1

District Freight Plan Update

November 1, 2022

Resubmitted March 17, 2023

District Department of Transportation

SENT ELECTRONICALLY

District of Columbia Division 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

East Building (E61-205)

Washington, DC 20590

(202) 493-7020 – Office

www.fhwa.dot.gov/dcdiv/

In Reply To: HDA-DC

Mr. Everett Lott

Director, District Department of Transportation

250 M Street, SE, Suite 900

Washington, DC 20003

Subject: District of Columbia’s Updated State Freight Plan – BIL/IIJA Compliant

Dear Mr. Lott:

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) District of Columbia Division Office (Division

Office) has reviewed the District Department of Transportation titled District Freight Plan Update

(revised) on March 17, 2023 and received by the Division Office on March 19, 2023.

The Division Office finds that the Plan contains all elements required by 49 U.S.C. § 70202. The State

has, therefore, met the prerequisite in 23 U.S.C. § 167(h)(4) that it develops a State Freight Plan in

accordance with 49 U.S.C. § 70202 before it may obligate funds apportioned to the State under 23

U.S.C. § 104(b)(5). The State may now obligate such funds for projects that meet all National

Highway Freight Program (“NHFP”) eligibility requirements described in 23 U.S.C. § 167, and all

other applicable Federal requirements.

Please be advised that the Division Office’s finding that the Plan satisfies the requirements of 49 U.S.C.

§ 70202 and 23 U.S.C. § 167(h)(4) is not a determination that the projects listed in the freight

investment plan component of the Plan required by 49 U.S.C. § 70202(c)(2) meet all other NHFP

eligibility requirements set forth in 23 U.S.C. § 167, or any other applicable Federal requirement.

If you have any questions regarding NHFP eligibility requirements, please contact

[email protected] or 202 493-7031.

Sincerely,

Joseph C. Lawson

Division Administrator

JOSEPH C

LAWSON

Digitally signed by

JOSEPH C LAWSON

Date: 2023.06.12

10:16:26 -04'00'

June 12, 2023

2

Table of Contents

1.0 Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 7

2.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 15

3.0 Strategic Goals & Objectives .................................................................................. 17

1.1. Federal Requirements .......................................................................................................... 17

1.2. State Strategic Vision, Goals & Objectives ....................................................................... 18

1.2.1. Vision ....................................................................................................................................... 19

1.2.2. Goal 1: Mobility ....................................................................................................................... 19

1.2.3. Goal 2: Sustainability ............................................................................................................. 19

1.2.4. Goal 3: Management and Operations (State of Good Repair) ....................................... 20

1.2.5. Goal 4: Safety ......................................................................................................................... 21

1.2.6. Goal 5: Security ...................................................................................................................... 21

1.2.7. Goal 6: Equity ......................................................................................................................... 21

4.0 Freight Infrastructure ........................................................................................... 22

1.0. Highway .................................................................................................................................. 22

1.0.0. Pavement Type & Condition ................................................................................................ 25

1.0.1. Bridge Characteristics & Condition ..................................................................................... 26

1.0.2. Loading Zones ........................................................................................................................ 26

1.1. Rail .......................................................................................................................................... 27

1.2. Air ............................................................................................................................................ 28

1.3. Maritime / River ..................................................................................................................... 30

1.0. Commercial Ports ................................................................................................................. 31

1.1. Truck Parking Facilities and Safety .................................................................................... 33

1.2. Critical Urban Freight Corridors (CUFC) ........................................................................... 34

1.2.1. CUFC Identification Process ................................................................................................ 36

1.2.2. Washington, DC Critical Urban Freight Corridors ............................................................. 37

5.0 Freight Demand & Economy ................................................................................... 42

3

1.3. Role of Freight in the District Economy ............................................................................. 42

1.4. Freight Generators ................................................................................................................ 44

1.5. Economic Forecasts ............................................................................................................. 50

1.6. Supply Chain Cargo Flows .................................................................................................. 50

1.6.1. Cargo Flows ............................................................................................................................ 50

2.2.1 Trade type and directionality .............................................................................................50

1.6.2. Freight Modes ......................................................................................................................... 52

1.6.3. Domestic and Foreign Trading Partners ............................................................................ 54

1.6.4. Commodity type ..................................................................................................................... 56

1.6.5. Key industries ......................................................................................................................... 61

1.7. Supply Chain Considerations .............................................................................................. 61

1.8. E-Commerce and Related Planning Considerations....................................................... 63

1.9. Military Freight Considerations ........................................................................................... 67

1.9.1. Strategic Defense Networks ................................................................................................. 67

1.9.2. Projects Overlapping the Strategic Defense Networks .................................................... 70

1.9.3. Considerations of Military Freight Movements .................................................................. 72

6.0 Freight System Performance .................................................................................. 73

1.10. Multistate Freight Compacts ............................................................................................... 73

1.11. Multistate Metropolitan Planning Organization Coordination ......................................... 74

1.12. Freight Resilience, Environmental, and Equity Considerations..................................... 74

1.13. Freight Bottleneck Inventory and Mitigations ................................................................... 79

1.13.1. Freight Bottleneck Inventory ............................................................................................ 79

1.14. Freight Bottleneck Mitigations ............................................................................................. 81

1.15. Freight-Related Congestion and Mitigations .................................................................... 82

1.16. Consideration of Heavy Vehicle Impacts & Mitigations .................................................. 83

1.17. Innovative Technology and Intelligent Transportation Systems Considerations ........ 84

1.18. Freight Needs & Issues ........................................................................................................ 85

4

1.18.1. Competition for Space ....................................................................................................... 85

1.18.2. Truck Routes, Restrictions & Enforcement .................................................................... 86

1.18.3. Congestion & Parking Constraints .................................................................................. 86

1.18.4. Bridge Network on Truck Routes .................................................................................... 88

1.18.5. Vertical Clearance Restrictions ........................................................................................ 89

1.18.6. Pavement Condition .......................................................................................................... 89

1.18.7. Geometric Design .............................................................................................................. 90

7.0 Freight Advisory Committee Input ......................................................................... 91

8.0 Recommendations, Funding, & Investment Plan ................................................. 92

1.19. Freight Projects & Recommendations ............................................................................... 92

1.20. Freight Funding Sources ..................................................................................................... 97

1.20.1. Current District DOT Federal Funding Allocation ......................................................... 97

1.21. Freight Investment Plan ....................................................................................................... 97

9.0 Freight Plan Implementation & Performance Measures ................................... 103

1.22. National Freight Planning Goals ....................................................................................... 104

1.23. Recommended DDOT Performance Measures ............................................................. 106

1.23.1. Sustainability Goal ........................................................................................................... 106

1.23.2. Mobility Goal ..................................................................................................................... 107

1.23.3. Safety Goal ....................................................................................................................... 109

1.23.4. Security Goal .................................................................................................................... 110

1.23.5. Management & Operations Goal ................................................................................... 110

1.23.0. Equity Goal ........................................................................................................................ 111

1.23.1. Performance Measures Summary ................................................................................ 112

5

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 I Required State Freight Plan Elements and Location in District Freight Plan Interim Update........... 17

Figure 16 I Map of general location of S Street SW Dock ................................................................................. 31

Figure 30 | Washington, DC Critical Urban Freight Corridors ........................................................................... 38

Figure 31 | Washington, DC Critical Urban Freight Corridors in Downtown DC ............................................... 39

Figure 32 | Critical Urban Freight Corridor Descriptions ................................................................................... 40

Figure 2 I 2022 Tonnage for Shipments Within, From, and To the District of Columbia by Trade Type and

Mode (in kilotons)....................................................................................................................................... 51

