Self-Care Social Prescribing

Kensington & Chelsea Social Council and

NHS West London Clinical Commissioning Group

January 2018

Social Return on Investment

This report was prepared by Envoy Partnership,

an advisor in evidence-based research and

strategic communications. We specialise in

measuring and demonstrating the value of social,

economic and environmental impacts. We are

dedicated to providing organisations, stakeholders,

investors and policy makers with the most holistic

and robust evaluation tools with which to enhance

their decision-making, performance management

and operating practices.

‘ All good GPs understand that healthcare and wellbeing

is made up of physical, psychological and social

problems. Providing holistic care involves all these

elements...however if somebody’s prime issue is

loneliness [or social isolation], it’s much better

that they’re NOT seeing a GP but getting support

from other parts of the community and other parts of

the system.

In the [consultation] room, all the time I’m

suggesting to [older] patients: charities, local

health groups, support groups; things they can join

and make them feel valued, worthwhile, and important

members of society.

I wasn’t trained to give social care advice, I was trained

to do medicine, but we care about our patients and want

to give holistic all-round care’

Dame Helen Stokes-Lampard

Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners

12 October 2017, BBC News

1Social Return on Investment

Acknowledgements

Executive summary

Background

Services available through social prescribing

Impact evaluation objectives and method

Findings: Patients

Findings: Valuing the utility of patient health

and wellbeing outcomes

Findings: Health and Care system

Findings: Working with VCS providers

Programme fit in the local system

Recommendations

Appendices

Contents

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

2

3

7

10

13

16

24

27

34

37

38

40

Self-Care

Social Prescribing

Kensington & Chelsea Social Council and

NHS West London Clinical Commissioning Group

Social Return on Investment

Self-Care Social Prescribing2

We would like to thank the voluntary and community service providers from the

pilot phase, frontline staff and volunteers who supported our research and helped

to arrange interviews, group observations, and surveys with their service users,

in particular: Action Disability Kensington & Chelsea (ADKC) in conjunction with

Life in Balance, Age UK, Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) Westminster, Chinese

National Healthy Living Centre, Healthier Life 4 You (now Healthier Divas),

Metrosexual Health & Wellbeing Community Interest Company (MHW CIC),

Open Age, Resonate Arts (formerly Westminster Arts), and the Venture

Community Association.

We also wish to the thank the Case Managers, Health and Social Care Assistants,

and Dr Oisin Brannick (lead GP for West London Clinical Commissioning Group

(WLCCG) Social Prescribing) for the valuable information and insight provided for

our research.

We are very grateful to the members of the local Transformation Steering Group for

aiding our understanding of how the social prescribing model fits with local authority

objectives for the health and wellbeing of older people.

Our thanks also go to Dr Susan Procter at Buckinghamshire New University, who

was a valuable sounding board, and facilitated access to acute hospitalisation data.

Our research would not have been possible without the involvement of the

Kensington and Chelsea Social Council team, and input from Kalwant Sahota

and Henry Leak and colleagues at West London Clinical Commissioning Group,

to whom we are extremely grateful for their time and energy.

Finally, our greatest thanks go to the patients and service users. We feel privileged

to have been welcomed into their homes and lives, and for them to have shared

their experiences, feedback, and stories with us, often under very difficult

personal circumstances.

Acknowledgements

3Social Return on Investment

Health and social care services in North and

West London are building positive new models

of cross-sector working to make better use of

joined-up resources. Such cultural and operational

change is needed to improve choices available

for patients, and to support professionals to go

beyond the medical model alone. The status quo

is not sustainable, given our ageing population

and the growing prevalence of long-term life

limiting illnesses.

In West London, a frail older patient can take

up an average of 30 GP practice visits per year,

over 12 days in hospital per spell, and 8 visits to

outpatient clinics annually. Many older patients are

at risk of being increasingly isolated, housebound,

and are suffering from poor social and emotional

wellbeing. This further amplifies the problems with

their existing health conditions and can lead to

more rapid deterioration. However, treating such

non-medical drivers of poor health and wellbeing

are not the conventional domain of doctors, nurses,

and other clinical professionals.

The Self-Care social prescribing model enables

GP practice staff to refer patients with a non-

medical health and wellbeing need onto appropriate

specialist services from the voluntary and

community sector (VCS). Patients are provided

with a personal consultation with a Case Manager

or Heath and Social Care Assistant at their GP

practice, to identify their needs, interests, and

goals. One option available is for the patient to be

prescribed a service on the Self-Care directory.

Patients are contacted by the service provider

within a week to arrange their sessions and work on

their progression. The general aim of Self-Care is

to increase patient confidence in making informed

decisions about their health, and increase lifestyle

changes and new healthy habits, through accessing

more community-based support sessions. The

Self-Care social prescribing model has led to

reduced avoidable need for hospitalisations,

reduced need for GP practice hours, and

reduced levels of physical pain and depression

for patients.

This Self-Care social prescribing model and

directory of services is managed by Kensington

and Chelsea Social Council (KCSC) on behalf

of West London Clinical Commissioning Group

(WLCCG). The model forms part of WLCCG’s

integrated ‘My Care, My Way’ (MCMW)

programme, which places over-65s at the heart of

a personalised and holistic care and support plan.

Envoy Partnership were commissioned to conduct

research to evaluate the impact of this model and

include a Social Return on Investment (SROI)

analysis. This is detailed comprehensively in the

main report, which describes the total SROI value

created when compared with the annual contract

budget of £250,000. The results are as follows:

Executive

summary

£2.80 of social

value created

per

£1 invested

£

Self-Care Social Prescribing4

Executive summary

The Self Care model reached around 800 frail older

patients in the pilot year and is forecasted to reach

around 1300 patients in the year to March 2018.

Patient impacts observed from the research include:

• Reduced physical pain and discomfort

• Reduced depression and severe anxiety

• Reduced levels of loneliness and social isolation

• Improved self-confidence/self-worth

• Improved sense of health equality i.e. feeling

valued the same as other people by care services

• Maintained independence and dignity, especially

when enabled to access income support

• Reduced avoidable need for entering primary

and secondary care

Total attributable worth (or ‘utility’) to patients

of these impacts is valued at £278,400 for the

pilot year to March 2017. Patients receive six

sessions, with an option for re-referral for another

six sessions, sometimes with a different related

service. Through patient surveys (see Table A)

we observed an increase in the proportions of

patients who feel: i) No pain or little pain (+24%),

ii) No feelings of being down or depressed (+17%),

and iii) No feelings of anxiety (+14%).

