MICHAEL BRYSON AND ARPI MOVSESIAN

From the Song of Songs to

Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden

Love and its Critics

To access digital resources including:

blog posts

videos

online appendices

and to purchase copies of this book in:

hardback

paperback

ebook editions

Go to:

hps://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611

Open Book Publishers is a non-prot independent initiative.

We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing

high-quality academic works.

Love and its Critics

From the Song of Songs

to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden

Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2017 Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC

BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt

the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the

authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Attribution should include the following information:

Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian, Love and its Critics: From the Song of Songs to

Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.

org/10.11647/OBP.0117

In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://

www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611#copyright

Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

by/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have

been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.

openbookpublishers.com/product/611#resources

Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or

error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

California State University Northridge has provided support for the publication of

this volume.

ISBN Paperback: 978–1-78374–348–3

ISBN Hardback: 978–1-78374–349–0

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978–1-78374–350–6

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978–1-78374–351–3

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978–1-78374–352–0

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0117

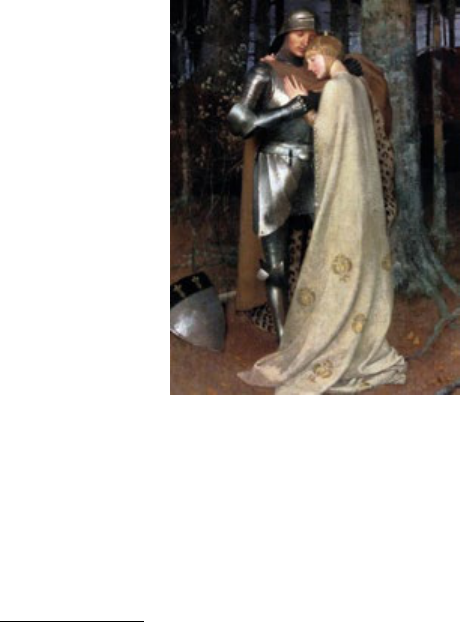

Cover image: Ary Scheffer, Dante and Virgil Encountering the Shades of Francesca da Rimini and

Paolo in the Underworld (1855), Wikimedia, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1855_

Ary_Scheffer_-_The_Ghosts_of_Paolo_and_Francesca_Appear_to_Dante_and_Virgil.jpg

All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), PEFC

(Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) and Forest Stewardship

Council(r)(FSC(r) certified.

Printed in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia

by Lightning Source for Open Book Publishers (Cambridge, UK)

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not, writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

—William Blake, “The Garden of Love”, Songs of Experience

Et si notre âme a valu quelque chose, c’est qu’elle a brûlé plus ardemment

que quelques autres.

—André Gide, Les Nourritures terrestres

Die Wissenschaft unter der Optik des Künstlers zu sehn, die Kunst aber

unter der des Lebens.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik

Contents

Acknowledgements ix

A Note on Sources and Languages x

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics 1

I. The Poetry of Love 1

II. Love’s Nemesis: Demands for Obedience 3

III. Love’s Critics: The Hermeneutics of Suspicion and the

Authoritarian Approach to Criticism

10

IV. The Critics: Poetry Is About Poetry 23

V. The Critics: The Author Is Dead (or Merely Irrelevant) 29

2. Channeled, Reformulated, and Controlled: Love Poetry from the

Song of Songs to Aeneas and Dido

37

I. Love Poetry and the Critics who Allegorize: The Song of Songs 37

II. Love Poetry and the Critics who Reduce: Ovid’s Amores and

Ars Amatoria

57

III. Love or Obedience in Virgil: Aeneas and Dido 77

IV. Love or Obedience in Ovid: Aeneas, Dido, and the Critics

who Dismiss

89

3. Love and its Absences in Late Latin and Greek Poetry 97

I. Love in the Poetry of Late Antiquity: Latin 97

II. Love in the Poetry of Late Antiquity: Greek 113

4. The Troubadours and Fin’amor: Love, Choice, and the Individual 121

I. Why “Courtly Love” Is Not Love 121

II. The Troubadours and Their Critics 136

III. The Troubadours and Love 165

5. Fin’amor Castrated: Abelard, Heloise, and the Critics who Deny 195

6. The Albigensian Crusade and the Death of Fin’amor in Medieval

French and English Poetry

215

I. The Death of Fin’amor: The Albigensian Crusade and its

Aftermath

215

II. Post-Fin’amor French Poetry: The Roman de la Rose 238

III. Post-Fin’amor English Romance: Love of God and Country

in Havelok the Dane and King Horn

275

IV. Post-Fin’amor English Poetry: Mocking “Courtly Love”

in Chaucer—the Knight and the Miller

280

V. Post-Fin’amor English Poetry: Mocking “Auctoritee”

in Chaucer—the Wife of Bath

286

7. The Ladder of Love in Italian Poetry and Prose, and the Reactions

of the Sixteenth-Century Sonneteers

295

I. The Platonic Ladder of Love 295

II. Post-Fin’amor Italian Poetry: The Sicilian School to Dante

and Petrarch

300

III. Post-Fin’amor Italian Prose: Il Libro del Cortegiano (The Book of

the Courtier)

330

IV. The Sixteenth-Century: Post-Fin’amor Transitions in

Petrarchan-Influenced Poetry

336

8. Shakespeare: The Return of Fin’amor 353

I. The Value of the Individual in the Sonnets 353

II. Shakespeare’s Plays: Children as Property 367

III. Love as Resistance: Silvia and Hermia 378

IV. Love as Resistance: Juliet and the Critics who Disdain 393

9. Love and its Costs in Seventeenth-Century Literature 421

I. Carpe Diem in Life and Marriage: John Donne and the

Critics who Distance

422

II. The Lyricist of Carpe Diem: Robert Herrick and the

Critics who Distort

445

10. Paradise Lost: Love in Eden, and the Critics who Obey 467

Epilogue. Belonging to Poetry: A Reparative Reading 501

Bibliography 513

Index 553

Acknowledgements

This book emerges from multiple experiences and perspectives:

teaching students at California State University and the University

of California; leaving a religious tradition, and leaving a country and

an entire way of life; extensive written and verbal conversations with

people from all over the world—from the Middle East, Africa, Sri

Lanka, Western Europe, the former Soviet Union, and the Asian Pacific

Rim; and finally, an attempt to understand what has happened to the

study of poetry, especially love poetry, in modern literary education.

Our thanks go out to Alessandra Tosi, Lucy Barnes and Francesca

Giovannetti at Open Book Publishers, who worked tirelessly with

us on the manuscript to make this book possible. Thanks are due

especially to Nazanin Keynejad, who read and commented upon the

first draft of this book, and to Modje Taavon, who provided valuable

insight into the similarities between the early modern European and

contemporary Middle Eastern cultures. Special thanks are also due to

Robert Bryson, Naomi Bryson, Heather Bryson, Alan Wolstrup, Steven

Wolstrup, Yeprem Movsesian, Ruzan Petrosian, Haik Movsesian,

and Edgar Movsesian, not only for their differing experiences and

perspectives, but for personal encouragement and support.

A Note on Sources and Languages

This book works with material that spans two thousand years and

multiple languages. Many, though by no means all, of the sources it

works with are from older editions that are publicly available online.

This is done deliberately in order to allow readers who may not be

attached to insitutions with well-endowed libraries to access as much of

the information that informs this work as possible, without encountering

paywalls or other access restrictions. It was not possible to follow this

procedure in all cases, but every effort has been made. Where the book

works with texts in languages other than English, the original is provided

along with an English translation. This is done in order to emphasize

that the poetic and critical tradition spans both time and place, reflecting

arguments that are conducted in multiple language traditions. This is also

done, frankly, to make a point about language education in the English-

speaking world, especially in the United States, where foreign-language

requirements are increasingly being questioned and enrollment figures

have declined over the last half-century—according to the 2015 MLA

report, language enrollments per 100 American college students stands

at 8.1 as of 2013, which is half of the ratio from 1960 (https://www.mla.

org/content/download/31180/1452509/EMB_enrllmnts_nonEngl_2013.

pdf, 37). Languages matter. Words matter. One of the arguments of

this book is that the specific words and intentions of the poets and the

critics matter; though English translation is necessary, it is not sufficient.

