CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE

Transferring Credit

Risk on Mortgages

Guaranteed by

Fannie Mae or

Freddie Mac

December 2017

GSE December 12, 2017 5:00 PM

i of i

© Trong Nguyen/Shutterstock.com

Notes

Unless this report indicates otherwise, all years referred to are federal scal years, which

run from October 1 to September 30 and are designated by the calendar year in which

they end.

Numbers in the text, tables, and gures may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Supplemental data are posted with this report on CBO’s website.

www.cbo.gov/publication/53380

Table

1. Interest Rate Spread Paid on the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes in 2018 8

Figures

1. Overview of the Structure of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes 5

2. Loss Coverage of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes Under Current Policy and Option 1 7

3. Risk Exposure on the GSEs’ 2018 Cohort of Guarantees Under

Current Policy and Option 1 13

4. Risk Exposure on the GSEs’ 2008–2012 Cohorts of Guarantees Under Option 2 14

5. Annual Net Premiums Collected on the GSEs’ 2018 Cohort of

Guarantees Under Current Policy and Option 1 16

6. Annual Net Premiums Collected on the GSEs’ 2008–2012 Cohorts of

Guarantees Under Option 2 18

Contents

Summary and Introduction 1

How Do the GSEs Share Risk With Private Investors? 1

How Are the GSEs’ Risk- Sharing TransactionsWorking? 1

How Could the GSEs Expand eir Risk Sharing? 2

Rationales for the GSEs’ Credit- Risk- TransferTransactions 2

The Current State of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk- TransferTransactions 3

Types of CRT Transactions 4

Amount of Risk Transferred 5

Options for Expanding the GSEs’ Credit- Risk- TransferTransactions 6

Option 1A: Transfer a Larger Share of the Currently Covered Losses 7

Option 1B: Transfer Losses Up To a Higher Percentage of the Unpaid Principal Balance 8

Option 2: Share Risk on Mortgages Guaranteed Between 2008 and 2012 9

Uncertainty About Pricing Under the Options 10

Eects of the Options for Expanding the GSEs’ Credit- Risk- Transfer Transactions 10

Eects on the Fair- Value Subsidy Cost of the GSEs 11

Eects on the GSEs’ Exposure to Risk 11

BOX 1. WAYS OF MEASURING THE GSE’ EXPOSURE TO CREDIT RISK 12

Eects on the GSEs’ Annual Net Premiums 15

About This Document 19

Transferring Credit Risk on Mortgages

Guaranteedby Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac

Summary and Introduction

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are government- sponsored

enterprises (GSEs) that help nance mortgages in the

United States. ey were originally established by the

federal government as private corporations with a public

mission. However, in September2008, the government

placed the GSEs in conservatorships under their reg-

ulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA),

because of nancial distress stemming from the recession

that began in 2007.

Today, under those conservatorships, the debt securities

and mortgage- backed securities (MBSs) that Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac issue are eectively guaranteed by

the federal government (subject to limits). at guaran-

tee explicitly exposes the government to risk from the

activities of the GSEs.

1

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac operate mainly in the sec-

ondary (or resale) market for single- family mortgages.

2

ey buy mortgages that meet certain standards from

banks and other mortgage originators; pool those loans

into mortgage- backed securities, which they guarantee

against most of the losses from defaults on the under-

lying mortgages; and sell the MBSs to investors—a

process known as securitization. e GSEs’ guarantees

1. For an overview of the federal government’s support of the GSEs,

see Congressional Budget Oce, e Eects of Increasing Fannie

Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s Capital (October2016), www.cbo.gov/

publication/52089.

2. e two GSEs also guarantee loans in the multifamily mortgage

market and invest in mortgage- related securities for their

portfolios of assets. ose investment portfolios expose the

GSEs to interest rate risk and prepayment risk—that is, to the

possibility of losses when uctuating interest rates and early

repayments of mortgages create a gap between the value of

the GSEs’ asset portfolios and the value of the debt securities

used to fund them. For more information about the GSEs’

operations, see Congressional Budget Oce, Fannie Mae, Freddie

Mac, and the Federal Role in the Secondary Mortgage Market

(December2010), www.cbo.gov/publication/21992.

on MBSs provide insurance to investors that they will

receive payments of principal and interest on the under-

lying mortgages even if a borrower defaults. Some of the

other losses from defaults on those mortgages are borne

by private mortgage insurers. However, on most of the

loans pooled into MBSs, the GSEs—and thus the federal

government—bear a signicant share of the risk of losses

as part of their traditional guarantee operations.

3

How Do the GSEs Share Risk With Private Investors?

At the direction of FHFA, the GSEs began undertaking

transactions in 2013 to transfer some of the credit risk

of their guarantees to private investors.

4

In most of those

transactions, the GSEs issue bonds, called credit- risk

notes, that pay principal and interest to investors based

on the performance of an underlying pool of mortgages

guaranteed as part of traditional MBSs. Credit- risk notes

insulate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from a specied

amount of mortgage losses by having those losses reduce

the amount of principal repaid to holders of the notes.

e GSEs have also experimented with reducing their

exposure to credit risk by issuing subordinate MBSs that

they do not guarantee, by having mortgage originators

retain some of the risk on the loans sold to the GSEs,

and by purchasing reinsurance on pools of mortgages.

How Are the GSEs’ Risk- Sharing

TransactionsWorking?

e Congressional Budget Oce examined how the

GSEs’ use of credit- risk- transfer (CRT) transactions has

3. In the case of mortgages issued to borrowers who made a

20percent down payment, the GSEs have historically insured

investors against all losses on those loans. In the case of mortgages

issued with less than a 20percent down payment, a private

mortgage insurer generally covers a portion of losses ahead of the

GSEs.

4. To date, those investors have consisted mainly of private- sector

money managers, hedge funds, insurance companies, and

real estate investment trusts. Public entities, such as foreign

governments or U.S. state and local governments, have not been

signicant investors in the market for the GSEs’ credit risk.

2 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

been operating under current policy and concluded the

following:

■ Current CRT transactions are being executed in a

fully functioning liquid market, and the GSEs use

a competitive process to determine the price they

will pay private investors to accept the risk being

transferred. Although those transactions generate

administrative expenses for the GSEs, they do not

change the GSEs’ fair- value subsidy cost.

5

(Fair value

is a market- based measure of the federal government’s

obligations and is the measure that CBO uses to

estimate the subsidy cost of Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac in the federal budget.)

■ Currently planned CRT transactions are projected to

reduce the GSEs’ exposure to risk by $2.8billion in

2018. at amount is equal to 11percent of the total

risk exposure from the GSEs’ new guarantees in that

year, CBO estimates. (In this analysis, CBO evaluates

risk exposure using a fair- value measure of losses from

defaults that implicitly puts more weight on losses

that occur in adverse economic conditions.)