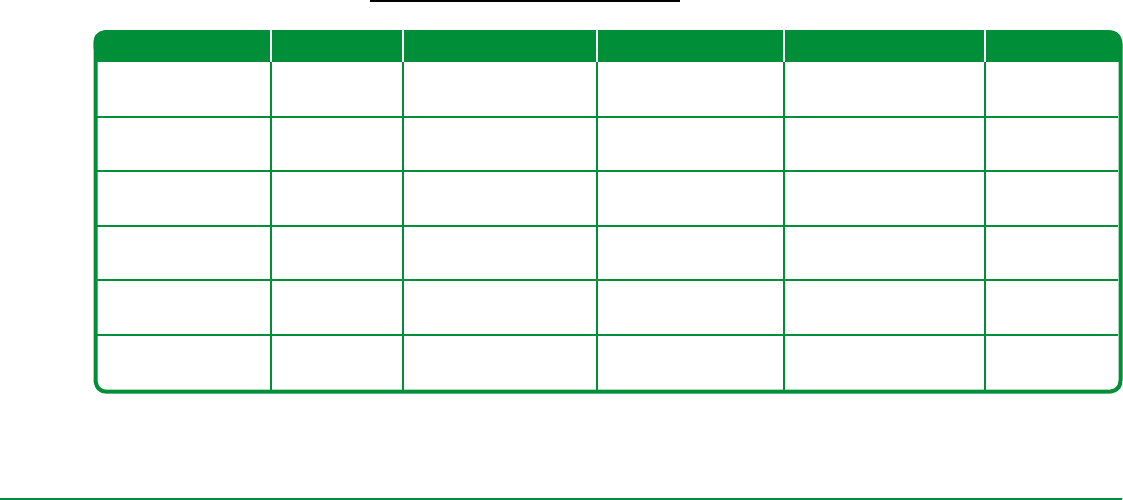

Table A. Patient survey responses regarding

health status outcomes resulting from social

prescribing (based on the short EQ5-d and

PHQ9 surveys, N=134)

Resource value to health services

The social prescribing model has also led to

resource savings to GP practice staff - including

Health and Social Care Assistants (HSCAs) and

Case Managers – valued at £102,000 for the

pilot year (April ‘16-March ‘17) and forecasted at

£150,000 to March 2018. Resource savings for

hospitals are valued at £106,000 for the pilot

year and forecasted at £154,000 to March 2018

(see Table B). This is calculated for acute episodes,

by drawing on improved Patient Activation Measure

(PAM) scores. PAMs are recorded by GP staff with

patients, at different points in time.

YEAR END TO MARCH 2018 –

FORECASTED ‘SROI’

• c.£6.25 for every £1 invested, including

health service value (c.£1.22) and patient

health and well-being value (c.£5.03).

• After accounting for the attribution due to other

factors, the ‘attributable’ SROI is c. £2.80.

% of Patients

responding Before After Change

Little or No pain 15% 39% +24%

No feelings of

being depressed

30% 47% +17%

No feelings of anxiety 29% 43% +14%

PILOT YEAR TO MARCH 2017 – ‘SROI’

• c.£4.30 of value is created for every £1

invested, including health service resource

value (c.£0.85) and patient health and well-

being value (c.£3.45).

• After accounting for the contribution of

other factors that affect patients’ health and

wellbeing outcomes (the attribution), c.£1.90

of attributable value was created for

every £1 invested.

5Social Return on Investment

According to the PAM scoring system

1

used by

WLCCG, an improvement by one-point correlates

to 2% reduced hospitalisation likelihood. Around

62% showed an improvement from our sample.

The average improvement for those 62% was 5.8

points. Therefore, one of the areas of resource

savings indicated by the improvement in patient

activation would be an average 11.6% rate of

reduced hospitalisations, for the relevant proportion

of patients who improved.

Table B presents avoidable demand and resource

value to local health services, at GP practice level

and hospital level, with hospital estimates linked to

the PAM score for the proportion of patients who

showed improvement. Patient utility was valued

separately using a QALY approach.

Table B. Resource value to health services (from 24 GP practices, values rounded to

nearest 1000)

Areas of resource saving

Total

reduction

Pilot year

to Mar 2017

Equivalent

consult’ns

per practice

Pilot year

Total Value

Pilot year

to Mar

2017

Total Value

forecast

YE to Mar

2018

Average

incidence per

patient per

year, MCMW

GP Practice level total £102,000 £150,000

Diverted GP hours: initial

consultations (w/ re-referral)

340 hours 57 £18,000 £27,000

30 GP

practice visits

per patient

Diverted HSCA & CM

research/support hours: initial

consultations (w/ re-referral)

1025 hours 171 £21,000 £31,000

Avoided GP hours from patients

stopping need for consultations

(6-month period)

590 hours 98 £32,000 £46,000

Avoided HSCA & Case

Manager hours from patients

stopping need for consultations

(6-month period)

1480 hours 247 £31,000 £46,000

Hospital level total £106,000 £154,000

Reduced need for Hospital spells

51

incidences

n/a £68,000 £99,000

1.19 episodes

@12 bed days

Reduced need for A & E

54

incidences

n/a £6,000 £9,000 1.23 episodes

Reduced need for

Outpatient visits

579

incidences

n/a £32,000 £46,000 8 episodes

1

Licensed by NHS services from the US company, Insignia Health

c.11.5%

reduced

hospitalisations

1300 patients

reached in 2018

Self-Care Social Prescribing6

Key strengths of the model identified in our

research are that:

• The Self-Care offer enables agile and flexible

commissioning, whilst supporting some frontline

administrative functions.

• GP practices and patients are able to reach more

VCS services appropriate to their needs (and thus

work more effectively with their time).

• Management of the model by an accountable

VCS umbrella organisation. such as KCSC,

generates trust between providers, health

services, patients, and other statutory

stakeholders.

• It can foster cross-sector collaboration to better

join-up resources and access capacity.

• There are significant contributions to patient

wellbeing, motivation/activation, and confidence.

• Resource savings are created for care services,

especially reduced hospitalisations, and GP

time and Case Manager time spent on care co-

ordination, planning, and research.

Recommendations for the model are focused on:

• The need to improve feedback about patient

progression into Care Plans, through better

integration of information between two different

software systems used by WLCCG and KCSC.

• Expanding services to less frail patients therefore

supporting a preventive approach.

• Increasing initial number of sessions, whilst

reducing the need for re-referrals.

• Building the profile of the model and building

confidence more widely amongst professionals.

• Improving compliance and guidance, regarding

Quality standards and Information adequacy.

• Ensuring service providers and health

professionals meet their responsibility to

collectively improve learning and share

best practices.

Executive summary

7Social Return on Investment

Kensington and Chelsea Social Council (KCSC)

is operating a social prescribing model, known

as Self-Care, on behalf of West London Clinical

Commissioning Group (WLCCG). The Self-Care

model links patients in primary care with sources

of health and wellbeing support from specialist

voluntary and community services. The Self-Care

programme is targeted at patients aged 65+ with

long-term conditions. It provides GP practices in

Kensington and Chelsea and the Queens Park

and Paddington areas of Westminster with a

non-medical referral option.

The Self-Care social prescribing model is part of

the ‘Whole-Systems’ initiative, which is a cross-

sector network of commissioning authorities

across health care, social care, and other statutory

support. Self-Care currently operates within the

larger integrated ‘My Care, My Way’ (MCMW)

programme, which places over-65s at the heart of

a personalised and holistic care and support plan.

The aim of the Self-Care approach is to increase

patient confidence in making informed decisions

about their health. Simple lifestyle changes and

new healthy habits and goals are encouraged.

Consequently, Self-Care is expected to positively

contribute to patients’ confidence and motivation,

which in turn is expected to contribute towards a

long-term reduction in use of primary, secondary,

and some tertiary services.

It was originally planned that only patients in Tiers 2

and 3 (as described below) would receive Self-Care

services. This was later expanded to Tier 1 patients.

The Tiers of patients are defined as follows:

The key aspect of Self-Care social prescribing

is that it focuses on provision of services

and activities to patients by Voluntary and

Community Sector (VCS) organisations who

specialise in providing health and wellbeing

services to older residents.

Rationale for developing the

Self-Care model

Self-Care was created to offer a range of broader

benefits for anyone aged 65 or over, including:

1. Background

Tier 0: +65 years of age and are mostly healthy.

Tier 1: +65 years of age and have one well-

managed Long-Term Condition (LTC).

Tier 2: +65 years of age and have two LTCs,

mental health or social care needs.

Tier 3: +65 years of age and have three or

more LTCs, mental health or social

care needs.

