143

JESSE ROTHSTEIN

University of California, Berkeley

Unemployment Insurance and

Job Search in the Great Recession

ABSTRACT More than 2 years after the official end of the Great Reces-

sion, the labor market remains historically weak. One candidate explanation

is supply-side effects driven by dramatic expansions of unemployment insur-

ance (UI) benefit durations, to as long as 99 weeks. This paper investigates

the effect of these extensions on job search and reemployment. I use the lon-

gitudinal structure of the Current Population Survey to construct unemploy-

ment exit hazards that vary across states, over time, and between individuals

with differing unemployment durations. I then use these hazards to explore

a variety of comparisons intended to distinguish the effects of UI extensions

from other determinants of employment outcomes. The various specifications

yield quite similar results. UI extensions had significant but small negative

effects on the probability that the eligible unemployed would exit unemploy-

ment. These effects are concentrated among the long-term unemployed. The

estimates imply that UI extensions raised the unemployment rate in early 2011

by only about 0.1 to 0.5 percentage point, much less than implied by previous

analyses, with at least half of this effect attributable to reduced labor force exit

among the unemployed rather than to the changes in reemployment rates that

are of greater policy concern.

A

lthough the so-called Great Recession officially ended in June 2009,

the labor market remains stagnant. In November 2011 the unemploy-

ment rate was 8.6 percent, only the third time in 2.5 years that it was below

9 percent. Nearly 45 percent of the unemployed had been out of work for

more than 6 months.

An important part of the policy response to the Great Recession has been

a dramatic expansion of unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. Preexist-

ing law provided for up to 26 weeks of benefits, plus up to 20 additional

weeks under the Extended Benefits (EB) program in states experiencing

high unemployment rates. But in past recessions Congress has frequently

144 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

authorized additional weeks on an ad hoc basis, and in June 2008 it enacted

the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, which, in

a series of extensions, has brought statutory benefit durations to as long as

99 weeks.

Unemployment benefits subsidize continued unemployment. Thus, it

seems likely that the unprecedented UI extensions have contributed to

some degree to the elevated unemployment rate. However, the magnitude

and interpretation of this effect are not clear. Several recent analyses have

found that the extensions contributed around 1.0 percentage point to the

unemployment rate in 2010 and early 2011 (see, for example, Mazumder

2011, Valletta and Kuang 2010, Fujita 2011), and some observers have

claimed that the effects were several times that size.

1

There are two channels by which UI can raise unemployment, with very

different policy implications (Solon 1979). On the one hand, UI benefits

can lead recipients to reduce their search effort and raise their reservation

wage, slowing the transition into employment. On the other hand, these

benefits, which are available only to those engaged in active job search,

provide an incentive for continued search for those who might otherwise

exit the labor force. This second channel raises measured unemployment

but does not reduce the reemployment of displaced workers. Partly on the

basis of this observation, David Howell and Bert Azizoglu (2011) find “no

support” for the view that the recent UI extensions reduced employment.

Unfortunately, most studies of the effect of UI on the duration of unem-

ployment have been unable to distinguish the two channels.

Determining the portion of any rise in unemployment attributable to UI

extensions on labor market outcomes is difficult because these extensions

are endogenous by design. UI benefits are extended in severe recessions

precisely because it is seen as unreasonable to demand that workers find

jobs quickly when the labor market is weak. Thus, obtaining a credible

estimate of the effect of the recent UI extensions requires a strategy for

distinguishing this effect from the confounding influence of historically

weak labor demand.

This paper uses the haphazard rollout of the EUC and EB programs dur-

ing the Great Recession and its aftermath to identify the partial equilibrium

effects of the recent UI extensions on the labor market outcomes of work-

ers who have lost their jobs and are actively seeking new employment.

I use the longitudinal structure of the Current Population Survey (CPS) to

1. Grubb (2011); Robert Barro, “The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment,” Wall Street

Journal, August 30, 2010.

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 145

2. In addition, UI may reduce hysteresis by increasing labor force attachment and

thereby slowing the deterioration of job skills. If so, UI extensions could make displaced

workers more employable when demand recovers. A related possibility is that UI extensions

deter displaced workers from claiming disability payments (Duggan and Imberman 2009,

Joint Economic Committee 2010).

construct hazard rates for unemployment exit, reemployment, and labor

force exit that vary across states, over time, and between individuals enter-

ing unemployment at different dates.

I explore a variety of strategies for isolating the effects of UI exten-

sions. One strategy exploits the gradual rollout and repeated expiration of

EUC benefits through successive federal legislation to generate variation

in benefit durations across labor markets facing plausibly similar demand

conditions. Second, following a recent study by Rob Valletta and Kath-

erine Kuang (2010), I use UI-ineligible job seekers as a control group for

eligible unemployed workers in the same state and month. A third strategy

exploits decisions by individual states to take up or decline optional EB

provisions that alter the availability of benefits; this strategy uses a “con-

trol function” to distinguish the effects of the economic conditions that

define eligibility. Finally, I exploit differences in remaining benefit eligibil-

ity among UI-eligible workers displaced at different times, but searching

for work in the same labor markets, to identify the effect of approaching

benefit exhaustion.

All of the strategies point to broadly similar conclusions. The availabil-

ity of extended UI benefits (under both EB and EUC) caused small reduc-

tions in the probability that an unemployed worker exited unemployment,

reducing the monthly hazard in the fourth quarter of 2010, when the aver-

age unemployed worker anticipated a total benefit duration of 65 weeks, by

between 1 and 3 percentage points on a base of 22.4 percent. Not more than

half of this unemployment exit effect comes from effects on reemployment:

my preferred specification indicates that UI extensions reduced the average

monthly reemployment hazard of unemployed job losers in 2010Q4 by

0.5 percentage point (on a base of 13.4 percent) and reduced the monthly

labor force exit hazard by 1.0 percentage point (on a base of 9.0 percent).

The labor force exit effect raises the possibility that UI extensions

actually raise the reemployment rate of those who lose their jobs in bad

economic times, by extending the time until they abandon their search.

2

However, estimating this effect requires strong assumptions, along with

ad hoc corrections for shortcomings in the data. Using such assumptions

and corrections, I simulate the effect of the 2008–10 UI extensions on

aggregate unemployment and on the fraction of unemployed workers out of

146 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

work 27 weeks or more (the long-term unemployment share). All of the esti-

mates are of partial equilibrium effects, as I ignore any effects of reduced

job search by one worker on others’ search behavior or job finding rates.

This almost certainly leads me to overstate the effect of UI extensions.

Nevertheless, I find quite small effects. My preferred specification

indicates that in the absence of UI extensions, the unemployment rate in

December 2010 would have been about 0.2 percentage point lower, and

the long-term unemployment share would have been about 1.6 percentage

points lower. Even the specification yielding the largest effects indicates

that UI extensions contributed only 0.5 percentage point to the unemploy-

ment rate. Moreover, simulations that include only the labor force partici-

pation effects yield estimates at least half as large as do simulations with

both participation and reemployment effects, suggesting that reduced job

search due to UI extensions raised the unemployment rate by only 0.1 to

0.2 percentage point.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section I reviews

recent labor market trends and discusses the UI extensions that have been

an important part of the policy response. It also presents a simple model

of the effects of UI benefit durations and reviews existing estimates of

the effect of the recent extensions. Section II discusses the longitudi-

nally linked CPS data that I use to study the effects of the UI extensions.

Section III presents my empirical strategies for isolating these effects.

