DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT A: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC POLICY

ENVIRONMENT, PUBLIC HEALTH AND FOOD SAFETY

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects,

national practices and recommendations

for future successful approach

Study

Abstract

Available information on the implementation of the ELV Directive suggests that

there is still room for improvement regarding management of end-of-life

vehicles in Europe. The study evaluates and discusses fundamental aspects of

ELV management such as arisings, legal and illegal shipment, de-pollution and

recycling & recovery of end-of-life vehicles. Existing problems are described and

recommendations for improvements of the practical implementation are given.

IP/A/ENVI/ST/2010-07 October 2010

PE 447.507 EN

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Environment,

Public Health and Food Safety.

AUTHORS (all Umweltbundesamt GmbH)

Jürgen Schneider (Reviewer and Project Leader)

Brigitte Karigl (Task Manager)

Christian Neubauer

Maria Tesar

Judith Oliva

Brigitte Read (Proofreader)

RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR

Mr Lorenzo Vicario

Policy Department A

Economic and Scientific Policy

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

E-mail:

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: [EN]

ABOUT THE EDITOR

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to: Poldep-

________

Manuscript completed in October 2010.

Brussels, © European Parliament, 2010.

This document is available on the Internet at:

________

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do

not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorized, provided the

source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Contents

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 5

LIST OF TABLES 6

LIST OF FIGURES 7

Executive summary 8

Executive summary 8

General information 15

1. Arising of ELVs 17

1.1. Legal background 17

1.2. Results 17

1.2.1. Automotive market 18

1.2.2. Statistics on ELVs 19

1.2.3. Statistics on used cars 20

1.3. Steps taken by the Commission Services to overcome problems 22

1.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 24

2. Concept of vehicle de-registration 25

2.1. Legal background 25

2.2. Results 26

2.2.1. Implementation of Article 5 (3) according to MS reporting 27

2.2.2. Additional information on the implementation of Article 5(3) 28

2.3. Steps taken by Commission Services to overcome problems 31

2.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 32

3. Legal and illegal shipment of ELVs 33

3.1. Legal background 33

3.2. Results 35

3.2.1. Legal shipment of ELVs and parts thereof 35

3.2.2. Shipment of second-hand cars 37

3.2.3. Illegal shipment of end-of life vehicles 42

3.3. Steps taken by Commission Services to overcome problems 43

3.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 45

4. De-pollution of ELVs 46

4.1. Legal background 46

4.2. Results 47

3

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

4.2.1. Materials removed from ELVs as reported by Member States 47

4.2.2. Removal of individual materials/components containing hazardous

substances 49

4.2.3. ELV-treatment facilities in Member States 52

4.2.4. Inspections of ELV treatment facilities 54

4.2.5. Contamination of shredder residues 54

4.3. Steps taken by Commission Services to overcome problems 55

4.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 55

5. Recycling and recovery of ELVs 56

5.1. Legal background 56

5.2. Results 56

5.2.1. Recycling and recovery rates achieved by the Member States 56

5.2.2. Recycling of materials crucial for achievement of the targets 60

5.3. Steps taken by Commission Services to overcome problems 65

5.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 65

6. Producer responsibility 67

6.1. Legal background 67

6.2. Results 68

6.2.1. Limitation of the use of hazardous substances 68

6.2.2. Systems for the collection of ELVs 68

6.2.3. Coding standards and information on dismantling 69

6.2.4. Vehicle design and the environmental sound management 69

6.3. Steps taken by Commission Services to overcome problems 69

6.4. Conclusions & Recommendations 70

References 71

Annex 74

4

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ACEA European Automobile Manufacturers Association

ATF Autorized treatment facility

Category

M1

Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers and

comprising no more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat

Category

N1

Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of goods and having a

maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tonnes (according to Directive

70/156/EEC)

CoD Certificate of Destruction

DIV Dienst Inschrijving Voertuigen

DVLA Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency

EES Electrical & Electronic System

ELV End-of-life vehicle

EReg European Vehicle and Driver Registration Authorities

EUCARIS European Car and Driving Licence Information System

IDIS International Dismantling Information System

LGT Liquified gas tank

TFS Transfrontier Shipment

WSR Waste Shipment Regulation

5

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1

Problems and recommendations for successful approaches in the future 13

Table 2

Production of passenger cars in Europe 19

Table 3

Comparison of the numbers of ELVs and de-registered cars 20

Table 4

Classifications of vehicles and parts thereof 34

Table 5

End-of-life vehicles and parts thereof exported for further treatment. 36

Table 6

Exports of used cars in units 38

Table 7

Exports of used vehicles out of the EU in 2008 40

Table 8

Destinations of exported used cars in Africa in 2008 41

Table 9

Average price of imported used cars (exports from the EU) in 2008 41

Table 10

Removal of fluids from ELV in Belgium in 2009 as reported by FEBELAUTO 50

Table 11

Authorized ELV-treatment facilities 53

6

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Development of the passenger car fleet and the ELV arisings 2007-2008 ......... 21

Figure 2 : Export of used cars between and out of the EU-27 (in units) ......................... 39

Figure 3 : Main destinations for used cars out of the EU-27 in 2008 (in units) ................ 40

Figure 4 : End of life vehicle or second-hand car? ...................................................... 43

Figure 5 : Removal of starter batteries from ELV 2008................................................ 48

Figure 6 : Removal of liquids (excluding fuels) from ELVs............................................ 48

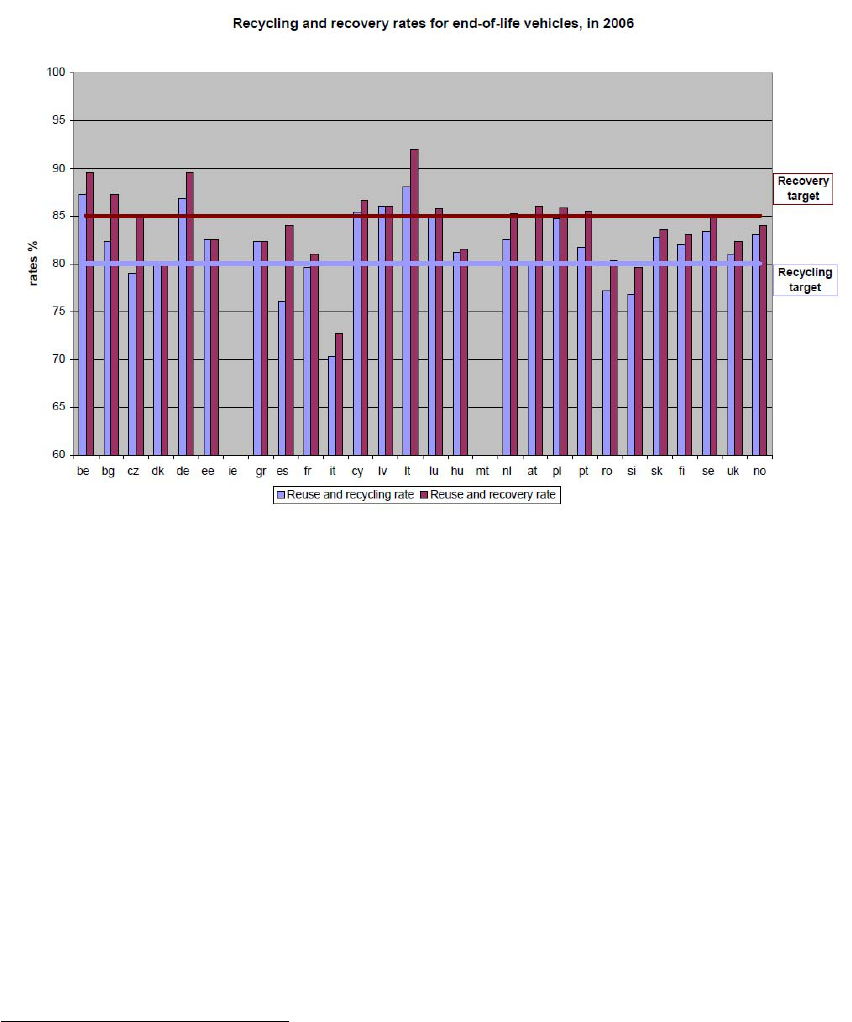

Figure 7 : Recycling and recovery rates reported by the Member States for the reference

year 2006...................................................................................................... 57

