This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003.

Copyright © 2018 CNA

This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue.

It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor.

Distribution

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited.

SPECIFIC AUTHORITY: N00014-16-D-5003 4/17/2018

Request additional copies of this document through inquiries@cna.org.

Photography Credit: Toy Story meme created via imgflip Meme Generator, available at

https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, accessed March 24, 2018.

Approved by: April 2018

Dr. Jonathan Schroden, Director

Center for Stability and Development

Center for Strategic Studies

i

Abstract

The term meme was coined in 1976 by Richard Dawkins to explore the ways in which

ideas spread between people. With the introduction of the internet, the term has

evolved to refer to culturally resonant material—a funny picture, an amusing video, a

rallying hashtag—spread online, primarily via social media. This CNA self-initiated

exploratory study examines memes and the role that memetic engagement can play

in U.S. government (USG) influence campaigns. We define meme as “a culturally

resonant item easily shared or spread online,” and develop an epidemiological model

of inoculate / infect / treat to classify and analyze ways in which memes have been

effectively used in the online information environment. Further, drawing from our

discussions with subject matter experts, we make preliminary observations and

identify areas for future research on the ways that memes and memetic engagement

may be used as part of USG influence campaigns.

ii

This page intentionally left blank.

iii

Executive Summary

If you’ve spent any time online, you have probably encountered a meme. There are

thousands of memes in circulation (with new ones being created regularly) on a

variety of social media websites. The figure below represents one of the more

popular memes, a riff on a scene from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Figure.

“One Does Not Simply Walk Into Mordor” (on memes)

Source: imgflip Meme Generator, https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, accessed March

24, 2018.

While images like the one above are popularly known today as “memes,” a closer

look at the concept reveals a nuanced and complex set of ideas worthy of further

inquiry. The very concept of the term remains contested, and has evolved

considerably since first introduced in 1976, but for the purposes of this report we

define meme as a culturally resonant item easily shared or spread online.

While individual internet users have been using memes online for years, more

recently there have been suggestions that memes might also have utility for the U.S.

government (USG) as part of its information and influence campaigns to counter

state actors such as Russia and non-state actors such as the Islamic State. However,

the state of research on both memes and this type of activity—which we are referring

to as memetic engagement—remains nascent.

To help address this, CNA initiated an exploratory study of the applicability, utility,

and role of memes and memetic engagement within USG influence campaigns. The

purpose of this study is to further the conversation on memetic engagement within the

iv

USG influence community, as it considers novel approaches to countering state and

non-state actors in the online information environment.

To do this, CNA reviewed the literature on the history of memes, memetic

engagement, and so-called “memetic warfare,” along with psychology and marketing

literature that explores the role of virality and persuasion in changing people’s

attitudes and behaviors. Upon completion of the literature review, we conducted

semi-structured conversations with multiple subject matter experts (SMEs) to better

understand memes and memetic engagement. We used these insights, along with a

selection of specific past examples, to develop an epidemiological framework to

explore memetic engagement. Drawing on this literature, semi-structured

conversations, and analysis of the meme examples, we developed a set of preliminary

observations and concluding thoughts on the applicability of memes to influence

campaigns and areas for further research.

Construct for analyzing memes

Borrowing from epidemiological models, we have identified three ways in which

memes may be situated intentionally within information and influence campaigns: to

inoculate, to infect, and to treat. We took this approach for two reasons: (1) in an

effort to retain the original concept of memes by Richard Dawkins as a pseudo-

biological concept; and (2) in order to reflect the epidemiological models applied to

the study of radicalization and terrorism. The table below provides an overview of

this construct.

Table.

Overview of the “inoculate, infect, treat” construct

Inoculate

Infect

Treat

Purpose

Prevent or minimize the

effect of adversary messaging

Transmit messages in support

of USG interests

Contain the effect of

adversary messaging

Distribution

Preventative

Anticipatory

Offensive

Stand Alone Effort

Defensive

Reactive

Message

Disposition

Adversary USG Adversary

To illustrate the application of this framework, we include a set of 14 examples that

show how visual memes have been intentionally used to inoculate, infect, or treat

information in an influence campaign. While our data set is not exhaustive, this

approach: describes and summarizes effective memetic campaigns; identifies

approaches to memetic engagement that might be replicated or imitated; and

engages with a wide variety of campaigns and actors.

v

The figure below highlights one example of what we would describe as effective

memetic engagement. A pro-Russia media outlet falsely claimed that U.S.

ambassador John Tefft had attended an opposition rally in Moscow, and

supported this claim with a photograph of Tefft in attendance (see the figure

below, left image). The U.S. embassy in Russia responded via memetic

engagement—effectively treating the Russian attempt to infect—by turning Tefft’s

image into a meme. Specifically, the U.S. embassy identified the original source of

the image, explicitly labeled it as fake news, and used Photoshop to create

their own images of Tefft in a variety of locations (see the figure below, right

image).

Figure.

Example of U.S. Embassy memetic engagement in response to Russian

disinformation regarding U.S. Ambassador Tefft

Observations from examples of memetic

engagement

Looking across our data set of meme examples, we can draw a number of preliminary

observations:

• The effective use of visual memes is not limited to counter-radicalization

efforts. While memes certainly have utility in that area, they have also been

deployed productively in response to terrorism more generally, to

disinformation campaigns, and to government censorship.

• The range of visual memes being deployed in memetic campaigns is far-

reaching. In some instances, the format is the familiar one of combining a

well-known picture with words following an established grammar. Other

vi

examples include doctoring situationally relevant images, creating brand new

images with distinct messaging, and pairing images with common cultural

references.

• Visual memes often (though not always) use humor, irony, and sarcasm in

order to resonate emotionally.

• Visual memes often transcend individual cultures and languages, and can

reach broad communities of disparate actors in the online information

environment.

• Well-targeted visual memes are culturally specific and situationally narrow.

This may seem to be a direct contradiction of the previous observation, but it

is important to acknowledge that while memes may be understood across wide

swaths of humanity, they will likely be particularly meaningful within specific

cultures, languages, and situations.

• Visual memes are utilized by all manner of online actors—governments,

non-governmental organizations (NGOs), non-state actors, and individuals.

• Visual memes have been used effectively at the tactical level (e.g.,

combatting local government censorship) and the strategic level (e.g.,

against North Korean missile tests).

Observations from discussions with SMEs

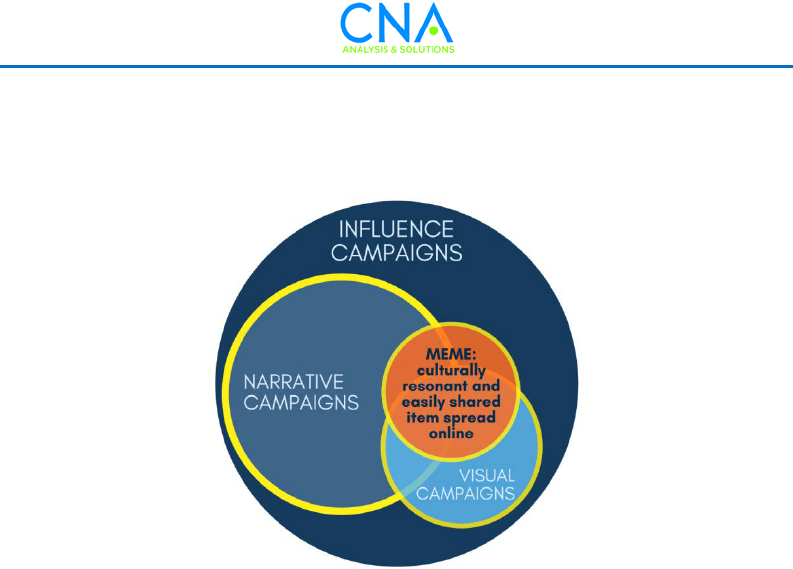

In examining the roles of memes and memetic engagement, we conducted semi-

structured conversations with members of the USG influence community, as well as

academic and private sector experts and practitioners in marketing, advertising, and

psychology (to include a professional internet troll). Based on these conversations,

we make several observations regarding the potential applicability of memes to

influence campaigns. First, using memes effectively as part of such campaigns is

neither predictable nor formulaic—significant cultural, contextual, and experiential

knowledge is required, as is granular understanding of the intended audience.

