Andrews University Andrews University

Digital Commons @ Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University

Dissertations Graduate Research

2012

An Ex Post Facto Study on the Relationship Between Self-An Ex Post Facto Study on the Relationship Between Self-

Reported Peer-to-Peer Mentoring Experiences and Instructor Reported Peer-to-Peer Mentoring Experiences and Instructor

Con;dence, Institutional Loyalty, and Student Satisfaction among Con;dence, Institutional Loyalty, and Student Satisfaction among

Part-Time Instructors Part-Time Instructors

Carolyn A. Watson

Andrews University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations

Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Higher Education

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Watson, Carolyn A., "An Ex Post Facto Study on the Relationship Between Self-Reported Peer-to-Peer

Mentoring Experiences and Instructor Con;dence, Institutional Loyalty, and Student Satisfaction among

Part-Time Instructors" (2012).

Dissertations

. 1529.

https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1529

https://dx.doi.org/10.32597/dissertations/1529/

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @

Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital

Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Thank you for your interest in the

Andrews University Digital Library

of Dissertations and Theses.

Please honor the copyright of this document by

not duplicating or distributing additional copies

in any form without the author’s express written

permission. Thanks for your cooperation.

ABSTRACT

AN EX POST FACTO STUDY ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

SELF-REPORTED PEER-TO-PEER MENTORING EXPERIENCES

AND INSTRUCTOR CONFIDENCE, INSTITUTIONAL

LOYALTY, AND STUDENT SATISFACTION

AMONG PART-TIME INSTRUCTORS

by

Carolyn A. Watson

Chair: Erich Baumgartner

ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH

Dissertation

Andrews University

School of Education

Title: AN EX POST FACTO STUDY ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF-

REPORTED PEER-TO-PEER MENTORING EXPERIENCES AND

INSTRUCTOR CONFIDENCE, INSTITUTIONAL LOYALTY, AND

STUDENT SATISFACTION AMONG PART-TIME INSTRUCTORS

Name of researcher: Carolyn A. Watson

Name and degree of faculty chair: Erich Baumgartner, Ph.D.

Date completed: August 2012

Problem

The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Educational Statistics estimate

that part-time faculty now comprises almost half of the faculty labor force; many believe

this statistic has been gravely underestimated. Powerful unions like the American

Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the American Association of Colleges

and Universities (AACU) believe that universities are relying too heavily on part-time

faculty members and that this over-reliance threatens the quality of higher education

today. The debate surrounding the use of part-time faculty seems to focus on issues of

instructor confidence, loyalty, and student satisfaction. Many question whether a part-

time faculty member can deliver quality instruction and contribute to the community of

learners as well as their full-time tenured counterparts. This dissertation explores whether

peer mentoring is an effective means to increase confidence, loyalty to the organization,

and student satisfaction scores among part-time faculty members.

Method

An ex post facto research design was used to explore the quality of a previous

peer-mentoring experience and its relationship to several dependent variables. The

sample was comprised of the eligible 600 part-time faculty who taught in the School of

Business at a large, private, Christian, mid-western university. Data were collected using

an online survey instrument, comprised of four subscales. After the data were collected,

descriptive statistics were generated and a Pearson r was calculated and correlational

matrixes generated to initially determine what, if any, significant relationships existed

between the independent and dependent variables. Linear regression models were

generated to answer the research hypotheses.

Results

One of the study’s major findings was the significant relationship that exists

between mentoring and instructor confidence. Independent variables, such as age and

gender, did not significantly affect these results. However, part-time faculty who taught

for other universities tended to score higher in the measure of instructor confidence than

those with experience teaching only for the University.

While the fidelity or the quality of the mentoring program was not significantly

related to instructor confidence, it was significantly related to institutional loyalty. This

finding was independent of the type of mentor and the other demographic variables,

including teaching at other universities. This was a surprising find, particularly in light of

the way teaching at multiple institutions is portrayed negatively in the literature.

Finally, the research asked whether part-time faculty members who received

mentoring have students with higher means on end-of-course survey forms, which are

used to measure student satisfaction. The data analysis revealed that no significant

relationship exists between mentoring and student satisfaction scores. The research

design and response rate (25%) limit the ability to generalize from these findings.

Conclusions

The research re-affirmed that mentoring is an effective management strategy.

Part-time faculty members who receive mentoring tended to score significantly higher on

measures of instructor confidence. The quality of the peer-mentoring experience did not

appear to be as important as the fact that mentoring, in some form or another, occurred.

In addition, teaching at other universities did not negatively influence the significant

relationship between mentoring, instructor confidence, and institutional loyalty.

Secondly, the quality or fidelity of the mentoring program seems to be important

as it relates to institutional loyalty. While any type of mentoring could result in increased

confidence, if the goal of the University is to develop a sense of institutional loyalty, then

developing a quality mentoring program and fostering quality mentoring relationships

would seem to be important.

This study found no significant relationship between a faculty member’s self-

reported perception of a peer-mentoring experience and the level of student satisfaction.

That no relationship was found in the course of this study does not mean that a

relationship does not exist. It could be that the instrument used to measure student

satisfaction was not valid or that the “halo effect” influenced the student ratings.

Finally, I developed subscales created to measure instructor confidence and the

fidelity of the mentoring program, which have the potential to aid further research and

administrators in the development of both professional development activities and

organizational mentoring programs. Further research can use alternative strategies for

improving the estimates of reliability and validity of these two instruments.

Andrews University

School of Education

AN EX POST FACTO STUDY ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

SELF-REPORTED PEER-TO-PEER MENTORING EXPERIENCES

AND INSTRUCTOR CONFIDENCE, INSTITUTIONAL

LOYALTY, AND STUDENT SATISFACTION

AMONG PART-TIME INSTRUCTORS

A Dissertation

Presented in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy

by

Carolyn A. Watson

August 2012

© Copyright by Carolyn A. Watson 2012

All Rights Reserved

AN EX POST FACTO STUDY ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

SELF-REPORTED PEER-TO-PEER MENTORING EXPERIENCES

AND INSTRUCTOR CONFIDENCE, INSTITUTIONAL

LOYALTY, AND STUDENT SATISFACTION

AMONG PART-TIME INSTRUCTORS

A dissertation

presented in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree

Doctor of Philosophy

by

Carolyn A. Watson

APPROVAL BY THE COMMITTEE:

________________________________ _____________________________

Chair: Erich Baumgartner Dean, School of Education

James R. Jeffery

________________________________

Member: Isadore Newman

________________________________

Member: Sylvia Gonzalez

________________________________ _____________________________

External: David Penno Date approved

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ..................................................... viii

LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................... xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... xii