Figure 8 : Recycling and recovery rates reported by the Member States for the reference

year 2007...................................................................................................... 58

Figure 9 : Recycling and recovery rates reported by the Member States for the reference

year 2008...................................................................................................... 58

Figure 10 : Removal and Reuse & Recycling of large plastic parts in the course of ELV

treatment in 2008........................................................................................... 61

Figure 11 : Removal and Reuse & Recycling of tyres in the course of ELV treatment in 2008

.................................................................................................................... 62

Figure 12 : Removal and Reuse & Recycling of glass in the course of ELV treatment in 2008

.................................................................................................................... 63

7

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Directive 2000/53/EC on end-of life vehicles (ELV Directive), was published in the Official

Journal L269 on 21st October 2000. The main objectives include a) to make vehicle

dismantling and recycling more environmentally friendly, b) to set clear quantified targets

for reuse, recycling and recovery of vehicles and their components and c) to encourage

producers to manufacture new vehicles also with a view to their recyclability.

Up to now two implementation reports have been published, based on questionnaires

completed by Member States pursuant to Commission Decision 2001/753/EC. The reports

provide information on the transposition of Directive 2000/53/EC into national law and on

the practical implementation. The first report covers the period 2002-2005

(COM/2007/0618 final), the second the period 2005-2008 (COM/2009/0635 final). In

addition, annual data on the achievement of the targets for reuse/recycling and

reuse/recovery, which had to be reported under Commission Decision 2005/293/EC were

published by Eurostat (for the reference years 2006, 2007 and 2008 up to now).

There is evidence to suggest that some of the provisions of the Directive have not yet been

transposed fully or correctly, which is also indicated by the number of infringement cases

(in 2009, nine non-conformity cases and six cases for non-reporting were still pending).

1

Moreover, several problems regarding the implementation of the provisions of the ELV

Directive in practice, which are not always reflected in the official statistics, were identified.

This study evaluates and discusses fundamental aspects of end-of-life vehicle management

in Europe, describes existing problems and gives recommendations for improvements of

the practical implementation of the ELV Directive in Europe.

End-of-life vehicles arisings

The European Environment Agency estimated the number of end-of-life vehicles arising in

the EU-25 to be about 14 million in 2010, compared to 12.7 million in 2005

2

. This is a

number that differs significantly from the 6.2 million end-of-life vehicles in 2008 as

published by Eurostat and based on data reported by 24 Member States

3

.

Furthermore, there are gaps between the numbers of de-registered passenger cars and

end-of-life vehicles in many Member States. In most Member States the number of ELVs

represents more than 50% of the amount of de-registered passenger cars (e.g. Belgium,

Italy, Spain and the Netherlands). Thus, for those countries the gap between the number of

de-registered cars and ELVs is lower than 50%. In other Member States (e.g. Austria,

Denmark, Finland, Sweden) the gap is higher, and there is no detailed information available

on the further use of more than 50% of the de-registered cars.

A certain number of de-registered passenger vehicles are commercially exported as

second-hand cars. According to the COMEXT database, the official European Foreign Trade

Statistics, about 893,000 used cars were exported out of the EU by Member States in 2008.

1

European Commission (2009): Report on the Implementation of Directive 2000/53/EC on End-of-Life-Vehicles for

the period 2005-2008

2

ETC/RWM 2008: Projection of end-of-life vehicles (prepared for the European Environment Agency (EEA) under

its 2007 work programme as a contribution to the EEA's work on waste outlooks)

3

Eurostat (available at : http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/waste/data/wastestreams/elvs)

8

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

The remaining gap can be accounted for by private exports of used cars (not registered in

COMEXT), illegal shipment of end-of-life vehicles (see paragraph below), illegal disposal

and by vehicles kept in garages in the country of de-registration.

To analyse the remaining gap and to find out if all end-of-life vehicles are accounted for, it

is crucial to differentiate between ELVs and used cars. The question of when a used car

ceases to be product and becomes waste according to the Waste Framework Directive

(2008/98/EC) is answered in different ways across EU Member States. As a consequence,

there are problems regarding the comparability of the reported data and in individual cases

regarding the answer to the question if a transboundary shipment of a vehicle is subject to

the provisions of the Waste Shipment Regulation No 1013/2006.

In order to analyse the gaps between reported figures on de-registered cars and the arising

on end-of-life vehicles it is necessary to have available data on the national vehicle

markets. However, this information is not yet available consistently for European Member

States. First steps to gather these data have been taken: The guidance document on “How

to report on end-of-life vehicles according to Commission Decision 2005/293/EC” (Draft

version, 20th April 2010) aims to enhance the quality of data on the national vehicle

market by Member States reportings (including the number of finally de-registered vehicles

and the number of exports of used vehicles).

In general, data quality and data availability on the national vehicle markets (including data

on de-registration of cars, import/export of used cars) should be improved, e.g. by

involving the Association of European Vehicle and Driver Registration Authorities (EReg)

and/or the European Car and Driving Licence Information System (EUCARIS).

Vehicle de-registration

There are different approaches to the de-registration of vehicles across European Member

States. In some countries (e.g. in Austria) a vehicle is de-registered as a rule with the

change of ownership of a car. In other countries (e.g. in the UK) vehicles are not de-

registered when ownership changes. In these countries, de-registration generally takes

place when the car owner wants to dispose of the vehicle. De-registered vehicles may be

re-registered and put back on the road only under exceptional circumstances and if prior

approval has been granted.

When a vehicle has become waste (end-of-life vehicle) additional requirements for de-

registration have to be met. Article 5 (3) of the ELV Directive requires Member States to set

up a system according to which the presentation of a certificate of destruction (CoD) is a

condition for de-registration of the end-of life vehicle. In 2009, twenty-one Member States

reported that they had implemented the condition to present a CoD for de-registering an

ELV

1

.

In some Member States (e.g. Austria, Finland) the number of issued CoDs is not equal to

the arisings of end-of-life vehicles. This might be due to the fact that a vehicle can be de-

registered before the car owner decides that his/her car becomes waste and thus an end-

of-life vehicle. There is an information gap regarding the whereabouts of de-registered

vehicles. To close this gap, information on the further use of a vehicle should be obtained

its de-registration (e.g. in the form of a declaration that there is no intention to dispose of

the vehicle, and stating whether the car owner intends to sell or export the vehicle or keep

it in a garage).