Second, contrary to popular belief, virality of a meme is not necessarily correlated

with its persuasive power, and changes in people's attitudes do not

necessarily correlate to changes in their behavior. As a result, while memes can be

useful across the range of USG influence activities, they are likely to have the

most effect when used as a complementary part of a broader campaign that

includes other approaches to influence (e.g., diplomatic and face-to-face

engagement). The figure below illustrates how memetic engagement fits within

broader engagement activities.

vii

Figure.

How memes and memetic engagements fit into influence campaigns

In conclusion, we find that memes do have significant potential for enhancing USG

influence campaigns but that additional research on memetic engagement can

provide a better understanding of how to employ them most effectively. We suggest

the following topics for additional research:

• What constitutes an effective memetic engagement? What type of visual,

digital, and cultural information might one need to create an effective

memetic engagement? How would this differ from the information needed to

inform a traditional USG influence campaign?

• What can an effective memetic campaign accomplish? What makes a

campaign effective? How can we assess and evaluate the use of memes?

• Who are the appropriate USG entities to lead the creation, dissemination, and

evaluation of the use of memes?

• How much utility do memes have in shaping operations, in competition short

of armed conflict, in irregular warfare, and in major combat operations? How

and why might their utility and usage need to change across these activities?

We bel

ieve that visual memes and memetic engagement are tools with great potential

for the USG as it looks to counter the information activities of state and non-state

actors and more proactively engage audiences online. But we also believe that

considerable additional research should be undertaken in order to ensure that the

USG is maximally effective in the use of these tools.

viii

Figure. Morpheus on the report following this executive summary

S

ource: imgflip Meme Generator, https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, accessed March

24, 2018.

ix

Contents

Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1

Research approach ................................................................................................................ 2

Organization ........................................................................................................................... 3

What are Memes? ......................................................................................................................... 4

Early definitions and theories ............................................................................................ 4

Modern interpretations ........................................................................................................ 6

Defining a meme ................................................................................................................. 11

Why Visual Memes are Useful Tools for Influence .......................................................... 12

Examples of Visual Memes and Observations on their Use for Influence ................ 15

Inoculate ................................................................................................................................ 17

Exemplar: Japanese citizens respond to the Islamic State .................................. 17

Supporting example: North Korean nuclear program .......................................... 21

Supporting example: Mexico responds to ISIS threat ........................................... 22

Supporting example: Spain responds to ISIS threat.............................................. 23

Infect ...................................................................................................................................... 24

Exemplar: Nahdlatul Ulama Responds to ISIS ........................................................ 24

Supporting example: Russian interference in Brexit ............................................ 27

Supporting example: Russian interference in U.S. presidential election .......... 29

Supporting example: ISIS spreads brand via @ISILCats ....................................... 30

Supporting example: 4Chan mocks ISIS with rubber ducks ............................... 32

Supporting example : #DAESHbags anti-ISIS campaign ....................................... 33

Treat ....................................................................................................................................... 34

Exemplar: U.S. Embassy Response to Russian Disinformation .......................... 34

Supporting example: Response to Italian government’s censorship ................ 39

Supporting example: Response to Catalan government’s disinformation ....... 41

Preliminary observations ................................................................................................... 42

Observations from Subject Matter Expert Discussions .................................................. 44

x

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................. 47

Suggestions for further research ..................................................................................... 48

Appendix: A History of “Memetic Warfare” ....................................................................... 50

Appendix B: Organizations and Individuals Contacted .................................................. 56

References ................................................................................................................................... 57

xi

List of Figures

Figure 1. Success Kid on Memes .................................................................................... 1

Figure 2. Dancing Baby meme ........................................................................................ 7

Figure 3. Some popular modern memes ...................................................................... 7

Figure 4. Memes combining images and text .............................................................. 8

Figure 5. Success Kid, original ....................................................................................... 9

Figure 6. Success Kid template ...................................................................................... 9

Figure 7. Success Kid memes ....................................................................................... 10

Figure 8. Summary of examples .................................................................................. 17

Figure 9. Examples of Japanese anti-ISIS memes ..................................................... 19

Figure 10. Examples of Japanese anti-ISIS memes: al-Baghdadi as “Chubby

Bubbles Girl” ................................................................................................... 20

Figure 11. Examples of responses to North Korean missile launch ....................... 21

Figure 12. Example of Mexico’s response to ISIS threats .......................................... 22

Figure 13. Example of Spanish reponse to ISIS threats ............................................. 24

Figure 14. Examples of NU responses to ISIS .............................................................. 26

Figure 15. Examples of responses to Russian interference in Brexit ..................... 28

Figure 16. Examples of Russian memes used to disrupt the U.S. Presidential

election ............................................................................................................. 30

Figure 17. Examples of “mewjahid” memes ................................................................ 31

Figure 18. Example of 4Chan anti-ISIS ducks .............................................................. 32

Figure 19. Examples of # Daeshbags campaign .......................................................... 34

Figure 20. Example Russian disinformation regarding U.S. Ambassador Tefft ... 36

Figure 21. U.S. embassy response to Russian disinformation ................................. 37

Figure 22. More examples of U.S. embassy response to Russian

disinformation ................................................................................................ 37

Figure 23. Russian Twitter users’ response to Russian disinformation ................ 38

Figure 24. Examples of Italian response to censorship ............................................ 40

Figure 25. More examples of Italian response to censorship .................................. 41

Figure 26. Example of response to Catalan disinformation ..................................... 42

Figure 27. How memes and memetic engagements fit into influence

campaigns ....................................................................................................... 48

Figure 28. Leonardo DiCaprio meme on the end of this report .............................. 49

xiii

Glossary

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

DOD Department of Defense

DOS Department of State

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigations

GIF Graphics Interchange Format

IC Intelligence Community

ISIS Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

NU Nahdlatul Ulama

SME Subject Matter Expert

USG United States Government

VORTEX Vienna Observatory for Applied Research on Radicalism

and Extremism

1

Introduction

If you have been online in the past year—if you have connected to the internet via a

desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone; if you have been on Facebook, Twitter,

Tumblr, Instagram, or any social media platform; or if you have an email account and

know someone inclined to pass along funny forwards—then you have almost

certainly seen a meme. There are thousands in circulation (the website Know Your

Meme lists over 4,000 “confirmed meme entries”), and new ones are being created

weekly.

1

Some have been around for nearly a decade, while others have been around

for a matter of days; some have broad appeal and can be found in relatively

mainstream online communities, while others are relatively niche and might circulate

only within closed online communities. One particularly popular example is that of

Success Kid, depicted in Figure 1 and discussed in detail later in this report.

Figure

1. Success Kid on Memes

Source:

imgflip Meme Generator, https://imgflip.com/memegenerator

, accessed March

22, 2018

1

“Meme Database,” Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes, accessed March 22,

2018.

