14 Rex, Rex to y Adelaide‑Sydney [media release], 29 May 2023, accessed 30 May 2023.

15 Australian & International Pilots Association (AIPA) submission to Australian Government’s Aviation White Paper terms of

reference, 17 March 2023; Australian Federation of Air Pilots (AFAP) submission to the Australian Government’s Aviation

White Paper terms of reference, March 2023, accessed 9 May 2023.

16 Qantas, Qantas Group announces major jobs, training and growth plans [media release], 3 March 2023, accessed

19 May 2023.

17 Qantas, Qantas gears up for more training as new Sydney ight training centre breaks ground [media release], 19 May 2023,

Qantas, Qantas Group updates eet plan to boost capacity [media release], 23 February 2023, accessed 9 May 2023.

18 Ironside, R, NT News, ‘Virgin Australia’s nervous wait for new Boeing 737 Max 8s’, 1 May 2023, accessed 9 May 2023.

9

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 1 Airline cancellation rates – April 2022 to April 2023

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Apr–22 May–22 Jun–22 Jul–22 Aug–22 Sep–22 Oct–22 Nov–22 Dec–22 Jan–23 Feb–23 Mar–23 Apr–23

Qantas Jetstar Virgin Rex Bonza Industry average Industry long term average

Cancellation rate (%)

Note: A ight is regarded as a cancellation if it is cancelled or rescheduled less than 7 days prior to its scheduled departure

time. The industry total and long‑term average is weighted across all airlines and all airports; and presented at the

April 2023 level for all months.

Source: BITRE, On‑time performance time series – April 2023; data collected by the ACCC from Bonza. Qantas gures include

QantasLink and Virgin Australia gures include VARA.

Jetstar continued to perform signicantly worse than the rest of the industry, cancelling 8.1% of

ights in April, more than double the cancellation rate of the other airlines. Bonza cancelled 0.5%,

followed by Rex 2.8%, Virgin Australia 3.1% and Qantas 3.3%.

Figure 2 shows that the industry reported an average of 71.8% of ights arriving on‑time in April. This

represents more than 12,000 ights arrived more than 15 minutes late. This is below the industry

long term average of 81.5%. Despite a substantial improvement in January, on-time arrival rates have

declined to April.

10

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 2 Airline on-time performance rates (arrivals)– April 2022 to April 2023

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Apr–22 May–22 Jun–22 Jul–22 Aug–22 Sep–22 Oct–22 Nov–22 Dec–22 Jan–23 Feb–23 Mar–23 Apr–23

Qantas Jetstar Virgin Rex Bonza Industry average Industry long term average

On-time performance rate (arrivals) (%)

Note: A ight arrival is considered on‑time if it arrives within 15 minutes of the scheduled arrival time shown on the airline’s

schedule. The industry total and long‑term average is weighted across all airlines and all airports; and presented at the

April 2023 level for all months.

Source: BITRE, On‑time performance time series – April 2023; data collected by the ACCC from Bonza. Qantas gures include

QantasLink and Virgin Australia gures include VARA.

Jetstar has struggled with its on‑time performance over the last year, with only 59.7% of its ights

arriving on-time in April 2023. To improve reliability, Jetstar announced in May that it was recruiting

more airport staff, cabin crew and engineering team members, as well as making changes to its

check-in, bag drop and boarding times.

19

New airline Bonza reported a decline in its on-time performance in April as it launched an additional

8 routes on its network. Bonza reported 50.7% of its ights arrived late in April. Qantas was the best

on-time performer reporting 78.4%, followed by Rex 73.2% and Virgin Australia 67.6%.

Performance on routes to and from Sydney continues to be especially poor. In April 2023 the industry

cancelled 9.2% of ights between Sydney and Melbourne, 8.8% of ights between Sydney and

Canberra, and 5.7% of ights between Sydney and Brisbane. A third of all ights were delayed on

routes connecting Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney.

Several factors can impact service reliability, including the capability of the airlines, airports, air trac

control as well as external factors such as the weather.

The airlines have reported that air trac control staff absences have impacted reliability, particularly

at Sydney Airport.

20

As the busiest and most connected hub, delays at Sydney Airport have ow on

effects on other routes.

Data published by Airservices Australia shows it was responsible for around a third of total ground

delay hours at Sydney Airport in February. This improved to 6% in March and 4% in April. Airservices

Australia data shows it was responsible for 65% of total ground delay hours at Brisbane Airport in

April.

21

19 Jetstar, Jetstar boosts reliability and punctuality with seventh Airbus A321neo LR and check-in time changes, [media release],

16 May 2023, accessed 18 May 2023.

20 Qantas, Industry update – Flying Kangaroo most on-time airline again as airline gears up for Easter [media release],

22 March 2023; Virgin Australia submission to the Australian Government’s Aviation White Paper terms of reference,

17 March 2023, accessed 10 May 2023.

21 Butler Caroye, ‘Australian domestic air travel pain index’, April 2023, accessed 10 May 2023; Airservices Australia, ‘Air Trac

Management (ATM) performance report – April 2023’, accessed 16 May 2023.

11

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

In May the Sydney Airport CEO reported that security processing times at the airport are faster than

they were before the pandemic, partially because the airport is more ecient.

