Financial Stability Report

June 2017

|

Issue No. 41

Financial Stability Report

Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9W(10) of the Bank of England

Act 1998 as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012.

June 2017

BANK OF ENGLAND

© Bank of England 2017

ISSN 1751-7044

BANK OF ENGLAND

Financial Stability Report

June 2017 | Issue No. 41

The primary responsibility of the Financial Policy Committee (FPC), a committee of the Bank of England, is

to contribute to the Bank of England’s objective for maintaining financial stability. It does this primarily by

identifying, monitoring and taking action to remove or reduce systemic risks, with a view to protecting and

enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system. Subject to that, it supports the economic policy of

Her Majesty’s Government, including its objectives for growth and employment.

This Financial Stability Report sets out the FPC’s view of the outlook for UK financial stability, including its

assessment of the resilience of the UK financial system and the current main risks to financial stability, and

the action it is taking to remove or reduce those risks. It also reports on the activities of the Committee

over the reporting period and on the extent to which the Committee’s previous policy actions have

succeeded in meeting the Committee’s objectives. The Report meets the requirement set out in legislation

for the Committee to prepare and publish a Financial Stability Report twice per calendar year.

In addition, the Committee has a number of duties, under the Bank of England Act 1998. In exercising

certain powers under this Act, the Committee is required to set out an explanation of its reasons for

deciding to use its powers in the way they are being exercised and why it considers that to be compatible

with its duties.

The Financial Policy Committee:

Mark Carney, Governor

Jon Cunliffe, Deputy Governor responsible for financial stability

Ben Broadbent, Deputy Governor responsible for monetary policy

Sam Woods, Deputy Governor responsible for prudential regulation

Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the Financial Conduct Authority

Alex Brazier, Executive Director for Financial Stability Strategy and Risk

Anil Kashyap

Donald Kohn

Richard Sharp

Martin Taylor

Charles Roxburgh attends as the Treasury member in a non-voting capacity.

This document was delivered to the printers on 26 June 2017 and, unless otherwise stated, uses data available

as at 16 June 2017. This page was revised on 11 April 2018.

The Financial Stability Report is available in PDF at www.bankofengland.co.uk.

Foreword

Executive summary i

Box 1 The FPC’s 2017 Q2 UK countercyclical capital buffer rate decision vi

Box 2 Possible financial stability implications of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from

the European Union vii

Part A: Main risks to financial stability

The FPC’s approach to addressing risks from the UK mortgage market 1

Box 3 PRA Supervisory Statement on underwriting standards for buy-to-let mortgages 11

Box 4 Powers of Direction over LTV limits 12

Box 5 The affordability test Recommendation 13

UK consumer credit 14

Box 6 Overview of the UK consumer credit market 18

Global environment 20

Asset valuations 23

Part B: Resilience of the UK financial system

Banking sector resilience 27

Box 7 Building cyber resilience in the UK financial system 32

Market-based finance 34

Box 8 The UK High-Value Payment System 39

The FPC’s medium-term priorities 41

Annex 1: Previous macroprudential policy decisions 42

Annex 2: Core indicators 45

Index of charts and tables 49

Glossary and other information 51

Contents

E

xecutive summary

i

Executive summary

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) aims to ensure the UK financial system is resilient to the wide range of risks it

faces.

The FPC assesses the overall risks from the domestic environment to be at a standard level: most financial stability

indicators are neither particularly elevated nor subdued.

As is often the case in a standard environment, there are pockets of risk that warrant vigilance. Consumer credit has

increased rapidly. Lending conditions in the mortgage market are becoming easier. Lenders may be placing undue

weight on the recent performance of loans in benign conditions.

Exit negotiations between the United Kingdom and the European Union have begun. There are a range of possible

outcomes for, and paths to, the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU.

Some possible global risks have not crystallised, though financial vulnerabilities in China remain pronounced.

Measures of market volatility and the valuation of some assets — such as corporate bonds and UK commercial real

estate — do not appear to reflect fully the downside risks that are implied by very low long-term interest rates.

To ensure that the financial system has the resilience it needs, the FPC is:

• Increasing the UK countercyclical capital buffer rate to 0.5%, from 0%. Absent a material change in the

outlook, and consistent with its stated policy for a standard risk environment and of moving gradually, the FPC

expects to increase the rate to 1% at its November meeting.

• Bringing forward the assessment of stressed losses on consumer credit lending in the Bank’s 2017 annual stress

test. This will inform the FPC’s assessment at its next meeting of any additional resilience required in aggregate

against this lending. The FPC further supports the intentions of the Prudential Regulation Authority and Financial

Conduct Authority to publish, in July, their expectations of lenders in the consumer credit market.

• Clarifying its existing insurance measures in the mortgage market, designed to prevent excessive growth in the

number of highly indebted households. This will promote consistency across lenders in their application of tests to

assess whether new mortgage borrowers can afford repayments.

• Consistent with its previous commitment, restoring the level of resilience delivered by its leverage ratio

standard to the level it delivered in July 2016 before the FPC excluded central bank reserves from the leverage ratio

exposure measure. The FPC intends to set the minimum leverage requirement at 3.25% of non-reserve exposures,

subject to consultation.

• Overseeing contingency planning to mitigate risks to financial stability as the United Kingdom withdraws from

the European Union.

• Building on the programme of cyber resilience testing it instigated in 2013, by setting out the essential elements

of the regulatory framework for maintaining cyber resilience. It will now monitor that each element is being

fulfilled by the relevant UK authorities.

i

i Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) assesses the overall

risks from the domestic environment to be at a standard

l

evel: most financial stability indicators are neither

particularly elevated nor subdued.

As is often the case in a standard environment, there are

pockets of risk that warrant vigilance. Consumer credit has

i

ncreased rapidly. Lending conditions in the mortgage

market are becoming easier. Lenders may be placing undue

weight on the recent performance of loans in benign

conditions.

The FPC is increasing the UK countercyclical capital buffer

(CCyB) rate to 0.5%, from 0% (see Box 1). Absent a

material change in the outlook, and consistent with its

stated policy for a standard risk environment and of moving

gradually, the FPC expects to increase the rate to 1% at its

November meeting.

• The action will supplement banks’ already substantial

ability to absorb losses (Chart A).

• At its November meeting, the FPC will have the full set of

results from the 2017 stress test of major UK banks.

• In line with its published policy, the FPC stands ready to cut

the UK CCyB rate, as it did in July 2016, if a risk materialises

t

hat could lead to a material tightening of lending

conditions. Banks’ capital buffers exist to be used as

necessary to allow banks to support the real economy in a

downturn.

T

he FPC supports the intentions of the Prudential

Regulation Authority (PRA) and Financial Conduct

Authority (FCA) to publish, in July, their expectations of

lenders in the consumer credit market. Firms remain the

first line of defence. Effective governance at firms should

ensure that risks are priced and managed appropriately and

benign conditions do not lead to complacency by lenders.

The Bank’s annual stress test assesses banks’ resilience to

risks in consumer credit. Given the rapid growth in

consumer credit over the past twelve months, the FPC is

bringing forward the assessment of stressed losses on

consumer credit lending in the Bank’s 2017 annual stress

test. This will inform the FPC’s assessment at its next

meeting of any additional resilience required in aggregate

against this lending.