2

While these images are popularly known as “memes,” a closer look at the concept

reveals a nuanced, contested, and complex set of ideas worthy of further inquiry. The

term has multiple active definitions; it has been invoked for decades by analysts

exploring its utility to the civilian and governmental influence communities; and it

has been mentioned recently in the context of online radicalization campaigns by the

Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Russia’s disinformation activities. In short,

the very concept of meme remains contested and yet there is an increasingly long list

of reasons compelling us to turn our attention to the role of memes in

shaping public discourse, to the capacity of memes to affect individual

attitudes and behaviors, and to the utility of memes as part of influence

campaigns—which we are referring to as memetic engagement.

In light of these trends, CNA initiated an exploratory study on the applicability,

utility, role, and value of memes and memetic engagement in USG influence

campaigns. Our hope is that this study will further the conversation on memetic

engagement within the U.S. government (USG) influence community, including policy-

makers and military leaders, as they explore novel and innovative approaches

to develop and employ strategies to counter state and non-state actors

in the online information environment.

Specifically, this study addresses the following questions:

• What are memes? What is the history of memes?

• How and why do memes affect individual and organizational attitudes and

behaviors? How and why do concepts such as virality and persuasion relate to

communication via memes (i.e., “memetic communication”)?

• Can memes and memetic engagement be useful in USG influence campaigns to

counter state and non-state actors? Does memetic engagement fit into USG

influence campaigns across the spectrum of conflict and range of activities?

• What type of framework can be used to design effective memetic engagement?

Research approach

This study was conducted in five steps:

1. We conducted a comprehensive literature review on the background and

history of memes, memetic engagement, and memetic warfare, starting from

the first articulation of the idea in 1976 and moving to the present. We used

3

this literature review to develop themes and insights that served as a

foundation for the study.

2. We reviewed psychology and marketing literature to gain insights on whether

memetic virality could be linked to changes in attitudes and behaviors, and

whether memetic communication was well suited to the work of persuasion.

3. We conducted semi-structured conversations with subject matter experts

(SMEs) across the influence community—to include the U.S. Departments of

Defense and State (DOD and DOS, respectively), the intelligence community

(IC), academia, marketing, and advertising—to further extrapolate, assess, and

validate our preliminary insights on memes and memetic engagement, virality

and persuasion, and the applicability and utility of memes and memetic

engagement in USG influence campaigns.

4. We used these insights along with a set of epidemiological models to develop a

framework to explore memetic engagement through a series of examples. Our

framework classifies these examples into three categories: inoculate, infect, and

treat. While additional models exist that explore memetic and online

engagement, including the concept of memetic warfare as discussed in the

appendix, our exploratory research suggests that epidemiological models

prove a sound way to explore the utility of memes in influence campaigns.

5. Drawing on the literature review, semi-structured conversations, and analysis

of these cases, we developed a set of preliminary observations from our

interviews with subject matter experts, along with concluding thoughts on the

applicability of memes to influence campaigns and ideas for further research.

Organization

This report is structured into six sections. First, we explore the concept of memes

—examining original, current, and popular usages; offering our own definition of

meme; and analyzing the relatively modest existing literature on the

operationalization of memes. Second, we explore why memes are a useful

tool for influence campaigns. Third, we present our concept for

operationalizing memes through the epidemiological framework of

inoculate, infect, and treat as depicted through select examples. Fifth, we

offer preliminary observations from subject matter experts on memetic

engagement. Sixth, we conclude with thoughts on the applicability of memes

to influence campaigns and ideas for future research.

4

What are Memes?

Early definitions and theories

In 1976, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins suggested that ideas could be

transmitted between people in much the same way that physical characteristics are

transmitted between people. In this model, memes—small bits of cultural

information, to include slogans, stories, fairytales, songs, jokes, beliefs, concepts,

and worldviews—are transferred between people via interpersonal and social

interactions. Importantly, Dawkins’ model of idea transmission (i.e., memetic

transmission) suggested that the persistence and spread of individual memes was

the product of an evolutionary process. He asserted that memes are self-replicating

in that the popularity or success of a meme ensures that it will be passed on in a

process that sometimes involves evolution and mutation: “If a scientist hears, or

reads about, a good idea, he passes it on to his colleagues and students. He mentions

it in his articles and lectures. If the idea catches on, it can be said to propagate itself,

spreading from brain to brain.”

2

Additionally, he argued that memes are subject to

copying error, variation, and mutation. In other words, memetic transmission

involves some of the core components of Darwin’s evolutionary process: variation,

replication, and natural selection.

Since Dawkins’ groundbreaking coining of the term, the concept of meme has

evolved considerably. Early work began with the idea that a meme was a bit of

cultural information that could be passed “from brain to brain,” and the concept was

used to explore how knowledge might be transmitted between individuals.

3

The

discipline of memetics, which took shape in the mid-1980s, built directly on

Dawkins’ work to explore the idea that evolutionary models explained cultural

information transfer between people and through generations. While some work on

this topic emphasized that memes were passed via human imitation (and Dawkins’

original definition emphasized this point), other scholarship posited that the

transmission of ideas could be best understood via an epidemiological model that

2

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989).

3

Ibid.

5

foregrounded contagion. In this line of thinking, ideas could essentially “infect”

individuals and societies in the same way that viruses infect a host. In short, two

models took shape: one in which memes were passed via the act of human imitation,

and one in which memes spread through a population as a contagion.

4

More interesting than the imitation/contagion debate was work that focused on what

made a specific meme successful. In other words, in an evolutionary environment

shaped by natural selection ensuring the survival of the fittest, it was important to

identify what made a meme fit. Different models were offered, but the same core

themes emerged in each. One researcher argued, for example, that a successful

meme went through four stages: assimilation, retention, expression, and

transmission. In other words, a successful meme is:

• Assimilated: a person needs to notice the meme, understand the meme, and

internalize the meme.

• Retained: a person needs to remember the meme (a process that is influenced

by “the uniqueness of the meme, frequency of presentation, authority of the

source, how easy it is to express, consistency with norms of a culture, and its

usefulness to an individual”).

• Expressed/Transmitted: a person needs to publicly express the meme so that it

can be transmitted to another person.

5

This e

arly approach to meme fitness focused on the factors related to transmission

of knowledge. Later research shifted the focus by exploring the work in cognitive

psychology and information processing theory to ask “how [memes] leave lasting

footprints.”

6

One article concluded that meme fitness could be explained in terms of

four criteria: “(1) In terms of a meme’s compatibility with the brain’s hardwiring (2)

4

Additional work explored the role that memes played in human evolution, suggesting that a

robust theory of memetic replication might account for human brain size or serve as an

explanation for the development of human language. In this more aggressive framework,

memes might be more important than genes: “Successful memes would begin dictating which

genes would be most successful. The memes take hold of the leash.” This theory is, however,

neither prominent nor widely accepted. For an outline of this argument, and a series of

counterarguments, see Susan Blackmore, “The Power of Memes,” Scientific American 283, no. 4

(October 2000): 64-73.

5

Francis Heylighen, “What makes a meme successful? Selection criteria for cultural evolution,”

paper presented at the 15th International Congress on Cybernetics, Namur, Belgium (1998,

August), quoted in Gideon Mazambani et al., “Impact of Status and Meme Content on the

Spread of Memes in Virtual Communities,” Human Technology 11 (2015).

6

Richard J. Pech, “Memes and cognitive hardwiring: Why are some memes more successful than

others?” European Journal of Innovation Management 6.3 (2003): 174.

6

By the ease with which the meme can be replicated… (3) By a meme’s ability to

provide for or meet the needs of the people it encounters… (4) By an accidental or

involuntary lodging of a meme or a part of a meme in the neural network.”