Quoting the original words of the poets and the critics is a way of giving

the authors their voice.

1. Love and Authority:

Love Poetry and its Critics

I

The Poetry of Love

Love has always had its critics. They range far and wide throughout

history, from Plato and the Neoplatonists, to the Rabbinic and Christian

interpreters of the Song of Songs, from the clerics behind the savage

Albigensian Crusade, to the seventeenth-century English Puritan

author William Prynne, who never met a joy he failed to condemn.

Love has never lacked for those who try to tame it for “higher”

purposes, or those who would argue that “the worst evils have been

committed in the name of love”.

1

At the same time, love has always

had its passionate defenders, though these have more often tended

to be poets—the Ovids, Shakespeares, and Donnes—than critics of

poetry. The relationship between the two—poets and critics—is one of

the central concerns of this book.

The story this book tells follows two paths: it is a history of love,

a story told through poetry and its often adversarial relationship to

the laws and customs of its times and places. But it is also a history

of the way love and poetry have been treated, not by our poets, but

by those our culture has entrusted with the authority to perpetuate the

understanding, and the memory, of poetry. This authority has been

1 Aharon Ben-Zeev and Ruhama Goussinsky. In the Name of Love: Romantic Ideology

and Its Victims (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 63.

© 2017 Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0117.01

2 Love and its Critics

abused by a tradition of critics and criticism over two thousand years

old, a tradition dedicated to reducing poetry to allegory or ideology,

insisting that the words of poems do not mean what they appear to mean

to the average reader. And yet, love and its poetry fight back, not just

against critics but against all the real and imagined tyrants of the world.

As we will see in the work of Shakespeare, love stands against a system

of arranged marriages in which individual desires are subordinated to

the rule of the Father, property, and inherited wealth. Sometimes, as in

Milton’s Paradise Lost, love will even stand against God himself. As Dante

demonstrates with his account of Paolo and Francesca, love lives the truth

that Milton’s Satan speaks: it is better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.

What is this love? And how is it treated in our poetry? Ranging from

the ancients to the early moderns, from the Bible to medieval literature,

from Shakespeare to the poetry of the seventeenth century and our own

modern day, the love presented here is neither exclusively of the body,

nor exclusively of the spirit. It is not merely sex—though some critics

have been eager to dismiss it in just this way. Neither, however, is it

only spiritual, intellectual, emotional, or what is popularly referred to

as Platonic. The love this book considers, and that so much of our poetry

celebrates, is a combination of the physical and the emotional, the sexual

and the intellectual, the embodied and the ethereal. Above all, it is a

matter of mutual choice between lovers who are each at once Lover and

Beloved. Often marginalized by, and in opposition to church, state, and

the institutions of marriage and law, this love is what the troubadour

poets of the eleventh and twelfth centuries referred to as fin’amor.

2

It is

anarchic and threatening to the established order, and a great deal of

cultural energy has gone into taming it.

Fin’amor—passionate and mutually chosen love, desire, and regard—

has been invented and reinvented over the centuries. It appears in

Hellenistic Jerusalem as a glimpse back into the age of Solomon, then

fades into the dim background of Rabbinical and Christian allegory. It

2 This working definition is at odds with much, though by no means all, of the

specialized scholarship on troubadour poetry. One of the major contentions of this

book is that too much of the work by specialists in many literary fields minimizes,

reinterprets, or outright ignores the human elements of love and desire in poetry,

a situation which scholars like Simon Gaunt and Sarah Kay admit has gone too

far. See “Introduction”. In Simon Gaunt and Sarah Kay, eds. The Troubadours: An

Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 6.

3

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

is revived in France, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, by poets and

an unusual group of Rabbis, only to fade once again, betrayed by later

poets writing under the twin spells of Neoplatonism and Christianizing

allegory. These later poets radically reshape the ideas of love expressed

in the poems of medieval Provençe and the ancient Levant, writing in

what Dante calls the “sweet new style” (dolce stil novo) that changed love

into worship, men into idolators, and women into idols. The influence of

their verse is still observable in the English poetry of Philip Sidney two

hundred years after the death of Petrarch, the dolce stil novo’s high priest.

Subsequently, writers such as Shakespeare, Donne, Herrick, and Milton

re-invent the love that had almost been lost, putting a new version of

fin’amor on the stage and on the page, pulling it back into the light and

out of the shadows of theology, philosophy, and law. For better, or for

worse, fin’amor has been with us ever since.

II

Love’s Nemesis: Demands for Obedience

Running parallel with the tradition of love poetry is a style of thought

which argues that obedience, rather than passion, is the prime virtue of

humankind. Examples of obedience demanded and given are abundant

in our scriptures, such as the injunction in Genesis against eating from

the Tree of Knowledge; in our poetry, such as the Aeneid’s portrayal

of Aeneas rejecting Dido in obedience to the gods; and even in our

philosophy, as in Aristotle’s distinction between free men and slaves:

“It is true, therefore, that there are by natural origin those who are truly

free men, but also those who are visibly slavish, and for these slavery is

both beneficial and just”.

3

Such expectations of obedience often appear

in the writing of those who argue that human law derives from divine

law. Augustine argues that though God did not intend that Man should

have dominion over Man, it now exists because of sin:

3 “ὅτι μὲν τοίνυν εἰσὶ φύσει τινὲς οἱ μὲν ἐλεύθεροι οἱ δὲ δοῦλοι, φανερόν, οἷς

καὶ συμφέρει τὸ δουλεύειν καὶ δίκαιόν ἐστιν”(Aristotle. Politics, ed. by Harris

Rackham [Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press],

1932, 1255a, 22, 24). Unless otherwise noted, all translations are ours.

4 Love and its Critics

But by nature, as God first created us, no one was a slave either of man or

of sin. In truth, our present servitude is penal, a penalty which is meant

to preserve the natural order of law and forbids its disturbance; because,

if nothing had been done contrary to that law, there would have been

nothing to restrain by penal servitude.

4

Nearly a millennium later, Thomas Aquinas argues from a similar

perspective: “The order of justice requires that inferiors obey their

superiors, for otherwise the stability of human affairs could not be

maintained”.

5

Even a famous rebel like Martin Luther directs ordinary

citizens to obey the law God puts in place: “No man is by nature Christian

or religious, but all are sinful and evil, wherefore God restrains them all

through the law, so that they do not dare to practice their wickedness

externally with works”.

6

According to John Calvin, absolute obedience

is due not only to benevolent rulers, but also to tyrants. Wicked rulers

are a punishment from God:

Truthfully, if we look at the Word of God, this will lead us further. We

are not only to be subject to their authority, who are honest, and rule by

what ought to be the gift of God’s love to us, but also to the authority

of all those who in any way have come into power, even if their rule is

nothing less than that of the office of the princes of the blind. […] at the

same time he declares that, whatever they may be, they have their rule

and authority from him.

7

4 “Nullus autem natura, in qua prius Deus hominem condidit, seruus est hominis

aut peccati. Verum et poenalis seruitus ea lege ordinatur, quae naturalem ordinem

conseruari iubet, perturbari uetat; quia si contra eam legem non esset factum, nihil

esset poenali seruitute coërcendum” (Augustine of Hippo. De Civitate Dei [Paris:

1586], Book 19, Chapter 15, 250, https://books.google.com/books?id=pshhAAAAcA

AJ&pg=PA250).

5 “Ordo autem iustitiae requirit ut inferiores suis superioribus obediant, aliter

enim non posset humanarum rerum status conservari” (Thomas Aquinas. Summa

Theologiae: Vol. 41, Virtues of Justice in the Human Community, ed. by T. C. O’Brien

[Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006], 2a2ae. Q104, A6, 72).

6 “Nun aber kein Mensch von Natur Christ oder fromm ist, sondern sie allzumal

Sünder und böse sind, wehret ihnen Gott allen durchs Gesetz, daß sie ihre Bosheit

nicht äußerlich mit Werken nach ihrem Mutwillen zu üben wagen” (Martin Luther.

Von Weltlicher Obrigkeit [Berlin: Tredition Classics, 2012], 10).

