Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Background & Problem Statement 4

Two key formats 5

Lifecycle of an SBOM 6

How to produce SBOM? 6

How to deliver SBOMs? 7

How to update SBOM? 7

How to consume SBOMs? 7

Overview of Key Formats 9

SPDX 9

Description 9

Use Cases 11

Key Features 11

SPDX and SBOM 11

Future Directions 11

SWID Tag 12

Description 12

Use Cases 14

Key Features 14

SWID tags and SBOM 14

Future Directions 14

Translation and Harmonization Guidance 15

Example Scenario 15

Example in SPDX 16

Example in SWID 17

Future work on SBOM formats 19

Software Identifier challenges 19

Tooling challenges 19

SBOM Delivery and Distribution challenges 20

Software Component Modification 20

SBOM formats for higher trust and provenance 20

Related Formats Surveyed 21

CoSWID Tag 21

CPE 24

CycloneDX 24

Grafeas 26

in-toto 26

2

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Background & Problem Statement

Modern software systems involve increasingly complex and dynamic supply chains.

Unfortunately, the composition and functionality of these systems lacks transparency; this

contributes substantially to cybersecurity risks, alongside the cost of development, procurement,

and maintenance. This has broad implications in our interconnected world; risk and cost affect

collective goods, like public safety and national security, in addition to the products and services

upon which businesses rely.

The NTIA Software Transparency Working Group on Standards and Formats was formed to

assess available current formats for software bills of materials as well as forward-looking

use-cases identified by other working groups or communities of practice. The working group

1

investigated existing standards, formats and initiatives as they apply to identifying the external

components and shared libraries (proprietary or open source) used in the construction of

software products. The group analyzed efforts already underway by other groups related to

communicating this information in a machine-readable manner.

We propose that increased supply chain transparency can reduce cybersecurity risks and

overall costs by:

● Enhancing the identification of vulnerable systems and the root cause of incidents

● Reducing unplanned and unproductive work

● Supporting more informed market differentiation and component selection

● Reducing duplication of effort by standardizing formats across multiple sectors

● Identifying suspicious or counterfeit software components

Collecting and communicating this information in such a manner can lower the cost, increase

the reliability of, and increase our ability to trust our digital infrastructure.

The initial goals of this working group were to:

● Investigate the options available today

● Document workable and actionable machine-readable formats

● Acknowledge that no single solution/format will be required (i.e., we will not “proclaim a

winner”)

● Determine how the solutions can work in harmony, since different formats were designed

1

This working group operated in parallel and coordination with three other efforts in the NTIA

multistakeholder process on Software Component Transparency: a working group devoted to defining the

baseline SBOM requirements and definitions, a working group documenting use cases and benefits of

software transparency, and a working group designing and executing an initial, early-stage proof of

concept for the medical device industry and their hospital customers. The working groups and the broader

community of interest met in person or virtually approximately every two months from July 2018 to

September 2019. More information about the process is available here:

https://www.ntia.doc.gov/SoftwareTransparency The related documents are available at

https://ntia.gov/SBOM.

4

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

to address the requirements of different constituencies (e.g. developers, CFOs

managing software entitlements), and mapping between well-documented formats is

technically feasible.

● Support international feedback and buyin to solutions as supply-chain security and

software integrity is not just a US problem, and participation in this process is global.

Two key formats

The working group identified two formats in widespread use: Software Package Data eXchange

(SPDX), an open source machine-readable format stewarded as a de facto industry standard by

the Linux Foundation, and Software Identification (SWID), a formal industry standard used by

various commercial software publishers. Descriptions and use cases for each format, as well as

a mapping between them, are detailed below.

It is important to note that although these two formats contain overlapping information, they are

typically used at different points in the software life cycle, and are consumed by different types

of users. SPDX, a product of the open source software development community, is geared for

ease-of-ingestion within a developer workflow. The open source nature of the format, as well as

the availability of open source tooling to generate it, supports broad adoption by a large and

distributed population of commercial international organizations, as well as developers who may

not be associated with vendors. The accessibility of SPDX means that the sole developer of an

experimental library can generate an SBOM with minimal effort at no cost. These cost saving

and ready availability of open source tools is attractive to commercial organizations as well.

SPDX is useful in the “long tail” of upstream open source software componentry.

SWID tags were designed with software inventory and entitlements management in mind. SWID

tags support the inventory of commercial and open source software that is installed on a device

through locating the SWID tag associated with the software. A developer can use

freely-available guidance on the creation of SWID tags to configure their build pipeline to

produce SWID tags automatically during the software build and packaging process. With an

orientation around deployed software, SWID tags follow the binary and are updated as the

compiled codebase changes. This lends itself to integration with automated scanning, and a

host of risk-management use cases and tooling.

This document and this working group acknowledge that both formats can be used to generate,

exchange, and use SBOM data. While certain use cases may lend themselves to particular

formats, this working group does not endorse either specifically, and believes that each user

should select that which meets their needs. This document offers an explicit guide to translate

between the two for the “minimum viable” SBOM models to enable a more interoperable

ecosystem.

5

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Lifecycle of an SBOM

How to produce SBOM?

Information that goes into SBOMs can be best obtained from the tools and processes used in

each stage of the software lifecycle (See Figure 1, below). One may leverage existing tools and

processes to generate SBOMs. Such tools and processes include intellectual property review,

procurement review and license management workflow tools, code scanners, pre-processors,

code generators, source code management systems, version control systems, compilers, build

tools, continuous integration systems, packagers, compliance test suites, package distribution

repositories and app stores.

Figure 1: The Software lifecycle with multiple stages where underlying code might change, and

thus the SBOM would be updated to reflect the changes.

6

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Currently, not all off-the-shelf or open source software lifecycle tools have the capability to

generate SBOMs. Analysis of software may happen after initial generation. Suppliers should

consider enhancing or retrofitting existing tools and processes to generate and maintain

SBOMs.

SBOMs may be considered incomplete if some information about the materials added or

removed through the stages of software lifecycle is missing, or was never recorded. If the

SBOMs are incomplete, suppliers should make that clear so that consumers can make informed

use of SBOMs based on the available data.

How to deliver SBOMs?