22

International air travel continues to recover but is lagging behind the recovery of domestic market and

airfares remain high. In May 2023 international arrivals and departures recovered to 81% and 79%,

respectively, compared to the same month pre-pandemic.

23

Sydney Airport reported that international passenger trac recovered to 80.6% of pre‑pandemic

levels in April 2023. Trac to and from China has also rebounded strongly since the country

reopened its borders from January 2023. When comparing the passenger volumes of the same

month pre‑pandemic, the number of Chinese travellers ying through Sydney Airport reached 53.8%

of pre-pandemic levels in April 2023.

24

Australian airlines are continuing to increase their international capacity. Virgin Australia is expanding

its short-haul international network, now operating to Bali, Queenstown, Samoa, Fiji and Vanuatu. The

airline is scheduled to start ying Cairns – Tokyo in late June. With these additional services, Virgin

Australia will increase its international capacity by 50% from FY23 to FY24.

25

Virgin Australia will soon

acquire 8 x 176‑seater MAX 8 jets. As well as having more capacity, the MAX8 jets can y a longer

range, which will allow Virgin Australia to expand its network reach.

The Qantas Group announced it ew 84% of its pre‑pandemic international capacity in mid‑May.

Qantas launched new route Melbourne – Jakarta in April, the fourth route out of Melbourne that

Qantas has added to its international network since borders reopened. Qantas is due to launch

Brisbane – Wellington, Brisbane – Solomon Islands and Sydney – Auckland – New York later this

month. Jetstar entered Brisbane – Auckland in March and is due to launch Sydney – Cook Islands

in late June. The Qantas Group expects to reach 100% of its pre-pandemic international capacity

by March 2024. This is aided by Qantas adding an estimated one million seats on its international

network from October 2023 onwards.

26

While domestic airfares having reduced slightly from their peak in late 2022 (see section 3.6),

international airfares remain high. It was reported in late May that the average return economy

international airfare from Australia was $1,827 compared with $1,213 in 2019, an increase of 51%.

27

While the industry has increased international capacity over the past few months, capacity remains

below pre-pandemic levels due in part to delays in aircraft and spare parts shortages. Qantas has

also reported that demand for international travel remains strong, leading to a mismatch between

demand and supply.

28

This imbalance is putting upward pressure on international airfares.

22 Wiggins, J, Australian Financial Review, ‘Sky-high airfares ‘will come down’, says Sydney Airport boss’, 12 May 2023,

accessed 16 May 2023.

23 Based on the total number of international border crossings in March 2023 compared with March 2019, ABS, Australian

Government, ‘Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia’, March 2023, accessed 19 May 2023.

24 Sydney Airport, ‘Sydney Airport Trac Performance April 2023’, accessed 19 May 2023.

25 Virgin Australia, Like a virgin, Virgin Australia takes off with Gold Coast-Bali ights “for the very rst time”, drops fares from

$419 return* [media release], 29 March 2023; Ironside, R, NT News, ‘Virgin Australia’s nervous wait for new Boeing 737 Max

8s’, 1 May 2023, accessed 8 May 2023.

26 Qantas, Qantas ights take off from Melbourne to Jakarta [media release], 16 April 2023; Qantas, Qantas: Boosts international

network: Restoring capacity, adding more aircraft, launching new routes [media release], 19 May 2023; Jetstar, Jetstar’s new

Auckland to Brisbane service takes off [media release], 27 March 2023; Jetstar, Jetstar to take off from Sydney to the Cook

Islands non-stop [media release], 1 December 2022, accessed 12 May 2023.

27 Barret, J, The Guardian, ‘Why Australians are paying 50% more for air fares than pre-pandemic even as jet fuel costs drop’,

31 May 2023, accessed 31 May 2023.

28 Qantas, Qantas Group market update: Strong performance supports eet investment, shareholder returns [media release],

23 May 2023, accessed 23 May 2023.

12

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

On 5 May 2022 Qantas announced that it had reached an agreement to acquire the remaining shares

in Alliance Airlines, after acquiring a 19.9% holding in 2019. Alliance.Qantas and Alliance are key

suppliers of air transport services to mining and resource companies who need to transport ‘y‑in

y‑out’ workers to remote and regional locations in Western Australia and Queensland.

After a thorough investigation of the proposed acquisition, on 20 April 2023 the ACCC announced

that it opposed the proposed acquisition as it is likely to substantially lessen competition in markets

for the supply of charter air transport services to resource industry customers in Western Australia

and Queensland.

29

The ACCC considered that Alliance is an important competitor to Qantas, and the proposed

acquisition would combine 2 of the largest suppliers of charter services in Western Australia

and Queensland.

The ACCC considered that Qantas will face limited competition if allowed to acquire Alliance because

most other airlines lack the right aircraft, eet size, or capabilities needed to compete effectively. The

ACCC found that it is unlikely that a new or existing airline could expand quickly to a scale that would

address the loss of competition resulting from the proposed acquisition. Airlines wanting to enter

or expand at scale, face a combination of barriers, including incumbency advantages, the need to

establish a reputation for providing a reliable service, access to and training of air crew and engineers,

access to suitable aircraft and infrastructure, and the signicant regulatory requirements to y.