7 Verùm si in Dei verbum respicimus, longius nos deducet, ut non eorum modò principú imperio

subditi simus, qui probè, & qua debét fide munere suo erga nos defungútur: sed omnium qui

quoquo modo rerum potiuntur, etiamsi nihil minus praestét quàm quod ex officio principum.

[…] simul tamen declarat, qualescunque sint, nonnisi à se habere imperium.

5

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

For these thinkers, obedience is the prime duty of humankind, because

it is ultimately in service to the God who established all authority in the

first place. To be obedient is therefore to be pleasing to God.

Such demands for obedience are ancient, and widespread, but

resistance has its own long tradition. Étienne de La Boétie, the sixteenth-

century author, judge, and friend to Michel Montaigne, argues that

human beings have long become so used to servitude that they no

longer know how to be free:

It is incredible how a people, when it becomes subject, falls so suddenly

and profoundly into forgetfulness of its freedom, so that it is not possible

for them to win it back, serving so frankly and so happily that it seems, at

a glance, that they have not lost their freedom but won their servitude.

8

La Boétie maintains that obedience has become so engrained in most

people, that they regard their subjection as normal and necessary:

They will say they have always been subjects, and their fathers lived the

same way; they will think they are obliged to endure the evil, and they

demonstrate this to themselves by examples, and find themselves in the

length of time to be the possessions of those who lord it over them; but

in reality, the years never gave any the right to do them wrong, and this

magnifies the injury.

9

This “injury” leads La Boétie to reject the idea of natural obedience,

proposing instead a model through which he accuses “the tyrants”

(“les tyrans”) of carefully inculcating the idea of submission into the

populations they dominate:

Jean Calvin. Institutio Christianae Religionis (Geneva: Oliua Roberti Stephani, 1559),

559, https://books.google.com/books?id=6ysy-UX89f4C&dq=Oliua+Roberti+Stepha

ni,+1559&pg=PA559

8 “Il n’est pas croyable comme le peuple, dès lors qu’il est assujetti, tombe si soudain

en un tel et si profond oubli de la franchise, qu’il n’est pas possible qu’il se réveille

pour la ravoir, servant si franchement et tant volontiers qu’on dirait, à le voir, qu’il a

non pas perdu sa liberté, mais gagné sa servitude” (Étienne de La Boétie. Discours de

la Servitude Volontaire [1576] [Paris: Éditions Bossard, 1922], 67, https://fr.wikisource.

org/wiki/Page:La_Boétie_-_Discours_de_la_servitude_volontaire.djvu/73).

9 “Ils disent qu’ils ont été toujours sujets, que leurs pères ont ainsi vécu; ils pensent

qu’ils sont tenus d’endurer le mal et se font accroire par exemple, et fondent eux-

mêmes sous la longueur du temps la possession de ceux qui les tyrannisent; mais

pour vrai, les ans ne donnent jamais droit de mal faire, ains agrandissent l’injure”

(ibid., 74–75, https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:La_Boétie_-_Discours_de_la_

servitude_volontaire.djvu/80).

6 Love and its Critics

The first reason why men willingly serve, is that they are born serfs and

are nurtured as such. From this comes another easy conclusion: people

become cowardly and effeminate under tyrants.

10

[…] It has never been

but that tyrants, for their own assurance, have made great efforts to

accustom their people to them, [training them] not only in obedience

and servitude, but also in devotion.

11

Two centuries later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau raises his voice against the

authority of “les tyrans”, arguing that liberty is the very basis of humanity:

To renounce liberty is to renounce being a man, the rights of humanity,

even its duties. […] Such a renunciation is incompatible with the nature

of man, and to remove all liberty from his will is to remove all morality

from his actions. Finally, it is a vain and contradictory convention to

stipulate on the one hand an absolute authority, and on the other an

unlimited obedience.

12

But what Rousseau calls a renunciation of liberty, framing it as a

conscious act, La Boétie presents as something that is done to rather than

done by average men and women: “they are born as serfs and nurtured as

such”. In the latter’s view, it is those in authority who “nurture” (raise,

nourish, even instruct) their populations into the necessary attitudes of

what Rousseau will later call une obéissance sans bornes.

Such “nurture” performs a pedagogical function, teaching men and

women to think their bondage is natural: for La Boétie, “it is certain

that custom, which in all things has great power over us, has no greater

10 “[L]a première raison pourquoi les hommes servent volontiers, est pour ce qu’ils

naissent serfs et sont nourris tels. De celle-ci en vient une autre, qu’aisément les gens

deviennent, sous les tyrans, lâches et efféminés” (ibid., 77–78, https://fr.wikisource.

org/wiki/Page:La_Boétie_-_Discours_de_la_servitude_volontaire.djvu/83).

11 “il n’a jamais été que les tyrans, pour s’assurer, ne se soient efforcés d’accoutumer

le peuple envers eux, non seulement à obéissance et servitude, mais encore à

dévotion” (ibid., 89, https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:La_Boétie_-_Discours_de_

la_servitude_volontaire.djvu/95).

12 Renoncer à sa liberté, c’est renoncer à sa qualité d’homme, aux droits de l’humanité, même

à ses devoirs. […] Une telle renonciation est incompatible avec la nature de l’homme, et c’est

ôter toute moralité à ses actions que d’ôter toute liberté à sa volonté. Enfin c’est une convention

vaine et contradictoire de stipuler d’une part une autorité absolue et de l’autre une obéissance

sans bornes.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Contrat Social. In The Political Writings of Jean-Jacques Rosseau,

Vol. 2, ed. by C. E. Vaughan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915), 28,

https://books.google.com/books?id=IqhBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA28

7

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

strength than this, to teach us how to serve”.

13

Some seventy years later, the

English revolutionary John Milton makes a similar argument, describing

“custom” as part of the double tyranny that keeps mankind in subjection:

If men within themselves would be govern’d by reason and not generally

give up their understanding to a double tyrannie, of custome from

without and blind affections within, they would discerne better what it

is to favour and uphold the Tyrant of a Nation.

14

Milton, in pamphlets that ridicule the pro-monarchical propaganda

of his day, berates what he calls “the easy literature of custom and

opinion”,

15

the authoritative-sounding, but empty writing and speaking

that teaches “the most Disciples” and is “silently receiv’d for the best

instructer”, despite the fact that it offers nothing but a “swoln visage of

counterfeit knowledge and literature”.

16

David Hume later notes “the

easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit

submission with which men resign their own sentiments and passions

to those of their rulers”. Hume explains this submission as a function

of “opinion”, or the “sense” that is inculcated into the many “of the

general advantage” to be had by obeying “the particular government

which is established”.

17

By the twentieth century, Martin Heidegger condemns “tradition”

as a manipulative force that obscures both its agenda and its origins:

The tradition that becomes dominant hereby makes what it “transmits”

so inaccessible that at first, and for the most part, it obscures it instead.

It hands over to the self-evident and obvious what has come down to us,

and blocks access to the original “sources”, from which the traditional

13 “Mais certes la coutume, qui a en toutes choses grand pouvoir sur nous, n’a en

aucun endroit si grande vertu qu’en ceci, de nous enseigner à servir” (La Boétie,

68, https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:La_Boétie_-_Discours_de_la_servitude_

volontaire.djvu/74).

14 John Milton. The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (London, 1649), 1, Sig. A2r, http://

quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A50955.0001.001/1:2?rgn=div1;view=fulltext;q1=Te

nure+of+Kings+and+Magistrates and https://books.google.com/books?id=EIg-

AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1 (1650 edition).

15 John Milton. Eikonoklastes (London, 1650), 3, Sig. A3r, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/

eebo/A50898.0001.001/1:2?rgn= div1;view=fulltext;rgn1=author;q1=Milton%2C+John

16 John Milton. The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. London, 1644, Sig. A2r, https://

books.google.com/books?id=6oI-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PP9

17 David Hume. “Of the First Principles of Government”. In Essays, Literary, Moral,

and Political (London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1870), 23, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/

pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t1fj2db8p;view=1up;seq=27

8 Love and its Critics

categories and concepts in part were actually drawn. The tradition even

makes us forget there ever was such an origin.

18

In contrast, Edward Bernays—a member of the Creel Committee which

influenced American public opinion in favor of entering WWI—regards

such manipulation as necessary to ensure the obedience of the masses:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and

opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.

Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an

invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.

We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas

suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.

19

Though Bernays thinks of such techniques as a good thing

(foreshadowing developments elsewhere in the twentieth century),

20

for

earlier thinkers like La Boétie, Milton, and Hume, it is crucial to keep a

watchful eye on those who draw “the most Disciples” after them, for

18 “Die hierbei zur Herrschaft kommende Tradition macht zunächst und zumeist

das, was sie ‘übergibt’, so wenig zugänglich, daß sie es vielmehr verdeckt. Sie

überantwortet das Überkommene der Selbstverständlichkeit und verlegt den

Zugang zu den ursprünglichen ‘Quellen’, daraus die überlieferten Kategorien und

Begriffe z. T. in echter Weise geschöpft wurden. Die Tradition macht sogar eine

solche Herkunft überhaupt vergessen” (Sein und Zeit [Tübingen: Max Niemeyer,

1967], 21).

19 Edward Bernays. Propaganda (New York: Horace Liveright, 1928), 9, https://archive.

org/details/EdwardL.BernaysPropaganda#page/n3

20 It was, of course, the astounding success of propaganda during the war that

opened the eyes of the intelligent few in all departments of life to the possibilities

of regimenting the public mind. […] If we understand the mechanism and motives

of the group mind, is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according

to our will without them knowing it? (Bernays, 27, 47). Bernays’ ideas are not far

removed from those being promulgated on the other side of the Atlantic ocean by

an aspiring literary critic and author whose Ph.D. in literature was obtained at the

University of Heidelberg in 1921, and whose critical acumen was given a real-world

application approximately a decade later:

Propaganda is not an end in itself, but a means to an end. […] Whether or not it conforms

adequately to aesthetic demands is meaningless. […] The end of our movement was to mobilize

the people, to organize the people, and win them for the idea of national revolution.

Denn Propaganda ist nicht Selbstzweck, sondern Mittel zum Zweck. […] ob es in jedem Falle

nun scharfen ästhetischen Forderungen entspricht oder nicht, ist dabei gleichgültig. […] Der

Zweck unserer Bewegung war, Menschen zu mobilisieren, Menschen zu organisieren und für

die nationalrevolutionäre Idee zu gewinnen. [March 15, 1933].

In Joseph Goebbels, Revolution der Deutschen: 14 Jahre Nationalsozialismus

(Oldenburg: Gerhard Stalling, 1933), 139.

9

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

what they are teaching may well be the lessons of obedience to what

Aleksandr Pushkin calls “Custom, despot between the people”.

21

Alongside the long narrative of demands for obedience, stands a

counter-narrative and counter-instruction in our poetry, framed in

terms of forbidden love and desire. Love challenges obedience; it is one

of the precious few forces with sufficient power to enable its adherents

to transcend themselves, their fears, and their isolation to such a degree

that it is possible to refuse the demands of power. Love does not always

succeed. But for its more radical devotees—the Dido of Ovid’s Heroides,

the troubadour poets of the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Occitania,

the famous lovers of Shakespeare, and Milton’s Adam and Eve—love is

revolutionary, an attempt to tear down the world and build it anew, not

in the image of authority, but that of a love that is freely chosen, freely

given, and freely received. Love rejects the claims of law, property,

and custom. It opposes the claims of determinism—whether theological

(Augustine, Luther, and Calvin, and the notions of original sin and

predestination), philosophical (Foucault, and the idea that impersonal

systems of power create “free subjects” in their image), or biological (as in

Baron d’Holbach’s 1770 work Système de la Nature, which maintains that

all human thought and action results from material causes and effects).

These points of view can be found all too frequently, often dressed

in the robes of what John Milton calls “pretended learning, mistaken

among credulous men […] filling each estate of life and profession, with

abject and servil[e] principles”.

22

But in the more radical examples of our

poetry, love defies servile principles, and is unimpressed by pretended

learning. Neither is love merely a Romantic construct, a product of “the

long nineteenth century [that extends] well into the twenty-first”,

23

nor

a secular replacement for religious traditions. As Simon May points out,

“[b]y imputing to human love features properly reserved for divine

love, such as the unconditional and the eternal, we falsify the nature

of this most conditional and time-bound and earthly emotion, and

21 “Обычай деспот меж людей”. Evgeny Onegin, 1.25.4. In Aleksandr Sergeevich

Pushkin. Sobraniye Sochinenii. 10 Vols., ed. by D. D. Blagoi, S. M. Bondi, V. V.

Vinogradov and Yu. G. Oksman (Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1959),

Vol. 4, 20, http://rvb.ru/pushkin/01text/04onegin/01onegin/0836.htm

22 John Milton. The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. London, 1644, Sig. A2r, https://

books.google.com/books?id=6oI-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PP9

23 Simon May. Love: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), xii.

10 Love and its Critics

force it to labor under intolerable expectations”.

24

It is precisely “time-

bound and earthly” love—a passion that always brings an awareness

of time running out, and the concomitant urge to fight to extend that

time even by the merest moments—that is the powerful counterweight

to the “servil[e] principles” imposed on us by the individuals and

institutions that demand our obedience. Too often, the poetry written

about this love has been ill-served by its ancient and modern critics.

Reading the theological and academic critics of poetry inspires the

troubling realization that many such critics are part of the very system

of authority and obedience which, La Boétie argues, accustoms people

to tyrants, and against which the poetry itself protests.

25

III

Love’s Critics: The Hermeneutics of Suspicion and the

Authoritarian Approach to Criticism

How does this alignment between literary criticism and repressive

authority function? By denying poetry—particularly love poetry—

the ability to serve as a challenge to the structures of authority in

the societies in which it is written.

26

As we will see especially clearly

24 Ibid., 4–5.

25 Obedience is the soil in which universities first took root. In their beginnings,

universities were training grounds for service in the church or at court (for those

students who took degrees), and institutions that inculcated obedience in the wider

population. The subversiveness of an Abelard or a Wycliffe—which in each case

came at a far greater cost than any paid, or even contemplated by the academic

critic today—is most clearly understood in that context. This is best illustrated

by the Authentica Habita, the 1158 decree of the German Emperor Frederick I

(Barbarossa) granting special privileges to teachers and students of the still-forming

University of Bologna in order that “students, and divine teachers of the sacred

law, […] may come and live in security” (“scholaribus, et maxime divinarum atque

sacrarum legum professoribus, […] veniant, et in eis secure habitient”). This decree

also outlined what Frederick believed to be the essential purpose of education:

“knowledge of the world is to illuminate and inform the lives of our subjects, to

obey God, and ourself, his minister” (“scientia mundus illuminatur ad obediendum

deo et nobis, eius ministris, vita subjectorum informatur”) (Paul Krueger, Theodor

Mommsen, Rudolf Schoell, and Whilhelm Kroll, eds. Corpus Iuris Civilis, Vol. 2

[Berlin: Apud Weidmannos, 1892], 511, https://books.google.com/books?id=2hvTA

AAAMAAJ&pg=PA511).

26 In the “human sciences”, critics often “act as agents of the micro-physics of power”

(Elisabeth Strowick. “Comparative Epistemology of Suspicion: Psychoanalysis,

Literature, and the Human Sciences”. Science in Context, 18.4 [2005], 654, https://doi.

11

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

when we consider the commentary that surrounds the poetry of John

Milton, the thinking behind such work often displays “a high degree

of submission to the authorities who are perceived to be established”,

27

whether that authority is political, cultural, or intellectual. There is an

endless body of criticism that serves not only to undermine poetry’s

potential for political, theological, and even aesthetic resistance, but

to restrict the manner in which readers encounter and understand

poetry. From the beginning, together with the tradition of love poetry,

a tradition of criticism (expressed now from both “conservative” and

“radical” points of view)

28

has grown that subordinates and dismisses

human passion and desire, often arguing that what merely seems to

be passionate love poetry is actually properly understood as something

else (worship of God, subordination to Empire, entanglement within

the structures of language itself). The pattern of such criticism—from

the earliest readings of the Song of Songs to contemporary articles

written about a carpe diem poem like Robert Herrick’s “To the Virgins

to Make Much of Time”—is to argue that the surface of a poem hides

a “real” or “deeper” meaning that undermines the apparent one, and

that the critic’s job is to tear away the misleading surface in order to

expose the “truth” that lies beneath it. Frederic Jameson exemplifies

this technique in his argument that the true function of the critic is to

analyze texts and culture through “a vast interpretive allegory in which

a sequence of historical events or texts and artifacts is rewritten in terms

of some deeper, underlying, and more ‘fundamental’ narrative”.