Self-Care Social Prescribing8

• More time – patients have longer

appointments with their GP practice (as their

appointments can also be with non-GP staff).

This helps GPs to focus their time on medical

rather than non-medical factors affecting health

and wellbeing.

• More support – access to a broader range of

health and social care professionals to support

health and wellbeing.

• More help – through creating integrated care

centres that can offer a wide range of services

under one roof – including diabetes clinics,

pharmacists and social care services

(such as St Charles Integrated Care Centre).

• More choice – patients are offered local activities

to support them in looking after their own

physical, social, and emotional wellbeing.

(adapted from WLCCG service specification for Self-Care 2015)

Self-Care social prescribing model

The Self-Care referral process is conducted in

three main steps, as part of the My Care, My Way

offer to older patients:

After assessing and agreeing the patient’s needs

and choices, Case Managers or HSCAs refer

the patient via KCSC to one of the Self-Care

services or activities. KCSC receives the referral

and notifies the provider, who in turn contacts

the patient and arranges to deliver the activity or

service. KCSC have no direct contact with any

patients, and act as a bridge between the VCS

providers and practice-based staff who have

responsibility for patient contact. The graphic in

Figure 1 illustrates the pathway of how the six

sessions are prescribed within My Care, My Way.

With the innovative approach to working in

partnership, HSCA’s are employed by Age UK K&C

and Senior Case Managers and Case Managers are

employed by Central London Community Healthcare

NHS Trust (CLCH). HSCA’s are line managed by

SCM’s or CM’s, CM’s are line managed by the

SCM’s and the SCM’s are line managed by the

Clinical Business Unit manager in CLCH.

As part of a collaborative approach to managing

both clinical staff and non-clinical frontline staff,

HSCAs are line-managed by the local Age UK in

Kensington & Chelsea, whilst Case Managers are

line managed by WLCCG

1. Background

Step 1. Patient is allocated to a practice-based Health and Social Care Assistant (HSCA) or Case

Manager (CM)

Step 2. Patient assessment conducted by HSCA or Case Manager, which includes:

- Recording of a Patient Activation Measure (PAM) on ‘SystmOne’ software

- Recording of goals for the patient’s Care Plan

- Completion of referral form with patient’s requirements and notes on their situation

- Direct referral to an appropriate service from the Self-Care directory of services

Step 3. Referral completion, where KCSC informs the VCS provider of referral details. The Provider

must contact patients within 7 days to double-check suitability, and commence first of six

service sessions.

9Social Return on Investment

Figure 1. Social prescribing for Self-Care services, within My Care, My Way (source: WLCCG)

WHAT IS

SELF-CARE?

SELF-CARE

PATHWAY

MCMW

CM’s & HSCA’s

SELF-CARE

PROVIDERS

KCSC

Awareness

Activities

& Support

Referral

Follow up &

Sustaining

change

Complete care plan

Use PAM to understand

patient's current level of

engagement

Use the directory or People

First website to identify

suitable activities and

support

MCMW

Primary care staff are

aware of self-care and

know how to signpost

patients through the

directory or People First

website

MCMW

PATIENT

Check referral criteria and

ensure the referral includes

information on any additional

support needed and patient’s

goals

Send referral form in S1 to

selfcare nhs email address

(tiers 2 & 3) or contact

services directly (tiers 0 & 1)

Add accepted referrals to charity log

Keep referral

criteria updated

MCMW

KCSC

Ensure that there is up to

date information about the

services on offer

KCSC

Contact patient for assessment

Email CM/HSCA if they can’t

engage the patient

PROVIDER

Check charity log to get progress updates

Respond to any issues raised by provider

MCMW

Collate patient’s feedback

from across the different services

KCSC

Keep charity log up to date

Email CM/HSCA with any concerns

PROVIDER

Review PAM two weeks

after the last session and

feedback to MCMW

Gather patient feedback

If needed contact

HSCA/CM by e-mail or by

phone, to discuss next

steps

PROVIDER

Check with the provider if

there is no feedback two

weeks after the final

session

Follow up with patient - and

develop a plan to help

them sustain change

MCMW

Assessment

& Care planning

6 sessions

Exercise

Counselling De-cluttering Carer’s support

Befriending

+ Social Clubs

Supporting

daily living

Diet

& Nutrition

Dementia

Support

Information

+ Advice

Self-Care Social Prescribing10

Referred patients can have up to six sessions of

their chosen activity or service. Patients can also

be re-referred once, giving access to a total of

twelve sessions.

The services provide a range of personal one-to-

one interventions and group activities. This ‘roster’

of services is demand-led, and so can change

depending on which types of services prove popular.

The five highest funded services during the pilot

phase (between May 2016 and March 2017) were

also the most popular: ‘Dementia 1-2-1 support’ (c.80

referrals), ‘Link Up’ (c.180 referrals), ‘Information and

Advice’ (c.155 referrals), ‘Exercise at Home’ (c.135

referrals), and Massage therapy (c.85 referrals).

Services provided during the pilot phase are briefly

described and categorised below:

African Dance

Group sessions to encourage physical activity,

balance, and inter-cultural awareness through

learning traditional African Dances.

Arts and Culture In The

Community (for dementia)

Activities range from group sessions for those

in residential care to one-to-one interventions

for people living in their own homes and at risk

of isolation. Activities include supported visits to

galleries, heritage buildings, and theatres that

enhance and compliment individual care plans,

and help people to feel part of their wider

community. Creative and cultural befriending

is also offered on a one-to-one basis.

Befriending

Weekly one-to-one visits to those patients who live

alone in Kensington & Chelsea and are at risk of

becoming isolated. People are able to keep in touch

with the outside world through their befrienders who

help to combat isolation by making regular visits

to older people, providing companionship and a

listening ear.

Carers Support Network

Provides a tailored service to unpaid carers,

informing and supporting them to identify their

needs and empowering them to make informed

choices and pathways for themselves and the

person they care for.

De-cluttering at home

Using proven de-cluttering techniques, the

personalised service assists clients wanting to sort

their belongings at home. This can be because they

want to downsize, reduce clutter, or reduce anxiety

about growing volumes of paperwork e.g. bills,

2. Services available

through social

prescribing

11Social Return on Investment

notices, official letters. This can help with reducing

the risk of trip hazards or fire traps, and can also

help those clients who require support at end of life.

Dementia One-To-One Support

The service offers personalised support in coming

to terms with diagnosis, providing activities that can

promote cognitive ability, slow disease progression,

and future planning. Interactive activities are

tailored to the client’s interests and abilities,

depending on their level of progression.

Escorting

Clients are provided with personalised assistance

to attend GP, clinic, hospital or other healthcare

appointments, with a trained person who

can accompany and travel from home to the

appointment, support and advocate during any

consultations, and ensure clients return home safely.

Exercise at Home

One-to-one tailored service with a case worker

with a health and fitness background, to undertake

gentle home-based exercise. Exercise plans can

help improve core strength, balance and flexibility,

increase confidence, promote cardiovascular

fitness, reduce stress, assist with weight control,

and reduce falls risk.

Information and Advice

Provides impartial and independent advice on a

range of issues, including Attendance Allowance,

welfare benefits, health, disabilities, housing

advice, social care needs, fuel poverty and energy

efficiency, family issues, and form-filling assistance.

‘Link Up’

Link-Up is a hub-based service, available to help

older clients access physical, creative and mentally

stimulating activities, to help improve the health

and wellbeing. A large variety of support activities

are available, both at home and in the community,

on a one-to-one basis or in groups.