At the moment, there is no set single way to transmit SBOM data downstream to the next user.

In open source products, the SBOM data can be stored as metadata, with pointers to

components. For compiled software, SBOMs can be bundled together with the software product

itself as a compendium and stored with the installed software. The data could also be made

available in portals controlled by the supplier or some other third party.

Stakeholders mentioned the potential value in accessing data from older SBOMs, so that users

can understand the underlying components of software at a specific point in time. For example,

a customer may want to know if a cloud-based service was potentially vulnerable at a certain

point in the past as part of a forensic breach investigation. This document does not offer

guidance on how to preserve past SBOMs.

How to update SBOM?

An SBOM should reflect the current state of a piece of software. If software or the software’s

underlying components are updated, then the list of underlying components should also be

updated accordingly to ensure that SBOM data itself is up-to-date. Except for the information

that is derived from the software artifact itself, other information in SBOM can be declarative, or

asserted by the author of the SBOM data. For example, the download location of the component

names can be part of the SBOM.

Similarly, if the information known about the software changes, or an error was made in the

original SBOM, a supplier may update the SBOM without updating the underlying code.

Declared information may have to be corrected,changed, or added over time. Such changes

can be appended to ledger-based SBOMs (see, e.g., the SPARTs project in Related Formats

section). Errata may have to be supplied and carried forward with a specific SBOM.

How to consume SBOMs?

For the most effective use of SBOM information, the data must be machine readable.

Consumption must incorporate machine-to-machine automated processes. Each of the use

cases discussed in the introduction (and further fleshed out in the Use Case document) can only

7

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

achieve maximum effectiveness by integrating into automated processes. It is also important

that the format can be translated into a human readable version.

Consumers may use SBOMs as input to their tools that support:

● asset management

● license and entitlement management

● intellectual property management

● regulatory and compliance management

● provisioning

● configuration management

● vulnerability management

● incident response

Usage of SBOMs for risk management may require additional risk data that may not be included

with SBOMs.

8

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Overview of Key Formats

SPDX

The Software Package Data Exchange (SPDX®) specification provides a standard language for

communicating the components, licenses, copyrights, and security information associated with

software components in multiple file formats.

Software development teams across the globe use the same open source components, but in

2010, there was little infrastructure available to facilitate collaboration or analysis, or to share

the results of analysis activities. As a result, many groups were performing the same work,

leading to duplicated efforts and redundant information. To save time, and improve data

accuracy, the SPDX project was formed to create a common data exchange format so that

information about software packages and related content could be collected and shared.

An SPDX document can be associated with a particular software component or set of

components, an individual file, or even a snippet of code. The SPDX project focuses on creating

and extending a “language” to describe the data that can be exchanged as part of a software bill

of materials, and be able to express that language in multiple file formats( RDFa, .xlsx, .spdx

and soon .xml, .json, .yaml) so that information about software packages and related content

may be easily collected and shared with the goal of saving time and improving accuracy.

The specification is a living document. As new use-cases are examined, it evolves. Care is

taken to provide backwards compatibility. Development progresses through collaboration

between technical, business and legal professionals from a range of organizations to create a

standard that addresses the needs of various participants in the software supply chain.

Companies and organizations (collectively “Suppliers”) are widely using and reusing open

source and other software components. Accurate identification of the software is key to

understanding if there may be a security vulnerability in it.

Description

The SPDX specification describes the necessary sections and fields to produce a valid SPDX

document. It is important to note that not all of these sections are required in every document.

The only one that is mandatory is to have a “Document Creation Information” section for each

document. Then it’s a matter of using the sections (and subset of the fields in each section) that

describe the software and metadata information you’re planning to share.

9

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

FIGURE 2 - Overview of an SPDX document. Souce:https://spdx.github.io/spdx-spec/

Each SPDX document can be composed from the following:

- Document Creation Information: One instance is required for each SPDX file

produced. It provides the necessary information for forward and backward compatibility

for processing tools (version numbers, license for data, authors, etc.)

- Package Information: A package in an SPDX document can be used to describe a

product, container, component, packaged upstream project sources, contents of a

tarball, etc. It’s a way of grouping together items that share some common context. It is

not necessary to have a package wrapping a set of files.

- File Information: A file’s important metadata, including its name, checksum licenses

and copyright, is summarized here.

- Snippet Information: Snippets can optionally be used when a file is known to have

some content that has been included from another original source. They are useful for

denoting when part of a file may have been originally created under another license.

- Other Licensing Information: The SPDX license list does not represent all licenses

that can be found in files, so this section provides a way to summarize other license

information that may be present in software being described.

- Relationships: Most of the different ways that SPDX documents, packages, files can be

related to each other can be described with these relationships.

- Annotations: Annotations are usually created when someone reviews the SPDX

document and wants to pass on information from their review. However, if the SPDX

10

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

document author wants to store extra information that doesn’t fit into the other

categories, this mechanism can be used.

Each document is capable of being represented by a full data model implementation and

identifier syntax. This permits exchange between data output formats (RDFa, tag:value,

spreadsheet), and formal validation of the correctness of the SPDX document. In the SPDX

specification 2.2 release, the additional output formats of JSON, YAML and XML are planned to

be supported. Further information on the data model can be found in Appendix III of the SPDX

Specification and on the SPDX web site.

Use Cases

● SBOM for software components

● Tracking of intellectual property (licensing, copyright) of software components

● Listing contents of a software dIstribution

● Container contents inventory

● Associating CPEs with specific packages

● Identifying provenance of lines of code embedded in files.

Key Features

● Documented artifacts can be checked using the provided hash values

● Rich facilities for intellectual property and licensing information

● Flexible model able to scale from snippets and files up to packages, containers, and

even operating system distributions

● Ability to add mappings to other package reference systems.

SPDX and SBOM

SPDX documents can capture SBOM data because they are able to represent all of the

components found in traditional software development and deployment. SPDX documents are

being used to represent distro .iso images, containers, software packages, binary files, source

files, patches, and even snippets of code embedded in other files. A rich set of relationships is

available to link the software elements together within documents, as well as between

documents. An SPDX document is able to link out via external references to NVD and other

packaging systems metadata.