Figure 3 I 2022 Value for Shipments Within, From, and To the District of Columbia by Trade Type and Mode

(in million U.S. Dollars) .............................................................................................................................. 52

Figure 4 I 2022 Freight Modes Within, From, and To the District of Columbia by Shipment Tonnage (in

kilotons) ...................................................................................................................................................... 53

Figure 5 I 2022 Freight Modes Within, From, and To the District of Columbia by Shipment Value (in million

U.S. dollars) ............................................................................................................................................... 53

Figure 6 I Top 5 Domestic Trading Partners, Ranked by Kilotons .................................................................... 54

Figure 7 I Top 5 Domestic Trading Partners Ranked by Value (in million U.S. dollars) ................................... 54

Figure 8 I Foreign Trading Partners for District of Columbia (in kilotons) ......................................................... 55

Figure 9 I Foreign Trading Partners for District of Columbia (in million U.S. dollars) ....................................... 55

Figure 10 I Shipments Within District of Columbia - Tons by Commodity: 2022 .............................................. 56

Figure 11 I Shipments Within District of Columbia - Value by Commodity: 2022 ............................................. 57

Figure 12 I Shipments Inbound District of Columbia - Kilotons by Commodity: 2022....................................... 58

Figure 13 I Shipments Inbound District of Columbia - Value by Commodity: 2022 .......................................... 59

Figure 14 I Shipments Outbound District of Columbia - Kilotons by Commodity: 2022 .................................... 59

Figure 15 I Shipments Outbound District of Columbia - Value by Commodity: 2022 ....................................... 61

Figure 17 I Change in Online Retail Spending from October 2021 to October 2022 ........................................ 64

Figure 18 I Change in Online Spending at Restaurants and Bars from October 2021 to October 2022 .......... 65

Figure 19 I Military Installations within the District of Columbia ........................................................................ 67

Figure 20 I STRAHNET within the District of Columbia .................................................................................... 68

Figure 21 I STRAHNET and STRAHNET Connectors within the District of Columbia ..................................... 69

Figure 22 I STRACNET within the District of Columbia .................................................................................... 70

Figure 23 I Projects within DDOT’s FY 2023-2028 Budget Overlapping the Strategic Defense Networks ...... 71

Figure 16 I Map of general location of S Street SW Dock ................................................................................. 66

Figure 24 I Projected Future Sea Levels at National Mall/United States Capitol in Washington D.C .............. 75

Figure 25 I EV Charging Infrastructure .............................................................................................................. 78

Figure 26 I The Top 20 Roadways in the District with the Highest Total Delay in 2019 ................................... 80

Figure 27 | District of Columbia Apportionments under the National Freight Program FY 2023-2030 ............. 97

Figure 28 | District of Columbia Freight Investment Plan (2023-2030) Projects Funded by NHFP Funds ....... 98

Figure 29 | District of Columbia Freight Funding Summary ............................................................................ 101

Figure 33 | Alignment of National Goal Areas and National Performance Management Measures ............... 105

Figure 34 | Sustainability Performance Measures ........................................................................................... 107

Figure 35 | Mobility Performance Measures .................................................................................................... 107

6

Figure 36 | Safety Performance Measures ...................................................................................................... 109

Figure 37 | Enjoyable Spaces Performance Measures ................................................................................... 110

Figure 38 | Management and Operations Performance Measures ................................................................. 111

Figure 39 | Performance Measures Sums ....................................................................................................... 113

7

1.0 Executive Summary

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), passed on November 6, 2021, requires

each State receiving funding under the National Highway Freight Program to develop a

State Freight Plan that defines the immediate and long-range planning activities and

investments of the State with respect to freight, and adds several new required elements

that a State Freight Plan must include. This update serves as the guiding document for

freight in the District while a larger consultant-led state freight plan update is underway.

Launched December 2022, the consultant-led update will include more in-depth data

analysis and community outreach and will be submitted to FHWA in December 2023. In the

interim, this update includes all of the required elements of a state freight plan per IIJA.

Chapter 2 Highlights: Introduction

The District of Columbia (the District) is a dense urban environment with a diverse mixture

of land uses that place significant demand on the city’s transportation infrastructure. The

city’s role as a regional employment center creates a high volume of commuter traffic in

peak hours, while the consumer-driven economy generates significant demand for freight.

The District has experienced a substantial population increase and sustained economic

development over the past decade, generating a growing demand for freight activity. While

businesses continue to thrive, contributing greatly to the economic needs of the city, the

District’s overall population growth has caused an increase in demand for housing,

employment, and goods and services, all of which create increasing pressure on the city’s

transportation network.

Chapter 3 Highlights: Strategic Goals & Objectives

The strategic vision is of an efficient goods movement system that is sustainable, safe, and

secure. All projects will be reviewed and prioritized through an equity lens and will work to

eliminate or minimize negative impacts on historically burdened communities. Additionally,

the vision is of reliable freight operations to carry the goods that will enable the District’s

economy to continue to grow and the residents and public and private sector

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

8

establishments to thrive. The vision is comprised of six goals focused on improving

mobility, sustainability, management & operations, safety, security, and equity. The District

will strategically invest in technology to support the goals of this vision.

#

Required State Freight Plan Element

Plan Location

1

an identification of significant freight system trends, needs,

and issues with respect to the State

Chapter 5 (pp 42-62)

and

Chapter 6 (pp 85-90)

2

freight policies, strategies, and performance measures that

will guide the freight-related transportation investment

decisions

Chapter 3 (pp 17-21)

and Chapter 9 (pp

106-112)

3

When applicable, a listing of—

--multimodal critical rural freight facilities and corridors

designated within the State

--critical rural and urban freight corridors designated within

the State

Chapter 4 (p 34)

4

how the plan will help meet the national multimodal freight

policy goals and the national highway freight program goals

Chapter 9 (p 104)

5

description of how innovative technologies and operational

strategies that improve the safety and efficiency of freight

movement were considered

Chapter 6 (p 84)

6

where heavy vehicles (including mining, agricultural, energy

cargo or equipment, and timber vehicles) are projected to

substantially deteriorate roadway conditions, ways to

reduce or impede the deterioration

Chapter 6 (p 83)

7

An inventory of facilities with freight mobility issues, such as

bottlenecks, within the State, and for those facilities that are

State owned or operated, a description of the strategies the

State is employing to address those freight mobility issues

Chapter 6 (p 79)

8

consideration of any significant congestion or delay caused

by freight movements and any strategies to mitigate that

congestion or delay;

Chapter 6 (82)

9

a freight investment plan

Chapter 8 (p 97)

10

the most recent commercial motor vehicle parking facilities

assessment conducted by the State:

--- the capability of the State, together with the private

sector, to provide adequate parking facilities and rest

facilities for CMVs engaged in interstate transportation

---the volume of commercial motor vehicle traffic in the

State ---whether there are any areas with a shortage of

adequate CMV parking facilities, including an analysis of

the underlying causes

Chapter 4 (p 33)

9

11

the most recent supply chain cargo flows in the State,

expressed by mode of transportation

Chapter 5 (pp 50-61)

12

an inventory of commercial ports in the State

Chapter 4 (p 31)

13

consideration of the findings or recommendations made by

any multi-State freight compact to which the State is a party

under sec. 70204

Chapter 6 (p 73)

14

the impacts of e-commerce on freight infrastructure in the

State

Chapter 5 (p 63)

15

considerations of military freight

Chapter 5 (p 67)

16

Strategies and goals to decrease:

--the severity of impacts of extreme weather and natural

disasters on freight mobility;

--the impacts of freight movement on local air pollution;

--the impacts of freight movement on flooding and

stormwater runoff; and

--the impacts of freight movement on wildlife habitat loss; &

Chapter 6 (pp 74-79)

17

Consultation with the State freight advisory committee

Chapter 7 (p 91)

Chapter 4 Highlights: Freight Infrastructure

• Trucking accounts for almost all of the inbound and outbound freight shipments in

the District. Based on a recent DDOT transportation asset management analysis

1

,

91 percent of DDOT-owned National Highway System pavements were in good or

fair condition, 99 percent of DDOT-owned Interstate Pavements were in good or fair

condition, 90 percent of DDOT-owned Non-Interstate NHS Pavements were in good

or fair condition, and 82 percent of non-DDOT owned pavements were in good or

fair condition.