Massage Therapy

Massage therapy is specifically for patients who

are frail, often isolated, and suffer from limiting

long-term conditions and chronic pain, but are

unable to easily access services through disability

or lack of mobility.

Macular Degeneration Support

Group

Provision of advice and support for people with

macular conditions and related sight-loss problems,

including age-related macular degeneration.

Memory Cafe

Social support group for people with memory

problems, and their friends, family, and carers.

Can include memory exercises, mental stimulation

activities, and general learning and interaction.

Men’s Only Activities

Hub-based peer-based group for supporting

men’s health and well-being behaviours, health

knowledge, socialising, cooking and nutrition,

and interactive activities in the community.

Nutrition and Community Lunches

Enables older people to attend healthy community

lunches and nutrition groups, to improve diet,

nutrition intake, and reduce social isolation.

Safety at Home and Falls Prevention

Provides support to people who, due to health

reasons or their living conditions, are at risk of

falling within their homes. The service aims to

reduce the risk of falls in the home, reduce harm

from other hazards in the home, recommend

the equipment or repairs necessary to improve

safety, and provide information and advice on

‘de-cluttered’, healthier lifestyles.

Self-Care Social Prescribing12

Supported Gym Sessions

Group or one-to-one sessions for light exercise

with patients, to build strength, cardiovascular

health, and mobility.

Walking Support

One-to-one support to get clients out and about

within their local communities at their own pace,

promoting wellness, building confidence, improving

balance, and reducing social isolation. This

may involve taking immobile clients out in their

wheelchairs, or proving guided walking support

for those using mobility aids such as sticks or

walking frames.

New services are added when there is a need.

New services for 2018 include opportunities for

gardening, and more cultural activities for those

with mental health illnesses.

2. Services available through social prescribing

Barbara’s

case study

Barbara previously had cancer twice and had

recently suffered a broken hip due to brittle bones

(partly due to intensive radiotherapy treatment).

She also suffers from cellulitis, resulting in one

leg being almost twice the size of the other. This

is extremely painful, heavy-feeling, and impedes

her walking. Barbara currently can’t get dressed

by herself and has carers who come to help with

her personal care.

As part of WLCCG’s My Care My Way

programme, Barbara’s GP – with whom she has

a very good relationship – initially called to ask

if she wanted to be part of the Self-Care project.

She was provided with a consultation with her

Case Manager. They discussed various options

to help with her rehabilitation and get out and

about in the community to build her confidence.

She recorded a PAM score with her Case

Manager of 55.7 and was referred to the walking

support service.

The walking support provider got in touch to

arrange her weekly sessions, and also to check if

she had any additional mental wellbeing needs.

For the first session, they went to the end of the

road and back – ‘not very far’. She had to rest

at the end. For the second session, Barbara

needed some shopping, so they walked a little

further to the supermarket. During later sessions

she was able to walk to the park and was getting

further with each session. Barbara felt the service

was flexible, and that her walking support worker

was very nice and kind.

‘ I hadn’t realised how difficult I would find holding

on to a stick and checking both ways for traffic.

I wouldn’t have been confident going out alone.

The worker is very patient when I need to stop

and rest. I was worried she would be marching

me up and down the road, but in fact she is very

kind, and not over-protective.

I just want to say how nice everyone is. Not

patronising at all. I’m very impressed, the attitude

of all staff – they want to help so much. Everyone

who I have dealt with in this service and in the

special unit at St Charles has been so good’

(a local integrated care hub).

Barbara’s motivation and confidence for her own

Self-Care improved significantly; her follow-up PAM

score improved to 67.8, an increase of 12 points.

She feels there is less risk of her falling and of

being isolated at home. Barbara is keen to continue

getting out and about, and is looking into walking to

French language classes near her home.

Patient’s name changed for confidentiality purposes

13Social Return on Investment

In May 2017, KCSC commissioned Envoy

Partnership to produce an Impact Evaluation with

a Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis of

the Self-Care social prescribing pilot. KCSC and

WLCCG felt this approach would provide the most

comprehensive and holistic form of evidence, as

it includes the identification and measurement

of outcomes for material stakeholders,

2

as well

as valuation of social (health and wellbeing) and

economic outcomes.

The key research themes in this evaluation are

as follows:

• Patients – Did the Self-Care pilot make a positive

contribution to patient confidence and motivation

to look after their own health?

• Carers and Families – Did the Self-Care pilot

make a positive contribution in supporting

patients’ carers and families?

• Cost Effectiveness – Did the Self-Care pilot

make a positive contribution to a reduction in

primary and secondary care use?

• Value for Money – What are the broader social

and economic impacts of the Self-Care pilot?

2

In SROI terms, material stakeholders are those who experience material outcomes, i.e. outcomes that are relevant and

significant enough to be measured, valued, and incorporated into the SROI model

3

A guide to Social Return on Investment, (2012), Cabinet Office. For more details, see socialvalueuk.org/resources/sroi-guide

• Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS) – Did the

Self-Care pilot enable the VCS providers to attract

or leverage in additional funding? Did the Self-Care

pilot facilitate wider strategic or organisational

change within provider organisations?

• KCSC – How effective is KCSC in harnessing

partnerships? As a result of KCSC as the

accountable body, are providers working together

in new, innovative ways?

A separate document containing a process

effectiveness report has also been produced as

part of our research remit, and this contains an

in-depth analysis of the efficacy of the Self-Care

model’s processes and structuring of activities.

The report is available from KCSC and WLCCG.

Social Return on

Investment methodology

Social Return on Investment is a type of cost-benefit

analysis that quantifies and values social as well as

economic benefits. The methodology followed in this

report directly draws on the UK Cabinet Office’s Guide

to Social Return on Investment .

3

SROI proceeds via

six distinct stages, as defined in the guide.

3. Impact evaluation

objectives and

method

Self-Care Social Prescribing14

SROI is a mixed methodology approach, relying

on both qualitative research (particularly in stage

2 below) and quantitative research (particularly in

stages 3 and 4 below):

4

Six SROI stages

1. Establishing scope and identifying

key stakeholders

2. Mapping of outcomes

3. Evidencing outcomes and giving them a value

4. Establishing impact

5. Calculating the SROI

6. Reporting, using and embedding

The Envoy research team conducted the SROI

research between May and November 2017.

The research was underpinned by the Seven

Principles of SROI as set out in the Cabinet Office

SROI Guide,

5

and shown in the box below.

Mapping a theory of change

SROI analysis involves the development of a

Theory of Change (under SROI stage 2 ‘Mapping

Outcomes’). This shows the stakeholders affected

by the Self-Care services, the inputs and activities

that occur, and the outcomes created by the Self-

Care pilot. The outcomes identified in the Theory

of Change are then measured. The measurement

focuses on the outcomes, i.e. the ultimate benefit

or change experienced by stakeholders, as well as

the outputs, i.e. the quantifications of activities e.g.

the number patients, or the number of episodes.

The Theory of Change is shown in section four.

Measuring outcomes for patients

To measure outcomes, we drew on validated

questions from existing clinical health

questionnaires, including EQ-5d, Warwick-

Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS),

PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), ICECAP-A,

and SF-12 (see Appendices Part D for details).

There are a range of methods to: i) measure

subjective wellbeing outcomes, and ii) value

subjective wellbeing outcomes. Often, the challenge

is to ensure that the outcome is measured in a

way that allows it to then be valued appropriately.

Our recommendation is that binary measures (e.g.

Yes / No questions) should be avoided; instead,

measures that show the magnitude of change

experienced by patients should be used. The

validated questions above fit this criterion.