■ If the economy performs as CBO projects in its

January 2017 baseline macroeconomic forecast, the

currently planned CRT transactions will reduce

the GSEs’ total net premium income on their

2018guarantees. e reason is that, under normal

economic conditions, the GSEs will pay more in

interest to CRT investors than they will receive

in protection from losses. e situation may be

dierent if the economy experiences more challenging

conditions, such as a severe recession. In that case, the

5. at conclusion follows directly from the denition of fair

value—which is the price paid in an orderly, competitive

market—and the exclusion of administrative costs from the fair-

value measure that CBO uses to estimate the subsidy cost of the

GSEs. (For a discussion of the accounting for administrative costs

in a fair- value estimate, see Congressional Budget Oce, Fair-

Value Accounting for Federal Credit Programs (March2012), p.10,

www.cbo.gov/publication/43027.) Transferring credit risk in

orderly transactions at market prices would not directly increase

or decrease the subsidy cost of the GSEs (dened as the dierence

between the present value of projected fair- value insurance losses

on mortgages guaranteed by the GSEs and the present value of

fair- value fees that the GSEs are projected to collect in exchange

for providing those guarantees). If markets were disorderly,

transfers might occur only at “re sale” prices that would be

below fair value, creating signicant costs on a fair- value basis.

e estimates of subsidy cost in this analysis are for transfers

conducted in orderly markets.

GSEs’ net premium income may be higher with CRT

transactions than it would be otherwise, meaning that

the GSEs will receive more in protection than they

will pay in interest. (Net premium income is dened

here as the GSEs’ collections of premiums for their

guarantees net of interest paid to the investors involved

in CRT transactions and net of losses borne by the

GSEs in excess of losses borne by CRT investors.)

How Could the GSEs Expand Their Risk Sharing?

CBO also analyzed two approaches for expanding the

GSEs’ eorts to share risk with investors: increasing the

amount of risk shared on new mortgages guaranteed in

the future, and transferring some of the risk on mort-

gages guaranteed before 2013, when the current CRT

program began. CBO concluded that expanding the

GSEs’ use of credit- risk transfers in those ways would

have the following eects:

■ Produce no change in the fair- value subsidy cost of

the GSEs;

■ Further reduce the GSEs’ risk exposure in 2018; and

■ Further reduce the total annual net premiums

collected by the GSEs on their guarantees, compared

with net premium income in the absence of risk

sharing, if the economy performs as CBO projects

in its baseline macroeconomic forecast, or further

increase net premium income (relative to not

conducting credit- risk transfers) under a scenario of

economic stress.

Rationales for the GSEs’

Credit- Risk- TransferTransactions

In 2013, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began sharing

with private investors a portion of the credit risk on

single- family mortgages they guarantee. ose credit-

risk- transfer transactions are designed to accomplish a

number of goals set out by the GSEs’ conservator and

regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

6

First, CRTs are designed to reduce the cost to taxpayers

from the risk of future losses associated with the GSEs’

credit guarantees. Under a traditional guarantee, if a

6. For a discussion of alternative ways to share credit risk with the

private sector, see Congressional Budget Oce, Transitioning

to Alternative Structures for Housing Finance (December2014),

www.cbo.gov/publication/49765.

3deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

borrower defaults on a mortgage backed by the GSEs,

they assume the costs of default that are not borne by

the borrower or a private mortgage insurer. CRT trans-

actions shift some of those costs from the GSEs to other

private parties, such as investors, mortgage insurers, or

private reinsurance rms.

Second, CRT transactions help to create a broader, more

liquid market for mortgage credit risk by introducing

multiple sources of private capital. (In a liquid market,

investors can quickly buy or sell large quantities of an

asset without aecting its price.) Before 2013, providers

of private capital participated in absorbing credit losses

on mortgages mainly through the market for private-

label securities (MBSs issued and insured by private

companies without government backing) and through

the private mortgage insurance industry.

7

Today, the

market for private- label securities is much smaller than

it was before the 2007–2009recession, but investors

can still assume mortgage credit risk by investing in the

credit- risk notes and other CRT instruments issued by

the GSEs. Ultimately, the market created through those

CRT transactions may aid in developing a private market

for mortgage credit risk after the GSEs’ conservator-

ships end by reducing the direct role of the GSEs in the

mortgage market.

ird, CRT transactions help to create transparency

about the price of mortgage credit risk by providing a

clear signal of the price that private investors would pay

to assume a share of the risk borne by Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac. e GSEs and others may use that price

signal to gauge the appropriate level at which to set the

fees they charge mortgage borrowers for their guarantees

in the future. Although the GSEs publish their guarantee

fees (both individually and through FHFA) and provide

some information about how those fees are determined,

the fact that the GSEs are explicitly backed by the

federal government gives them a nancing advantage

over private mortgage insurers. at advantage creates

an opportunity for the GSEs to price their mortgage

guarantees at below- market, subsidized levels. Allowing

private investors to buy and trade a share of the credit

risk currently borne by the GSEs increases transparency

about the value of the risk that the GSEs have assumed.

7. Providers of private capital bear credit risk on mortgages that

are not guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or the Federal

Housing Administration. at credit risk is borne mainly

by banks (which originate mortgages and hold them in their

portfolios) or by investors that purchase private- label securities.

CRT transactions are designed to shift risk, and thus

costs, away from the GSEs, but risk transfers also create

some concerns for the GSEs. For example, although

there may be a stable supply of investors willing to

assume credit risk from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

under normal market conditions, it could be dicult

to entice private investors to assume that risk during

periods of market stress. In that case, the GSEs might

be left holding a larger share of the risk of losses on their

traditional guarantees. In addition, some analysts argue

that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac pay more than a fair-

market price to transfer risk in some CRT transactions—

driven in part by FHFA’s goals for the amount of risk

it wants the GSEs to share—potentially weakening the

GSEs’ nancial positions.

8

Finally, although current CRT

transactions have been designed not to harm the liquid-

ity of the broader MBS market, a small potential exists

that carrying out a large volume of certain types of CRT

transactions, which make the underlying loans ineligible

for standard securitization, could reduce the liquidity of

that market. (Such transactions might include senior-

subordinate securities and mortgage- originator recourse

transactions, which are described below.)

The Current State of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk-

TransferTransactions

According to FHFA, between July2013 and

December2016, Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s CRT

transactions transferred a portion of the credit risk on a

total of $1.4trillion in mortgages, as measured by the

unpaid principal balance (UPB) of the loans when the

CRTs occurred.

9

ose mortgages represent a substantial

share of the new loans that the GSEs guaranteed during

that period. e GSEs’ objective in 2017 is to share risk

8. See J. Timothy Howard, “Risk Sharing, Or Not,” Howard on

Mortgage Finance (blog entry, March9, 2016), http://tinyurl.

com/y7wwmkka. Assessing the degree to which current market

prices for the GSEs’ risk- sharing transactions reect the future

costs of the GSEs’ guarantee operations is uncertain and subject

to dierences in modeling assumptions and methods. For

example, FHFA analyzed certain issuances of credit- risk notes by

the GSEs and concluded that the market- based credit costs in

those deals implied an estimated guarantee fee below the actual

fee that the GSEs charged on the related mortgages—suggesting

that the GSEs paid less than a fair- market price to transfer

risk in some CRT transactions. See Federal Housing Finance

Agency, Credit Risk Transfer Progress Report: December2016

(March2017), http://tinyurl.com/y7cqlp6e.