• The District has more than 600 commercial loading zones, each with signs that

specify days and hours of operation. These zones are short-term curbside metered

parking zones exclusively for commercial vehicles that provide local businesses a

designated space to receive deliveries when off-street options are not available.

• Approximately 44 million tons of cargo is shipped by rail that travels through, to or

from the District along 20 miles of active track. Rail traffic is nearly 100% “through”

with essentially no pickups or drop-offs in the District.

• While the DC region is currently served by three airports, Baltimore Washington

International (BWI), Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD), and Ronald

1

DDOT TAMP October 2022 Report

https://ddot.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ddot/TAMP_Master_SlideDeck_v3.pdf

10

Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA), only BWI and IAD play a substantial

role in the movement of cargo. BWI continues to serve domestic demand, while

IAD’s growth in air cargo is more in the international sector. Both markets are

forecast to grow through the year 2040.

• Although the District’s boundary encompasses two major rivers, neither is a

significant source of freight movements. The only dock located on District land that

serves as a commercial port is adjacent to the South Capitol Street Bridge on the

Anacostia River. DDOT has used this S Street SW dock to support the inspection,

maintenance, and construction of bridges. There is also a small U.S. government

maritime operation by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers along the Anacostia River,

which has been used to import gasoline and aggregate. If existing District maritime

facilities are not preserved, there could be negative environmental, safety, and cost

implications of diverting these heavy materials to trucks.

• DDOT estimates that truck traffic in the District on Interstate roads is roughly 4% of

AADT (Annual Average Daily Traffic) and is approximately 3% AADT on all other

District roadways. Between 2020 and 2022 there were 6,888 crashes involving

commercial vehicles in the District. These crashes resulted in 11 fatalities and over

1,000 injured persons. Of all crashes in those two years, 92 involved pedestrians

and 37 involved bicyclists. Half of all incidents were side swipes or rear end

collisions. DDOT understands that a lack of truck parking can cause fatigue-related

crashes. Since providing truck parking in the District is extremely challenging due to

our constrained right of way and dense development, DDOT is coordinating with

neighboring jurisdictions to identify regional truck parking facilities.

• The District National Highway Freight Network (NHFN) is comprised of Primary

Highway Freight System and Critical Urban Freight Corridor (CUFC) roadways. A

total of 74.98 miles of CUFC roadways are currently identified by DDOT for the

District. Since, under IIJA, the District of Columbia qualifies for up to 150 miles of

CUFCs, DDOT plans to identify additional roadway miles in the near future.

Chapter 5 Highlights: Freight Demand

• Goods movements into the District dwarf those traveling within or out of the District.

By weight and value, more freight comes into the District than leaves it.

11

• Freight traffic in the District is expected to grow by 74 percent from 2011 to 2040 in

terms of tons, and 159 percent from 2011 to 2040 in terms of value.

• 129,950 jobs directly or tangentially affected by truck represented 15.8 percent of

the 823,000 jobs in the District (in 2011).

• Wholesale Trade and Manufacturing were perhaps the most truck-integrated

industry. The Retail Trade and Construction sectors were also highly dependent on

truck transportation.

• The top five trading partners by cargo tonnage are the District’s close neighbors of

Maryland and Virginia within the Metropolitan Washington, D.C. Freight Analysis

Framework Zone, followed by Baltimore, the rest of Virginia, and the Virginia Beach

Norfolk metropolitan zone. The same pattern emerges when looking at the District’s

top five trading partners by cargo value.

• Foreign zones make up less than 2% of the District’s trade by tonnage. More than a

third of the District’s trade by tonnage is with Mexico and the Rest of the Americas

(not including Canada). Foreign zones also make up less than 2% of the District’s

trade by value, with the two biggest trading partners by value being the SW &

Central Asia zones.

• For commodities imported into the District by tonnage, nonmetal mineral products

and petroleum-based products make up nearly 40%, reflecting the construction and

energy needs of the region. By cargo value, however, electronics, pharmaceuticals,

miscellaneous manufactured products (such as cleaning tools, sports equipment,

jewelry, and toys), and motorized vehicles rise to prominence, reflecting its large

consumer market.

• In keeping with the District’s large consumer market, nearly 40% of the District’s

commodity exports by weight is comprised of waste / scrap. For outbound

commodities by value, pharmaceuticals and electronics make up nearly 40% of

District exports.

• Key industries within the region: construction and utilities, pharmaceuticals,

government, and a large consumer-based economy requiring goods and services.

• The increasing prominence of e-commerce has challenging impacts on freight

infrastructure and logistics. These deliveries require infrastructure such as

distribution centers and curb space or loading dock access to unload goods. This

poses challenges in the District because of the limited and highly contested curb

space. DDOT is exploring new strategies and policies to address these challenges.

12

• As for military freight considerations, DDOT has identified the Strategic Highway

Network (STRAHNET) and the Strategic Rail Corridor Network (STRACNET), any

DDOT related projects that might overlap those networks, and general military

freight considerations to incorporate into planning efforts.

Chapter 6 Highlights: Freight System Performance

• Coalitions that forge multi-state freight connections and contribute to planning and

operations management, to which the District of Columbia is a party, include: The

Eastern Transportation Coalition (TETC), M-495 Potomac River Commuter Fast

Ferry Project, and the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board

(TPB), the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the region.

• DDOT’s freight program expands on resilience, environmental, and equity

considerations already within District plans, such as MoveDC and Sustainable 2.0.

To prepare for climate change and transportation disruptions, the District is investing

in green infrastructure and projects that create network redundancy. To support the

District’s goal to be carbon neutral by 2050, DDOT is leading a delivery microhub

feasibility study, developing a delivery demand management program, and investing

in electric vehicle charging. To reduce wildlife impacts, commercial access to wildlife

habitats will continue to be restricted. Additionally, all DDOT freight projects will

prioritize safety and equity.

• The District’s top 20 freight bottlenecks, or roadways with the highest total delay in

2019, align with freight corridors the agency has identified for improvements,

including I-395 and the I-295/Malcolm X interchange. While these projects will

improve freight performance in the long term, DDOT anticipates that they will have

negative short-term impacts on truck travel time reliability during construction.

• To help mitigate freight-related congestion, DDOT has hired a dedicated staff to

manage curbside commercial vehicle loading zones, optimized signal timing along

priority freight corridors; is researching policy and technology improvements to its

oversize/overweight vehicle permitting process, and developing a delivery demand

management program to reduce loading impacts.

• Regarding heavy vehicles, the District manages an oversize/overweight permitting

process, coordinates with its enforcement partners, is investing in upgrades to its

existing weigh station and weigh-in-motion facilities, and implements its

transportation asset management plan.

13

• DDOT is investing in technology to support enforcement and data collection via WIM

technology upgrades and automated enforcement technology.

• Freight needs cluster around constraints—limited roadway and curb space, aging

infrastructure, low clearances—and increased demands on those constraints, such

as growing population, economy, e-commerce, and extreme weather.

Chapter 7 Highlights: Freight Advisory Committee Input

• The District works with a group of stakeholders that incorporate the roles and

expertise described in Section 11125 of the IIJA to stand up a District Freight

Advisory Committee.