Future Directions

● Information to indicate when/where/how known vulnerabilities have been remediated in

an update or patch.

● Enhancing the representation of pedigree and provenance information during chain of

custody discussions.

● Identification of use cases currently not able to be represented by an SPDX document

and adding elements into the upcoming releases to support these use cases.

11

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

SWID Tag

Description

Software Identification (SWID) Tags were designed to provide a transparent way for

organizations to track the software installed on their managed devices. It was defined by ISO in

2012 and updated as ISO/IEC 19770-2:2015 in 2015 . SWID Tag files contain descriptive

2

information about a specific release of a software product.

The SWID standard defines a lifecycle: a SWID Tag is added to an endpoint as part of the

software product’s installation process, and deleted by the product’s uninstall process. In this

lifecycle, the presence of a given SWID Tag corresponds directly to the presence of the

software product that the Tag describes. Multiple standards bodies, including the Trusted

Computing Group (TCG) and the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) use SWID Tags in

their standards.

To capture the lifecycle of a software component, the SWID specification defines four types of

SWID tags: primary, patch, corpus, and supplemental. (See Figure 3)

1. Primary Tag: A SWID Tag that identifies and describes a software product is installed

on a computing device.

2. Patch Tag: A SWID Tag that identifies and describes an installed patch which has made

incremental changes to a software product installed on a computing device.

3. Corpus Tag: A SWID Tag that identifies and describes an installable software product in

its pre-installation state. A corpus tag can be used to represent metadata about an

installation package or installer for a software product, a software update, or a patch.

4. Supplemental Tag: A SWID Tag that allows additional information to be associated with

any referenced SWID tag. This helps to ensure that SWID Primary and Patch Tags

provided by a software provider are not modified by software management tools, while

allowing these tools to provide their own software metadata.

Corpus, primary, and patch tags have similar functions in that they describe the existence

and/or presence of different types of software (e.g., software installers, software installations,

software patches), and, potentially, different states of software products. In contrast,

supplemental tags furnish additional information not contained in corpus, primary, or patch tags.

2

While ISO documents sit behind a paywall, anyone can freely use ISO-standardized specifications. See

NIST Internal Report (NISTIR) 8060: Guidelines for the Creation of Interoperable Software

Identification (SWID) Tags

for a detailed explanation and guide of SWID tags.

12

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

FIGURE 3 - The Lifecycle of software on an endpoint documented by SWID tags. Souce:

NISTIR 8060

The figure above illustrates the steps in the software lifecycle and the relationships among those

lifecycle events supported by the four types of SWID tags. Supplemental tags can be associated

with any other tag to provide additional metadata that might be of use. Taken as a body, SWID

tags can support a wide range of functions, including software discovery, configuration

management, and vulnerability management.

The following is an example of a primary SWID tag for a piece of compiled software by the

ACME Corporation called Roadrunner Detector. The tag defines the product name, version, and

other details, as well as a hash for the binary.

<SoftwareIdentity

xmlns="http://standards.iso.org/iso/19770/-2/2015/schema.xsd"

name="ACME Roadrunner Detector 2013 Coyote Edition SP1"

tagId="com.acme.rrd2013-ce-sp1-v4-1-5-0" version="4.1.5">

<Entity name="The ACME Corporation" regid="acme.com"

role="tagCreator softwareCreator"/>

<Link rel="license" href="www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.txt"/>

<Meta product="Roadrunner Detector" colloquialVersion="2013"

edition="coyote" revision="sp1"/>

<Payload>

<File name="rrdetector.exe" size="532712"

SHA256:hash="a314fc2dc663ae7a6b6bc6787594057396e6b3f569

cd50fd5ddb4d1bbafd2b6a"/>

</Payload>

</SoftwareIdentity>

13

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Use Cases

● SBOM for software components

● Continuous monitoring of installed software inventory

● Identifying vulnerable software on endpoints

● Ensuring that installed software is properly patched

● Preventing installation of unauthorized or corrupted software

● Preventing the execution of corrupted software

● Managing software entitlements

Key Features

● Provides stable software identifiers created at build time

● Standardizes software information that can be exchanged between software providers

and consumers as part of the software installation process

● Enables the correlation of information related to software including related patches or

updates, configuration settings, security policies, and vulnerability and threat advisories.

SWID tags and SBOM

SWID tags can be used as an SBOM, since they provide identifying information for a software

component, a listing of files and cryptographic hashes for the constituent artifacts that make up

a software component, and provenance information about the SBOM (tag) creator and software

component creator. Tags can explicitly link to other tags, enabling a representation of a

dependency tree.

The operational model for generating SWID tags allows the tags to be generated as part of the

build and packaging process; this allows a SWID tag-based SBOM to be produced

automatically when the related software component is packaged.

Future Directions

While SWID tags are an XML format, a more lightweight representation called CoSWID, a

Concise Binary Object Representation (CBOR)-based binary representation of SWID tag

information, is currently being standardized in the IETF to support the constrained IoT use case.

More information on CoSWID can be found below.

14

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Translation and Harmonization Guidance

Experts in SPDX and SWID engaged in a mapping exercise between the data fields in the two

formats. Not all the fields evenly mapped to each other, as the formats were originally designed

for different purposes. However, the Working Group found the potential for decent

interoperability, as enough of the fields correspond with each other. This is particularly true for

those fields related to the basic component data discussed in the Framing Group’s draft work.

Below, we lay out those basic data fields that are similar to what is described as the “Baseline

Component Information.” To illustrate this, we offer a toy example that captures many of the

features of basic SBOM in both SPDX and SWID.