29 ACCC, ACCC opposes Qantas’ acquisition of Alliance [media release], 20 April 2023.

13

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

3. Key industry metrics and

analysis

This chapter presents analysis of key industry metrics. Unless specied otherwise, we calculate these

metrics from data supplied to the ACCC on a monthly and quarterly basis from:

the Qantas Group (comprising Qantas and Jetstar)

Virgin Australia (including Tigerair until March 2020)

Rex

Bonza (from February 2023).

This chapter draws from data collected by the ACCC up to April 2023. Section 3.6 includes analysis of

airfare trends using BITRE data up to May 2023.

The domestic airline sector carried 4.6 million passengers in April 2023, which was an increase of

200,000 passengers from January. Figure 3 shows that while seasonal demand typically increases in

April, this year there was a decrease of 100,000 passengers in April compared to March.

Figure 3 Australian domestic air services – January 2019 to April 2023

2019 2020 2021 2022

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov Dec

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov Dec

Millions

Passengers

Seat capacity

2023

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

14

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

While it has been over a year since the last of the state border restrictions were lifted in Australia, the

number of monthly passengers in April 2023 was the same as in April last year. The chart also shows

the industry is yet to reach pre-pandemic passenger levels.

The airlines ew 6.0 million seats in April, which was 100,000 more than in January and the industry’s

highest capacity since May 2022. However, the typical monthly increase in capacity between March

and April did not eventuate this year. As a result, capacity also remains below pre-pandemic levels for

the sector.

Figure 4 shows the passengers and capacity gures as a proportion of their respective 2019 monthly

levels. It shows the recovery to date peaked in June 2022 with passengers at 97% and capacity at

95% of their 2019 levels. The industry found that it was not able to sustain that level of ying with

reduced workforces and other operational challenges following the pandemic, resulting in very high

rates of cancellations, delays and lost bags. After quickly scaling back scheduled ying, the recovery

has since occurred at a more gradual rate, with capacity generally leading the recovery in passengers.

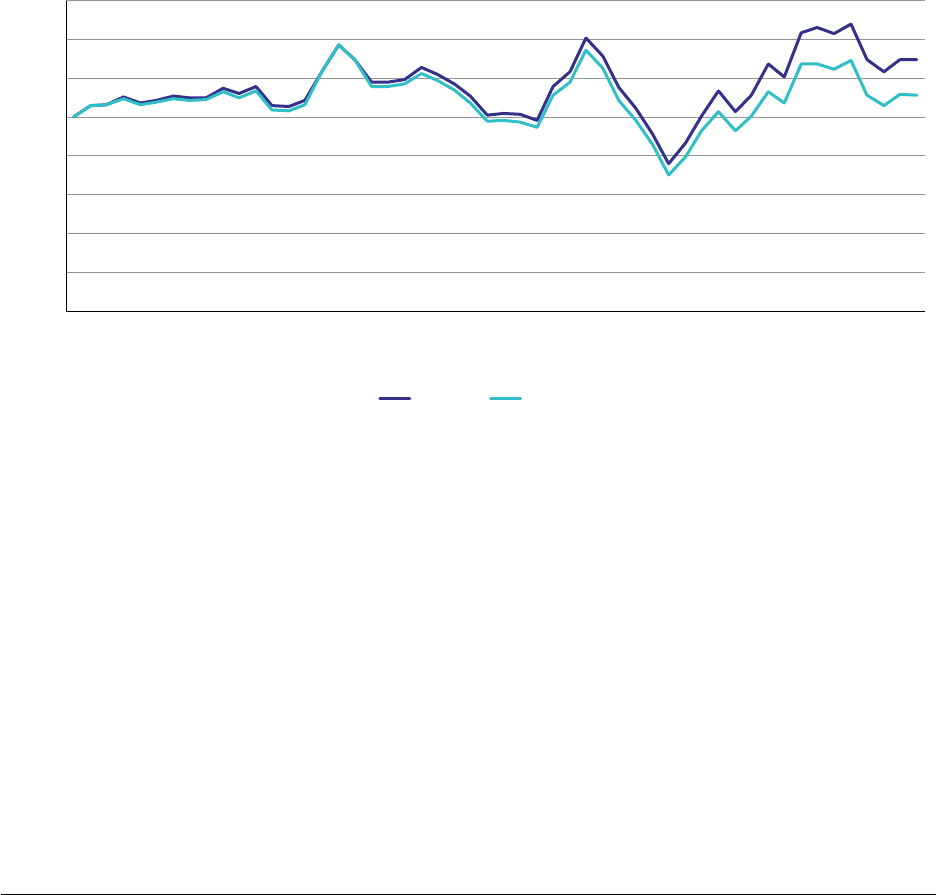

Figure 4 Passengers and seat capacity as a proportion of 2019 levels – January 2022 to April 2023

0

Jan–22

Feb–22

Mar–22

Apr–22

May–22

Jun–22

Jul–22

Aug–22

Sep–22

Oct–22

Nov–22

Dec–22

Jan–23

Feb–23

Mar–23

Apr–23

Compared with 2019 (%)

Passengers Seat capacity

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

100

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

The industry has still yet to fully recover, with passenger and seat capacity recovery gures at 92%

and 93% of pre‑COVID‑19 levels respectively in April 2023. This may partly reect changes in the

sector following the pandemic such as the movement of staff and labour into other less severely

impacted industries and a potentially sustained reduction in corporate travel demand.