9. See Federal Housing Finance Agency, Credit Risk Transfer Progress

Report: December2016 (March2017), http://tinyurl.com/

y7cqlp6e.

4 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

on at least 90percent of the total UPB of the newly

guaranteed loans it is targeting for credit- risk transfers.

e portion of credit risk shared on those loans depends

on the measure used to dene risk. e GSEs’ current

CRT transactions leave investors with a large share of

expected losses—that is, losses from the defaults pro-

jected to occur if the economy performs as CBO projects

in its baseline macroeconomic forecast. Under measures

of risk that include losses from the defaults that might

occur if the economy experienced more challenging

conditions, the GSEs’ current CRT transactions transfer

a smaller share of losses to private investors.

Types of CRT Transactions

To date, the GSEs have used several kinds of transactions

to transfer credit risk. e most common type of trans-

action is the issuing of credit- risk notes, which account

for 78percent of the dollar amount of CRT instruments

sold to investors. ose notes—called Structured Agency

Credit Risk (STACR) at Freddie Mac and Connecticut

Avenue Securities (CAS) at Fannie Mae—are bonds that

pay principal and interest to investors based on the per-

formance of an underlying pool of mortgages guaranteed

as part of traditional MBSs. e underlying loans are

known as the reference pool.

e principal balance of the credit- risk notes is a per-

centage of the total outstanding balance of the reference

pool.

10

at outstanding balance is divided into dier-

ent bonds, called tranches, that have diering levels of

seniority (see Figure 1). A fraction of borrowers’ sched-

uled and unscheduled principal payments on mortgages

in the reference pool is used to repay the most senior

tranche still outstanding at any given point. ose

payments are made on a prorated basis: For example, if

the principal balance of the credit- risk notes at issuance

represented 1percent of the principal balance of the

reference pool, 1percent of principal payments on the

reference loans is used to repay the holders of the most

senior tranche. By contrast, all losses on mortgages in the

reference pool are used to reduce the principal balance of

the most subordinate tranche outstanding. For instance,

$1of losses on the reference pool reduces the principal

10. e fact that the GSEs receive the principal balance of the notes

from investors eliminates counterparty risk, the possibility that

lenders or investors with whom the GSEs share risk will not

honor their obligations.

balance of the most subordinate tranche outstanding

by$1.

11

e GSEs pay interest to investors on the unpaid princi-

pal of the credit- risk notes. e interest rate is a oating

rate—a specic percentage (or spread) above the London

Interbank Oer Rate (LIBOR) that varies by tranche.

For the GSEs’ recent issuances of credit- risk notes, aver-

age spreads have ranged from approximately 1percent-

age point for the most senior tranche to 10percentage

points for the most subordinate tranche. ose spreads

are generally set to ensure that the bonds sell to investors

at par, meaning that investors pay $1 for every $1 of

principal of the credit- risk note.

e spread for each tranche is based on private investors’

assessment of the risks inherent in that tranche, includ-

ing credit risk, liquidity risk, and market risk. Tranches

that are more exposed to the risk of credit losses on loans

in the reference pool have a higher spread to compensate

investors for the potential loss of principal. (Although

losses are less likely on more senior tranches, those

tranches are exposed to the risk that borrowers will repay

their mortgage principal early.) All tranches provide

investors with compensation for liquidity risk, the risk

that investors may receive less money if they attempt to

sell their tranches before maturity (because the market

for credit- risk notes is much smaller than the market for

MBSs issued by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac). e spread

also includes compensation for the cost of market risk,

the risk that investors face because losses on guaranteed

mortgages tend to be high when economic and nancial

conditions are poor and resources are therefore more

valuable.

12

Besides issuing credit- risk notes, Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac have used several other types of transactions, on a

smaller scale, to transfer risk:

11. For more information about how the STACR and CAS

programs operate, see Freddie Mac, “Freddie Mac Structured

Agency Credit Risk (STACR®)” (accessed October23, 2017),

www.freddiemac.com/creditriskoerings/stacr_debt.html; and

Fannie Mae, “Connecticut Avenue Securities (CAS)” (accessed

October23, 2017), http://tinyurl.com/hursvq6.

12. Market risk is the component of nancial risk that remains

even after investors have diversied their portfolios as much as

possible. It results from shifts in macroeconomic conditions,

such as productivity and employment, and from changes in

expectations about future macroeconomic conditions.

5deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

■ Senior- subordinate securities—securities that the

GSEs issue outside the traditional MBS market that

consist of a senior bond shielded from credit losses

by a subordinate bond, which does not have a GSE

guarantee;

■ Mortgage- originator recourse transactions and “front-

end” pilots—arrangements in which lenders keep a

portion of the credit risk on mortgages they sell to the

GSEs, often by agreeing to repurchase certain loans

that default in exchange for paying the GSEs a lower

guarantee fee (which can exclude those loans from the

traditional MBS market); and

■ Pool- level reinsurance—supplementary insurance

that the GSEs purchase from a traditional mortgage

insurer or reinsurance rm to cover losses on a pool

of loans that exceed the coverage provided by the

primary mortgage insurance that the individual loans

carry.

13

13. See Federal Housing Finance Agency, Single- Family Credit

Risk Transfer Progress Report (June2016), http://tinyurl.com/

yc6kgda2.

Amount of Risk Transferred

Although the GSEs have transferred risk on mortgages

with a total UPB of more than $1.4trillion, the maxi-

mum amount of credit risk that private investors bear on

those loans is much smaller than that unpaid principal

balance. Investors cover only an amount of loss repre-

sented by their bond investment (for credit- risk notes

and senior- subordinate securities), their recourse arrange-

ment, or their insurance obligation (for reinsurance). For

example, the STACR and CAS notes sold to investors

through December2016covered slightly more than

$38billion of losses on mortgages with a total UPB of

$1.2trillion.

e GSEs’ recent issuances of credit- risk notes cover

losses of about 3.75percent of the original UPB of the

underlying mortgages, on average. However, only notes

covering an average of about 3percent of the original

UPB were sold to private investors. e GSEs typically

retain a small portion of the more senior tranches and

a large portion of the subordinate tranches instead of

selling them to investors. e GSEs keep some of those

credit- risk notes for a variety of reasons, including to

Figure 1 .

Overview of the Structure of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes

Mortgage Borrowers’ Scheduled and Unscheduled

Principal Payments Are Used to Repay the Most Senior

Tranche Outstanding

Total Outstanding Balance of the Reference

Pool Is Divided Into Dierent Tranches of

Credit-Risk Notes, Which Have Diering

Levels of Seniority

Losses From Defaults Are Used to Reduce the Principal

Balance of the Most Subordinate Tranche Outstanding

Tranche 1

Tranche 4

Tranche 3

Tranche 2

Reference

Pool of Mortgages

Guaranteed

by the GSEs

Senior

Subordinate

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

GSEs = government- sponsored enterprises (in this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

6 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

show that their interests are aligned with those of inves-

tors and, in the case of subordinate tranches, because

they judge that the economic value of holding that risk

outweighs the value of selling it at current market prices.

e 3.75percent average loss coverage on credit- risk

notes issued recently would have been sucient to

cover most of the losses that the GSEs experienced on

their guarantees during the height of the most recent

crisis in the mortgage market, which began in calendar

year 2007. For example, according to a 2015report by

FHFA, Freddie Mac’s losses reached roughly 3.5per-

cent on mortgages guaranteed in calendar year 2007—a

cohort of loans whose borrowers had a lower average

credit score than loans guaranteed by the GSEs since

the housing crisis.