• DDOT shared this update with these stakeholders, held a virtual open house to

provide context, and requested comments for the agency to incorporate before its

submission to FHWA, explaining that a larger, consultant-led update was underway.

• DDOT has received and incorporated comments from more than 8 freight advisory

committee members in this update.

Chapter 8 Highlights: Recommendations, Funding & Investment Plan

This plan incorporates the following recommendations:

• Maintain a freight advisory committee

• Improve curbside loading operations

• Focus additional resources on inter-jurisdictional cooperation in rail planning to

preserve and enhance rail throughput

• Provide publicly available comprehensive & up to date truck route information

• Update Freight Design Guidelines

• Invest in Freight Data

• Coordinate with FMCSA, NHTSA, and Vision Zero to support road safety

• Coordinate with Bus Priority / Sustainable Transportation Projects to maintain

goods movement and mitigate truck conflicts

• Update Oversize/Overweight Routing Process and Policy

• Support Existing Weigh In Motion Systems

• Invest in Truck Enforcement Equipment

• Study Positive Truck Route Signage

• Regularly Update State Freight Plan

• Invest and Implement Innovative Freight Delivery Practices

o Sustainable delivery pilot program

o Delivery Demand Management Program

• Invest in Paving Repair

• Maintain & Improve DC Port.

14

• Study Geometric & Safety Improvements along I-295

• Rehabilitate Minnesota Ave Bridge over East Capitol Street

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs (IIJ) Act requires states and MPOs to provide an

eight-year financially constrained freight-investment plan to include a list of priority projects

and proposed funding within their freight plans (49 U.S. Code § 70202). The District of

Columbia NHFP fund apportionment totals $50.67 million for FY 2023 through FY 2030.

DDOT’s approach for allocating federal freight funds is to apply the funding for federal

fiscal years 2023-2030 to projects preserving and optimizing existing resources, and

assessing the potential of innovative practices to mitigate freight movement impacts.

Chapter 9 Highlights: Implementation Plan & Performance Measures

This plan incorporates updated performance measures to assess success and meet

achievable outcomes over the next eight years:

• Sustainability: Interstate congestion as measured by the Truck Time Reliability

Index, GHG emissions from the transportation sector, and percentage of

Alternative Fuel Corridors (AFCs) with DCFCs (direct current fast charging)

• Mobility: number of vehicle permits issued with appropriate routing and

engineering assessment (as needed), number of functioning static weigh station

and weigh in motion (WIM) systems, percent of primary freight route pavement in

good condition, number of tickets issued for unauthorized vehicles in loading

zones, number of tickets issued to vehicles in violation of through-truck

restrictions, number of tickets issued to commercial vehicles for double-parking,

number of street redesign and reconstruction projects utilizing freight

considerations checklist, and number of feeders on schedule for undergrounding

per the biennial plan

• Safety: number of crashes involving trucks, number of fatalities in crashes

involving trucks, and number of serious injuries in crashes involving trucks

• Security: number of hazardous material incidents involving truck, water, or rail

• Management and operations: percent of bridges on primary freight routes in fair

or better condition, percent of freight route pavement in good condition, number

of emerging technology pilots implemented, number of operational loading zone

spaces, and timeframe to install or relocate loading zones by request

15

• Equity: number of projects assessed for equity

2.0 Introduction

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), passed on November 6, 2021, requires

each State receiving funding under the National Highway Freight Program to develop a

State Freight Plan that defines the immediate and long-range planning activities and

investments of the State with respect to freight, and adds several new required elements

that a State Freight Plan must include. This update serves as the guiding document for

freight in the District while a larger consultant-led state freight plan update is underway.

Launched December 2022, the consultant-led update will include more in-depth data

analysis and community outreach and will be submitted to FHWA in December 2023. In the

interim, this update includes all of the required elements of a state freight plan per IIJA

specifications.

The District of Columbia (the District) is a dense urban environment with a diverse mixture

of land uses that place significant demand on the city’s transportation infrastructure. The

city’s role as an employment center for the region creates a high volume of commuter

traffic in peak hours, while the consumer driven economy generates significant demand for

freight movement.

The District has experienced a substantial population increase and sustained economic

development over the past decade, generating a growing demand for freight activity. In

2021, the District had an estimated population of 670,050. While businesses continue to

thrive, contributing to the city’s economy, population growth increases demand for housing,

employment, and goods and services, all of which create increasing pressure on the city’s

transportation network.

2. INTRODUCTION

16

The 2022 INRIX Traffic Scorecard

2

ranked the Washington, DC Region as the 20

th

worst in

congestion among major metropolitan areas – behind Los Angeles, San Francisco, New

York and Boston. And congestion is expected to get worse: According to the Metropolitan

Washington Council of Governments’ 2022 Congestion Management Process Technical

Report, the Metropolitan Washington region is expected to be home to 23% more residents

and 29% more jobs by 2045, creating a demand on roadways that is expected to outpace

the increase in supply, and leading to significant increase in congestion

3

.

In addition to the congestion caused by a high volume of private vehicles traveling into the

city, the District’s transportation infrastructure is shared with other modes such as transit

vehicles and bicyclists. Many of the city’s residents rely on the extensive bus system and

services to conduct their daily business. Surface transit options such as the Washington

Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (WMATA) Metrobus, DDOT’s Circulator, and the

development of a streetcar system, initiated on H Street NE, provide an essential service to

the estimated 24 percent of District households that do not have access to motor vehicle.

In addition to local transit services, the District’s transportation network also supports

regional transit with over 300 commuter buses entering the city every weekday. As well as

the traditional transit options, the District also has a well-established and successful bicycle

program. In 2010, DDOT launched the largest bike-sharing program in the country (Capital

Bikeshare) and has installed over 50 miles of bike lanes and 64 miles of signed bike routes

in the intervening years. All of these modes are important parts of the District’s

transportation network, but they create competing demands on infrastructure that has few

options to expand.

In 2011, the District moved $21.7 billion and 16.8 billion tons in domestic goods to, within,

and from the District. By 2040, the District’s freight system will move over $61.2 billion

worth of goods, weighing 28.9 billion tons. In order to accommodate this projected increase

in freight movement, the District Freight Plan will outline freight transportation strategies

and recommendations to support sustainable economic growth and balance the needs

between communities and various industries in the District.

2

https://inrix.com/scorecard/#city-ranking-list

3

MWCOG 2022 Congestion Management Process Technical Report:

https://www.mwcog.org/file.aspx?D=ioxzbWHMefHpfjALW7Km9f93c7oxosp01AvVc%2fwclvo%3d&A=tE1fNwsPMzwIS

k6ug%2b6UeMZgnRrrgdda6gMUaGSBVH4%3d

17

3.0 Strategic Goals & Objectives

1.1. Federal Requirements

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act requires that States complete a State Freight

Plan in order to obligate freight formula funds under 23 U.S.C. 167.