9

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

To obtain more information on the whereabouts of vehicles on national markets the

Eurostat guidance document on “How to report on end-of-life vehicles according to

Commission Decision 2005/293/EC” suggests reporting the number of CoDs issued and the

numbers of final de-registrations per year. Member States should report the data as

suggested in the guidance document; this will allow better assessments as to whether full

implementation of Article 5 (3) has been achieved in practice.

Shipment of end-of-life vehicles

Compared to the arisings of end-of-life vehicles, the numbers of end-of-life vehicles that

are exported are low. According to data reported by 22 Member States in 2008, 260,000

tonnes of end-of-life vehicles and parts thereof were exported, which is an increase

compared to the reference year 2006 when these exports amounted to 88,000 tonnes

(data available for 19 Member States)

4

.

A considerable number of vehicles which are de-registered in the Member States are

exported as used cars. According to data from the COMEXT database (the official European

Foreign Trade Statistics

5

) the number of used cars shipped within the EU is slightly lower

(746,000 in 2006; 794,000 in 2008) than the number exported out of the EU (900,000 in

2006; 893,000 in 2008)

Furthermore there is evidence suggesting that considerable numbers of ELVs are exported

illegally from European Member States; predominantly to Africa and the Middle Eastern

countries. This is supported by several press reports as well as by the results of joint

activity inspections in the framework of an IMPEL-TFS project completed in 2008, where

several cases of illegal shipment of end-of-life vehicles were reported – mostly to African

countries

6

.

In countries with low average income in some European regions as well as outside the EU

there is a market for very cheap cars, often in bad condition or serving as a source of spare

parts. An important motive for illegal shipments of end-of-life vehicles is that the owner of

an old vehicle can make some profit (usually a few hundred Euros) when selling it to a car

dealer who ships it abroad, whereas there is usually no money to be made from disposing

of an ELV in the country of de-registration.

Effective action against illegal shipments of end-of-life vehicles is hampered by the fact that

there are differences in the interpretation of end-of-life vehicles and used cars, and the

distinction between them, in different countries. To address this problem the

Correspondents’ Guidelines No 9 (draft status), which outlines how the Waste Shipment

Regulation should be interpreted by all Member States, provides guidance on the distinction

between an end-of-life vehicle and a used car.

To reduce illegal shipments of end-of-life vehicles, inspections of transports within and out

of the EU should be intensified. Binding rules regarding the differentiation between end-of-

life vehicles and used cars at a European level would facilitate effective action against

illegal shipments of end-of-life vehicles.

4

Eurostat (available at : http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/waste/data/wastestreams/elvs)

5

http://www.fiw.ac.at/index.php?id=367

6

IMPEL-TFS End of Life Vehicles 2008: Vehicles for export Project ; Final report September 2008

10

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Furthermore, measures which make the disposal of an old vehicle in the country of de-

registration more attractive - such as refunds obtained in a deposit-refund system - would

help reduce illegal shipments of end-of-life vehicles.

De-pollution

Regarding de-pollution of end-of-life vehicles in Europe, two main aspects have to be

considered.

First, there is evidence suggesting that end-of-life vehicles are treated illegally in some

cases. However, the situation seems to be improving. This can also be seen from the fact

that, compared to 2005, the numbers of authorised treatment facilities have increased

significantly in some Member States (UK, BE, GR) in recent years.

Second, there is evidence suggesting that even in authorised treatment facilities de-

pollution is not in full compliance with the relevant requirements of the ELV Directive.

Liquids seem to be removed to a certain extent. Certain types of fluids or components such

as brake fluids, windscreen washer fluid, oil filters or shock absorbers, however, are not

always removed or de-polluted.

Usually little effort is put into the removal of components containing heavy metals, such as

Hg-containing display backlights or switches.

Lead-acid batteries are generally removed from end-of-life vehicles because lead may be

used as a source of income and because of constraints for the shredder-process if not

removed. Liquefied gas tanks and air bags are usually removed because of the well-known

risks for shredder plants.

In order to improve de-pollution of end-of-life vehicles, measures should be taken against

illegal waste car dismantlers and unauthorised treatment facilities (e.g. by stepping up

inspections by competent authorities in the Member States). Inspections of ELV treatment

plants should address the effectiveness of de-pollution adequately.

De-pollution of ELVs should lead to shredder residues with low contents of hazardous

substances. According to some available information on the composition of shredder

residues, it is in particular the content of hydrocarbons that indicates that the de-pollution

of end-of-life vehicles is not always sufficient. Comprehensive assessments of the quality of

ELV shredder residues at European level are recommended and would allow conclusions

about the effectiveness of the de-pollution of end-of-life vehicles.

Recycling and recovery

According to data published by Eurostat in 2008, 20 Member States achieved the

reuse/recycling target of 80% of the average ELV weight. Sixteen Member States met the

85% reuse/recovery target.

11

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

However, the reported recycling and recovery rates are not always comparable and might

be overestimated. This is due to the following reasons:

The classification of technically identical treatment operations such as recycling,

recovery or disposal differs between Member States due to different national

interpretations. Backfilling, landfill construction and landfill cover, use of plastics in

blast furnaces are often considered differently in different Member States

Member States gather data in different ways and at different time intervals (e. g.

data on the quality & frequency of ELV treatment trials) and different methodologies

are applied for the calculation of recycling and recovery rates (e.g. how much of the

whole ELV treatment chain is considered)

The above factors can significantly influence the achievement of recycling and recovery

targets.

Evidence suggests that there is still room for improvement regarding the recycling and

recovery of ELV materials. Dismantling and subsequent material recycling of glass and

plastics for instance takes place in minor quantities in several Member States. Recovery of

glass after shredding, however, prevents glass recycling because of the bad quality of the

glass. Recovery of plastics from shredder residues is still limited to only a few Member

States. Whereas in some Member States post-shredder technology has been installed and

landfilling of shredder residues prohibited or made very expensive, several Member States

still deposit shredder residues on landfills.

To improve the comparability of recycling and recovery rates and to avoid market

distortions within the waste treatment industry, there is a need for binding rules for the

classification of particular treatment operations as “recycling”, “recovery” or “disposal”

across the EU. Furthermore, the harmonisation of data collections and the methodologies

applied for the calculation of recycling and recovery rates - as already mentioned by an

expert working group set up by the European Commission and Eurostat - is recommended.

In order to achieve an environmentally sound treatment of end-of-life vehicles it would be

useful, in addition to the overall recycling and recovery targets, to establish specific

treatment obligations for particular material streams, taking into account their overall

environmental impact.

Producer responsibility

Producers and manufacturers have taken the necessary measures to ban certain hazardous

substances (Cd, Hg, Pb, and CrVI) in new cars as required by Article 4 of the ELV Directive.

There is no evidence suggesting that these requirements are not fulfilled. Nevertheless, and

considering that no external monitoring is conducted, it seems to be important to assess

the overall effect of the ban in practice at European level.

For providing information on the dismantling of cars as required under Article 8 of the ELV

Directive, manufacturers generally use an international platform, the so-called IDIS system

(International Dismantling Information System). However, the use of this information is not

common practice in ELV treatment plants. The transfer of information about the

dismantling of vehicles should be encouraged in order to promote the correct and

environmentally sound treatment of end-of-life vehicles.