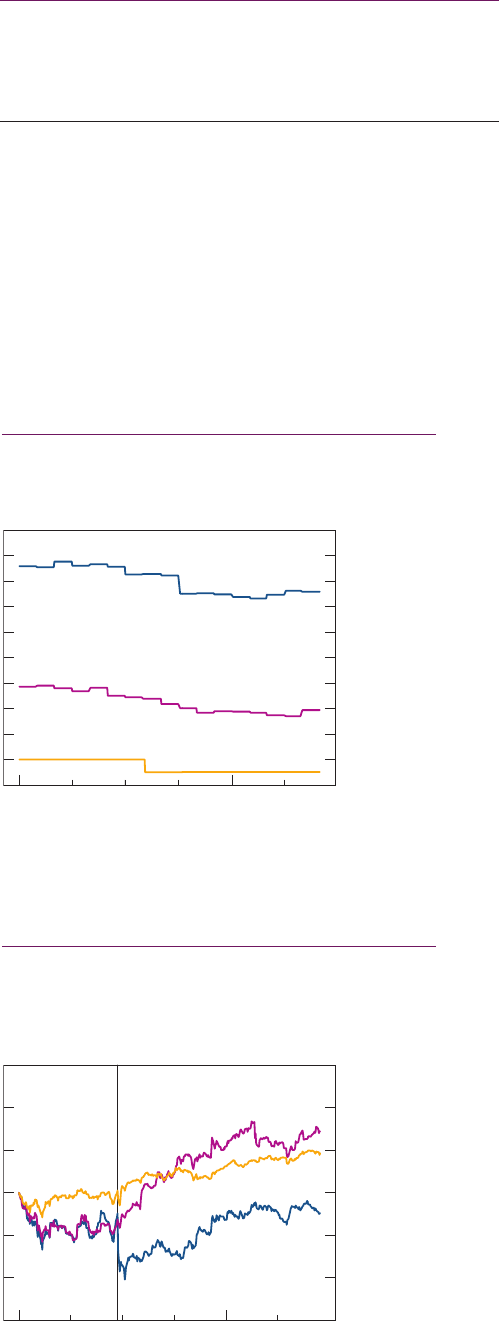

• Consumer credit grew by 10.3% in the twelve months to

April 2017 (Chart B) — markedly faster than nominal

household income growth. Credit card debt, personal loans

and motor finance all grew rapidly.

5

0

5

10

15

20

25

2013 14 15 16 17

Percentage points

Total consumer credit

(b)

Credit card

(b)

Dealership car finance

(a)

Other (non-credit card and non-dealership car finance)

(b)(d)

Nominal household income growth

(c)

+

–

Chart B Consumer credit has been growing much faster

than household incomes

Annual growth rates of consumer credit products and household

income

Sources: Bank of England, ONS and Bank calculations.

(a) Identified dealership car finance lending by UK monetary financial institutions (MFIs) and

other lenders.

(b) Sterling net lending by UK MFIs and other lenders to UK individuals (excluding student

loans). Non seasonally adjusted.

(c) Percentage change on a year earlier of quarterly nominal disposable household income.

Seasonally adjusted.

(d) Other is estimated as total consumer credit lending minus dealership car finance and credit

card lending.

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

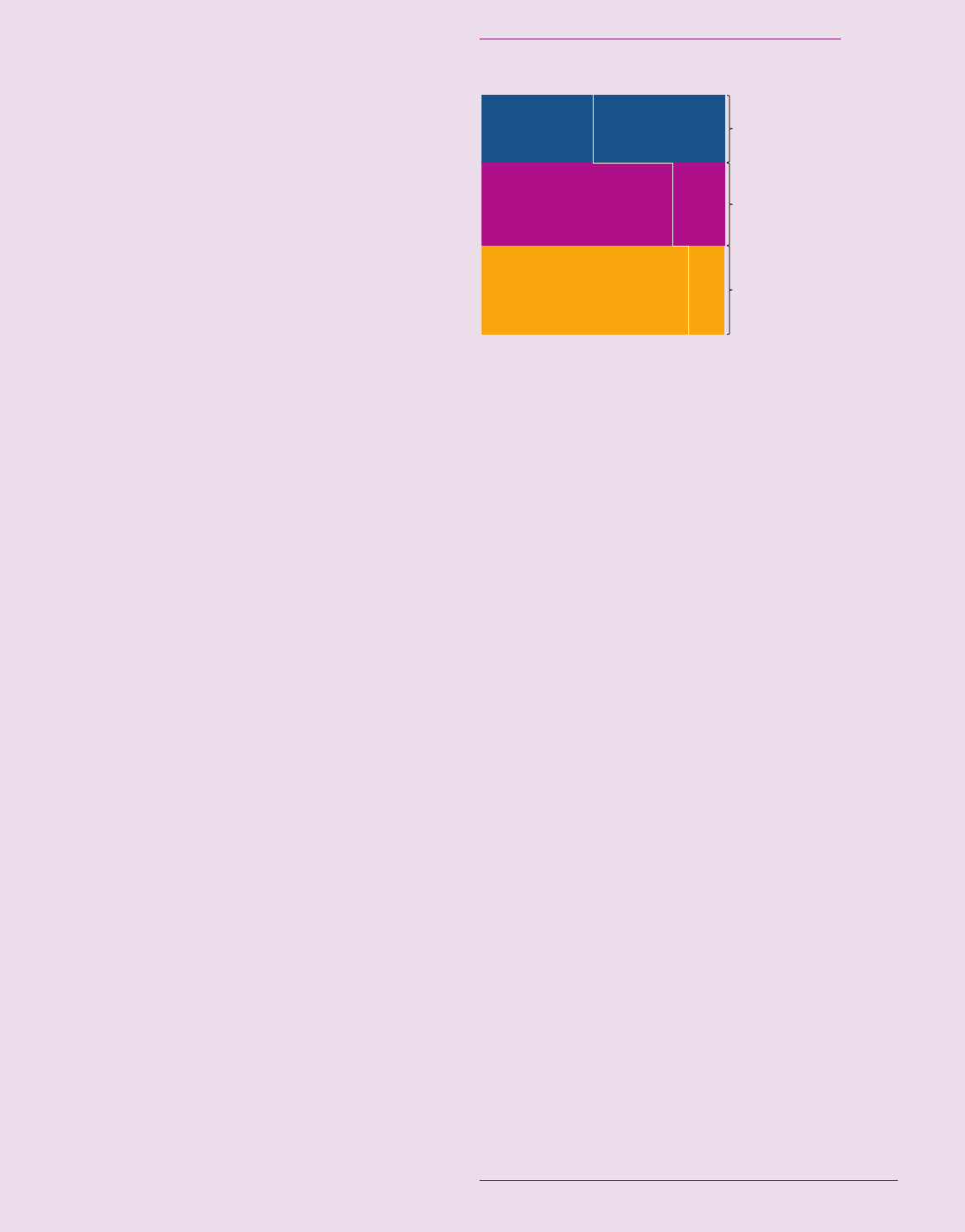

2001 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

Per cent

Per cent

B

asel III common equity Tier 1

(CET1) weighted average

(c)(d)

(right-hand scale)

B

asel II core Tier 1 weighted

average

(a)(b)(c)

(left-hand scale)

C

ET1 ratio adjusted for 2016

s

tress-test losses

(e)

(right-hand scale)

B

asel III definition of capital

Chart A Major UK banks have continued to strengthen

their capital positions

Major UK banks’ capital ratios

Sources: PRA regulatory returns, published accounts and Bank calculations.

(a) Major UK banks’ core Tier 1 capital as a percentage of their risk-weighted assets. Major UK

banks are Banco Santander, Bank of Ireland, Barclays, Co-operative Banking Group, HSBC,

Lloyds Banking Group, National Australia Bank, Nationwide, RBS and Virgin Money. Data

exclude Northern Rock/Virgin Money from 2008.

(b) Between 2008 and 2011, the chart shows core Tier 1 ratios as published by banks, excluding

hybrid capital instruments and making deductions from capital based on FSA definitions.

Prior to 2008 that measure was not typically disclosed; the chart shows Bank calculations

approximating it as previously published in the Report.

(c) Weighted by risk-weighted assets.

(d) From 2012, the ‘Basel III common equity Tier 1 capital ratio’ is calculated as common equity

Tier 1 capital over risk-weighted assets, according to the CRD IV definition as implemented in

the United Kingdom. The Basel III peer group includes Barclays, Co-operative Banking Group,

HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group, Nationwide, RBS and Santander UK.

(e) CET1 ratio less the aggregate percentage point fall projected under the Bank of England’s

2016 annual cyclical stress scenario for the six largest UK banks.

E

xecutive summary

iii

• Loss rates on consumer credit lending are low at present.

Partly as a result, banks’ net interest margins on new

l

ending have fallen and major lenders are using lower risk

weights to calculate the capital they need to hold. The

current environment is also likely to have improved the

credit scores of borrowers.