Section IV reports estimates of the effect of UI benefit durations on the

unemployment exit hazard. Section V develops a simulation methodol-

ogy that I use to extrapolate these estimates to obtain effects on labor

market aggregates, and presents results. Section VI concludes.

I. The Labor Market and Unemployment Insurance

in the Great Recession

The Great Recession officially began in December 2007, but the downturn

was slow at first: seasonally adjusted real GDP fell at an annual rate of only

1.8 percent in the first quarter of 2008, then grew at a 1.3 percent rate in the

second quarter. Conditions then worsened sharply, and GDP contracted at

an annual rate of 8.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008.

I.A. Labor Market Trends

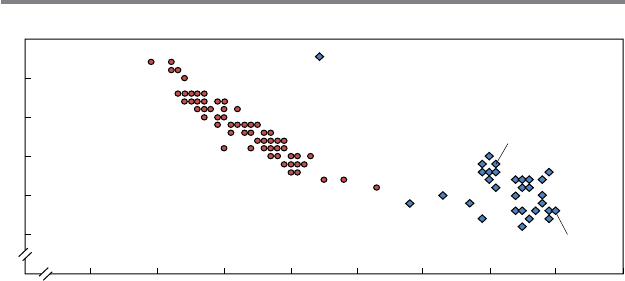

The labor market downturn also began slowly. Figure 1 shows that

the unemployment rate began trending up in 2007, but it remained only

5.8 percent as of July 2008. Over the next year, however, it rose 3.7 per-

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 147

centage points, to 9.5 percent, and it has fallen below 9 percent in only

three months since. Employment data show similar trends: nonfarm payroll

employment rose through most of 2007, fell by 738,000 in the first half

of 2008, and then fell by nearly 6.8 million over the next 12 months. Job

losses continued at slower rates in the second half of 2009, followed by

modest and inconsistent growth in 2010. As of August 2011, employment

remained 6.9 million below its prerecession peak.

Figure 1 also shows the long-term unemployment share. This measure

has lagged the overall unemployment rate by about 6 months or perhaps a

bit more: it began to increase slowly in early 2008 and much more quickly

in late 2008, reaching a peak of around 45 percent in early 2010—nearly

20 percentage points higher than the previous record of 26.0 percent,

recorded in June 1983—and remaining mostly stable since then.

Figure 2 illustrates gross labor market flows during and after the reces-

sion. These are obtained from two sources: the Job Openings and Labor

Turnover Survey (JOLTS), which derives from employer reports, and the

Long-term unemployment share

b

(right scale)

Unemployment rate

(left scale)

Percent Percent

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

20

30

40

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

a. Both series are seasonally adjusted monthly data.

b. Fraction of the unemployed who have been out of work 27 weeks or longer.

Figure 1. Unemployment and Long-Term Unemployment, 2004–11

a

148 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

2004 2011

5

4

3

2

1

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

a. All series are seasonally adjusted monthly data, smoothed with a 3-month symmetric triangular

moving average, y

t

sm

= (y

t–1

+ 2y

t

+ y

t+1

)/4.

b. From the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey data, which derive from employer surveys.

c. From the research series on labor force status flows constructed by the BLS from longitudinally

linked monthly CPS files.

Millions

Millions Percent of previous month’s unemployed

Flows out of jobs

Flows into jobs and out of unemployment

Quits

b

Layoffs and discharges

b

E-U flows

c

Hires

b

(left scale)

U-E flow rate

c

(right scale)

U-N flow rate

c

(right scale)

Figure 2. Gross Labor Market Flows, 2004–11

a

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 149

3. See Elsby, Hobijn, and ¸S ahin (2010) for a more detailed examination of these and

other aggregate data.

gross flows research series computed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

from matched monthly CPS household data, discussed at length below.

The top panel shows flows out of work: quits and layoffs from the JOLTS

(“other separations,” including retirements, are not shown), and gross flows

from employment to unemployment (E-U) from the CPS. The bottom

panel shows flows into work: hires from the JOLTS and unemployment-

to-employment (U-E) flows from the CPS. It also shows unemployment-

to-nonparticipation (U-N) flows; both the U-E and the U-N flows are

expressed as shares of the previous month’s unemployed population.

The two panels of figure 2 shed a good deal of light on the dynamics

of the rise and stagnation of the unemployment rate.

3

The top panel shows

that layoffs spiked and quits collapsed in late 2008, indicating an extreme

weakening of labor demand; interestingly, the decline in quits seems to

have preceded the increase in layoffs by several months. Not surprisingly,

the number of monthly E-U transitions increased by about one-third over

the course of 2008. Layoffs returned to (or even below) normal levels in

late 2009, but quits remained just over half of their prerecession level and

E-U flows remained high, suggesting that weak demand continued to dis-

suade workers from leaving their jobs and to impede the usual quick transi-

tion of laid-off workers into new jobs.

The bottom panel of figure 2 shows that the collapse in new hires was

more gradual than the spike in layoffs and began much earlier, in late 2007.

The rate at which unemployed workers transitioned into employment also

began to decline at this time, then fell much more sharply in late 2008.

Recall that the rapid run-up in long-term unemployment was in mid-2009,

roughly 6 months later, again suggesting that the usual process by which

job losers are recycled into new jobs was substantially disrupted around

the time of the financial crisis. U-E flows remain very low at this writ-

ing. Finally, the U-N flow rate fell rather than rose during the recession,

despite weak labor demand that might plausibly have led unemployed

workers to become discouraged. This is plausibly a consequence of UI

benefit extensions, which created incentives for ongoing search even if the

prospect of finding a job was remote.

I.B. The Policy Response

Congress responded quickly to the deteriorating labor market, autho-

rizing the EUC program in June 2008, but proceeded in fits and starts

150 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

4. This discussion draws heavily on Fujita (2010). I neglect a number of details of the UI

program rules. In particular, claimants whose tenure in their previous job was short are not

eligible for the full 26 weeks of regular benefits.

thereafter.

4

The June 2008 legislation made 13 weeks of EUC benefits

available to anyone who exhausted regular benefits before March 28,

2009. The program was subsequently expanded in November 2008. That

expansion extended the original EUC (now called EUC tier I) benefits to

20 weeks and added a second tier of 13 weeks of benefits in states with

unemployment rates above 6 percent. A second expansion in November

2009 changed tier II benefits to 14 weeks and added tier III, 13 weeks of

benefits in states with unemployment rates above 6 percent, and tier IV,

an additional 6 weeks in states with unemployment rates above 8.5 per-

cent. Individuals in states qualifying for all four tiers were thus eligible for

53 weeks of EUC benefits. The first four columns of table 1 show the num-

ber of tiers and number of weeks available over time.

The EUC program was originally set to expire on March 28, 2009. How-

ever, the program was reauthorized several times to delay the scheduled

Table 1. Changes in the Emergency Unemployment Compensation Program over

2008–10

Weeks of benefits available under EUC tier

Scheduled EUC

expirationDate

a

I II III

b

IV

c

Jun. 30, 2008 13 Mar. 28, 2009

Nov. 21, 2008 20 13

b

Mar. 28, 2009

Feb. 17, 2009 20 13

b

Dec. 26, 2009

Nov. 6, 2009 20 14 13 6 Dec. 26, 2009

Dec. 19, 2009 20 14 13 6 Feb. 28, 2010

Feb. 28, 2010 0 0 0 0 NA

Mar. 2, 2010 20 14 13 6 Apr. 5, 2010

Apr. 5, 2010 0 0 0 0 NA

Apr. 15, 2010 20 14 13 6 Jun. 2, 2010

Jun. 2, 2010 0 0 0 0 NA

Jul. 22, 2010 20 14 13 6 Nov. 30, 2010

Nov. 30, 2010 0 0 0 0 NA

Dec. 17, 2010 20 14 13 6 Jan. 3, 2012

Dec. 23, 2011 20 14 13 6 Mar. 6, 2012

d

Source: Fujita (2010) and Department of Labor bulletins.

a. Dates on which legislation creating, changing, or reauthorizing the program was enacted or the

program expired. After each expiration, the eventual reauthorization was retroactive. NA = not applicable.

b. Benefits available only in states with unemployment rates above 6 percent.

c. Benefits available only in states with unemployment rates above 8.5 percent.

d. As this volume goes to press.