14

At the time of the FHFA report,

nearly 20percent of the 2007cohort of loans remained

outstanding, so losses on that cohort could increase, but

total losses are likely to remain below 5percent of the

initial loan balance. As a result, FHFA and the GSEs

assert that STACR and CAS transactions generally insu-

late the GSEs from all but “catastrophic” losses. Another

means of assessing the risk on single- family mortgages

is bank capital standards. Such standards require banks

holding single- family mortgages similar to those guaran-

teed by the GSEs to retain at least 4percent of the loan

balance as capital.

15

In its latest annual report setting objectives for Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac, FHFA called on the GSEs to

transfer a “meaningful” amount of credit risk on at least

90percent of the UPB of newly guaranteed loans that

meet certain criteria in 2017. Specically, the GSEs’

target is to share risk on 90percent of the UPB of the

following types of mortgages: renance loans (other than

those from the Home Aordable Renance Program or

those with high loan- to- value ratios), xed- rate mort-

gages with terms longer than 20years, and mortgages

with loan- to- value ratios greater than 60percent.

16

14. See Federal Housing Finance Agency, Overview of Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac Credit Risk Transfer Transactions (August2015),

http://tinyurl.com/ydbzm5gq.

15. For a description of capital requirements for mortgage- related

assets, see Government Accountability Oce, Mortgage-

Related Assets: Capital Requirements Vary Depending on Type of

Asset, GAO- 17- 93 (December2016), www.gao.gov/products/

GAO- 17- 93.

16. See Federal Housing Finance Agency, 2017Scorecard for

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Common Securitization Solutions

(December2016), http://tinyurl.com/y9qzho6b.

FHFA also directed the GSEs to continue to experiment

with new risk- sharing structures and partners.

Options for Expanding the GSEs’

Credit- Risk- TransferTransactions

Although Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac already transfer

some risk on most of the new mortgages they guaran-

tee, the GSEs could expand their risk- sharing eorts

to promote additional private- sector participation. e

ultimate goals of such an expansion would be to reduce

taxpayers’ exposure to the risk of losses on those guaran-

tees and to make loan costs for mortgage borrowers more

competitively determined and transparent.

CBO forecasts the credit- risk transfers that Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac will conduct in future years as part

of its baseline projections of the budgetary eects of

federal programs that guarantee mortgages.

17

On the

basis of the GSEs’ current policy, CBO estimates that for

loans newly guaranteed in 2018, the GSEs will trans-

fer a portion of risk on 70percent of those mortgages

overall and on 90percent of the subset of mortgages

targeted for risk sharing. CBO projects that the GSEs

will sell credit-risk notes covering 20percent of the losses

equal to the rst 0.5percent of the original UPB of the

reference pool of loans and 85percent of the losses that

equal between 0.5percent and 3.75percent of the pool’s

original UPB (see Figure 2).

18

In other words, if a refer-

ence pool of GSE- guaranteed mortgages had an original

unpaid principal balance of $1million in all, the GSEs

would sell credit- risk notes covering 20percent of the

rst $5,000in losses on that pool (covering $1,000in

losses) and 85percent of the losses between $5,000

and $37,500 (covering up to an additional $27,625in

losses).

17. e projections in this report are based on the budget

and macroeconomic projections that CBO published in

January2017in e Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027

(www.cbo.gov/publication/52370). In that baseline, Fannie

Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s total volume of loan guarantees in 2018

is projected to be $935billion. In June2017, CBO released

updated projections in An Update to the Budget and Economic

Outlook: 2017 to 2027 (www.cbo.gov/publication/52801). In

that update, the GSEs’ total volume of loan guarantees in 2018

is projected to be $818billion. e conclusions of this report

would be generally unchanged using either forecast.

18. With notes issued in calendar year 2017, the GSEs have retained

a larger share of the losses equal to the rst 0.5percent of the

original UPB of the reference pool, including many issuances

in which they sold no credit- risk notes covering those losses.

However, CBO estimates that they will sell notes covering

20percent of such losses in 2018.

7deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

Under that current policy, the GSEs will engage in a

total of $18.6billion in CRT transactions with investors

in 2018, CBO estimates. (Although the GSEs conduct

various types of risk- sharing arrangements with dier-

ing characteristics, CBO assumes for simplicity’s sake

that all CRT transactions executed in 2018 and beyond

involve credit- risk notes.)

e GSEs could increase the amount of risk they share

with investors on newly guaranteed mortgages by selling

notes that cover a larger share of the losses equal to the

rst 3.75percent of the reference pool’s unpaid princi-

pal balance or by selling notes that cover losses up to a

higher percentage of the pool’s UPB. e GSEs could

also expand the CRT program to include mortgages

guaranteed before 2013, when the program began.

CBO examined several illustrative versions of those

approaches.

Option 1A: Transfer a Larger Share of the Currently

Covered Losses

In the rst alternative that CBO analyzed, for loans

newly guaranteed in 2018, the GSEs would transfer

40percent (rather than 20percent) of the losses equal

to the rst 0.5percent of the original unpaid principal

balance of the reference pool of loans and 95percent

(rather than 85percent) of the losses that equal between

0.5percent and 3.75percent of the pool’s original UPB

(see Figure 2). CBO estimates that the GSEs could

sell credit- risk notes covering that larger share of losses

for the same interest rate spread over the one- month

LIBOR as on their existing notes sold to investors (see

Table 1). Under this alternative, the GSEs would sell

$21.4billion (rather than $18.6billion) in credit- risk

notes to investors in 2018, CBO estimates, covering the

same pool of mortgages as under current policy.