Establishing impact

In SROI terminology, ‘Impact’ is a measure of

the difference made by the project or organisation

being evaluated. It recognises that there is

likely to be a difference between the change

observed, and the change for which the project or

organisation can claim credit. Such considerations

are important to ensure that the analysis does not

over-estimate value created.

Four key areas are considered here:

• Deadweight (what outcomes are likely to have

happened anyway)

• Attribution (the extent to which outcomes arise

because of social prescribing, rather than

because of the contribution of other people

or organisations)

• Displacement (whether any value is

‘displaced’ elsewhere)

3. Impact evaluation objectives and method

The Seven Principles of SROI

1. Involve stakeholders

2. Understand what changes

3. Value the things that matter

4. Only include what is material

5. Do not over-claim

6. Be transparent

7. Verify the result

4

Ibid., pages 9 –10

5

A guide to Social Return on Investment, (2012), Cabinet Office. For more details, see socialvalueuk.org/resources/sroi-guide

15Social Return on Investment

• Drop Off (the extent to which outcomes are

sustained over time)

The details for these considerations are further

explained in Appendices part B.

Primary data

The primary research conducted for this evaluation

is summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Primary research

The secondary data analysed for the evaluation is

as follows:

• WLCCG data regarding the average number of

GP appointments per year for all My Care, My

Way patients, in the period April 2016 – July 2017

• WLCCG aggregate data for MCMW acute

hospital episodes from 29 practices, in the period

April 2016 – March 2017

• WLCCG social prescribing PAM scores data for

the period April 2016-July 2017

• Insignia Health research into the impact of PAM

scores on patients

• WLCCG GP practice staff cost data

Data limitations

• De-identified acute hospitalisation data and

GP appointment data was shared by WLCCG

but was not made available by episode type

(e.g. specialist surgery, diabetes, cancer). We

therefore were only able to use unit costs for

average incidence costs.

• PAMs survey wording is seen by many patients

and practice staff as inappropriate for some

conditions, e.g. dementia. In these cases, PAMs

data was not collected; a simpler alternative

version would have been needed if data was to

be collected. Nonetheless, a reasonable amount

of data was collected; we received 247 baseline

and follow-up PAM scores to analyse.

• For certain outcomes, e.g. preventive effects

of interventions, our analysis is reliant on

subjective indicators through primary survey

data from HSCAs and Case Managers. This

data shows their perceptions on the extent to

which preventive effects are being achieved.

However, we remain confident with the results;

we achieved a sample of over half of the HSCA/

Case Manager population who were actively

referring. Improvements observed in PAM scores

for our sample also provide confidence that a

significant proportion of patients benefit from

reduced need.

• We did not receive patient postal survey returns

for all services, particularly for those with a low

number of referrals. There were no returns from

T’ai Chi, African Dance, or community lunch,

for example.

Stakeholder groups Sample Methodology

Qualitative

Patients

(Tiers 2 and 3)

33 Face-to-face

interviews,

often in the

patient’s home

Case Managers

& HSCAs

31 Telephone

interviews

VCS providers 9 Face-to-face

interviews

Statutory authorities

(public health,

adult care)

3 Face-to-face

interviews

GP lead for

Self-Care

1 Telephone

interview

WLCCG managers

for Self-Care

2 Face-to-face

interviews

Quantitative

Patients

(Tiers 1,2,3)

134 Paper survey

delivered by post

Case Mangers

and HSCAs

(75 actively referring)

42 Online survey

Self-Care Social Prescribing16

Service themes and patient outcomes

In our research, we identified different categories of services that led to slightly different groups of

outcomes, as shown below in Table 2:

Table 2: Patient benefits from Self-Care services

Service theme Patient outcomes

Physical & Exercise activities

• African Dance

• Escorting

• Exercise at Home

• Massage Therapy

• Supported Gym Sessions

• Walking support

Physical wellbeing

Reduced isolation

Mental and Emotional wellbeing

Reduced anxiety

Maintain independence

Respite for patients’ carers (during patient sessions)

Mental wellbeing and reduced isolation

(non-dementia specific)

• Befriending

• ‘Link Up’ activities

• Memory Café

• Men’s Only Club Activities

• Carers Support Group

Reduced isolation

Mental and Emotional wellbeing

Reduced depression

Reduced anxiety

Maintain independence

Memory retention

Respite for patients’ carers (during patient sessions)

Dementia-specific support

• Arts and Culture in The Community (for dementia)

• Creative and Cultural befriending

• Dementia One-To-One Support

N.B. Exercise at Home and Walking Support are also

provided to dementia referrals with a tailored approach

Mental stimulation and concentration

Reduced isolation

Reduced depression

Mental and Emotional wellbeing

Improved Self-Worth

Reduced anxiety

Maintain independence

Respite for patients’ carers (during patient sessions)

Safety & Welfare Information and Advice

• De-cluttering at home (can also be considered as

part of mental wellbeing services)

• Safety and falls prevention at home

• Information and Welfare support advice

New source of income support

Reduced anxiety

Maintain independence

Physical wellbeing

Improved living conditions

Respite for patients’ carers (during patient sessions)

Health Education & Nutrition

• Healthy Lungs

• Macular Degeneration Group

• Nutrition and community lunches

Physical wellbeing

Reduced isolation

Maintain independence

Improve health knowledge

4. Findings:

Patients

17Social Return on Investment

Chart 1 shows the proportion of referrals by service

theme for the pilot period (Apr ‘16 – Mar ’17).

The largest categories of referrals were physical

activity, mental/emotional wellbeing and isolation,

and information/advice and safety at home.

Chart 2 illustrates that the majority of referrals for

the pilot period were comprised of Tier 2 patients

(almost 53%) with just over a third from Tier 3. A

much lower proportion of 7.6% were Tier 1 patients.

Chart 1. Referrals by service theme,

Apr 16 – Mar 17

Chart 2. Referrals by Tier,

Apr 16 – Mar 17

Patient referral proportions by service type

(n=807)

31.1%

Physical activity

& exercise

29.6%

Mental/Emotional

Wellbeing &

Isolation

4.8%

Health Education

& Nutrition

0.9%

Carers

Support

34.6%

Tier 3

7.6%

Tier 1

5.1%

Unknown

52.8%

Tier 2

22.6%

Info & Advice +

Safety at Home

11%

Dementia

specific support

Patient tier proportions (n=807)

Self-Care Social Prescribing18

Outcomes for patients

Much of the benefits to patients come through

re-building their balance and self-confidence in

their mobility (e.g. when being able to walk around

outside or at home), and through reducing pain

and discomfort, improving their support networks

and social networks, and reducing levels of

depression or anxiety. Across most of the service

themes, patients feel they have benefited from

reduced levels of anxiety about their condition(s)

or health situation, and have also felt more valued

by others – especially by the health care system.

Reduced social isolation, and improved re-

connection to their community, are also particularly

important for patients. Some patients felt that

maintaining their ability to live as independently

as possible was important, although for many

others who are extremely frail and housebound,

this may not be a realistic outcome. Maintaining

independence at the same level is a good outcome

for many.

Outcomes for Carers and Families

Evidence collected from interviews and surveys

suggests that informal carers of patients gain

some relief of around one hour during each of the

patient’s sessions. In most cases, carers will either

use the time to continue with other tasks regarding

the patient’s care needs or day-to-day tasks

around the patient’s home. Some will use the

time for respite.

15 from 134 patient survey responses fed back on

respite for carers. Around half of these responses

indicated that the Self-Care service was moderately

to extremely helpful for creating respite time for

carers. However, this is a small sub-sample, and

the research indicates that the more significant

outcomes actually relate to the carer feeling

happier for the patient, if the patient feels better in

themselves or if their health condition improves.

