DEMYSTIFYING THE THESIS

Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

Richard Willson, Ph.D. FAICP

Department of Urban and Regional Planning

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

Version 2.2, Draft, July 28, 2022

1. Introduction

The thesis option in the Master of Urban and Regional Planning (MURP) program provides an opportunity

to develop expertise in a planning topic, contribute knowledge to the profession, demonstrate facility with

research methods, and showcase writing and organizational skills. For those entering practice, it is the best

example of your ability to generate knowledge to improve plans or policy. For those planning to pursue a

Ph.D., it is the strongest demonstration of your potential as a researcher. For all career paths, the thesis

provides evidence of your planning interests, skills, and ability to work independently.

This guide provides advice on the process of undertaking a thesis in the Department of Urban and Regional

Planning (URP) at Cal Poly Pomona (CPP). You should interpret this advice in consultation with advisors

because of the wide variety of planning subjects, analysis frameworks, and methodological approaches.

The thesis preparation course, URP 6902, further develops the themes outlined here.

Demystifying the Thesis was written with the input and advice of URP faculty. While individual thesis chairs

will surely deviate from elements of this guidance, this is our collective best advice. This advice

supplements the written requirements of the CPP University Catalog and the URP Graduate Program

Guide. Those are the determining documents in any instance of differing advice being offered here.

The document addresses the definition of a thesis (Section 2), how to initiate your thesis (Section 3),

working with your committee (Section 4), a sample schedule (Section 5), topic selection (Section 6),

literature reviews (Section 7), writing quality (Section 8), and methodologies (Section 9). The appendices

include technical writing tips (Appendix A) worksheets and prompts to explore topics (Appendix B – D),

outside sources of information (Appendix E), and commentaries from alumni who have completed their

thesis (Appendix F).

The thesis process provides freedom in selecting a topic and research approach that is beyond that which

you may have experienced in previous classes. You are not paid to complete it and are not responding to a

client’s agenda. You have freedom within the bounds of scholarly questions and methodologies. Of course,

this may seem like too much freedom since so many approaches are available, but your thesis chair will

help you through the process. Your research problem must be responsive to the literature, technically

doable, and sufficiently interesting to you. It must respond to a knowledge deficit in the field.

You will use the problem formulation, research design, and research implementation skills developed in the

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

2

thesis experience throughout your career. For example, developing a specialized expertise will support your

job search. Knowing how to conduct a literature review will allow you to efficiently tackle new issues. The

thesis experience also makes you a more discerning user of others' research. Lastly, an outstanding thesis

can be the basis for a publication, ensuring your knowledge contribution to the field.

1

Concerning the process, students who meet regularly with their Spring semester URP 6960 chairperson

tend to enjoy the process. In my experience, students who are in touch with their advisor once a week and

define regular work products generally complete the thesis within schedule. Because it is a self-managed

process, it is easy for deadlines from other courses, work, and your outside life to derail thesis progress.

Procrastination can also occur when you feel uncertain about the scope of your project. This class is

intended to help with that.

Think about potential thesis topics early and discuss them with potential chairs during your first year of

study. Then you will take the thesis prep course, URP 6902, with some momentum. The course will lead

you through the process of developing a thesis proposal, but give yourself plenty of time to refine and,

inevitably, narrow your topic.

If you have a topic and potential committee members in mind before you enroll in URP 6902 you can

identify and screen potential topics, review previous research, assess data availability, and do some

groundwork in other class papers. That will also provide adequate time to obtain comments on the topic

from potential committee members, planners, and other interested parties.

Examples of recent MURP theses can be viewed at https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/catalog Filter by CPP

and Department of Urban and Regional Planning. Note that both capstone theses and projects appear in

this section. Sometimes the normal length of the finished thesis is intimidating to those starting out, but

once you realize how the thesis document explains each step of the process and the results, this concern

often recedes.

2. What a Thesis Is and Is Not

Many students have misconceptions about the thesis. Some believe it is like writing a book. It is not. A book

usually synthesizes numerous individual research projects and is therefore broader and more synthetic. A

thesis is focused, organized around one or a small group of questions or hypotheses. Here is the Cal State

University definition of a thesis:

… A thesis is the written product of a systematic study of a significant problem. It identifies

the problem, states the major assumptions, explains the significance of the undertaking,

sets forth the sources for and methods of gathering information, analyzes the data, and

offers a conclusion or recommendation. The finished product evidences originality, critical

and independent thinking, appropriate organization and format, and thorough

1

The following are example URP theses that have summarized and published as journal articles:

Alexander, Serena. 2014. “Campus Climate Action Plan Legacies and Implementation Dynamics.” Planning for

Higher Education 42 (3): 42–57.

Okashita, Alex and Richard Willson. 2019. “Impact of Market-Rate Residential Parking Permit Fees on Low-Income

Households.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. DOI:

10.1177/0361198119878381.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

3

documentation. Normally, an oral defense of the thesis is required.

2

A thesis also displays your ability to communicate effectively in writing and orally. If you are concerned

about your writing abilities, see the Graduate Coordinator to discuss remedial steps. Your oral abilities are

demonstrated in the thesis defense, a one-hour meeting in which you summarize your methods and

research findings and respond to the committee's comments and questions.

To accomplish the above with sufficient depth and rigor, the research topic and problem may be more

narrowly defined than you might initially suspect. A thesis advances knowledge in a focused area beyond

that accomplished by other scholars. The single biggest problem students encounter is not defining a

sufficiently focused topic that can be addressed through the research approach. A focused topic means that

you conduct original research to address it; it is not just rehash of others' work.

Many students fear focusing because it seems initially that they couldn't possibly write "x" pages on what

seems like a narrow topic. Once you start, however, you will find that there is plenty to write because only

when you commence will you discover all the issues that must be addressed. A caveat to the focus

recommendation is that the topic must be of sufficient interest to be appropriate for a thesis. If there is not

a substantial problem, issue, or knowledge gap in the literature or the profession, then you don't have a

topic yet.