15

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

The increase in passenger numbers between January and April was more than the increase in

seating capacity. As a result, the load factor, which measures the proportion of seats that were

lled, increased slightly from 75% in January to 77% in April 2023. The load factor in April 2023 was

1 percentage point below that in April 2019.

There were 5 routes with a load factor of 90% or higher in April 2023, up from 2 in the same month

prior to the pandemic (April 2019). The 5 routes included popular Queensland holiday destinations

such as the Gold Coast and the Whitsundays. This result was also slightly lower compared to

April 2022, when there were 7 such routes. All were routes in and out of Western Australia at the time,

following the state opening its border in March 2022.

Figure 5 ranks the routes connecting larger cities by the degree to which they have recovered to

their pre-COVID-19 levels of passengers. There were 5 routes which reached 100% of pre-COVID-19

passenger levels. These included 3 routes to/from the Gold Coast and 2 routes to/from Perth.

Figure 5 Passengers on routes connecting larger cities – April 2019 compared to April 2023

Passengers Passenger recovery (%)

0 50

% of pre-COVID-19

0

Apr–19 Apr–23

//

250,000500,000750,000

AVV SYD

CBR SYD

CBR PER

CBR MEL

MEL SYD

BNE SYD

ADL SYD

OOL SYD

ADL BNE

BNE MEL

MEL PER

PER SYD

ADL MEL

BNE CBR

AVV OOL

ADL CBR

MEL OOL

ADL PER

BNE PER

ADL OOL

CBR OOL

II

100

OOL PER

233%

131%

II

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

The 3 largest routes in Australia – those connecting Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney – are

continuing to lag in their passenger volume recovery compared to other routes connecting larger

cities. Melbourne – Sydney continues to be the worst performing of the 3 with passengers in April

2023 equivalent to 84% of pre-COVID-19 levels.

While this was an improvement in recovery compared to January 2023, it was still 7 percentage

points below the national average for April 2023. It continues to reect the greater historical

signicance of business travel on these routes, with demand for business travel returning more

slowly than leisure travel. It might also represent a structural change in demand for business travel.

16

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 6 shows the 10 busiest routes in Australia in April 2023 by passenger volume. Melbourne –

Sydney continues to be the busiest route with 577,000 passengers in April 2023 representing 13% of

all domestic passengers in Australia. The top 10 routes continue to be the same as in 2019.

Figure 6 Busiest routes by monthly passengers – April 2023

Hobart Melbourne

Melbourne Sydney

April 2023

Sydney

Melbourne

Adelaide

Perth

Brisbane

Gold

Coast

Passengers (Millions)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6

Perth Sydney

Adelaide Sydney

Melbourne Perth

Gold Coast Melbourne

Adelaide Melbourne

Gold Coast Sydney

Brisbane Melbourne

Brisbane Sydney

Hobart

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

The launch of new routes by Bonza has recently broadened the choice of domestic routes for

Australia domestic passengers. There were 176 routes in operation in Australia in April 2023, up from

154 in January 2023. This compares to 160 routes prior to the pandemic in April 2019.

The bulk of the increase was attributable to Bonza, which had commenced operations on 20 of its

proposed routes by the end of April 2023. Out of the 20 routes, 12 were from Bonza’s Sunshine Coast

base including services to Melbourne’s Tullamarine and Avalon airports, followed by 6 Queensland

intrastate routes and 2 other routes from its Melbourne base. As discussed in section 2.2, Bonza

has since commenced operations on all 27 of its planned routes, with only 2 of these routes already

offered by other airlines.

Figure 7 shows Qantas had the largest route network with 118 routes serviced in April 2023, a

slight increase from 116 in January. The airline has signicantly grown its network since prior to the

pandemic by entering more regional routes, reaching a peak in early 2022. The uctuations in its

network between January and April were largely attributable to the operation of seasonal services to

meet leisure demand. These included routes to destinations such as Broome, Launceston and the

Sunshine Coast.

17

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 7 Number of domestic routes operated by airlines – January 2019 to April 2023

Number of routes

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Jan–19

Mar–19

May–19

Jul–19

Sep–19

Nov–19

Jan–20

Mar–20

May–20

Jul–20

Sep–20

Nov–20

Jan–21

Mar–21

May–21

Jul–21

Sep–21

Nov–21

Jan–22

Mar–22

May–22

Jul–22

Sep–22

Nov–22

Jan–23

Mar–23

Qantas Jetstar (Qantas) Rex Virgin Tigerair (Virgin) Bonza

Apr–23

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

In contrast to Qantas, Virgin Australia’s network reach has been relatively stable in recent months. It

serviced 62 routes in April 2023, slightly down on the number of routes it operated in 2019 prior to the

pandemic. Virgin Australia exited the Darwin – Sydney route in January, which is currently served by

Qantas and Jetstar. The airline has instead resumed its services on Hamilton Island – Melbourne, a

route it had largely stopped operating on following the pandemic.