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 151

5. The Recovery Act also provided for tax deductibility of a portion of UI benefits, for

somewhat expanded eligibility, and for more generous weekly benefit amounts.

6. During the period covered by my sample, the minimal triggers provided benefits only

when the 13-week moving average of the insured unemployment rate (IUR) was at least

5 percent and above 120 percent of the maximum of its values 1 year and 2 years earlier. It

is this lookback period that accounts for the decline in the minimal series in late 2009. The

maximal triggers also provided benefits in states with 13-week IURs above 6 percent (regard-

less of their lagged values) or with a 3-month moving average total unemployment rate (the

traditional measure) above 6.5 percent and above 110 percent of the value either 1 or 2 years

earlier. Each simulated benefits series allows a state’s status to change no more than once in

13 weeks, following program rules; the maximal series also assumes that the optional 3-year

lookback was adopted when it became available in 2011. See National Employment Law

Project (2011) and the Federal-State Extended Unemployment Compensation Act of 1970

(workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/EB_law_for_web.pdf, accessed June 28, 2011).

expiration. The last column of table 1 shows the scheduled expiration date

as it changed over time. For much of the program’s history, the expira-

tion date was quite close. Indeed, on three occasions, in April, June, and

November 2010, Congress allowed the program to expire. Each time, Con-

gress eventually reauthorized it retroactive to the previous expiration date,

but following the June expiration this took 7 weeks.

The EUC program complemented a preexisting program, the EB pro-

gram, which allowed for 13 or 20 weeks of extra benefits in states with ele-

vated unemployment rates. EB is an optional program: participating states

can choose among several options regarding the specific triggers that will

activate benefits. As costs are traditionally split evenly between the state and

the federal government, many states have opted not to participate or have

chosen relatively stringent triggers. However, the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act of 2009, enacted in February of that year, provided for

full federal funding of benefits under EB. This induced a number of states

to begin participating in the program and to adopt more generous triggers.

5

Figure 3 shows the number of states in which benefits under the EB

program have been available over time, along with simulated counts of the

number of states where benefits would have been available had every state

adopted minimal or maximal triggers. At the beginning of 2009, only three

states offered benefits under this program, but by July of that year benefits

were available in 35 states. Figure 3 shows that this change reflected a com-

bination of increased EB participation, which brought the actual series well

above the minimal series, and deteriorating economic conditions, which

would have expanded EB participation even if states had not changed their

trigger choices.

6

The figure also shows that participation plummeted each

time the EUC program was allowed to expire: a number of states wrote

152 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

their EB implementing legislation to provide for state participation only as

long as the federal government paid 100 percent of the cost, and this provi-

sion expired and was reauthorized each time along with the EUC program.

Other than these spikes, participation has been relatively stable over time.

A final feature of figure 3 is the wide disparity between the simulated

minimal and maximal series: relatively few states, and none after mid-

2010, qualified for benefits under the least generous triggers, but nearly

all states did so under the most generous options. Thus, Alabama and Mis-

sissippi, each with January 2010 total unemployment rates of 10.4 percent

but insured unemployment rates below 4 percent, both qualified under the

2008 2009 2010 2011

10

20

30

40

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the BLS and the Employment and Training Administration.

a. Computed from the Employment and Training Administration’s weekly EB trigger notices.

b. Simulated for a state that has adopted all three of the following: the alternative insured unemploy-

ment rate (IUR) trigger, which provides EB if the IUR is above 6 percent, regardless of its lagged values;

the optional total unemployment rate (TUR) trigger, which provides EB if the TUR exceeds 6.5 percent

and is above the lowest of the 1-year, 2-year, or (optionally) 3-year lagged TURs; and the 3-year lookback

enacted in December 2010 (assumed to have gone into effect on January 1, 2011).

c. Series is simulated for a state that participates in the EB program but does not adopt the optional

3-year lookback period or any of the optional triggers available under the EB legislation. In such a state,

eligibility for EB depends on having an IUR that exceeds 5 percent and is above 120 percent of the higher

of the 1-year-lagged or the 2-year-lagged IUR.

No. of participating states

With maximal laws

b

Actual

a

With minimal laws

c

Figure 3. Extended Benefits Availability and the Role of Optional Triggers, 2008–11

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 153

maximal triggers but not under the minimal triggers; because Alabama had

adopted the most generous optional triggers but Mississippi had not, unem-

ployed individuals in Alabama were eligible for 20 weeks of EB but those

in Mississippi were ineligible.

When regular (26 weeks), EUC (as many as 53 weeks), and EB program

benefits (as many as 20 weeks) are combined, statutory benefit durations

have reached as long as 99 weeks in many states. However, this overstates

the number of weeks that any individual claimant could expect. According

to EUC program rules, after the program expires, participants can draw

out the remaining benefits from any tier already started but cannot transi-

tion to the next tier. Throughout 2010, the expiration date of the program

was never more than a few months away. Thus, no individual exhausting

regular benefits in 2010 could have anticipated being able to draw benefits

from EUC tiers III or IV absent further congressional action.

It is not clear how to model UI recipients’ expectations in the weeks

leading up to a scheduled EUC expiration. Recipients might reasonably

have expected an extension, if only to smooth the “cliff” in benefits that

would otherwise be created. However, each extension has been highly con-

troversial, facing determined opposition and filibusters in the Senate. It

would have been quite a leap of faith in mid-2010, in the midst of a Repub-

lican resurgence, for an unemployed worker to assume that the program

would be extended beyond its November 30 expiration. Moreover, even a

worker who foresaw an eventual extension might (correctly) have expected

a gap in benefits between the program’s expiration and its eventual reau-

thorization. For a UI recipient facing binding credit constraints, benefits

paid retroactively are much less valuable than those paid on time.

Figure 4 provides two ways of looking at the changes in UI benefit dura-

tions over time. The top panel shows estimates for the state with the longest

benefit durations at any point in time. After late 2008, this is a state qualify-

ing for 20 weeks of EB program benefits and all extant EUC tiers. The bot-

tom panel shows the (unweighted) average across states. Each panel shows

the maximum number of weeks available by statute over time, as well as

the expectations of a worker just entering unemployment and of a worker

who has just exhausted regular benefits, under the assumption that workers

do not anticipate future EUC extensions or trigger events.

The statutory series shows a rapid run-up, due primarily to EUC expan-

sions and secondarily to EB triggers, in 2008 and throughout 2009, fol-

lowed by repeated collapses in 2010 when the EUC program temporarily

expired. However, the other two series, adopting the perspectives of indi-

viduals early in their allowed benefits, show much more gradual changes.