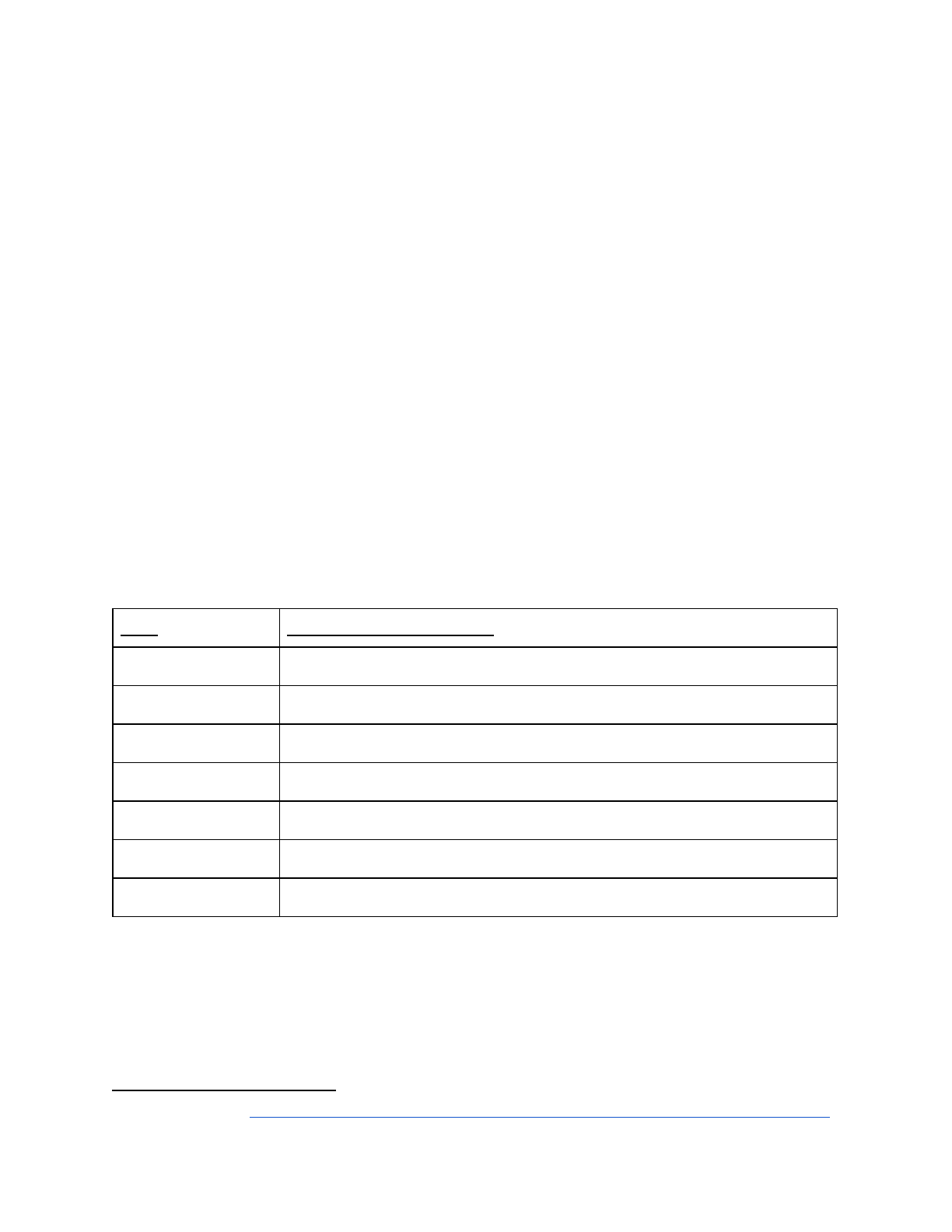

Field

Represented in SPDX

Represented in SWID

Supplier

(3.5) PackageSupplier:

<Entity> @role

(softwareCreator/publisher),

@name

Component

(3.1) PackageName:

<softwareIdentity> @name

Unique Identifier

(3.2) SPDXID:

<softwareIdentity> @tagID

Version

(3.3) PackageVersion:

<softwareIdentity> @version

Component

Hash

(3.10) PackageChecksum:

<Payload>/../<File>

@[hash-algorithm]:hash

Relationship

(7.1) Relationship:

CONTAINS

<Link>@rel, @href

SBOM Author

(2.8) Creator:

<Entity> @role (tagCreator),

@name

Table 1: A mapping between SPDX and SWID to capture the core fields discussed in the

“baseline component information” SBOM.

Example Scenario

The goal of a toy example is to demonstrate how a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) can look

in a fairly lightweight fashion. Our example, illustrated in Figure 4, Our example, illustrated in

Figure 4, focuses on an imaginary piece of software called “Application” by an organization

named Acme. Acme’s Application includes exactly two third party components, Bob’s Browser

and Bingo Buffer. Bob’s Browser, in turn, depends on third party components. We know that the

15

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Browser includes Carol’s CompressionEng, but we don’t know if the Browser includes other

components as well. Carol’s CompressionEng, in turn, is written from scratch, and we know that

it contains no third party components. Unfortunately, we don’t know if Acme’s asoftware’s other

dependency, Bingo Buffer, contains any third party dependencies.

Figure 4: A toy example of software to illustrate how an SBOM can look.

Example in SPDX

SPDXVersion: SPDX-2.1

DataLicense: CC0-1.0

DocumentNamespace: http://www.spdx.org/spdxdocs/8f141b09-1138-4fc5-aecb-fc10d9ac1eed