Qantas subsidiary Jetstar operated 59 routes in April 2023, which was 1 more than in January. The

airline has resumed services on its Gold Coast – Perth route. This is a route that the airline serviced

historically, with capacity increasing signicantly over the school holiday terms around January, April,

July, and October.

30

Rex continued to serve 43 routes in April 2023, the same as in January. In recent years Rex has

expanded into 7 major intercity routes, while also withdrawing from some regional routes.

Consumers are most likely to benet through better services and more attractive pricing on routes

where there are more competing airline groups. The ACCC collects data from 4 different airline

groups: Bonza, Qantas Group (comprising Qantas and Jetstar), Rex and Virgin Australia (including

Tigerair until March 2020).

Figure 8 shows that 41% of domestic passengers ew on routes with 3 competing airline groups.

This is around 1 percentage point higher than in January following Bonza’s entry on the contested

Melbourne – Sunshine Coast route. Bonza’s entry on this route increased the number of routes with

3 competing airline groups to 8. There are no routes with 4 competing airline groups.

30 Based on data from CAPA – Centre for Aviation, accessed 25 May 2023.

18

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 8 Number of passengers on routes serviced by 1, 2 and 3 airline groups – January 2019 to

April 2023

Monthly passengers (Millions)

0

1

2

3

4

5

Jan–19

Mar–19

May–19

Jul–19

Sep–19

Nov–19

Jan–20

Mar–20

May–20

Jul–20

Sep–20

Nov–20

Jan–21

Mar–21

May–21

Jul–21

Sep–21

Nov–21

Jan–22

Mar–22

May–22

Jul–22

Sep–22

Nov–22

Jan–23

Mar–23

1 airline group 2 airline groups 3 airline groups

Apr–23

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

Note: Airline groups comprise Qantas Group (including Jetstar), Virgin Australia (including Tigerair), Rex and Bonza. There were

no routes on which all 4 airline groups offered services.

As Bonza is largely introducing previously unserved routes into the Australian market, the number of

routes serviced by a sole operator increased to 101 in April. The proportion of passengers on these

routes increased by 1 percentage point since January to 9%.

Almost half of all domestic passenger trips in April 2023 took place on routes with 2 competing

airline groups (49%, down 3 percentage points since January 2023). All of the routes with 2 airline

groups involved the Qantas Group competing with one of either Rex or Virgin Australia. This means

none of the routes had only Virgin Australia and Rex competing with one another.

Figure 9 shows that despite the expansion of Rex and the recent entry of Bonza, the market share

composition remains very highly concentrated. Over the last 12 months, the 2 largest airline groups –

Qantas Group (including Jetstar) and Virgin Australia – consistently accounted for around 95% of the

domestic passenger market. The 2 groups ew 94% of passengers in April 2023.

19

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 9 Airline passenger market shares across all domestic routes – January 2019 to April 2023

Market share (%)

Jan–19

Mar–19

May–19

Jul–19

Sep–19

Nov–19

Jan–20

Mar–20

May–20

Jul–20

Sep–20

Nov–20

Jan–21

Mar–21

May–21

Jul–21

Sep–21

Nov–21

Jan–22

Mar–22

May–22

Jul–22

Sep–22

Nov–22

Jan–23

Mar–23

Apr–23

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Qantas Jetstar (Qantas) Virgin Tigerair (Virgin) Rex Bonza

Source: Data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex and Bonza.

Qantas accounted for 36.1% of the market in April 2023. The airline’s market share has been down

slightly in 2023 from where it was for most of 2022. This partly reects seasonal trends, with

Qantas generally conceding market share to its low-cost subsidiary Jetstar during periods when

proportionally more people are ying for leisure purposes, such as January and the Easter school

holidays in April.

For these reasons, Jetstar’s market share increased in April 2023 as it carried nearly a quarter

(24.7%) of all domestic passengers. However, its April 2023 gure was 3 percentage points below the

previous April market share of 27.8% in 2022.

The combined market share for the Qantas Group was 60.8% in April 2023. Qantas Group’s market

share averaged 61.3% over the 12 months to April, which was slightly higher than its average share

in 2019.

Virgin Australia’s market share is less impacted by seasonal trends than Qantas and Jetstar. The

airline ew 33.2% of domestic passengers in April 2023, which was roughly in line with its market

share over the past year. Despite going through voluntary administration in 2020, Virgin Australia’s

market share is more than 3 percentage points above 2019 levels. As an airline group, however, its

market share has declined since that time due to the exit of its low-cost subsidiary Tigerair. Virgin

Australia maintained its lead on the larger city routes with a market share of 37.7% in April.

Rex’s market share was 4.8% in April 2023, slightly below a recent peak of 5.2% in March. Its average

market share was 4.9% for the 12 months to April.

The chart also shows new entrant and low‑cost carrier Bonza for the rst time. It ew 1.2% of

passengers in April 2023, but this should grow slightly from May which is when all of its routes

became operational.

20

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Domestic airfares have generally fallen in recent months after hitting historically high levels in

December 2022. These falls reect a number of factors including a decline in the price of jet fuel,

an easing of pent-up demand for travel, the rising cost of living becoming a greater concern for

consumers, and marginal increases to capacity.

