Care Planning Guide

Achieving Best Life Experience

Sunn

ybrook

VETERANS

Restoring Abilities

After a Stroke

3

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Acknowledgments

This Care Planning Guide was written by:

Dr. Jocelyn Charles MD CCFP MScCH

Medical Director, Veterans Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Associate Professor, Department of Family & Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto

Pearl Gryfe MSc BSc OT

Clinical & Managing Director Assistive Technology Clinic, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Adjunct Lecturer, Dept. of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy,

Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto

Selena Sun BSc PT

Physiotherapist, Veterans Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Chris Watson MHSc SLP(C) Reg. CASLPO

Speech-Language Pathologist, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Kristen Paulseth MHSc SLP(C) Reg. CASLPO

Speech-Language Pathologist, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Cecilia Yeung RN MN GNC(C) IIWCC

Advanced Practice Nurse

Adjunct Lecturer, Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto

With the input and assistance of the K1 Centre Care Team

We acknowledge the Heart & Stroke Foundation for sharing their educational resources referred to in this guide

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke:

Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE)

Care Planning Guide

Veterans Centre

2012

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Responding to Behaviours Due to Dementia using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

4

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

GREETINGS FROM THE VETERANS CENTRE’S DIRECTORS

We are very pleased to launch this exciting series of Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care

Planning Guides to assist our interprofessional staff, our Veteran residents and their families in working

together for the best possible quality of life for our residents.

While traditional care focuses on achieving the best clinical outcomes using accepted scientic

evidence and traditional practice methods, our ABLE philosophy focuses on planning care with the

resident and family to achieve what the resident considers to be his or her best life experience in

the Veterans Centre. This involves integrating scientic evidence, the resident’s current abilities and

potential for improvement and the resident’s desired life experience. This collaborative care planning

welcomes and promotes creativity through understanding and sharing of perspectives and ideas.

The ABLE Care Planning Guides are intended for use beyond Sunnybrook’s Veterans Centre. It is

our hope that our ABLE guides will provide interprofessional staff working in complex continuing care

facilities and nursing homes with an easily accessible resource to use with residents and families in

planning and delivering care that is focused on what is important to each resident. We wish you a

successful implementation!

Dorothy Ferguson, RN, BScN, MBA Jocelyn Charles, MD, CCFP

Director of Operations Medical Director

Veterans Centre Veterans Centre

5

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 6

COMPONENT 1

ASSESS AND DOCUMENT ABILITIES 8

COMPONENT 2

IDENTIFY POTENTIAL FOR IMPROVED FUNCTION 15

COMPONENT 3

LISTEN TO THE VOICE OF THE RESIDENT 18

COMPONENT 4

CARE PLANNING TO ACHIEVE RESIDENT’S DESIRED LIFE EXPERIENCE 21

COMPONENT 5

INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE ADVERSE OUTCOMES 34

COMPONENT 6

MONITORING THE RESIDENT’S RESPONSE TO INTERVENTIONS 47

DEFINITIONS 49

APPENDICES

APPENDIX 1

UNDERSTANDING STROKE 52

APPENDIX 2

SAFE TRANSFERS 55

APPENDIX 3

ENSURING HYDRATION AND NUTRITION 57

APPENDIX 4

SUGGESTED POST-STROKE EXERCISES 60

Appendix 5

REFERENCES 63

6

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

66

INTRODUCTION

At the Veterans Centre at Sunnybrook Health Sciences

Centre, our goal is to help each Veteran live according to

his or her preferences and to enjoy the best life experience

possible. While traditional best practice and clinical guidelines

focus on best clinical outcomes, in long term care (LTC) our

focus is on quality of life and helping residents perform his

or her desired activities. We encourage inter-professional

collaboration and teamwork focused on the resident’s goals.

Stroke is one of the most common causes of acquired

disability in the aged population and can be an overwhelming,

life-altering event. Approximately 20 per cent of residents

in LTC have a primary diagnosis of stroke. Many of these

residents have not had the opportunity to improve and

restore function. The goal of this guide is to help staff make

a difference in the lives of these residents by working with

them to restore the abilities that will allow them to achieve

their desired life experiences.

Traditional stroke rehabilitation involves evidence-based

assessment and treatment by a variety of health care providers

focused on achieving the highest possible independent

physical and psychological functioning. A signicant number of

long term care residents are not eligible for stroke rehabilitation

programs due to frailty, the severity of their decits, and/or

other physical and cognitive limitations. However, many can

benet from the approach outlined in this guide, even years

after a stroke.

This guide outlines a restorative care approach which respects

each resident’s individuality, and encourages listening to the

resident’s desired outcomes, attends to the resident’s physical

comfort and provides emotional support. Each resident has

his or her own unique values, preferences and needs. Care

should be consistent with the resident’s needs and how the

resident prefers to be assisted.

Written to help staff from any discipline nd information

quickly and easily, this guide is a resource to help caregivers

assist residents achieve their best possible quality of life and

life experience.

7

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

ABLE CARE GOAL-SETTING FRAMEWORK

ABLE CARE GOAL-SETTING FRAMEWORK

What is

preventing the

resident from

achieving these

goals?

Identify

interprofessional

strategies to

facilitate

achieving life

experience goals

Communicate &

implement

strategies

Establish realistic

goals to achieve

desired life

experience

How can we help

to enable the

resident to

achieve goals?

Share

assessments

with resident

/family

- Abilities

- Potentials

What would be

the ideal life

experience for

this resident in

the Veterans

Centre?

Identify current

abilities &

potential for

improved/

enhanced

abilities

Assess potential

for participation

in meaningful

leisure activities

Identify

limitations to

function

Assess verbal &

nonverbal

communication

skills

Assess cognition

Assess physical

abilities (motor,

sensory, pain,

cormorbid health

conditions)

Assess

psychological,

emotional & spiritu

al

needs

ASSESS

RESIDENT’S

ABILITIES &

NEEDS

ESTABLISH

LIFE

EXPERIENCE

GOALS

CREATE &

IMPLEMENT

STRATEGIES

TO ACHIEVE

GOALS

LISTEN TO

THE VOICE

OF THE

RESIDENT

IDENTIFY

POTENTIAL FOR

IMPROVED

FUNCTION &

QOL*

MONITOR

OUTCOMES

Observe

response to

interventions

Modify

interventios

based on

response

Periodic review

of abilities and

goals

*QOL = Quality of Life

8

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 1

ASSESS AND DOCUMENT ABILITIES

A stroke can affect a resident’s function in many ways. The brain controls all of our physical and mental functioning as

well as our emotions and social abilities. How a stroke impacts a resident depends on the part of the brain affected by

the stroke as well as the resident’s previous level of functioning, physical and mental health, personality, environment

and coping strategies. (See Appendix 1) Appropriate interventions through a restorative care approach

1

can lead to

signicant improvements in recovery and functioning even years after a stroke.

Describe Resident’s Current Function

The rst step is to understand a resident’s current limitations to physical, psychological and cognitive functioning.

Accurate recognition of functional impairments can allow for individualized restorative interventions which help reduce

permanent decits and improve a resident’s quality of life.

STEP 1: Describe General Appearance

Observe and document:

• Level of alertness

• Signs of discomfort or pain

• Ability to speak

• Ability to comprehend or understand

• Paralysis or paresis on one side

• Apathy or low motivation

• Frustration and/or irritability

• Specic verbal, non-verbal and/or physical behaviours. (Refer to ABLE Care Planning Guide: Responding to

Behaviours Due to Dementia.)

• Fluctuations in function or behaviours

• Possible barriers to functioning – communication, mobility, cognition

9

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

STEP 2: Describe Ability to Communicate

Difculties with communication may arise from a stroke affecting many different parts of the brain. In general, though, residents

who have had a stroke on the left side of the brain tend to have signicant difculties with communication. To plan appropriate

interventions to improve communication, start by to observing and documenting the resident’s current communication skills.

When documenting communication, only use the term “non-communicative” when the resident has no ability to communicate,

either verbally or non-verbally. Do not use nondescriptive or judgmental terms, such as “speaks funny,” “speaks nonsense”

or “incomprehensible.” Also, avoid labeling; for example, “demented.”

Components of Communication Assessment

Awareness of ability to

communicate

• Perceives communication difculties?

• Frustrated by communication difculties?

Ability to understand

(comprehend)

• Ability to respond reliably to simple yes/no questions (eg: name, season,

location)

• Ability to follow simple one-step commands, multi-step commands

• Ability to understand conversational speech

• Ability to understand more complex material (humor, information not related to

the immediate environment)

Ability to express

• Does spontaneous speech consist of full sentences, or single words?

• Is spoken message on-topic?

• Does spoken message contain non-existent or incorrect words?