The emphasis on depth and rigor does not mean that a thesis must be quantitative. Qualitative research is

equally valid as long as it is undertaken in an appropriate manner. Qualitative research is in some ways

more challenging than quantitative research because procedures are less standardized and the criteria for

judging the validity of findings are more debatable. Another option is a mixed-methods approach that

combines quantitative and qualitative research.

A thesis is not a plan. Plans memorialize goals, objectives, and policies and/or set out implementation

steps. Although plans may contain or be based on research, original research is not their primary purpose.

Except under rare circumstances, a thesis is not an integration of preexisting knowledge. However, a thesis

can apply existing knowledge to a new problem.

A thesis is not a work product from your planning job. It is, however, appropriate to use data sources and

contacts you may have at work. For example, if you are collecting data for a Specific Plan at work, you could

use that data to explore a more focused research question.

Be modest about the breadth of your research and ambitious about the level of detail you will pursue. You

will undoubtedly have ideas about issues that are not within your defined topic. Rather than letting the

focus drift, keep them in mind and list them in a “future work” or “related questions” section at the end of

the thesis.

There is tension between this advice and the nature of the MURP curriculum. We teach you to look at

planning issues comprehensively—to be concerned with physical, social, and economic aspects of a

problem. The planning curriculum draws from fields wider than most disciplines: anthropology,

architecture, business, cultural studies, ecology, economics, engineering, geography, history, landscape

architecture, philosophy, policy sciences, political science, public administration, sociology, urban design,

2

Title V, Section 40510 definition for California State University system.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

4

and other fields. As a result, some students bring this broad approach to their thesis. This may cause

difficulties with excessively broad or weakly defined topics. Difficulties with broad topics include excessive

generalizing, a lack of evidence, and/or confused organizational structure. The project may become

unmanageable. Research findings are essential in plan development, but it is the planning process that

synthesizes and uses the research findings.

3. Initiating Your Thesis

Early in the program, undertake the following steps:

• identify your general research interests and their relationship to your professional aims;

• identify multiple potential topic areas;

• identify alternative research questions within those topic areas;

• conduct a preliminary literature review in those topic areas;

• consider and develop your methodological talents

• explore the availability of information and data sets;

• seek the advice of faculty and professionals who have expertise in the subject area; and

• talk to planners about their reaction to the topics.

Reading and writing are two essential methods for exploring topics. Read the Journal of the American

Planning Association, Journal of Planning Education and Research, The Journal of Planning Literature, and

other applicable journals to determine the status of current research in your field. Make a practice of

examining the articles for their hypotheses, methodologies, key findings, and literature reviews. A very

recent article in your topic area can ease the search for important references because they will likely be

cited in that article. Note that Google Scholar searches tell you the number of times an article has been

cited by others, which provides a clue on the influence of a particular article. For practice-oriented

research, attend an American Planning Association conference or seminar and track down those who have

an interest in your potential research. Get their comments and advice.

You may feel that there is no prior research in your area, but that is rare. Find the important journals in the

subfield, undertake a keyword search for journal articles and reports, and obtain professional and

governmental reports. You have to do a literature review anyway, so this is time well spent. A reference

librarian in the Cal Poly Pomona library can assist you in conducting literature reviews. Note that many

useful government sources, reports, and data sets may be harder to find and not necessarily available in

the library. That might require web searches and cold-calling public officials in agencies that have

commissioned those reports.

Writing is also an essential tool for exploring topics. Sometimes it is difficult to begin writing because you

don't know where to start. Initially, view writing as a process for exploring ideas rather than an activity that

produces a final product. Try writing a series of paragraphs describing a problem or question that interests

you and is relevant to planning. Write a series of these statement—at least ten. Picasso reworked

canvasses repeatedly, often destroying what appeared to be beautiful work. You should expect to spend

quite a bit of time and encounter dead-ends in finding a suitable and interesting topic.

The next step is to evaluate the list of potential topics you have generated. Among the criteria you may use

to select your topic are:

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

5

• your personal interest in the research question

• its relevance to planning research and practice;

• the availability of data or cases to study and your mastery of required methods; and

• your ability to complete the research in a reasonable amount of time.

4. Setting Up and Working With Your Committee

The thesis process involves establishing a committee of three members who guide you in your research

and evaluate your work.

3

Each committee member must sign the thesis form before the Graduate

Coordinator approves it. It is your responsibility to select the proper committee, which starts with a

chairperson who has expertise in your topic and availability to add you to their teaching responsibilities.

You should also be able to get along with and easily communicate with that person and make sure they

are available in your timeframe. Your other committee members should be interested in the basic

direction and methodology of your research. The chair may be able to suggest other appropriate

committee members; one outside member, from practice or other academic department, can serve with

the approval of the Graduate Coordinator.

It is advisable to approach potential committee members before you enroll in URP 6960 in Spring

semester. That way, you will be able to quickly proceed once you enroll. You should submit the thesis

form, signed by each committee member, to the graduate adviser by the third week of the semester in

which you enroll in URP 6960.

Plan to meet with your chair at least once every two weeks; a once-a-week check-in is advisable. This

gives your chair a chance to help you make key decisions in your work. If you don't let your chair know the

status of your efforts you could make decisions that cause problems later on. Frequent meetings also

offer a structure that makes it easier to set aside time for the thesis and keeps the project “top of mind”

for the chair. It is easy to defer work on the thesis as other pressures assert themselves. A first task is to

develop a schedule listing key tasks, dates for completion, and submittals to your chair and committee.

Seek your chair’s advice on all the steps in the process—formulating problems and/or hypotheses,

designing the methodology, collecting, and analyzing data, and forming conclusions. The closer and more

regularly you work with your chair, the less likely you will face major revisions or delays in the end.