Much of the analysis in this section uses movements of ination‑adjusted real prices. This means

the measure reects how airfares are changing relative to prices of other goods and services in the

economy. While this is the standard approach to analysing price movements over time, the high rate

of ination over the last year means there has been a growing disparity between movements in real

prices and movements in the nominal prices actually paid by consumers. The higher the ination rate,

the greater the difference in the measure of real prices compared to the measure of nominal prices.

Average revenue per passenger reects movements in airfares across all types of domestic tickets

and fare classes. Figure 10 shows that following the peak in December 2022, average revenue fell by

14% in real terms to April 2023. Average revenue per passenger in April 2023 was 2% higher than pre-

pandemic levels (April 2019) in real terms and 17% higher in nominal terms.

Figure 10 Index of average fare revenue per passenger – January 2019 to April 2023

Index (Jan 19 = 100)

Jan–19

Mar–19

May–19

Jul–19

Sep–19

Nov–19

Jan–20

Mar–20

May–20

Jul–20

Sep–20

Nov–20

Jan–21

Mar–21

May–21

Jul–21

Sep–21

Nov–21

Jan–22

Mar–22

May–22

Jul–22

Sep–22

Nov–22

Jan–23

Mar–23

Apr–23

0

20

40

60

8 0

100

120

140

160

Nominal Real

Source: ACCC calculations using data from the ABS and data collected by the ACCC from Qantas, Jetstar, Virgin Australia, Rex

and Bonza.

Note: The average revenue per passenger includes both economy and business fare revenue. It excludes ancillaries and

Tigerair data. Data has been adjusted for ination using the latest ABS CPI quarterly data up to March 2023.

Price indices calculated by the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE)

have also shown a recent fall in the real price of domestic airfares. BITRE’s indices are based on the

cheapest available fare and therefore may not represent price movements more broadly.

Figure 11 shows the price index of best discount economy airfares in May 2023 was 43% below what

it was in December 2022 and 14% less than in February 2023. Despite these recent falls, the price

index was still 13% higher in real terms (32% in nominal terms) in May 2023 compared to the same

month pre-pandemic.

21

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 11 Real price index of the best discount economy airfares – May 2019 to May 2023

Best discount Best discount (13 month moving average)

Index (July 03 = 100)

May–19

Jul–19

Sep–19

Nov–19

Jan–20

Mar–20

May–20

Jul–20

Sep–20

Nov–20

Jan–21

Mar–21

May–21

Jul–21

Sep–21

Nov–21

Jan–22

Mar–22

May–22

Jul–22

Sep–22

Nov–22

Jan–23

Mar–23

May–23

Source: BITRE Domestic Air Fares (Best Discount) index (cheapest available economy airfares). The price index is weighted

across the 70 busiest domestic routes.

Note: Grey bars indicate December and Easter holiday periods. Airfares recorded between April 2021–February 2022 may be

impacted by the government’s half-price ticket program (TANS).

This fall in best discount economy airfares was not observed across all routes collected by BITRE.

Airfares on some routes have increased and continue to be signicantly higher compared to

pre-pandemic. In particular, the cheapest return fares for Coffs Harbour – Sydney was almost triple

at $348 in May 2023. Similarly, several routes that have more than doubled include Brisbane – Darwin

(up 172% to $622) and Launceston – Sydney (up 138% to $228). Other routes where fares have

increased signicantly include Cairns – Gold Coast (up 129% to $362) and Adelaide – Brisbane (up

121% to $398).

BITRE also calculates price indices for restricted economy and business airfares, which as noted

above is derived by the lowest available fare observed by BITRE. Between December 2022 and

May 2023, both of these price indices fell by 11% in real terms. Both of these airfare types are more

than 20% lower than pre-pandemic levels in real terms.

A key reason for the falling airfares in recent months is the signicant decline in the price of jet

fuel, which is a key operating cost for airlines. Figure 12 shows that the price of jet fuel declined to

$137 per barrel in May 2023. This is a fall of almost half in real terms since the price of jet fuel hit

a record high of $259 per barrel in June 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The rening

margin between jet fuel and Brent crude oil prices has fallen by almost half from $47 per barrel in

February 2023 to $24 in May 2023. The falling price of jet fuel may enable the airlines to further

reduce airfares in the future.

22

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

Figure 12 Real jet fuel and Brent crude oil prices – January 2007 to May 2023

$A per barrel

Jet fuel Brent crude oil

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Jan–07

Jan–08

Jan–09

Jan–10

Jan–11

Jan–12

Jan–13

Jan–14

Jan–15

Jan–16

Jan–17

Jan–18

Jan–19

Jan–20

Jan–21

Jan–22

May–23

Source: ACCC calculations using ABS, RBA and US EIA data.

Note: US Gulf Coast Jet Fuel prices converted into current Australian dollar terms. The price an airline pays for jet fuel will also

vary depending on the ports to which its aircraft operate and the respective region‑specic jet fuel benchmarks. The

latest month of data is to 24 May 2023.

Very little, if any, of the recent fall in the measures of airfares used above can be explained by the

launch of low-cost airline Bonza. Bonza currently represents a very small proportion of the industry

with only a few ights per week on predominantly small routes.