154 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

0

26

39

52

66

79

99

0

26

39

52

66

79

99

Expected duration

at 0 weeks

b

State with maximum benefit duration

a

Weeks

Weeks

Average state

c

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the Employment and Training Administration.

a. State with the highest statutory benefit duration in a given week.

b. Expected durations are those of a UI benefit recipient at the start of (“0 weeks”) or at exhaustion of

(“26 weeks”) regular UI benefits who does not anticipate further federal legislative changes, changes in

the state’s EB program participation (including those determined by already-legislated triggers), or state

trigger events.

c. Unweighted mean across states.

Statutory duration

Expected duration

at 26 weeks

b

Expected duration

at 0 weeks

b

Statutory duration

Expected duration

at 26 weeks

b

2008

2009

2010

2011

2008

2009

2010

2011

Figure 4. UI Benefit Durations, Statutory and as Perceived by Recipients, 2008–11

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 155

7. Chetty (2008) finds that much of the search effect of UI is concentrated among those

who are credit constrained, and that lump-sum severance pay has an effect similar to that of

UI benefit extensions (see also Card, Chetty, and Weber 2007a).

Newly unemployed workers who did not expect further legislative action

would have seen the EUC program as largely irrelevant for most of its exis-

tence, because only on three occasions (roughly, the third quarter of 2008,

the second quarter of 2009, and the period since December 2010) was the

program’s expiration further away than the 26 weeks it would take for such

a worker to exhaust regular benefits. Workers just exhausting their regular

benefits, by contrast, would have anticipated at least tier I benefits at all

times except during the temporary sunsets. Even these workers, however,

could not have looked forward to tier II, III, or IV benefits for most of the

history of the program. Only in December 2010 and at the very beginning

of 2011 could any such worker have anticipated eligibility for tier IV ben-

efits. A final feature to notice is that the average state was quite close to the

maximum from 2009 on, as most states had adopted at least one of the EB

options, and most had hit their triggers.

I.C. A Model of Job Search and UI Durations

To fix ideas, I develop a simple discrete time model of job search with

exogenous wages and time-limited UI. The model yields two main results.

First, search intensity rises as UI benefit expiration approaches, and it is

higher for UI exhaustees than for those still receiving benefits. Thus, an

extension of UI benefits reduces the reemployment chances of searching

individuals, both those who have exhausted their regular benefits and those

who are still drawing regular benefits and thus not directly affected by the

extension. Second, when UI benefit receipt is conditioned on continuing

job search, benefit extensions can raise the probability of search continua-

tion. Both results imply positive effects of benefit extensions on measured

unemployment. However, because the second channel can increase search,

the net effect on the reemployment of displaced workers is ambiguous.

I assume that individuals cannot borrow or save.

7

The income and there-

fore the consumption of an unemployed individual is y

0

if she does not

receive UI benefits and y

0

+ b if she does. Her per-period flow utility is

u(c) - s, where c is her consumption and s is the amount of effort she

devotes to search. If she finds a job, it will be permanent and will offer an

exogenous wage w > y

0

+ b and flow utility u(w). The probability that she

finds a job in a given period is an increasing function of search effort, p(s),

with p′(s) > 0, p″(s) < 0, p(0) = 0, p′(0) = ∞, and p(s) < 1 for all s. Although

156 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

8. Once benefits are exhausted (d = 0), the problem becomes stationary: V

U

(0) = max

s0

u(y

0

) - s

0

+ d[p(s

0

)V

E

+ (1 - p(s

0

))V

U

(0)].

9. For example, this holds under the parameters considered by Chetty (2008, p. 8), which

in my notation correspond to constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) utility

uc

c

(

)

=

-

-

1

1

g

g

,

with g = 1.75, y

0

= 0.25w, b = 0.5w, p(s) = 0.25s

0.9

, d = 1, and V

E

= 500u(w).

p(s) might naturally be modeled as a function of changing labor market

conditions, to avoid excessive complexity from dynamic anticipation

effects I assume that job seekers treat it as fixed. I assume that unemploy-

ment benefits are available for up to D periods of unemployment. Initially,

I model these benefits as conditional only on continued unemployment;

later, I condition also on a minimum level of search effort.

These assumptions lead to a dynamic decision problem with state vari-

able d corresponding to the number of weeks of benefits remaining. Let

V

U

(d) represent the value function of an unemployed individual with d > 0

weeks of benefits remaining. The Bellman equation is

() max

11

0

Vd uy bs ps Vps

U

s

ddEd

d

()

=+

()

-+

()

+-

()()

d VVd

U

-

()

[]

1,

where s

d

represents the chosen search effort, V

E

is the value function of an

employed worker, and 1 - d is the per-week discount rate.

8

The first-order condition then implies that the choice of search effort

satisfies

′

()

=

--

()()

ps

VVd

d

EU

1

1d

for d ≥ 1. The following results are proved in the appendix.

Proposition 1. The value function V

U

(d) is increasing in d: V

U

(d + 1) >

V

U

(d) for all d ≥ 0.

Proposition 2. Search effort increases as benefit exhaustion approaches,

reaching its final level in the penultimate period of benefit receipt: s

d+1

<

s

d

< s

1

= s

0

for all d ≥ 2.

Proposition 2 implies that UI extensions will reduce job finding rates at

all unemployment durations below the new maximum benefit duration D and

will shift the time-until-reemployment distribution rightward. The relative

magnitude of the effect at different unemployment durations depends on the

shape of the p() function, but under plausible parameterizations, (s

d-1

- s

d

)

declines with d, so benefit extensions will have the largest effects on the

search effort of those who would otherwise be at or near benefit exhaustion.

9

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 157

These results neglect the impact of UI job search requirements. To incor-

porate them, I assume that an individual is considered a part of the labor force

and therefore eligible to receive UI benefits only if his search effort is at least

q > 0. Those who choose lower search effort receive no benefit payments

but preserve their benefit entitlements (that is, d is not decremented). The

Bellman equation for an individual with d > 0 weeks remaining is now

() max2

1

0

%

Vd

uy bs ps Vps

U

s

ddEd

d

()

=

+

()

-+

()

+-

()(

d

))

-

()

≥

()

-+

()

+-

%

Vd

s

uy spsV ps

U

d

ddE

1

1

0

if q

d

ddU

d

Vd

s

()()()

<

%

if q.

Unemployment benefits may deter an unemployed individual from

exiting the labor force if search productivity is low—that is, if p′q <

1

1d VVd

EU

--

()

[]

—and if benefit levels are high relative to q. It can be

shown that:

Proposition 3. Any individual who chooses search effort s ≥ q with

d weeks of benefits remaining would also choose s ≥ q with d′ weeks

remaining, for all d, d′ > 0.

Intuitively, an individual who chooses s < q when her UI entitlement has

not yet been exhausted does not use any of her remaining entitlement, so

the state variable, and therefore the optimization problem, is the same the

following week. She will thus never choose s > q again. This then implies

that the value of the state variable was irrelevant the previous week, as

remaining benefit eligibility has no effect on someone who will never

again draw benefits. The only temporally consistent strategies are to exit

the labor force immediately after a job loss or to remain in the labor force

at least until benefits are exhausted.

UI benefit extensions thus reduce nonparticipation by delaying the exit

of those who plan to exit when d reaches zero. This implies that the net

effect of UI extensions is ambiguous when job search requirements are

enforced: those who would have searched intensively will reduce their

search effort, while some of those who would have dropped out of the labor

force will increase their effort. The relative strength of these two effects is

likely to vary over the business cycle: when labor demand is strong and

search productivity therefore high, the former is likely to dominate, but

when search productivity is low, the latter may be more important.