When information and advice support (from CAB

Westminster and Age UK), leads to successful

claims for welfare payments, there is a longer-term

impact on carers, both in terms of relief, and their

wellbeing. This appears to be a stronger outcome

for carers who are the spouse or partner of the

patient, and sometimes have their own health

conditions to manage.

For the small number of cases where referrals

were made for the carer to access specific support

through the Carer’s Support Network, the most

important outcomes were:

• Reduced feelings of being isolated and alone

• An improved awareness about other

available support

• Better able to navigate a plethora of health

agency/service material and contact details,

that they would otherwise feel overloaded with

There was some less positive feedback from

carers. In some cases, carers express frustration

and disappointment with health professionals and

statutory support, claiming inadequate information

about Self-Care from their GP and a disjointed

approach between housing support, GP practices,

and social care.

4. Findings: Patients

‘ The professionals from housing, health, social

care, all look at our case one-sided, from

only their viewpoint and how it affects them,

rather than communicating and helping each

other to avoid conflicting decisions for my frail

parents…I’m upset my GP didn’t mention these

services [social prescribing] in the first place.’

T.B., son and carer of frail parents

19Social Return on Investment

‘ From the experience of family members’ illness, a map/picture of introduction information might help

people to understand A) how to get help from whom in a ‘direction’ guide. B) how NHS care system

works in the relation with hospital, local council, nurses, and GP, and C) Basic knowledge of ‘NHS

uniform’ meaning.’

Carer and relative of patient receiving Exercise at Home and Walking Support

Tej and his parents

case study

Tej is a full-time carer for his elderly parents, who

are extremely frail and housebound (‘Tier 3’ frailty).

His parents also suffer from poor mental health.

His father’s condition means he is unable to speak

at all, and his mother is unable to speak English.

Tej had to go through a lengthy process to

obtain a Power of Attorney to represent his

parents at their local health services and GP

surgery. At one consultation, front-desk staff also

recommended he attend a further consultation

with a HSCA, to explore if there were other

community-based services appropriate for his

parents. After identifying the condition and needs

of his parents and recording a PAM score on

their behalf (c.70), the HSCA suggested either

exercise at home or massage therapy, to help

support his parents’ overall wellbeing, mobility,

and strength in their joints and muscles.

Tej was referred and contacted within a week

by the provider for exercise at home, to arrange

the session plans for his parents. This required

Tej to be available during the sessions to

translate some of the instructions, session

planning, and to help ensure his parents were

comfortable with a stranger in the home. The

exercise instructor guided them through gentle

exercises, which mostly focused on limbs, arm,

hand, and neck exercises. It was important that

the provider enabled each of his parents to feel

they were making progress at their own pace

and within their respective capabilities, whilst

the intensity increased a little for each session.

After completing the sessions, Tej felt his parents

were a little stronger and benefitted from better

sleep. However, they still felt some pain, anxiety,

and blood circulation problems; and so Tej also

requested massage therapy at home, on his next

HSCA appointment.

The massage therapy provider contacted Tej

within a few days, and had sessions scheduled

for both parents, one after the other at home.

Tej described is parents as ‘uncertain aft first,

especially have a different female [the therapist]

in the home…but she [the therapist] was very

sensitive and understanding…they [parents]

loved and enjoyed the massage service, I can

see them much happier and responsive mentally,

even after just the second session…the pain

reduced for them and they are more relaxed than

before…and now [it’s] a little less difficult to move

them [around the home, or from sofa to bed],

and they are more peaceful’.

Tej felt that it was important for all frail, older

people to have access to more services like

those made available to his parents, especially if

it gives a boost to carers to see their service user

or relative benefitting so tangibly. Tej is following

up with his HSCA about receiving more carer

support, and exploring how to arrange more

ad hoc sessions at home for his mother.

Patient’s name changed for confidentiality purposes

Self-Care Social Prescribing20

Theory of Change

In an (SROI) analysis, qualitative research from

stakeholder engagement should inform the

creation of a Theory of Change. The Theory of

Change is the foundation for identifying which

stakeholder outcomes should be measured and

valued. It presents stakeholders, activities, and

outcomes that arise from the social prescribing

model. It can be useful for helping understand the

different pre-conditions that exist, and for helping

understand where potential barriers to change

might occur. It aligns with HM Treasury Magenta

Book guidance on logic mapping.

6

Figure 2 shows the Theory of Change for the

Self-Care pilot. It summarises the outcomes

for material stakeholders arising from core

activities of the Self-Care model. It shows

how the activities lead to outcomes, and how

short-term outcomes lead to long-term outcomes

which should be valued.

We have presented a theory of change for the

whole Self-Care pilot, across all the services

provided. Not all of the patient outcomes will be

applicable for all of the patients. The left-hand side

of the Theory of Change maps the main activities

that preceded referrals into the social prescribing

services. These then build from left to right into

the short to medium term outcomes, and to the

long-termer outcomes, which we define below:

• Short-term to Medium outcomes are those

that can happen during the sessions or in the

first month after all sessions are completed

(including re-referral).

• Long-term outcomes are those that are

expected to arise around six months after

the sessions are completed.

As services are paid for from the contract budget

to VCS providers, they are treated as part of the

overall inputs to the activities. It should be noted

that outcomes for carers discussed in the previous

section of this report were not monetised in our

analysis, due to relatively low referral numbers

for inclusion in our postal survey.

Changes to Patient Activation

Measures (PAM)

One objective of Self-Care is to improve patients’

activation and motivation about managing their

own health and wellbeing. Patient Activation

Measures (PAMs) are designed to help medical

services to understand whether patients’ activation

and motivation has changed. PAMS are recorded

by practice-based staff with patients, to track

their levels of activation and motivation. This is

important as part of My Care My Way’s drive to

educate and empower older patients to self-

manage their conditions as much as possible.

We received WLCCG data for over 2,000 social

prescribing PAM records across 2016 – 2017.

However only 247 patients had both baseline

and follow-up scores in this period. Of those

patients who had follow-up PAM scores, around

62% showed an improvement. The average

improvement for those 62% was 5.8 points.

According to the PAM scoring system,

7

an

improvement by one-point correlates to 2%

reduced hospitalisation likelihood. Therefore,

one of the areas of resource savings indicated by

the improvement in patient activation would be an

average 11.6% rate of reduced hospitalisations,

for patients who showed an improvement.

PAM scores are presented by Tier level in Table 3.

There are only marginal differences between Tier 2

and Tier 3.