You likely will not work as closely with your other committee members as you do with the chair. However,

they should review your problem/hypothesis statement(s), methodology, data sources, and preliminary

conclusions. If they do not review your progress, questions could emerge at your defense that could have

been addressed earlier. A useful initial tool for communicating with your committee members is to

develop a short statement that summarizes the research hypotheses, the relevance of the topic, the

methodology, and an outline of the chapters. Regularly update this summary as you undertake your

research.

3

Your committee may also be composed of two department faculty members and an approved planning practitioner or

expert in your field. That person should be committed to spending the time to review draft work, attend your defense, and

review and approve the final document. Check with the Graduate Coordinator regarding the availability of tenure track

and lecturers to serve as chair.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

6

5. Sample Schedule

The following identifies a typical schedule for a student completing the degree in two years. Thesis is part

of the Planning and Public Policy track. See the URP Graduate Guide for further details.

Year 1 Spring semester: Complete URP 5210/L. This methods course will help you understand

research design. Also, identify research topics, potential committee members, and do

some background research. Take electives that provide knowledge and skills in your

prospective thesis topics (this could lead you to take a subject area elective early).

Summer break. Prepare to hit the ground running in year two by working on

literature review, methodology, and investigations of the availability of data.

Year 2 Fall semester: Enroll in URP 5230/L and URP 6902;

Spring: Enroll in URP 6960 with your chair. The Graduate Guide provides more information

on deadlines.

Some students take more than two years to complete the program and take advantage of options about

how to sequence the effort. One path is to follow the Year 1 and 2 sequence recommendations, except

enroll in 6960 the year you intend to graduate, but many alternatives are available. The advantage of

extending the thesis beyond the two-year program is time availability and focus. The disadvantage is the

challenge of staying on task without the support provided by fellow students and the classroom

environment.

6. Processes for Selecting Research Topics

One way to get started is to identify general hypotheses or problem statements for your research. In

quantitative methods, the term hypothesis has a specific meaning that you will address in your methods

classes. For this document, I use hypothesis to refer to an a priori statement about a relationship. For

example, you may define a general research hypothesis as follows:

• The quality of sea level rise adaptation plans is positively related to exposure to risk and

community affluence in local jurisdictions; or

• Housing development in an industrial zone reduces the economic performance of the

industrial district because resident complaints about impacts lead to operational restrictions;

or

• Rent control program ‘x’ has the effect of reducing housing construction, leading to higher housing

costs for non-rent controlled units.

The research may also be designed around a question. Here are some example questions, paraphrased

from a recent issue of the Journal of Planning Education and Research

• Does living in a neighborhood with high-quality public transit influence travel behavior later in life,

even if you move to a neighborhood with worse transit service? DOI: 10.1177/0739456X1795744

• Do parking maximums deter housing development? DOI:10.1177/0739456X16688768

• To what extent to form-based codes differ from conventional zoning in integrating sustainable

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

7

design principles? DOI: 10.1177/0739456X17692653

• Can “cleaned and greened” lots take on the role of public greenspace? DOI:

10.1177/0739456X16688766

The key to these statements is that they contain an initial assessment of a research question or a focused

question. To say you will study the rational comprehensive method or study the effect of parking

subsidies on travel behavior is not enough. Based on your initial research, you might state the expected

outcome and then test whether it is true. This enables you to be much more focused. If the evidence

doesn't support your initial hypothesis, that is an important research finding in itself. The expectations

you form are based on knowledge of previous research as shown in the literature. For example, you may

expect that you will support or challenge commonly held knowledge in a subject area.

Research methodologies are reviewed in your research methods classes (URP 5210/L, URP 5230/L, and

URP 6920). They provide experience in formulating hypotheses, developing research designs, and

exploring various analytic techniques. For example, research could be cross-sectional (comparing different

places at the same point in time) or time series (examining trends over time).

Of course, research can be exploratory and descriptive, especially if there is not a well-established record

of previous research. These are research questions that start with “how does….?” or “what

influences…..”?

Good thesis topics tend to have the following characteristics: 1) articulate a concise hypothesis or

research question; 2) identify where the project fits within the literature; 3) establish relevance and

interest in the topic; 4) determine that needed data is available or can be obtained; and 5) articulate a

feasible methodology.

Note that investigators in projects that involve human subjects must obtain training and approval of a

research protocol from the Cal Poly Pomona Institutional Review Board (IRB)

https://www.cpp.edu/research/research-compliance/irb/about-us.shtml

7. Literature Review

The literature review provides many important functions. Broadly, it synthesizes previous knowledge about

the topic. Note that the emphasis is on synthesizing, considering all of the literature, and making sense of

what it means collectively. This is very different than an annotated bibliography, which lists and summarizes

individual works of relevant research. The research librarian, your advisor, readings from the syllabi of your

courses, and the reference section in recent seminal articles can help you assess the state of knowledge in

this area. The Journal of Planning Literature provides literature reviews on important topics in planning. If

there is one for your topic you are in luck. It also provides good examples of what a literature review does.

A component of the literature also relates to your methodology. In scanning the literature, you are not just

looking for the key findings about the topic but also the research methods that are used. You could decide

to replicate a study you found, following that methodology but using a new and better data set. Or you

could decide that a new approach is needed. For example, if all studies of a phenomenon have been

quantitative, you might determine that at qualitative approach is needed.

In some narrow or brand-new topics, the literature that directly applies to your thesis is sparse. In this case,

expand your search to look for literature on related problems in planning, or draw on findings in other

disciplines that can be reasonably related to your planning topic.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

8

8. Writing Quality

The thesis is likely to be the longest and most complex document you have written. Writing quality is

critical. The best analysis and insight won’t mean much if the reader is distracted by confusing logic,

grammatical errors, style errors, or inconsistency. Think about the flow of ideas, the logical sequence of

presentation, and put yourself in the reader’s shoes. Write for them.