• Ability to name objects, people

• Ability to repeat single words, sentences

Quality of speech

• Ability to produce voice

• Strength or volume of voice

• Quality of voice (hoarse, breathy, nasal, strained)

• Clarity of speech (clear, or slurred)

• Rate and rhythm of speech (fast and rushed, slow and laborious)

Written language skills

• Ability to write their name, letters, numbers, single words, sentences, and

paragraphs

• Ability to read single words, sentences, or paragraphs

Non-verbal language skills

• Level of engagement in the conversation: do they maintain eye contact, take

appropriate turns when speaking

• Responds to, or use facial expression to communicate?

• Responds to, or use gestures to communicate

10

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 1

STEP 3: Describe Motor Abilities

The ability to move after a stroke is affected by the resident’s pre-

stroke level of functioning, the type and extent of the stroke as

well as the degree of restorative care provided after the stroke.

Assessing the resident’s degree of limb and trunk mobility and

functional mobility provides the basics for understanding limitations

to enhanced function.

Describe abilities

Limb Mobility:

• Is the resident able to lift his or her affected limb up against gravity? Describe effort

required: minimal, moderate or maximal.

• Describe the degree of limb movement with and without assistance: passive and active

range of motion, full range or partial range for all the affected joints.

• Is there any pain with movement of the limbs, especially the shoulder?

Functional Mobility:

Ability to Roll:

• Is the resident able to roll from side to side independently? Describe assistance: use of

bed rail; one person assistance (minimal or moderate) or two person assistance.

• Is cueing needed for the affected limb?

Ability to sit up at

the edge of the bed:

• Is the resident able to get him/herself up to sit at the edge of the bed?

• Describe assistance needed cueing: minimal, moderate, maximal.

• Does he or she need to use a transfer pole or bed rail to move?

• Can he or she sit at the edge of the bed unsupported? With assistance?

• Does he or she lean to one side?

• How long can they sit at the edge of the bed?

Ability to sit in a

manual wheelchair:

• Can the resident sit comfortably in a manual wheelchair?

• Does he or she lean to one side or lean/fall forward?

• How long can he/she sit up in a wheelchair?

• Is support needed on the stroke limb when seated?

• Can the resident shift his/her weight or reposition him/herself independently in the

wheelchair?

• Is the resident able to move independently in the wheelchair?

• Is the resident able to use a power wheelchair safely?

11

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Describe abilities

Ability to stand up:

• Describe assistance needed: minimal, moderate, maximal.

• Need for gait aid to stand.

• Describe his/her posture: are the resident’s shoulders, hips and feet aligned and parallel?

Are they able to weight bear well on both legs?

• Can he/she stand unsupported? Describe the assistance needed for the resident to

remain standing (minimal/moderate/maximal)?

• Is a walker/pole needed for resident to stay standing?

• How long can he/she stand for?

Ability to walk:

• Can the resident weight bear well on the stroke leg or does that knee buckle?

• Can the resident take a normal step?

• How far can he/she walk?

• How much assistance is needed when walking: Supervision, Minimal, Moderate or

Maximum?

• Does the resident need a gait aid when walking? i.e. walker (with wheels), rollator?

Ability to Transfer:

• Is the resident able to follow directions safely for a safe transfer?

• Does the resident have good trunk control when sitting?

• Does the resident have good strength for weight bearing when standing?

• Is a transfer device needed i.e. transfer pole/walker?

Limitations to

Mobility:

• What is the resident’s energy level? Appears

fatigued? Are they too drowsy? Falling asleep

easily?

• Are there environmental obstacles to movement?

• Cognition: is resident able to follow directions

for safe mobility? Does the resident make

impulsive movements?

• Strength: does resident have enough strength

for safe mobility?

• Is there evidence of pain with movement:

grimacing, groaning, holding a specic body area,

limping, etc?

• Are aids/devices needed for safe transfers i.e.

transfer pole, sliding board, bed rails?

• Are aids/devices needed for mobility: walker, wheelchair, cane?

12

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 1

STEP 4: Describe Perception of His or Her Environment

Understanding the perceptual challenges a resident is experiencing will enable you to identify strategies to overcome these

challenges and help the resident achieve his or her goals. Perception encompasses how one processes and interprets

information from one’s surroundings. In addition to referring to the ability to see, hear, feel and taste, perception includes an

awareness of time, an awareness of the location of objects in relation to each other (spatial relations), an awareness of his

or her body position in space (proprioception), and the ability to recognize familiar people, places and objects.

After a stroke, a person’s ability to feel, sense temperature and be aware of his or her body position can decrease or be

absent. Following a stroke on the right side of the brain, an individual may experience neglect of his or her affected side.

This individual can then unknowingly injure him or herself on the affected side. To identify neglect, you may nd it useful to

use the mnemonic “tune-in.”

A Mnemonic to Identify Neglect

T

Turning the head and/or eyes to one side and not spontaneously looking the other way

U

Unaware of where an arm and/or leg is in relation to the rest of the body

N

Neglecting one side of the body, as if it doesn’t exist

E

Evidence of repeated trauma to the affected limb, but individual is unaware of these injuries

I

Ignoring food on one side of the plate

N

Not able to distinguish temperature (hot/cold) on the affected side

13

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

STEP 5: Describe Mood and Behaviours

When a person has a stroke, the health care team initially focuses on the physical effects of the stroke. However, the

individual may also experience fear, anger, sadness, anxiety, frustration and a sense of grief over his or her physical and

mental losses. All of these emotions result in behaviour changes. Understanding some of the contributing factors to these

behaviour changes will help you plan appropriate care strategies.

The time following a stroke can be an emotional rollercoaster, with the individual experiencing a wide range of feelings – from

loss and despair, to hope, anger and resigned acceptance. In addition, a stroke can affect an individual’s ability to control

his or her emotions, resulting in emotional lability or marked uctuations in emotions.

Residents who have suffered a stroke are at high risk for depression, which may present as cognitive decline. On admission,

the clinical team should assess the resident’s prior history of depression and previous risk factors for depression. In addition,

the team should assess for depression every three months. Treating this mood disorder with medication may not only relieve

the depression, it may also improve mental functioning.

Describe Mood and Behaviours

Moods That May Indicate Depression:

• Apathetic or uninterested

• Withdrawn

• Sad

• Tearful

• Anxious

Emotions That May Indicate

Depression:

• Hopeless

• Helpless

• Sad

• Irritable

• Fearful

• Angry

• Suicidal thoughts

Behaviours That May Indicate

Depression:

• Withdrawn

• Emotional reactions that are inappropriate for the situation

• A raised voice

• Verbal outbursts to staff, family members and/or visitors

• Physically aggressive towards staff, family members and/or visitors

14

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 1

STEP 6: Describe Cognitive Function

The prevalence of cognitive loss in residents who

have had a stroke is affected by many factors,

including the resident’s personality and behaviour

patterns prior to the stroke, the degree of actual

and self-perceived loss resulting from the stroke,

the amount of social support, and the severity

and location of the stroke. If the stroke involved

parts of the brain responsible for memory,

learning and awareness, the residents may

lose his or her ability to remember, comprehend

meaning, learn new tasks, make plans and/or

engage in complex mental activities.

Determining Cognitive Losses

Orientation:

• Does the resident know where he or she is?

• Does the resident know what season it is?

• Does the resident know what year, month and day it is?

Attention:

• Does the resident have a reduced ability to attend to an activity (shortened attention span)?

Memory:

• Does the resident remember what he or she had for his or her last meal or snack?

• Can the resident tell you what activities he or she did today?

Comprehension:

• Can the resident follow simple instructions?

• Can the resident engage in a conversation?

• Can the resident understand written information, as in signs, pamphlets?

• Can the resident understand the humour in a joke?

Recognition:

• Does the resident recognize you?

• Does the resident recognize his or her surroundings?

Further cognition assessment can include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

2

or the Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MoCA).

3

15

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 2

IDENTIFY POTENTIAL FOR IMPROVED FUNCTION

After assessing the resident’s level of functioning, identify the resident’s potential for improving his or her functioning and

quality of life. This can be accomplished through careful observation and ongoing communication with the resident during

day-to-day activities. Look for opportunities to full unmet needs, enhance function and develop potential care goals.

Setting Potential Care Goals

A resident may have already achieved his or her maximum potential in some or all of the following areas of function. If this

is the case, the goal is to maintain current functioning.