DocumentName: SBOM toy example

SPDXID: SPDXRef-DOCUMENT

Creator: Organization: NTIA Standards and Formats Workgroup

Created: 2019-08-31T11:29:46Z

Relationship: SPDXRef-DOCUMENT DESCRIBES SPDXRef-asoftware-v1.1

PackageName: asoftware

SPDXID: SPDXRef-asoftware-v1.1

PackageVersion: 1.1

PackageSupplier: Organization: Acme

PackageDownloadLocation: NOASSERTION

FilesAnalyzed: false

PackageChecksum: SHA1: 75068c26abbed3ad3980685bae21d7202d288317

PackageLicenseConcluded: NOASSERTION

PackageLicenseDeclared: NOASSERTION

PackageCopyrightText: NOASSERTION

Relationship: SPDXRef-asoftware-v1.1 CONTAINS SPDXRef-Browser-v2.1

Relationship: SPDXRef-asoftware-v1.1 CONTAINS SPDXRef-Buffer-v2.2

PackageName: Browser

16

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

SPDXID: SPDXRef-Browser-v2.1

PackageVersion: 2.1

PackageSupplier: Person: Bob

PackageDownloadLocation: NOASSERTION

FilesAnalyzed: false

PackageChecksum: SHA1: 94568c26abbed3ad3980685deaf1d7202d268314

PackageLicenseConcluded: Apache-2.0

PackageLicenseDeclared: NOASSERTION

PackageCopyrightText: Copyright 2019 Bob

Relationship: SPDXRef-Browser-v2.1 CONTAINS SPDXRef-CompressionEng-v3.1

PackageName: Buffer

SPDXID: SPDXRef-Buffer-v2.2

PackageVersion: 2.2

PackageSupplier: Organization: Bingo

PackageDownloadLocation: NOASSERTION

FilesAnalyzed: false

PackageChecksum: SHA1: 84568c26aabad3ad3980685beef1d7202d26831d

PackageLicenseConcluded: NOASSERTION

PackageLicenseDeclared: GPL-3.0-or-later

PackageCopyrightText: Copyright 2018 Bingo Inc.

PackageName: CompressionEng

SPDXID: SPDXRef-CompressionEng-v3.1

PackageVersion: 3.1

PackageSupplier: Person: Carol

PackageDownloadLocation: NOASSERTION

FilesAnalyzed: false

PackageChecksum: SHA1: 63568c26aebad3ad398bb85ce1f1d7202d27731a

PackageLicenseConcluded: NOASSERTION

PackageLicenseDeclared: NOASSERTION

PackageCopyrightText: NOASSERTION

Example in SWID

<SoftwareIdentity xmlns="http://standards.iso.org/iso/19770/-2/2015/schema.xsd"

name="asoftware"

tagId="acme/[email protected]"

version="1.1">

<Entity name="acme" role="tagCreator softwareCreator" />

<Link href="swid:bob/[email protected]" rel="requires" />

<Link href="swid:bingo/[email protected]" rel="requires" />

<Payload xmlns:sha512="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmlenc#sha512">

<File name="acme-asoftware-1.1.exe"

sha512:hash="BC55DEF84538898754536AE47CC907387B8F61D9ACD7D3FB8B8A624199682C8FBE6D16310

88AE6A322CDDC4252D3564655CB234D3818962B0B75C35504D55689" />

</Payload>

17

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

</SoftwareIdentity>

<SoftwareIdentity xmlns="http://standards.iso.org/iso/19770/-2/2015/schema.xsd"

name="browser"

tagId="bob/[email protected]"

version="2.1">

<Entity name="bob" role="tagCreator softwareCreator" />

<Link href="swid:carol/[email protected]" rel="requires" />

<Payload xmlns:sha512="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmlenc#sha512">

<File name="bob-browser-2.1.exe"

sha512:hash="FF4893471E763B94165CC277A9FB01D7ED66256FDDD6467D91E35AFF8F445C6312832FD97

DE1FD517606019BDC5F46E9E4E4814601E1FCB1010E90C2EBE54820" />

</Payload>

</SoftwareIdentity>

<SoftwareIdentity xmlns="http://standards.iso.org/iso/19770/-2/2015/schema.xsd"

name="buffer"

tagId="bingo/[email protected]"

version="2.2">

<Entity name="bingo" role="tagCreator softwareCreator" />

<Payload xmlns:sha512="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmlenc#sha512">

<File name="bingo-buffer-2.2.lib"

sha512:hash="AEE705CEAFDBA5EE54462443E41A447FDA69BEDCB57FC4C284D41AD67C7499A8F10C3B7D5

04A118986A3DF29564B3BD64B783C3B18BFA0F2AA4C779477A9D0D8" />

</Payload>

</SoftwareIdentity>

<SoftwareIdentity xmlns="http://standards.iso.org/iso/19770/-2/2015/schema.xsd"

name="compressionEng"

tagId="carol/[email protected]"

version="3.1">

<Entity name="carol" role="tagCreator softwareCreator" />

<Payload xmlns:sha512="http://www.w3.org/2001/04/xmlenc#sha512">

<File name="carol-compressionEng-3.1.lib"

sha512:hash="BEB0E94E089B34DADA04A53A38AE268672CA69ABB34C79E14B446D0DD5F55BE034FC9F9D7

DDF0655CDCDAB878604625805648FADA6E897541F483B2E92AE424C" />

</Payload>

</SoftwareIdentity>

18

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Future work on SBOM formats

One use case defined by the Framing Working Group is to be explicit about what is known and

unknown in the SBOM. That is, the consumer of an SBOM should have insight into when

components have no further subcomponents, versus when a component may have further

subcomponents, but no information either way is asserted by the supplier.

To date, neither SWID nor SPDX can explicitly capture and communicate this “known

unknowns” use case. Members of both support communities are looking into how the formats

can be modified to convey this information.

More broadly, tracking third party dependencies is related to a number of other key challenges

in software engineering and computer science. These challenges include:

Software Identifier challenges

In order to automatically and accurately correlate information about a single component

between multiple tools, systems or databases there is a need for a 'primary key' that

unambiguously and uniquely identifies software components. Such identity key should not

change over time and should not require a central issuing authority. There is also a need to

determine this identify key based on the software component itself when no other information is

available.

While there are some widely used approaches (such as CPE), these are not universal, and

does not meet the complete needs detailed above. There has been research to develop more

complete identifiers (e.g., Package URL and software heritage IDs), but currently they are not

widely used. More effort is required to mature these formats, and make them relevant to the

entire ecosystem. The medium term solution will probably look like a federated model with

different communities defining their own rules, and some alias databases to harmonize for

specific uses.

Tooling challenges

Broader adoption of SBOM practices will require automation, which in turn requires tools. A

broader survey of existing tools and their capabilities is essential to demonstrate and promote

production, distribution and use of SBOM data. This may require an ongoing community effort to

maintain a catalog of such SBOM tools. More research is required to catalog software package

information formats native to software development stacks, packaging tools, and software

repositories and map them to common standards.

19

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

SBOM Delivery and Distribution challenges

Free and openly available SBOM data is considered essential for enabling better supplier

selection, so consumers can compare SBOMs before purchasing a product. There is a benefit

in standardizing on a set of methods for consumers to obtain SBOMs from suppliers via

standard contact points such as [email protected] or http://example.org/sbom.