Painstaking editing is boring but essential. Appendix A provide some tips for writing. Your advisor may have

their own tips so make sure you understand their writing requirements. My favorite technique is using the

“Read Aloud” function in Microsoft Word.

9. Methodologies

While it may seem that a particular topic naturally leads to a particular research methodology, a variety of

methodological approaches are usually available. As mentioned, a basic distinction is quantitative versus

qualitative approaches but many projects are mixed-methods (i.e., using both qualitative and quantitative

methods).

Quantitative approaches concern measuring a phenomenon or establishing relationships between

phenomena in numerical terms (generally a deductive approach). Qualitative approaches tend to focus on

questions that are poorly suited to numeric expression or for which little research record exists (generally

an inductive approach). The two approaches are related because qualitative approaches may provide the

basis for the later testing of quantitative variables or relationships.

The choice in methodological approach partially relates to the amount of apriori theory available in the

literature. If the literature identifies relationships between variables, quantitative analysis can test a

hypothesis regarding those relationships. If there is less known about the phenomenon, qualitative analysis

casts a broader net. For example, a grounded theory approach seeks to develop theory from the data,

rather than test a pre-defined theory.

A useful way to think of the methodology section is that it should be so clear that you could give it to

another researcher who could implement the research, knowing what to do and why it is justified.

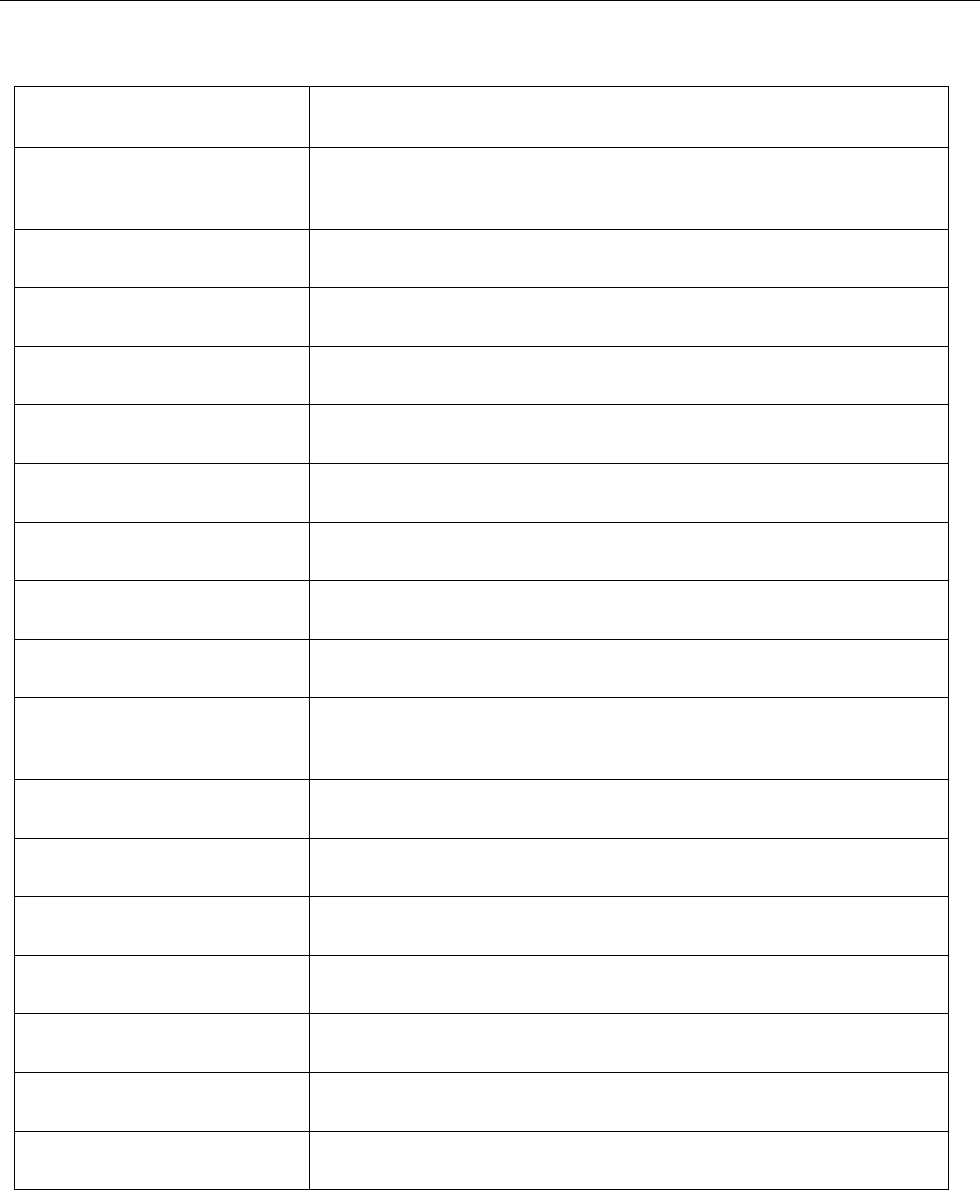

The following table provides examples of types of research methodologies, along with an example of each.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

9

Table 1. Research Types and Examples

Type

Example

Archival research

Research city archival records to assess the equity dimensions of

redevelopment agency “wind-down” in a city or a series of case

study cities

Attitudinal surveys

Conduct a stated preference survey asking respondents about their

likelihood to use a new transit service

Content analysis

Analyze Twitter posts to identify neighborhood attitudes regarding

gentrification

Design analysis

Apply a Lynch framework in a community-based participation

activity

Economic analysis

Conduct a cost effectiveness, cost/benefit, or fiscal impact analysis

of a solar panel incentive program

Ex-ante program evaluation

Evaluate the quality of alternative evacuation strategies for a fire-

prone community in a series of plans

Experiment

Organize, implement, document, and evaluate a tactical urbanism

intervention

Ex-post program evaluation

Conduct an after-the-fact assessment of the rail transit ridership

performance of a rail transit line

Focus groups

Identify students’ perspectives regarding elements of commuting

stress or stigma associated with public transit use

Interviews

Interview stakeholders about their perceptions of community

history, existing conditions, expectations for the future, or processes

for a land use controversy.