7

Modern interpretations

Little is published these days on the traditional understanding of memetics described

above, and the term has evolved to such a degree that the mention of meme no

longer brings to mind the work of Dawkins. Instead, the term has seen something of

a rebirth in the age of the internet and, as Merriam-Webster notes, a meme is now

popularly defined as “an amusing or interesting item or genre of items that is spread

widely online especially through social media.” As Dawkins himself noted in 2013:

The very idea of the meme, has itself mutated and evolved in a new

direction. An internet meme is a hijacking of the original idea. Instead

of mutating by random chance, before spreading by a form of

Darwinian selection, internet memes are altered deliberately by

human creativity. In the hijacked version, mutations are designed—

not random—with the full knowledge of the person doing the

mutating.

8

Today the concept of meme is broadly understood to mean one of two things. In

some instances, it might refer to a piece of cultural information that is shared or

spread online: an image, video, hashtag, a Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) image,

or textual statement. An early example would be Dancing Baby (1996), as shown in

Figure 2.

7

Richard J. Pech, “Memes and cognitive hardwiring: Why are some memes more successful than

others?” European Journal of Innovation Management 6.3 (2003): 179.

8

R. Dawkins (Performer) and Marshmallow Laser Feast (Director) (2013), Just for Hits. Available

at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFn-ixX9edg, quoted in Bradley E. Wiggins and G. Bret

Bowers, “Memes as Genre: A Structurational Analysis of the Memescape,” New Media & Society

17.11 (2015): 1886-1906.

7

Figure

2. Dancing Baby meme

Source:

Dancing Baby, Know Your Meme

, accessed March 7, 2018,

http://knowyourmeme.com/

memes/dancing-baby.

More recent, but similarly popular examples, include those shown in Figure 3.

Figure

3. Some popular modern memes

Note:

Keyboard Cat (top left, 2007); Charlie Bit My Finger (top right, 2007), Kanye Interrupts

(

bottom left, 2009), Make A Wish’s #SFBatkid (bottom right, 2013).

Source:

Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes, accessed March 7, 2018.

In other instances, and more commonly, the word meme doesn’t refer to a “simple

stand-alone artifact [but to] a full-fledged genre…with its own set of rules and

8

conventions.”

9

In these cases, the meme—typically an image accompanied by text of

some sort—develops its own grammar as it spreads: the image/meme conveys a

specific message, and informal rules dictate what words/quotes can be meaningfully

superimposed on the image. Such memes constitute a “shared cultural language”

that often transcends the internet, ensuring that broad parts of the general

population understand what is being communicated.

10

Examples of this type of

meme abound and include those shown in Figure 4.

Figure

4. Memes combining images and text

Note:

Grumpy Cat (left), Philosoraptor (center), The Most Interesting M

an in the World

(right).

Source:

Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes, accessed March 7, 2018

;

imgflip

Meme Generator, https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, accessed March 22, 2018.

Critically, in each instance the core image is replicated by individuals who customize

it to communicate distinct messages. Thus, these memes are not merely viral images

shared online. They are, instead, a type of communication. These image-based

expressions are persistent, in part due to the participatory nature of their

construction.

11

A meme, in other words, has an organic lifestyle that approximately

follows the progression described below.

First, a single image is posted online. In the case of the Success Kid meme, the

original was a 2007 photo of 11-month-old Sammy Griner, as shown in Figure 5:

9

Bradley E. Wiggins and G. Bret Bowers, “Memes as Genre: A Structurational Analysis of the

Memescape,” New Media & Society 17.11 (2015): 1886-1906.

10

Marion Provencher Langlois, “Making Sense of Memes: Where They Came From and Why We

Keep Clicking Them,” Inquiries Journal 6.03 (2014).

11

Bradley E. Wiggins and G. Bret Bowers, “Memes as Genre: A Structurational Analysis of the

Memescape,” New Media & Society 17.11 (2015): 1886-1906.

9

Figure

5. Success Kid, original

Source:

Success Kid, Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/success-kid-i-

hate

-sandcastles, accessed March 7, 2018.

The image is then modified—in this instance, Sammy was photo-shopped onto a

purple background, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure

6. Success Kid template

Source:

Success Kid, Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/success-kid-i-

hate

-sandcastles, accessed March 7, 2018.

Finally, the meme was replicated extensively by a community that organically agreed

upon a basic syntax, as shown in Figure 7.

10

Figure

7. Success Kid memes

Source:

Success Kid, Know Your Meme, http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/success-kid-i-

hate

-sandcastles, accessed March 7, 2018.

In both contemporary cases—whether meme refers broadly to a piece of cultural

information shared online, or narrowly to a specific image with accompanying text—

the meme is culturally relevant, broadly resonant, organically developed, and

voluntarily spread. These memes are, returning to the language of Dawkins, bits of

cultural information that survive via replication, mutation, and natural selection.

Thus, despite the significant shift away from early models and the language of

Dawkins (i.e., models suggesting that memes mutated randomly), many of the core

ideas developed by early thinkers remain relevant (i.e., questions about meme fitness

and selection are still important). What makes these contemporary memes unique is

simply that this process is intentional and purposeful, and that the memes

themselves exist primarily in a virtual world.

Importantly, work on memes has consistently been somewhat controversial and

contested. It has evolved considerably, from being articulated in models that

foreground imitation, and in models that focus on contagion; to being applied to

human biological evolution, and to the spread of information; to referencing all types

of cultural information, and a narrow subset that appears online. And at times it has

been taken up by thinkers that exist at the fringes of reputable science. One relatively

recent article acknowledged this messy history quite clearly:

Memetics, the study of meme theory and application, is a kind of grab

bag of concepts and disciplines. It's part biology and neuroscience,

part evolutionary psychology, part old fashioned propaganda, and

11

part marketing campaign driven by the same thinking that goes into

figuring out what makes a banner ad clickable. Though memetics

currently exists somewhere between science, science fiction, and

social science, some enthusiasts present it as a kind of hidden code

that can be used to reprogram not only individual behaviors but

entire societies.

12

As this article notes, the question of how a meme functions—or what conceptual or

practical value might come from the study of these processes—is not yet settled.

Memes are, however, unquestionably ubiquitous and it thus seems clear that a robust

engagement with the concept is critical. Understanding the history of the term

informs this process, but the messy nature of the literature on memes makes it

particularly important to accurately define and situate the concept.

Defining a meme

For the purpose of this exploratory study, we have adopted the following functional

definition:

A meme is a culturally resonant item easily shared or spread online.

Of note, this definition is not exclusively visual, as memes can (and do) consist of

non-visual items (e.g., a hashtag campaign). However, in the remainder of this paper

we will focus on visual memes.

13

The decision to do this was motivated primarily by

available resources. Defined most inclusively a meme is an idea, but an analysis

of how ideas are important for influence campaigns was clearly too broad in

scope. Additionally, we recognize that currently the term meme brings to mind

funny images spread online (e.g., Grumpy Cat, Success Kid). This, combined with

the shift (discussed in more detail below) to increasingly visual communication

online, led us to focus our attention on the use of visual memes.

The reality that memes are ubiquitous does not, however, necessarily mean that they

are an effective vehicle via which to engage in influence campaigns. As a result, it is

necessary to consider both whether and how memes might be an important addition

to activities and programs already underway. We do this in the sections that follow.

12

Jacob Siegel, “Is American Prepared for Meme Warfare?” Motherboard VICE (Jan 2017),

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/xyvwdk/meme-warfare.

13

We are not, in other words, focused on memes that are textual (hashtags, slogans, etc.),

musical (jingles, theme songs, pop hits, etc.), narrative (fairy tales, urban legends, etc.), and the

like.

12

Why Visual Memes are Useful Tools

for Influence

Across the fields of psychology, behavioral sciences, philosophy, and marketing, the

literature agrees that images offer some advantages over text. These advantages—

particularly those with respect to brevity and stickiness—make visual memes

especially well-suited for influence campaigns. One advantage that memes have in

influence campaigns is that they consist of perceptual information. In other words,

they communicate information beyond the composition of the image itself. This

intuited, or connotatively conveyed, information means that images take less time to

consume than text and allow us to communicate complex concepts quickly.