4. Findings: Patients

6

The Magenta Book: Guidance for Evaluation, HM Treasury (2011) see logic model in Chapter 5

7

Licensed from the US company Insignia Health

21Social Return on Investment

Figure 2. Theory of Change for the Self-Care social prescribing model

Patient arranges visit to GP practice

re: non-medical health/wellbeing issue

Consultation with HSCA or

Case Manager instead of GP

to discuss needs

Provider contacts

patient to arrange

and manage sessions

Provider logs case

notes and updates to

Charity Log software

Provider may arrange appropriate

forward referral to other services

or sources of support

Patient referral logged with

KCSC; patient needs,

background, goals shared

Select service from Directory

- Provider 1 - Provider 3

- Provider 2 - Provider 4 etc

- Carer relief in short-term

- Less alone/isolated in short-term

- Improved knowledge to better

navigate care services

- Sustained tenancies for housing

providers of patients

- Avoid patient need for entering

long term care home

- Provider provides 6 sessions to

patient (1-2-1 basis or Group activity)

- Provide health guidance & coaching

- Develop service directory

- Select and recruit services

- Manage contracts and payments

- Manage overall capacity

- Co-ordinate referrals

- Record data and track activities

-Learning and knowledge-sharing

- Connect local VCS networks

- Reduced pain and discomfort

- Reduced depression

- Reduced levels of loneliness and social isolation

- Improved self-confidence/self-worth

- Improved independence

- Feeling equally valued by health services

- Avoided GP consultations

- Avoided HSCA & CM research

and consultation hours

- Reduced hospital spells

- Reduced outpatient clinic visits

- Avoided A & E incedence

Care plan update with

involvement of patient

KCSC co-ordinates referral

and notifies selected Provider

- Diverted GP hours

- Diverted HSCA & CM research hours

Patient may choose to

discontinue sessions

Some patients health

may deteriorate anyway

Self-activation

(self care)

Feedback

Loop

Provider resourcing,

staff times and training

Short to Medium Term Long Term

Legend:

Health service activities

KCSC activities

VCSS Provider activities

Outcomes – patients

Outcomes – health services

Outcomes – carers & relatives

Outcomes – statutory services

Outcomes – other

Self-Care Social Prescribing22

4. Findings: Patients

Table 3: Change in PAM scores of the

62% of Self-Care patients showing

an improvement.

n=247 for Self-Care patients with baseline and

follow-up scores, n=151 for those who see

an improvement.

PAM results also indicate that approximately 38%

of referred patients either experienced no change

in activation, or a reduction in activation. The SROI

model assumes that this reduction in activation

would have occurred anyway; the age and frailty of

many patients means that a reduction in activation

over time might be expected. The qualitative

research gave no indication that the services

significantly reduced activation, and the survey

responses from Case Managers and HCSAs

indicate that the proportion of patients whose

health got worse as a result of the Self-Care

intervention is negligible.

8

Furthermore, the SROI model may under-estimate

the positive impact of the Self-Care pilot. For

those patients who experience an increase in

PAM score, it might be that their PAM score would

have fallen without Self-Care, meaning that Self-

Care’s impact would be greater than stated here.

Likewise, for those patients who experience a

decrease in PAM score, it might be that their PAM

score would have fallen even more without Self-

Care. Without data from a control group, getting

a credible estimate of such change is difficult.

8

See section 5

PAM scoring is not necessarily an indicator of

health. Improvements in patient activation and

motivation do not necessarily result in improved

health outcomes in all cases – but receiving a

Self-Care service may have helped those patients

manage their condition better and maintain

important aspects of their quality of life, even

if there has been no increase in PAM score.

Measures of change for patients

In addition to evidence collected through

qualitative interviews, we also collected 134 patient

surveys across different Self-Care service themes

(Table 2). The aim was to quantify the outcomes

identified in the qualitative research. The measures

are presented below in Chart 3 and Table 4.

Tier 3 Tier 2 Tier 1

+ 5.9

(51.1 to 57.0)

+ 6.4

(50.2 to 56.6)

+ 3.2

(56.8 to 60.0)

‘ Very good and I have no suggestions to

make. My main adversary is laziness – hardly

your fault!’

‘ I think Men’s Only activities do a wonderful job,

it is just what I need to motivate myself into a

better and healthier way of life’

‘ A wonderful idea to keep the elderly [like me]

active and motivated.’’

Self-Care patients’ feedback

‘ Linking patients in with activities, or the

increased level of interaction provided by

services such as walking support etc – very

clearly improves outcomes in terms of

emotional wellbeing and isolation.’

HSCA feedback, Kensington & Chelsea

23Social Return on Investment

9

As corroborated by PAM improvements: see Table 3

Table 4 Shows patients’ responses on pain,

depression and anxiety. We can see increases in

the proportions of patients who feel: i) No pain or

little pain (+24%), ii) No feelings of being down or

depressed (+17%), and iii) No feelings of anxiety

(+14%). Survey questions in Table 4 were based

on the short EQ5-d and PHQ9 surveys.

Table 4. Patient survey responses regarding

health status outcomes

Chart 3 shows patients’ level of agreement with

statements regarding their well-being, both before

and after the Self-Care service. The largest change

(67% to 78%) was in patients’ sense of self-worth

and motivation to take care of their own health and

medication,

9

and feeling more valued by the health

care system. Before their Self-Care referral, 63%

felt as valued by health services as other people.

This increased to 69% after their referral.

There is also a small reduction in isolation, with

slightly more patients reporting they had enough

people they personally felt close to in their lives

after the service (69%) compared to before (65%).

Chart 3 also indicates that there are small changes

for independence and dignity. For many of the

patients, there appears to be a lower starting

point for the ‘Before’ referral score for living

independently, relative to other indicators. It was

clear from our interviews that maintaining the

independence that they have is a good outcome

for many patients.

Chart 3. Patient’s self-reported change in well-being

I feel motivated to

take care of my health

and medication needs

I can live as

independently as I want

My living conditions

help me to live in dignity

There are enough people

I personally feel close to

When accessing health

and care support I feel

I’m valued just as much

as other people like me

Before

Strongly Agree

3

%

1

%

Neither Agree nor Disagree Strongly DisagreeDisagreeAgree

Before

Before

Before

Before

After

After

After

After

After

Q. “Please put a cross (X) in the box that best describes how much you agree or disagree with each statement below:”

All self-care patients responding to survey, Nov/Dec 2017. n=89, 98, 87, 95, 68, 78, 77, 85, 85, 94.

9%52%

29%

4%5%

7%54%31% 5%4%

7%22%45%22% 4%

13%54%24% 5%

17%15%46%19% 2%

12%18%40%29%

9%

9%

5%

4%

17%

21%

7%

5%

20%

12%

24%

22%

38%

41%

48%

50%

17%

17%

15%

19%

% of Patients

responding Before

After Change

Little or No pain 15% 39% +24%

No feelings of

being depressed

30% 47% +17%

No feelings

of anxiety

29% 43% +14%

Self-Care Social Prescribing24

SROI requires the monetisation of social,

environmental and economic outcomes.

10

Patient

wellbeing outcomes valued in our analysis are

as follows:

• Reduced pain and discomfort

• Reduced depression

• Reduced levels of loneliness and social isolation

• Improved self-confidence/self-worth

• Improved sense of health equality i.e. feeling

equally valued by health services

• Improved independence

Approach to valuation

Our approach to valuing patient outcomes are

based on Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY)

approaches to valuing health. These align with

similar approaches used by both WLCCG, and

the NHS and the National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (NICE) more broadly. In

terms of QALY value, we have used the British

Medical Association’s guidance from their recent

paper about preventive intervention, Exploring

the cost effectiveness of early intervention and

prevention (2017). This states that NICE considers

interventions costing up to £20,000 per QALY

gained as cost effective. The BMA also refers to

a NICE analysis on 200 interventions between

2006 and 2010, where 70.5% (i.e. a clear majority)

costed less than £20,000 per QALY gained’.

We drew on a range of sources for valuations.

These value ranges are described in the Appendix

Part C. These included Devlin, Shah et al, from

the Office for Health Economics and University

of Sheffield, published in the Journal of Health

Economics (JHE) in 2016,

11

and Jia and Lubetkin,

in the journal, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

(2017).

12

We also drew on guidance from other

research (New Economy Manchester; and Bield

Housing, Hanover Scotland and Trust Housing),

13

in

order to attach value ranges to the overall measures

of patient wellbeing. The value or worth of subjective

wellbeing is termed ‘utility’ in the JHE research.