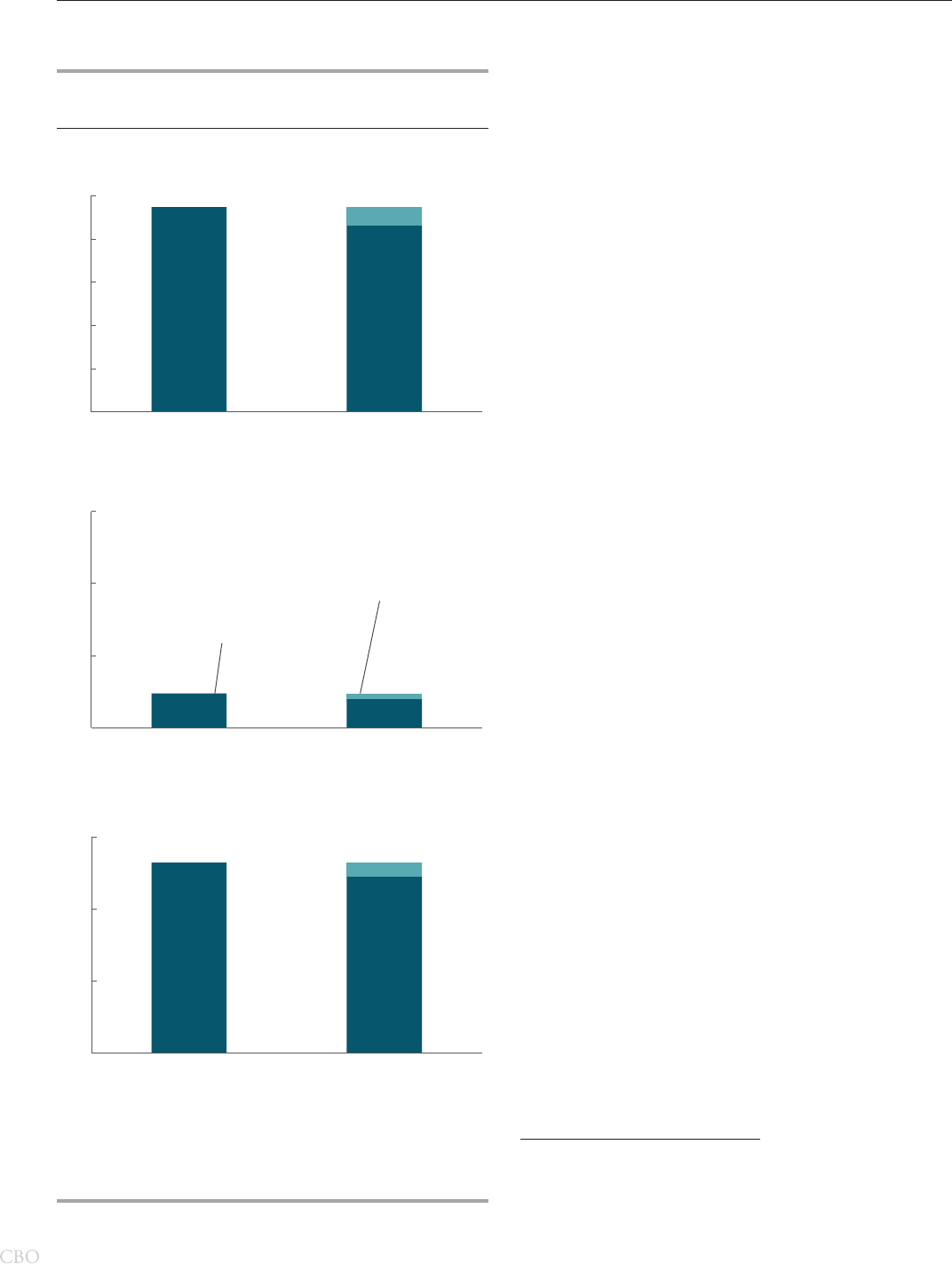

Figure 2 .

Loss Coverage of the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes Under Current Policy and Option 1

Losses as a Percentage of the Original UPB of the Reference Pool

Under GSEs’ Current Policy of

Credit-Risk Transfers

Option 1A (GSEs Transfer

a Larger Share of the

Currently Covered Losses)

Option 1B (GSEs Transfer

Losses Up To a Higher

Percentage of the UPB)

0

0.5

3.75

0

0.5

3.75 3.75

0

0.5

1.0 1.0

1.0

2.55 2.55

2.55

6.0

85%

85%

85%

85%

95%

95%

95%

Losses Covered by Credit-Risk

Notes Sold to Investors

Losses Retained

by the GSEs

85%

85%

85%

20% 40%

20%

Share of Losses Share of Losses Share of Losses

Tranche 1

Tranche 0

Tranche 4

Tranche 3

Tranche 2

Tranche 1

Tranche 4

Tranche 3

Tranche 2

Tranche 1

Tranche 4

Tranche 3

Tranche 2

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

In the case of current policy, CBO estimates that in 2018, the GSEs will sell credit- risk notes covering 20 percent of the losses equal to the first 0.5

percent of the original UPB of the reference pool of loans and 85 percent of the losses that equal between 0.5 percent and 3.75 percent of the pool’s

original UPB. In other words, if a reference pool of GSE- guaranteed mortgages had an original UPB of $1 million in all, the GSEs would sell credit- risk

notes covering 20 percent of the first $5,000 in losses on that pool (covering $1,000 in losses) and 85 percent of the losses between $5,000 and

$37,500 (covering up to an additional $27,625 in losses). Options 1A and 1B would modify those percentages as shown here.

GSEs = government- sponsored enterprises (in this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac); UPB = unpaid principal balance.

8 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

Option 1B: Transfer Losses Up To a Higher

Percentage of the Unpaid Principal Balance

In another version of this approach that CBO analyzed,

the GSEs would issue credit- risk notes covering a portion

of the losses equal to as much as 6percent of the original

UPB of the reference pool of loans newly guaranteed in

2018.

19

e CRT program’s current average loss cover-

age, 3.75percent of the UPB, is generally considered

sucient to shield the GSEs from the losses on any

19. e GSEs issued credit- risk notes with loss coverage of up to

6.5percent in calendar years 2014 and 2015. In addition, many

notes issued in 2017have loss coverage of 4percent or more.

However, CBO’s baseline projections are based on the average

loss coverage of notes issued in calendar years 2016 and 2017,

which is closer to 3.75percent.

cohort of loans they guaranteed during the housing cri-

sis. However, although annual losses have not exceeded

5percent on average, CBO estimates that certain high-

risk categories of loans have experienced losses greater

than 5percent. (Such high- risk loans represent a smaller

share of the GSEs’ guarantees now than they did during

the crisis.) In addition, losses could exceed 5percent on

future years’ cohorts of guarantees if the GSEs loosened

their standards for issuing a guarantee or if the mortgage

market experienced stresses greater than those of 2007

and 2008.

Under this option, as under current policy, the GSEs

would transfer 20percent of the losses equal to the

rst 0.5percent of the reference pool’s original UPB.

Table 1 .

Interest Rate Spread Paid on the GSEs’ Credit- Risk Notes in 2018

Percentage Points Above the London Interbank Oer Rate

2018 Cohort of Guarantees

Spread Under Option2

(GSEs Share Risk on

Mortgages Guaranteed

Between 2008 and 2012)

Losses Covered

(Percentage of the

original UPB of the

reference pool)

Spread

Under GSEs’

Current Policy

of Credit- Risk

Transfers

Spread

Under Option 1A

(GSEs Transfer

a Larger Share

of the Currently

Covered Losses)

Spread

Under Option 1B

(GSEs Transfer

Losses Up To a

Higher Percentage

of the UPB)

2008

Cohort of

Guarantees

2012

Cohort of

Guarantees

Tranche 0 (Most senior

under Option 1B) 3.75 to 6.0 n.a. n.a. 1.0 n.a. n.a.