Potential

for Improved

Function

Identify Opportunities for Improvement Potential Care Goals

Communicating • Appears frustrated in expressing self • Enhance expressive communication

• Has difculty nding words • Enhance non-verbal communication

to express self

• Has difculty understanding others

• Has difculty understanding humour and sarcasm

• Enhance comprehension

• Has difculty producing a voice

• Imprecise, unclear speech

• Enhance clarity of speech and/or

voice

• Consider input from caregiver(s) regarding

communication habits and/or strategies

16

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 2

Potential

for Improved

Function

Identify Opportunities for Improvement Potential Care Goals

Remembering,

making decisions

and following

instructions

• Requires frequent reminders

• Needs information to be repeated

• Frequently asks questions about where he or she is

• Enhance ability to understand the

information the resident desires

through cueing and other reminders

• Appears frustrated following task instructions • Reduce frustration and/or anxiety

related to poor memory

• Has difculty solving day-to-day problems • Enhance ability to use simple

strategies to solve day-to-day

problems

• Has difculty attending to a task – poor attention,

concentration, impulsive

• Improve ability to attend to a task

• Has difculty with planning and/or sequencing

activities for a particular function

• Enhance ability to perform desired

activities by helping with planning

and/or sequencing

Moving safely

and performing

desired tasks

• Able to partially perform an activity • Increase participation in activities

• Enhance satisfaction with task

performance

• Becomes frustrated trying to do an activity • Reduce frustration

• Weakness limits performance of an activity • Increase strength for activity

tolerance

• Impaired ne motor control • Improve ne motor control

• Has difculty with mobility/transfers • Enhance mobility using equipment,

if needed

• Enhance ability to move safely

• Decreased ability to judge a situation and recognize

the actions that are required

• Enhance judgement

• Has difculty with balance and/or posture

17

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Potential

for Improved

Function

Identify Opportunities for Improvement Potential Care Goals

Perceiving

one’s self and

surroundings

• Loss of awareness in the affected side (neglect)

• Decreased ability to feel part of his or her body

• Enhance recognition of self

• Unaware of his or her limitations • Enhance recognition of abilities

• Unable to see part or all of surroundings • Enhance appreciation of

surroundings

• Limited ability to hear • Optimize ability to hear

• Decreased recognition of people, objects and/or

the environment

• Has difculty appreciating the location of objects

around him or her

• Enhance awareness of

surroundings

• Decreased awareness of time • Enhance awareness of time

Feeling content • Appears withdrawn or socially isolated • Enhance mood

• Cries or laughs at the wrong time and cannot stop

(emotional ability)

• Changes in personality

• Enhance social engagement

• Increase contentment with daily

care activities

• Appears frustrated or anxious

• Expresses frustration and/or anxiety during daily

care activities

• Reduce frustration

• Appears angry • Decrease anger

• Displays aggressive behaviours (verbal and/or

physical)

• Reduce aggressive behaviour

• Lethargic (lack of interest) • Enhance energy level

Participating in

activities he or

she enjoys

• Doesn’t participate in desired leisure activities

• Short attention span

• Enhance participation in the

activities the resident enjoys

• Physical or cognitive limitations to participating in

activities

• Enhance ability/strength/endurance

required to participate in desired

activities.

18

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 3

LISTEN TO THE VOICE OF THE RESIDENT

A basic human need is to communicate our needs, emotions and thoughts. Everything we do involves sending messages

to others.

Communication decits are among the most frightening and frustrating results of a stroke for both the resident and the

caregiver. If a stroke damages the language centre in the brain, there will be language difculties. Some stroke residents are

unable to understand or speak at all. Others seem to know what to say, but the words that come out don’t make sense.

Some can no longer read or write. Many have difculty pronouncing words.

Speech, however, is only one way to communicate. We also communicate non-verbally through how we stand or move,

our facial expressions, as well as the tone of our voice. As we get to know another person, we learn to read each other’s

facial expressions and body language, and communication becomes easier and more successful.

Every conversation has at least two communication partners. Each partner has the responsibility to speak (to send a message)

and listen (to receive and understand the message the other has sent).

Strategies to Help Resident Communicate Successfully

Be aware that in addition to communication changes resulting from a stroke, many residents have decreased hearing and/

or vision. You will need to make adjustments to accommodate these challenges.

Create an Optimal Environment:

• Communicate in a quiet place – turn off the TV or radio, limit other distractions.

• Communicate face-to-face and at eye level.

• Ensure adequate lighting.

• Treat the resident with respect.

Enhance Communication:

• Don’t rush.

• Speak slowly and clearly, in a natural voice.

• Listen carefully and actively.

Monitor the Effect of Your Communication;

• Watch the resident’s facial expressions.

• Be aware of your non-verbal communication – facial expressions, tone of voice.

19

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

19

Do... Don’t...

Communication Do’s and Don’ts

9 Respect the person and his or her message.

9 Be supportive and offer encouragement.

9 Try to discern what the resident is really trying

to say.

9 Offer positive feedback by telling the resident that

he or she is managing well.

9 Gently offer information and assistance to the

resident to enable him or her to become more

independent.

9 Respond to the tone of the message if you are

unable to understand the words.

8 Dismiss the resident’s concerns.

8 Finish the resident’s sentences without rst

asking for his or her permission.

8 Ignore the emotion behind the message.

8 Give false assurances.

8 Offer unwanted advice or make assumptions.

8 Be judgmental.

Empathy and respect are essential to listening and understanding. Empathy is being able to put yourself in someone else’s

shoes and to be compassionate. Empathetic listening is an art that needs to be practised; it will allow you to look beyond

the words to discern what the person is really communicating.

One way to show the resident you are actively listening is to match his or her mood or affect. If the resident is happy and

cheerful, smile and be pleased for him or her. If the resident is sad or distressed, show concern and have a sympathetic

expression on your face.

How the Past Informs the Present

Understanding the resident’s past can help you to identify coping strategies and opportunities for improved life experiences.

Inquire About Resident’s Past:

• Family history, signicant relationships and involvement

• Military service and signicant past events

• Occupation

• Hobbies and interests, leisure activities

• Social history – desired engagement with others

• Specic care preferences

Social history

20

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 3

Inquire About Resident’s Current Realities:

• His or her life in the Veterans Centre

• His or her communication, cognitive and physical abilities

• Perception of family members

• Perception of staff

• Perception of the environment

• Desired activities

Questions to Guide a Discussion of Desired Life Experience

Establish the resident’s desired life experience in the Veterans Centre by asking:

• What is life like for you at the present time?

• Can you tell me about your concerns?

• What is most important to you?

• What information would you like?

• Given your current abilities and what your care team feels you are able to achieve, what activities would you like to be

able to do?

Communicating Your Assessment To Others

Share your cognitive, communicative and behavioural assessments with the resident’s substitute decision maker (SDM). If

the resident is capable, permission is required to share assessment information with the SDM.

Sharing the health care team’s assessment of the resident’s symptoms validates the team’s ndings and assists the resident

and/or SDM to understand the symptoms and the identied needs. This validation and understanding allows the resident

and/or SDM to fully participate in the development of an optimal care plan.

Many family members have a limited understanding of the physical and cognitive effects of a stroke. They may not know how

the stroke has affected the resident’s behaviour and his or her functional abilities. When sharing information, be sensitive to

the fact that in many families, lives are complex. People may be struggling with their own health problems, trying to balance

work and family responsibilities, as well as grieving the loss of their loved one’s abilities.

Effective communication among team members is essential when caring for a resident who has suffered a stroke. It is

important to have ongoing scheduled meetings, including rounds and family conferences, to discuss the resident’s progress

and develop a team approach to a care plan for treatment. Other ways of ensuring good communication include clear

consistent documentation, shift-to-shift reports, and staying up to date with the resident’s progress and care plans.

Staff members must respect the other team members’ values, opinions and expectations regarding treatment; individuals

often have different perceptions of and ideas for treatment approaches.

Resident’s perception

21

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

CARE PLANNING TO ACHIEVE RESIDENT’S DESIRED LIFE EXPERIENCE

Care planning and interventions for a resident who has had a stroke must be individualized. To guide care planning, use a

restorative care philosophy together with a goal-setting framework focused on achieving what the resident considers to be

his or her desired life experience.

Determining appropriate care strategies requires the inter-professional team to carefully assess the resident’s potential

for improvement (see Component 2). Rehabilitative care is most commonly associated with individual disciplines (e.g.,

occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, recreational therapy, neuropsychology), assessing

and treating an individual to achieve optimal functioning. The ABLE approach requires team members to work together to

assess the resident and recommend a restorative plan that specically addresses the resident’s individual needs to achieve

his or her desired life experiences.

Before initiating an intervention strategy, consider that each resident has unique cultural and cognitive perspectives that can

affect his or her motivation to participate. Before starting any treatment, speak with the resident and explain what is about

to happen. Move slowly and explain gently how the intervention will benet him or her. Encourage the resident to participate

as much as possible on his or her own volition.