Chapter

I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................1

Background of the Problem .......................................4

Statement of the Problem .........................................8

Purpose of the Study ............................................9

Assumptions ..................................................9

Research Questions ............................................10

Research Question 1 .......................................10

Research Question 2 .......................................10

Research Question 3 .......................................11

Theoretical Framework .........................................11

Significance of the Study ........................................15

General Research Methodology ..................................17

Limitations ...................................................17

Delimitations .................................................19

Definition of Terms ............................................19

Organization of the Study .......................................22

II. LITERATURE REVIEW ..........................................24

Part-time Faculty ..............................................25

The Rise in Use of Part-time Faculty ..........................25

The G.I. Bill ........................................27

The Money Factor ...................................28

Flexibility in Scheduling ..............................29

Supply and Demand ..................................30

The Debate Related to the Use of Part-time Faculty ...................31

Quality of Instruction ......................................31

The Role of Academic Freedom .............................33

Job Security and Other Financial Considerations ................34

Contributions of Part-time Faculty............................35

iv

Issues Related to Part-time Faculty ................................36

Instructor Confidence ......................................36

Instructor Confidence Defined ..........................38

Role of Inclusion in Instructor Confidence ................39

Institutional Loyalty .......................................41

Transitory Nature of Part-time Appointments ..............41

Institutional Loyalty Defined ...........................42

Types of Institutional Loyalty ..........................44

Student Satisfaction .......................................47

Student Satisfaction Defined ...........................48

Validity of Using Student Satisfaction Surveys .............49

Students and SETs ...................................51

Instructors and SETs ..................................51

SETs as Measure of Instructor Effectiveness ...............52

Summary of Issues Related to Part-time Faculty .................53

Mentoring ...................................................54

Mentoring: A Definition ...................................55

Types of Mentoring Programs ...............................57

Spontaneous Mentoring .........................................57

Systematic Mentoring ................................. 59

Peer Mentoring ......................................62

Developing Systematic Mentoring Programs ...................65

Benefits of Mentoring .....................................69

Conclusion ...................................................71

III. METHODOLOGY ...............................................74

Description of Participants ......................................74

Data Collection Procedures ......................................76

Design of the Study ............................................76

Internal Validity ..........................................77

External Validity .........................................80

Statement of Hypotheses ........................................80

Hypothesis Statements Related to Instructor Confidence ..........81

Hypothesis Statements Related to Mentoring and

Instructor Confidence ..............................81

Hypothesis Statements Related to Mentoring, Fidelity,

and Instructor Confidence ...........................82

Hypothesis Statements Related to Mentoring, Type of

Mentor, and Instructor Confidence ....................83

Hypothesis Statements Related to Institutional Loyalty ...........85

Hypotheses Related to Mentoring and Institutional

Loyalty ..........................................85

Hypotheses Related to Fidelity and Institutional Loyalty .....86

Hypothesis Statements Related to Type of Mentor and

Institutional Loyalty ................................87

v

Hypothesis Statements Related to Student Satisfaction ............89

Hypotheses Related to Mentoring and Student

Satisfaction ......................................89

Hypotheses Related to Fidelity and Student Satisfaction ......90

Hypothesis Statements Related to Type of Mentor and

Student Satisfaction ................................91

The Variable List ..............................................92

The Instrumentation ............................................95

Online Survey Instrument ..................................96

Part I—Informed Consent .............................96

Part II—Tell Us about You ............................96

Part III—Tell Us How You Feel About the University .......96

Part IV—Tell Us What You Know ......................98

Part V—Tell Us About Your Mentoring Experience ........103

Part VI—Conclusion ................................105

End-of-Course Surveys ...................................106

Estimates of Validity and Reliability ..............................107

Estimates of Validity .....................................107

Field Testing ...........................................108

Estimates of Reliability ...................................110

Fidelity Measures .............................................111

Data Analysis Plan ............................................113

Summary of Methodology ......................................116

IV. SETTING OF THE RESEARCH ...................................118

The University ...............................................118

The University Mentoring Program ...............................120

The Philosophy of the Mentoring Program ....................120

The Mentoring Program Outcomes ..........................121

Qualifications of the Mentor ...............................122

The Mentoring Program Model .............................124

Conclusion ..................................................127

V. RESULTS .....................................................128

Response Rate ...............................................128

Descriptive Statistics ..........................................129

Fidelity Measure .............................................138

Correlation Matrix ............................................141

Multiple Regression Analysis ...................................143

Instructor Confidence Variables ............................143

Hypotheses Related to Mentoring and Instructor

Confidence ......................................145

Results Related to Mentoring and Instructor Confidence ....146

Hypotheses Related to Fidelity and Instructor Confidence ...150

vi

Results Related to Fidelity and Instructor Confidence .......151

Hypothesis Statements Related to Type of Mentor and

Instructor Confidence .............................152

Results Related to Type of Mentor and Instructor

Confidence ......................................153

Institutional Loyalty Variables ..............................158

Hypotheses Related to Mentoring and Institutional

Loyalty .........................................159

Results Related to Mentoring and Institutional Loyalty ......160

Hypotheses Related to Fidelity and Institutional Loyalty ....160

Results Related to Fidelity and Institutional Loyalty ........162

Hypothesis Statements Related to Type of Mentor and

Institutional Loyalty ...............................165

Results Related to Type of Mentor and Institutional

Loyalty .........................................167

Student Satisfaction Variables ..............................167

Hypotheses Related to Mentoring and Student

Satisfaction .....................................168

Results Related to Mentoring and Student Satisfaction ......169

Hypotheses Related to Fidelity and Student Satisfaction .....170

Results Related to Fidelity and Student Satisfaction ........171

Hypothesis Statements Related to Type of Mentor and

Student Satisfaction ...............................172

Results Related to Type of Mentor and Student

Satisfaction .....................................173

Conclusion ..................................................174

VI. SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..........175

Summary ...................................................175

Purpose ................................................176

Research Methodology....................................177

Limitations .............................................178

Conclusions .................................................179

Conclusions for Research Question 3 ........................182

Discussion ..................................................183

Instructor Confidence .....................................184

Institutional Loyalty ......................................186

Student Satisfaction ......................................188

Theoretical Framework ...................................190

Recommendations for Practice ..................................192

Recommendations for Further Research ...........................200

Summary of the Study .........................................203

vii

Appendix

A. DEFINITION OF VARIABLES ....................................205

B. UNIVERSITY MENTORING MODEL ..............................212

C. LIST OF EXPERT JUDGES .......................................226

D. INSTRUMENTATION ...........................................228

E. INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD DOCUMENTS ...................240

REFERENCE LIST ....................................................245

VITA ................................................................260

viii

LIST OF TABLES

1. Likert’s System 4 Management Theory ....................................14

2. Descriptive Statistics for Response Rate ..................................129

3. Descriptive Statistics for Mentoring Status ................................130

4. Descriptive Statistics for Type of Mentoring Experiences .....................130

5. Descriptive Statistics for Gender ........................................132

6. Descriptive Statistics for Ethnicity .......................................133

7. Descriptive Statistics for Educational Level ................................135

8. Descriptive Statistics for Age ...........................................136

9. Descriptive Statistics for Years of Service ................................. 136

10. Descriptive Statistics for Number of Modules Taught .......................137

11. Descriptive Statistics for Taught at Other Universities ......................138

12. Descriptive Statistics for How Many Other Universities .....................139

13. Descriptive Statistics for Teaching Level ................................. 140

14. Fidelity Score Frequencies ............................................141

15. Correlation Matrix for Confidence, Loyalty, Student Satisfaction, and

Received Mentoring ...............................................142

16. Correlation Matrix for Confidence, Loyalty, Student Satisfaction, and

Fidelity .........................................................142

17. Correlation Matrix for Confidence, Loyalty, Student Satisfaction, and Type

of Mentor ........................................................144

18. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Age ...............................................147

ix

19. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Gender ............................................147

20. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Ethnicity ...........................................148

21. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Length of Service ....................................148

22. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Number of Courses Taught ............................148

23. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Educational Level ...................................149

24. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Teaching Level ......................................149

25. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Mentoring, Instructor

Confidence, and Teaches at Other Universities ..........................149

26. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Age ...............................................154

27. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Gender ............................................155

28. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Ethnicity ...........................................155

29. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Length of Service ....................................156

30. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Number of Courses Taught ............................156

31. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Educational Level ...................................157

32. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Teaching Level ......................................157

33. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Type of Mentor, Instructor

Confidence, and Teaches at Other Universities ..........................158

x

34. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Age ..................................................163

35. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Gender ...............................................163

36. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Ethnicity ..............................................163

37. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Length of Service .......................................164

38. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Number of Courses Taught ...............................164

39. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Educational Level ......................................164

40. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Teaching Level .........................................165

41. Regression Models for Hypothesis Statements: Fidelity, Institutional

Loyalty, and Teaches at Other Universities .............................165

42. Definition of Variables ...............................................206

xii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It has been said that behind every successful man is a successful woman. A

greater truth might be that behind each success is a myriad of individuals whose

mentoring, assistance, guidance, and encouragement were essential. I would like to take

the opportunity to acknowledge the infinite patience and wisdom of my committee

members, Dr. Erich Baumgartner (chair) and Dr. Sylvia Gonzalez (content specialist).

Their commitment to excellence inspired me to achieve beyond what I could by myself. I

would like to extend a special thank-you to my methodologist, Dr. Isadore Newman. His

ability to communicate complex statistical concepts into terms a fledging Ph.D. student

can understand and enjoy is unparalleled.

I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Spring Arbor University and

the University in which this research took place. The visionary leadership of both schools

recognized early on the value and contribution of this study and worked diligently to

support this research and remove all obstacles. I would also like to thank the part-time

faculty members in the School of Graduate and Professional Studies at Spring Arbor

University. Working with them for over a decade, I have experienced firsthand their

commitment to excel and their passion for their students. They were the inspiration for

this research.

1

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Harvard College, founded in 1636, is the oldest institution of higher learning in

America (Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College, 2007). Sixteen years after the

Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, young Harvard tutors, not faculty, stood before

individuals and small groups of students. These young men taught and instructed the next

generation of clergy in order “to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity;

dreading to leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches” (Presidents and Fellows of

Harvard College, 2007, para. 4). For centuries, the Harvard model of education stood

resolute, and faculty members in colleges and universities continued to be merely tutors,

young men who had recently completed baccalaureate studies.

However, in the 19

th

century it became increasingly common to hire faculty to

teach in one particular area of expertise or specialization (Carrell, as cited in Schuster &

Finkelstein, 2006). This specialization meant more “formal preparation” and a “graduate

education” (Schuster & Finkelstein, 2006, p. 23). This advanced preparation marked a

shift in the transitory or temporary nature of the college tutor to a lifelong career

commitment to teaching (McCaughey, 1974).

Students also became empowered; educators like Charles Elliot, President of

Harvard College, advocated for an elective system of higher education. He proposed that

each student be allowed to select the course of study he or she would pursue (Schuster &

2

Finkelstein, 2006). For a hundred years, full-time, professional faculty, who were more

specialized, taught students who were more empowered, until the economic,

demographic, and technological shifts of a post-World War II era interrupted this

seamless fabric of academic life (Schuster & Finkelstein, 2006).

In 1944, Congress enacted the G.I. Bill. This legislation resulted in the infusion of

large numbers of returning veterans into an unprepared university system (Schuster &

Finkelstein, 2006). This influx of students, coupled with a decrease in the availability of

full-time, qualified faculty, resulted in universities and colleges turning to the use of part-

time faculty members in the 1960s (Bowen & Schuster, 1986). According to Bowen and

Schuster (1986), in 1960, 35% of all faculty appointments were for part-time faculty

members. By 2006, this 35% had grown to 46%; if you include other forms of contingent

faculty (graduate student instructors, post-doctoral fellows, and full-time non-tenure-track

faculty) the percentage of contingent faculty rose to 65% (AAUP, 2006). The means that

fully “two-thirds of all faculty employed in 2003” (AAUP, 2006, p. 6) were part-time and

contingent faculty. Schuster and Finkelstein (2006) call this a “seismic shift” (p. 222).

The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Educational Statistics confirm

this and estimate that part-time faculty alone now comprises almost half of the faculty

labor force (Snyder & Dillow, 2012). In fact, many believe that this fact has been

“gravely underestimated” (R. Wilson, 1999, p. A15). Because of the variance in how

researchers define part-time faculty, some believe they are underreported (Lerber, 2006).

Graduate assistants, guest lecturers, visiting professors, and fellowships are just some of

the labels used (Ivey, Weng, & Vahadji, 2005; Reichard, 1998). Researchers seem to

3

agree that the use of part-time faculty is grossly underestimated, which raises the

question, “Are universities and colleges relying too heavily on part-time faculty?”

The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) believes so.

“Over-reliance on part-time and other ‘contingent’ instructional staff diminishes faculty

involvement in student learning” (Benjamin, 2002, p. 4). In addition, the American

Association of University Professors (AAUP) concurs. In 2006, the AAUP issued the

following statement: “As the faculty collectively grows more contingent, the quality of

higher education itself is threatened” (AAUP, 2006, p. 12).

More and more voices seem to be suggesting that the use of part-time faculty

members jeopardizes the academic integrity of the instructional process (Benjamin, 2002;

Elman, 2002). One author went so far as to say that the use of part-time faculty is the

“major scandal of higher education today” (Arden, 1989, p. A48). Most of those who

deplore the use of part-time faculty cite concerns over the part-time faculty members’

isolation from the larger, educational community (Beem, 2002; Benjamin, 2002; Bradley,

2004). Balch (1999) expands on these concerns and lists several other factors such as

teaching quality, commitment to the college or university, and the time available for part-

time faculty members to spend with students outside of class. Do these “invisible people

of higher education,” as Arden (1989, p. A48) calls them, contribute to the culture of

excellence that American universities and colleges strive for?

The AAUP believes they do not. And the union believes this continued growth

trend is a “problem” (AAUP, 2006, p. 6). This powerful union is careful to note that the

problems are not related to the individuals who are, for the most part, “able teachers and

scholars” (AAUP, 2006, p. 6). Rather the problem lies in the nature of the part-time

4

faculty member’s employment conditions, the lack of support provided to part-time

faculty, and the lack of academic freedom (AAUP, 2006).