Oral histories

Interview long-time residents about their understanding of the

impact of “sundown” towns on inequality.

Participant observation

Volunteer at a “refilling station” to learn customers perceptions and

behaviors regarding reducing packaging in their consumption

Secondary research

Conduct a chronological analysis of the planning literature regarding

how the term equity is defined and used

Simulation models

Develop a simulation model of the equity implications of priced

residential parking permits

Statistical analysis

Conduct a multiple regression of the predictors of bikeshare use

levels

Statistical modeling

Develop a model to predict housing supply responses to mandatory

affordable housing requirements

Spatial modeling

Analyze the spatial determinants of bike or pedestrian crashes

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

10

10. Appendix Material

Appendix A provides technical writing tips and advice.

Appendices B – D provide worksheets and prompts used in URP 6902 to explore thesis topics. While it is

possible to possess a focused topic at the beginning, that is rare. Usually, there is an iterative process of

developing many alternative topics and preliminary methods. It may feel like you are spinning your wheels

at the beginning, but the time spent clarifying your topic and approach is paid off with an ability to proceed

in a timely manner. Use these worksheets in consultation with your thesis committee chair. Each one may

have a different approach.

Appendix E provides an annotated guide to internet resources that may be useful in completing your

thesis. The list was compiled from suggestions by URP faculty members.

Appendix F provides commentaries from MURP students who have recently completed their thesis. They

provide tips on the process.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

11

Appendix A: Technical Writing Tips and Requirements

Develop an ability to step back from your writing and imagine how a different person, seeing it for the first

time, would understand it. Put yourself in their shoes. Since they do not know what you know, make it easy

for them to understand your analysis. Seek to be helpful in their process of understanding - imagine how the

information unfolds in another person’s head. Write to make this process easier—what the reader needs to

know first, what second, etc. This requires that you step back from the process you used to reach your

conclusions.

The best writing is invisible – the reader is busy contemplating the ideas and the argument and is hardly

aware of a writing style. Bad writing draws attention to itself either through obvious errors or by being hard

to understand, or both.

Use words precisely – avoid sweeping generalizations that might be true in some cases and not true in

others. You don’t want to undermine your work by overstating something to an expert audience.

Carefully define your terms. Inadvertently using an extra adverb could imply a different research approach.

For example, there is a difference between descriptive analysis (understanding what is happening) and

prescriptive analysis (determining what should happen). An example of precision in word use for descriptive

analysis is using the term catalyst (meaning looking for causes of what happened) versus impacts (meaning

measuring the consequences of what happened).

Quantitative information is often usefully expressed in tables and figures. Think about what information is

essential to communicate your findings and provide that in a clear way. In some theses, the real story is in

the table and figures, with the text guiding the reader through and providing expansion and clarification. Do

not just dump the tables and figures on the reader hoping they will figure out what they mean. Explain to

the reader what each table means. Never put the tables and figures at the end, expecting the reader to flip

back and forth as they are reading it. Integrate tables and figures in the body of the report.

Good writing requires many, many edits – no one gets it right on the first draft. The payoff of editing is that

you more carefully consider your conclusions and that they are fairly considered by those who read your

work. The alternative is that your thoughts and ideas get rejected, even if they are good, because the writing

conveys sloppiness, a lack of commitment, or a confused mind. A very useful tool for editing is features in

word processing programs that will read you writing aloud. This will help you catch many errors because you

hear it instead of reading it. Our mind tends to jump past errors when we read things we have ourselves

written.

I prefer that you write in the present tense rather than the future (or past) tense, e.g., “This report studies

_______” versus “This report will study _______”. As you are writing, unwritten chapters are in the future to

you but the reader doesn’t experience it that way. They read in their present.

Help can come from the University Writing Center https://www.cpp.edu/lrc/our-team/writing-center.shtml

and your fellow students, friends, etc.

Ideas for Tables and Figures

• Each table or figure must have a Table # and title listed above or below it (e.g., Table 1. Mode Split

Percentage for Workers). Each table or figure is referred to in the text before it appears (e.g., “Table

1 shows that the majority of commuters drive alone…”).

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

12

• Do not cut and paste tables and figures from the internet. Create your own table or figure, focused

on what you need to communicate using Excel or a similar program. Provide a citation under the

table of figure. If you have created a table of figure based on someone else’s data, say: Source:

author compilation based on _______.

• Both axes on a table or figure must be labeled. Don’t allow Excel to put a “series 1” legend box when

there is no series.

• Use a consistent font and font size in tables and figures.

Citations

• Follow the citation style in the Journal of the American Planning Association or whatever system you

and your advisor agree upon.

• For example, in APA Style, if you are paraphrasing someone else’s idea, cite it in the text (Nelson

2010), with a full citation appearing at the end of the document. If you are using someone else’s

exact words, put the quote in “ ” and cite as (Nelson 2010, 32).

• Internet citations must include the URL and depending on the citations system employed, the date

accessed.

Writing style

• Do not use the first person, e.g., “you”

• Do not use contractions

• i.e., = “that is”, e.g., = “for example”

• If a number is less than ten, spell it out; if more than ten, display numerically

• Round off numbers in relationship to the level of precision required, e.g., don’t say a community is

14.14% Hispanic – use 14% or 14.1%

• Capitalization – if you are referring to a specific thing, capitalize; otherwise use lower case. Do not

capitalize unless a formal name.

• Limit paragraph length. Avoid run-on paragraphs.

• Vary sentence structure, e.g., don’t start a sequence of sentences with “The park is….” Vary

sentence length as well.

• Acronyms – if you refer to SCAG, the first time it is mentioned, write out Southern California

Association of Governments (SCAG) and then you can use SCAG thereafter.