•

Other things equal, these developments mean lenders have

less capacity to absorb losses, either with income or capital

buffers. In this context, a review by the PRA has found

evidence of weaknesses in some aspects of underwriting

and a reduction in resilience.

• The short maturity of consumer credit means that the

credit quality of the stock of lending can deteriorate

quickly. Lenders expect to continue to grow their portfolios

this year, at the same time as real household income

growth is expected to remain particularly weak.

The FPC has clarified its existing insurance measures in the

mortgage market, designed to prevent excessive growth in

the number of highly indebted households. Lenders should

test affordability at their mortgage reversion rate —

typically their standard variable rate — plus 3 percentage

points. This will promote consistency across lenders in their

application of tests to assess whether new mortgage

borrowers can afford repayments.

• Historically, the build-up of mortgage debt has been a

significant risk to financial and economic stability. Because

highly indebted borrowers need to cut spending sharply in a

downturn, recessions become deeper. And looser

underwriting standards expose banks to bigger losses.

• The FPC put policies in place to guard against these risks

in 2014. These Recommendations were: a limit on lending

at loan to income multiples at 4.5 or above; and guidance

to lenders to assess whether new borrowers would be

able to afford their repayments if interest rates were to

rise.

• Following a review (see The FPC’s approach to addressing

risks from the UK mortgage market chapter), the FPC

expects its measures to remain in place for the foreseeable

future.

• Mortgage lending at high loan to income ratios is increasing

and the spreads and fees on mortgage lending have fallen.

If lenders were to weaken underwriting standards to

maintain mortgage growth, the FPC’s measures would

limit growth in the number of highly indebted households.

This would have material benefits for economic and

financial stability by mitigating the further cutbacks in

spending that highly indebted households make in

downturns.

Consistent with its previous commitment, the FPC is

restoring the level of resilience delivered by its leverage

r

atio standard to the level it delivered in July 2016, before

the FPC excluded central bank reserves from the leverage

ratio exposure measure. The FPC therefore intends to set

the minimum leverage requirement at 3.25% of

non-reserve exposures, subject to consultation.

• In July 2016, the FPC excluded central bank reserves from

the measure of banks’ exposures used to assess their

leverage. This change reflected the special nature of central

bank reserves and was designed to avoid a situation in

which the Committee’s leverage standards impeded the

transmission of monetary policy.

• The FPC committed last year that it would make an

offsetting adjustment to ensure that the amount of capital

needed to meet the UK leverage ratio standard would not

decline. The FPC did not intend for there to be a

permanent loosening of the standard.

• By raising the minimum leverage standard from 3% to

3.25%, the FPC intends to ensure that the original standard

of resilience is restored, while also preserving the benefits

of excluding central bank reserves from the exposure

measure.

Exit negotiations between the United Kingdom and the

European Union have begun. There are a range of possible

outcomes for, and paths to, the United Kingdom’s

withdrawal from the EU. The FPC will oversee contingency

planning to mitigate risks to financial stability as the

withdrawal process evolves (see Box 2).

Irrespective of the particular form of the United Kingdom’s

future relationship with the European Union, and consistent

with its statutory responsibility, the FPC will remain

committed to the implementation of robust prudential

standards in the UK financial system. This will require a

level of resilience to be maintained that is at least as great

as that currently planned, which itself exceeds that required

by international baseline standards.

• The United Kingdom’s position as the leading

internationally active financial centre, with a financial

centre that is, by asset size, around ten times GDP, means

that the FPC’s statutory responsibility of protecting and

enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system is

particularly important for both the domestic and global

economies.

• Absent consistent implementation of standards

internationally and appropriate supervisory co-operation,

the FPC would need to assess how best to protect the

resilience of the UK financial system.

i

v Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

Some possible global risks have not crystallised, though

financial vulnerabilities in China remain pronounced.

Measures of market volatility and the valuation of some

assets — such as corporate bonds and UK commercial real

e

state — do not appear to reflect fully the downside risks

that are implied by very low long-term interest rates.

Banks’ ability to withstand these risks is being tested in the

2017 stress test scenario.

• Euro-area sovereign bond spreads have fallen as some

political uncertainties have been resolved. Further progress

has been made in strengthening European bank capital

positions, and a domestically significant bank in Spain was

resolved in an orderly fashion.

• In China, capital outflows have stabilised, but economic

growth continues to be accompanied by rapid credit

expansion (Chart C).

• Measures of uncertainty implied by options prices are low

(see Asset valuations chapter). Often in periods of low

volatility, risks are building and later become apparent.

• In the United Kingdom, ten-year real government bond

yields are at around -2% (Chart D). Long-term real rates

are low across the G7. These levels are consistent with

pessimistic growth expectations and high perceived tail

risks.

• Some asset valuations, particularly for some corporate

bonds and UK commercial real estate assets, appear to

factor in a low level of long-term market interest rates but

do not appear to be consistent with the pessimistic and

u

ncertain outlook embodied in those rates (Chart E).

0

10

20

30

40

50

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2006 08 10 12 14 16

Non-financial sector

(a)

(right-hand scale)

A

djusted total social financing

(b)

(left-hand scale)

H

eadline total social financing

(c)

(left-hand scale)

P

ercentage changes on a year earlier Per cent of GDP

Chart C Credit continues to grow rapidly in China

China non-financial sector debt and growth of total social

financing

Sources: BIS total credit statistics, CEIC and Bank calculations.

(a) Non-financial sector debt data are to 2016 Q4. Includes lending by all sectors at market

value as a percentage of GDP, adjusted for breaks.

(b) Total social financing adjusted for net issuance of local government bonds.

(c) The People’s Bank of China stock of total social financing used from December 2014

onwards. Prior to this the stock of total social financing is estimated using monthly ‘newly

increased’ total social financing flows.

3

2

1

0

1

2

3

4

2006 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

United Kingdom

United States

E

uro area

Per cent

+

–

Chart D Advanced-economy risk-free real interest rates

remain close to historically low levels

International ten-year real government bond yields

(a)

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank calculations.

(a) Zero-coupon bond yields derived using inflation swap rates. UK real rates are defined

relative to RPI inflation, whereas US and euro-area real rates are defined relative to CPI and

HICP inflation respectively.

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

03 05 07 09 11 13 15 17

Indices: 2007 Q2 = 100

2001

London West End

office prices

Aggregate

CRE prices

Ranges of sustainable valuations

(a)

Upper part of ranges: low rental yields persist.

Lower part of ranges: rental yields rise,

consistent with a fall in rental growth

expectations or a rise in risk premia.

Chart E UK commercial real estate prices look stretched

based on ranges of sustainable valuations

Commercial real estate prices in the United Kingdom and ranges

of sustainable valuations

Sources: Bloomberg, Investment Property Forum, MSCI Inc. and Bank calculations.

(a) Sustainable valuations are estimated using an investment valuation approach and are based

on an assumption that property is held for five years. The sustainable value of a property is

the sum of discounted rental and sale proceeds. The rental proceeds are discounted using a

5-year gilt yield plus a risk premium, and the sale proceeds are discounted using a 20-year,

5-year forward gilt yield plus a risk premium. Expected rental value at the time of sale is

based on Investment Property Forum Consensus forecasts. The range of sustainable

valuations represents varying assumptions about the rental yield at the time of sale: either

rental yields remain at their current levels (at the upper end), or rental yields revert to their

15-year historical average (at the lower end). For more details, see Crosby, N and Hughes, C

(2011), ‘The basis of valuations for secured commercial property lending in the UK’, Journal of

European Real Estate Research, Vol. 4, No. 3, pages 225–42.

E

xecutive summary

v

• These asset prices are therefore vulnerable to a repricing,

whether through an increase in long-term interest rates or

an adjustment of growth expectations, or both. The impact

of this could be amplified given reduced liquidity in some

m

arkets.

Progress has been made in building resilience to cyber

attack, but the risk continues to build and evolve.

Regulators are nearing completion of a first round of cyber

resilience testing for all firms at the core of the UK financial

system, in line with the Recommendation from the FPC in

2015.