Others have questioned whether this choir of voices has not missed an important

side of the debate. While citing some concerns regarding the uses of part-timers, Balch

(1999) also concluded that part-time faculty members are qualified, highly committed,

and fulfill their duties and responsibilities conscientiously. For others, the use of adjuncts

represents an essential link between the theoretical strongholds of ivory tower

universities and the front lines of the pragmatic professional. The President of Indiana

University concluded that “part-time instructors are necessary to teach specific courses or

to bring specific professional experience to the classroom” (Brand, 2002, p. 21). Arden

(1989) agrees, “Adjuncts are a source of expertise that greatly enriches the educational

experience of students” (p. 17).

It is difficult to know who to believe as the controversy swirls. If the use of part-

time faculty poses such a danger and a threat to the academic integrity of colleges and

universities, why does the trend continue? One needs a clearer understanding of the

issues related to the use of part-time faculty to more fully comprehend the problem and

how best to address it.

Background of the Problem

The numbers do not lie. By conservative estimates, university and college

administrators are giving almost half of post-secondary faculty teaching assignments to

part-time faculty. For better or worse, part-time faculty members are here to stay

(Benjamin, 2002; Snyder & Dillow, 2012). The U.S. Department of Labor predicts that

post-secondary teaching positions will grow faster than the national average and that a

5

significant number of these positions will be for part-time professors (Bureau of Labor

Statistics, 2004).

Today, the U.S. Department of Education confirms this continuing trend (Snyder

& Dillow, 2012). But tenured faculty, administrators, and accrediting bodies are

wrestling with questions and concerns related to the use of part-time faculty (AAUP,

2006, 2009; Schuster & Finkenstein, 2006). Can a part-time faculty member deliver

quality instruction and contribute to the community of learners as well as their full-time,

tenured counterparts? The debate surrounding the use of full-time versus part-time

faculty members seems to focus on the following three concerns: quality of instruction,

isolation and loyalty, and student interaction.

Some maintain that adjunct faculty members are at a disadvantage. They are

afforded few opportunities for professional growth, and the opportunities that are offered

to them seem to be scheduled during times when work commitments keep adjuncts from

attending (Phillips, 2002). Benjamin (2002) notes that part-time faculty members lack

“professional evaluation . . . supports and, often-collegial involvement enjoyed by the

full-time, tenure-track faculty” (p. 7). When university administrators do not give part-

time faculty the same level of support as full-time, tenured track faculty, it is no wonder

that questions of confidence and quality emerge. According the AAUP (2006), this

“clearly represents a substantial limitation on their functioning as faculty” (p. 9).

This lack of support is evident when, after an adjunct faculty member is assigned

his or her first teaching assignment, the part-timer is set adrift to either sink or swim.

These “add-on” faculty members seldom interact with the full-time faculty and rarely

receive “constructive feedback on the effectiveness of their teaching” (Beem, 2002, p. 2).

6

In addition to the question of quality instruction, some note that part-timers tend

to be isolated from the larger educational community (AAUP, 2006; Balch, 1999; Beem,

2002; Benjamin, 2002; Bradley, 2004). Balch (1999) notes that a part-time member’s

“commitment to the college or university” is a concern (p. 33). Some adjuncts themselves

note there is a “strong sense of second class citizenship” (Foster & Foster, 1998, p. 11).

Whereas full-time, tenured track faculty members have a “stake in the institution,”

“temporarily employed faculty . . . feel less connected to the institution and less

empowered” (Bradley, 2004, p. 30). Cohen (1999) describes the issue like this:

Part-timers are . . . symbolic of a new class of migrant workers. While they are not

picking grapes, these laborers are wandering around the fields of academia, scraping

together teaching assignments from different institutions while the fruits of full-time

professorship—security, remuneration, stature, and academic freedom—remain out of

reach. (para. 3)

These twin concerns of the quality of instruction provided by part-time faculty

members and the feelings of isolation they experience are major issues that raise the

question, “What impact might this have on a student’s perception and satisfaction with

his or her educational experiences?” Do full-time faculty members truly provide a better

educational experience than part-time instructors do? Elman (2002) believes they do and

notes that the use of part-time faculty seriously hinders the quality of the student’s

educational experience.

Benjamin (2002) also believes that the use of part-time faculty has a negative

impact on student learning. The transitory nature of part-time faculty appointments and

the fact that they rarely have a campus office could lead one to conclude that full-time

faculty members devote more time and energy to their students than part-time faculty

(Benjamin, 2002; Bowen & Schuster, 1986). If this is true, it seems logical to conclude

7

that students would be more satisfied with the instruction they receive from full-time

faculty. AAUP (2006) notes that part-time faculty are not in a position to develop

relationships with their students, they lack the support to provide students with a quality

education experience, and, without the protection that academic freedom provides, part-

time faculty are less likely to challenge students and hold them to high academic

standards. But evidence that these negative results actually exist is virtually non-existent.

The reality is that research concerning the effectiveness of adjuncts is “scant” (Klein,

Weisman, & Smith, 1996, para. 12).

There is a plethora of literature that records recommendations on how to govern

the use of adjunct faculty. The specific recommendations vary, but common themes are

to provide support, training, and professional development opportunities and to include

adjunct faculty in the greater, scholarly community (AAUP, 2006; Arden, 1989; Balch,

1999; Beem, 2002; Rice, 2004). Many of the concerns and recommendations fall into the

categories of increasing instructor confidence (AAUP, 2003; Meacham, 2002), loyalty to

the organization (AAUP, 2006; Beem, 2002; Bradley, 2004; Cohen, 1999), and student

satisfaction (AAUP, 2006; Balch, 1999; Benjamin, 2002; Elman, 2002).

Part-time faculty members themselves have identified a key strategy to deal with

these issues: mentoring by more experienced faculty. Feldman and Turnley (2001)

concluded that part-time faculty members believe that with “more mentoring from senior

colleagues and greater integration into their larger work groups” instructional quality

could be improved (p. 14). Since a mentor is a guide, someone who has gone before and

can now show the way (Clutterbuck & Megginson, 1999; Cunningham, 1999; Tobin,

1998), it seems logical to assume that an experienced, part-time faculty member may be

8

uniquely qualified to mentor other part-time faculty members. In an effort to provide

insight in to issue, this dissertation explores the relationship between instructors’ peer-to-

peer mentoring experiences and their confidence as instructors, their loyalty to the

institution, and the satisfaction of students with their teaching.

Statement of the Problem

Since adjuncts themselves have identified mentoring as a means to improve

instruction and minimize the feelings of isolation often associated with a part-time faculty

appointment, this study picks up this line of thought. I found no studies that specifically

explored the ability of peer mentoring to assist in increasing the competence and

confidence of part-time faculty or to decrease the sense of isolation that surrounds them.

As noted earlier, these dual issues of instructor confidence and instructor isolation from

the rest of the faculty give rise to questions about how students perceive the quality of the

instruction they receive. Since universities routinely measure student satisfaction through

end-of-course evaluations this is a factor that can easily be explored.