29

Louis Althusser describes interpretation similarly, as “detecting the

undetected in the very same text it reads, and relating it to another

org/10.1017/S0269889705000700). Noam Chomsky, when asked how “intellectuals

[…] get away with their complicity [with] powerful interests”, gives a telling

response: “They are not getting away with anything. They are, in fact, performing

a service that is expected of them by the institutions for which they work, and they

willingly, perhaps unconsciously, fulfill the requirements of the doctrinal system”

(“Beyond a Domesticating Education: A Dialogue”. In Noam Chomsky, Chomsky on

Miseducation [Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004], 17).

27 Bob Altermeyer. The Authoritarian Specter (Cambridge: Havard University Press,

1996), 6.

28 Along with the “right-wing” authoritarianism cited above, Altermeyer also defines

a “left-wing” authoritarianism which displays “a high degree of submission to

authorities who are dedicated to overthrowing the established authorities” (219).

29 Frederic Jameson. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 13.

12 Love and its Critics

text, present as a necessary absence in the first”.

30

We can trace similar

thinking all the way back to the controversies over Homer and Hesiod

in the sixth century BCE:

31

The Homeric representations of the gods roused a protest on the part of

the founder of the Eleatics, Xenophanes of Colophon (fl. 540–500 B.C),

who says that “Homer and Hesiod have imputed to the gods all that is

blame and shame for men”. […] In reply to protests such as these, some

of the defenders of Homer maintained that the superficial meaning of

his myths was not the true one, and that there was a deeper sense lying

below the surface. This deeper sense was, in the Athenian age, called the

ὑπόνοια[hyponoia–suspicion],andtheὑπόνοιαofthisageassumedthe

name of “allegories” in the times of Plutarch. […] Anaxagoras […] found

in the web of Penelope an emblem of the rules of dialectic, the warp being

the premises, the woof the conclusion, and the flame of the torches, by

which she executed her task, being none other than the light of reason.

[…] But no apologetic interpretation of the Homeric mythology was of

any avail to save Homer from being expelled with all the other poets

from Plato’s ideal Republic.

32

Such readings originally tried to defend poetry against its critics,

33

though in a rather different sense than did Eratosthenes, the third-

century BCE librarian of Alexandria, who held that “poets… in all

30 “décèle l’indécelé dans le texte même qu’elle lit, et le rapporte à un autre texte,

présent d’une absence nécessaire dans le premier” (Louis Althusser. Lire le Capital

[Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996], 23).

31 BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era) are used here throughout

(except in quotations, where usage may differ) in lieu of the theologically-inflected

BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domini).

32 Sir John Edwin Sandys. A History of Classical Scholarship, Vol. I: From the Sixth

Century B.C. to the End of the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1903), 29–31, https://archive.org/stream/historyofclassic00sanduoft#page/29

33 Francois Rabelais, who finds a good reason to laugh at nearly everything, laughs

also at this particular absurdity of literary history:

Do you believe, in faith, that Homer, when he was writing the Iliad and Odyssey, thought of the

allegories that Plutarch, Heraclides Ponticq, Eustalius, and Cornutus dressed him in, and which

Politian took from them? If you believe that, you don’t approach by foot or by hand anywhere

near my opinion.

Croyez vous en vostre foy qu’oncques Homere, escripvant Iliade et Odyssée, pensast es

allegories lesquelles de lui ont calefreté Plutarque, Heraclides Ponticq, Eustatie, Phornute, et

ce d’yceulx Politian ha desrobé? Si li croyez, vous n’aprochez ne de piedz, ne de mains a mon

opinion.) (Francois Rabelais. “Prolog”. Gargantua et Pantagruel. In Œuvres de Rabelais, Vol. 1 [Paris:

Dalibon, 1823], 24–25, https://books.google.com/books?id=a6MGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA24)

13

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

things aim to persuade and delight, not instruct”,

34

or Philip Sidney,

for whom “the Poet, he nothing affirmeth, and therefore never lieth”.

35

But suspicion has long since been adopted by the critics as a method of

attack, rather more in the spirit of Plato than in the spirit of Sidney or

those early defenders of Homer and Hesiod.

Employing a method Paul Ricoeur calls the hermeneutics of

suspicion (les herméneutiques du soupçon), the modern version of this

reading strategy is a matter of cunning (falsification) encountering

a greater cunning (suspicion), as the “false” appearances of a text are

systematically exposed by the critic:

Three masters, who appear exclusive from each other, are dominant:

Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud. […] The fundamental category of

consciousness, for the three of them, is the relation between hidden-

shown or, if one prefers, simulated-manifest. […] What they have all

three tried, by different routes, is to align their “conscious” methods of

decryption with the “unconscious” work of encryption they attributed to

the will to power, to social being, to the unconscious psyche. […] What

then distinguishes Marx, Freud and Nietzsche is the general hypothesis

concerning both the process of “false” consciousness and the decryption

method. The two go together, since the suspicious man reverses the

falsifying work of the deceitful man.

36

For Ricoeur, the hermeneutics of suspicion is not something that is

simply borrowed from the “three masters”; rather, it is modern literature

itself that teaches a reader to read suspiciously:

34 “Ποιητὴν […] πάντα στοχάζεσθαι ψυχαγωγίας, οὐ διδασκαλίας”. Strabo,

Geography, 1.2.3. In Strabo, Geography, Vol. I: Books 1–2, ed. by Horace Leonard Jones.

Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1917, 54.

35 Philip Sidney. The Defence of Poesie. In The Complete Works of Sir Philip Sidney, Vol. III,

ed. by Albert Feuillerat (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923), 29, https://

archive.org/stream/completeworks03sidnuoft#page/29

36 Troi maîtres en apperance exclusifs l’un de l’autre la dominent, Marx, Nietzsche et Freud. […]

La catégorie fondamentale de la conscience, pour eux trois, c’est le rapport caché-montré ou, si

l’on préfére, simulé-manifesté. […] Ce qu’ils ont tenté tous trois, sur des voies différentes, ce’st

de faire coïncider leurs methods “conscientes” de déchiffrage avec le travail “inconscient” du

chiffrage qu’ils attribuaient à la volonté de puissance, à l’être social, au psychisme inconscient.

[…] Ce qui distingue alors Marx, Freud et Nietzsche, c’est l’hypothèse gènèrale concernant à la

fois le processus de la conscience “fausse” et la méthode de déchiffrage. Les deux vont de pair,

puisque l’homme du soupçon fait en sens inverse le travail de falsification de l’homme de la ruse.

Paul Ricoeur. De l’interprétation. Essai sur Freud (Paris: Seuil, 1965), 32, 33–34.

14 Love and its Critics

It may be the function of more corrosive literature to contribute to making

a new type of reader appear, a suspicious reader, because the reading

ceases to be a confident journey made in the company of a trustworthy

narrator, but reading becomes a fight with the author involved, a struggle

that brings the reader back to himself.

37

Yet suspicion is more fundamental, more deeply rooted than can be

explained by the lessons of reading. Not long after outlining his analysis

of the “three masters”, Ricoeur makes an even starker and more

dramatic statement: “A new problem has emerged: that of the lie of

consciousness, and of consciousness as a lie”.

38

Here, if one desires it, is

a warrant to regard all apparent meaning (indeed, all appearance of any

kind) as a lie in need of being dismantled and exposed. Such ideas, and

the reading strategies they have inspired, have done yeoman’s work in

literary and historical scholarship over the last several decades. But as

with so many useful tools, this one can be, and has been overused.

39

Rita

Felski pointedly questions why this approach has become “the default

option” for many critics today:

Why is it that critics are so quick off the mark to interrogate, unmask,

expose, subvert, unravel, demystify, destabilize, take issue, and take

umbrage? What sustains their assurance that a text is withholding

something of vital importance, that their task is to ferret out what lies

concealed in its recesses and margins?