COMPONENT 4

22

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

Encouraging Communication

After a stroke, some people have specic communication impairments that result from injury to specic areas of the brain.

It is important to know the kind and extent of communication problems to develop appropriate strategies. Improving a

resident’s ability to express and understand will reduce frustration and enhance his or her quality of life.

Communicating with Residents with Aphasia

Goal Approach

Reduce the

person’s

frustration with

communication

• Give the resident your undivided attention

• Provide adequate time for the resident to speak and respond to questions

• Ensure you have facilitative materials to aid in the interaction (pen and paper, alphabet board,

communication board/book, hearing aids)

• Conrm that you have understood the resident by summarizing what they have said, and

verifying their responses to questions (by asking the same question in a different way)

• If the resident appears frustrated and unable to access a specic word, ask them if you can

try and supply it

• If the actual message is not understood, respond to the emotional content

• Reassure the resident that you understand that they know what they want to say, and that it is

the language difculty that is causing problems.

Enhancing

the person’s

understanding

• Ensure a quiet environment

• Face the resident when speaking; ensure you have their attention before speaking

• Speak slowly and clearly, in your natural voice

• Give information in short, simple sentences

• Print key words on paper

• Use pictures, gestures, or refer to objects in the room, to increase clarity of your message

• Refer to clocks and calendars when speaking about date and time

• Discuss one topic at a time. Make changes in topic explicit.

Enhancing

the person’s

expression

• Allow time for responses

• Ignore grammatical mistakes and articulation errors; the goal is to communicate a message,

not perfect speech

• If the resident is stuck on a specic word, either ask them if they can provide a different word,

provide a description instead, or ask if you can try and supply it

• If the resident is not able to verbally express themselves, encourage them to try using gesture,

point to an object, draw, write, or use an alphabet or communication board/book

23

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Goal Approach

Enhancing

the person’s

speech

intelligibility

• Encourage the resident to speak slowly and clearly as able

• If part of a message is not understood, ask the resident to repeat only the part of the

message that was missed

• Repeat the message back to the resident to conrm that you have understood

Communicating with Residents with Cognitive Impairment

• Frequently introduce yourself to the

resident using your name and role.

• Smile and make eye contact.

• Always remain pleasant and calm.

• Listen carefully.

• Watch the resident’s facial expressions

and body language to understand what

he or she is trying to communicate.

• Check with the resident to ensure you

have understood what he or she is

trying to communicate.

Approaches to communicating with

individuals who have cognitive impairment

due to stroke are similar to communicating with residents with dementia. (Refer to Component 3 in Responding to Behaviours

Due to Dementia: ABLE Care Planning Guide.)

Enhancing Movement

Positioning is essential for comfort and to promote optimal functioning. Proper positioning can help a resident function, increase

his or her awareness, and reduce complications such as pain, skin breakdown, contractures and respiratory problems.

24

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

Positioning the Upper Limbs

Goal Approach

Reduce discomfort due to a

dropped shoulder (reduced

muscle tone)

• When the resident is sitting, support the affected arm using a lap tray or arm

trough.

• When moving the resident, always ensure the arm is supported.

• When assisting with walking and transfers, avoid pulling the affected arm.

• When lying in bed, place small pillow under the shoulder / arm

• May need to consider a sling during tranfers/ambulation

Reduce discomfort due to an

elevated shoulder

(increased muscle tone)

• Ensure the arm is aligned.

• Support the arm:

· Use a pillow or folded towel in bed.

· Use a lap tray when seated.

• Assist with appropriate exercises

• Monitor for pain.

• When lying in bed, place small pillow under the shoulder/arm.

25

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Goal Approach

Reduce discomfort and/or

limitations due to a weak hand

with decreased muscle tone

• When the resident is sitting, support the hand using a lap tray or trough.

• To reduce swelling, elevate and support the wrist and hand using a foam

wedge or arm support.

• Place the affected hand in front of the resident with his or her ngers in an open

position. Then, encourage the resident to use his or her other hand to gently

open the affected hand and extend the ngers.

Reduce discomfort and/or

limitations due to a weak hand

with increased muscle tone

(spasticity)

• Position the arm slightly forward from the shoulder.

• Observe for any signs of pain or swelling.

• Elevate the hand on a foam wedge or arm support. Gently open the ngers.

• Encourage the resident to use his or her unaffected hand to gently open the

hand and ngers on the affected side.

• Encourage nger/wrist extension as possible.

26

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

Positioning the Lower Limbs

Goal Approach

Reduce limitations due to a

weak leg

• To decrease stiffness and deformity of the foot, encourage the resident to

stand, if possible.

• When the resident is lying down, elevate his or her feet and/or lower legs. Avoid

pillows under the knees if there is increased tone.

• Try to keep ankles at 90° - may need braces/positioning devices to prevent

plantar exion contractures (Requires OT/PT consult).

• Encourage leg extension

Ensure an appropriate sitting

position to reduce discomfort

and enhance function

• Ensure that the feet are supported and the ankles are at 90° angles.

• Ensure that the hips and knees are at 90° angles.

• Be sure the resident sits with his or her hips at the back of the chair.

• Ensure that the resident’s chair or wheelchair supports proper positioning.

• Make certain that the resident is comfortable.

• Reposition and assess skin every two hours – look for redness, possible

pressure areas.

• If resident is sitting on a chair cushion, ensure it is properly inated.

27

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Promoting a Sense of Surroundings

Goal Approach

Enhance

awareness of

time

• Explain when things will happen in relation to known events – e.g., The music will begin after

dinner.

• Each day, explain the daily schedule and provide reminders.

• To limit confusion, keep the schedule consistent.

• If the resident appears anxious about being late for or missing an appointment or meeting, be

reassuring.

• Gently reinforce the passage of real time – e.g., Your daughter left an hour ago.

• Use a digital or talking clock.

Enhance

awareness

of physical

environment

• Ensure the environment is safe and free of clutter.

• Arrange the environment so there is some stimulation on the side affected by the stroke.

• Place objects of interest on the resident’s affected side to increase awareness of the space.

• To avoid startling the resident, approach from the unaffected side.

• Use visual cues to assist the resident – e.g., place a line of red tape at the edge of a table on

the affected side.

• Encourage the resident to scan the environment. With the Lighthouse Strategy

4

, you ask

the resident to imagine his or her eyes as beams of light sweeping from side to side.

Reduce neglect

of affected side

of body

• Use the affected arm or leg in daily care, if the resident can tolerate it.

• Position the affected arm so the resident can see it.

• Gently rub the affected arm to stimulate sensation and awareness.

• Encourage the resident to help position the affected arm and/or leg for function and visibility.

• Use cues to draw attention to the affected side.

Enhancing Mood and Behaviour

A stroke can decrease a resident’s ability to control his or her emotions. It can also change the way the resident behaves

and interacts with others.

28

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

Approaches to Mood and Behaviour Modications

Goal Approach in Responding

Express

emotions

• Ask the resident how he or she is feeling.

• If the resident loses control of his or her emotions, gently reassure the resident that controlling

emotions can be difcult after a stroke. Consider distracting the resident with an activity he or

she enjoys.

Enhance social

engagement

• Help the resident to engage in his or her favourite activities.

• Speak with the resident when in his or her room.

• Encourage the resident to attend activities that relate to his or her interests and are within his

or her abilities.

• Give the resident opportunities to verbalize life experiences and share his or her memories.

• Support the resident in contacting and participating in spiritual and/or cultural events.

Maximize

function

and reduce

frustration

• Learn the resident’s preferences for daily routines. Follow his or her preferences whenever

possible. Explain when routines need to be broken.

• Explain what you are planning to do so the resident is prepared.

• Help the resident be successful with tasks by alternating between easy and difcult tasks.

• Observe for signs of frustration and offer support or assistance.

• Give resident adequate rest breaks.

• If a situation or activity causes signicant frustration and/or anger, offer to help the resident to

go to another location. Then, redirect the resident’s attention to something he or she enjoys.

Enhance

interest in

activities

• Make it as easy as possible for the resident to participate in activities.

• Reinforce and support any interest the resident shows.

• Use praise to encourage the resident.

• If the resident is initially unsuccessful at a task or activity, gently encourage him or her to try

again.

• If the resident declines participating in an activity he or she will likely enjoy, try asking him or

her to participate again later.

Enhance

judgment

• Avoid situations that require the resident to make decisions beyond his or her capabilities.

• Inform the resident of inappropriate or unsafe behaviours in a simple, direct way.

• Offer appropriate alternatives.

• Avoid criticizing the resident.

• Use praise to reinforce appropriate behaviour.