Existing standards do not make a recommendation on these methods. Data Licenses in the

SBOM itself should be considered.

Software Component Modification

Some suppliers may take a specific software component and make a particular change. This

could be done for customization, for back-porting, or further editing, curation or better support of

the code. Technically, this is fork in the code base, but since much of the original code remains,

the consumer of SBOM data may still wish to know about the underlying codebase. Changes

and remediations be documented in the standards described above. In SPDX, it is an

“annotation;” in CycloneDX it is “pedigree;” in SWID it could be represented by a “Link” to the

original source.

SBOM formats for higher trust and provenance

High security assurance systems cannot be built on assumed trust. Trust comes from being able

to independently verify what is being claimed about software components in an SBOM.

Verification of SBOM components may require tracing components as far back in the chain of

custody or prior history as possible. Standardization of information required to perform such

assessments still needs to be further studied and understood.

20

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Related Formats Surveyed

When the NTIA working group started the discussion of bill of materials, the following formats

were also suggested to be considered for identifying software. The workgroup worked with

creators of these projects to identify the key elements, and the summaries are captured below.

Links where those who are interested, can find more information are provided.

CoSWID Tag

Description:

The Concise SWID (CoSWID) tag specification is an alternate format for representing a SWID

3

tag using the Concise Binary Object Representation (CBOR). A SWID tag, expressed in XML,

can be fairly large. The size of a SWID tag can be larger than acceptable for use in constrained

devices use cases (e.g., IoT). While containing the same information as a SWID tag, CoSWID

tags reduce the size of a SWID by a significant amount. This size reduction is supported by

using integer labels in CBOR in place of human-readable strings for data elements and

commonly used values.

Use Cases

As an alternate representation of a SWID tag, CoSWID shares the same use cases as a SWID

tag. Due to the reduced size, a CoSWID tag better supports implementation of these use cases

for IoT and other constrained devices and networks.

Key Features

A CoSWID shares the same features of a SWID tag. This format reduces the footprint of a

SWID tag, while expressing the same information. The following is an example of a CoSWID

tag, in hex-based binary:

bf0f65656e2d5553207820636f6d2e61636d652e727264323031332d63652d7370312

d76342d312d352d300cc2410101783041434d4520526f616472756e6e657220446574

6563746f72203230313320436f796f74652045646974696f6e205350310d65342e312

e350e2002bf181f745468652041434d4520436f72706f726174696f6e18206861636d

652e636f6d18219f0120ffff04bf18267823687474703a2f2f7777772e676e752e6f7

2672f6c6963656e7365732f67706c2e7478741828676c6963656e7365ff05bf182d64

32303133182f66636f796f7465183473526f616472756e6e6572204465746563746f7

2183663737031ff06bf11bf18186e72726465746563746f722e657865141a200820e8

079f015820a314fc2dc663ae7a6b6bc6787594057396e6b3f569cd50fd5ddb4d1bbaf

d2b6affffffff

3

The CoSWID format is described by https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-sacm-coswid/. This IETF

draft is nearing publication as an IETF RFC.

21

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

The CoSWID in CBOR is 317 bytes in size, while the SWID tag in XML is 795 bytes in size. This

represents a 60.1% reduction in size, while expressing the same information in both tags.

The following is a more human-readable representation of the CBOR encoding of the example

CoSWID:

BF # map(*)

0F # unsigned(15)

65 # text(5)

656E2D5553 # "en-US"

20 # negative(0)

78 20 # text(32)

636F6D2E61636D652E727264323031332D63652D7370312D76342D312D352D30 #

"com.acme.rrd2013-ce-sp1-v4-1-5-0"

0C # unsigned(12)

C2 # tag(2)

41 # bytes(1)

01 # "\x01"

01 # unsigned(1)

78 30 # text(48)

41434D4520526F616472756E6E6572204465746563746F72203230313320436F796F74652045646

974696F6E20535031 # "ACME Roadrunner Detector 2013 Coyote Edition SP1"

0D # unsigned(13)

65 # text(5)

342E312E35 # "4.1.5"

0E # unsigned(14)

20 # negative(0)

02 # unsigned(2)

BF # map(*)

18 1F # unsigned(31)

74 # text(20)

5468652041434D4520436F72706F726174696F6E # "The ACME Corporation"

18 20 # unsigned(32)

68 # text(8)

61636D652E636F6D # "acme.com"

18 21 # unsigned(33)

9F # array(*)

01 # unsigned(1)

20 # negative(0)

FF # primitive(*)

FF # primitive(*)

04 # unsigned(4)

BF # map(*)

18 26 # unsigned(38)

78 23 # text(35)

22

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

687474703A2F2F7777772E676E752E6F72672F6C6963656E7365732F67706C2E747874

# "http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.txt"

18 28 # unsigned(40)

67 # text(7)

6C6963656E7365 # "license"

FF # primitive(*)

05 # unsigned(5)

BF # map(*)

18 2D # unsigned(45)

64 # text(4)

32303133 # "2013"

18 2F # unsigned(47)

66 # text(6)

636F796F7465 # "coyote"

18 34 # unsigned(52)

73 # text(19)

526F616472756E6E6572204465746563746F72 # "Roadrunner Detector"

18 36 # unsigned(54)

63 # text(3)

737031 # "sp1"

FF # primitive(*)

06 # unsigned(6)

BF # map(*)

11 # unsigned(17)

BF # map(*)

18 18 # unsigned(24)

6E # text(14)

72726465746563746F722E657865 # "rrdetector.exe"

14 # unsigned(20)

1A 200820E8 # unsigned(537403624)

07 # unsigned(7)

9F # array(*)

01 # unsigned(1)

58 20 # bytes(32)

A314FC2DC663AE7A6B6BC6787594057396E6B3F569CD50FD5DDB4D1BBAFD2B6A

#

"\xA3\x14\xFC-\xC6c\xAEzkk\xC6xu\x94\x05s\x96\xE6\xB3\xF5i\xCDP\xFD]\xDBM\e\xBA

\xFD+j"

FF # primitive(*)

FF # primitive(*)

FF # primitive(*)

FF # primitive(*)

23

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

CPE

A related data format is the Common Platform Enumeration (CPE ). This format is “a

4

standardized method of describing and identifying classes of applications, operating systems,

and hardware devices present among an enterprise's computing assets”. The CPE is used in

various situations such as the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). CPE enables

identification of specific applications, with or without version numbers, but does not by itself

identify subcomponents.