There are 17 federally required elements that all State Freight Plans must address for each

of the transportation modes. The list below indicates where that requirement can be found

within this guiding document:

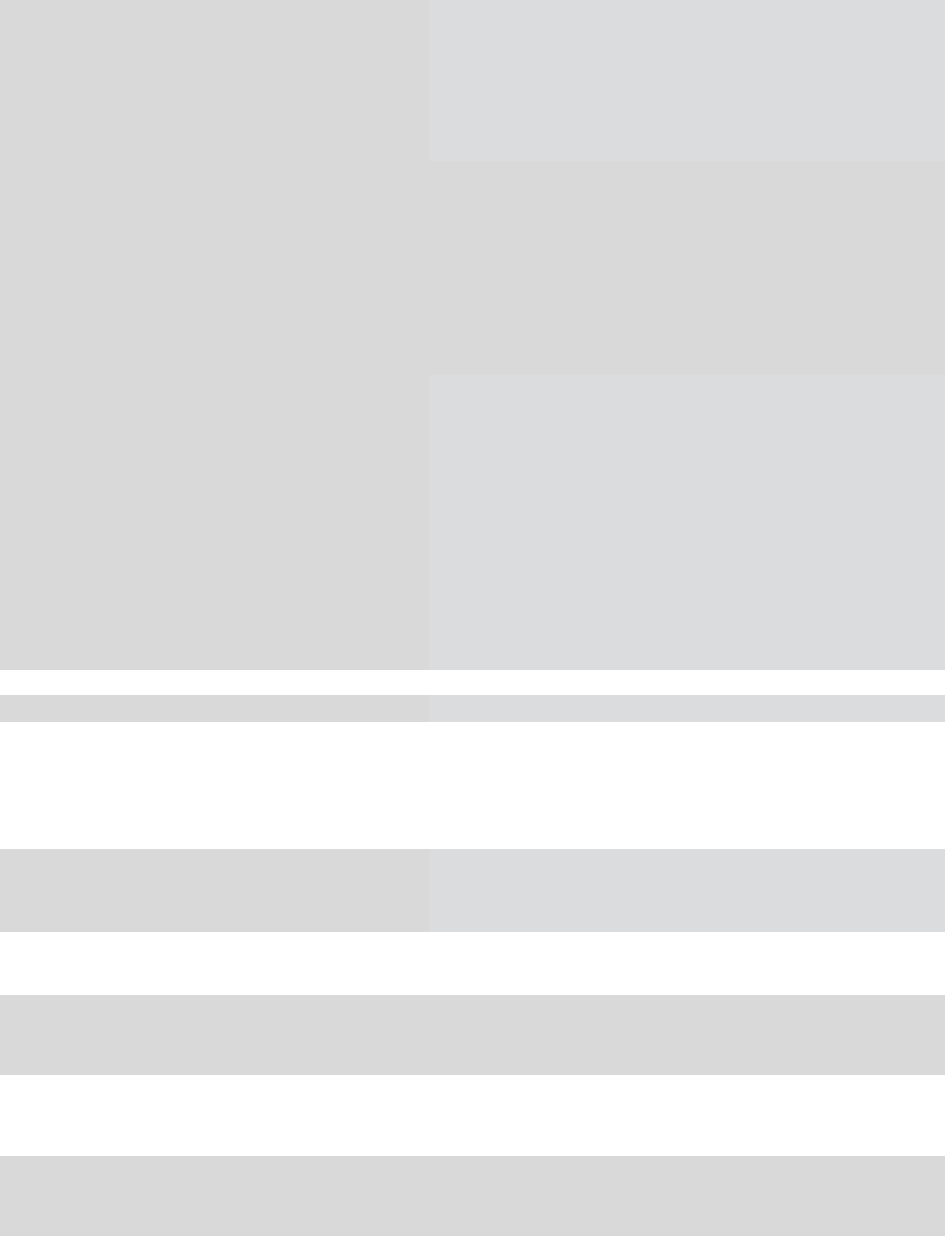

Figure 1 I Required State Freight Plan Elements and Location in Freight Plan Update

#

Required State Freight Plan Element

Plan Location

1

an identification of significant freight system trends, needs,

and issues with respect to the State

Chapters 5 and 6

2

freight policies, strategies, and performance measures that

will guide the freight-related transportation investment

decisions

Chapters 3 and 9

3

When applicable, a listing of—

--multimodal critical rural freight facilities and corridors

designated within the State

--critical rural and urban freight corridors designated within

the State

Chapter 4

4

how the plan will help meet the national multimodal freight

policy goals and the national highway freight program

goals

Chapter 9

5

description of how innovative technologies and operational

strategies that improve the safety and efficiency of freight

movement were considered

Chapter 6

3. STRATEGIC GOALS & OBJECTIVES

18

6

where heavy vehicles (including mining, agricultural,

energy cargo or equipment, and timber vehicles) are

projected to substantially deteriorate roadway conditions,

ways to reduce or impede the deterioration

Chapter 6

7

An inventory of facilities with freight mobility issues, such

as bottlenecks, within the State, and for those facilities that

are State owned or operated, a description of the

strategies the State is employing to address those freight

mobility issues

Chapter 6

8

consideration of any significant congestion or delay caused

by freight movements and any strategies to mitigate that

congestion or delay;

Chapter 6

9

a freight investment plan

Chapter 8

10

the most recent commercial motor vehicle parking facilities

assessment conducted by the State:

--- the capability of the State, together with the private

sector, to provide adequate parking facilities and rest

facilities for CMVs engaged in interstate transportation

---the volume of commercial motor vehicle traffic in the

State ---whether there are any areas with a shortage of

adequate CMV parking facilities, including an analysis of

the underlying causes

Chapter 4

11

the most recent supply chain cargo flows in the State,

expressed by mode of transportation

Chapter 5

12

an inventory of commercial ports in the State

Chapter 4

13

consideration of the findings or recommendations made by

any multi-State freight compact to which the State is a

party under sec. 70204

Chapter 6

14

the impacts of e-commerce on freight infrastructure in the

State

Chapter 5

15

considerations of military freight

Chapter 5

16

Strategies and goals to decrease:

--the severity of impacts of extreme weather and natural

disasters on freight mobility;

--the impacts of freight movement on local air pollution;

--the impacts of freight movement on flooding and

stormwater runoff; and

--the impacts of freight movement on wildlife habitat loss;

and

Chapter 6

17

Consultation with the State freight advisory committee

Chapter 7

1.2. State Strategic Vision, Goals & Objectives

The strategic vision for the District of Columbia Freight Plan is intended to inform long-

term planning and transportation decision-making for the District and the region. The

19

strategic vision includes high level goals for freight planning within the District as well

as specific elements of what will comprise the future system to best serve the District.

The vision is consistent with the current Federal transportation legislation, IIJA, which

places new emphasis on e-commerce, equity, and environmental concerns within a

multimodal freight network. The vision also builds on the National Capital Region

Freight Plan 2016, developed by the Transportation Planning Board of the Metropolitan

Washington Council of Governments. Elements of this strategic vision include mobility,

sustainability, operations, safety, security, and equity, and align with moveDC, the

District’s long-range transportation plan.

1.2.1. Vision

The strategic vision is of an efficient goods movement system that is sustainable,

safe, and secure. All projects will be reviewed and prioritized through an equity lens

and will work to eliminate or minimize negative impacts on historically burdened

communities. Additionally, the vision is of reliable freight operations to carry the goods

that will enable the District economy to continue to grow and the residents and public

and private sector establishments to thrive. District will strategically invest in

technology to support the goals of this vision. The following subsections outline the

details of the six elements of this strategic vision.

1.2.2. Goal 1: Mobility

The District’s moveDC goal of mobility, which includes improving system reliability,

accessibility and congestion management for goods movement as well as commuters,

is key to supporting the District’s economic vitality. This element of the strategic vision is

for a freight transportation system that can efficiently provide residents, businesses, and

public sector organizations in District with the goods they require. Continued growth in

employment and business activity in the District will be enabled by a freight

transportation system that is efficient and reliable, and able to handle increased goods

volume to support the District’s continued growth. The District’s transportation system

should provide for a reliable, accessible goods movement system to support the

District’s tax-paying business community and tax-paying residents.