29

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Improving Memory and Cognition

After someone has had a stroke, his or her memory and other aspects of cognitive function may be affected. Over time and

with appropriate interventions, a resident can improve some of these skills. Use individualized strategies to reduce frustration

and help the resident perform activities of daily living as independently as possible.

Strategies to Improve Memory and Cognition

Goal

Strategies

Improve attention • Reduce distractions – TV, radio, other conversations.

• Give short, simple, step-by-step instructions.

• Ensure the resident understands the instructions you have given before you continue.

• Face the resident and make eye contact to help the resident focus on what you are

saying.

• Give the resident enough time to think and respond.

• Speak and move slowly so the resident doesn’t feel pressured to respond before he or

she is able.

Enhance orientation • Give gentle reminders about time and place – e.g., What a nice spring day!

• Post a calendar to help the resident keep track of the month and day.

• Use a bulletin board to post personal information and family pictures.

• To avoid confusion, try to keep the resident’s schedule consistent and limit changes.

Enhance memory • Encourage memory aids – e.g., calendar, white board, daily planner if the resident is able

to read, recorded voice reminder if the resident is unable to read.

• Patiently repeat information to help the resident remember it.

• Provide simple, clear information that focuses on the information the resident needs.

• Store items in the same places.

• Ensure drawers and cupboards are clearly labelled with their contents.

Enhance insight • Gently remind the resident about his or her limitations, as required.

• Discuss concerns about the resident’s safety with the resident and care team.

• Develop strategies to optimize safety and functioning with the care team.

• Avoid situations in which the resident needs to make decisions beyond his or her abilities.

• If the resident uses a cane or walker, keep it within reach.

• Use signs to remind the resident about safety.

30

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

Goal

Strategies

Enhance ability to

sequence actions

to complete a task

• Encourage the resident to slow down and plan his or her actions.

• Help the resident think about and plan a task.

• Give clear, specic instructions.

• Divide a task into small steps to help the resident focus on one step at a time.

• Give the resident time to practise the task.

• Follow the same sequence each time the task is repeated.

Enhance ability to

solve problems

• Encourage the resident to think about different ways to solve a problem.

• Listen to the resident’s ideas for solving a problem.

• Discuss the benets and risks of possible approaches with the resident.

Encouraging Participation in Activities of Daily Living

After a stroke, a resident may feel previous activities of daily living and/or leisure pursuits are now too difcult. To engage in

desired activities, the resident may need attention to the environment and encouragement with appropriate cueing, assistive

devices and the proper pacing of activities.

General Guidelines:

• Ensure hearing aids and/or glasses are used appropriately.

• Ensure the resident can hear and/or see you.

• Identify how the resident would like to participate in his or her activities of daily living. Ask about:

· timing

· order of care

· how assistance is best provided.

• Assess and manage pain or discomfort.

• Recognize fatigue and respond with a exible approach.

• Remain optimistic.

• Expect uctuations in cognitive and physical abilities from day to day.

Create an Optimal Environment:

• Ensure an appropriate room temperature and privacy.

• Reduce distractions – noise from TV, radio, room, hallway.

• Minimize barriers to movement.

• Ensure adequate lighting.

• Ensure that appropriate equipment and/or assistive devices are available and within reach.

31

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Reminding Through Cueing

Visual Cueing Verbal Cueing

Tactile Cueing

• Position the resident’s impaired limb within

his or her view.

• Help the resident turn his or her head to the

affected side to see objects.

• Move objects to the resident’s visual eld on

the affected side.

• Consider moving the bed so the main action

of the room is on the resident’s affected

side.

• Remind the resident of the

stroke-affected side of his or

her body.

• Encourage the resident to

touch and view the affected

side.

• Touch the affected limb with

various textures.

• Encourage and help the

resident to participate in

activities that require the use

of both hands. (This is an

effective way to develop an

awareness of an affected

limb.)

Caregiving Strategies:

• Encourage adequate rest periods.

• Provide care when the resident is motivated and agreeable to participating.

• Always monitor for pain and discomfort during care.

32

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 4

• Offer choices about order and pace of care.

• Use visual, verbal and tactile cues.

• Enable the resident to perform activities and/or tasks he or she can

perform.

• Ensure clothing design, t and fasteners are appropriate for the

resident.

• Dress the affected side rst.

• Undress from the non-affected side rst.

• Encourage family members and other visitors to verbally reinforce the

resident’s efforts to participate in his or her daily care.