With almost 50% of all undergraduate courses in the United States being taught

by adjunct faculty (Snyder & Dillow, 2012), it is essential that university leaders address

how best to provide support and inclusion for these isolated members if universities and

colleges are to continue to provide quality education. The focus of this study is the

relationship between part-time faculty members’ peer-mentoring experiences and their

confidence as instructors, their loyalty to the hiring institution, and their students’

satisfaction with their teaching.

9

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate what relationship, if any, exists

between a part-time faculty member’s self-reported perceptions of the quality of a peer-

mentoring relationship with instructor confidence, institutional loyalty, and student

satisfaction. Part-time instructors at a large, mid-western, Christian university served as

the participants for this study. The University has developed and implemented an

institutional mentoring program whereby part-time faculty members are mentored by

other part-time faculty. As such, this institution was uniquely situated to provide insight

into these previously stated relationships. More specifically, this study helped to answer

the following question: “Is peer-to-peer mentoring an effective means to support part-

time faculty, bolster confidence, increase institutional loyalty and consequently, produce

students who are satisfied that they received the best education and preparation?”

Assumptions

During the course of designing this investigation, I made several assumptions

regarding mentoring and its benefits as well as the effectiveness of peer-to-peer

mentoring over other forms of mentoring. Literature and studies suggest that mentoring is

a positive intervention that results in both personal and professional growth and

satisfaction among first-year teachers at the elementary and secondary levels (Darling-

Hammond, 2003; Edwards, 2000). This study assumes that the mentoring of part-time

faculty members at the post-secondary level will have similar results.

My review did not find any research that investigated the relationship between

peer mentoring among part-time faculty members. Consequently, this study assumes that

10

mentoring has not been widely practiced as a means of including part-time faculty

members in the teaching and learning community of post-secondary institutions.

Another key assumption made by this study is the belief that part-time instructors

are keenly interested in personal and professional development. They desire increased

opportunities to be included and to improve their teaching effectiveness. Part-time faculty

members are willing to invest the necessary time and energy to be actively involved in a

mentoring relationship, which could possibly lead to increased instructor confidence,

institutional loyalty, and student satisfaction.

Research Questions

This study sought to determine what relationship exists between a part-time

faculty member’s self-reported perceptions of the quality of a peer-mentoring experience

and several dependent variables: instructor confidence, institutional loyalty, and student

satisfaction. The primary research question was, “What relationship does peer-to-peer

mentoring have to instructor confidence, institutional loyalty, and student satisfaction

among part-time instructors in the University’s School of Business?” From this

overarching question, the following three research questions were identified.

Research Question 1

Is a part-time faculty member’s self-reported perception of the quality of a peer-

mentoring experience related to his or her degree of instructor confidence?

Research Question 2

Is a part-time faculty member’s self-reported perception of the quality of a peer-

mentoring experience related to his or her degree of institutional loyalty?

11

Research Question 3

Is a part-time faculty member’s self-reported perception of the quality of a peer-

mentoring experience related to his or her students’ satisfaction with the quality of the

learning experience as measured by a student evaluation of teaching/end-of-course form?

Theoretical Framework

Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory served as the main theoretical

framework for this dissertation. The foundation of social cognitive theory rests on the

premise that an individual’s thoughts, actions, and emotions influence his or her behavior

and that these three constructs are impacted and changed through reciprocal, social

relationships (Bandura, 1989). Mentoring, a primary focus of this study, occurs in the

context of personal relationships and within the social environment. This approach to

personal and professional growth and development makes social learning theory an

appropriate theoretical framework for this dissertation. According to social cognitive

theorists, learning is a “social process” (Zins, Boodworth, Weissberg, & Walberg, 2004,

p. 3).

Bandura’s (1989) social cognitive theory postulates that human beings have a

superior ability to learn vicariously, that is to say, we have the ability to learn from the

successes and mistakes of others. This aspect of social learning theory is critical. Bandura

believes that if we learned only from our own personal experiences, “the process of

cognitive and social development would be greatly retarded, not to mention exceedingly

tedious and hazardous” (p. 21). By observing others, we are able to extend our own skills

and conceptual knowledge. Bandura believes that we draw upon personal experiences as

well as the experiences of others who are “well-informed on the matters of concern” in

12

order to develop our own competency (p. 13). In fact, social learning theory emphatically

states that the most valuable knowledge is imparted socially. Typically, this vicarious

learning generates “new instances of behavior that go beyond what they have seen or

heard” (p. 25).

In fact, the attainment of these goals and increasing mastery of a particular skill

set results in what social learning theorists call self-efficacy (Bandura & Schunk, 1981).

According to Bandura (1989), “When people aim for and master valued levels of

performance, they experience a sense of satisfaction” (p. 48). Social learning theory

supports mentoring as an important means to convey knowledge and skill to another

person. Bandura claims that “knowledge and reasoning skills are best gleaned from those

who are highly knowledgeable and skilled” (p. 13).

Typically, an individual who is successful within an institution believes that the

work he or she does is important and valuable (Murray, 1991). According to Levinson,

Darrow, Klein, Levinson, and McKee (1978), a mentor is someone who takes a special

interest in helping to ensure that an individual develops into a successful professional.

Mentoring is a trusting, social relationship, which exists between a mentor, who is

experienced and successful, and a protégé, who is less skilled and experienced. The

purpose of a mentoring relationship is to develop confidence and competency. Mentors

can be helpful as they act as a counselor and guide in order to provide direction on how to

become a leader in their chosen vocation (Tobin, 1998).

This dissertation seeks to determine what relationship peer mentoring has with the

mentee’s confidence as an instructor, his or her institutional loyalty, and finally student

satisfaction scores. Bandura (1989) clearly believes that an influential social relationship,

13

such as mentoring, can result in increased confidence and personal satisfaction. This

study suggests that in addition to these outcomes, a socially influential relationship, such

as mentoring, will also result in increased commitment and loyalty to the organization.

Moreover, this study also examines if the increased confidence and loyalty of faculty

members are also notable in higher levels of satisfaction recorded by students with their

learning experience.

Bandura’s (1989) social learning theory supports the conclusion that an influential

relationship, like mentoring, results in greater confidence and loyalty. But Bandura’s

theory addresses only how one learns. It does not address what ramifications such

learning will have on the organization, its leadership, employees, or consumers. We have

already seen, through the literature, that a social learning strategy, like mentoring, would

likely result in higher levels of confidence and organizational loyalty among employees.

Because part-time instructors work in the organizational context of a university or

college, Bandura’s theory needs to be extended to address the results those twin outcomes

would have on the students of these employees or the organization’s “consumer.” This is

what System 4 Management Theory (Likert, 1961, 1967) does. The System 4

management strategy, which Likert calls participative group, will generally result in high

levels of trust, which in turn leads to higher levels of confidence and loyalty among

employees. This confidence and commitment to group and organizational goals results in

a high performing organization. It seems logical to assume that when organizational goals

are met, not only will the employees experience satisfaction but the recipients of the

organization’s services (i.e., students) will as well.