1.2.3. Goal 2: Sustainability

The District has a goal to be carbon neutral by 2050, and transportation will be a key

sector for achieving this goal. The District’s Sustainable 2.0 plan sets a target of

reducing GHG emissions from the transportation sector by 60 percent. The

Department of Energy and Environment regularly tracks the District’s GHG emissions

to measure progress towards these goals.

Improving sustainability within the freight sector is a key element of the strategic

vision. As freight transportation equipment is a significant source of criteria pollutants

and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the plan envisions the District will benefit from

20

increased use of cleaner later-generation diesel engines, increased use of auxiliary

power units to reduce truck and rail locomotive idling, and greater use of advanced

routing and traffic information by truckers to reduce congestion, which contributes to

pollution, as well as noise impacts on communities.

Additionally, innovative last-mile delivery solutions such as curb management

strategies, delivery microhubs, and common carrier lockers are also effective methods

to reduce emissions and vehicle miles traveled within the District, and can help

minimize the negative environmental impacts of freight movement (especially on

historically over-burdened communities); these are discussed in more detail in the E-

Commerce and Related Planning Considerations section.

Rail freight operations through the District are also important to the region and will be

taken into consideration in rail planning. Investments in regional rail infrastructure,

such as Long Bridge, will enhance the operational capabilities of both rail freight and

passenger operations by removing existing bottlenecks and clearance restrictions, and

possibly expand rail service to the District. These actions would not only benefit

existing or potential rail users, but also reduce of the number of trucks traveling

through the region, producing safety and environmental benefits for the area.

1.2.4. Goal 3: Management and Operations (State of Good Repair)

As one of its moveDC goals, DDOT will ensure the state of good repair for

existing assets by investing in maintenance and operations, and the advances in

technology that will support a state of good repair for District infrastructure.

This vision includes supporting a robust paving plan and enforcing vehicle size

and weight regulations. Asset management such as signal timing improvements

and updated roadway designs that accommodate truck movements supports

efficient freight operations while minimizing traffic impacts. This vision also

incorporates truck operating needs into transportation planning and land-use

planning. Truck corridor preservation, truck turning radii considerations, loading

dock access provision, assuring truck parking availability, and efficient truck

permitting are all to be incorporated into comprehensive planning in the District.

Support for continued maritime and rail freight operations will also be

incorporated into the plan to preserve access to non-truck modes of transport.

The vision is for all planning in the District to have freight operations

incorporated due to the shared use of the transportation system by freight,

transit, personal vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians. Investing in advanced

permitting systems will support the integrity of District infrastructure, along with

improved data collection for planning and tracking purposes. Roadway

engineering and intelligent transportation system technologies will accommodate

21

the operational characteristics of freight equipment while minimizing pavement

wear and infrastructure damage.

1.2.5. Goal 4: Safety

Safety is a goal laid out in moveDC; this goal states that “DDOT will design and

manage a transportation network that offers safe and secure travel choices for all

users.” Safety improvements and considerations in planning will result in fewer

crashes, property damage, injuries, and loss of life related to goods movement.

Developing street designs that accommodate goods movement while

incorporating safety improvements aim to reduce conflicts between trucks and

other transportation system users. This supports the District’s Vision Zero

commitment to having zero fatalities or serious injuries on District streets by

2024

4

. Investing in technologically advanced weigh stations and weigh-in-motion

systems support enforcement efforts and integration into national motor carrier

safety databases, as well as provide better understanding of existing conditions.

1.2.6. Goal 5: Security

The transportation system will provide for the secure movement of goods. Public

agencies responsible for security of the transportation system will have access to

information and an educated freight system workforce as partners in assuring

security for freight. Freight plans will be developed with considerations for the

special security requirements of the District, including cooperation with the agencies

responsible for security.

1.2.7. Goal 6: Equity

In the MoveDC plan, transportation equity is defined as “the shared and just distribution of

benefits and burdens when planning for and investing in transportation infrastructure and

services. Just distribution means investing in the communities and areas that are in the

greatest need that include, but are not limited to:

• People of color

• People with low income

• People living with disabilities

4

Vision Zero DC: https://visionzero.dc.gov/pages/2022-update

22

• LGBTQ+ people

• Individuals who identify as female

• Youth and older adults

• Residents at risk of displacement

• People experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity

• Immigrant and refugee communities

• People with limited English proficiency and literacy”

This freight plan shares the equity goal of moveDC, which states that “DDOT will advance

transportation equity by evaluating its policies, planning, community engagement, and

project delivery to ensure public investments in transportation justly benefit all residents,

visitors, and commuters.” All projects at DDOT, including freight projects, are evaluated

based on an equity assessment within the agency’s project prioritization and budget

process. Additionally, the DDOT freight program is prioritizing projects that aim to lessen

negative freight impacts in overburdened communities, such as the positive truck route

signage study and sustainable delivery modes pilot project, which are currently underway.

4.0 Freight Infrastructure

1.0. Highway

The highway section describes the extent and condition of the roadway system that

serves trucking in the District. The section includes points of entry, principal corridors,

and pavement and bridge condition. The project team drew from freight survey data and

DDOT’s information management system to develop the highway profile.

The highway system serves several important functions in the District’s freight

transportation system, including mobility for trucked freight, connectivity between

freight generating facilities to, from, or within the District, and connectivity between

airports, waterways, railroads, and businesses within the District of Columbia.

Trucking accounts for almost all of the inbound and outbound freight shipments in the

District. In terms of tonnage, 99.3 percent and 98.9 percent of inbound traffic moves by

truck, while in terms of value the shares are nearly identical at 99.5 percent and 99.9

4. FREIGHT INFRASTRUCTURE

23

percent, respectively.

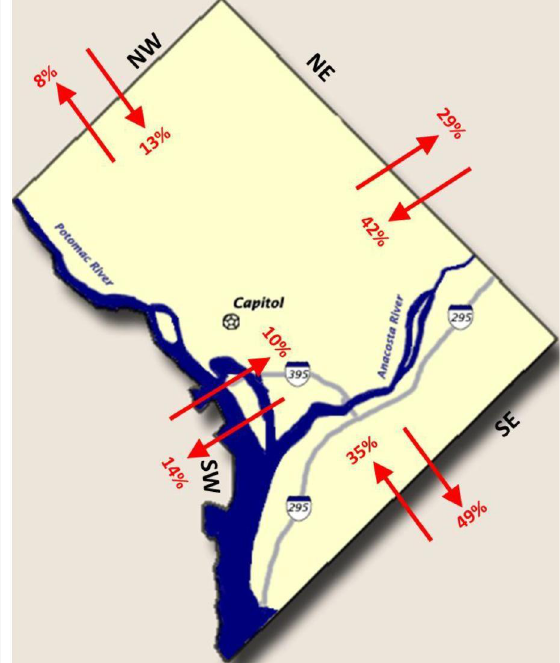

Almost all trucks operating in the District have either an origin or a destination within the

city. In other words, there is very little truck through-traffic within the city. Additionally,

more trucks enter the District from Maryland than from Virginia. Further, inbound and

outbound truck traffic is heavily concentrated to the east and south of the District. The

percent of truck traffic entering and exiting the District is shown in Figure 1.

More than 40 percent of inbound trucks enter the District from the northeast on routes

such as US 1, and US 50. The eastern part of the District, and the areas of MD east of

the District, are home to many warehouses and transfer points, particularly along New

York Avenue and in the Landover and Lanham, Maryland, areas. Additionally, truck

traffic from Baltimore and other locations on the Eastern Shore enters the District from

the east. There is also substantial truck traffic, 35 percent, from Maryland to southeast

Washington. Similarly, for outbound traffic, over 75 percent of trucks leave via the

District’s eastern and southern borders with Maryland.