Enhancing Dressing and Grooming

What To Use What To Avoid

9 A mirror

9 Clothes that fasten at the front

9 Velcro fasteners

9 A long-handled shoe horn

8 Tight-tting sleeves, armholes, pant legs and waistlines

8 Clothes that need to be put on over the head.

8 Small buttons, ne zippers and other fasteners that require dexterity

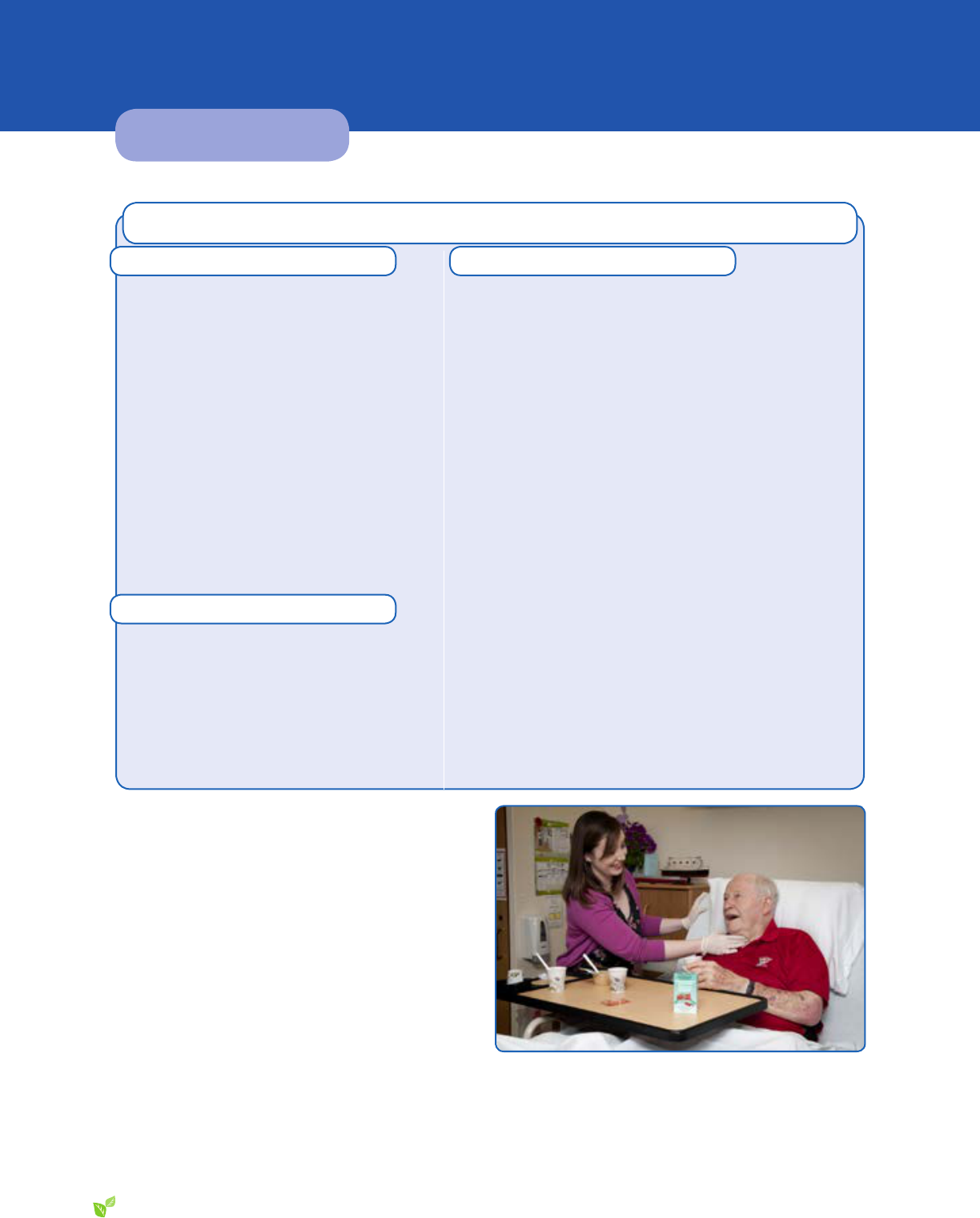

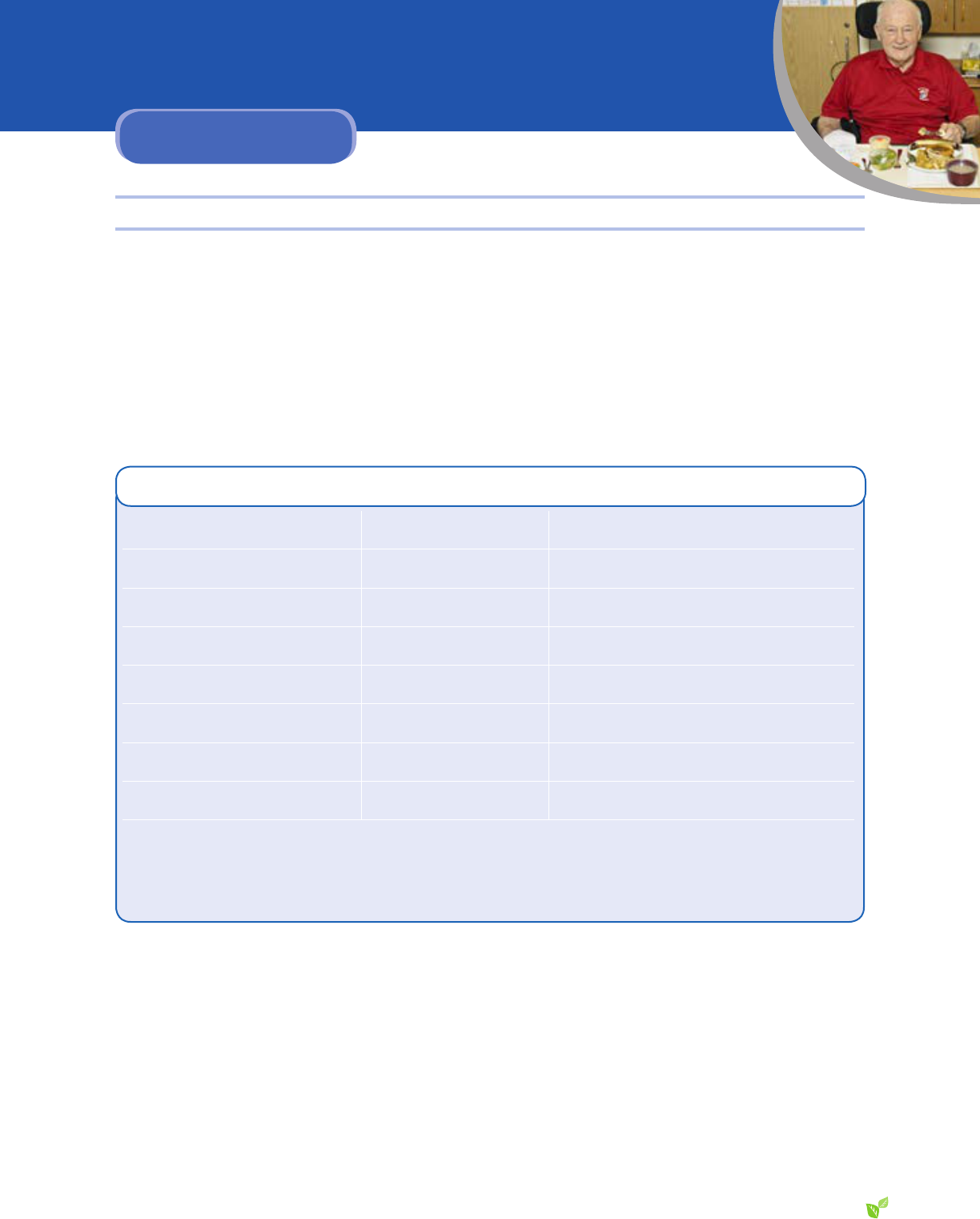

Dining

Create a pleasurable dining experience by paying attention to the resident’s abilities and his or her preferences.

• Ensure the level of auditory, social and visual stimulation is appropriate for the resident. To decrease distractions,

consider providing one food item at a time.

• Conrm that food choices are consistent with the resident’s preferences and recommended diet.

• Ensure the food texture is appropriate for resident’s ability to chew and swallow. (A dentist and/or speech-language

pathologist can provide this assessment.)

• Consider more frequent smaller meals if the resident appears to become tired before nishing a meal.

• Use assistive feeding devices to allow for independence.

Consider:

· Plates with rims

· Plate guards

· Non-slip placemats

· Modied cups

· Large handled spoons

· One-handed rocker knives

33

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

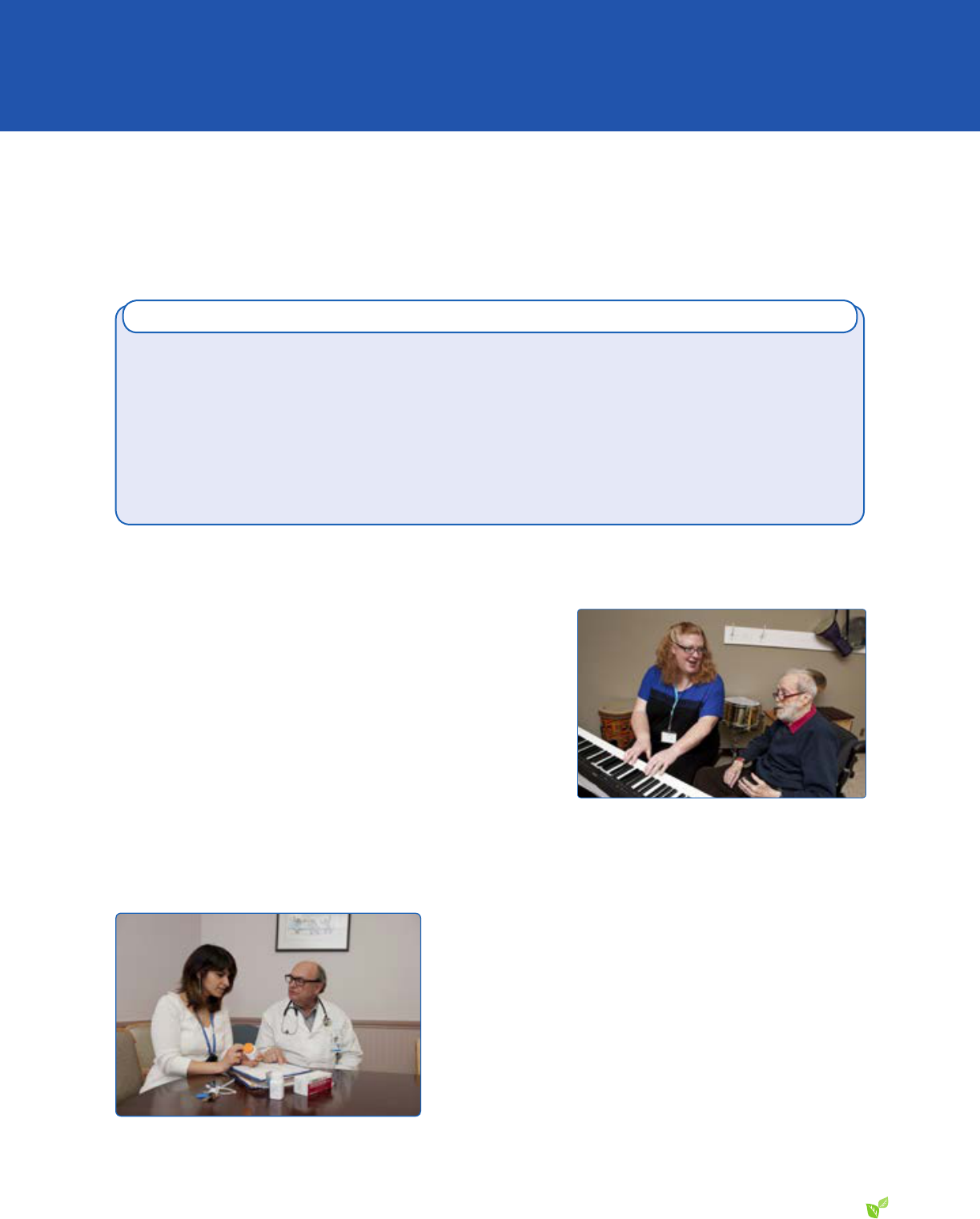

Recreation and Leisure Activities

To enhance the resident’s participation in leisure activities, discover ways

to engage him or her in recreational, and religious or spiritual activities. By

participating in social gatherings, exercise and/or music groups, creative

arts and pet visits, the resident can enhance his or her quality of life.

Ensure adequate rest prior to the activity. Then, make sure the resident

is dressed and positioned appropriately for the activity. Before, during

and after the activity, monitor for pain.