12

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Problems identified in end-of-life vehicle management in Europe and need for

action to achieve the aims of the ELV Directive

Table 1: Problems and recommendations for successful approaches in the future

Problem

Recommendation regarding

need for action

Responsi-

bility

Addressing

Legislative Options Other options

Intensify MS

inspections of

transports within

and out of the EU

Member States

/ European

Commission

Lay down minimum

requirements regarding the

frequency of spot checks on

shipments of waste

Regulation 2006/1013/EC

when revised (Article 50)

Oblige MS to monitor

shipments of ELVs

Directive 2000/53/EC when

revised

(compare proposal (2008)

for the recast of the WEEE-

Directive, Article 20, Annex

I)

Promote joint

enforcement

projects, promote

exchange of

knowledge, best

practices under

IMPEL (Cluster 2)

Support action

against illegal

shipments by

establishing binding

rules for the

distinction between

ELVs / used cars

European

Commission

Make mandatory the

relevant contents of the

Draft Correspondent’s

guidelines No 9 according

to Regulation

2006/1013/EC Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

Illegal

Shipment of

ELVs

Illegal

activity

Introduce incentives

for the disposal of

cars in the country

of de-registration

(e.g. by deposit-

refund systems)

Member States

/ European

Commission

To commission a

study on the impact

of incentives for

disposal of ELVs in

the country of

deregistration

Commission

Services

Different

national

interpretations

of ELVs and

used cars,

differences in

the distinction

between

them.

Member

States

Establish binding

rules at European

level for the

distinction between

ELVs and used

vehicles

European

Commission

Make mandatory the

relevant contents of the

Draft Correspondent’s

guidelines No 9 according

to Regulation

2006/1013/EC Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

Lack of

comparable

data on the de-

registration of

used cars for

all Member

States (e.g. on

the further use

of de-registered

cars)

Member

States

Request information

on the fate of a

vehicle when de-

registering it

Request data on

national vehicle

markets (including

on further use of de-

registered cars).

European

Commission

Oblige MS to request

information on the fate of

vehicles when they are de-

registered Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

(Article 5)

Oblige MS to report on the

fate of deregistered

vehicles Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

(Article 7), Decision

2005/293/EC when revised

(Article 1 (3))

13

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Problem

Recommendation regarding

need for action

Legislative Options Other options

Responsi- Addressing

bility

Cases of illegal

treatment of

ELVs still exist

Illegal

activity

Take measures

against illegal car

dismantlers and

unauthorised

treatment facilities

(e.g. stepping up

inspections)

Member States

Strengthen

activities related to

training and

exchange of

experiences,

comparison,

evaluation and

development of

good practices, etc.

under IMPEL

(Cluster 1)

Address the

effectiveness of de-

pollution adequately

in the course of

inspections at ELV

treatment facilities.

Member States

/ European

Commission

Establish more detailed

minimum technical

treatment requirements for

ELVs Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

(Article 6, Annex I)

Strengthen

activities related to

training and

exchange of

experiences,

comparison,

evaluation and

development of

good practices, etc.

under IMPEL

(Cluster 1)

Indication that

ELVs are not

always de-

polluted

properly

(although little

information is

available)

Illegal

activity

Comprehensive

evaluation of the

quality of ELV

shredder residues

European

Commission

To commission a

study on the actual

effects of de-

pollution of ELVs on

ELV shredder

residues

Commission

Services

Provision of

sufficient capacity of

environmentally

sound

recycling/recovery

operations

Member States

Considerable

amounts of

ELV materials

are still

disposed of

(not all MS

have achieved

the

recycling/recov

ery targets).

Lack of

comparability;

evidence

suggesting that

the reported

recycling/rec

overy rates

are

overestimated

Member

States

Establish binding

rules for the

classification of

treatment

operations for

“recycling”/”recover

y”/”disposal”, data

gathering and

calculation

methodology

European

Commission

Establish binding rules for

the classification of

particular treatment

operations Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

(Article 7)

Make mandatory the

relevant contents of the

Eurostat guidance

document on “How to

report on end-of-life

vehicles according to

Commission Decision

2005/293/EC” Directive

2000/53/EC when revised

(Article 7), Decision

2005/293/EC when revised

14

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

GENERAL INFORMATION

EU legislation on End of Life Vehicles (ELVs) is still not fully implemented in some Member

States. The European Commission has worked on the subject and an oral question relating

to the issue of ELVs has been raised by MEP Davies in the ENVI Committee of the European

Parliament.This question has been taken up by the Coordinators of the ENVI Committee,

who requested a study on "End of life vehicles: legal aspects, national practices and

recommendations for future successful approach". Umweltbundesamt GmbH has been

contracted to prepare this study as part of the Framework Contract ‘External expertise on

emerging regulatory and policy issues within the responsibility of the ENVI Committee in

the area of Environmental policy (IP/A/ENVI/FWC/2010-003)’.

Aim

The overall objective of this study is to give an overview on the status of its practical

implementation in European Member States.

The key questions are as follows:

Are all end-of-life vehicles accounted for?

Is the concept of vehicle 'de-registration' applied consistently in the Member States?

How many ELV vehicles are exported - legally or illegally - from the Member States?

Are all ELVs properly de-polluted?

Are all ELVs recycled and what are the success rates that are achieved?

Do vehicle manufacturers meet their producer-responsibility obligations?

These questions are discussed in the individual chapters of this study.

15

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Methodology

The following sources of information were used for preparing this study:

Analysis of reports on ELV management and further information obtained by the

European Commission and European Services

7

;

Analysis of data reported by Member States on the monitoring of recycling and

recovery rates pursuant to Commission Decision 2005/293/EC

8

for the reference

years 2006, 2007 and 2008 as published by Eurostat

9

;

Questionnaire survey addressed to selected Member States

10

;

Member State representatives were contacted via email and telephone. The

questionnaire is included in the Annex to this study;

Telephone and email interviews with representatives of the waste treatment

industry and waste consultants;

Literature and internet survey.

7

Minutes of the meetings of the Working Group on Methodologies, Directive 2000/53/EC on End-of-Life Vehicles,

questionnaires completed by several Member States pursuant to Commission Decision 2001/753/EC for the period

2005 – 2008 (provided by AT, CY, EE, DE, DR, IR, NL, PL, PT, SE, UK)

8

COMMISSION DECISION laying down detailed rules on the monitoring of the reuse/recovery and reuse/recycling

targets set out in Directive 2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on end-of-life vehicles

(2005/293/EC)

9

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/waste/data/wastestreams/elvs

10

AT, BE, EE, DE, FI, SE, UK (BG, HU, ES, FR, GR, IR, IT, NL, PT without response)

16

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1. ARISING OF ELVs

Question

Are all ELVs being accounted for?

1.1. Legal background

The ELV-Directive (2000/53/EC) applies to vehicles and end-of-life vehicles, including their

components and materials.

The following definitions are laid down in Article 2 of the ELV-Directive:

‘vehicle’ means any vehicle designated as category M1 or N1 defined in Annex IIA to

Directive 70/156/EEC

11

, and three wheel motor vehicles as defined in Directive

92/61/EEC

12

, but excluding motor tricycles;

‘end-of life vehicle’ means a vehicle which is waste within the meaning of the Waste

Framework Directive (2008/98/EC)

13

.

Whereby M1 and N1 vehicles are defined according to Directive 70/156/EEC as follows

Category M1: Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers and

comprising no more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat.