• If a paragraph has a long list of things, consider using an introductory sentence followed by a

bulleted list.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

13

Appendix B – Worksheet for Exploring a Possible Topic

1) What is the general problem that motivates the research? In what subfield of planning do you locate it?

2) What evidence is there that others agree this is a problem? (literature, scientific evidence, public action,

news reports, etc.)

3) In one sentence, what is a tentative research question, problem, or hypothesis?

4) What disciplinary approach informs the methodology?

5) What is the unit of analysis? (e.g., case study (single or multiple), comparative analysis, convenience

sample, or statistical sample (and at what scale)?

6) What is the prospective methodology?

7) What is the data collection strategy? (secondary, primary; in-hand or needs to be obtained?)

8) What analytic capability is required to conduct the analysis? Do you possess it? If not, how will you

acquire it?

9) Does the project involve human subjects and therefore require IRB human subjects review?

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

14

Appendix C - Scripts for Developing Research Purpose Statements

This appendix includes scripts for focusing and explaining research purpose statements. Three scripts are

provided for quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods (the mixed-method example is convergent method).

These are drawn from the textbook for URP 6902, Creswell and Creswell’s Qualitative, Quantitative and

Mixed Methods Approaches. Taking inspiration from that approach, two other scripts are presented for ex

ante policy analysis, and ex post policy analysis. These are not all the options – mixed-methods research can

also include explanatory sequential and exploratory sequential methods (Creswell 2018, 127). Note that

other types of research may require a custom script, such as simulation models or descriptive quantitative

methods. Work with your advisor on an appropriate script.

Script for writing a quantitative research proposal:

The purpose of this ___________________ (experiment? survey?) study is to test the theory of

_________________ (theory name) that _______________ (compares? relates?) the _______________

(independent variable) to ____________________ (dependent variable), controlling for (control variables)

for (participants) at ______________ (the research site). The independent variable(s) _________________ is

defined as (provide a definition). The dependent variable(s) is defined as _______________ (provide a

definition), and the control and intervening variable(s), _________________, (identify the control and

intervening variables) is defined as _________________ (provide a definition).

Script for writing a qualitative research proposal

The purpose of this _____________________ (strategy of inquiry, such as ethnography, case study, or other

type) study is to ______________________ (understand? explore? develop? discover?) the ______________

(central phenomenon being studied) for _________________(the participants, such as the individual, groups,

organization) at ______________ (research site). At this stage in the research, the ____________________

(central phenomenon being studied) is generally defined as ___________________ (provide a general

definition).

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

15

Script for writing a mixed-methods evaluation research proposal (convergent method)

This mixed methods study addresses ____________(overall content aim). It used a convergent mixed-

methods design of collecting and analyzing qualitative and quantitative data in parallel and then merging the

results. In this study, __________ (quantitative data) is used to test the theory of __________(the theory)

that predicts that _________ (independent variables) _________ (positively, negatively) influences the

__________(dependent variable) for _________ (participants) at ___________ (the site). The ____________

(type of qualitative data) explores the ________ (central phenomenon) for ___________(participants) at

___________ (the site). The reason for collecting both quantitative and qualitative data is to ____________

(the mixed method reason).

Script for writing an ex-post evaluation research proposal (policy analysis)

The purpose of this evaluation study is to understand the efficacy of _______________________(plan,

design, policy, program, project, implementation mechanism) implemented at ______________ (name of

agency adopting, and date adopted). The evaluation assumes that the stakeholder perspective for the

evaluation is ____________________ (implementing agency, a defined conception of the public interest, or

stakeholder group). The evaluation is ______________________(single objective, multiple objective) and

_______________________________ (quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method). Results are compared to

___________________________________________ (original project objectives, best-practice standards,

combination, other).

Script for writing an ex-ante (anticipatory) evaluation research proposal (policy analysis)

The purpose of this evaluation study is to generate and analyze alternatives and recommend a

_____________________________(plan, design, policy, regulation, program, project, implementation

mechanism). The project is _____________________ (hypothetical, under consideration, already decided). It

is being considered by ______________ (name of agency adopting, if appropriate). The evaluation assumes

that the stakeholder perspective for the evaluation is ____________________ (implementing agency, a

defined concept of the public interest, or stakeholder group). The evaluation is

______________________(single objective, multiple objective) and _________________________

(quantitative, qualitative, mixed method). Alternatives are compared to evaluation criteria of

___________________________________________ (effectiveness, cost, administrative feasibility, equity,

political feasibility, etc.) leading to a recommendation.

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

16

Appendix D – Prompts for Developing a Detailed Thesis Proposal

Tentative thesis title ____________________________________________________________

Topic – indicate the topic area, its relevance to urban and regional planning research, and drill down to the

more specific element of interest. Why is it important? Support your claim with the literature.

Problem – explain two dimensions – 1) the societal or planning problem (e.g., arbitrary decisions are made

when appropriate local threshold standards are not adopted for CEQA documents), and 2) the lack of

knowledge problem (e.g., there is no systematic comparison of CEQA findings among jurisdictions with and

without threshold standards). Support this section with the literature.

Purpose – explain how the research project addresses the problem(s). Articulate an Appendix C purpose

statement script with advice from your thesis chair.

Research questions or hypotheses – state research questions for qualitative research, hypotheses for

quantitative research, or hybrids for mixed-methods. For ex ante policy analysis, state the focus of

evaluation (e.g., improving alternatives, criteria, or weighing of criteria). For ex post policy analysis, state the

expectation of the outcome that will be tested.

Proposed information sources – indicate the type of data to be used (e.g., qualitative, quantitative,

combination), proposed sources, and assess data quality and availability. Provide a statement on the level of

risk associated with successfully obtaining the data. If the risk of not obtaining is significant, offer a backup

strategy. Support this section with the literature and links to data sources.