Figure 1: Inbound and Outbound Truck Traffic

24

In 2010, DDOT developed a city-wide truck and bus route system to improve the

management and monitoring of truck and bus traffic in the city under a single,

comprehensive regulatory system. Specific routes were designated as part of the

truck and bus route system based on a variety of factors, which included

engineering characteristics, roadway classifications, planner review, industry and

community feedback, and field observations. Routes included in the truck and

bus route system were designated as primary or restricted.

A “primary route” designation indicates the road meets technical standards, can

handle high truck traffic volumes, or serves major truck and/or bus destinations. A

“restricted route” designation indicates a road that may not be used by trucks or

buses for any purpose due to security reasons, inadequate capacity, or the

residential quality of the area. Roads in the District that have neither a “primary

route” or “restricted route” designation may have trucks and/or buses travel on

them, but only for an official business need. All trucks or buses which must travel

on a non-designated road must take the most direct access road to their

destination, conduct their business (i.e. deliver a package) and take the most

direct road back to a ‘primary route’ for travel through the rest of the city. The

District’s truck and bus route and restrictions map is shown below.

Figure 2: Truck Routes in Washington, DC

25

1.0.0. Pavement Type & Condition

Pavement conditions on the District’s roadways are surveyed regularly to

26

measure rutting, cracking, and roughness. This information is summarized into a

pavement condition index (PCI) that ranges from zero to 100; where 80-100

represent good condition, 65-79 fair, and <64 poor. In general, trucks, due to their

greater per-axle loads, cause more roadway damage than automobiles. It is

important to note that proper distribution of weight across axles helps to minimize

the impact of additional weight on pavement and is a greater factor in

determining the extent of damage than the absolute weight of a load (i.e., the

lower the weight per axle the lesser the road damage caused by that vehicle).

In the District, asphalt overlay on concrete accounts for 100 percent of the

primary route lane-miles. As per a recent DDOT transportation asset

management analysis

5

, 91 percent of DDOT-owned National Highway System

pavements were in good or fair condition, 99 percent of DDOT-owned Interstate

Pavements were in good or fair condition, 90 percent of DDOT-owned Non-

Interstate NHS Pavements were in good or fair condition, and 82 percent on non-

DDOT owned pavements were in good or fair condition.

1.0.1. Bridge Characteristics & Condition

The entire bridge system within the District is comprised of 265 bridges, 160 of

which are on the primary truck route network. Individual analyses of bridge

characteristics (material, age, and condition) along the primary truck route

network are beyond the scope of this task, but in general, 88 percent of NHS

Bridges are in good or fair condition, 92 percent of DDOT-owned NHS bridges

are in good or fair condition, an only 42 percent of National Park Service-owned

NHS bridges are in good or fair condition

6

.

1.0.2. Loading Zones

Commercial loading zones are short-term curbside metered parking zones exclusively for

commercial vehicles. These zones provide local businesses a designated space to receive

deliveries when off-street options are not available. To keep these zones free for active

loading – and reduce double-parking in travel or bike lanes – longer-term commercial

vehicle parking should be accommodated off-street, where feasible.

The District has more than 600 commercial loading zones, each with signs that specify

days and hours of operation, which are typically between 7:00 AM and 6:30 PM, for time

5

DDOT TAMP October 2022 Report

https://ddot.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ddot/TAMP_Master_SlideDeck_v3.pdf

6

DDOT TAMP October 2022 Report

https://ddot.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ddot/TAMP_Master_SlideDeck_v3.pdf

27

periods up to 2 hours at a time, unless otherwise posted. A map of commercial loading

zones is available at: https://godcgo.com/dc-truck-and-bus-map.

Commercial vehicles must pay to use commercial loading zones by purchasing annual or

daily permits via DDOT’s Transportation Online Permitting System, TOPS

(https://tops.ddot.dc.gov/), or by paying on a per-use basis via the District’s pay-by-cell

provider (posted on the sign).

1.1. Rail

The rail profile describes the use, extent, and condition of the freight rail system

that serves the District. This section is sourced from DDOT materials. Freight

railroads in the U.S. are generally categorized as Class I railroads, Class II or

regional railroads, and Class III or short-line railroads. Some short-line railroads

are further classified as terminal railroads.

Approximately 44 million tons of cargo is shipped by rail that travels through, to or

from the District. The District of Columbia is currently served by two Class I

railroads; there is also one Class III switching or terminal railroad used for

passenger trains at Union Station. Table 1 summarizes the mileage data for the

two freight railroads operating within the District of Columbia, CSX Transportation

(CSXT) and Norfolk Southern Railway (NS). NS does not own railroad lines but

has leased the trackage rights from CSX Transportation. CSX currently serves 3

customers in the District.

Table 1: Freight Rail Owners and Operators in Washington, DC

RAILROAD

REPORTI

NG

MARKS

WASHINGTON, DC RAIL ROUTE MILES

MILES

OPERATED

MILES

OWNED

MILES OPERATED

VIA TRACKAGE

RIGHTS

Class I Railroads — CSX

Transportation

CSXT

20

18

2

Class I Railroads — Norfolk Southern

Railway

NS

13

-

13

Source: CSXT and NS 2012 R-1 Annual Reports; AAR State Fact

In addition to 20 miles of active track, there are 6.2 miles of inactive rail tracks

located parallel to and just west of I-295 near the Joint Bolling Anacostia Base.

The city is looking into alternative transportation uses for this right-of-way.

The District’s rail network is expected to play a prominent role in the country’s

growing international and domestic rail intermodal movements. DC is located on

one of CSXT’s major intermodal routes. As such CSXT has undertaken a

massive rail infrastructure improvement program to remove existing restrictions

to the movement of double-stack container trains in the DC area. Currently, 30

freight-carrying trains enter the District of Columbia daily; this number is

28

expected to increase to 34 daily trains by 2040.

One such prominent investment was the Virginia Avenue Tunnel Project in

southeast Washington, DC. The tunnel, running under Virginia Avenue, featured

west and east portals near 2nd Street SE and 11th Street SE, respectively. The

project, begun in 2015, replaced the old tunnel with two new tunnels to allow for

double-stacked freight containers to travel through the tunnel. The project,

including streetscape restoration, was completed in 2018.

The Long Bridge Project is another prominent rail investment. Long Bridge is a

two-track railroad bridge owned by CSXT that was constructed in the late 19th

and early 20th century. It serves CSXT, Amtrak, and Virginia Railway Express

(VRE), is the only rail bridge that connects the District of Columbia and the

Commonwealth of Virginia, and is a major choke point for both freight and

passenger rail movements.

The Long Bridge Project will construct two additional tracks on a new bridge structure

over the Potomac River and railroad infrastructure improvements between the RO

Interlocking in Arlington, Virginia, and the L’Enfant (LE) Interlocking near 10th Street

SW in the District of Columbia. The purpose of the Project is to provide additional long-

term railroad capacity and to improve the reliability of Amtrak, VRE, and CSX

Transportation (CSXT) railroad service. This improvement project is currently being

managed by the Virginial Passenger Rail Authority and is in the preliminary design

stage, with construction scheduled to be completed by 2030.

Ongoing improvements to the rail freight network will further enhance the importance of

the District’s network by providing a key to the double-stack intermodal container freight

route from the East Coast to Midwest markets. Although the DC freight rail network is

small in terms of rail infrastructure mileage and the amount of freight currently

originating and terminating in the District, it plays a key role in the regional freight

network and with regard to local and regional rail passenger operations, with over 90

intercity or commuter passenger rail trains operating over the CSXT network daily.