Enhancing Participation in Leisure Activities

What to Use What to Avoid

Games

9 A card holder

9 Large playing cards

9 A battery-operated shufer

9 Puzzles with large pieces

Games

8 Small cards

8 Games beyond the resident’s cognitive skill set

Reading

9 A book holder

9 Books on tape

9 Large-print crosswords

9 Magazines

Reading

8 Books with small print

8 Paperback books that are to small to t into a book holder

8 Newspapers

Computer

9 A large monitor

9 A large font size

9 A modied keyboard

Computer

8 Frustration from an inability to use the computer or see

the screen

Crafts

9 A needle threader

9 A one-handed embroidery hoop

9 A one-handed knitting and crochet clamp

9 A C-clamp to stabilize projects

9 Enlarged grips for pens, pencils, paintbrushes

Crafts

8 Activities requiring ne nger movements beyond the

resident’s abilities

8 Crafts with complex instructions or sequencing

8 Activities requiring a co-ordination of movements beyond

the resident’s abilities

34

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE ADVERSE OUTCOMES

After a stroke, a resident is at risk for a number of health issues. With careful attention and monitoring, you can identify these

risks early and plan interventions to prevent a decline in health and function.

Ensuring Adequate Hydration and Nutrition

After a stroke, a resident may not eat and drink enough to maintain his or her hydration and nutritional needs. This can be

due to a reduced appetite, difculty swallowing, a reduced ability to feed him or herself and decreased cognition.

Ways to Enhance Oral Intake:

• Ensure the resident’s diet includes his or her preferred foods.

• Offer food and uids more frequently than the scheduled times.

• Provide rest periods, as needed.

• Set up the resident’s meal so he or she can see it and be as independent as possible.

• Offer assistance if a resident is having difculty self-feeding.

COMPONENT 5

35

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Hydration

Dehydration occurs when a resident’s uid intake is less than the uid required to meet the body’s needs. There may be

a sudden decrease in uid intake or a gradual decline over days to weeks. Careful monitoring of uid intake can detect

insufcient uid consumption prior to adverse outcomes.

Consider Dehydration if There Is:

• Decreased urinary output

• Dark or strong-smelling urine

• Frequent urinary infections

• Thick saliva

• Constipation

• Dry mouth (causing difcult speaking)

• Dizziness when changing positions

• Increased confusion

• Weight loss

• Decreased skin turgor

• Sunken eyes

For strategies to encourage uid intake, see Appendix 3.

Nutrition

Malnutrition occurs when a resident’s food intake does not meet his or her calorie, protein and other nutrient requirements.

To identify a resident at risk of malnutrition, monitor his or her food intake on a daily and weekly basis, and weigh the resident

every month (or more frequently, if needed)

Consider Malnutrition if There Is:

• Weight loss

• Fatigue and reduced motivation

• Impaired wound healing

• Skin breakdown

• An increased number of infections

Swallowing

A stroke may cause muscle weakness, paralysis and decreased co-ordination in the mouth and throat. This can lead to

slow and/or ineffectual swallowing (dysphagia) and an increased risk of aspiration.

36

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 5

Warning Signs Associated with Dysphagia and Aspiration Risk

5

General Observations:

• Decreased level of alertness

• New delirium or heavy sedation

• Facial weakness or drooping

• Drooling

• Dysarthria

• Weak or absent voice

• Weak or absent cough

• Unexplained weight loss

• Inability to handle oral secretions

• Medical history of recurrent chest infection/

pneumonia

Changes in approach to food:

• Avoidance of eating

• Spitting food out

• Special preparation of food or avoidance

of specic items

• Prolonged meal time, intermittent cessation

of intake

Observations or complaints of:

• Excessive, lengthy chewing

• Holding food in the mouth

• Pocketing or pooling of food and drink in the mouth

(in the cheek, on the tongue, or on the roof of the mouth)

• Delay or absence of the swallow (elevation of the Adam’s

apple or thyroid cartilage)

• Multiple swallows used with each sip/bite

• Wet, or hoarse voice

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing

• Frequent throat-clearing

• Regurgitation

• Sensation of obstruction in throat or chest

• Use of compensatory measures (using drinks to “wash

down” each bite, excessive head movements while

swallowing)

Aspiration refers to the inhalation of food or liquid into the

airway. It can cause an airway obstruction (choking), upper

respiratory infections or pneumonia. Individuals may cough

or silently aspirate their food and/or beverage. If there are

concerns about risk for aspiration, consult a physician and/

or speech-language pathologist. To remember ways to

promote safe eating and feeding, you may nd it useful to

use the mnemonic “pâté.”

37

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Positioning

• Sit upright (90 degree angle if possible).

• Position and maintain the head with the chin tilted slightly down towards their chest. use pillows, blanket rolls, or

head rests behind the head (not the neck) to position the head and maintain the chin tilted downward. It is critical

to maintain the chin tilt position throughout the meal to prevent foods or uids from falling into the throat.

• To maintain downward chin positioning and prevent tilting the head back, remember to:

1. Be at eye level with the person, do not stand over them

2. Use wide rim cups or “nosey“ cups for drinks

3. Position the person so that they can see you and the food

• To prevent reux, avoid lying down for 2 hours after a meal (if the resident is in bed, elevate the head of the bed

to 45 degree angle)

Amount

• Encourage 1 (teaspoon - tablespoon) of food or 1 small sip uid per swallow. Watch the neck for the swallow action

before giving more. Postpone feeding if swallow action is not present.

• Give rest breaks when feeding

Textures

• Check that the person is receiving the recommended food texture and uid texture (see Appendix 3)

• Avoid mixing foods together

• Avoid washing down solids with thin liquids

Enablements

• Check the Care Plan for specic feeding recommendations.

• Ensure that glasses, hearing aids and feeding aids are used if required.

• Check the temperature of the food / uid before feeding

• Acknowledge the resident’s likes / dislikes / preferences / abilities.

*© Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Chris Watson SLP) 2001

SAFE UNSAFE

P.A.T.E.* - Safe Eating and Feeding Guidelines

38

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 5

Preventing Contractures

A contracture is a permanent shortening of a muscle. The result is deformity of a joint with or without pain. It can be

caused by increased tone in a muscle after a stroke, improper positioning or decreased movement of a joint. Prevention

of contractures is important in maintaining abilities and achieving comfortable and functional positioning. Follow these tips:

• Encourage the resident to actively move his or her muscles and joints through daily routines identied by the inter-

professional team.

• Provide activities that encourage the resident to move his or her muscles and joints.

• If the resident has muscle weakness, carry out assisted but gentle range-of-motion exercises during bathing, dressing

and/or other daily activities. If the resident resists, ask for an assessment from an occupational or physical therapist.

• Use splints and/or braces to help prevent contractures, if needed. They can ensure optimal positioning during sleep.

(refer to OT/PT)

• Support the affected limb(s) when the resident is in bed or a wheelchair. When possible, the resident’s arms and legs

should be placed in their longest positions.

• Ensure the knees are as straight as possible when in bed.

• Encourage frequent changes of position.

Do’s and Don’ts for Preventing Contractures

Do Don’t

• Place small towels, rolls or pillows under the scapula

and pelvis.

• Try to keep the affected arm/leg straight as extended

as possible.

• Place small towels or rolls under the pelvis.

• Ensure the body is aligned in a neutral position.

• Encourage resident to actively move/stretch his/her

limbs as often as possible.

• Let the wrist or ngers stay in a exed position.

• Put pillows under the knees.

• Let the resident lean or bend to one side when lying in

bed.

• Allow the resident to lean or bend to one side when

sitting.

39

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Recognizing and Responding to Pain

After a stroke, many residents experience pain. Pain can be a direct result of the stroke (e.g., central post-stroke pain) or

from a disability resulting from the stroke (e.g., shoulder-hand syndrome). In addition, a resident may have pain or discomfort

from other conditions, such as arthritis, previous injuries and/or poor circulation.

The rst step in minimizing pain is to recognize that the resident is having pain. Since the resident may not be able to

communicate that he or she has pain, be alert for signs of discomfort.