40

37 Ce peut être la fonction de la littérature la plus corrosive de contribuer à faire apparaître un

lecteur d’un nouveau genre, un lecteur lui-même soupçonneux, parce que la lecture cesse

d’être un voyage confiant fait en compagnie d’un narrateur digne de confiance, mais devient

un combat avec l’auteur impliqué, un combat qui le reconduit à lui-même.

Paul Ricoeur. Temps et Récit, Vol. 3: Le Temps Raconté (Paris: Seuil, 1985), 238.

38 “Une problème nouveau est né: celui du mensonge de la conscience, de la

conscience comme mensonge” (Paul Ricoeur. Le Conflit des Interprétations: Essais

D’Herméneutique [Paris: Seuil, 1969], 101).

39 These readings demonstrate

the thought pattern that’s at the basis of literary studies, and of any self-enclosed hermetically

sealed sub-world that seeks to assert theoretical hegemony over the rest of the world. […]

The individual is not the measure of all things: I, the commentator, am the measure of all

things. You always have to wait for me, the academic or theoretician, to explain it to you. For

example, you’re really doing A or B because you’re a member of a certain class and accept its

presuppositions. Or you’re really doing C and D because of now-inaccessible events in your

childhood. What you personally think about this doesn’t matter.

Bruce Fleming. What Literary Studies Could Be, And What It Is (Lanham: University

Press of America, 2008), 100.

40 Rita Felski. The Limits of Critique (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 5.

15

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

Maintaining that “suspicious reading has settled into a mandatory method

rather than one approach among others”, Felski describes this method

as “[i]ncreasingly prescriptive as well as excruciatingly predictable”,

portraying its influence as one that “can be stultifying, pushing thought

down predetermined paths and closing our minds to the play of detail,

nuance, quirkiness, contradiction, happenstance”. Literary criticism

that leans heavily on this method can lend itself to an authoritarian

approach to reading, as “the critic conjures up ever more paralyzing

scenarios of coercion and control”,

41

while readers “have to appeal to

the priestly class that alone can explain”

42

the text. Such criticism treats

texts as “imaginary opponents to be bested”

43

in service of an accusatory,

prosecutorial agenda, as “[s]omething, somewhere—a text, an author, a

reader, a genre, a discourse, a discipline—is always already guilty of

some crime”.

44

The trials have become so zealous and overwhelmingly

numerous that they have long since become formulaic,

45

products of

a template-driven approach whose verdicts can be anticipated at the

beginning of the essays and books that use this method.

But why? What is the appeal of this approach? Karl Popper suggests

that it is because “[t]hese theories appear to be able to explain practically

everything”, while a devotion to this method has the effect “of an

intellectual conversion or revelation, opening your eyes to a new truth

hidden from those not yet initiated”. Those who undergo this conversion

behave in much the same way as new cult members, on the lookout for

heresy,

46

dividing the world into believers and unbelievers: “Once your

41 Ibid., 34.

42 Fleming, 100.

43 Felski, The Limits of Critique, 111.

44 Ibid., 39.

45 As Felski notes:

Anyone who attends academic talks has learned to expect the inevitable question: “But what

about power?” Perhaps it is time to start asking different questions: “But what about love?”

Or: “Where is your theory of attachment?” To ask such questions is not to abandon politics

for aesthetics. It is, rather, to contend that both art and politics are also a matter of connecting,

composing, creating, coproducing, inventing, imagining, making possible: that neither is

reducible to the piercing but one-eyed gaze of critique.

The Limits of Critique, 17–18.

46 Felski traces this attitude back to “the medieval heresy trial”, noting that “[h]eresy

presented a hermeneutic problem of the first order and the transcripts of religious

inquisitions reveal an acute awareness on the part of inquisitors that truth is not

self-evident, that language conceals, distorts, and contains traps for the unwary,

16 Love and its Critics

eyes [are] thus opened you [see] confirmed instances everywhere: the

world [is] full of verifications of the theory […] and unbelievers [are]

clearly people who [do] not want to see the manifest truth; who refuse

to see it”.

47

In addition to the influence of Ricoeur’s “three masters”, this

approach also hinges on on a widely-diffused (mis)use of the work

of Martin Heidegger, especially his engagement with the meaning

of “truth” or Wahrheit. For Heidegger, “the essence of truth is always

understood in terms of unconcealment”,

48

a notion he derives from

the Greek term ἀλήθεια (aletheia—discovered or uncovered truth) in

the pre-Socratic philosophers Parmenides and Heraclitus. Heidegger

divides the concept of truth into correctness (Richtigkeit) or accurate

correspondence of ideas with things as they presently are in the world, and

the unconcealedness or discoveredness (Unverborgenheit or Entdecktheit)

of entities. The first is necessarily grounded in, and dependent upon the

second, for there can be no truth about things in the world without things

in the world. For Heidegger, truth as correctness “has its basis in the truth

as unconcealedness”,

49

while “the unconcealment of Being as such is the

basis for the possibility of correctness”.

50

Thus Wahrheit is both the surface

truth of what exists and the deeper truth that existence itself exists.

But what has any of this to do with the reading of literature?

Heidegger’s thought proposes a two-level structure, much like that

found in Parmenides, who argued that τὸ ἐὸν—to eon, or What Is—

should be understood in terms of an unchanging reality behind the

changing appearances of the world.

51

It is also seen in the paradoxes

that words should be treated cautiously and with suspicion” (“Suspicious Minds”.

Poetics Today, 32: 2 [Summer 2011], 219, https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-1261208).

47 Karl Popper. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (New

York: Basic Books, 1963), 34.

48 Mark A. Wrathall. Heidegger and Unconcealment: Truth, Language, and History

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 12.

49 “hat ihren Grund in der Wahrheit als Unverborgenheit” (Martin Heidegger.

Grundfragen der Philosophie. Ausgewählte “Probleme” der “Logik”. Gesamtausgabe.

II. Abteilung: Vorlesungen 1923–1944. Band 45 [Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio

Klostermann Verlag, 1984], 97–98).

50 “Die Unverborgenheit des Seienden als solchen ist der Grund der Möglichkeit der

Richtigkeit” (ibid., 102).

51 In the extant fragments, Parmenides describes τὸ ἐὸν as the kind of eternal,

unchanging whole that later Christian theologians will use as a basis for their

understandings of the divine:

17

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

of Zeno (designed, as in the example of Achilles and the Tortoise, to

demonstrate the unreality of the world of motion and appearances

52

),

and the dialogues of Plato (for whom the eidos or Idea is the ultimate

reality that the world of appearances merely exemplifies or participates

in—μέθεξις / methexis—in an incomplete and shadowy way

53

).

Heidegger argues that to get at truth not merely in its surface, concrete,

or ontic sense, but in its deeper, structural, ontological sense, the seeker

must go through a process of unveiling, reaching a state he called

disclosedness (Erschslossenheit), accompanied by a process of clearing

(Lichtung), removing what is inessential and shining a light (Licht) on

the core that remains.

The basic working method of much literary criticism in its modern

European and American forms is indebted to Heidegger’s recovery and

ἔστινἄναρχονἄπαυστον

[…]

Ταὐτόντ’ἐνταὐτῷτεμένονκαθ’ἑαυτότεκεῖται

χοὔτωςἔμπεδοναὖθιμένει·κρατερὴγὰρἈνάγκη

πείρατοςἐνδεσμοῖσινἔχει,τόμινἀμφὶςἐέργει,

οὕνεκενοὐκἀτελεύτητοντὸἐὸνθέμιςεἶναι·.

It exists without beginning or ending

[…]

Identical in its sameness, it remains itself and standing

Thus firmly-set there, for strong and mighty necessity

Limits it, holds it in chains, and shuts it in on both sides.

Because of this, it is right what is should not be incomplete.

Fragment 8, ll. 26, 29–32, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, ed. by Hermann Diels

(Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1903), 124, https://archive.org/stream/

diefragmenteder00krangoog#page/n140

52 According to Aristotle’s summary,

The second of these is called “Achilles”. It is this in which the slowest runner is never overtaken

by the fastest; because since the swifter runner in the chase is always, at any given moment,

first forced to reach the point where the fleeing runner set into motion, of necessity the slowest

runner, who had the headstart, will always be in the lead.