14

Further, advertising, marketing, and psychological research suggest that visual cues

take advantage of heuristics, which enable our brains to retrieve information related

to images more quickly than information related to text. Indeed, neurocognitive

research confirms that the human brain is predominately an image processor whose

sensory cortex is far larger than its word processing centers.

15

This reliance on

heuristics is particularly acute for information presented online: technology

increases reliance on heuristics, which reduces the likelihood that consumers will

think deeply.

16

As a result, a rational discussion of an issue (e.g., an article exploring

corruption in the upper tiers of the Islamic State) will be less effective than a visual

campaign (e.g., a memetic engagement discrediting the group).

Finally, images tend to be emotionally evocative. In the visual domain, research has

shown that emotional cues (both offensive and appetitive) are preferentially

14

Peter J. Lang, A Bio-Informational Theory of Emotional Imagery (Madison, WI: Society for

Psychophysiology, University of Wisconsin, September 1978),

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1979.tb01511.x/full; and David Kieras,

“Beyond Pictures and Words: Alternative Information Processing Models for Imagery Effects in

Verbal Memory,” Psychological Bulletin 85, no. 3 (1978): 532-554.

15

Haig Kouyoumhjian, “Learning through Visuals: Visual Imagery in the Classroom,” Psychology

Today, July 2012, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/get-psyched/201207/learning-

through-visuals.

16

Semi-Structured Discussion with Fellow, Social Innovation Lab, Stanford University, January

10, 2018.

13

processed in the brain.

17

Interestingly, research suggests that emotion can be elicited

subliminally, suggesting that we do not need to be aware of why we feel a certain way

for our attitudes and behaviors to be affected. The stickiness of emotionally

evocative information and the effectiveness that images produce in eliciting these

emotional responses creates a message efficacy that textual means of

communication lack.

18

In combination, research exploring these ideas suggests that

visual memes are particularly strong vehicles for communication.

While this behavioral science work is compelling, so is marketing research, which

suggests that a failure to engage memetically effectively cedes a massive

communications forum to those who are doing this work (e.g., state actors, non-state

actors, citizens, etc.). To begin, the visual online arena is growing rapidly. A recent

article in a marketing magazine suggests that over 80 percent of communications

will soon be visual, and that visual content has overtaken textual content in terms of

consumer engagement.

19

Additionally, a marketing website notes that readers engage

with relevant infographics more than with the surrounding text (i.e., choosing the

easily processed over the cognitively demanding).

20

The same site also notes that images are liked and shared three times more

frequently than other types of online content; that images radically increase the

likelihood that someone will accurately follow instructions (people perform over 300

percent better with accompanying images); and that images significantly improve

information retention (information paired with an image was retained for longer than

information presented alone).

21

Data analysis also suggests that in some instances

visual content has meaningfully influenced behavior as people were more likely to

17

Antje BM Gerdes, Matthias J Wieser, and Georg W Aplers, “Emotional Pictures and Sounds: A

Review of Multi Modal Interactions of Emotion Cues in Multiple Domains,” Frontiers in

Psychology, December 2014, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/

fpsyg.2014.01351/full.

18

Kirsten I. Ruys and Diederik A. Stapel, “The Secret Life of Emotions,” Psychological Science 19

(4) (2008): 385; Association for Psychological Science, Cause and Affect: Emotions Can Be

Unconsciously and Subliminally Evoked, Science Daily Review (April 2008),

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/04/080428155208.htm.

19

Larry Kim, 16 Eye-Popping Statistics You Need to Know About Visual Content Marketing, INC

Online, November 2015, https://www.inc.com/larry-kim/visual-content-marketing-16-eye-

popping-statistics-you-need-to-know.html.

20

Jesse Mawhinney, 42 Visual Content Marketing Statistics You Should Know in 2017, Hubspot

Online, February 2018, https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/visual-content-marketing-strategy

21

Ibid.

14

purchase a product if the advertisement was a video.

22

In other words, online visual

engagement is growing, and increasingly sophisticated tools and metrics for

engaging in this forum now exist. Thus, it appears that there are considerable

reasons for further exploration of the use of memes as part of influence campaigns.

In the next section, we will present a number of specific examples of the use of visual

memes for various influence purposes.

22

Larry Kim, 16 Eye-Popping Statistics You Need to Know About Visual Content Marketing, INC

Online, November 2015, https://www.inc.com/larry-kim/visual-content-marketing-16-eye-

popping-statistics-you-need-to-know.html.

15

Examples of Visual Memes and

Observations on their Use for

Influence

Borrowing from epidemiological models, we have identified three ways in which

memes may be situated intentionally within information and influence campaigns: to

inoculate, to infect, and to treat. We have adopted this model for two reasons: first

and foremost, we felt that applying an epidemiological model was in keeping with

the original understanding of memes, as defined by Richard Dawkins, as a pseudo-

biological concept; and second, this model is adapted from the existing body of

literature related to radicalization and terrorism wherein epidemiological models

have been applied in a number of studies to the transmission of radical and

extremist narratives. In light of this study’s limited scope, we synthesized and

distilled the existing literature’s concepts into inoculate, infect, and treat categories.

Table 1 below provides a brief overview of this construct.

Table 1. Overview of the “inoculate, infect, treat” construct

Inoculate

Infect

Treat

Purpose

Prevent or minimize the

effect of adversary messaging

Transmit messages in support

of USG interests

Contain the effect of

adversary messaging

Distribution

Preventative

Anticipatory

Offensive

Stand Alone Effort

Defensive

Reactive

Message

Disposition

Adversary USG Adversary

Primary sources used to develop this concept below; additional sources in references section

23

23

Kenrad E Nelson. Epidemiology of Infectious Disease: Theory and Practice, 3

rd

Edition

(Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishing, 2014); Mauricio Barreto, Maria Gloria Teixeira,

and Eduardo Hage Carmo, “Infectious Diseases Epidemiology,” Journal of Epidemiology and

Community Health 60, No. 3 (March 2006): 192-195,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2465549

16

To highlight and illustrate the application of this framework, we include a set of

examples below that show how visual memes have been used to inoculate, infect, or

treat information in an influence campaign. These examples were identified

as effective in part via an application of the concept of meme fitness (discussed

above): they were assimilated (i.e., they were noticed and understood); they were

retained (i.e., they were remembered enough to engender engagement); and

they were expressed or transmitted (i.e., relevant images were shared and posted

publicly).

24

In short, we take the examples below to be examples of effective

memetic engagement for three reasons: (1) they were targeted to a specific issue, (2)

they resonated with a relevant population, and (3) they were fit enough to gain

traction (both in the form of memes posted, and in the form of mainstream media

coverage). These examples are not exhaustive, but represent a sample of cases

from which we can gain greater insights into the applicability and

operationalization of memes in influence campaigns.

Our research suggests that the epidemiological approach has unique value because it

is descriptive, prescriptive, and inclusive: this approach offers a clear summary of

effective memetic campaigns; it identifies approaches to memetic engagement that

might be replicated or imitated; and it capaciously engages with a wide variety of

campaigns and actors. Figure 8 on the next page summarizes the examples we

discuss—showing the range of issues and environments in which memetic

engagement has been used.

Randy Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A Review of Conceptual Models and

Empirical Research,” Journal of Strategic Security 4, No. 4 (Winter 2011): 37-62,

http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1140&context=jss.