Proposed methodology – explain the methodology, such as qualitative, quantitative, mixed-method, or

policy analysis. Propose the analysis tools to be used and demonstrate competency in those tools. Provide a

justification for the study area, cases, or study subjects proposed, if applicable. Support the methodology

with the literature, i.e., explaining how your project meets a need (new approach, replicating an approach

with a different case, better data, or better analytic tool).

Project planning – provide a timeline for the research, including tasks completed during Fall semester and

completion in Spring or a subsequent semester. Provide a critical path analysis for completion.

Institutional Review Board – discuss applicability and status of IRB submission.

Potential chair and committee members

Chair: ______________________________________

2

nd

member: _________________________________

3

rd

member: _________________________________

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

17

Appendix E: Annotated Guide to Resources

Resources on the Web

Advice from JAPA Editor Ann Forsyth (a tip from Alvaro Huerta)…

Resolving to Graduate on Time: Troubleshooting Your Urban Planning Exit Project or Thesis Advice

https://www.planetizen.com/node/29121

Getting Started on an Exit Project or Thesis in Planning

https://www.planetizen.com/node/29520

Common Problems with Proposals for the Exit Project or Thesis in Planning

https://www.planetizen.com/node/29949

Managing Up: Your Thesis or Project Committee as a Trial Run for the World of Work in Planning

https://www.planetizen.com/node/30572

Making Sense of Information: Using Sources in Planning School

https://www.planetizen.com/node/40408

Skills in Planning: Writing Literature Reviews

https://www.planetizen.com/node/36600

Finishing the Exit Project in Planning

https://www.planetizen.com/node/30995

Comprehensive Guide Used at Harvard - A Guide for Students Preparing Written Theses, Research Papers,

or Planning Projects

http://annforsyth.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ForsythEssentialInfo-Sept-2016.pdf

Advice from former JAPA Editor Sandi Rosenbloom…

Author Guidelines for JAPA Manuscripts is guidance for authors submitting articles to the Journal of the

American Planning Association. While a journal article is different than a thesis, the guide contains good

information on the generic chapter headings, e.g., what should be in the Introduction, and the purpose and

relationship of introduction, literature review, methodology, substantive findings, and conclusion. Note that

your thesis chapters will be longer than the word length guidance in the Guidelines. Regarding format, you

may choose to follow a different style, but the one used by JAPA is fine. The document is available at:

https://www.tandf.co.uk//journals/authors/style/rjpa-guidelines.pdf

Books

Creswell and Creswell’s Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. This is the text that

is currently used in URP 6902.

Giddens’ Sociology 6

th

Edition. Chapter 2 addresses different research methods which you may find

useful. It is available online. (tip from Brian Garcia)

Yin’s Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Yin explains different methods that could be used in

case studies, so it is also an overview of research methods as well as a case study guide. I think the most

valuable part I have found from Yin’s book is that he discusses when to use what type of method to

answer what kind of question. (tip from Brian Garcia)

Lamott’s Bird by Bird, it is free online I recommend the “Shitty First Drafts” chapter to get started. (tip

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

18

from Brian Garcia)

http://richardcolby.net/writ2000/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Bird-by-Bird-Anne-Lamott.pdf

Barbato & Furlich, Writing for a Good Cause: The Complete Guide to Crafting Proposals and other

Persuasive Pieces for Nonprofits. (tip from Brian Garcia)

Field, A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. The best guide for statistics I have found. (tip

from Brian Garcia)

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

19

Appendix F: Tips on Thesis Process from MURP Alumni

The following commentaries discuss the thesis process from the point of view of four MURP

alumni who recently completed their thesis.

Jin Eo (2018)

Thesis Title: Analyzing How Bus Ridership is Influenced by Physical Environments, Crime, and

Collision Adjacent to Bus Stops

My thesis journey experience was challenging, but the outcome outweighed any stress I

developed in the process. The process was about two quarters long (CPP was in the quarter

system then) and the topic I chose was about how ridership is affected by the built environment

of bus stations. I wanted to focus on quantitative analysis, so I chose Dr. Do Kim as my advisor.

What was extremely helpful was that my advisor was there for me every step of the way. We

had weekly meetings in person and talk about my progress and any challenges that I was facing.

He offered resources and helped me think more critically, which is a skill that planners need to

have in the real-world.

Based on my experiences, here are some tips that I have for current graduate students who are

about to embark on their own thesis journey:

1. Think of a topic where you don’t have to figure out ways to control variables.

2. Choose an advisor that aligns with your interest and is available for frequent

communication.

3. Your thesis journey and outcome will be more valuable if you select a thesis

committee whose members will challenge your research so that you can improve your

skills and critical thinking for the real world. In other words, don’t choose your co-worker

as part of your thesis committee because you know they’ll give you a pass without

challenging you.

I highly recommend taking on the thesis route in your graduate school experience because it will

open many doors for you. You can use your thesis as part of your portfolio when you interview

for a job at a private sector firm or government agency.

The skills I developed in my thesis proved to be useful in my current work. I got to work on GIS

skills such as zonal statistics and various geoprocessing tools. Most importantly, I learned good

time management skills statistically summarizing large amounts of data in a short period of time.

These skills are important in some transportation consultant roles.

Clarissa Manges (2020)

Thesis Title: Understanding Public Transportation Accessibility for Adults with Autism Spectrum

Disorders: A Six Feelings Approach

From the start of my time in the MURP program, I knew I wanted to write a thesis. At first, I was

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

20

only interested because of the associations with “hard work”, “research ability”, and “original

contributions” that the word “thesis” suggests. Later, I also became interested because of its

practicality; as a person that highly values independence and stability, a thesis made sense

because it allowed me near-complete control of my own work (this could be especially helpful

for students that need flexible scheduling/pacing). In contrast, my classmates doing projects had

to arrange their deadlines and scope of work around the client’s interests, and a few had to start

from scratch after their client backed out.