Tranche 1 (Most senior,

except under Option 1B) 2.55 to 3.75 1.2 1.2 1.3 2.3 0.7

Tranche 2 1.0 to 2.55 3.1 3.1 3.4 6.3 1.9

Tranche 3 0.5 to 1.0 4.9 4.9 4.9 9.8 2.9

Tranche 4 (Most subordinate) 0 to 0.5 10.3 10.3 10.3 20.5 6.2

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

The total outstanding balance of the reference pool of mortgages underlying credit- risk notes is divided into dierent bonds, called tranches, that have

diering levels of seniority. Borrowers’ scheduled and unscheduled principal payments on mortgages in the reference pool are used to repay the most

senior tranche still outstanding at any given point, whereas losses on mortgages in the reference pool are used to reduce the principal balance of the

most subordinate tranche outstanding. That dierence in risk accounts for the dierent interest rate spreads paid on dierent tranches.

Tranches 1 and 2 would bear the same losses under Option 1B as they would under current policy. CBO estimates that investors would require a

slightly higher spread for those tranches under Option 1B, however, because the tranches would be exposed to a greater risk of losses than those

same tranches under current policy. The reason is that under Option 1B, the most senior tranche would absorb more payments of reference loans

ahead of subordinate tranches. CBO estimates that investors would require identical spreads for tranches 3 and 4 under Option 1B and under current

policy because in both cases, those tranches would be exposed to similar levels of liquidity risk, market risk, risk of losses, and risk that borrowers will

repay their mortgage principal early.

GSEs = government- sponsored enterprises (in this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac); UPB = unpaid principal balance; n.a. = not applicable.

9deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

However, they would also transfer 85percent of the losses

that equal between 0.5percent and 6percent (rather

than 3.75percent) of the pool’s UPB (see Figure 2 on

page 7). Under this alternative, the GSEs would sell

$31.1billion (rather than $18.6billion) in credit- risk

notes to investors in 2018, CBO estimates, covering the

same pool of mortgages as under current policy.

Adding a senior tranche to cover losses between 3.75per-

cent and 6percent of the reference pool’s UPB would

extend the length of time in which credit- risk notes

would cover losses, because that senior tranche would

absorb more repayments of reference loans ahead of sub-

ordinate tranches. at additional time would allow the

notes sold to investors to cover more losses between zero

and 3.75percent of the UPB.

For example, under current policy, the most senior

tranche of a credit- risk note bears losses between

2.55percent and 3.75percent of the reference pool’s

original UPB (with subordinate tranches bearing losses

between zero and 2.55percent). at senior tranche also

receives the credit- risk note’s initial prorated share of bor-

rowers’ scheduled and unscheduled principal payments

on the loans in the reference pool. If those payments

were sucient to repay the entire tranche within two

years of its issuance and then losses exceeded 2.55per-

cent of the reference pool’s original UPB in the third

year, the GSEs would receive no protection from the

credit- risk note under current policy. Under this option,

by contrast, losses between 2.55percent and 3.75per-

cent of the UPB would be borne by the second- most

senior tranche, and the most senior tranche would cover

losses between 3.75percent and 6percent. at senior

tranche would also receive the credit- risk note’s initial

prorated share of borrowers’ principal payments on the

reference pool. If those payments were sucient to repay

the entire senior tranche within two years of its issuance

and then losses exceeded 2.55percent of the UPB in the

third year, the GSEs would receive protection from the

second- most senior tranche of the credit- risk note under

this option.

CBO estimates that investors buying those notes would

require spreads consistent with the ones oered under

current policy for similar risks (see Table 1). ose

spreads would range from about 10percentage points

above the one- month LIBOR to bear losses up to the

rst 0.5percent of the UPB to 1percentage point above

the one- month LIBOR to bear losses between 3.75per-

cent and 6percent of the UPB.

Option 2: Share Risk on Mortgages Guaranteed

Between 2008 and 2012

CBO also analyzed an option in which the GSEs would

expand their risk- sharing eorts to include loans origi-

nated before the 2013start of the CRT program. Such

older loans can be responsible for disproportionate

losses. For example, Fannie Mae reported last year that

mortgages originated between calendar years 2005 and

2008made up only 9percent of its outstanding guar-

antees but accounted for nearly 65percent of the total

credit losses on those guarantees.

20

e percentage of

losses from cohorts of mortgages guaranteed before 2013

is declining over time, but the GSEs could still share a

signicant fraction of future losses by entering into risk-

sharing agreements that cover pools of those older loans.

In CBO’s illustrative version of that approach, the GSEs

would share the losses expected to be incurred in 2018

and later years on loans originated from 2008 through

2012that were being paid on schedule by the borrowers

in 2018.

21

at risk sharing would take the same form

as recent issuances of credit- risk notes: e GSEs would

transfer 20percent of the losses equal to the rst 0.5per-

cent of the original UPB of the reference pool of loans

and 85percent of the losses that equal between 0.5per-

cent and 3.75percent of the pool’s original UPB. Under

this option, CBO estimates, the GSEs would sell inves-

tors $12.9billion in credit- risk notes based on reference

pools of outstanding mortgages originated each year

between 2008 and 2012.

e pricing of CRT transactions involving older loans

would provide additional transparency about the costs

of those loans. Such prices would not be relevant to the

pricing of new loans, however, because the prices paid

on notes linked to older loans would reect any deteri-

oration or improvement in the condition of those loans

20. See Fannie Mae, 2016ird Quarter Credit Supplement

(November2016), p.17, http://tinyurl.com/y8qcknsq

(PDF,2.3MB).

21. is option does not include mortgages originated in 2005,

2006, or 2007because few of those loans are still outstanding

(most having been repaid, for example, when the borrower

renanced the loan or sold the property). e option also

excludes loans from the 2008–2012period that will have been

repaid or gone into default before 2018or that are projected to

be delinquent in 2018.

10 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

since they were originated. For example, CBO estimates

that investors would require more compensation—in

the form of higher spreads—for credit- risk notes based

on the GSEs’ 2008cohort of guarantees than for notes

based on the 2018cohort because loans guaranteed

in 2008 are expected to have higher losses than loans

guaranteed in 2018 (see Table 1). Conversely, inves-

tors would require lower spreads for credit- risk notes

based on the 2012cohort than for notes based on the

2018cohort because losses are expected to be lower on

the remaining loans from the 2012cohort than on the

2018cohort, CBO estimates.

Uncertainty About Pricing Under the Options

e GSEs’ current credit- risk notes provide some

information about what private investors might charge

to share risk beyond the current parameters of the CRT

program. Nevertheless, the prices that the GSEs would

have to pay to expand their risk sharing are uncertain for

several reasons.

First, the private market may be more or less willing to

assume risk on loans originated during the housing crisis,

or to assume greater risk on newly originated loans, than

CBO projects. In that case, investors would require lower

or higher compensation than the estimates shown in

Table 1.