14

As the name implies, Likert hypothesized that there are four systems of

management. High functioning and high performing organizations have leaders who

operate using the fourth system, which Likert (1967) refers to as Participative Group.

System 1, which Likert (1961) labeled as exploitive, is characterized by a complete lack

of trust and the use of coercion and fear to achieve goals. The opposite set of behaviors

and skills is where we find System 4 or the participative-group function. Likert (1967)

maintains that high trust levels, mutual respect, high levels of participation, and a

commitment to individual, group, and organizational goals are characteristics of this

fourth system. Table 1 illustrates this continuum.

Table 1

Likert’s System 4 Management Theory

Trust

Motivation

Interaction

System 1:

Exploitive/Authoritative

Distrust

Fear/Punishment

Little interaction

System 2:

Benevolent/Authoritative

Cautious Trust

Reward/Punishment

Little interaction

System 3:

Consultative

Incomplete Trust

Reward/Punishment

and Involvement

Moderate

interaction

System 4:

Participative-Group

Complete Trust

Participation and

Improvements

Extensive

interaction

Note. From A Faster Learner’s Guide to Leadership: Rensis Likert, by D. Richards, n.d.

Retrieved July 30, 2009, from http://www.odportal.com/leadership/fastlearner/likert.htm

The most effective managers and organizations operate using this fourth system.

This fourth generation of management theory emphasizes supportive behavior on the part

15

of managers and team members. The function of supportive behavior is to increase and

maintain each individual’s sense of worth and value to the organization. Likert (1967)

states that when the organization engages in supportive behavior, “the group is eager to

help each member develop to his full potential” (p. 167). One result of this supportive

culture is a high level of peer loyalty, success in achieving organizational goals, and

effort on the part of team members to coach, train, encourage, and motivate each other

(Likert, 1967).

This dissertation actually modifies Likert’s theory by postulating that when social

learning occurs in the form of peer mentoring, members of the organization experience

increased trust levels and increased opportunities for participation and interaction. This

results in confident and loyal employees. These confident and loyal employees have a

positive impact on the organization’s customers, the students, which, in turn, results in

higher levels of students satisfied with the instruction they have received.

This dissertation tested whether peer mentoring was an effective supportive

behavior strategy and tool that managers could utilize to facilitate the achievement of

System 4 outcomes such as high employee confidence, institutional loyalty, and high

levels of customer (i.e., student) satisfaction. I assumed that a high performing

organization, by default, would have customers who are satisfied with the product and

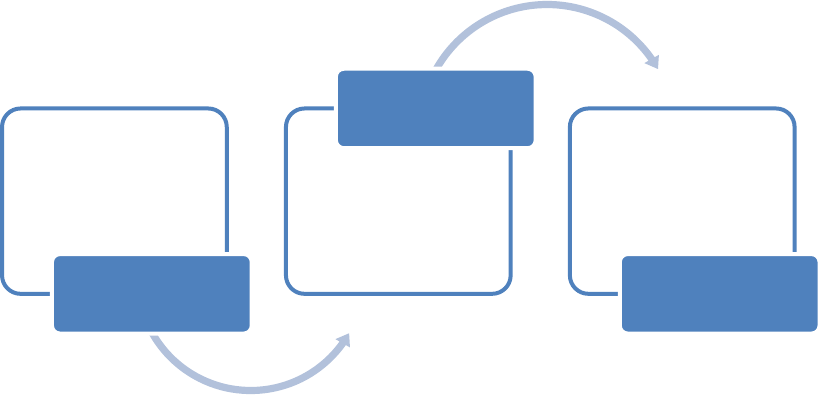

services they received. Figure 1 illustrates this process and outcome.

Significance of the Study

As one of five regional coordinators of faculty services for Spring Arbor

University, I have spent the past 12 years in the trenches, beside the most gifted and

committed part-time faculty members. Adjuncts desire to grow and develop in their roles

16

Figure 1. Peer mentoring process and outcomes.

as faculty members; they are willing and able to join the larger, scholarly community.

They only lack the avenue to do so. This study is important because it will assist those in

similar leadership roles to lead this army of part-time laborers more effectively.

This study is important because the results could be used to inform the

University’s leaders, and those of similar schools, how best to support the large number

of adjuncts who teach in their programs. This University relies heavily on part-time

faculty members to fill teaching appointments. As the research suggests, this was an

intentional decision based on two elements—cost effectiveness and the belief that

practitioner professors were uniquely qualified to teach adult learners.

To those who work in the field of higher education, the significance of this study

is apparent. As reliance on part-time faculty appointments increases, so do the questions.

The problems are real, the debate rages; yet I was not able to locate any research

designed to investigate the relationship between peer-to-peer mentoring and instructor

confidence, institutional loyalty, and student satisfaction. It is evident that part-time

• Peer Mentoring provides

support through

• Social Learning

• Training, coaching

• Encouragement

• Motivation

Results in increased

confidence

• in Adult learning theory

• in Effective teaching methods

• in content knowlege

• in knowledge of univesity

polices and procedures

Results in increased

loyalty

• Faculty more committed to

university mission

• Faculty more likely to accept

teaching assignments

• Faculty more experienced

• Less turn over

Results in more

satisfiied students

• Increased satisfaction with

learning experiences

• Increased student satisfaction

scores

High Performing

Organization

17

faculty appointments are not going away. Evidence is to the contrary; part-time faculty

members are here to stay and our reliance on them is increasing. Consequently, it is

essential that universities and administrators wrestle with the issues in order to answer the

question, “Can a part-time faculty member deliver quality instruction and contribute to

the community of learners as well as their full-time, tenured counterparts?” Moreover, “is

peer-to-peer mentoring an effective means to achieve that outcome?”

General Research Methodology

Since this study sought to collect data “after the fact,” an ex post facto research

design was used to gather data from the part-time faculty members in the University’s

College of Adult and Professional Studies. The group surveyed was a convenient sample

representative of part-time faculty members teaching at this University at the present and

in the future. The survey collected demographic information and data to measure

instructor confidence and institutional loyalty. Moreover, one section of the survey was

designed to elicit the participants’ perceptions of the fidelity or quality of their peer-

mentoring experience. I also reviewed historical data from the University’s End of

Course Survey forms in order to determine the measure for student satisfaction. Once the

survey responses were collected, general linear regression models were generated in

order to test the research questions and to determine whether the findings were

significant.

Limitations

Several factors limit the ability to infer and generalize from the study’s findings.

Since an ex post facto research design was used, random manipulation of the independent

18

and predictor variables was not possible. Therefore, it is impossible to conclude, with any

certainty, the predictor variable was the cause of the significant relationships rather than

some other spurious variable. Adequate safeguards do not exist to infer causation (Ary,

Jacobs, & Sorenson, 2010). Broadly generalizing causation from this study’s findings

would be inappropriate.