5. Findings: Valuing the utility

of patient health

and wellbeing

outcomes

10

However, environmental outcomes are out of scope of our research as they were deemed immaterial

11

Valuing health-related quality of life: An EQ-5D-5L value set for England (March 2016)

12

Incremental decreases in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for U.S.

Adults aged 65 years and older (2017)

13

New Economy Manchester (2012) Understanding the Wider Value of Public Policy Interventions, and Bield, Hanover and Trust

Housing (2012) SROI of Stage Three Adaptations, and SROI of Very Sheltered Housing

25Social Return on Investment

Through applying these value ranges to the

amount of change experienced by patients, we

calculated the values of the outcomes experienced

by patients. The values are presented by service

category total, and on a per patient average basis,

in Table 5. The results account for attribution

adjustment, to reflect that patients recorded c.23%

attribution to the services for the overall impact

experienced (see Appendices Part B, and also

section three).

Our results indicate that services supporting

physical activity and exercise, and mental

wellbeing and isolation tend to generate higher

values, both per patient and overall. However,

Table 5 also indicates that dementia-specific

support has a relatively high ‘per patient’ value,

even though there were fewer referrals.

Table 5. Attributable values for patients’

health and wellbeing outcomes, pilot year

to March 2017 (rounded)

*Excludes new welfare payments to patients of c.£112,000 in total

According to our patient survey, around one in

four patients who received Information and Advice

support went on to receive welfare payments. The

average amount received by patients was c.£2,732

per year. Most payments were Attendance

Allowance payments (e.g. payments to attend

health appointments when it is physically difficult to

do so without support), and smaller allowances for

energy support.

Service category

Overall Health

and Wellbeing

value per patient

pre-attribution

Health and

Wellbeing value

per patient after

attribution

Number of

patients

Attributable

Health and Well-

being Value –

All patients

Physical & Exercise £1,330 £290

251

£73,500

Mental wellbeing

& Isolation

£1,000 £230

239

£54,500

Safety at home

& Welfare

Information/Advice*

£330 £70

182

£13,000*

Health Education

& Nutrition

£50 £10 39 £400

Dementia-specic

support

£1,280 £280 89 £25,000

Self-Care Social Prescribing26

Moira’s

case study

Moira has dementia, lives alone, and needs her

walking stick to walk for long periods. Her HSCA

at the local GP clinic identified Moira’s strong

interest in arts and culture and that she was

comfortable interacting with other people. As

part of her consultation and Care Plan, to avoid

the negative effects of loneliness and isolation

on her dementia, Moira’s HSCA referred her to

attend arts and culture activities for people with

dementia. The service contacted Moira and

clearly explained how the activities would work;

what support would be available for her during

the activity; they provided clear instructions

and directions to attend; and followed up with

a reminder through her support worker. This

encouraged Moira and put her at ease.

The service enabled Moira to attend dementia-

friendly group activities at various culture and

arts venues. This included visits to art galleries,

Kensington Palace, and an opera production in

Holland Park – with a backstage tour with the

opera singers. At the activities, the provider’s

session workers are posted at different locations

at the venue and near the entrance, to welcome

participants, help with wayfinding, and help find

resting points.

There are often many interactive components

of the activity, which requires input and sharing

of ideas and stories between participants, as

well as learning from speakers or learning from

people working at the venue e.g. a costume

and set designer, an opera conductor, or a

heritage specialist.

This really suited Moira, who has a sharp sense

of humour and has a fun-loving personality, and

is keen to get involved and learn the value of

objects and artefacts. The activities are designed

in a way which enables her to be engaged with

by friendly staff and group participants, and

to participate in creative activities, including

art work, walking tours, music, and singing.

She stated that some of the experiences with

Resonate were ‘just wonderful’ and that she felt

‘very lucky to join in…it’s so nice to be with such

special people [including the volunteers]’. Moira

continues to access the service ‘on her own

steam’ as this is one of her only opportunities for

combining social interaction, enrichment, and

mental stimulation. It gives her ‘quite a boost

to feeling good…and builds confidence’ when

managing her condition.

5. Findings: Valuing the utility of patient health and

wellbeing outcomes

Patient’s name changed for confidentiality purposes

27Social Return on Investment

Major priorities for GP practices taking part in

the Self-Care pilot include tackling diabetes

(for example, through improvements in active

lifestyle, diet, and medical compliance), managing

dementia, and reducing the effect of social and

emotional isolation on older patients’ overall

wellbeing. The service themes within the social

prescribing directory therefore seem appropriate

as they contribute towards supporting patients

with these health problems.

HSCAs and Case Managers reported back on the

health status of patients now, compared to before

their referral. Table 6 shows the average proportion

of patients who have improved. Improvement was

higher for Mental Wellbeing than Physical health.

Within Physical health the proportions for ‘Much

better’ health were highest for Tier 2 and Tier 1.

Proportions of patients who had got worse after

the service were negligible.

Table 6. HSCA and Case Manager survey

responses on physical health and wellbeing

status (n=42)

The ‘Much better’ responses corroborate well with

proportions indicated by patient survey results.

Conversely, a lower proportion of HSCA and

Care Managers (38%) agreed that their GPs

recognised the VCS providers as partners in their

work. Even fewer (36%) agreed that GPs had a

clear appreciation of the outcomes from social

prescribing referrals. This suggests that some

knowledge barriers may exist around the benefits

of cross-sector collaboration and recognition about

the Self-Care social prescribing model.

To compound this challenge, in our analysis of

process effectiveness, we also observed that

there is a need for effective feedback to be more

regularly recorded, and accessed by practices. This

is especially important as GPs are accountable

for their patient Care Plans. Currently there are

two software systems where a lot of information

is recorded but needs to be better integrated:

‘SystmOne’ (used by health services) and ‘Charity

Log’ (used by VCS case partners).

6. Findings:

Health and

Care system

Health status summary

Physical health NOW

vs before referral

Mental wellbeing NOW

vs before referral

Tier 3 Tier 2 Tier 1 Tier 3 Tier 2 Tier 1

% of referrals ‘Much better’ 3% 10% 27% 20% 33% 34%

Total % of referrals ‘Much better’

and ‘Somewhat better’

58% 70% 66% 83% 91% 90%

Self-Care Social Prescribing28

Preventive impacts

The research highlighted a number of preventative

impacts of the Self-Care pilot. Case Manager

and HCSAs gave estimates of the proportion of

patients who stopped the need for frequent GP

visits; this is presented in Table 7 below. Case

Managers and HCSAs indicate a lower proportion

for Tier 3 than Tiers 1 or 2. We have used this

lower proportion (23%) to avoid over-claiming

in our calculations. Our calculations therefore

estimate this to be the equivalent of 185 patients

stopping the need for GP appointments during the

pilot period.

Table 7. Case Manager and HSCA

perceptions of proportion of patients stopping

the need for frequent GP visits (n=42)

According to WLCCG data for older patients

across all of My Care, My Way, the average

number of GP appointments per year is 30 per

patient (excluding no-shows).

In addition, we collected HSCA and Case Manager

perspectives on the preventive effect of the Self-

Care model. By preventative effect, we mean

reduction in health deterioration and the need for

other services in the future. The results are shown

in Table 8.

Table 8. Case Manager and HSCA survey

perceptions of preventive effect of services

(n=42)

Outcomes for health and

care services

In order to quantify the preventive impacts in more

detail, we have analysed data from WLCCG for

GP appointments and acute hospital incidences

across My Care, My Way, and triangulated this with

PAM score data and our survey findings. There are

also number of key considerations arising from our