24

Francis Heylighen, “What makes a meme successful? Selection criteria for cultural evolution,”

paper presented at the 15th International Congress on Cybernetics, Namur, Belgium (1998,

August), quoted in Gideon Mazambani et al., “Impact of Status and Meme Content on the

Spread of Memes in Virtual Communities,” Human Technology 11 (2015).

17

Figure

8. Summary of examples

Source:

CNA

Inoculate

To use a meme in an effort to protect against a threat or anticipated

attack. Using memes to preemptively address—with an emphasis on

delegitimizing or undermining—a message or attack expected from

another actor.

Exem

plar: Japanese citizens respond to the Islamic

State

Actor: Japanese citizens

Message: Anti-ISIS

Target Population: ISIS, Japanese people

On January 20, 2015, ISIS released a video featuring Japanese prisoners Kenji

Goto and Haruna Yukawa. The video functioned as a ransom request: the

militants demanded that the Japanese government pay $200 million in order

to secure the hostages’ release.

25

The video also included a message to the

Japanese public:

18

To the Japanese public, [..] you now have 72 hours to pressure your

government into making a wise decision by paying $200 million to save

the lives of your citizens.... Otherwise, this knife will become your

nightmare.

26

The Japanese public, however, did not cooperate with ISIS’s request. Instead, they

embraced a hashtag that translated to “ISIS Crappy Photoshop Grand Prix,” and

embarked upon an aggressive campaign mocking ISIS and the armed militant

featured in the video.

27

Importantly, this hashtag campaign—which included a

significant memetic engagement—aspired in part to inoculate the Japanese

public against the expected horror of the hostages being executed.

The hashtag campaign was varied and far reaching, and included a significant

number of memes. Many of these were iterations of a specific image (in this case, a

screenshot of the hostages and militant taken from ISIS’s video). Some of

the responses were culturally specific, and referenced Japanese gaming, kawaii,

and anime culture; and some were more universally accessible and referenced Star

Wars, cats, and global politics.

28

Some sample memes are shown in Figure 9.

25

Martin Fackler and Alan Cowell, “Hostage Crisis Challenges Pacific Japanese Public,” New

York Times, January 20, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/21/world/middleeast/video-

isis-japanese-hostages.html?_r=0.

26

Ibid.

27

Alicia Lu, “Japan Trolls ISIS On Twitter With Memes In A Defiant, Passionate Show Of

Resistance,” Bustle, January 23, 2015, https://www.bustle.com/articles/60218-japan-trolls-isis-

on-twitter-with-memes-in-a-defiant-passionate-show-of-resistance.

28

@deepquest, “#ISISクソコラグランプリ. #Caturday #ISIS,” January 24, 2015,

https://twitter.com/deepquest/status/559015796127444994; @dedeyudistira, “

Tongsis rek RT

@Mosesofmason: ‘@MFugicle: ‘@temmo5: #ISISクソコラグランプリ ‘even Isis likes to keep it

trendy,’’” January 24, 2015, https://twitter.com/dedeyudistira/status/559054832661569536;

@raktvru, “Reimu owned! #ISISクソコラグランプリ

,“ January 21, 2015,

https://twitter.com/raktvru/status/558025030710599680; @tokyoscum, “ISIS threatens to

execute two Japanese hostages, becomes Photoshop meme: #ISISクソコラグランプリ,”

January 20, 2015, https://twitter.com/tokyoscum/status/557708538282512384;

@Mitch_Hunter, “#ISISクソコラグランプリ #ISIS This has to be my favorite so far. Might be

time to make a few myself ;),” January 22, 2015,

https://twitter.com/Mitch__Hunter/status/558480504874598400; @Top_kek_3,

“@PelayoKnoxville #ISISクソコラグランプリ,” January 21, 2015,

https://twitter.com/Top_kek_3/status/558038543222984704.

19

Figure

9. Examples of Japanese anti-ISIS memes

Source: See footnote 2

8.

Importantly, not all of the memes that circulated as part of this hashtag campaign

were iterations of the original screenshot from the video. Some were simply tapping

into the ethos of the campaign, but relying on other imagery. One such example of

this was a meme that circulated under this hashtag, but which used alternative

imagery, and was an iteration of a widely circulated American meme that dated to

2009. In the new meme, ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was featured as “Chubby

Bubbles Girl” and shown fleeing a tiger.

29

See Figure 10.

29

Know Your Meme, “Chubby Bubbles Girl,” http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/chubby-

bubbles-girl; @sutesute60, “Baghdadi getaway バグダディ逃走中。 #ISIS #IS #ISISクソコラグラ

ンプリ #iraq #Syria #jihād,” Febuary 18, 2015, https://twitter.com/sutesute60/

status/568071190524227584.

20

Figure

10. Examples of Japanese anti-ISIS memes: al-Baghdadi as “Chubby Bubbles

Girl”

Source: See footnote 2

9.

Ultimately, the fate of the hostages was not influenced by this memetic response.

The Japanese government did not pay the ransom, and by the end of the month, ISIS

had released videos showing the men being beheaded. Without minimizing this

tragedy, it is possible to recognize that the memetic campaign surrounding it was

incredibly effective. The hashtag was used more than 200,000 times in the days after

the ISIS video was posted (and is, in fact, still in use in early 2018).

30

And while the

campaign provoked controversy, it was effective in undermining the ultimate goal of

the terrorist movement by casting them as preposterous rather than powerful and

threatening. The campaign permitted the Japanese people to take control of the

narrative and “[deflate] ISIS's formidable image.”

31

As one Twitter user posted (with

reference to the ransom deadline): “Tomorrow will be sad but it will pass and #ISIS

will still be a big joke. You can't break our spirit.”

32

In short, the memetic response—

inspired by screenshots from ISIS’s own video—effectively inoculated the Japanese

people. While it did not change the outcome of the beheadings, it may have helped

undermine the impact by delegitimizing ISIS and its actions.

30

“Japan Is Fighting ISIS With Super-Kawaii Tweets,” Vice, January 23, 2015,

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/8gdpvb/japan-is-fighting-isis-with-super-kawaii-tweets.

31

Alicia Lu, “Japan Trolls ISIS On Twitter With Memes In A Defiant, Passionate Show Of

Resistance,” Bustle, January 23, 2015, https://www.bustle.com/articles/60218-japan-trolls-isis-

on-twitter-with-memes-in-a-defiant-passionate-show-of-resistance.

32

Ibid.; @djvjgrrl, “Tomorrow will be sad but it will pass and #ISIS will still be a big joke. You

can't break our spirit #ISISクソコラグランプリ,” January 22, 2015,

https://twitter.com/djvjgrrl/status/558451972102045696.

21

Supporting example: North Korean nuclear program

Actor: Miscellaneous

Message: Mocking Kim Jung Un and North Korea

Target Population: Miscellaneous

In September 2016, the online community responded to North Korea’s fifth

successful nuclear test with a variety of memes mocking both the country and its

leader. The effort was not organized, and primarily relied on the somewhat generic

hashtag #NorthKorea. That said, this organic online movement appears to have been

an effort to inoculate against North Korea’s belligerent posturing and increasing

threat by delegitimizing the fear that the North Korean regime attempted to sow.

33

Images circulated online in response to North Korea’s nuclear test included screen

shots of leader Kim Jong Un, cartoons, and preexisting memes adapted to the

moment (see examples in Figure 11).

Figure

11. Examples of responses to North Korean missile launch

Source:

See Footnote 33.

The effect of this memetic effort was observed through news coverage of the hashtag

campaign that poked fun at Kim Jong Un, and it drew attention to North Korea’s

limited missile capabilities. This effort, coordinated by a disparate community of

social media users, served to effectively undermine the threat that the North Korean

regime wished to convey.