Category N1: Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of goods and

having a maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tonnes.

According to the Commission Decision 2005/31/EC laying down detailed rules on the

monitoring of the reuse/recovery and reuse/recycling targets since 2006 the number of

end-of-life vehicles has to be monitored. Accompanying tables set out in the Annex of the

Decision shall be completed by the Member States on an annual basis, starting with data

for 2006 and shall be sent to the Commission within 18 months of the end of the reference

year.

1.2. Results

One crucial factor with regard to accounting of ELVs is the differentiation between ELVs and

used cars. The question when a used car ceases to be product and becomes waste

according to the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) is answered in a different way

across the EU Member States. As a consequence, there are problems in terms of

comparability of the reported data. It also has an impact on the decision whether

transboundary shipment of al vehicle is subject to the provisions of the Waste Shipment

Regulation No 1013/2006.

11

COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 1970/186/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the type-

approval of motor vehicles and their trailers

12

COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 1992/61/EEC relating to the type-approval of two or three-wheel motor vehicles

13

DIRECTIVE 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on waste and repealing certain Directives

17

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Aspects which seem to be of major importance for used cars to become an ELV are:

Does the vehicle represent ‘waste’ by the meaning that the holder discards or

intends or is required to discard the vehicle (according to the Waste Framework

Directive)?

Is there a public interest in terms of harm to the environment that the vehicle

should be considered as ELV?

Does the vehicle fulfill the technical requirements according to the national licensing

systems?

This opens a wide range of interpretations at which point a used car becomes an ELV. This

fact is also reflected in the official statistics. To allow interpretations of the official national

statistics following data seems to be of particular importance:

Car fleet

Deregistered cars

- ELV

- Used cars without waste status

Commercial and private export of deregistered cars

- Export of ELV

- Export of used cars without waste status

Data on the car fleet and de-registered cars are published on an annual basis at varying

levels of detail by national statistic agencies of the Member States, Eurostat and the

European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA)

14

. There are different approaches

concerning de-registration of vehicles across European Member States. In some countries

(e.g. in Austria, Germany, Italy) a vehicle is, as a rule, de-registered when the ownership

of the car changes. In other countries (e.g. in the UK) vehicles are not de-registered when

ownership changes. In the latter, de-registration generally takes place when the car owner

wants to dispose of the vehicle. Then, vehicles may only be re-registered and put back on

the road under exceptional circumstances and prior approval.

Data on arisings of ELVs in the Member States as well as on the export of ELVs and parts

thereof are published by Eurostat (last reference year available: 2008)

9

.

Data on the commercial export of used cars is available from the Eurostat database

COMEXT, the official European Foreign Trade Statistics

15

.

1.2.1. Automotive market

T

h

e economic crises caused a significant impact on the automotive industry in the last two

years. Despite several national scrappage programs within selected MS the overall car

production within EU 25 declined by more than 12 % in 2009 compared to 2008. Table 2

shows data

on the over

all automotive production of passenger cars in Europe.

16

14

http://www.acea.be

15

http://www.fiw.ac.at/index.php?id=367

16

http://www.vda.de

18

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Table 2: Production of passenger cars in Europe

Region 2008

2009

Change in %

Europe 18.358.696

15.111.199

-17,7

EU-25 15.999.258

13.944.501

-12,8

thereof:

Germany 5.532.030

4.964.523

-10,3

France 2.145.935

1.819.462

-15,2

Italy 659.221

661.100

0,3

Spain 2.013.861

1.832.999

-9,0

United Kingdom 1.446.619

999.460

-30,9

Source: http://www.vda.de

A big share of the overall production of new passenger car vehicles is exported from the

EU. According to ACEA the overall car fleet 2008 in the European Union is more than 223

Mio passenger cars (20 countries, except Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta,

Romania and Slovenia). Passenger cars in use are on average 8.2 years old

17

.

1.2.2. Statistics on ELVs

Th

e European Environment Agency estimated the number of end-of-life vehicles arising in

the EU-25 to be about 14 million in 2010, compared to 12.7 million in 2005

18

. This is a

number that differs significantly from the 6.2 million end-of-life vehicles in 2008 as

published by Eurostat and based on data reported by 24 Member States

19

.

17

ACEA (2008): European Motor Vehicle Parc

18

ETC/RWM 2008: Projection of end-of-life vehicles (prepared for the European Environment Agency (EEA) under

its 2007 work programme as a contribution to the EEA's work on waste outlooks)

19

Eurostat (available at : http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/waste/data/wastestreams/elvs)

19

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1.2.3. Statistics on used cars

Table 3 shows data on deregistered cars and ELV for selected

Member States to illustrate

that there is a gap of knowledge concerning the further use of a certain amount of de-

registered cars.

Table 3: Comparison of the numbers of ELVs and de-registered cars

Country data Year

Cars fleet

(passenger

cars)

17

De-registered

passenger

cars (without

re-registered

cars)

17

ELV arisings /

treated

within or

outside the

MS

20

Commercial

export of

used cars

21

De-registered passenger cars

not reported as ELVs & not

exported commercially

Column 1: Column 2:

Column 3:

Column 4:

Column 5:

number

(calculated

22

)

Column 6: %

in relation to

the overall

de-registered

passenger

cars

(calculated)

23

Austria 06 4.204.969 260.368

87.277

43.530

129.561 50 %

Austria 07 4.245.583 257.568

62.042

39.019

156.507 61 %

Austria 08 4.284.919 254.361

63.975

37.629

152.757 60 %

Belgium 06 4.929.284 458.210

131.043

224.326

102.841 22 %

Belgium 07 5.006.294 447.784

127.949

244.606

75.229 17 %

Belgium 08 5.086.756 455.478

141.521

273.036

40.921 9 %

Czech Republic 06 4.108.610 70.794

56.582

4.395

9.817 14 %

Czech Republic 07 4.280.081 91.487

72.941

27.664

-9.118 -10 %

Czech Republic 08 4.423.370 168.837

147.259

3.543

18.035 11 %

Denmark 06 2.013.899 314.899

102.202

8.990

203.707 65 %

Denmark 07 2.058.873 308.391

99.391

25.535

183.465 59 %

Denmark 08 2.105.049 301.906

101.042

16.533

184.331 61 %

Finland 06 2.489.287 105.529

14.945

866

89.718 85 %

Finland 07 2.570.356 90.239

15.792

934

73.513 81 %

Finland 08 2.682.831 37.614

103.000

428

-65.814 -175 %

Greece 06 4.446.528 63.067

29.689

2.126

31.252 50 %

Greece 07 4.805.156 64.013

47.414

327

16.272 25 %

Greece 08 5.101.410 70.308

55.201

375

14.732 21 %

Italy 06 35.297.282 1.784.147

1.379.000

124.981

280.166 16 %

Italy 07 35.680.097 2.207.336

1.692.136

101.313

413.887 19 %

Italy 08 36.105.183 1.796.898

1.203.184

70.471

523.243 29 %

Latvia 06 822.011 17.620

6.288

1.980

9.352 53 %

Latvia 07 904.869 22.167

11.882

6.537

3.748 17 %

Latvia 08 932.828 26.033

10.968

1.802

13.263 51 %

Netherlands 06 7.413.034 225.760

192.224

49.584

-16.048 -7 %

Netherlands 07 7.597.000 200.836

166.004

53.018

-18.186 -9 %

Netherlands 08 7.757.000 209.427

152.175

69.424

-12.172 -6 %

Spain 06 21.052.559 910.727

954.715

83.044

-127.032 -14 %

Spain 07 21.760.174 887.395

881.164

88.232

-82.001 -9 %

Spain 08 22.145.364 734.638

748.071

234.626

-248.059 -34 %

Sweden

24

06 4.202.463 830.123

283.450

10.836

535.837 65 %

Sweden 07 4.258.463 870.014

228.646

6.553

634.815 73 %

Sweden 08 4.278.995 950.496

150.197

6.579

793.720 84 %

Source: included in Table

20

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/waste/data/wastestreams/elvs

21

Eurostat's COMEXT Database (http://www.fiw.ac.at/index.php?id=367&L=3)

22

Column 5 = Column 2 – (Column 3 + Column 4)

23

Column 6 = Column 5 / Column 2 * 100

24

According to the Swedish EPA the numbers on de-registered cars published by ACEA are accumulated over the

years and do not represent data for the years 2006, 2007 and 2008.