Although these improvements will not likely result in the District becoming an intermodal

hub, it will enhance the operational capabilities of both rail freight and passenger

operations by removing existing bottlenecks and clearance restrictions, and possibly

expand rail service to District markets by reducing rail transportation costs. These

actions would not only benefit existing or potential rail users, but also result in a

reduction of the number of trucks traveling through the region producing safety and

environmental benefits for the area.

1.2. Air

This section provides a summary review of the airport facilities that serve cargo activity

in the National Capital Region. Information in this section is sourced from the latest

29

Washington-Baltimore Regional Air Cargo Study

7

. The DC region is currently served by

three airports, Baltimore Washington International (BWI), Washington Dulles

International Airport (IAD), and Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA).

Both passenger airlines and dedicated cargo carriers transport high-value, time-

sensitive goods through these hubs. While these three airports are widely known for

their role in transporting thousands of travelers on a daily basis, both BWI and IAD also

play a substantial role in the movement of goods, or cargo, to and from the region.

Since DCA’s role in air cargo is so minor, it will not be discussed further.

Air cargo accounts for the smallest share of freight in terms of volume (weight), by

freight mode, but it accounts for the largest share in terms of monetary value per

ton. Air cargo is used to transport high-value commodities and/or commodities

requiring just-in-time delivery. These may include medicines and vaccines, fresh

food, flowers, or other perishable items, as well as precision-engineered and

manufactured electronic components.

Air cargo industry is forecast to expand worldwide. In terms of demand, both BWI

and IAD are poised to embrace this growth. BWI has historically served domestic

demand for air cargo. That market is expected to continue. Contrastingly, IAD’s

growth in air cargo will be more focused in the international sector. Both markets

are forecast to grow through the year 2040. Accessibility from the airports to other

parts of the region, however, will generally constrict between 2015 and 2040 due

to growing traffic volumes, a potential risk for the delivery of time-sensitive cargo.

Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD) is located 26 miles west from

downtown Washington, DC, located in Fairfax and Loudoun Counties, VA. IAD is

situated with direct access to Dulles Greenway Toll Road, and is 14 miles from I-

495 (Capital Beltway) which connects to multiple metropolitan areas. Connectors

through I-495 include: I-270, I-95, MD 201, and MD 4. The interstate also

provides direct access to Andrews AFB (45 miles from IAD).

Baltimore Washington International (BWI) is situated with direct access to I-195,

six miles from I-95 which connects to multiple metropolitan centers along the East

Coast. Connectors through I-95 include I-495, MD 100, I-195, I-695, I-895, MD

295, and I-395. The interstate also provides direct access to Andrews AFB (37

miles from BWI) and the Port of Baltimore seaport (10 miles from BWI).Air cargo

trends at BWI and IAD airports are described below.

7

Washington Baltimore Regional Air Cargo Study - 2015.

https://www.mwcog.org/documents/2017/02/15/washington-baltimore-regional-air-cargo-study-airport-access-

freight/

30

Baltimore Washington International Airport (BWI)

Between 2008 and 2014, air cargo increased slightly from 102,000 to 105,000 metric

tons. Through the year 2040, air cargo at BWI is expected to increase annually,

although modestly. Domestic air cargo accounts for the greatest share of total freight

handled at BWI, which is expected to remain at over 90% of total freight at BWI.

8

Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD)

Air cargo at IAD decreased sharply from 334,000 metric tons to 267,000 metric tons

between 2008 and 2014, though forecasts call for air cargo growth through 2040. IAD’s

air cargo market share position in the air system planning region will continue to expand

during the forecast period. This expansion will be fueled by increases in international air

cargo demand. IAD has extensive international service to other markets, including

Europe and Latin America, which fuel the bulk of the international air cargo demand.

Air cargo trucked in and out of the DC market will likely remain on interstate and

other limited access highway systems as much as possible, due to the

congestion and access issues on the District’s arterial road system.

1.3. Maritime / River

Although the District’s boundary encompasses two major rivers, neither is a

significant source of freight movements, due to the District’s service-based

economy, the rivers’ lack of accessibility, and lack of shipping infrastructure. The

region’s major rivers are the Potomac, Anacostia, and Occoquan. According to U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers Waterborne Commerce Statistics (USACE), shipments

totaled 110,000 short tons of one inbound commodity in 2011: gasoline. Earlier

years (2000-2006) show 600,000-700,000 short tons total, due to shipments of

aggregate, probably for construction purposes. Some other tonnage shipments are

suppressed in the USACE data due to confidentiality.

Shipping the gasoline by truck instead of by pipeline would add 10 truck trips per

day, assuming 300 tons of gasoline per day and roughly 30 tons of gasoline per

tank truck. As a share of total truck traffic, this number is not significant in the

regional context.

There is also a small U.S. government maritime operation, by the U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers along the Anacostia River at the edge of a property that used to be a

Washington Gas gas manufacturing plant (closed in 1983, demolished in 1988).

The U.S. government owns a 0.35-acre portion of the old gas plant property and it

8

Washington Baltimore Regional Air Cargo Study - 2015.

https://www.mwcog.org/documents/2017/02/15/washington-baltimore-regional-air-cargo-study-airport-access-

freight/

31

is managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Army Corps uses this small

section as a station for debris collection boats that patrol the Anacostia and

Potomac Rivers.

1.0. Commercial Ports

Although the District encompasses two major rivers, neither is a significant source of

freight movements due to the District’s service-based economy, the rivers’ lack of

accessibility, and a dearth of shipping infrastructure. The region’s major rivers – the

Potomac, Anacostia, and Occoquan – are part of a Federal initiative, known as the Marine

Highway Program, to provide financial incentives for investment that increases waterborne

freight and reduces highway demands. This is known as the M495 Marine Highway

corridor. These incentives may encourage shippers to look for more cost-effective means

of transporting commodities from and to the District. In the meantime, the only functional

dock located on District land that serves as a commercial port – commonly recognized as a

place where cargo is transferred between ships and trucks, trains, pipelines, storage,

facilities, or refineries, as per the Bureau of Transportation Statistics – is in Ward 6, on S

Street SW, adjacent to the South Capitol Street Bridge on the Anacostia River.

Figure 2 I Map of general location of S Street SW Dock

District

Dock

32

According to the District’s most recent research into the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Waterborne Commerce Statistics (USACE), shipments totaled 110,000 short tons of one

inbound commodity in 2011: gasoline. Earlier years (2000-2006) show 600,000-700,000

short tons total, due to shipments of aggregate, probably for construction purposes.

Indeed, DDOT has used the S Street SW dock to support the inspection, maintenance and

construction of bridges. It has also been used by PEPCO to unload large transformers and

more recently as the location where the Captain White Seafood barge was dismantled after

leaving the SW Waterfront. DDOT does not have free access to any other developed dock

in the District, which makes this facility a significant and important asset.

In order for the District to continue to benefit from the existing freight capacity provided via

maritime transportation, this S Street SW District Dock will need repair and investments to

maintain its current use of providing water access for DDOT bridge inspection,

maintenance and construction projects.

There is also a small U.S. government maritime operation by the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers along the Anacostia River adjacent to property to a former Washington Gas

manufacturing plant (closed in 1983, demolished in 1988). The U.S. government owns a

0.35-acre portion of that old gas plant property, and it is managed by the U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers. The Army Corps uses this small section as a station for debris collection

boats that patrol the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers.

The District as a whole will also need to consider and avoid the impacts of encroachment

by waterfront development into berthing locations and navigation channels in the rivers.

This potential conflict, however, could also be an opportunity: The private waterside

development, The Wharf, for instance, has a large crane that may be able to add

redundancy and serve as a model for public-private partnership. The Wharf has a roadway

immediately along the water that may be serviceable for some water borne freight. The

Wharf facility could be a model to draw on for a public-private partnership at the Buzzard