33

Rory Tingle, “Kim Jong Fun! Internet Reacts to Tubby North Korean Dictator's Latest Nuke

Test by Mocking Him with Hilarious Memes,” Daily Mail, September 9, 2015,

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3782305/Internet-reacts-tubby-North-Korean-

dictator-s-latest-nuke-test-mocking-hilarious-memes.html.

22

Supporting example: Mexico responds to ISIS threat

Actor: Mexican citizens

Message: Anti-ISIS

Target Population: ISIS, Mexican people

In 2015, ISIS released a video erroneously naming Mexico as a member of the

coalition fighting the terrorist movement and issuing a threat against the country

and its citizens. The Mexican people responded via a meme campaign—using the

hashtag #IsisEnMexico—and inoculated themselves against the group by posting a

variety of memes mocking the movement and making light of the threat. The theme

of the messages shared in response to ISIS’s threat was humorous and self-

deprecating, with many of the memes invoking Mexican cultural ideas to comment

on the nation’s preparedness, as the examples in Figure 12 illustrate.

34

Figure

12. Example of Mexico’s response to ISIS threats

Translation (right): We are ready.

Translation (left): I’m buying nuclear weapons because ISIS is in Mexico and we must

defend the motherland.”

Source:

See Footnote 34.

34

Latin Times, “ISIS in Mexico Memes: Twitter Reacts to Threat from Terrorist Group,” Latin

Times, November 25, 2015, http://www.latintimes.com/isis-mexico-memes-twitter-reacts-

threat-terrorist-group-355911; Rafa Fernandez de Castro, “Mexican Mock ISIS Terrorist Threat

With Memes and Humor,” Splinter, November 27, 2015, https://splinternews.com/mexicans-

mock-isis-terrorist-threat-with-memes-and-humo-1793853226.

23

In short, by deriding ISIS’s mistake and by making light of the threat that the group

poses to Mexico, Mexican citizens effectively inoculated themselves against the

group’s fearmongering.

35

Supporting example: Spain responds to ISIS threat

Actor: Spanish citizens

Meme Message: anti-ISIS

Target Population: ISIS, Spanish people

In August 2017, shortly after its attacks in Barcelona, ISIS released a video featuring a

Spanish-speaking extremist threatening violence against the country and promising

to avenge the deaths of Muslims killed during the 15

th

-century Spanish Inquisition.

The Spanish people responded promptly—demonstrating considerable resilience

given the recent attacks—by using memes to both undermine the threat levied

against them and to inoculate themselves against future violence. The campaign

featured a series of images mocking the movement and turning the extremist into

something of a laughingstock, as illustrated in Figure 13.

36

35

Latin Times, “ISIS in Mexico Memes: Twitter Reacts to Threat from Terrorist Group,” Latin

Times, November 25, 2015, http://www.latintimes.com/isis-mexico-memes-twitter-reacts-

threat-terrorist-group-355911; Rafa Fernandez de Castro, “Mexican Mock ISIS Terrorist Threat

With Memes and Humor,” Splinter, November 27, 2015, https://splinternews.com/mexicans-

mock-isis-terrorist-threat-with-memes-and-humo-1793853226 and Rafa Fernandez de Castro,

“Mexican Mock ISIS Terrorist Threat With Memes and Humor,” Splinter, November 27, 2015,

https://splinternews.com/mexicans-mock-isis-terrorist-threat-with-memes-and-humo-

1793853226.

36

Lucy Pasha Robinson, “ISIS Fighter Relentlessly Mocked On Spanish Twitter After Threatening

Further Violence,” Independent, August 26, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/

news/world/europe/islamic-state-fighter-el-cordobes-mocked-spanish-twitter-violence-

barcelona-attacks-muhammad-yasin-a7914366.html; Tom O’Connor, “ISIS Calls On Muslims to

Attack Spain, Becomes Top Twitter Meme,” Newsweek, August 25, 2017,

http://www.newsweek.com/twitter-blows-isis-militant-promising-more-attacks-spain-655242;

Emily Lupton, “ISIS Fighters Hilariously Mocked by Spanish Social-Media Users,” Business

Insider, August 25, 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/r-islamic-state-fighter-mocked-on-

spanish-twitter-2017-8.

24

Figure

13. Example of Spanish reponse to ISIS threats

Source: See Footnote 36.

Infect

To use a meme to spread a specific message. To use memes in order to

articulate a message—either positive (e.g., defending a value) or

negative (i.e., disparaging an institution)—that aligns with broader

mission objectives.

Exemplar: Nahdlatul Ulama Responds to ISIS

Actor: Indonesian non-profit Nahdlatul Ulama

Message: Anti-ISIS, Anti-violent Islam, Pro-moderate Islam

Target Population: Indonesian people

In 2015, the New York Times reported that Nahdlatul Ulama (NU)—an Indonesian

Muslim organization with 40-50 million members—was poised to embark upon a

campaign to counter ISIS’s extremism.

37

NU was working with the University of

Vienna in Austria (via a program called VORTEX, the Vienna Observatory for Applied

Research on Radicalism and Extremism) to prepare effective responses to ISIS’s

online propaganda. It was poised to open a “prevention center” where NU would train

“male and female Arabic-speaking students to engage with jihadist ideology and

37

Joe Cochrane, “From Indonesia, a Muslim Challenge to the Ideology of the Islamic State,” New

York Times, November 25, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/indonesia-

islam-nahdlatul-ulama.html.

25

messaging under the guidance of NU theologians who are consulting Western

academia.”

38

The movement’s approach, importantly, was not simply ideological whack-a-mole

(e.g., an ISIS message is posted, and an NU representative responds). NU has a

distinct and clear religious message. As one of the group’s leaders claimed:

“According to the Sunni view of Islam every aspect and expression of religion should

be imbued with love and compassion, and foster the perfection of human nature.”

39

More pointedly, according to the article, NU “promotes a spiritual interpretation of

Islam that stresses nonviolence, inclusiveness and acceptance of other religions.”

40

These values were to be at the center of NU’s campaign. In short, the group would

aspire to infect the population with a positive, pro-social, and moderate

conceptualization of Islam that would be inimical to ISIS’s violent extremism.

Less than a year later, in 2016, reporting indicated that NU’s social media work was

und

erway.

41

Nearly 500 NU “cyber warriors” were actively attempting to counter

ISIS’s online propaganda.

42

As one cyber warrior commented, “We try to make the

image of Islam as fun as possible. That’s why memes and tweets are the best way to

spread our ideas.”

43

He went on to note that he typically posted “silly memes that

poke fun at extremists as well as earnest text posts that extol moderate Islam.”

44

38

Krithika Varagur, “World’s Largest Islamic Organization Tells ISIS To Get Lost,” The

Huffington Post, December 3, 2015, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/indonesian-

muslims-counter-isis_us_565c737ae4b072e9d1c26bda; Joe Cochrane, “From Indonesia, a

Muslim Challenge to the Ideology of the Islamic State,” New York Times, November 25, 2016,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/indonesia-islam-nahdlatul-ulama.html.

39

Joe Cochrane, “From Indonesia, a Muslim Challenge to the Ideology of the Islamic State,” New

York Times, November 25, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/indonesia-

islam-nahdlatul-ulama.html.

40

Ibid.

41

In fact, NU’s social media efforts were just one facet of a broader campaign that included a

documentary film, several websites, an Android app, TV broadcasts, and conferences.

42

“Indonesia’s Muslim Cyber Warriors Take On ISIS,” The Strait Times, May 8, 2016,

http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/indonesias-muslim-cyber-warriors-take-on-isis.

43

Krithika Varagur, “Indonesia’s Cyber Warriors Battle ISIS With Memes, Tweets and

WhatsApp,” The Huffington Post, June 9, 2016,

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/indonesia-isis-cyber-

warriors_us_5750779ae4b0eb20fa0d2684?ir=Technology§ion=us_technology&utm_hp_ref=

technology.