Δεύτερος δ΄ ὁ καλούμενος Ἀχιλλεύς. ἔστι δ΄ οὗτος ὅτι τὸ βραδύτατον οὐδέποτε

καταληφθήσεται θέον ὑπὸ τοῦ ταχίστου· ἔμπροσθεν γὰρ ἀναγκαῖον ἐλθεῖν τὸ διῶκον,

ὅθενὥρμησετὸφεῦγον,ὥστ΄ἀείτιπροέχεινἀναγκαῖοντὸβραδύτερον.

Aristotle, Physics, Vol. II, Books 5–8, ed. by P. H. Wicksteed and F. M. Cornford (Loeb

Classical Library, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934), 180, 182. This

paradox is helpfully visualized in the following Open University video: https://

www.youtube.com/watch?v=skM37PcZmWE

53 The Instance (or the Particular) shares in the nature of the Eidos (or form / idea),

though imperfectly: “The term Methexis, Participation […] connote[s] a closer

relation of the Instance to the Eidos […]: the Instance really has something of the

Eidos in it, if not the Eidos in its full purity” (John Niemeyer Findlay. Plato: The

Written and Unwritten Doctrines [New York: Routledge, 1974], 37).

18 Love and its Critics

reformulation of this pre-Socratic notion of truth as disguised, hidden

away, and obscured by a layer of what one might call “lesser truth”

or illusion. Heidegger’s influence on French thinkers like Ricoeur and

Jacques Derrida is profound,

54

and its traces work their way through

American criticism like that of “Deconstructionists” such as Paul de

Man,

55

and even the “New Historicist” work of Stephen Greenblatt

(through Foucault

56

) and the innumerable scholars and critics who

have followed in his wake in recent decades. Much of the criticism we

encounter in this book operates on the assumption that a poem has a

surface (the actual words and relationships between them) that must be

cleared away in order to reveal the truth. The complexity of Heidegger’s

thought is often left behind by such a process,

57

but what remains is the

54 Walter A. Brogan refers to Derrida’s concept of différance as “a radical and liberated

affirmation of Heidegger’s thought” (“The Original Difference”. Derrida and

Différance, ed. by David Wood and Robert Bernasconi [Evanston: Northwestern

University Press, 1985], 32). As Andre Gingrich notes, “Heidegger’s own

phenomenological appreciation of literature influenced Ricouer’s hermeneutic

approach”, and “[b]oth Ricouer and Derrida acknowledged Heidegger’s strong

influence upon major areas of their respective works” (“Conceptualising Identities:

Anthropological Alternatives to Essentialising Difference and Moralizing

about Othering”. In Gerd Baumann and Andre Gingrich, eds. Grammars of

Identity / Alterity: A Structural Approach [New York: Berghahn Books, 2004], 6–7).

For a comprehensive account of Heidegger’s influence on French intellectuals of

the mid-twentieth century, see Dominique Janicaud’s Heidegger in France, Indiana

University Press, 2015.

55 “De Man’s relation to Heidegger is especially contorted. De Man from the start

contests Heidegger’s signature notion of Being, but does so in an authentically

deconstructive fashion, such that de Man’s own counter-notion of ‘language’

cannot be grasped apart from an appreciation of Heidegger’s project” (Joshua

Kates. “Literary Criticism”. In The Routledge Companion to Phenomenology, ed. by

Sebastian Luft [New York: Routledge, 2012], 650–51).

56 In Foucault’s account, “Heidegger has always, for me, been the essential

philosopher” (“Heidegger a toujours été pour moi le philosophe essential”). In his

“Le retour de la morale”. In his Dits et écrits, 1954–1988. Vol. IV: 1980–1988 (Paris:

Gallimard, 1994), 696–707 (703).

57 For Heidegger, art itself (and not its interpretation or interpreters) is that which

reveals (or unconceals) the truth of Being: “The artwork opens the Being of

beings in its own way. In the work this opening, this unconcealing, of the truth

of beings happens. In art, the truth of beings has set itself in motion. Art is the

truth setting itself-into-works” (“Das Kunstwerk eröffnet auf seine Weise das Sein

des Seienden. Im Werk geschieht diese Eröffnung, d.h. das Entbergen, d.h. die

Wahrheit des Seiended. Im Kunstwerk hat sich die Wahrheit des Seienden ins Werk

gesetzt. Die Kunst ist das Sich-ins-Werk-Setzen der Wahrheit”) (“Der Ursprung

des Kunstwerkes”. Holzwege: Gesamtusgabe, Vol. V [Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio

Klostermann, 1977], 25).

19

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

basic notion that the truth of a poem is concealed by its words, and by

its writer, and that the job of the critic is to pull back the curtains.

Some critics argue, however, that “truth” is a naïve concept,

especially where the interpretation of poetry is concerned.

58

These

critics argue that “to impute a hidden core of meaning [is] to subscribe

to a metaphysics of presence, a retrograde desire for origins, a belief in

an ultimate or foundational reality”.

59

Richard Rorty addresses the split

between the two camps that Felski calls “Digging Down” and “Standing

Back”

60

by first emphasizing their similarity, arguing that “they both

start from the pragmatist refusal to think of truth as correspondance to

reality”,

61

before outlining the crucial difference:

The first kind of critic […] thinks that there really is a secret code and

that once it’s discovered we shall have gotten the text right. He believes

that criticism is discovery rather than creation. [The other kind of critic]

doesn’t care about the distinction between discovery and creation […]

58 For Roland Barthes, the critical search for “truth” is quite useless, as there is no

“truth”, nor even any operant factor in a text, except language itself:

Once the author is removed, the claim to “decipher” a text becomes quite useless. To give an

Author to a text is to impose a knife’s limit on the text, to provide it a final signification, to close

the writing. This design is well suited to criticism, which then wants to give itself the important

task of discovering the Author (or his hypostases: society, history, the psyche, liberty) beneath

the work: the Author found, the text is “explained”, the critic has conquered; so there is nothing

surprising that, historically, the reign of the Author has also been that of the Critic, but also that

criticism (even if it be new) should on this day be shaken off at the same time as the Author.

L’Auteur une fois éloigné, la prétention de “déchiffrer” un texte devient tout à fait inutile.

Donner un Auteur à un texte, c’est imposer à ce texte un cran d’arrêt, c’est le pourvoir d’un

signifié dernier, c’est fermer l’écriture. Cette conception convient très bien à la critique, qui veut

alors se donner pour tâche importante de découvrir l’Auteur (ou ses hypostases: la société,

l’histoire, la psyché, la liberté) sous l’œuvre: l’Auteur trouvé, le texte est “expliqué”, le critique

a vaincu; il n’y a donc rien d’étonnant à ce que, historiquement, le règne de l’Auteur ait été aussi

celui du Critique, mais aussi à ce que la critique (fût-elle nouvelle) soit aujourd’hui ébranlée en

même temps que l’Auteur.

“La mort de l’auteur”. In Le Bruissement de la Langue. Essais Critiques IV. Paris: Seuil,

1984, 65–66.

59 Felski, The Limits of Critique, 69.

60 “The first pivots on a division between manifest and latent, overt and covert, what

is revealed and what is concealed. Reading is imagined as an act of digging down

to arrive at a repressed or otherwise obscured reality”, while the second works

by “distancing rather than by digging, by the corrosive force of ironic detachment

rather than intensive interpretation. The goal is now to ‘denaturalize’ the text,

to expose its social construction by expounding on the conditions in which it is

embedded” (ibid., 53, 54).

61 Richard Rorty. The Consequences of Pragmatism (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1982), 151.

20 Love and its Critics

He is in it for what he can get out of it, not for the satisfaction of getting

something right.

62

Though Rorty might be accused of cynicism here, there is an identifiable

split between the kinds of critics who apply a hermeneutics of suspicion

in what might be called a “Freudian” sense—digging down through

the layers and strata of a culture or text as a psychoanalyst would dig

through the manifest content of a patient’s dreams in search of a deeper,

but hidden, content (or truth)—and those who apply a hermeneutics

of suspicion in what might be called a “Nietzschean” sense, stripping

away the pretenses and postures of a culture or text in order to

demonstrate that it is pretenses and postures all the way down (that

there is no truth but the provisional one we create, dismantle, modify,

destroy, etc.).