20

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

In most Member States the number of ELVs represents more than 50% of the amount of

de-registered passenger cars (e.g. Belgium, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands). Thus, for

those countries the gap between the number of de-registered cars and ELVs is lower than

50%. In other Member States (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Sweden) the gap is higher,

and there is no detailed information available on the further use of more than 50% of the

de-registered cars. Following key factors are important to explain the gap concerning the

whereabouts of “De-registered passenger cars not reported as ELVs & not exported

commercially”:

Private exports of used cars

Illegal shipment of ELV and used cars

Illegal disposal

Garaging (long term)

To a smaller extent, different system boundaries of the provided statistics (data provided

by ACEA cover passenger cars only; data provided by Eurostat cover vehicle classes M1, N1

and three wheeled motor vehicles; data provided by COMEXT cover motor cars and other

motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of persons, including station wagons

and racing cars) may cause differences.

Figure 1 based on data of Table 3 shows that there are differences between the Wester

n

and the

Eastern part of the EU, strictly geographically. For the period 2007-2008 the

passenger car fleet and the number of accounted ELVs are increasing to a higher extent in

the East of Europe.

Figure 1: Development of the passenger car fleet and the ELV arisings 2007-2008

Passenger car fleet 2007-2008:

Green: Increasing 0-2 %

Brown: Increasing 2-4 %

Red: Increasing more than 4 %

Number of accounted ELVs 2007-2008:

Green: Decreasing

Brown: Increasing 0-20 %

Red: Increasing more than 20 %

Source: Umweltbundesamt based on data provided by Eurostat and ACEA

21

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1.3. Steps taken by the Commission Services to overcome

problems

Waste shipment correspondents: Draft Correspondent’s guidelines No 9 (Version 6

from 8th of June 2010) according to the Waste Shipment Regulation

(2006/1013/EC):

These Correspondents' guidelines represent the common understanding of Member

States on how Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 on shipments of waste (Waste

Shipment Regulation – WSR) should be interpreted.

The guidelines No 9 are currently (September 2010) available as draft. It gives

guidance provided for the distinction between waste vehicles and used vehicles.

Based on the definition of the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) a used

vehicle should be classified as waste if at least one of the following criteria applies:

a. The vehicle is destined for dismantling and reuse of spare parts or for

shredding/scrapping;

b. The vehicle is cut into pieces (e.g. two halves), welded up or closed by an

insulating foam (only by breaking open the waste vehicle can be made

roadworthy) and/or used as “container” for spare parts or wastes;

c. The vehicle stems from a waste collection or waste treatment system;

d. The vehicle is a write-off /is not suitable for minor repair /has badly damaged

essential parts (as a result of an accident, for example) or has no “Vehicle is

repairable” certification where a competent authority has requested it (see

paragraph 11 and Appendix 3);

e. The existence of a certificate of destruction.

The following indicators may also be relevant for classifying a used vehicle as waste:

f. The vehicle has no registration or it has been de-registered;

g. The vehicle has not had its required National technical roadworthiness test for

more than two years from the date when this was last required;

h. The vehicle has no identification number and the owner of the vehicle is

unknown;

i. The vehicle was handed over to an interim storage facility or an authorised

treatment facility;

j. The repair costs exceed the present value of the vehicle (exception: vintage cars

or vehicles) and the possibility for repair cannot be assumed (repair costs in EU-

Member State as basis for evaluation);

k. Where the vehicle poses a safety risk or a risk to the environment e.g. by:

i) Doors not being attached to the car,

ii) Discharge of fuel or fuel vapour (risk of fire and explosion),

iii) Leakage within the liquid gas system (risk of fire and explosion),

iv) Discharge of operating liquids (risk of water pollution caused by fuel, brake fuel,

anti-free liquid, battery acid, coolant liquid).

Eurosta

t

: Draft guidance document ‘How to report on end-of-life vehicles according

to Commission Decision 2005/293/EC’ (Revision by Eurostat from the 20th of April

2010)

22

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

This guidance is not legally binding but focuses on aspects of data harmonisation

and data quality, based on the experience with the reporting for the reference year

2006 and 2007 and the related data collection and evaluation conducted by the

Member States.

The guidance document states that inter alia following data should be made

available in the quality report as required by Commission Decision 2005/293/EC:

Information on the national vehicle market:

‐ Vehicles registered (Number)

‐ Average age of fleet (Years)

‐ Final de-registrations per year (Number)

‐ CoDs issued in the Member State (Number)

‐ ELVs arising in the Member State (Number)

‐ Average age of ELVs (Years)

National market information on export of used vehicles, ELVs and depolluted body

shells to other EU countries and non EU-countries:

‐ Used vehicles exported (Number)

‐ Average age of used vehicles exported (Years)

‐ ELVs exported (Number)

‐ De-polluted (and dismantled) body shell exported (Number, tonnes)

23

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1.4. Conclusions & Recommendations

The question of when a used car ceases to be product and becomes waste according to the

Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) is answered in different ways across EU Member

States. As a consequence, there are problems regarding the comparability of the reported

data and in individual cases regarding the answer to the question if a transboundary

shipment of a vehicle is subject to the provisions of the Waste Shipment Regulation No

1013/2006. To address this problem the Correspondent’s guidelines No 9 (draft status),

representing the common understanding of all Member States on how the WSR should be

interpreted, gives inter alia guidance for the distinction between ELVs and used vehicles.

Establish binding rules at European level for the distinction between ELVs and used

vehicles (addressed to the European Commission).

It is evident that data on the national vehicle markets (especially on the number of de-

registered vehicles and the imports/exports of used vehicles) is not yet consistently

available for European Member States. To address this problem the Eurostat guidance

document on “How to report on end-of-life vehicles according to Commission Decision

2005/293/EC” (Revision by Eurostat 20th April 2010) aims to enhance the quality of data

on the national vehicle market including the number de-registered vehicles and the number

of exports of used vehicles.

Request data on the national vehicle markets (addressed to the European Commission).

24

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

2. CONCEPT OF VEHICLE DE-REGISTRATION

Question

Is the concept of vehicle ‘de-registration’ applied consistently in Member States?