158 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

10. Aaronson, Mazumder, and Schechter (2010), Fujita (2010), and Elsby and others

(2010) use similar strategies and obtain similar results.

Finally, two important factors not captured by this model are worth men-

tioning. First, p(s) may vary over the business cycle. If p(s) is temporarily

low but expected to recover later, UI extensions might keep individu-

als searching through the low-demand period. If search productivity is

increasing in past search effort, as implied by many discussions of hyster-

esis, this could lead to higher employment when the economy recovers.

Even without state dependence in p(s), UI extensions may bring dis-

couraged workers back into the labor force earlier in the business cycle

upswing. Second, I do not model search externalities. In reality, reduced

search effort by one person likely increases the productivity of search

for all others: if a UI recipient does not take an available job, this merely

makes the job available to someone else. This consideration is particu-

larly important if the labor market is demand constrained, but it arises

whenever labor demand is downward sloping. In the presence of search

externalities, partial equilibrium estimates of the effect of UI extensions

on recipients’ reemployment probabilities will overstate the aggregate

effects.

I.D. Earlier Estimates of the Effect of UI Extensions

in the Great Recession

A number of studies have estimated the effect of the recent UI exten-

sions on labor market outcomes. Nearly all involve extrapolations from

prerecession estimates of the effect of UI benefit durations or from pre-

recession unemployment exit rates.

Bhashkar Mazumder (2011) uses estimates of the effect of UI dura-

tions from Lawrence Katz and Bruce Meyer (1990a) and David Card and

Philip Levine (2000) to conclude that UI extensions contributed 0.8 to

1.2 percentage points to the unemployment rate in February 2011.

10

But UI

durations in the Great Recession and its aftermath have been longer and

labor market conditions have been different in a variety of ways than in

the periods examined by the earlier studies. The effect of UI durations in the

earlier estimates largely reflects a spike in the unemployment exit hazard in

the weeks immediately before benefit exhaustion. Katz and Meyer (1990b)

find that much of this spike is attributable to laid-off workers being recalled

to their previous job; these recalls are thought to have become much less

common in recent years. Card, Raj Chetty, and Andrea Weber (2007a, 2007b)

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 159

11. Another potential explanation for large spikes in at least some of the earlier studies

is so-called heaping in reported unemployment durations: improbably large numbers of

observations occur at certain durations. Katz (1986) and Sider (1985) suggest that in retro-

spective reports, much of the observed heaping—which is especially prominent at 26 weeks

(6 months), the maximum duration of regular UI benefits—reflects recall error or other fac-

tors (Card and Levine 2000) rather than UI effects.

suggest that much of the remaining spike is attributable to labor force exit

rather than reemployment, highlighting the importance of distinguishing

these two channels.

11

Shigeru Fujita (2011) extrapolates from reemployment and labor

force exit hazards observed in 2004–07 to infer counterfactual hazards in

2009–10 had UI benefits not been extended. To absorb confounding effects

from changes in labor demand, he controls linearly for the job vacancy

rate. He finds larger effects of UI extensions on unemployment than does

Mazumder (2011), primarily attributable to reduced reemployment rather

than reduced labor force exit. However, these conclusions are based on the

extrapolated effects of a reduction in the job vacancy rate that is roughly

twice as large as the range observed in the earlier period.

Mary Daly, Bart Hobijn, and Valletta (2011), drawing on Valletta and

Kuang (2010), contrast changes in the unemployment durations of those

laid off from their previous jobs (whom I refer to as “job losers” below),

many of whom are eligible for UI benefits, and of other unemployed

individuals (many of whom quit their previous jobs), who are not, over

the course of the recession and after. They conclude that UI extensions

raised the unemployment rate by 0.8 percentage point in 2009 and early

2010. This comparison identifies the UI effect in the presence of arbitrary

changes in demand conditions, so long as the two groups are otherwise

similar. However, the collapse in the quit rate seen in figure 2 above sug-

gests that UI extensions may not be the only source of changes in the rela-

tive outcomes of job losers and job leavers. If the remaining job leavers

come largely from sectors where job openings are plentiful, while the job

losers come from sectors hit hard by the recession (such as construction),

the comparison between them will overstate any negative effect of UI

extensions.

A larger estimate comes from Robert Barro, in the op-ed cited in the

introduction, who assumes that the long-term unemployment share in 2009

would have been the same as in 1983 if not for the UI extensions. Barro

concludes that extensions raised the unemployment rate by 2.7 percentage

points. David Grubb’s (2011) literature review comes to a quite similar

conclusion. In contrast, Howell and Azizoglu (2011) conclude that any

160 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

effect is much smaller and primarily attributable to reduced labor force

exit induced by the UI job search requirement.

A final relevant paper is by Henry Farber and Valletta (2011). That

paper was written simultaneously with and independently of this one but

pursues a similar strategy of using recent data and competing-risks models

to identify the effect of UI extensions on reemployment and labor force

exit hazards. Unsurprisingly, Farber and Valletta obtain results very simi-

lar to those presented below. The analysis here differs from theirs in three

respects: it explores several alternative specifications that isolate different

components of the variation in UI benefits; it examines the sensitivity of

the results to unavoidable ad hoc assumptions made about expected benefit

availability; and it addresses an important discrepancy in the CPS data,

discussed below, that leads survival analyses to drastically understate the

long-term unemployment share and that has the potential to substantially

obscure effects of UI extensions on unemployment durations.

II. Data

I use the Current Population Survey rotating panel to measure the labor

market outcomes of a large sample of unemployed workers in the very

recent past. Three-quarters of each month’s CPS sample are targeted for

another interview the following month, and it is possible to match over

70 percent of monthly respondents (94 percent of the attempted reinter-

views) to employment status in the following month. (The most important

source of mismatches is individuals who move, who are not followed.)

This permits me to measure 1-month-later employment outcomes for

roughly 4,000 unemployed workers each month during and since the Great

Recession, and thereby to construct monthly reemployment and labor force

exit hazards that vary by state, date of unemployment, and unemployment

duration.

The CPS data have advantages and disadvantages relative to other data

that have been used to study UI extension effects. Advantages include

larger and more current samples, the ability to track outcomes for individu-

als who have exhausted their UI benefits or who are not eligible, and the

ability to distinguish reemployment from labor force exit.

These are offset by important limitations. First, the monthly CPS does

not contain measures of UI eligibility or receipt. Only job losers, those

who were laid off from their previous job rather than having quit or having

newly entered the labor force, are eligible for UI benefits. Past research has

found that fewer than half of the eligible unemployed actually receive UI

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 161

12. Observations in February, March, and April can be matched to data from the

Annual Demographic Survey, which includes questions about UI income in the previous

calendar year. In early 2010, 56 percent of job leavers whose unemployment spells appear

to have started before December 1, 2009, reported nonzero UI income, up from 39 percent

in early 2005.

benefits (Anderson and Meyer 1997). This fraction appears to have risen

somewhat since the onset of the Great Recession: I estimate that over half

of job losers unemployed more than 3 months in early 2010 received UI

benefits.

12

Although the UI participation rate is far less than 100 percent, I

simulate remaining benefit durations for all job losers, assuming that each

is eligible for full benefits. As I estimate relatively sparse specifications

without extensive individual controls, the estimates can be seen as the

“reduced form” average effect of available durations on the labor market

outcomes of all job losers, pooling recipients and nonrecipients. To imple-

ment the simulation, I match the CPS data to detailed information about

the availability of EUC and EB program benefits at a state-week level and

compute eligibility for benefits in each week between the beginning of the

unemployment spell and the initial CPS interview (including those paid

retroactively because of delayed reauthorizations). I assume that 1 week of

eligibility has been used for each week of covered unemployment (includ-

ing retroactive coverage due to delayed reauthorizations).