23

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

4. State of competition in

domestic airline services

This chapter considers the level of competition between domestic airlines over the last 10–15 years,

and how this has impacted on consumers.

It offers the view that a lack of effective competition is a key reason why the industry has generally

underperformed in terms of meeting the needs of both the travelling public and the parts of the

economy that rely on domestic air travel.

While the expansion by Rex and the launch of Bonza provides an opportunity for the industry to move

beyond its historical duopoly market structure, both airlines would need to expand signicantly to

become meaningful competitors to the Qantas Group and Virgin Australia. The ACCC will continue to

watch how the incumbent airlines respond to this emerging competition and we will investigate where

we consider there has been a potential contravention of the competition law.

Many of the views in this chapter are explored in more detail in the ACCC’s submission in response to

the terms of reference for the Australian Government’s Aviation White Paper process.

31

The Australian domestic airline industry has long been characterised as a duopoly. Going back as far

as 2002 when Ansett Australia ceased operations, over 9 in every 10 domestic passengers on regular

scheduled ights have own with either the Qantas or Virgin Australia airline groups. This represents

an extraordinarily high level of concentration.

Data presented by the Grattan Institute in its 2017 study on competition showed that the domestic

airline industry was one of the 2 most highly concentrated sectors in the Australian economy, other

than natural monopolies.

32

The level of concentration in the domestic airlines sector was higher than

for banks, supermarkets, internet service providers, newspaper publishers and insurance companies.

The Qantas Group has been the dominant airline group over this period. The group operates a dual

brand strategy with Qantas (including QantasLink) as a full-service airline and Jetstar as a budget

leisure airline. Combined, the 2 airlines have generally accounted for approximately 60% of domestic

passengers. Further, while prots in the airline industry can uctuate greatly from year‑to‑year, the

Qantas Group earned most of the prots made by the domestic airline industry. The Qantas Group

estimates that it earned around 70% of the domestic industry prots (earnings before interest and

taxation, EBIT) between the 2011 and 2015 nancial years, which increased to around 90% between

the 2015 and 2019 nancial years.

33

The dominance of the Qantas Group derives from multiple sources. Qantas beneted from merging

with Australian Airlines in 1992, which was one of only 2 airlines (along with Ansett Australia)

permitted to operate domestic ights prior to market liberalisation in the 1990s. This legacy provided

Qantas with advantages such as the early establishment of routes as well as access to both

airport terminals and take‑off and landing slots. Qantas has also invested signicantly to develop

31 ACCC, Aviation White Paper: ACCC submission in response to the terms of reference, 15 March 2023.

32 Grattan Institute, Competition in Australia: Too little of a good thing?, December 2017, p 11.

33 Qantas, ‘Qantas Group Investor Day Presentation (2023)’, 30 May 2023, accessed 30 May 2023.

24

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

comparative advantages such as being able to offer customers the largest domestic route network,

schedule, network of airport lounges, and customer loyalty program.

There have been some periods when consumers have benetted from heightened levels of

competition. In the early 2010s, low-cost carrier Virgin Blue’s transition into full-service carrier Virgin

Australia meant that it was competing more directly with Qantas, including for the highly protable

corporate customer segment. The 2 airlines competed vigorously for market share by adding

capacity and bringing down airfares. However, the price war proved to be unsustainable and was

abandoned in the latter part of the decade after both airlines had incurred signicant nancial losses.

Another source of competition in the early 2010s was the presence of Tiger Airways. In particular, the

low-cost carrier competed with Jetstar for budget leisure travellers. This competition led to important

developments such as the Qantas Group starting to deploy Jetstar on some larger intercity routes

(alongside Qantas) to better compete with Tiger Airways. Tiger Airways’ competitive impact reduced

over time as it developed a poor reputation after it was temporarily grounded by the Civil Aviation

Safety Authority (CASA). Tiger Airways lost its independence soon after when it was acquired by

Virgin Australia (and renamed Tigerair) through transactions in 2013 and 2015.

Competition within the domestic market was relatively subdued towards the end of the 2010s and

in the lead-up to the pandemic. Qantas Group and Virgin Australia did not face any competition

from an independent airline on the major routes. Unlike the period of price wars in the earlier part of

the decade, the airlines did not compete as rigorously, both appearing content with their respective

shares of the market. In this regard, the 2 airline groups publicly talk about their target market

shares which broadly reect a 2/3 (Qantas Group) and 1/3 (Virgin Australia) split of total domestic

passengers. During the end of the 2010s, it is also likely that neither airline group felt much of a

competitive constraint from the potential for a new airline to enter the market, with Tiger Airways the

last to do this in 2007 (until Bonza in 2023).

There have been signicant competitive developments within the industry since the pandemic. One

of the rst key structural shifts for the industry was the decision by Virgin Australia to suspend the

operations of Tigerair in March 2020. While the suspension was temporary at the time, the airline

was formally discontinued in September 2020, leaving Jetstar as the country’s only budget airline at

the time.

In what represented a substantial risk to Australian domestic airline competition, Virgin Australia

then went into voluntary administration in April 2020 with signicant levels of debt. Virgin Australia

emerged from administration in November 2020 with new owner Bain Capital and a new strategy

targeting ‘value-conscious’ travellers in the middle of the market. New CEO Jayne Hrdlicka said at

the time that ‘Australia already has a low-cost carrier and a traditional full-service airline, and we

won’t be either’.