2.1. Legal background

According to the ELV-Directive a certificate of destruction is a condition for de-registration

of ELV (as laid down in the general provisions of the ELV-Directive):

(16) A certificate of destruction, to be used as a condition for de-registration of end-of life

vehicles, should be introduced. Member States without a de-registration system should set

up a system according to which a certificate of destruction is notified to the relevant

competent authority when the end-of life vehicle is transferred to a treatment facility.

(17) This Directive does not prevent Member States from granting, where appropriate,

temporary de-registrations of vehicles.

See also Article 5: Collection

(1) Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure:

‐ that economic operators set up systems for the collection of all end-of-life vehicles

and, as far as technically feasible, of waste used parts removed when passenger

cars are repaired,

‐ the adequate availability of collection facilities within their territory.

(2) Member States shall also take the necessary measures to ensure that all end-of

life vehicles are transferred to authorised treatment facilities.

(3) Member States shall set up a system according to which the presentation of a

certificate of destruction is a condition for deregistration of the end-of life vehicle.

This certificate shall be issued to the holder and/or owner when the end-of life

vehicle is transferred to a treatment facility. Treatment facilities, which have

obtained a permit in accordance with Article 6, shall be permitted to issue a

certificate of destruction. Member States may permit producers, dealers and

collectors on behalf of an authorised treatment facility to issue certificates of

destruction provided that they guarantee that the end-of life vehicle is transferred to

an authorised treatment facility and provided that they are registered with public

authorities.

Issuing the certificate of destruction by treatment facilities or dealers or collectors

on behalf of an authorised treatment facility does not entitle them to claim any

financial reimbursement, except in cases where this has been explicitly arranged by

Member States.

Member States which do not have a deregistration system at the date of entry into

force of this Directive shall set up a system according to which a certificate of

destruction is notified to the relevant competent authority when the end-of life

vehicle is transferred to a treatment facility and shall otherwise comply with the

terms of this paragraph.

Member States making use of this subparagraph shall inform the Commission of the

reasons thereof.

25

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

(4) Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure that the delivery of

the vehicle to an authorised treatment facility in accordance with paragraph 3 occurs

without any cost for the last holder and/or owner as a result of the vehicle's having

no or a negative market value.

Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure that producers meet all,

or a significant part of, the costs of the implementation of this measure and/or take

back end-of life vehicles under the same conditions as referred to in the first

subparagraph.

Member States may provide that the delivery of end-of life vehicles is not fully free

of charge if the end-of life vehicle does not contain the essential components of a

vehicle, in particular the engine and the coachwork, or contains waste which has

been added to the end-of life vehicle.

The Commission shall regularly monitor the implementation of the first

subparagraph to ensure that it does not result in market distortions, and if

necessary shall propose to the European Parliament and the Council an amendment

thereto.

(5) Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure that their

competent authorities mutually recognize and accept the certificates of destruction

issued in other Member States in accordance with paragraph 3.

To this end, minimum requirements for the certificate of destruction shall be

established. That measure, designed to amend non-essential elements of this

Directive by supplementing it, shall be adopted in accordance with the regulatory

procedure with scrutiny referred to in Article 11(3).

(29) The adaptation to scientific and technical progress of the requirements for treatment

facilities and for the use of hazardous substances and, as well as the adoption of minimum

standards for the certificate of destruction, the formats for the database and the

implementation measures necessary to control compliance with the quantified targets

should be effected by the Commission under a Committee procedure.

2.2. Results

In general, vehicle registration systems are differing across European countries. In order to

encourage Member States to be more flexible about the registration of cars coming from

another Member State, the European Commission has issued an interpretative

communication

25

on car registration issues. This communication sets out, in legal terms,

the minimum conditions which car registration procedures must fulfill. Within that

communication no requirements are defined to be met for de-registration of a used vehicle.

There are different approaches to the de-registration of vehicles across European Member

States. In some countries (e.g. in Austria) a vehicle is de-registered as a rule with the

change of ownership of a car. In other countries (e.g. in the UK) vehicles are not de-

registered when ownership changes. In these countries, de-registration generally takes

place when the car owner wants to dispose of the vehicle. De-registered vehicles may be

re-registered and put back on the road only under exceptional circumstances and if prior

approval has been granted.

25

COMMISSIONS INTERPRETATIVE COMMUNICATION on procedures for the registration of motor vehicles

originating in another Member State (2007/C68/04)

26

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

When a vehicle has become waste (=end-of-life vehicle) additional requirements for de-

registration have to be met. Article 5 (3) of the ELV Directive requires Member States to set

up a system according to which the presentation of a certificate of destruction (CoD) is a

condition for de-registration of the end-of life vehicle. In 2009, twenty-one Member States

reported that they had implemented the condition to present a CoD for de-registering an

ELV

1

.

In some Member States (e.g. Austria, Finland) the number of issued CoDs is not equal to

the arisings of end-of-life vehicles. This might be due to the fact that a vehicle can be de-

registered before the car owner decides that his/her car becomes waste and thus an end-

of-life vehicle. There is an information gap regarding the whereabouts of de-registered

vehicles. To close this gap, information on the further use of a vehicle should be obtained

its de-registration (e.g. in the form of a declaration that there is no intention to dispose of

the vehicle, and stating whether the car owner intends to sell or export the vehicle or keep

it in a garage).

With the Commission Decision 2002/151/EC minimum requirements for certificates of

destruction have been issued.

2.2.1. Implementation of Article 5 (3) according to MS reporting

According to the Commission’s report on the imp

l

ementation of the ELV-Directive for the

period 2005-2008

74

all responding Member States (22) except Belgium reported having set

up a system according to which the presentation of a CoD is a condition for deregistration

of a vehicle. The Belgian case is followed by the Commission. Nine Member States used an

option to allow producers, dealers or collectors to issue a CoD on behalf of an authorised

treatment facility provided there is a guarantee that the ELVs are transferred to authorised

treatment facilities:

Belgium

74

:

The Commission closed the infringement procedure started in 2003 because Belgium had

adopted and communicated its transposition measures. In 2005 a new enforcement action

was set up as a result of a conformity inquiry by the Commission. The Commission sent a

letter to Belgium on 16 March 2005 with questions which needed to be clarified by the

authorities. The Flemish Region responded to these questions in July 2005 and promised to

make and actually made some changes to its legislation. The information sources consulted

indicated no further steps by the European Commission.

In order to increase the traceability of vehicles and improve the collection rate, the federal

agency responsible for registration of vehicles (DIV or Dienst Inschrijving Voertuigen)

started recently a study on the feasibility and opportunity to introduce a new registration

system in Belgium. The federal government aims to introduce in 2009 a procedure by

which seller and buyer of a vehicle need to identify themselves via their electronic identity

card and need to confirm the transaction via an electronic signature. Thereby the chassis

number will be registered too. At this moment only the number plates are linked with

identity details of individuals. In order to encourage people to deregister their end-of life

vehicle and to get a certificate of destruction, the policy makers are considering options to

financially reward people for doing this. A possible way of doing this is to exempt these

persons from paying their car tax. The regional waste authorities and FEBELAUTO have

been zealous advocates of this new registration system.

27

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

According to the survey done within the project there is the information that this new

registration system has not been introduced yet.

UK

74

:

The number of CoDs gathered has been much lower than expected. The UK Liberal

Democrats environment spokesman in the European Parliament, Chris Davies, explained

this by arguing that Britain's 1,200 authorised treatment facilities would issue about

500,000 CoDs in 2006, while the remaining 1.5 million ELVs would be dismantled without

the facility producing the only document that guarantees the sound treatment of the ELV.