Second, given the potential that investors’ willingness to

accept that new risk may be higher or lower, the market

for credit- risk notes issued under the options might be

more or less liquid than CBO anticipates, further chang-

ing costs. Although that new risk might be more dicult

to price initially, developing structures that enabled the

GSEs to share additional risk could enhance the benets

of the existing CRT program for both the primary and

secondary mortgage markets.

Eects of the Options for Expanding the

GSEs’ Credit- Risk- Transfer Transactions

Risk- sharing transactions are designed to reduce the

credit losses borne by taxpayers, but the impact of those

transactions on the federal government and the budget

depends on a number of factors. First, measures of that

impact must take into account the price that Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac pay to compensate investors to accept

credit risk. As such, the full cost of the GSEs’ credit- risk

transfers is net of the reduction in credit losses and the

compensation paid to the investors assuming that risk.

Second, the estimated impact of CRT transactions

depends on the budgetary approach used to mea-

sure cost. CBO and the Administration use dierent

approaches to account for the activities of Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac in the federal budget, and they would

therefore have dierent estimates of the cost of the

GSEs’ risk- sharing transactions. CBO shows as federal

outlays the estimated present value of the GSEs’ new

credit activity.

22

ose estimates are constructed on a

fair- value basis that reects the cost of market risk. e

Administration, by contrast, reports in the budget the

GSEs’ annual cash transactions with the Treasury, which

now consist mainly of dividend payments to the Treasury

on stock purchased from the GSEs. CBO believes that its

approach more appropriately reects the GSEs’ current

relationship with the government and provides more

relevant and comprehensive information to policymakers

than the Administration’s approach does.

Finally, the cost of the GSEs’ activities is shown in

CBO’s baseline budget projections as a single estimate,

reecting the price a private investor would charge to

assume the GSEs’ guarantee obligations. at single

estimate represents the central estimate from a distribu-

tion of economic forecasts surrounding CBO’s baseline

macroeconomic forecast. However, policymakers may

also be interested in how CRT transactions aect the

GSEs under dierent economic conditions. us, in this

analysis, CBO examined the impact of the options under

a scenario of severe economic stress as well as under its

baseline macroeconomic forecast.

CBO analyzed how the options would aect the fair-

value subsidy cost of the GSEs (the dierence between

the present value of projected losses from defaults on

loans guaranteed by the GSEs and the present value

of the fees that the GSEs are projected to collect in

exchange for providing those guarantees), their exposure

to credit risk, and their annual net premiums. CBO

concluded that the options would have no eect on the

federal subsidy cost of the GSEs, as measured on a fair-

value basis; would increase the amount of risk transferred

22. A present value is a single number that expresses a ow of income

or payments in terms of an equivalent lump sum received or

paid today. For budget projections, such as those published

in e Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO chooses to report

cash transactions between the GSEs and the Treasury for the

current year instead of the fair- value estimate for that year. at

treatment helps align CBO’s decit estimates for the current scal

year with those of the Administration.

11deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

to investors; and, in some cases, would increase the

annual premiums collected by the GSEs, net of losses

and interest payments to CRT investors.

Eects on the Fair- Value Subsidy Cost of the GSEs

Each CRT transaction that the GSEs undertake with

a private entity is, by denition, conducted at market

prices. Market- priced transactions have a fair- value

subsidy rate of zero because the GSEs receive a fair-

value reduction in their credit losses in exchange for

making fair- value payments to investors. As a result,

those transactions do not directly increase or decrease

CBO’s estimate of the subsidy cost of the GSEs. CBO’s

January2017baseline, for example, projects a total

subsidy cost for the GSEs in 2018 of $1.7billion, taking

into account their current policy of credit- risk transfers.

23

If the GSEs implemented any of the options analyzed

in this report, that estimated subsidy cost would not

change.

e additional transactions carried out under those

options, however, would generate administrative

expenses, which are not included in CBO’s estimates

of the GSEs’ fair- value subsidy cost. For example, the

GSEs would pay rms for their assistance in selling

credit- risk notes to private investors. ose payments,

which are typically disclosed in the prospectus document

associated with the notes, reduced the proceeds that the

GSEs received for credit- risk notes sold in calendar year

2016by 0.25percent to 0.5percent of the principal

amount of the notes. With $13billion in credit- risk

notes sold in that year, the GSEs incurred about $40mil-

lion in payments, CBO estimates. Such administrative

expenses would not exist if the GSEs retained the credit

risk on the loans in the reference pool.

Eects on the GSEs’ Exposure to Risk

ere are many ways to measure the GSEs’ exposure to

the risk of credit losses, all of which capture aspects of

the distribution of potential losses. e measure that

CBO uses in this analysis is the insurance- loss compo-

nent of a fair- value estimate of the budgetary cost of the

GSEs’ guarantee operations. at measure accounts for

the market risk inherent in mortgage guarantees and thus

puts more weight on losses that occur in adverse eco-

nomic conditions. (For more details about that and other

measures of risk exposure, see Box 1.)

23. See Congressional Budget Oce, “Federal Programs at

Guarantee Mortgages” (January2017), www.cbo.gov/about/

products/baseline-projections-selected-programs#5.

Amount of Risk Transferred Under Current

Policy. CBO’s January2017baseline projects that the

GSEs will guarantee $935billion in newly originated

mortgages in 2018. Over their lifetime, those loans are

estimated to produce $25.3billion in insurance losses for

the GSEs on a fair- value basis (with market risk taken

into account). Of the $935billion in guaranteed loans,

about $732billion consists of loans that are projected to

potentially meet the GSEs’ target for CRT transactions.

CBO projects that the GSEs will issue credit- risk notes

on a reference pool of about $658billion—90percent

of the total amount of targeted loans, consistent with

FHFA’s goals, or about 70percent of the 2018cohort of

guarantees. e GSEs’ insurance losses on that reference

pool are projected to total about $17.7billion on a fair-

value basis.

CBO estimates that the market value of the risk trans-

ferred through those credit- risk notes will equal the

present value of the expected interest payments on the

notes.

24

Under their current CRT policy, the GSEs

will sell $18.6billion in credit- risk notes to investors

in 2018, CBO estimates, representing about 3percent

of the $658billion UPB of the reference pool. ose

transactions are expected to transfer approximately

$2.8billion in risk exposure to private investors—equal

to 11percent of the $25.3billion in expected fair-

value losses on the GSEs’ 2018cohort of guarantees, or

16percent of the $17.7billion in expected fair- value

losses on the reference pool (see Figure 3).

Reasons at the GSEs Would Retain Most of the Risk

of Losses. Despite those risk- sharing transactions, the

GSEs would still bear 89percent of the risk exposure on

their 2018cohort of guarantees under current policy.

In CBO’s assessment, there are three main reasons for

that result. First, about 30percent of the loans in the

2018cohort are not expected to meet the GSEs’ target

24. CBO’s estimate of the market value of the transferred risk

reects the entire interest rate that the GSEs pay to investors

and does not attempt to break down that rate into investors’

compensation for credit risk, market risk, and liquidity risk.