63

But as Felski points out, “[in] spite of the theoretical and

political disagreements between styles of criticism, there is a striking

resemblance at the level of ethos—one that is nicely captured by François

Cusset in his phrase ‘suspicion without limits’”.

64

Each kind of criticism

is in the business of near-perpetual unveiling. Where they differ is that

one school seeks to reveal what they believe lies behind the veils, while

the other school seeks to reveal the “fact” that there are only veils with

nothing behind them.

65

62 Ibid., 152.

63 Such a “Nietzschean” reading can be seen in J. Hillis Miller’s deconstructive reading

of Percy Shelley’s “The Triumph of Life”, in which Miller claims that Shelley’s

poem, “like all texts, is ‘unreadable’, if by ‘readable’ one means open to a single,

definitive, univocal interpretation” (J. Hillis Miller. “The Critic as Host”. Critical

Inquiry, 3: 3 [Spring, 1977], 447).

64 Felski, The Limits of Critique, 20.

65 New Historicism falls into the first camp. It is perpetually in a state of high alert

for the operations of power, and constantly on the lookout for “complicity with

structures of power in whose language [knowledge] would have no choice but

to speak” (Vincent P. Pecora. “The Limits of Local Knowledge”. In Harold Aram

Veeser, ed. The New Historicism [New York: Routledge, 1989], 267). As Foucault—

in many ways, the “godfather” of New Historicism—puts it: “there is no power

relationship without a correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any field

of knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute power relations at the same

time” (“qu’il n’y a pas de relation de pouvoir sans constitution corrélative d’un

champ de savoir, ni de savoir qui ne suppose et ne constitue en même temps des

relations de pouvoir”) (Surveiller et Punir: Naissance de la Prison [Paris: Gallimard,

1975], 32). The New Historicist critic looks to unveil or reveal the operations (and

cooperations) of power and knowledge, all the while risking being complicit

with the very structures of power he or she seeks to unmask, since “every act of

unmasking, critique, and opposition uses the tools it condemns and risks falling

21

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

Such skeptical criticism, whose two branches are more alike than

different, “thinks of itself as battling orthodoxy yet it is now the reigning

orthodoxy, no longer oppositional but obligatory”.

66

This “obligatory”

stance is frequently taken up in service of what its practitioners

claim is an adversarial agenda, a way of reading texts that resists the

ideologies and practices of power by revealing or unveiling them. It

is in such criticism that we encounter terms like interrogation, with all

of its none-too-subliminal suggestions of violence; a fire-against-fire

use of violent analysis to uncover or reveal (or fabricate) a “violence”

inherent in the text. As Kate McGowan puts it, “[t]he value of unrelenting

interrogation is the value of resistance”.

67

But it is often “far from evident”

how interrogations of poems, plays, and novels “published in […]

undersubscribed academic journal[s]”

68

serve as effective resistance to

anything except poetry itself. Such criticism and its “close ties to modes

of professionalization and scholarly gatekeeping make it hard to sustain

the claim that there is something intrinsically radical or resistant”

69

prey to the practice it exposes” (Harold Aram Veeser. “Introduction”. In his, ed. The

New Historicism, xi). Deconstruction belongs to the second camp. For Paul de Man,

literature obsessively points to “a nothingness”, while “[p]oetic language names

this void […] and never tires of naming it again”. For de Man, “[t]his persistant

naming is what we call literature” (Blindness and Insight, Essays in the Rhetoric of

Contemporary Criticism [New York: Oxford University Press, 1971], 18). For J.

Hillis Miller, an author’s works “are at once open to interpretation and ultimately

indecipherable, unreadable. His texts lead the critic deeper and deeper into a

labyrinth until he confronts a final aporia”. The critic burrows further and further

beneath the veil of surface appearances only to find unresolvability, an impasse,

which leads us to understand that “personification” in literature “will always

be divided against itself, folded, manifold, dialogical rather than monological”.

The final assertion (or unveiling) of the essay is that literature is best understood

through “multiple contradictory readings in a perpetual fleeing away from any

fixed sense” (J. Hillis Miller. “Walter Pater: A Partial Portrait”. Daedalus, 105: 1, In

Praise of Books [Winter, 1976], 112).

66 Felski, The Limits of Critique, 148. Bruce Fleming expresses a similar idea: “[t]he

people in charge of contemporary classrooms see themselves as overthrowing

prejudices, fiercely challenging the status quo. In fact, for the purposes of literary

studies, they are the status quo” (27).

67 Kate McGowan. Key Issues in Critical and Cultural Theory (Buckingham: Open

University Press, 2007), 26. Emphasis added.

68 Felski, The Limits of Critique, 143.

69 Ibid., 138.

22 Love and its Critics

about either its style or its substance.

70

Suspicion becomes its own point,

perpetuating itself for itself, operating as a tribal shibboleth

71

that allows

members of an in-group to recognize one another. In Eve Sedgwick’s

view, readings that stem from this method battle with and obscure

poetry, “blotting out any sense of the possibility of alternative ways of

understanding or things to understand”.

72

As these alternative ways of

understanding are blotted out, poetry, and its readers, can be reshaped

into a desired ideological form. This reshaping presents itself in a

number of ways, but two lines of argument have long been dominant:

first, the idea that poetry, and language more generally, refers only to

itself; and second, the idea that the author is “dead” and irrelevant—

perhaps even an impediment—to the understanding of poetry.

70 In Noam Chomsky’s view, such interrogations are impediments to meaningful resistance:

In the United States, for example, it’s mostly confined to Comparative Literature departments.

If they talk to each other in incomprehensible rhetoric, nobody cares. The place where it’s been

really harmful is in the Third World, because Third World intellectuals are badly needed in the

popular movements. They can make contributions, and a lot of them are just drawn away from

this—anthropologists, sociologists, and others—they’re drawn away into these arcane, and in

my view mostly meaningless discourses, and are dissociated from popular struggles.

“Noam Chomsky on French Intellectual Culture & Post-Modernism [3/8]”. Interview

conducted at Leiden University (March 2011. Posted March 15, 2012), https://www.

youtube.com/v/2cqTE_bPh7M&feature=youtu.be&start=409& end=451 [6:49–7:31].

71 This term, from Judges 12:5–6, comes out of a context of war and violence, in which

one tribe needed a quick and easy way of identifying infiltrators from the enemy side:

And the Gileadites captured the passages of the Jordan to Ephraim, and it happened that when

the fugitive Ephraimites said “let me cross over”, the men of Gilead said to them “are you an

Ephraimite?” And if he said, “no”, then they said, “say Shibboleth”, and if he said “Sibboleth”,

because he could not pronounce it right, then they took him and slew him at the passages of the

Jordan, and there fell at that time forty two thousand Ephraimites.

Unless otherwise noted, all Hebrew Biblical text is quoted from Biblia Hebraica

Stuttgartensia, ed. by Karl Elliger and Willhelm Rudolph (Stuttgart: Deutsche

Bibelgesellschaft, 1983). All Greek Biblical text is quoted from The Greek New

Testament, ed. by Barbara Aland (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2014).

72 Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham

and London: Duke University Press, 2003), 131.

23

1. Love and Authority: Love Poetry and its Critics

IV

The Critics: Poetry Is About Poetry

This notion can be traced to Maurice Blanchot, a right-wing journalist

who became a left-wing philosopher and literary critic after the Second

World War. Blanchot argues—in a sideswipe at Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1948

work What is Literature?—that “it has been found, surprisingly, that the

question ‘What is literature?’ has never received anything other than

insignificant answers”.

73

Sartre argues that the poet writes to escape the

world, while the prose writer engages with it, “for one, art is a flight;

for the other, a means of conquest”.

74

The politically-committed prose

writer works for the cause of liberty: “the writer, a free man addressing

other free men, has only one subject: liberty”,

75

and such work only has

meaning in a free society: “the art of prose is tied to the only regime in

which prose holds any meaning: democracy”.

76