The response rate (25%) also affects the ability to generalize from the study’s

findings. For example, some responses were not included in the analysis because the

participant had not received mentoring or failed to answer all the questions on a particular

subscale. Of the 147 who responded, only 63 (or 43%) had received mentoring. In

addition, some of the hypotheses stated that those with a part-time mentor would do just

as well or better than those mentored by a full-time administrator counterpart. Cases

available to test the hypotheses related to type of mentor were further reduced. For

example, of the 63 who had received mentoring, only 31 (or 49.2%) were mentored by

another part-time faculty member. When you consider those mentored by a full-time

faculty member (n = 23 or 36.5%) or an administrator (n = 8; 12.7%) the cases available

for analysis are even less. While the findings will provide helpful information to the

University’s leadership, broadly generalizing or inferring causation from the results

would be inappropriate.

Finally, while the instrument used to collect data on instructor confidence and the

fidelity of the mentoring program variables was developed using multiple strategies to

increase the estimates of its validity and reliability, the fact remains that these two

subscales lacked extensive testing and re-testing to increase validity and reliability. The

initial estimates of reliability, the ability of the instrument to be consistent, were adequate

19

(α

c

=.937 for the Instructor Confidence subscale and α

c

=.817 for Fidelity of Mentoring

Experience Subscale). And while key strategies, such as field testing, expert judges,

logical and concrete validity were used to increase the estimated validity of these two

subscales, more testing and analysis are needed.

Delimitations

I elected to limit the scope of this study to part-time instructors who teach in the

School of Business at a large, private, mid-western, Christian university. (The School of

Business comprises almost 80% of the student enrollment and represents the largest

sector of part-time faculty.) I selected this University because it is a large, Christian

university that offers adult degree programs, uses part-time faculty members almost

exclusively to staff classroom-teaching assignments, and has an institutional peer-

mentoring program. In addition, this University utilizes end-of-course survey forms as a

means of assessing student satisfaction.

This study explored the relationship of peer-to-peer mentoring and an individual

part-time faculty member’s confidence level, institutional loyalty, and degree of students’

satisfaction with the instructor’s competence. I did not attempt to measure or evaluate the

overall quality of instruction that part-time instructors provide. Conclusions regarding the

institution’s effectiveness as a teaching community were beyond the scope or interest of

this study.

Definition of Terms

I have provided the following definition of terms in order to ensure consistency

and clarity of communication concerning the key constructs involved in the study. The

20

independent and dependent variables are operationally defined, and definitions are

provided for other important and frequently used terms.

Andragogy: Refers to the teaching philosophy, first espoused by Malcolm

Knowles, which delineated the differences between traditional students and adult

learners. Different from pedagogy (which is teacher driven), andragogy is student driven

and recognizes that adult learners bring the following characteristics into the classroom:

motivation, discipline, life experience, and a desire for practical application that links

theory to practice (Knowles & Associates, 1984).

College of Adult and Professional Studies (CAPS): Refers to the University’s

department that develops and implements programs designed specifically for the working

adult. Such programs are typically based on principles of andragogy and have the

following common characteristics: lock-step cohort design, modules offered in 5- or 6-

week increments, weekly classes meet for 4 hours, accelerated curriculum design and

course learning measured by higher order thinking skills, and the students’ ability to

apply learning to work and personal settings (Bash, 2005).

Fidelity Measure: Refers to the extent to which the peer-mentoring program

adhered to the prescribed protocol (Mowbray, Holter, Teague, & Bybee, 2003).

Considering the fidelity of any intervention or treatment variable is important to ensure

that experiences similar and that any significant differences are documented. In the case

of this study, the prescribed protocol refers to the recommended elements of quality

mentoring programs as delineated in the scholarly literature and not the mentoring

program requirements as outlined by the University.

21

Institutional Loyalty: A self-reported measure in which a part-time instructor

indicates his or her degree of positive regard toward the organization (Ashforth, Spencer,

& Corley, 2008) as well as how much the part-time instructor believes the University

values his or her contribution and well-being (LaMastro, 2000). Frequently one finds the

term organizational commitment used almost synonymously with institutional loyalty.

Consequently, I use these terms interchangeably. Institutional loyalty was measured using

a previously validated organizational commitment scale (Allen & Meyer, 1990; Meyer &

Allen, 1988).

Instructor Confidence: A self-reported measure in which a part-time instructor

indicates his or her level of confidence with the course content (Donaldson, 1988;

Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2005), adult learning methodology (Bash, 2005; Fleming

& Garner, 2009; Galbraith, 2004; Merriam, 2001), and institutional policies and

procedures (Wilson & Elman, 1990). A researcher-developed questionnaire was used to

measure this variable.

Part-time Instructor: The instructional faculty who are not contracted full-time

with the University. Typically, a part-time instructor’s teaching load is less than 50% of

the load carried by full-time, contracted faculty. Contracts for part-time instructors are

issued on an individual teaching assignment basis. Part-time instructors do not have

dedicated office space or benefits such as health insurance, retirement, sick days, etc.

(AAUP, 2006; Barnetson, 2001; Fulton, 2000; Magner, 1999).

Peer-to-Peer Mentoring: Experiences of adjunct faculty who have been mentored,

coached, and guided by other, part-time instructors (Kram & Isabella, 1985; Routman,

22

2000). The researcher-developed fidelity subscale was used to gather data on this self-

reported measure.

Student Satisfaction: The student self-reported perception of the instructor’s

effectiveness in terms of overall course quality, teaching skill, and availability (Appleton-

Knapp & Krentler, 2006; Kelly, Ponton, & Rovai, 2007; Sproule, 2002). An aggregate of

the University’s end-of-course survey forms was used to measure this variable.

Organization of the Study

This chapter provided the reader with the history and background of the problem.

I offered social learning theory and Likert’s System 4 Management Theory as appropriate

theoretical frameworks for the study. The research problem and general research

questions were given along with operational definitions of key terms and variables.

Chapter 2 begins with a review and analysis of relevant literature. Literature

relevant to the phenomenon of rise in use of part-time instructors is noted. The concerns

and benefits regarding the use of a large number of part-time instructors are investigated.

The literature review also examines the roots of mentoring and its use by post-secondary

institutions to train and orientate new faculty members. The concept of peer-to-peer

mentoring is investigated; this includes a review of studies and other relevant literature

that examine the benefits of using peer mentors as opposed to non-peer mentors.

As universities continue to turn to the use of part-time faculty, the issues of

availability and loyalty arise. New phrases such as “Roads Scholars” and “Freeway

Faculty” have entered the post-secondary institutions’ vocabulary. I examined this trend

and its relationship to institutional loyalty. Elements that contribute to instructor

23

confidence and its role in teaching effectiveness are shared. Also, student satisfaction as a

measure of instructor effectiveness was investigated.

Chapter 3 provides the reader with detailed information regarding the research

design. This includes information on the sample and selection criteria. This chapter also

outlines the data collection plan and includes information on the survey instruments and

other tools used to gather data related to the study. Chapter 4 describes the setting of the

research and the peer-mentoring program, which comprises the “intervention” used in the

collection and analysis of the data. The data analysis plan will be explained. Chapter 5

provides the results of the study, and Chapter 6 discusses the conclusions and

recommendations, including thoughts for further research.