In modeling expectations for benefits subsequent to the CPS interview,

I assume in my main specifications that the individual anticipates no fur-

ther legislative action or triggering of benefits on or off after that date, as

in figure 4. Insofar as unemployed individuals are able to forecast future

legislation, I may understate the duration of expected benefits and over-

state the amount of variation across unemployment entry cohorts within

the same state. It is unclear in which direction this nonclassical measure-

ment error biases my results; I explore specifications aimed at reducing

this bias below.

A second limitation of the CPS data is that employment status and

unemployment durations are self-reported, and respondents may not fully

understand the official definitions. Officially, only someone who is out

of work, is available to start work, and has actively looked for work at

least once in the last 4 weeks should be classified as unemployed, with

a duration of unemployment reaching back to the last time he or she did

not meet these conditions. Someone who has not actively searched or is

unavailable to start a job is out of the labor force. But the line between

unemployment and nonparticipation can be blurry, particularly when there

are few suitable job openings or when job search is intermittent. The data

162 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

13. CPS procedures were altered in 1994, in part to reduce classification error. There

are no public-use reinterview samples from the post-1994 period. However, my analysis of

data supplied by Census Bureau staff suggests that the misclassification of unemployment

remains an important issue even after the redesign.

14. Fujita (2011) also recodes some U-N-U trajectories as U-U-U. I am grateful to Hank

Farber for helpful conversations about this issue.

15. I am unable to address a related potential problem: although the CPS data collection

is independent of that used to enforce job search requirements, these requirements may lead

some true nonparticipants to misreport themselves as active searchers. This may cause my

estimates of the effect of UI extensions on reported labor force participation to overstate the

effect on actual job search.

suggest that reported unemployment durations often stretch across periods

of non participation or short-term employment back to the perceived “true”

beginning of the unemployment spell. Reinterviews with CPS respondents

in the 1980s indicate important misclassification of labor force status, par-

ticularly for unemployed individuals, who are often misclassified as out of

the labor force. This leads to substantial overstatement of unemployment

exit probabilities (Poterba and Summers 1984, 1995, Abowd and Zellner

1985).

13

Relatedly, examination of the unemployment duration distribu-

tions indicates substantial heaping at monthly, semiannual, and annual

frequencies, suggesting that many respondents round their reported unem-

ployment durations.

To minimize the misclassification problem, my primary estimates

count someone who is observed to exit unemployment in one month but

return the following month—that is, someone whose 3-month trajectory

is unemployed-nonparticipating-unemployed (U-N-U) or unemployed-

employed-unemployed (U-E-U)—as a nonexit.

14

This means that I can

measure unemployment exits only for observations with at least two sub-

sequent interviews. I also estimate alternative specifications that count all

measured exits or that exclude many of the heaped observations, with

similar results.

15

I discuss these issues at greater length in section V.

Finally, as mentioned, the CPS does not attempt to track respondents

who change residences between interviews. Mobility and nonresponse lead

to the attrition of roughly 8 percent of the sample and 10 percent of the

unemployed respondents each month. If UI eligibility affects the propen-

sity to move (Frey 2009, Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl 2011), this could

bias my estimates in unknown ways. However, when I estimate my main

specifications using mobility as the dependent variable, I find no evidence

that it is (conditionally) correlated with my UI duration measures.

Table 2 presents summary statistics for my full CPS sample, which

pools data for interviews between May 2004 and January 2011, matched

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 163

Table 2. Summary Statistics

a

Percent except where stated otherwise

All unemployed

workers

b

Subsample with

two or more follow-up

interviews

c

Statistic

Job

losers

Job leavers,

entrants,

and

reentrants

Job

losers

Job leavers,

entrants,

and

reentrants

N

95,485

77,913

77,813 61,105

Share matched to 1

follow-up interview

91

91

100 100

Share matched to 2

follow-up interviews

85

83

100 100

Unemployment duration

(spells in progress)

Average (weeks)

22.7

21.8

23.1 22.2

Share 0–13 weeks

54

59

54 59

Share 14–26 weeks

17

15

17 15

Share 27–98 weeks

23

20

24 20

Share 99 weeks or more

5

6

5 6

Share exiting unemployment

by next month

Counting all exits

(1 or more follow-ups)

Total

39

52

38 51

To employment

23

20

23 20

Out of labor force

15

32

15 31

Not counting U-N-U or

U-E-U transitions

(2 or more follow-ups)

Total

30

42

29 41

To employment

20

18

20 18

Out of labor force

10

24

10 24

Anticipated duration of

unemployment benefits

(weeks)

Total

43.9

NA

44.2 NA

Remaining

24.1

NA

24.0 NA

Total (anticipating EUC

reauthorization)

56.7

NA

57.0 NA

State unemployment rate 7.7 6.9 7.7 6.9

Source: Author’s analysis.

a. All statistics use CPS weights. Shares may not sum to totals because of rounding. NA = not applicable.

b. All observations of unemployed workers from the May 2004–January 2011 CPS samples with

month-in-sample 1, 2, 5, or 6.

c. Excludes observations with missing or allocated labor force status in the base survey or in either of

the two following interviews, or with allocated unemployment duration in the base survey.

164 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

16. This is a lower exit rate than is apparent in the BLS gross flows data, which also

derive from matched CPS samples but do not incorporate my adjustment for U-N-U and

U-E-U trajectories.

to interviews in each of the next 2 months. (Rotation groups that would

not have been targeted for two follow-up interviews are excluded.) Fig-

ure 5 presents average monthly exit probabilities for unemployed workers

who report having been laid off from their previous job (as distinct from

new entrants to the labor force, reentrants, and voluntary job leavers) over

the sample period. The overall exit hazard fell from about 40 percent in

mid-2007 to about 25 percent throughout 2009 and 2010.

16

The figure also

reports exit hazards for those unemployed zero to 13 weeks and 26 weeks

or more. The hazard is higher for the short-term than for the long-term

unemployed. However, both series fell at rates similar to the overall aver-

age in 2007 and 2008, indicating that only a small portion of the overall

All

Unemployed 0–13 weeks

Unemployed 26 or more weeks

Percent

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the Current Population Survey.

a. Displaced workers are defined as unemployed individuals who report having lost their last job.

Hazards represent the probability of being employed or out of the labor force 1 month hence and not

unemployed the following month. Series are not seasonally adjusted and are smoothed using a 5-month

symmetric triangle moving average.

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Figure 5. Monthly Unemployment Exit Hazards for Displaced Workers,

by Duration Group, 2004–10

a

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 165

17. In principle, individuals can be followed for three periods in the CPS data.

(Although the CPS is a four-period rotating sample, I cannot measure exit between period 3

and period 4 because, as discussed above, I require a follow-up observation to identify tem-

porary exits.) Accounting for this would give rise to a somewhat more complex likelihood

function. I treat an individual observed for three periods as two distinct observations, one

on exit from period 1 to period 2 and another on exit from period 2 to period 3 (if she sur-

vives in unemployment in period 2), allowing for dependence of the error term across the

observations.

exit hazard decline can be attributed to composition effects arising from the

increased share of long-term unemployed.