• The FPC’s concern is to mitigate systemic risk — the risk of

material disruption to the economy.

• With 31 out of 34 firms at the core of the UK financial

system, including banks representing more than 80% of the

outstanding stock of PRA-regulated banks’ lending to the

UK real economy, so far having completed penetration

testing and having action plans in place, the FPC is satisfied

that its 2015 Recommendation has been met.

• Consistent with that, the FPC is also setting out the

essential elements of the regulatory framework for

maintaining cyber resilience and will now monitor that each

element is being fulfilled by the relevant UK authorities.

• Alongside the Bank, PRA and FCA, the FPC will now

consider its tolerance for the disruption to important

economic functions of the financial system in the event of

cyber attack.

The FPC has updated its medium-term priorities (see

The FPC’s medium-term priorities chapter).

• The FPC’s primary responsibility is to identify, monitor and

t

ake action to remove or reduce systemic risks, with a view

to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK

financial system. It aims to ensure the financial system

does not cause problems for the rest of the economy and, if

and when problems arise in the economy, the financial

system can absorb rather than amplify them.

• To help to meet its objectives, alongside its ongoing

assessment of the risk environment, the FPC is prioritising

three initiatives over the next two to three years:

• Finalising, and refining if necessary, post-crisis bank

capital and liquidity reforms.

• Completing post-crisis reforms to market-based finance

in the United Kingdom, and improving the assessment of

systemic risks across the financial system.

• Preparing for the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the

European Union.

Part A of this Report sets out in detail the Committee’s

analysis of the major risks and action it is taking in the light of

those risks. Part B summarises the Committee’s analysis of

the resilience of the financial system.

v

i Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

Box 1

The FPC’s 2017 Q2 UK countercyclical capital

buffer rate decision

The FPC is increasing the UK countercyclical capital buffer

(CCyB) rate from 0% to 0.5%, with binding effect from

27 June 2018. Absent a material change in the outlook, and

consistent with its stated policy for a standard risk

e

nvironment and of moving gradually, the FPC expects to

increase the rate to 1% at its November meeting, with

binding effect a year after that. At that point, it will have the

full set of results from the 2017 stress test of major UK banks.

The increase to 0.5% will raise regulatory buffers of common

equity Tier 1 capital by £5.7 billion. This will provide a buffer

of capital that can be released quickly in the event of an

adverse shock occurring that threatens to tighten lending

conditions. The increase in the CCyB rate will also lead to a

proportional increase in major UK banks’ leverage

requirements via the countercyclical leverage buffer (CCLB).

The Committee’s decision to increase the UK CCyB rate to

0.5% — with an expectation of a further increase to 1% in

November — reflects its assessment of the current risk

environment and its intention to vary the buffer in gradual

steps.

In its published strategy for setting the CCyB, the FPC

signalled that it expects to set a UK CCyB rate in the region of

1% in a standard risk environment. The FPC assesses the

overall risks from the domestic environment to be at a

standard level: most financial stability indicators are neither

particularly elevated nor subdued. Domestic credit has grown

broadly in line with nominal GDP over the past two years

(Chart A). Within the overall risk environment, some

indicators are more benign. For example, despite high levels of

indebtedness, private sector debt-servicing costs are low,

supported by the low level of interest rates. In contrast, risk

levels in some sectors are more elevated, notably so in the

consumer credit market (see UK consumer credit chapter).

Global risks — which could influence the risks on UK exposures

indirectly via their potential effects on UK economic growth —

are also judged to be material, as are risks from some asset

valuations.

The FPC’s measured approach is likely to decrease the risk that

banks adjust by tightening credit conditions, thereby

minimising the cost to the economy of making the banking

system more resilient.

In line with its published policy, the FPC stands ready to cut

the UK CCyB rate, as it did in July 2016, if a risk materialises

that could lead to a material tightening of lending conditions.

The cut in the CCyB rate in July 2016 was a response to

greater uncertainty around the UK economic outlook and an

increased possibility that material domestic risks could

crystallise in the near term. The FPC’s action served to ensure

banks did not hoard capital and restrict lending in those

conditions. Banks’ capital buffers exist to be used as necessary

to allow banks to support the real economy in a downturn.

Under EU law, the UK CCyB rate applies automatically (up to a

2.5% limit, and currently subject to a transition timetable) to

the UK exposures of firms incorporated in other European

Economic Area (EEA) states. The FPC expects it to apply also

to internationally active banks in jurisdictions outside the EEA

that have implemented the Basel III regulatory standards.

Consistent with this, recent CCyB actions by Czech Republic,

Hong Kong and Norway have been reciprocated.

5

0

5

10

15

2

000 02 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

Nominal GDP

growth rate

(b)

B

ank credit

(a)

Per cent

+

–

C

hart A Credit directly financed by the banking system

h

as grown broadly in line with nominal GDP over the

past two years

Growth in credit to households and firms compared with nominal

GDP growth

Sources: ONS and Bank calculations.

(a) Quarterly twelve-month growth rate of monetary financial institutions’ sterling net lending

to private non-financial corporations and households (in per cent) seasonally adjusted.

(b) Twelve-month growth rate of nominal GDP.

E

xecutive summary

vii

Box 2

Possible financial stability implications of the

United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the

European Union

In March 2017, the UK Government notified the European

Council of the United Kingdom’s intention to withdraw from

the European Union. This initiated, under Article 50 of the

Treaty on European Union, a two-year period for the

United Kingdom and the European Union to negotiate and

conclude a withdrawal agreement. The exit negotiations have

now begun.

As the FPC stated in September 2016, irrespective of the

particular form of the United Kingdom’s future relationship

with the European Union, and consistent with its statutory

responsibility, the FPC will remain committed to the

implementation of robust prudential standards in the UK

financial system. This will require a level of resilience to be

maintained that is at least as great as that currently planned

and which itself exceeds that required by international

baseline standards.

(1)

In addition, consistent with its statutory duty, the FPC will

continue to identify and monitor UK financial stability risks,

so that preparations can be made and action taken to

mitigate them.

There are a range of possible outcomes for the

United Kingdom’s future relationship with the European Union

and possible paths to that relationship. Consistent with its

remit, the FPC is focused on scenarios that, even if they may

be the least likely to occur, could have most impact on

UK financial stability. This includes a scenario in which there is

no agreement in place at the point of exit. Such scenarios are

where contingency planning and preparation will be most

valuable.

The Bank, FCA and PRA are working closely with regulated

firms and financial market infrastructures (FMIs) to ensure

they have comprehensive contingency plans in place. The FPC

will oversee contingency planning to mitigate risks to financial

stability as the withdrawal process unfolds.

Through this work, the FPC is aiming to promote an

orderly adjustment to the new relationship between the

United Kingdom and the European Union.

Without contingency plans that can be executed in the

available time, effects on financial stability could arise both

through direct effects on the provision of financial services,

and indirectly, through macroeconomic shocks that could test

the resilience of the financial system.

(1) Direct effects on the provision of financial services

A very large part of the United Kingdom’s legal and regulatory

f

ramework for financial services is directly or indirectly derived

from EU law. The United Kingdom’s financial services law

must therefore become domestic at the point of

withdrawal. The Government plans to execute this through

the Repeal Bill. Once enacted, this will ensure there is no legal

o

r regulatory vacuum in respect of financial services when the

United Kingdom leaves the European Union.

The European Union’s framework for financial services

establishes the right of financial companies within the

European Economic Area (EEA) to provide services across

national borders and to establish local branches in other

Member States without local authorisation.

This promotes substantial cross-border provision of a wide

range of financial services. Around £40 billion of UK financial

services revenues relate to EU clients and markets.

(2)

These

cross-border connections have resulted in more efficient

financial services for businesses and households across the

European Union.

There is no generally applicable institutional framework for

cross-border provision of financial services outside the

European Union. Globally, liberalisation of trade in services

lags far behind liberalisation of trade in goods. So without a

new bespoke agreement, UK firms could no longer provide

services to EEA clients (and vice versa) in the same manner as

they do today, or in some cases not at all. This creates two

broad risks. First, services could be dislocated as clients and

providers adjust. Second, the fragmentation of service

provision could increase costs and risks.