This is apparently due to a lack of implementation by the Driver and Vehicle Licensing

Agency (DVLA) that apparently allows last owners to tick a box on their vehicle

deregistration form to state that they have scrapped their car themselves, but without

requiring the certificate. There is however evidence that the responsible Agencies are now

working to prevent operation by all non licensed facilities and DVLA is considering whether

the alternative means of notification should be withdrawn.

According to the questionnaire done within the project there is indication given that the

existence of the registration document notification route has reduced the significance of the

CoD in the UK. This problem is now being addressed via in the national registration

document "scrappage tick-box" is being progressively removed over the course of the next

year so that private scrappage will be disabled.

2.2.2. Additional information on the implementati

on of Arti

cle 5(3)

Additional information on the implementation of Article 5(3) was gathered by a

questionnaire survey within the project and by evaluation of completed questionnaires

reported by MS pursuant to Commission Decision 2001/753/EC for the period 2005-2008.

Austria:

According to Paragraph 5(3) of the Austrian Ordinance on ELV

26

a certificate of

destruction

27

has to be issued to the holder and/or owner when the end-of life vehicle is

transferred to an authorised take-back point or treatment facility and this is a condition for

de-registration of a ELVs. The provision is introduced in Paragraph 43(1a) of the Austrian

Motor Vehicles Act.

Germany:

According to Paragraph 4(2) of the German Ordinance on ELV

28

a certificate of destruction

has to be issued to the holder and/or owner when the end-of life vehicle is transferred to

an authorised dismantling facility (or take-back points on the behalf of the dismantling

facilities).

29

The provision is introduced in Paragraph 15 of the German Vehicle Registration

Ordinance.

26

http://www.umweltnet.at/article/articleview/26635/1/7999/ (German language)

27

http://wko.at/up/Alt-Pkw-Verwertungsnachweis.pdf (German language)

28

http://bundesrecht.juris.de/bundesrecht/altautov/gesamt.pdf (German language)

29

According to the implementation report on the ELV Directive (EC 2009) ARGE Altauto states that there are

occasional enforcement problems of the ELV-Ordinance by the local authorities. For example the submission of a

certificate of deconstruction in line with the ELV ordinance as a precondition of car deregistration is not always

respected.

28

End of life vehicles: Legal aspects, national practices and recommendations for future successful approach

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Cyprus

33

:

Article 9(5) of L.157(I)/2003 provide for the obligation of the authorised treatment facilities

to issue a ‘Certificate of Destruction’ for each ELV they receive, and deliver or post it to the

competent authority and to the last person who was in possession of the vehicle. This

certificate is used for de-registration of the vehicle, in accordance to the ‘Motor Vehicles

and Road Traffic Laws’. The latter was amended by Law numbered L.146 (I)/2003 to make

the ‘Certificate of Destruction’ a necessary and sufficient document for de-registration of a

waste vehicle.

Finland:

According to Section 7 of the Government Decree on End-of-Life Vehicles (581/2004)

30

a

certificate of destruction can only be issued by a collector as referred to in section 18(1) of

the Waste Act or by a treatment operator. The collector or treatment operator of an end-of-

life vehicle shall give the holder of the end-of-life vehicle a certificate of destruction free of

charge and shall also immediately enter or deliver notification of receipt of the vehicle to

the vehicle register maintained by the Finnish Vehicle Administration for de-registration of

the vehicle as laid down in the Decree on the Vehicle Registration (1598/1995).

Hungary

33

:

Only authorised dismantlers may issue certificates of destruction (Article 7(3) of the

Government Decree and Ministry of Economy and Transport Decree 29/2004 (III.12)).

Producers or recipients may issue certificates of destruction on behalf of a dismantler.

Vehicles may be definitively withdrawn from service only upon presentation of the

certificate (Ministry of the Interior Decree 41/2005 (X. 7)).

Ireland:

According to point 19 to 26 of the Waste Management (End-of-Life Vehicles) Regulations

2006

31

a certificate of destruction in a form specified by the Minister has to be issued to the

registered owner of an end-of life vehicle when an ELV is transferred to an authorised

treatment facility.

32

A Transfer Order amended the relevant provisions of the regulations to

require authorised treatment facilities to notify the Minister for Transport of the issue of

certificates of destruction.

Italy

33

:

Article 5, paragraph 6 of Legislative Decree 209/2003 stipulates that at the time of a

handover to the collection centre of a vehicle intended for dismantling, the proprietor of the

centre must issue to the keeper of the vehicle, the dealer, or the management of the

branch of the vehicle's manufacturer or of the car dealer a suitable certificate of destruction

accompanied by a description of the state of the vehicle delivered. Furthermore a

commitment has to be provided to immediately proceed with de-registration with the PRA

(Vehicle Registration Office) if this has not already been done and to treat the vehicle.

30

http://www.autopurkamoliitto.fi/romuajoneuvoasetus.pdf

31

http://www.environ.ie/en/Environment/Waste/ProducerResponsibilityObligations/EndOfLifeVehicles/

32

According to the implementation report on the ELV-Directive (EC 2009) it is stated that stated that it has been

equally difficult to identify the actual numbers of end-of life vehicles arising in Ireland. Up until the implementation

of the ELV Directive there was no system for deregistration in Ireland. Therefore, the levels of ELV production

have been estimated in a range of ways.

29

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy

____________________________________________________________________________________________

To this end, within three days of the handover of the vehicle, this dealer or management or

proprietor needs to return the certificate of ownership, registration document and the

registration plates of the end-of-life vehicle in line with the procedure laid down by

Presidential Decree No. 358 of 19 September 2000. The issue of the declaration of taking

charge of the vehicle or the certificate of destruction releases the keeper of the end-of-life

vehicle from civil, criminal and administrative responsibilities associated with ownership and

correct management of the vehicle.

Latvia

33

:

In the Law on End-of-life vehicles and in the Cabinet of the Ministers regulations Nr. 241 on

the ‘Arrangement of filling and delivery of certificates of destruction of end-of life vehicles’

there are rules governing the completion and issuing of certificates of destruction. The rules

describe the implementation of the system of ELV de-registration based on the certificates

of destruction, the requirements regarding the issuing of a certificate of destruction to the

last owner of an ELV, and the cases where treatment facilities have the right to financial

reimbursement. Once the treatment facility has received an end-of-life vehicle, it issues a

certificate of destruction.

Lithuania

33

:

Paragraph 12 and 13 of the Rules for the Management of End-of-life Vehicles (adopted by

Order No 710 of the Minister of Environment of the Republic of Lithuania of 24 December

2003) defines rules concerning the issuing of certificates of destruction. In the case of de-

registration of a class M1 or N1 vehicle, a certificate of destruction needs to be issued by

the authorised treatment or collection undertaking; three copies: first copy to be given to

the owner of the end-of-life vehicle, second copy to be retained by the issuing undertaking,

and third copy to be presented to the Regional Environmental Department that has issued a

permit.

Poland

33

:

The de-registration system was laid down in Article 79(1) of the Act of 20 June 1997 - Road

Traffic Law (Journal of Laws 2005, No 108, item 908, as amended) and in the Regulation of

the Minister for Infrastructure of 25 March 2005 laying down the method of cancelling