III. Empirical Strategy

The matched CPS data allow me to measure whether an unemployed indi-

vidual exits unemployment over the next month, but they do not allow me

to follow those who do not exit to the end of their spells. I thus focus on

modeling the exit hazard directly. I assume the monthly hazard follows a

logistic function. To distinguish between the different forms of unemploy-

ment exit, I turn to a multinomial logit model that takes reemployment,

labor force exit, and continued unemployment as possible outcomes.

Let n

ist

be the number of weeks that unemployed person i in state s in

month t has been unemployed (censored at 99); let D

ist

be the total number

of weeks of benefits available to her, including the n

ist

weeks already used

as well as weeks she expects to be able to draw in the future; and let Z

st

be

a measure of economic conditions. Using a sample of job losers, I estimate

specifications of the form

() ln ;3

1

l

l

bg

ist

ist

istnistZs

DPnPZ

-

=+

()

+

t

ts

t

;.

dah

()

++

Here l

ist

is the probability that the individual exits unemployment by month

t + 1; a

s

and h

t

are fixed effects for states and months, respectively; and

P

n

and P

Z

are flexible polynomials. This logit specification can be seen as

a maximum likelihood estimator of a censored survival model with stock-

based sampling and a logistic exit hazard, with each individual observed for

only two periods.

17

However, as I discuss below, modeling survival func-

tions in the CPS data is challenging because of inconsistencies between

stock-based and flow-based measures of survival. In section V, I develop a

simulation approach to recovering survival curves from the estimated exit

hazards that are consistent with the observed duration profile. For now I

focus on modeling the hazards themselves.

166 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

After some experimentation, I settled on the following parameterization

of P

n

:

() ;

41

1

2

2

1

3

Pn nnnn

nist istist istist

gggg

()

=+++

-

≤≤

()

1

4

g .

This appears flexible enough to capture most of the duration pattern. I have

also estimated versions of equation 3 using fully nonparametric specifica-

tions of P

n

(n

ist

; g), with little effect on the results.

As discussed above, the main challenge in identifying the effect of D

ist

is that it covaries importantly with labor demand conditions. Absent true

random assignment of D

ist

, I explore several alternative strategies, aimed

at isolating different components of the variation in D

ist

that are plausibly

exogenous to unobserved determinants of unemployment exit.

My first strategy attempts to absorb labor demand conditions through

the P

Z

function. In my preferred specification, P

Z

is a cubic polynomial

in the state unemployment rate. I also explore richer specifications that

control as well for cubics in the insured unemployment rate (an alter-

native measure of unemployment based only on UI-eligible workers)

and in the number of new UI claims in the CPS week, expressed as a

share of the employed eligible population. The remaining variation in

D

ist

comes primarily from the haphazard rollout of EUC, which creates

variation over time in the relationship between Z

st

and the number of

weeks of available UI benefits. Additional variation derives from the

repeated expiration and renewal of the EUC program and from states’

decisions about whether to participate in the optional EB program. Note

that labor demand is likely to be negatively correlated with the avail-

ability of benefits, so specifications of P

Z

that do not adequately capture

demand conditions will likely lead me to overstate the negative effect of

UI benefits on job finding.

A second strategy uses job seekers who are not eligible for UI, either

because they are new entrants to the labor market or because they left their

former jobs voluntarily, to control nonparametrically for state labor market

conditions (Valletta and Kuang 2010, Farber and Valletta 2011). Using a

sample that pools all of the unemployed, I estimate

() ln5

1

l

l

ωb

ist

ist

istist istnis

DeDPn

-

=+ +

ttist istZ st st

eePZ,;

;,gd

a

()

+

()

+

where a

st

is a full set of state × month indicators and e

ist

is an indica-

tor for whether individual i is a job loser (and therefore presumptively

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 167

18. Three of the triggers are described in note 6. The fourth is activated when the

3-month moving-average total unemployment rate exceeds 8 percent and is above 110 per-

cent of the lesser of its 1-year and 2-year lagged values. States adopting optional trigger 3

are required to also adopt trigger 4, which when activated provides an additional 7 weeks of

benefits on top of the normal 13.

UI-eligible). P

n

(n

ist

, e

ist

; g) = P

n

(n

ist

; g

0

) + e

ist

P

n

(n

ist

; g

1

) + e

ist

g

2

represents

the full interaction of the unemployment duration controls in equation 4

with the eligibility indicator, and e

ist

P

Z

(Z

st

; d) indicates that the relative

labor market outcomes of job losers and other unemployed are allowed

to vary parametrically with observed labor market conditions. The D

ist

measure of the number of weeks available is calculated for everyone,

eligible and ineligible alike, and is entered both as a main effect, to

absorb any correlation between cohort employability and benefits, and

interacted with the eligibility indicator e

ist

. The effect attributable to UI

duration, b, is identified from covariance between UI extensions and

changes in the relative unemployment exit rates of job losers and other

unemployed workers who entered unemployment at the same time, over

and above that which can be explained by the Z

st

controls.

This specification has the advantage that it does not rely on parametric

controls to measure the absolute effect of economic conditions on job find-

ing rates. However, recall that figure 2 indicated that the quit rate has been

low throughout the recession and since. If the ineligible unemployed during

the period when benefits were extended are disproportionately composed

of people who have relatively good employment prospects, the evolving

prospects of the population of ineligibles may not be a good guide to those

of eligibles, leading the specification in equation 5 to overstate the effect

of UI extensions. I attempt to minimize this by adding controls for sev-

eral individual covariates—age, education, sex, marital status, and former

occupation and industry—to equation 5.

My third strategy returns to the eligibles-only sample but narrows in

on the variation in UI durations coming from state decisions about which

EB triggers to adopt, using a control function to absorb all other varia-

tion in D

ist

. I augment equation 3 with a direct control for the number of

EUC weeks available. This leaves variation only in EB program benefits

(and, incidentally, eliminates my reliance on assumptions about job seek-

ers’ expectations of future EUC reauthorization, as the EB program is not

set to expire). I also add controls for the availability of EB program benefits

in the state × month cell under maximal and minimal state participation in

the EB program (as graphed in figure 3), along with indicators for whether

the state has exceeded each of the four EB thresholds.

18

With these controls,

168 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

the only variation in D

ist

should come from differences among states in

similar economic circumstances in take-up of the optional EB triggers.

My final strategy turns to an entirely different source of variation, focus-

ing on the interaction between the number of available weeks in the state

and the number of weeks that the individual has used to date. Equations 3

and 5 model the effect of UI extensions as a constant shift in the log odds

of unemployment exit, reemployment, or labor force exit; in some speci-

fications I allow separate effects on those unemployed more or less than

26 weeks. But this is a crude way of capturing the effects, which the model

in section I.C suggests are likely to be stronger for those facing imminent

exhaustion than for those for whom an extension only adds to the end of

what is already a long stream of anticipated future benefits.

To focus better on this, I turn to a specification that parameterizes the

UI effect in terms of the time to exhaustion:

() ln ;6

1

1

l

l

bυ

υ

ist

ist

istist

fd n

-

=

()

+=

()

=00

99

∑

+

ga

υ st

.

Here d

ist

= max{0, D

ist

- n

ist

} represents the number of weeks of benefits

remaining, with f(z; b) a flexible function; I impose only the normalization

that f(0; b) = 0, implying that UI durations have no effect on job searchers

who have already exhausted all UI benefits. The second term on the right-

hand side of equation 6 is a full set of indicators for unemployment dura-

tion, and the third is a full set of state × month indicators. There are two

sources of variation that allow separate identification of the effects of d and

n, within state × month cells, without parametric restrictions. The first is

the nonlinearity of the mapping from D

ist

and n

ist

to d

ist

: across–state × month

variation in benefit availability has one-for-one effects on d

ist

for those who

have not yet exhausted benefits but not for those who have. Second, the

EUC expiration rules mean that the addition of new EUC tiers extends d

for those who will transition onto the new tiers before the EUC program

expires but not for those with lower n

ist

, who will expect the program to

have expired before they reach the new tiers.