In the United Kingdom, the flow of new banking and

insurance services to UK customers could be disrupted if

EEA firms are unable to operate in the United Kingdom in

the same manner as they do today. Around 10% of the

outstanding stock of loans to private non-financial

corporations in the United Kingdom is extended by

UK branches of EEA banks.

(3)

Around 7% of general insurance contracts undertaken in the

United Kingdom and 3% of life insurance contracts are

written by EEA insurers.

(4)

As well as disrupting new business

from these providers, fragmentation could require the existing

contracts to be transferred to a UK-authorised firm in order to

address any legal uncertainties as to the status of, and ability

to perform, such contracts.

(1) www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2016/033.aspx.

(2) Source: Oliver Wyman, 2016.

(3) Source: Bank of England calculations.

(4) Sources: Firms’ published accounts, regulatory data and Bank calculations. Based on

premiums relating to insurance contracts.

v

iii Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

There could also be material dislocation of some services

supplied from the United Kingdom to the European Union.

EU clients would need to source substitute services from banks

and FMIs established in the EEA or other countries recognised

b

y the European Commission as ‘equivalent’. This is

particularly relevant to new debt and equity issuance and

derivatives business. These dislocations could also disrupt

the provision of services to UK clients who rely on EU

counterparties.

UK-located banks underwrite around half of the debt and

equity issued by EU companies.

(1)

EU companies could need

to find alternative providers of this service to sustain their

capital market issuance.

UK-located banks are counterparty to over half of the

over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives traded by

EU companies and banks.

(2)

To support EU-based derivatives

trading, substantial operational capacity may need to be

established in the European Union and additional capital and

balance sheet capacity would probably be needed.

Central counterparties (CCPs) located in the

United Kingdom provide services to EU clients in a range of

markets. The United Kingdom houses some of the world’s

largest CCPs. For example, LCH handles over 90% of

cleared interest rate swaps globally.

In addition to the potential disruption to new clearing business

for EU firms, if EU firms are unable to move their existing

derivatives contracts to EU authorised or recognised CCPs,

they would face capital charges that are up to ten times

higher. Moreover, to move a large stock of existing trades will

pose substantial and complex operational and legal

challenges.

In addition to the dislocation of services, fragmentation of

market-based finance could result in higher costs and

greater risks for both EU and UK companies and households.

Separation of derivatives clearing would reduce the benefits of

central clearing. It would impair the ability to diversify risks

across borders and, by increasing costs, reduce incentives for

firms to hedge risks. Industry estimates suggest that a single

basis point increase in cost resulting from splitting clearing of

interest rate swaps could cost EU firms €22 billion per year

across all of their business.

Delegation of asset management across borders is a

well-established practice. For example, 40% of the assets

managed in the United Kingdom are managed for overseas

clients; around half of this activity is on behalf of clients

outside Europe.

(3)

UK-located asset managers account for

37% of all assets managed in Europe.

(4)

If asset management

were to fragment between the United Kingdom and Europe,

material economies of scale and scope that are currently

achieved by pooling of funds and their management would be

reduced.

Together, these effects could increase the reliance of both

t

he UK and EU economies on their banking systems and

reduce the diversification and resilience of finance.

(2) Macroeconomic shocks that could test the resilience of

the financial system

To maintain consistent provision of financial services to the

UK economy, the financial system must be able to absorb

the impacts on their balance sheets of any adverse

economic shocks that could arise in some scenarios for the

United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union.

The Bank of England’s regular stress testing aims to ensure

that the banking system has the strength to withstand, and

continue to lend in, a broad and severe economic and market

shock.

The United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union

has the potential to affect the economy through supply,

demand and exchange rate channels.

(5)

The supply side of the economy could be disrupted by abrupt

increases in the costs of, or obstacles to, cross-border trade.

Demand could be impacted by the abrupt introduction of

restrictions on exports of financial and other services and

tariffs on trade in goods with the European Union. A reduction

in economic activity in high tax-paying sectors could affect

public finances and spending.

In some scenarios, heightened uncertainty could also reinforce

the existing risk of a fall in appetite of foreign investors for

UK assets. The United Kingdom relies on inflows of overseas

capital to finance its current account deficit — the excess of

investment over domestic saving. That deficit, which stood at

4.4% of GDP in 2016, is financed largely through direct

investment and portfolio investment in the form of long-term

debt and equity (Chart A).

A material reduction in the appetite of foreign investors to

provide finance to the United Kingdom would tighten

financing conditions for UK borrowers and reduce asset prices

(1) Based on Bank analysis of UK-located investment banks’ revenues in 2015 for M&A

and debt/equity issuance activities, using multiple sources.

(2) Based on Bank calculations and multiple sources, including Bank for International

Settlements triennial survey data (2016) which show UK-based dealers account for

82% of European trading in OTC single currency interest rate derivatives.

(3) Sources: Investment Association Annual Survey (2015–2016) and Bank calculations.

(4) Source: Investment Association Annual Survey (2015–2016).

(5) See the May 2017 Inflation Report;

www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/inflationreport/2017/may.pdf.

E

xecutive summary

ix

and investment. The effect could be most pronounced in

markets that have recently had greater reliance on access to

overseas capital, such as commercial real estate (CRE).

Around half of the investment in UK CRE since 2015 has been

financed by overseas investors (Chart B).

All else equal, economic shocks like these would probably

depress the exchange rate, putting upward pressure on

inflation. The combination of shocks could therefore possibly

create a more challenging trade-off for monetary policy. The

Monetary Policy Committee would have to make careful

judgements about the net effect of these influences on

demand, supply and inflation.

In these circumstances, the maintenance of financial stability

would require banks to be able to withstand, and continue

lending in, an environment of higher loan impairments,

increased risk of default on other assets, and lower asset prices

and collateral values.

Mitigating risks to financial stability

The FPC will continue to assess the resilience of the UK

financial system to adverse economic shocks that could arise.

The FPC will use the information from its regular stress testing

of major UK banks and building societies. These test banks’

resilience to a range of relevant scenarios, including a snap

back of interest rates, sharp adjustment in UK property

markets, and severe stress in the euro area.

The FPC will continue to assess the suitability of firms’

contingency plans for emerging risks, in the context of

progress on agreements and the continuity of the domestic

regulatory framework. This will draw on reviews by the Bank,

PRA and FCA of firms’ plans, including responses from banks,

insurers and designated investment firms to the PRA’s

April 2017 letter requesting that they summarise their

contingency plans for the full range of possible scenarios

following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the

European Union.

2

0

10

0

10

20

30

2011 12 13 14 15 16

Portfolio investment

(b)

F

oreign direct investment (FDI)

Other investment

(c)

Reserves and net derivatives

T

otal net inward financing flow

(d)

Current account deficit

+

–

Per cent of GDP

C

hart A The United Kingdom has relied on material

i

nflows of portfolio investment and FDI to finance its

current account deficit in recent years

Net inward financing flows

(a)

Sources: ONS and Bank calculations.

(

a) This is the change in UK foreign liabilities, less the change in UK foreign assets, for each

category of investment. These data are presented as annual series using four-quarter

averages.

(b) Portfolio investment consists of debt securities (including government debt), equities and

investment fund shares.

(c) Other investment consists mostly of loans and deposits.

(d) The total net inward financing flow is equal in magnitude to the current account deficit

(

plus errors and omissions).

0

5

1

0

15

2

0

25

2003 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

B

y overseas investors

B

y domestic investors

Total United Kingdom

£ billions

C

hart B Overseas investors have accounted for around

h

alf of total investment in UK CRE since 2015

UK CRE transactions (gross quarterly flows)

(a)

Sources: The Property Archive and Bank calculations.

(a) Final data points are the sum of three months to May 2017.

The FPC’s approach to addressing risks

from the UK mortgage market

P

art A

T

he FPC’s approach to addressing risks from the UK mortgage market 1

Summary

Buying a house is the biggest investment that many people

will make in their lives, and it is typically financed by debt.