CycloneDX

CycloneDX is a lightweight SBOM specification designed specifically for software security

requirements and related risk analysis. The specification is written in XML with JSON in

development. It’s designed to be flexible, easily adoptable, with implementations for popular

build systems. The specification encourages use of ecosystem-native naming conventions,

supports SPDX license IDs and expressions, pedigree, and external references. It also natively

supports the Package URL specification and correlating components to CPEs.

The project is open source, Apache 2.0 licensed, and encourages the development of schema

extensions to enhance it’s base capabilities.

Field

Represented in CycloneDX

Supplier

publisher

Component

name

Unique Identifier

bom/serialNumber and component/bom-ref

Version

version

Component Hash

hash

Relationship

(Nested assembly/subassembly and/or dependency graphs)

SBOM Author

bom-descriptor:metadata/manufacture/contact

Example in CycloneDX

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<bom serialNumber="urn:uuid:3e671687-395b-41f5-a30f-a58921a69b71" version="1"

xmlns="http://cyclonedx.org/schema/bom/1.1"

xmlns:dg="http://cyclonedx.org/schema/ext/dependency-graph/1.0"

4

CPE is defined in https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/security-content-automation-protocol/specifications/cpe/

24

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

xmlns:bd="http://cyclonedx.org/schema/ext/bom-descriptor/0.9">

<components>

<component type="library" bom-ref="pkg:maven/org.bob/[email protected]">

<publisher>Bob</publisher>

<group>org.bob</group>

<name>browser</name>

<version>2.1</version>

<hashes>

<hash alg="SHA-1">94568c26abbed3ad3980685deaf1d7202d268314</hash>

</hashes>

<cpe>cpe:2.3:a:bob:browser:2.1:*:*:*:*:*:*:*</cpe>

<purl>pkg:maven/org.bob/[email protected]</purl>

</component>

<component type="library" bom-ref="pkg:maven/org.carol/[email protected]">

<publisher>Carol</publisher>

<group>org.carol</group>

<name>CompressionEng</name>

<version>3.1</version>

<hashes>

<hash alg="SHA-1">63568c26aebad3ad398bb85ce1f1d7202d27731a</hash>

</hashes>

<cpe>cpe:2.3:a:carol:compression_eng:3.1:*:*:*:*:*:*:*</cpe>

<purl>pkg:maven/org.carol/[email protected]</purl>

</component>

<component type="library" bom-ref="pkg:maven/org.bingo/[email protected]">

<publisher>Bingo</publisher>

<group>org.bingo</group>

<name>Buffer</name>

<version>2.2</version>

<hashes>

<hash alg="SHA-1">84568c26aabad3ad3980685beef1d7202d26831d</hash>

</hashes>

<cpe>cpe:2.3:a:bingo:buffer:2.2:*:*:*:*:*:*:*</cpe>

<purl>pkg:maven/org.bingo/[email protected]</purl>

</component>

</components>

<bd:metadata>

<bd:softwareName>asoftware</bd:softwareName>

<bd:softwareVersion>1.1</bd:softwareVersion>

<bd:hashes>

<hash alg="SHA-1">75068c26abbed3ad3980685bae21d7202d288317</hash>

</bd:hashes>

<bd:cpe>cpe:2.3:a:acme:asoftware:2.1:*:*:*:*:*:*:*</bd:cpe>

<bd:manufacture>

<bd:name>Acme</bd:name>

</bd:manufacture>

</bd:metadata>

<dg:dependencies>

<dg:dependency ref="pkg:maven/org.bob/[email protected]">

25

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

<dg:dependency ref="pkg:maven/org.carol/[email protected]"/>

</dg:dependency>

<dg:dependency ref="pkg:maven/org.bingo/[email protected]"/>

</dg:dependencies>

</bom>

Grafeas

Grafeas is an open artifact metadata API to audit and govern your software supply chain. It

provides a common language to store, retrieve, and query metadata on software artifacts. By

supporting metadata for common use-cases, it aims to provide streamlined composability and

portability for artifact metadata.

Metadata is grouped into two types: notes and occurrences. Notes are created by metadata

provider in provider’s project and contains context-insensitive metadata relevant to linked

occurrences. Occurrences are created by in customer’s project and link to provider notes. To

illustrate how notes and occurrences work together, consider a vulnerability (CVE). When a

CVE is created, it is recorded as a note by a metadata provider. If a CVE applies to a particular

artifact, an occurrence is generated. In a similar manner, notes and occurrences are generated

and applied to record the following types of metadata: package, builds, images, attestations,

and deployments.

in-toto

Description:

in-toto is a framework to cryptographically secure the broader software supply chain. To do so, it

allows actors to create cryptographically-verifiable pedigree and provenance information for

artifacts as they flow throughout the chain. In the context of a Software Bill of Materials, in-toto

link metadata (i.e., signed attestations) allow parties to create a certificate of the software

artifact that can be shared with consumers.

in-toto link metadata files have a very flexible format, that can be as descriptive as needed. An

in-toto link contains the following fields:

Field Name

Description

Example

Mandatory?

name

An arbitrary identifier for this

certificate.

“build-gcc”

Yes

command

Information about the command

that created this certificate.

“gcc -c foo.c”

No

Materials

A list of artifacts consumed when

creating this software and their

checksum

“foo.c: {sha256: ….}”

No

26

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Products

a list of artifacts produced and their

checksum

“foo: {sha256: …}”

No

Byproducts

Information produced during the

creation of products

{“return-value” 0,

“stderr”: “”}

No

Environment

Any relevant environment

information such as environment

variables, system time, host

integrity checks, etc.

{“LANG=en_US-UTF8”}

No

Signature

A cryptographic signature over the

the previous fields.

{

"keyid": "12c55….",

"method":

"RSASSA-PSS",

"sig":

"a0d3237a52..."