34

Virgin Australia also consolidated its eet to the one aircraft type (Boeing 737s) and

ooaded other aircraft types.

The new strategy employed by Virgin Australia has had several consequences for competition. While

Virgin Australia continues to seek to attract business travellers, its new offering based around lower

airfares but without complimentary meals has likely meant that Qantas faces less direct competition

in the premium corporate customer segment. Separately, with a less diverse eet of aircraft, Virgin

Australia is less capable of directly servicing certain routes, especially in regional areas. Virgin

Australia continues to offer some of these routes through the wet leasing of aircraft through Alliance

Airlines and Link Airways.

34 Virgin Australia, Ready for take-off: Virgin Australia Group soars out of administration, unveils future direction, [media release],

18 November 2020, accessed 29 May 2023.

25

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

By the end of 2022, 2 years after emerging from voluntary administration, Virgin Australia said that

its business transformation was returning the airline to protability and enabled it to increase its eet

size by over 60%.

35

Other competitive developments since the pandemic have been the expansion by regional airline

Rex onto major intercity routes in 2021 and the launch of low-cost airline Bonza in 2023. These

developments are discussed in section 4.3.

With a highly concentrated industry structure and signicant barriers to entry and expansion holding

back competition, it is not surprising that many of the outcomes from the domestic airline industry

for consumers and the broader economy have been underwhelming.

‘Competition’ encompasses a range of factors and market dynamics beyond providing connectivity

between destinations. Without the risk of losing customers to other airlines, there is less incentive for

airlines to offer attractive airfares, develop more direct routes, operate reliable services, and invest in

systems to better deal with customer concerns.

Figure 13 shows movement in price indices produced by BITRE for different types of tickets. Between

January 2013 and January 2020, prior to pandemic, the price index for restricted economy airfares

went up by 41% in real terms and the price index for business class tickets went up by 26%. The

discount economy index increased by 3% over this period.

Figure 13 Real movements in domestic Australian airfares (13-month moving average) – January 2013 to

May 2023

Index (July 03 = 100)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Business Class Restricted Economy Best Discount

May–23

Jan–13

Jun–13

Nov–13

Apr–14

Sep–14

Feb–15

Jul–15

Dec–15

May–16

Oct–16

Mar–17

Aug–17

Jan–18

Jun–18

Nov–18

Apr–19

Sep–19

Feb–20

Jul–20

Dec–20

May–21

Oct–21

Mar–22

Aug–22

Jan–23

Source: BITRE monthly survey of the lowest available fare in each fare class, weighted over selected routes.

Note: Adjusted for CPI. The sharp increase in the restricted economy index from November 2017 is due to the exclusion from

the index of Jetstar’s restricted economy product (Starter with Max) after the airline began refunding cancellations in the

form of a voucher.

Airfares initially fell following the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, but they began increasing again when

airlines returned to more normal levels of ying in 2022. As discussed in section 3.6, the discounted

35 Virgin Australia, Bring on Wonderful: Virgin Australia soars through transformation, enters wonderful era of ying [media

release], 24 October 2022, accessed 18 May 2023.

26

ACCC | Airline competition in Australia | Final report

economy price index hit record highs in late 2022 before falling again throughout 2023. The restricted

economy and business indices remain below pre-pandemic levels in May 2023.

Over the past decade, domestic ights have also become less reliable in terms of whether a ight

will go ahead and whether it will arrive on-time (Figure 14). Even now that the industry has had some

time to return to normal operations after the COVID‑19 related travel restrictions, 3.9% of ights

were cancelled and 28.2% of ights arrived late in April 2023. Even prior to the pandemic, the rate of

delayed arrivals had trended up to over 1 in every 4 ights by December 2019. Some of this trend may

be explained by growing airport congestion.

Figure 14 Rate of domestic delayed arrivals and ight cancellations – January 2013 to April 2023

Apr–23

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Jan–13

Jun–13

Nov–13

Apr–14

Sep–14

Feb–15

Jul–15

Dec–15

May–16

Oct–16

Mar–17

Aug–17

Jan–18

Jun–18

Nov–18

Apr–19

Sep–19

Feb–20

Jul–20

Dec–20

May–21

Oct–21

Mar–22

Aug–22

Jan–23

Delayed arrivals Cancellations

Rate (%)

Source: BITRE on-time performance time series – April 2023.

Note: A ight is regarded as a cancellation if it is cancelled or rescheduled less than 7 days prior to its scheduled departure

time. A ight is considered delayed if it arrives more than 15 minutes after the scheduled arrival time shown on the

airline’s schedule.

Airlines have also been providing a declining level of customer service. Even accounting for the

disruption to the airline industry from the pandemic, consumer dissatisfaction with the airline industry

has been rising over the years. As noted in our submission to the Aviation White Paper process,

contacts to the ACCC about the airlines have been trending upwards since January 2018, particularly

in 2022 following pandemic related travel restrictions and lockdowns being lifted.

36

The CEO of Bonza, Tim Jordan, considers that Australian consumers have missed out because of

a lack of competition in the market. In May 2022 Jordan said that despite having the eighth largest