In the United Kingdom, mortgages are households’ largest

liability and lenders’ largest loan exposure.

The FPC’s concern is with risks to the resilience of both

borrowers and lenders that arise from high levels of household

debt. While a significant factor contributing to high levels of

house prices relative to incomes in the United Kingdom has

been the relatively limited growth in the stock of housing, the

main drivers of housing supply are not under the control of the

Bank of England or the FPC. Consumer protection, meanwhile,

remains the responsibility of the FCA.

Historically, the build-up of mortgage debt has been a key

source of risk to financial and economic stability:

• Highly indebted households are more vulnerable to

unexpected falls in their incomes or increases in their

mortgage repayments.

• In an economic downturn, they do all they can to pay their

mortgages, but — as a result — may have to cut spending

sharply, making the downturn worse.

• In doing so, they also increase the risk of losses to lenders,

not just on mortgages, but on other lending too.

Build-ups of mortgage debt can be self-reinforcing. Lenders’

underwriting standards can turn quickly from responsible to

reckless:

• Housing is the main source of collateral in the real economy,

so higher house prices tend to lead to higher levels of

mortgage lending, feeding back into higher valuations.

• In an upturn, when risks are perceived to be low, lenders’

underwriting standards can loosen quickly, as they seek to

maintain or build market share. This increases the supply of

credit further.

To insure against these risks, in June 2014 the FPC introduced

a policy package, designed to prevent a significant increase in

the number of highly indebted households and a marked

loosening in underwriting standards. The two FPC

Recommendations were to:

• limit the proportion of mortgages extended at high

loan to income ratios; and

• promote minimum standards for how lenders test

affordability for borrowers.

These measures were not expected to restrain housing market

activity unless lenders’ underwriting standards eased. They

were put in place as insurance and complement the annual

stress tests of major lenders, which test that lenders can

withstand sharp economic downturns, including large falls in

house prices, while also continuing to lend.

The FPC views its Recommendations as likely to remain in

place for the foreseeable future. It judges that their benefits

would increase if they became more binding relative to

lenders’ underwriting standards. The FPC will continue to

review their calibration on a regular basis.

The FPC has clarified its affordability test Recommendation to

ensure consistency in its application across lenders. The

Committee has recommended that:

• When assessing affordability, mortgage lenders should apply

an interest rate stress test that assesses whether borrowers

could still afford their mortgages if, at any point over the

first five years of the loan, their mortgage rate were to be

3 percentage points higher than the reversion rate specified

in the mortgage contract at origination.

This Recommendation can alternatively be interpreted as

introducing a ‘safety margin’ between current mortgage

payments and current income, also ensuring that the

household sector as a whole is better able to withstand

adverse shocks to income and employment.

The housing market can be a key source of risk to

financial stability

Housing accounts for nearly half of the total assets of

UK households. And around two thirds of house purchases are

financed by mortgage debt.

Housing has been at the heart of many financial crises. Since

the 1950s, there has been a material rise in mortgage debt

across advanced economies, driving a major expansion of the

balance sheet of the financial sector. More than two thirds of

the 46 systemic banking crises for which house price data are

2

Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

available were preceded by housing boom-bust cycles.

(1)

Mortgage booms have also tended to be followed by periods

of considerably slower economic growth than non-mortgage

credit booms, irrespective of whether a financial crisis

o

ccurred or not.

(

2)

Mortgages are the largest liability of UK households.

They can be a source of risk for borrowers’ resilience and

broader economic activity.

Over the past 20 years, house prices have risen significantly

relative to incomes, so households have to borrow more to

buy a house. The resulting high levels of household debt

expose the UK economy to the risk of sharp cuts in

consumption in the face of shocks to income or interest

rates.

A significant factor contributing to high levels of house prices

relative to incomes in the United Kingdom (Chart A.1)

(3)

has

been the relatively limited growth in the stock of housing. The

absolute level of house prices may further reflect a protracted

decline in interest rates.

Over the past 50 years, the number of new houses built each

year in the United Kingdom has more than halved, from a peak

of 426,000 in 1968 (Chart A.2). Since 1982, this number has

averaged less than 190,000, while the UK population has

increased by around 265,000 per year.

(4)

Partly as a result, the

cost of renting a property — as well as buying it — can be high

relative to household incomes in parts of the country. In the

2016 NMG survey, around one third of respondents who lived

in rented accommodation reported that their rental payments

were 30% or more of their pre-tax incomes. The main drivers

of housing supply are not under the control of the Bank of

England or the FPC, and are partly related to the planning

system.

(5)

Long-term real interest rates have been declining across

advanced economies for several decades. Global structural

factors — such as demographics — are likely to have been the

primary driver of these falls, which have contributed to a rise

in the level of house prices.

(6)

In recent months, annual house

price inflation has weakened; in May 2017 house prices rose at

the slowest annual rate since May 2013.

(7)

But while

respondents to the RICS survey in May 2017 expected the

slowdown to continue in the near term, they expected prices

to rise over the next year.

Building up a deposit to buy a house has become more

difficult. The average house price for first-time buyers

increased from around £50,000 in 1997 to over £200,000 in

2016. Over the same period, the size of a typical deposit for a

first-time buyer increased from less than £5,000 to over

£30,000. The Wealth and Assets Survey

(8)

suggests that only

(1) Crowe, C, Dell’Ariccia, G, Igan, D and Rabanal, P (2011), ‘How to deal with real estate

booms: lessons from country experiences’, IMF Working Paper 11/91;

www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp1191.pdf.

(2) See Jordà, O, Schularick, M and Taylor, A M (2014), ‘The great mortgaging: housing

finance, crises and business cycles’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working

Paper 2014–23;

www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2014-23.pdf.

(3) The national average masks regional differences. At end-2015, the house price to

household income ratio was 3.5 in the North of England and 6.2 in London, and

averaged 4.2 for the United Kingdom.

(4) Over 1981–2016, the size of the average UK household has also fallen, incrementing

the pressure from population growth. For evidence on the impact of supply on

affordability, see Hilber, C A L and Vermeulen, W (2015), ‘The impact of supply

constraints on house prices in England’;

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ecoj.12213/abstract.

(5) For more details see Barker, K (2004), Review of housing supply;

https://web.archive.org/web/20080513212848/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/

consultations_and_legislation/barker/consult_barker_index.cfm#report and

Hilber, C A L and Vermeulen, W (2015), op cit.

(6) See the box ‘Explaining the long-term decline in interest rates’ on pages 8–9 of the

November 2016 Inflation Report; www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/

Documents/inflationreport/2016/nov.pdf and the box ‘The long-term outlook for

interest rates’ on pages 6–7 of the May 2017 Inflation Report;

www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/inflationreport/2017/may.pdf.

(7) Based on the average of the Halifax and Nationwide house price indices.

(8) The Wealth and Assets Survey is a household survey that gathers information on,

among other things, level of savings and debt, saving for retirement, how wealth is

distributed across households and factors that affect financial planning.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1973 78 83 88 93 98 2003 08 13

House price to household income

Ratio

Chart A.1 UK house prices have risen significantly

relative to households’ incomes

UK house price to household income ratio

(

a)(b)

Sources: Department for Communities and Local Government, Halifax, Nationwide, ONS and

Bank calculations.

(a) The ratio is calculated as average UK house price divided by the four-quarter moving sum of

gross disposable income of the UK household and non-profit sector per household.

Aggregate household disposable income is adjusted for financial intermediation services

indirectly measured (FISIM) and changes in pension entitlements.

(b) House price is an average of the Halifax and Nationwide indices.

0

50

1

00

150

200

2

50

3

00

350

4

00

450

1952 62 72 82 92 2002 12

C

ompletions of new dwellings

Thousands

C

hart A.2 Over the past 50 years, the number of houses

b

uilt each year has more than halved

Completions of new dwellings in the United Kingdom

(a)

Sources: Department for Communities and Local Government and Bank calculations.

(a) Total number of permanent dwellings completed in the United Kingdom per calendar year.

I

ncludes completions from private enterprises, housing associations and local authorities.