24

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP), the Association of

American Colleges and Universities (AACU), and others have expressed concern that

universities are too dependent on part-time faculty members, and this dependency

threatens the academic integrity of the American academy (AAUP, 2006; Benjamin,

2002). This chapter reviews literature as it relates to the previously mentioned issues.

First, I review the historical perspective, which includes statistics related to the

rising use of part-time faculty members as well as some of the reasons for this continuing

trend. I discuss critical issues surrounding the debate in the rise in use of part-time faculty

members. As outlined in Chapter 1, instructor confidence, institutional loyalty, and

student satisfaction are important issues related to this dependence on part-time faculty

members and will be discussed in section two. Finally, the practice of mentoring, which

includes information related to peer mentoring, will be examined in general with a closer

look at the peer mentoring. This literature review will assist in building a framework to

help answer the research question, “What is the relationship between peer-to-peer

mentoring and a part-time faculty member’s instructor confidence, institutional loyalty,

and student satisfaction scores?”

25

Part-time Faculty

The Rise in Use of Part-time Faculty

The use of part-time faculty is not the sole purview of the modern post-secondary

institution. As far back as the middle ages through the post-Civil War era, part-time

faculty were used in order to provide expertise that was lacking among full-time faculty

(Jacobs, 1998). Schuster and Finkelstein (2006) believe that “faculty is central to the

well-being of the academy” (p. 3). The powerful union, the American Association of

University Professors (AAUP), could not agree more. The AAUP asserts, “The integrity

of higher education rests on the integrity of the faculty profession” (AAUP, 2003, p. 69).

Bowen and Schuster (1986) state the matter plainly; there can be no question, “The main

duty of every institution of higher education is to place a competent faculty” (p. 3).

This is the central debate over the use of part-time faculty members reduced to its

most fundamental elements. The use of part-time faculty has come a long way since

priests and scholars roamed the European countryside, visiting monasteries and

universities to study and offer expertise (Toutkoushian & Bellas, 2003). These authors

assert that a century of progress has been reversed because the American academy has

come to over-rely on part-time faculty members (Bowen & Schuster, 1986).

Consider that in 1960, according to Bowen and Shuster (1986), 35% of faculty

appointments were for part-time faculty members. Benjamin (2002) asserts that use of

part-time appointments over full-time ones rose 103% between the years of 1975 and

1995. In 1998, the AAUP claimed that the 25 years from 1973 to 1998 saw a substantial

increase in the number of universities relying on part-time appointments.

26

In 1998, university administrators gave 43% of all faculty appointments to part-

timers. In 2004, this trend and reliance on part-time faculty has remained consistent,

increasing by several percentage points, from 43 to 49.3% (Snyder & Dillow, 2012).

Leatherman (2000a), in an article entitled, “Part-timers Continue to Replace Full-timers

on College Faculties,” observed that adjuncts comprise nearly 50% of the professoriate.

This is consistent with more recent figures from the AAUP that estimates that 48% of

faculty in U.S. institutions are part-time, non-tenure-track faculty (AAUP, 2009). Many

believe these numbers are “gravely underestimated” (Wilson, 1999, p. 15).

In an interview conducted by Rice (2004), Finkelstein and Schuster agreed that

the American professoriate is “to a considerable degree, a part-time profession. . . .

Faculty members in the U.S. are currently split close to 50-50 between part and full-time”

(p. 28). Some universities, particularly the University of Phoenix, use exclusively part-

time faculty members (Feldman & Turnley, 2001).

This reliance grew, not only in 4-year colleges, but in community colleges and

private institutions as well. Between 1972 and 1977, both private and public universities

experienced a sharp decline in their financial support (Ivey et al., 2005). As a result, since

the 1980s, the majority of new hires were part-timers and not tenure-track faculty. In

2003, the AAUP (2006) stated that full-time, tenure-track faculty positions comprised

only 24% of the faculty labor force. Ivey et al. (2005) compared this to 1969 when 96.7%

of new hires were for full-time, tenure-track positions.

When one reviews the literature, which seems replete with dire warnings

regarding the consequences associated with using part-time faculty, one has to wonder,

“Why does the trend continue?” There are four key reasons why universities continue to

27

depend on part-time faculty: the G.I. Bill, money, flexibility in scheduling, and supply

and demand.

The G.I. Bill

At the end of World War II, almost 30 million American military personnel

employed by the war efforts were thrust back into American life. This number comprised

almost one-quarter of the entire American workforce. Recruiting and drafting efforts took

millions of young people out of school and sent them to war (Mosch, 1975). The

resulting influx of millions, coupled with an educational deficit, set the stage for an

unprecedented domestic crisis (Mosch, 1975).

As a result, the G.I. Bill, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, provided educational

benefits, among other provisions, to World War II veterans (Toby, 2010). By the time the

bill’s initial provisions ended in 1956, over 7.8 million of the 16 million World War II

veterans took advantage of these resources; in 1947, almost half of U.S. college students

were veterans (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d.). Universities worried about the

educational consequences of admitting large numbers of veterans; they could not expand

facilities or faculty fast enough to accommodate this influx of students (Toby, 2010).

In 1952 and again in 1966, this bill was extended to offer education, grants, and

job-training skills to more veterans (Mosch, 1975). Twenty years later, baby boomers

(who were coming of age) flocked to universities in ever-increasing numbers, which

resulted in another boon and even more increased enrollments (Bowen & Schuster,

1986). This increase in enrollment, along with an increase in the number of qualified,

full-time faculty who were retiring, resulted in an unprepared university system turning to

part-time faculty members (R. Smith, 1980).

28

The Money Factor

Like any business, educational administrators have had to look for ways to

increase revenues and decrease costs. So it comes as no surprise that, without exception,

most agree that this rise in use of part-time faculty over the past 40 years is primarily due

to Cherchez L’ Argent, or the money motive (Noble, 2000). In 1980, federal and state

governments subsidized 46% of the cost of higher education; by 2003, the percentage had

decreased to 35% (Lerber, 2006). In addition, federal financial aid polices became more

restrictive (German, 1996). Because of this decline in government spending, colleges and

universities had to cut costs to make ends meet (Ochoa, 2011). By not hiring full-time,

tenure-track faculty, universities were able to realize a cost savings. Once a full-time

position was cut, the faculty dollars saved were rarely seen again. Instead, universities

began spending whatever surplus funds were realized on the school’s physical

infrastructure and technology (Ochoa, 2011).

Consequently, the use of part-timers mushroomed into a source of cheap labor

(Magner, 1999). In fact, Noble (2000) estimates that the use of adjunct faculty results in

an almost 42% net gain for the bottom line of universities. Noble (2000) states, “Lower

faculty status is associated with the production of a larger net gain” (p. 94).

Generally, universities pay part-time faculty members less than full-time faculty

and these institutions rarely provide benefits or job advancement opportunities

(Barnetson, 2001; Fulton, 2000; Magner, 1999; Ochoa, 2011). Marcus (1997) observed,

“Because they are so cheap, institutions really come to depend on them” (p. 10). Terry-

Sharp (2001) surveyed 421 anthropology departments on their utilization of part-time