As mentioned above, the thesis option might be best for those that need to finish the program

outside the traditional 2-year timeframe. However, as someone that did finish within that

timeframe, the best advice I can give is this: START EARLY. Specifically, it would be best to start

the summer before your thesis prep class (URP 6902). I started then, for two reasons. For one, it

was the point when I had been in the program long enough to realize my passions in the

planning field and long enough to realize my ideal topic after a presentation at the April 2019

National APA Conference (NOTE: APA events are an excellent source for inspiration because they

discuss the most timely issues in planning). For another, it was also the point when my research

methods class (URP 5210) was still fresh in my mind and I could use the elements we had

discussed (i.e., unit of analysis, exploratory vs. explanatory research, quantitative vs. qualitative

methodologies) to sculpt the foundation for my study. By the end of the summer, I had found

most of the sources for my literature review, settled on a few methodology options, and formed

a solid research question.

Of course, I still had a number of setbacks while completing my thesis. I needed time to decide

on my precise methodology, I turned in my IRB protocol later than I should have, I got fewer

snowball-sampled respondents than desired for my survey (a lack of incentives and the all-

online format were the biggest culprits), and I took much longer to complete my analysis than

anticipated. Externally, the 2020 global pandemic required a period of academic and emotional

transition, and then a family member had a major health crisis the week before my defense.

What kept me on track, however, was using the foundation I had built both to help me adjust

my plans and to identify the tasks I could work on during interim periods. For example, I read

other MURP theses for inspiration and wrote my Introduction and Literature Review chapters

while waiting for IRB approval to collect data.

Ultimately, I had a successful defense and a positive experience writing the thesis. I felt

accomplished for completing such a large undertaking and for teaching my professors about a

topic that was passionate and personal to me. I learned so much from the thesis journey too-

about how to do academic research, about how to engage hard-to-reach populations like the

one I worked with, about how to manage large projects, etc. Looking back, I know that choosing

a thesis, and starting early, was the right choice.

Eve Moir (2016)

Thesis Title: Sea-Level Rise Adaptation Planning : An Analysis of California Coastal Cities

My Master’s thesis allowed me to explore a subject that is related to my major and focus while

pushing the boundaries of the curriculum. It provided the freedom to research a specific subject

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

21

and embark on a research exercise that I would not have had the freedom to do otherwise. It

also allowed me to sharpen my research and writing skills. The one-on-one work with my thesis

committee also provided invaluable lessons.

I completed my thesis in two consecutive quarters by creating a thorough workplan and outline

with Professors Willson, Mitchell, and Huerta. One piece of advice that was drilled into my work

at that time was to narrow down my subject. Tending to think broad and big picture did not

serve the thesis work well. Consistent and thorough reviews throughout the writing and

research process helped identify issues and keep the process on track.

The process and lessons learned have been used throughout my career thus far. As a Manager

at LA Metro, our transit corridor projects require extensive analyses. I take the workplan and

outline approach each time I embark on a specific writing process. Most recently, I wrote my

first Title VI Equity Analysis for a corridor project, serving as the department example.

Alex Okashita (2018)

Thesis Title: Market-rate Residential Parking Permit Fees: An Exploration Of Incidence On Low-

income Households In Los Angeles, California

I chose to do a thesis because I wanted something tangible to take with me after graduation. I

also wanted to explore a topic interesting to me, have something to show to employers, and to

keep an open door in case I wanted to pursue doctoral studies.

One of the larger fears of doing a thesis is the chance that you won’t finish in time. There are

three things you can do to mitigate this scenario. First, choose an advisor and committee that

has proven their availability to students during your program. Second, choose a dataset that is

manageable to collect or discover. Creating data from scratch and choosing data that is reliant

on factors outside of your control (people to interview, travel, events, weather, etc.) means that

you are no longer in control of your thesis timeline. Third, hone in on the same paper topic

throughout your classes. You will complete the requirements for your courses and be writing

your literature review at the same time. If you have already completed most of your courses,

select a topic you have already explored. If your number one goal is to finish the thesis on time,

consider being flexible on certain aspects of your thesis to achieve these three points.

How to stay on track? When I started, I created a Gantt chart to schedule required tasks to finish

my thesis on time. Most of my work wasn’t actually complete until 1 to 2 weeks after the

deadline. Do not create deadlines on the absolute latest date a task needs completion. Consider

a buffer period for fixing mistakes, coordinating meetings with a busy advisor, and encountering

the chance you underestimated your workload. There can be revisions at any point of the thesis

process, up until the moment you submit your final draft to the librarian.

Once you have all the pieces to begin writing the bulk of your thesis, I recommend taking time

off from work to write uninterrupted. Before writing anything, learn the tools available to you

on your word processor or third party applications (e.g., Zotero). Having dynamic Figure/Table

Demystifying the Thesis: Guidelines for Starting and Finishing Your Thesis in Urban and Regional Planning

22

numbers and references can dramatically speed up the writing and revision process and reduce

human error.

What were the real-world takeaways? It was daunting at first to move up the student-teacher

participation level that started out from receiving information through lectures to contributing

knowledge from your research under guidance from your advisor. However, this is typically how

participation and collaboration works in the industry. Thus, the thesis process gave me valuable

real-world work experience in self-discipline, knowing when to ask for help, and managing

expectations with your advisor.

After completing the thesis, my advisor and I wanted to disseminate our findings to a broader

audience. We decided to submit the findings to the Transportation Research Record journal by

condensing and refining the thesis into a journal format. The article was soon accepted and

published after peer review with an opportunity to present the findings at the Transportation

Research Board annual conference in Washington, DC. Eventually, I decided to pursue a Ph.D.,

and I cited this experience in my applications. I was told that the experience I gained from

attempting a journal article submission was instrumental in securing interviews and ultimately,

acceptance into a Ph.D. program.

Okashita, A., & Willson, R. (2019). Impact of Market-Rate Residential Parking Permit Fees on

Low-Income Households. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation

Research Board. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198119878381