Data for 2016 Q4 and 2017 Q1 assume that completions of new dwellings in the

United Kingdom as a whole have grown in line with those in England. The diamond shows

the 2017 Q1 outturn on an annualised basis for 2017. Data are seasonally adjusted.

P

art A

T

he FPC’s approach to addressing risks from the UK mortgage market 3

around 6% of renters aged 45 or younger have financial assets

worth £30,000 or more, and that only 11% have £15,000 or

more.

T

he increase in house prices relative to incomes in recent

decades has contributed to a rise in UK household

indebtedness, which is currently high by historical

standards. Since the late 1980s, the outstanding stock of

mortgage debt has nearly doubled and represents the majority

of the aggregate household debt to income (DTI) ratio

(Chart A.3).

During the financial crisis, countries that had initially higher

levels of household debt relative to income saw larger falls in

aggregate consumption (Chart A.4), putting downward

pressure on broader economic activity. Analysis of

household-level data also suggests that individual households

with higher mortgage debt relative to income adjust spending

more sharply in response to shocks. For example, data from

the Living Costs and Food Survey show that, during the

financial crisis, the fall in consumption relative to income

among UK households with loan to income (LTI) ratios above

four was around three times larger than the fall for those with

ratios between one and two (Chart A.5). Econometric studies

confirm these results, even after controlling for other

household characteristics.

(1)

Given the ‘full-recourse’ nature of UK mortgage contracts,

borrowers in the United Kingdom typically do all they can

to pay their mortgages rather than default, including

cutting back sharply on spending. In the United Kingdom, if

a borrower defaults on a mortgage and the value of the house

does not cover the outstanding mortgage, the lender has a

claim against other assets of the debtor. This contrasts with

some other jurisdictions, such as the United States, where

‘non-recourse’ mortgages are more widespread.

(1) See Bunn, P and Rostom, M (2015), ‘Household debt and spending in the

United Kingdom’, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 554;

www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/workingpapers/2015/swp554.pdf.

0

20

40

60

80

1

00

1

20

140

160

91 95 99 2003 07 11 15

P

er cent

1987

Household debt to income ratio (excluding mortgages)

H

ousehold debt to income ratio (of which mortgages)

Total household debt to income ratio

Chart A.3 UK household indebtedness is high by

historical standards

UK household debt to income ratio

(

a)(b)(c)(d)

Sources: ONS and Bank calculations.

(a) Total household debt to income ratio is calculated as gross debt as a percentage of a

four-quarter moving sum of gross disposable income of the UK household and non-profit

sector. Includes all liabilities of the household sector except for unfunded pension liabilities

and financial derivatives of the non-profit sector.

(b) Mortgage debt to income ratio is calculated as total debt secured on dwellings as a

percentage of a four-quarter moving sum of disposable income.

(c) Non-mortgage debt is the residual of mortgage debt subtracted from total debt.

(d) The household disposable income series is adjusted for FISIM and changes in pension

entitlements.

10

8

6

4

2

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

0100200300400

H

ousehold debt to income ratio in 2007, per cent

United Kingdom

Adjusted consumption growth 2007–12, per cent

+

–

C

hart A.4 Countries with higher levels of household

d

ebt relative to income saw larger consumption falls in

the crisis

Household debt to income ratio and consumption growth over

2007–12

(a)

S

ources: Flodén (2014) and OECD National Accounts.

(a) Change in consumption is adjusted for the pre-crisis change in total debt, the level of total debt

and the current account balance. See Flodén, M (2014), ‘Did household debt matter in the

Great Recession?’, available at http://martinfloden.net/files/hhdebt_supplement_2014.pdf.

25

20

15

10

5

0

0 to 1 1 to 2 2 to 3 3 to 4 ≥4

P

ercentage point change in consumption to income ratio

Mortgage LTI ratio

–

Chart A.5 UK households with higher levels of mortgage

debt relative to income adjusted spending more sharply

during the crisis

Change in consumption relative to income among mortgagors

with different LTI ratios between 2007 and 2009

(a)(b)(c)

Sources: Living Costs and Food (LCF) Survey, ONS and Bank calculations.

(a) Change in average non-housing consumption as a share of average post-tax income (net of

mortgage interest payments) among households in each mortgage LTI category between

2007 and 2009.

(b) LCF Survey data scaled to match National Accounts (excluding imputed rental income,

income received by pension funds on behalf of households and FISIM). LTI ratio is calculated

using secured debt only as a proportion of gross income.

(c) Repeat cross-section methodology used, with no controls for other factors, or how

households may have moved between LTI categories between 2007 and 2009.

4

Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

Given the prevalence of short-term fixed-rate mortgage

contracts, UK households are also particularly exposed to

the risk of unexpected changes in interest rates.

(1)

Almost

80% of new mortgage lending in 2016 was either on a fixed

r

ate for a period of less than five years or on a floating rate.

In summary, mortgage debt can be a source of risk for

borrowers’ ability to weather downturns without substantial

cutbacks in their spending. UK household indebtedness is

high, which can be a threat to the wider economy. Highly

indebted households can cut back sharply on spending in

response to adverse shocks to incomes or interest rates,

putting downward pressure on economic activity and reducing

the resilience of the financial system.

Mortgages are the largest loan exposure for UK lenders.

They can be a source of risk for lenders’ resilience,

impairing the provision of credit.

In a severe downturn, some borrowers will be unable to

repay their mortgages even after cutting back on spending,

for example, in the event of a rise in unemployment. The

resulting defaults can affect lenders’ resilience, with

mortgages accounting for around two thirds of major

UK banks’ loans to UK borrowers.

(2)

The proportion of households experiencing repayment

difficulties can rise sharply as the share of income spent on

servicing mortgage debt — also known as the mortgage

debt-servicing ratio (DSR) — increases beyond a certain level

(Chart A.6). Both the average DSR of the UK household

sector as a whole and the proportion of households with high

mortgage DSRs have fallen since the crisis, supported by the

low level of interest rates. But households’ ability to service

their mortgage debt could be challenged by either a rise in

mortgage rates or a fall in incomes. As an illustration, Bank

staff estimate that in the event of a rise in unemployment to

8%, the proportion of households with high DSRs would

double, reaching a level close to that seen in 2007 (Chart A.7).

During the global financial crisis, loss rates on mortgages were

contained, reflecting the sharp fall in interest rates and a rise

in unemployment that was relatively modest given the fall in

economic activity.

(3)

But in the 1990s recession, which was

marked by a significant rise in interest rates and

unemployment, loss rates were more material.

(4)

And results

from stress tests of major UK banks suggest that they could

reach similar levels in future periods of severe stress (Chart

A.8), particularly if house prices were to fall significantly,

increasing lenders’ losses in the event of borrower default.

Significant falls in house prices are highly correlated with

economic downturns, when borrowers are also more likely to

become unemployed and default on their mortgages. In such

a severe stress, lenders are likely to incur larger losses on

lending originally extended at high LTV ratios. This is because

such mortgages are more likely to experience ‘negative equity’

in the event of a fall in house prices, meaning that the value of

the housing collateral will be less likely to cover the mortgage

loan.

0

4

8

12

16

2

0

0

–5 5–10 10–15 15–20 20–25 25–30 30–35 35–40 40–50 50+

NMG survey

(2014–15, arrears 2 months+)

Wealth and Assets Survey

(2010–12, arrears 2 months+)

P

ercentage of mortgagors in arrears

(a)

Mortgage DSR, per cent

C

hart A.6 Households with high debt-servicing ratios

(

DSRs) are more likely to experience repayment difficulties

Households in two-month arrears by mortgage DSR

Sources: NMG Consulting survey, Wealth and Assets Survey and Bank calculations.

(a) The share of mortgagors who have been in arrears for at least two months. The mortgage

DSR is calculated as total mortgage payments (including principal repayments) as a

percentage of pre-tax income. Calculation excludes those whose DSR exceeds 100%.

R

eported repayments may not account for endowment mortgage premia.