IV. Estimates

The top panel of table 3 presents logit estimates of equation 3, with stan-

dard errors clustered at the state level. The table shows the unemployment

duration coefficient and its standard error. Below these, it also shows the

estimated effect of the UI extensions on the average exit hazard in the

Table 3. Logit Regressions Estimating Effects of UI Extensions on Unemployment Exit Hazards

a

Independent variables and calculated effects of UI extensions

Sample: job losers (N = 77,813)

b

Sample: all

unemployed

workers

(N = 138,883)

c

3-1 3-2 3-3 3-4 3-5 3-6 3-7

Assuming constant effect of UI across all durations

Weeks of UI benefits/100 -0.33

(0.10)

-0.27

(0.10)

-0.31

(0.10)

-0.34

(0.10)

-0.37

(0.10)

-0.15

(0.10)

-0.19

(0.10)

Effect of UI extensions on average exit hazard, 2010Q4 (percentage points)

d

-2.1 -1.7 -1.9 -2.1 -2.3 -0.9 -1.2

Controls

State unemployment rate No Linear Cubic Cubic Cubic No No

State insured unemployment rate

e

No No No Cubic Cubic No No

State new UI claims rate

f

No No No Cubic Cubic No No

State employment growth rate No No No Cubic Cubic No No

Individual covariates

g

No No No No Yes No Yes

(continued)

Table 3. Logit Regressions Estimating Effects of UI Extensions on Unemployment Exit Hazards

a

(Continued)

Independent variables and calculated effects of UI extensions

Sample: job losers (N = 77,813)

b

Sample: all

unemployed

workers

(N = 138,883)

c

3-1 3-2 3-3 3-4 3-5 3-6 3-7

Allowing effect to vary by individual unemployment duration

h

Weeks of UI benefits/100 × unemployed less than 26 weeks 0.08

(0.15)

0.20

(0.15)

0.13

(0.15)

0.10

(0.14)

0.10

(0.14)

-0.11

(0.19)

-0.13

(0.19)

Weeks of UI benefits/100 × unemployed 26 or more weeks -0.37

(0.09)

-0.30

(0.10)

-0.34

(0.09)

-0.36

(0.09)

-0.40

(0.09)

-0.19

(0.10)

-0.23

(0.11)

Effect of UI extensions on average exit hazard, 2010Q4 (percentage points)

d

-1.5 -1.0 -1.3 -1.4 -1.6 -1.0 -1.3

Source: Author’s analysis.

a. Standard errors clustered at the state level are in parentheses.

b. Average monthly exit hazard in the full sample is 29.4 percent; that in the 2010Q4 subsample is 22.4 percent. All specifications using this sample use the CPS sample

weights and include state fixed effects, month fixed effects, and unemployment duration controls (weeks of unemployment as reported in the beginning-of-month survey,

its square, its inverse, and an indicator variable for being unemployed 1 week or less).

c. Specifications include unemployment duration controls (see note b), state × month fixed effects, an indicator variable for whether the individual is a job loser, interactions

of the job loser indicator with the unemployment duration controls and with a cubic in the state unemployment rate, and the number of weeks of benefits the individual would

receive if eligible. Estimation is by conditional logit and uses the average CPS weight in the state × month cell.

d. Difference between the average fitted exit probability and the fitted probability implied by the model if benefit durations had been held fixed at 26 weeks.

e. UI claimants as a share of all insured workers.

f. New UI claims as a share of all insured workers.

g. Sex and marital status indicators, a female-married interaction, and age, education, and preunemployment industry indicators (6, 4, and 15 categories, respectively).

h. Specifications are the same as in the top panel but also include an indicator for whether the individual has been unemployed 26 weeks or more.

JESSE ROTHSTEIN 171

19. Strictly speaking, I use observations from the September through November surveys.

December observations are excluded because the EUC program had expired and not yet been

renewed at the time of the December survey; see section I.B.

20. For computational reasons, I estimate the specification by conditional logit, then

back out consistent but inefficient estimates of the a

st

fixed effects for use in predicted exit

probabilities.

fourth quarter of 2010, computed as the difference between the average fit-

ted exit probability and the average fitted probability implied by the model

with benefit durations set to 26 weeks for the entire sample.

19

The regres-

sion reported in column 3-1 is estimated using only job losers, who are

presumed to be eligible for UI benefits, and includes state and month fixed

effects and the n

ist

controls indicated by equation 4, but no controls for eco-

nomic conditions in the state or for individual characteristics. It indicates

a significant negative effect of UI benefit durations on the probability of

unemployment exit, with a net effect of the UI extensions on the 2010Q4

exit rate of -2.1 percentage points (on a base of 22.4 percent). Columns

3-2 through 3-5 add additional controls: column 3-2 adds a control for the

state unemployment rate, column 3-3 uses a cubic in that rate, column 3-4

adds cubics in three other measures of slackness (the number of UI claim-

ants and the number of new UI claims, each expressed as a share of insured

employment, and the state employment growth rate), and finally column

3-5 adds a vector of individual-level covariates, including indicators for

education, age, sex, marital status, and industry of previous employment.

The estimated effects of UI durations move around a bit as the covariate

vector is expanded, but within a fairly narrow range: the implied effects on

the exit hazard in 2010Q4 range from -1.7 to -2.3 percentage points.

Columns 3-6 and 3-7 turn to my second strategy, adding to the sample

over 60,000 unemployed individuals who left their jobs voluntarily or are

new entrants to the labor force and are therefore not eligible for UI ben-

efits. As indicated by equation 5, this allows me to add state × month fixed

effects.

20

I also include an indicator for (simulated) UI eligibility and its

interaction with the duration and unemployment rate controls, as well as

a “simulated UI duration” control that is common to both the job losers

and the job leavers and designed to capture any unobserved cohort effects

that are common to both groups but correlated with my UI measure. Col-

umn 3-7 also adds the full vector of individual covariates, as a guard

against the possibility of important differences in employability between

the job losers and the UI-ineligible comparison group. With or without

these covariates, the estimates indicate notably smaller effects than in the

first five columns.

172 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2011

There is no particular reason to think that benefit extensions have the

same effects on those near benefit exhaustion as on those just beginning

their unemployment spells. As a first step toward loosening this assump-

tion, in the bottom panel of the table I allow D

ist

to have different effects

on those unemployed less than 26 weeks and those unemployed 26 weeks

or longer. The negative effect of D on unemployment exit is found to

be entirely concentrated among the latter, with estimated effects on the

shorter-term unemployed that are close to zero, never statistically signifi-

cant, and in many cases positive. The coefficients for the long-term unem-

ployed are somewhat larger than in the top panel, though the differences

are small. The implied effects of UI extensions on exit hazards are smaller

than those in the top panel in the first five columns, but larger in the last

two, narrowing the gap between the two sets of specifications.

Table 4 presents several specifications aimed at gauging the sensi-

tivity of the estimates to the measurement of expected future benefits.

Column 4-1 repeats the results for the baseline specification from col-

umn 3-3 in the bottom panel of table 3. Column 4-2 replaces the anticipated

Table 4. Specifications Examining the Sensitivity of Results to the Recipient

Expectations Model

a

Independent variables and calculated