44

Ibid.

26

Examples of NU postings are difficult to identify as the group is still modestly sized

and operating almost entirely in the Indonesian language. Some example posts have,

however, been reported in the Western media, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure

14. Examples of NU responses to ISIS

Translation (center): “Keep your worship secret the same way you conceal your

abominations.”

Translation (left):

“It’s not important what your religion is…if you do something good for all

mankind, people will never ask you.” And “Yes, religion keeps us away from sin, but how

many sins do we commit in the name of religion?”

Source:

Krithika Varagur, “Indonesia’s Cybe

r Warriors Battle ISIS With Memes, Tweets and

WhatsApp,”

The Huffington Post

, June 9, 2016,

h

ttps://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/indonesia-isis-cyber-

warriors_us_5750779ae4b0eb20fa0d2684?ir=Technology§ion=us_technology&utm_hp_

ref=technology.

The NU movement remains small compared to the sophisticated social media

campaign being coordinated by ISIS itself.

45

That said, as a terrorism expert from the

Indonesian Muslim Crisis Center noted, “It's a good strategy to make Google searches

fill up with moderate Islamic content…The battleground for Islamic ideology has

moved to the Internet, and by producing as many moderate websites as they can,

they can keep more minds healthy.”

46

In short, NU aims to “set a ‘perimeter’ around

aggressive Islam so that it doesn’t spread beyond those who are already

radicalized.”

47

Its goal is to articulate a moderate Islamic message, or, in other words,

45

“Indonesia’s Muslim Cyber Warriors Take On ISIS,” The Strait Times, May 8, 2016,

http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/indonesias-muslim-cyber-warriors-take-on-isis.

46

Ibid.

47

Krithika Varagur, “Indonesia’s Cyber Warriors Battle ISIS With Memes, Tweets and

WhatsApp,” The Huffington Post, June 9, 2016,

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/indonesia-isis-cyber-

warriors_us_5750779ae4b0eb20fa0d2684?ir=Technology§ion=us_technology&utm_hp_ref=

technology.

27

to infect the wider population with an understanding of Islam that is tolerant and

non-violent—in part because the organization believes that its understanding of

Islam can serve as an exemplar for the Muslim world, and in part to prevent the

spread of extremism.

Supporting example: Russian interference in Brexit

Actor: Russian troll farms

Message: Pro-Brexit, Pro-leave

Target Population: British people

On June 23, 2016—the day of the Brexit vote—over “150,000 Russian-language

Twitter accounts posted tens of thousands of messages in English” advocating for a

leave vote in the referendum.

48

The campaign was relatively short-lived but still

robust. The implicated accounts had been mostly silent on the issue of Brexit in the

month leading up to the referendum, but became active as the vote approached. One

set of researchers found, for example, that the pace increased from “about 1,000 a

day two weeks before the vote to 45,000 in the last 48 hours.”

49

Another study found

that 38 accounts that Twitter had identified as Kremlin-linked had tweeted 400 times

on the day of the vote. A third analysis found that 29 of the Russian accounts

identified to Congress had “also tweeted 139 times about Britain or Europe.”

50

And a

fourth found that “a network of more than 13,000 suspected bots” tweeted pro-

Brexit messages.

51

Importantly, though, much of this early analysis focused on

Twitter accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency and so doesn’t necessarily

offer a comprehensive overview of Russian activity as the vote approached.

This campaign relied on a number of tactics. First, the Twitter accounts were linked

to a variety of profiles and “people purporting to be a U.S. Navy veteran, a Tennessee

Republican and a Texan patriot—all [tweeted] in favour of Brexit.”

52

The tweets

48

David D. Kirkpatrick, “Signs of Russian Meddling in Brexit Referendum,” New York Times,

November 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/15/world/europe/russia-brexit-

twitter-facebook.html.

49

Ibid.

50

Ibid.

51

James Ball, “A Suspected Network Of 13,000 Twitter Bots Pumped Out Pro-Brexit Messages In

The Run-Up To The EU Vote,” Buzzfeed, October 20, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/

jamesball/a-suspected-network-of-13000-twitter-bots-pumped-out-

pro?utm_term=.wwnGyBKKP#.iiBXNkMMY.

52

Robert Booth et al., “Russia Used Hundreds of Fake Accounts to Tweet About Brexit, Data

Shows,” Guardian, November 14, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/

nov/14/how-400-russia-run-fake-accounts-posted-bogus-brexit-tweets.

28

invoked hashtags such as #EUref, #BrexitInOut, #BritainInOut and #BrexitOrNot in

order to connect to a broader discourse.

53

In some instances, they deployed anti-

Muslim language and stoked fears about immigrants. As one analyst noted: “Many of

these accounts strongly pushed the narrative that all Muslims should be equated

with terrorists and made the case that Muslims should be banned from Europe.”

54

As

one example, a Twitter user tweeted: “I hope UK after #BrexitVote will start to clean

their land from muslim invasion!”

55

The account went on to post a widely shared

photo—captioned to deliver an anti-Islamic message—taken during the attack on the

Westminster Bridge.

56

This image can be seen in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Examples of responses to Russian interference in Brexit

Source:

See Footnote 55.

Importantly, the campaign wasn’t nearly as extensive as the similarly structured and

themed campaign to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election (discussed

below). Nor is it entirely clear what this campaign was attempting to accomplish. As

one analyst noted, “We cannot say whether [these accounts] were primarily trying to

influence Brexit or whether it was a side effect of them trying to wreak discord

53

Caroline Mortimer, “If You Saw These Tweets, You Were Targeted By Russian Brexit

Propaganda,” Independent, November 12, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-

style/gadgets-and-tech/news/brexit-russia-troll-factory-propaganda-fake-news-twitter-

facebook-a8050866.html.

54

David D. Kirkpatrick, “Signs of Russian Meddling in Brexit Referendum,” New York Times,

November 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/15/world/europe/russia-brexit-

twitter-facebook.html.

55

Robert Booth et al., “Russia Used Hundreds of Fake Accounts to Tweet About Brexit, Data

Shows,” Guardian, November 14, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/

nov/14/how-400-russia-run-fake-accounts-posted-bogus-brexit-tweets.

56

Ibid.

29

generally.”

57

The content was “quite chaotic” and perhaps “aimed at wider

disruption.”

58

And yet despite this ambiguity, it seems clear that these Kremlin-linked

accounts were aspiring to infect a portion of the population with a clearly pro-Brexit

message.

Supporting example: Russian interference in U.S.

presidential election

Actor: Russian troll farms

Message: Pro-Trump, Anti-Clinton, Pro-civil discord

Target Population: American people

In 2016, a series of Russian-linked social media accounts—primarily on Twitter and

Facebook, but also on YouTube, Tumblr, and Pokémon Go—shared a number of

memes designed to influence the outcome of the American election. The ultimate

goal of these Russian actors remains unclear. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

asserted that they aspired to aid then-candidate Trump, and the Federal Bureau of

Investigations (FBI) asserted that there was no firm evidence to support this

conclusion. Minimally, though, the activity seems to have been designed to disrupt

the American political process by infecting the public discourse. As Facebook itself

noted, the ads purchased on its website “appeared to focus on amplifying divisive

social and political messages across the ideological spectrum.”

59

An investigation into

the activity continues, and indictments accusing 13 individual Russian citizens of

interfering in the election came down in early 2018.

60

An example of some memes

that were used as part of this campaign are shown in Figure 16.

57

David D. Kirkpatrick, “Signs of Russian Meddling in Brexit Referendum,” New York Times,

November 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/15/world/europe/russia-brexit-

twitter-facebook.html.

58