}

Yes

in-toto has been successfully deployed in a myriad of environments, from large-scale cloud

monitoring providers such as Datadog, to widely-adopted open source projects such as Debian.

Package-URL (purl)

Description:

A package URL (purl) is an attempt to standardize existing approaches to reliably identify and

locate software packages. A purl is a URL string used to identify and locate a software package

in a mostly universal and uniform way across programming languages, package managers,

packaging conventions, tools, APIs, and databases. Such a package URL is useful to reliably

reference the same software package using a simple and expressive syntax and conventions

based on familiar URLs.

A purl is a URL composed of seven components:

scheme:type/namespace/name@version?qualifiers#subpath

Components are separated by a specific character for unambiguous parsing.

Component

Definition

Usage

scheme

This is the URL scheme with the constant value of "pkg". One

of the primary reasons for this single scheme is to facilitate

the future official registration of the "pkg" scheme for package

URLs.

Required

27

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

type

The package "type" or package "protocol" such as maven,

npm, nuget, gem, pypi, etc.

Required

namespace

Some name prefix such as a Maven groupid, a Docker image

owner, a GitHub user or organization.

Optional and

type-specific

name

The name of the package.

Required

version

The version of the package.

Optional

qualifiers

Extra qualifying data for a package such as an OS,

architecture, a distro, etc.

Optional and

type-specific

subpath

Extra subpath within a package, relative to the package root.

Optional

Components are designed such that they can form a hierarchy, from the most significant

component on the left, to the least significant components on the right.

A purl must NOT contain a URL Authority; i.e. there is no support for username, password, host

and port components. A namespace segment may sometimes look like a host, but its

interpretation is specific to a type.

Examples

pkg:deb/debian/curl@7.50.3-1?arch=i386&distro=jessie

pkg:docker/gcr.io/customer/dockerimage@sha256:244fd47e07d1004f0aed9c

pkg:gem/ruby-advisory-db-check@0.12.4

pkg:golang/google.golang.org/genproto#googleapis/api/annotations

pkg:maven/org.apache.xmlgraphics/batik-anim@1.9.1?packaging=sources

Information above was extracted from: https://github.com/package-url/purl-spec

Linkage

SPDX: Next version of the specification (2.2) will formally recognize PURL’s as valid External

References <type>, and can be captured today via <type> of OTHER.

SWID: A PURL can be provided in a SWID tag using the “link” element.

SEVA

SEVA (Software EVidence Archive) is a hardened XML SBOM format developed and

maintained by Ion Channel, primarily for high assurance systems in critical infrastructure that

must be maintained on discontiguous networks. SEVA is engineered for transfer of signed

assurance data across one-way data guards in an auditable fashion, to maintain continuity of

assurance for components and applications running on networks that are not connected to the

Internet. Because SEVA is implemented as a NIEM-compliant (https://www.niem.gov/) format,

the format can be externally verified and extended or restricted in a verifiable manner.

28

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

Linkage: SPDX is working with Ion Channel to include the SEVA information for documenting

security use cases to the next version of the specification (2.2).

Software Heritage Index

Description:

Software Heritage is a non profit initiative actively supported by a large number of organizations

—software, systems and tool vendors, IT users, academic and governmental institutions. It is

building a universal archive of software source code, as a common infrastructure catering to a

variety of use cases from industry to science and culture.

Use Cases:

One of the use cases specifically listed on their mission statement is source code tracking for

industry: “Because industry cannot afford to lose track of any part of its source code, we track

software origin, history, and evolution. Software Heritage will provide

unique software

identifiers, intrinsically bound to software components

, ensuring persistent traceability

across future development and organizational changes.

”

These intrinsic identifiers are based on cryptographic signatures, have a precise formal

definition and are already available for the more than 10 billions of artefacts stored in the

Software Heritage archive. They are an essential building block for ensuring integrity of a

source code base, and are currently being used by some major industry players to implement a

part of their SBOM workflow, related to source code distribution obligations, as well as from the

Wikidata community.

Linkage

SPDX: Next version of the specification (2.2) will formally recognize SWH IDs as valid External

References <type>, and can be captured today via <type> of OTHER.

SParts

Description:

The Software Parts (SParts) project delivers a hyperledger, based on Sawtooth, that enables

determination of the chain of custody of all the software parts from which a product (e.g., IoT

device) is comprised of. The ledger provides both access to and accountability for software

meta information of software parts exchanged among manufacturing supply chain participants.

A software part is any software component that could be represented as one or more files. (e.g.,

source code, binary library, application, an operating system runtime, container, ...).

Use Cases:

An envelope of information can be used to summarize pedigree and provenance of software

through multiple hops in the supply chain. An envelope can contain SPDX, SWID and other

SBOM information. Participants pass these envelopes from producer to consumer throughout

the supply chain adding in the metadata for their contributions to the envelopes.

29

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

SPDX-Lite

Description:

SPDX-Lite is a profile for a set of existing SDPX fields that the OpenChain Project Working

group is recommending be used when collecting data via spreadsheets from organizations that

do not have sophisticated tracking of software provenance in place. As the fields form a valid

SPDX-document, the translation tools can be applied to turn the spreadsheet into other

machine readable formats.

This subset has been agreed to be documented and adopted as an official profile, into the

SPDX 2.2 specification as an Appendix.

Use Cases:

A spreadsheet containing the SPDX-Lite profile fields can be requested by companies from their

suppliers who are hardware companies and unfamiliar with software and open source software

licensing.

30

Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards - Version 20191025

About the authors of this document

This document was drafted by an open working group convened by the National

Telecommunications and Information Administration in a multistakeholder process, including the

following individuals and organizations: Chris Clark (Synopsys), Robin Gandhi (University of

Nebraska at Omaha), Christopher Gates (Velentium), Art Manion (CERT Coordination Center),

Bob Martin (MITRE), Chandan Nandakumaraiah (Juniper Networks), Brendan O’Connor

(GitHub), Kate Stewart (Linux Foundation), JC Herz (Ion Channel), Tim Walsh (Mayo), David

Waltermire (NIST), Steve Springett (OWASP)

Others participated, but do not wish to be named.

31