Cues to Consider Pain

Verbal and Oral Cues:

• Words such as “itching,” “burning,” “throbbing”

• Moaning or groaning

• Crying or sighing

• Gasping

• Yelling or swearing

Non-Verbal Behaviours:

• Rubbing or massaging a part of the body

• Bracing, holding or guarding a part of the body, especially when moving

• Shifting or rocking (an inability to sit or be still)

• Incontinence due to pain

Facial Expressions:

• Frowning

• Grimacing

• Wincing

• Turning face away

• An angry expression

• A furrowed brow

Behavioural Changes:

• Increased restlessness

• Being quieter than usual

• Decreased appetite

• Decreased interest in usual activities

• Less social interaction

40

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 5

Stroke-Related Pain Syndrome

(6-8)

Type of

Pain

Cause Characteristics Management

1. Central

post-stroke

pain (<10%

of residents)

• Direct result of an

injury to the brain and/

or spinal cord

• Pain can be constant or

intermittent

• Pain can be burning,

tingling or stabbing

• Pain is worse with

activity, a light touch, cold

temperatures or weather

change

• No visible sign of injury or

tissue damage

• Pain often more than

expected from touch and/

or contact

• Ensure optimal positioning

• Minimize touch and/or contact with

objects that increase pain

• Medications:

· Analgesics

· Antidepressants

· Anticonvulsants

• Consider:

· Nerve blocks

· Local anesthetics

2. Shoulder

subluxation

• Stiff, spastic muscles

and/or contractures

• Overstretched or limp

muscles

• Shoulder pain on side

affected by stroke

• Carefully support and position the

shoulder

• Gently move the arm and shoulder,

avoiding aggressive range-of-motion

movements or exercises

• Support the arm and shoulder during

activities of daily living

• Ensure the arm and shoulder are

supported when the resident is

walking, standing or sitting

• Slings, arm boards and lap trays

maybe benecial in some patients

howewer need to be monitored to

prevent over-correction

3. Spasticity

• High muscle tone

resulting from the

stroke shortening

muscles around a joint

• Stiff muscles

• Reduced joint

movements, usually in

the shoulder, elbow, wrist

and/or hand

• Position properly

• Offer gentle range-of-motion exercises.

(Consider a physiotherapy consult.)

• Avoid forcing the limb to move

• Apply custom-made or t splints

as directed by an occupational or

physical therapist

• Consider anti-spasticity medications

and/or a referral to a physiatrist

41

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

Type of

Pain

Cause Characteristics Management

4. Shoulder-

Hand

Syndrome

• Reex dystrophy of

the upper extremity

• Intense, burning pain

• Continuous pain

• Increased pain over time

• Limited movement of

hands and/or ngers

• Diffuse tenderness and

decreased shoulder

movement

• Avoid touch and contact that causes

pain

• Follow the recommended positioning

to protect the affected arm or hand

• Physiotherapy

• Analgesic medications

• Be sympathetic

• Consider a ganglion block if the pain

persists

5. Adhesive

capsulitis

• Tightening of the

capsule of the

shoulder due to

inammation or a lack

of movement

• Stiffness with a decreased

range of motion in the

shoulder

• Pain with range of motion

• Offer gentle mobilization exercises, as

directed by a physiotherapist

• Position properly

• Physiotherapy

6. Bursitis

• Inammation of the

subacromial bursa

• Pain on the outside

of shoulder that with

movement may travel

down the arm

• Physiotherapy

• Position properly

• Offer gentle range-of-motion

exercises

• Consider a subacromial steroid

injection

7. Brachial

plexus

fraction

neuropathy

• Flaccid arm that has

been unsupported

• Pulling on resident’s

arm during transfers

• Loss of sensation or

neglect can increase

the risk of fraction

neuropathy

• Continuous pain

• Pain often has burning

quality

• May have reduced

movement and/or

sensation in the hands

and/or ngers

• Forearm

• Use proper transfer techniques, as

recommended by a physiotherapist

• Position properly

8. Trauma

due to

neglect or

decreased

sensation

• Inadvertent injury to

arm, hand, leg or foot

• Failure to appreciate

environment because

of decreased

sensation in the

affected side

• Variable, depending on

the location and type of

injury

• Treat the injury

• Educate the resident, family members

and staff about protecting the

affected limb during activities and/or

movement

9. Rotator

cuff

tendonitis

and/or tear

• Inammation of the

rotator cuff tendons

of the shoulder due to

overuse or injury

• Tears can result from

movement beyond

• Pain only with certain

shoulder movements

• Less pain when shoulder

moved passively

• Physiotherapy

• Range-of-motion exercises

• Corticosteroid injections, if

appropriate

42

continued

© 2012, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Veterans Centre. All rights reserved.

Restoring Abilities After a Stroke using Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE) Care Planning Guide

COMPONENT 5

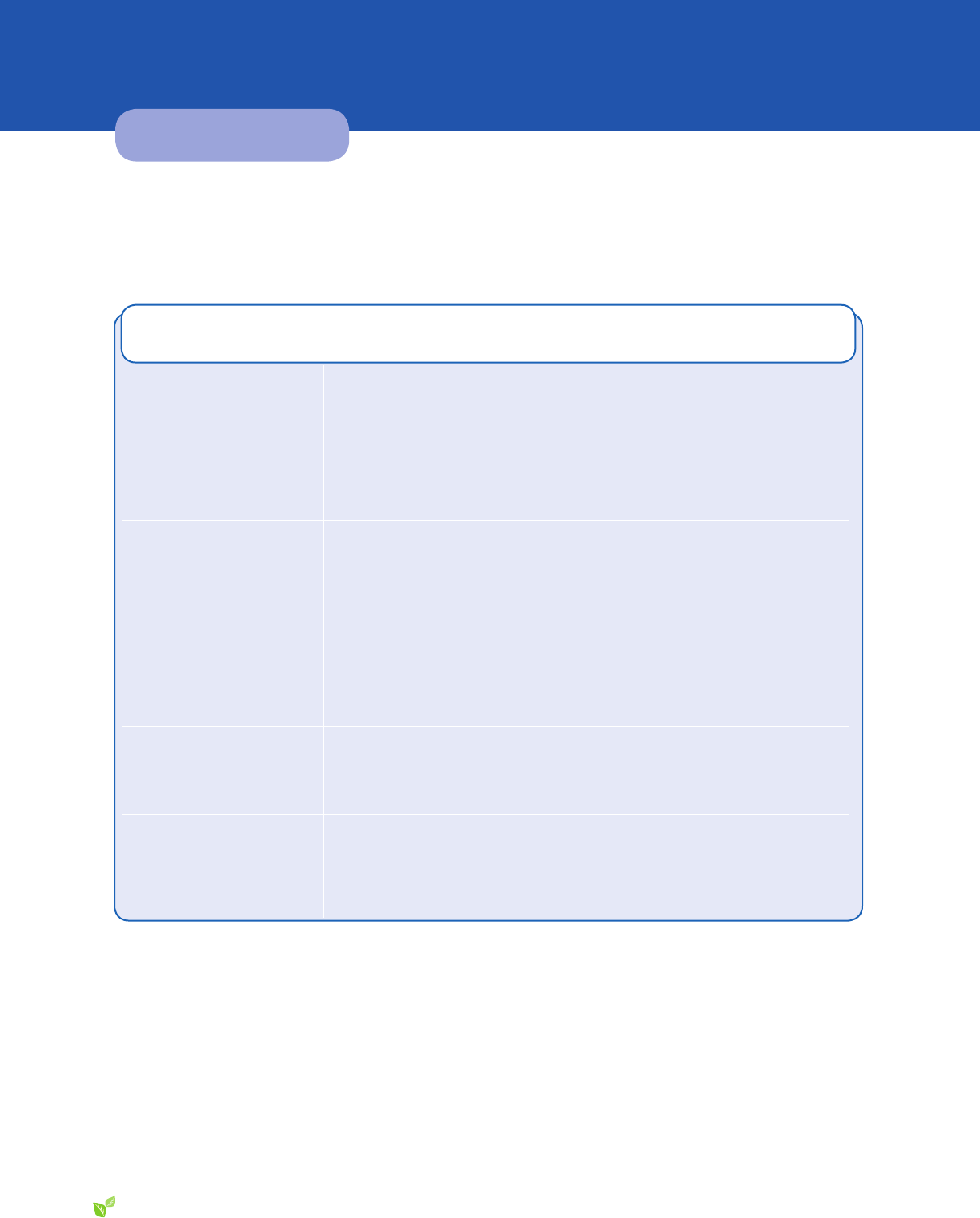

Promoting Continence

Bladder control

Stroke can affect a person’s ability to recognize the need to urinate and respond in a timely manner. It can also affect the

intensity and frequency of bladder contractions, and the ability of the urethral sphincter (valve) to contract and relax.

Mechanism Affected

by the Stroke

Result Strategy

Increased bladder

contractions

9,10

• Urge incontinence

• Frequency

• Urgency

• Incontinence

• Nocturia

• Schedule voiding with gradually longer

intervals between voiding

• To decrease urges, use distraction and

relaxation strategies

11

Decreased bladder

contractions/coordination

with sphincter

10

• Overow incontinence

• Prolonged bladder emptying and/or

failure to empty)

• Over-distended bladder

• Retention of urine

• Ask the resident to attempt to void

twice (double voiding) each time

• Recognize decreased output

• Consider a post-void bladder scan

to identify physiological issues.