(1) This has been a feature of the UK mortgage market for many years and was discussed

in Miles, D (2004), The UK mortgage market: taking a longer-term view;

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20071204181447/hm-

treasury.gov.uk/consultations_and_legislation/miles_review/consult_miles_index.cfm.

(2) Unless otherwise stated, ‘banks’ or ‘lenders’ refer to all UK banks and building

societies.

(3) The distribution of unemployment was also skewed towards younger households,

among whom the owner-occupier rate is lower.

(4) Less developed credit scoring and credit risk management practices relative to today

also help explain the high loss rates in the early 1990s.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

1991 96 2001 06 11 16

P

ercentages of households

Households with mortgage DSR ≥ 40%

— unemployment at 8%

Households with mortgage DSR ≥ 40% (BHPS/US)

Households with mortgage DSR ≥ 40% (NMG)

Chart A.7 An increase in unemployment could double the

proportion of vulnerable households

Percentage of households with mortgage debt-servicing ratios of

40% or greater

(

a)(b)(c)

Sources: British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), NMG Consulting survey, ONS, Understanding

Society (US) and Bank calculations.

(a) Mortgage DSR calculated as total mortgage payments as a percentage of pre-tax income.

(b) Percentage of households with mortgage DSR above 40% is calculated using British

Household Panel Survey (1991 to 2008), Understanding Society (2009 to 2013), and

NMG Consulting survey (2011 to 2017).

(c) A new household income question was introduced in the NMG survey in 2015. Data from

2011 to 2014 surveys have been spliced on to 2015 data to produce a consistent time series.

Data for 2017 come from the spring survey, while data from previous years come from the

autumn survey.

P

art A

T

he FPC’s approach to addressing risks from the UK mortgage market 5

The provision of high LTV lending has increased from its

post-crisis lows recently, but both the annual average total

volume of high LTV lending and its share of total mortgage

lending remain lower than at any point between 1982 and

2008 (Chart A.9). At the same time, LTV ratios for

outstanding loans have fallen as a result of house price growth

and mortgagors repaying existing debt. As a result, for

example, only 2% of the major six lenders’ stock of mortgages

had an LTV above 90% at end-2016 (Chart A.10).

High mortgage debt can also affect lenders’ resilience

indirectly. In a downturn, highly indebted households

prioritising mortgage payments may default on their other

credit commitments, such as credit cards or personal loans.

Sharp cuts in consumption that amplify the downturn can also

lead to credit losses on other types of lending, for example

loans to businesses.

Overall, in a severe stress, high levels of mortgage debt could

lead to significant losses (both directly and indirectly) and

reduce the resilience of lenders, impairing the provision of

credit to the real economy and further intensifying an

economic downturn.

Self-reinforcing feedback loops between levels of

mortgage lending and house prices can amplify risks to

both borrowers and lenders.

Housing is the main source of collateral in the real

economy, so higher house prices tend to lead to higher

levels of mortgage lending, feeding back into higher

valuations. As valuations increase, rising wealth for existing

homeowners and higher collateral values for lenders can

increase both the demand for, and supply of, credit, leading to

a self-reinforcing loop between levels of mortgage lending and

house prices. Expectations of future house price increases can

also prompt prospective buyers to bring forward house

purchases. The resulting rapid growth in mortgage lending can

amplify risks to both lenders and borrowers.

0.0

0.5

1

.0

1

.5

2.0

2

.5

3.0

1991–95 2009–13 2014 stress

test

2015 stress

test

2016 stress

test

P

er cent

Cumulative five-year loss rates

E

stimated loss rates incurred by insurers

C

hart A.8 Loss rates on UK mortgages could reach

m

aterial levels in a severe stress

Cumulative five-year loss rates on UK mortgages in past

downturns and in stress tests

(a)(b)(c)(d)(e)

Sources: Acadametrics, Bank of England, lenders’ stress-testing submissions and

Bank calculations.

(a) Cumulative loss rates are calculated as cumulative losses divided by average balances.

(b) Losses defined as write-offs for the 1991–95 and 2009–13 periods and impairment charges

for stress-test results.

(c) 1991–95 write-offs include all banks and building societies and an estimate of the losses

borne by the UK insurance industry on loans originated by banks and building societies.

Based on data published by MIAC-Acadametrics.

(

d) Losses in 2009–13 and stress tests include the six major lenders.

(e) Impairments in the 2014 stress test are cumulative over three years.

0

50

100

150

2

00

250

3

00

3

50

400

10

20

3

0

40

50

60

83 87

9

1

95

9

9 2003

07 11

1

5

Percentage of mortgages

N

umber of mortgages (thousands)

1

979

0

Completions <90% LTV (right-hand scale)

Completions ≥90% LTV

(d)

(right-hand scale)

P

roportion ≥90% LTV (left-hand scale)

(e)

C

hart A.9 High LTV mortgage lending remains lower

t

han at any point between 1982 and 2008

New mortgage lending by LTV at origination

(a)(b)(c)

Sources: Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML), FCA Product Sales Database (PSD) and

Bank calculations.

(a) Data are shown as a four-quarter moving average.

(

b) Data include loans to first-time buyers, council/registered social tenants exercising their right

to buy and home movers.

(c) The PSD includes regulated mortgage contracts only.

(d) The number of mortgage loans with ≥90% LTV is calculated using the aggregate number of

mortgages from the CML and the proportion of mortgages with ≥90% LTV from the PSD.

(e) PSD data are only available since 2005 Q2. Data from 1993 to 2005 are from the Survey of

Mortgage Lenders, which was operated by the CML, and earlier data are from the 5% Sample

S

urvey of Building Society Mortgages. The data sources are not directly comparable: the

PSD covers all regulated mortgage lending whereas the earlier data are a sample of the

mortgage market. Data for the first three quarters of 1992 are missing, chart values are

interpolated for this period.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Per cent of mortgage book

2009

0% < LTV ≤ 50%

50% < LTV ≤ 75%

75% < LTV ≤ 90%

90% < LTV ≤ 95%

95% < LTV ≤ 100%

100% and above

Chart A.10 The LTV distribution of the stock of

mortgages has improved since the crisis

UK mortgage books by indexed LTV

(

a)

Sources: PRA regulatory returns and Bank calculations.

(a) Peer group accounts for around 74% of total UK mortgages and includes the major

UK lenders.

6

Financial Stability Report

J

une 2017

In an upturn, when risks from credit losses are perceived to

be low, the underwriting standards lenders apply to decide

on what terms to lend can deteriorate quickly as they seek

to maintain or build market share. This increases the

s

upply of credit further. Underwriting standards on

UK mortgages weakened in the lead-up to the financial crisis,

contributing to the growth in mortgage lending and house

prices. Across a range of metrics, underwriting standards are

now more robust relative to the period before the crisis. But

market contacts suggest that lending conditions in the

mortgage market are becoming easier and competitive

pressures in the mortgage market remain. Mortgage spreads

over risk-free rates have fallen materially since their peak

in 2012 (Chart A.11). Lenders are also extending an increasing

proportion of mortgages without fees. Forty-six per cent

of mortgages were extended without fees in the first part

of 2017, compared to 37% in 2016 and just 12% in 2011

(Chart A.12).

A similar feedback loop between house prices and credit also

arises in a downturn. An economic slowdown can reduce

house prices. Due to the role of housing as collateral, lower

house prices reduce the demand for, and supply of, credit.

Expectations of further price reductions, which can result in

sales of houses at heavily discounted prices (‘fire sales’), can

further amplify house price falls, reinforcing the adverse

feedback loop. The resulting deterioration in borrowers’

and lenders’ resilience will intensify a downturn

(Figure A.1).

Growth in the private rental sector in recent years may

have led to growing risks of amplified house price cycles

from leveraged buy-to-let investors.

(1)

The share of

households in the private rental sector rose from around 10%

in 2002 to 20% in 2016. Buy-to-let investors do not live in

the house that they rent out and their behaviour is more likely

to be driven by their expected returns on their housing

investment than that of owner-occupiers. But if either house

prices or the income received from rental payments were to

fall materially, there is a risk that some leveraged investors

may look to sell their properties quickly, reinforcing house