For arguments in favor of including liquidity risk in the

accounting for federal credit programs, see Financial Economists

Roundtable, Accounting for the Cost of Government Credit

Assistance (October2012), www.nancialeconomistsroundtable.

com. For arguments against including that risk, see Government

Accountability Oce, Credit Reform: Current Method to Estimate

Credit Subsidy Costs Is More Appropriate for Budget Estimates an

a Fair Value Approach, GAO- 16- 41 (January2016), p.51,

www.gao.gov/products/GAO- 16- 41.

12 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

Box 1.

Ways of Measuring the GSEs’ Exposure to Credit Risk

The cost of Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s guarantees of

single- family mortgages could be higher or lower than initially

projected because of unexpected changes in the risky cash

flows of the guarantees. Like other mortgage insurers, those

government- sponsored enterprises (GSEs) are exposed to the

risk of higher- than- expected losses mainly because of credit

risk, which stems from their obligation to repay the mortgage

holder when a borrower defaults. The credit risk of a loan—one

of the most significant risks posed by investments in mort-

gages—results from the possibility of unanticipated changes

in the likelihood and severity of losses from a default by the

borrower.

1

The GSEs’ exposure to credit risk can be measured in many

ways, all of which ultimately attempt to capture aspects of

the distribution of potential losses.

2

Those ways of measuring

include stress tests, the present value of expected insurance

losses, and the insurance- loss component of a fair- value esti-

mate of the GSEs’ cost.

In theory, potential losses on the GSEs guarantees range from

zero (no GSE- insured loan defaults) to 100 percent (all GSE-

insured loans default, and Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac recovers

nothing on any of them). However, even under the most

adverse market conditions, the GSEs’ ultimate risk exposure

is less than 100 percent of the unpaid principal balance of

their insured mortgages. The reason is that the GSEs typically

recover a portion of default costs through loss- mitigation

eorts (such as temporarily lowering borrowers’ payments

and oering flexible refinancing programs) or through sales of

foreclosed property.

1. The GSEs are also exposed, to a lesser extent, to other types of risks

inherent in the mortgage market. They include prepayment risk (the

possibility that interest rates will fall, prompting more borrowers than

expected to prepay their mortgages, thus reducing the GSEs’ premium

income), interest rate risk (the possibility that interest rates will dier from

the discount rate used to calculate the present value of the GSEs’ future

premiums), and counterparty risk (the possibility that the institutions that

service GSE- insured loans will not make premium payments to the GSEs in a

timely manner or that lenders will not honor their obligations).

2. For a discussion of the dierent approaches to measuring risk exposure,

see Congressional Budget Oce, Options to Manage FHA’s Exposure to

Risk From Guaranteeing Single- Family Mortgages (September 2017),

www.cbo.gov/publication/53084.

Stress Tests

An increasingly common approach to measuring risk exposure

is to use stress tests, simulations that provide estimates of

losses under adverse economic conditions. From the perspec-

tive of federal budgeting, stress- test scenarios tied to adverse

economic conditions have the desirable trait of drawing atten-

tion to outcomes that can occur when the pressure on federal

spending and revenues is likely to be greatest. But a limitation

of stress tests is that they depend on specific economic sce-

narios that provide little guidance about the likelihood of the

estimated losses.

Present Value of Expected Insurance Losses

One possible measure of the cost of the GSEs’ exposure to

credit risk is the present value of expected insurance losses

based on the distribution of possible outcomes in a given year,

which essentially weights those outcomes in proportion to their

likelihood of occurring. That measure is the insurance- loss

component of the GSEs’ budgetary cost as estimated in accor-

dance with the rules specified in the Federal Credit Reform Act

of 1990 (FCRA).

The present value of expected losses would rise if the GSEs’

policies changed in ways that widened the distribution of

credit losses, such as a shift to guaranteeing mortgages with

higher loan- to- value ratios. But the present value of expected

losses would remain the same if policies changed in ways that

increased the likelihood of losses in weak economic conditions

and produced an equally likely reduction in losses in stronger

economic conditions.

Insurance- Loss Component of a Fair- Value Estimate

An alternative measure of the GSEs’ exposure to credit risk—

which the Congressional Budget Oce uses in this analysis—is

the insurance- loss component of a fair- value estimate of the

GSEs’ cost. That measure is more comprehensive than the

FCRA measure described above because, by including an

adjustment for market risk, it implicitly puts more weight on

losses that occur in adverse economic conditions. As a result,

the fair- value measure of credit risk would rise (rather than

remain the same) if policies changed in ways that increased the

likelihood of losses in weak economic conditions and produced

an equally likely reduction in losses in stronger economic

conditions.

13deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

for inclusion in the reference pool for credit- risk notes,

CBO estimates—because, for example, they have a

loan- to- value ratio below 60percent, have adjustable

interest rates, or are guaranteed under certain renancing

programs. As an illustrative example, if the GSEs issued

credit- risk notes covering all of the loans they guaran-

teed in 2018, they would increase the amount of risk

exposure transferred to investors from $2.8billion to

$3.9billion.

25

Second, credit- risk notes have an average maturity of 10

to 12years, much shorter than the 30- year term of most

mortgages in their reference pool. As a result, any losses

that the GSEs experience on that pool after the notes

have matured are not shared with the notes’ investors. If

the GSEs issued credit- risk notes with the same maturity

25. In the illustrative examples in this section, estimates of the

amount of risk exposure transferred to investors are based on

the assumption that the spreads required by investors would not

change with the changes to credit- risk notes. CBO measures the

value of risk exposure transferred to investors as the present value

of the expected interest payments on the notes, so changes in

the spreads required by investors would alter the amount of risk

exposure transferred.

as the reference loans, the amount of risk exposure

transferred to investors on the 2018cohort of guarantees

would increase from $2.8billion to $3.3billion.

ird, borrowers’ scheduled and unscheduled repay-

ments of principal reduce the amount of credit- risk

notes outstanding and thus the capacity of those notes

to absorb losses. If the GSEs did not use principal

repayments on the reference loans to repay note holders,

the amount of risk exposure covered by the 2018notes

would rise from $2.8billion to $4.6billion.

If the GSEs made all three of those changes simultane-

ously, investors would be at risk for $11.7billion (or

46percent) of the $25.3billion in expected fair- value

losses on the 2018cohort of guarantees. As a result, the

GSEs would bear only 54percent of that risk exposure

rather than 89percent.

26

However, adding loans with

dierent credit- risk proles (such as adjustable- rate

26. e 54percent of risk exposure retained by the GSEs in

this example includes the expected fair- value losses below

3.75percent of the reference pool’s UPB that are not transferred

to investors through credit- risk notes and the expected fair- value

losses above 3.75percent of the UPB.

Figure 3 .

Risk Exposure on the GSEs’ 2018 Cohort of Guarantees Under Current Policy and Option 1

Billions of Dollars

25.3

22.5

21.9

21.1

2.8

3.4

4.1

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Without Credit-Risk

Transfers

Under GSEs' Current Policy

of Credit-Risk Transfer

Option 1A (GSEs Transfer a

Larger Share of the

Currently Covered Losses)

Option 1B (GSEs Transfer

Losses Up to a Higher

Percentage of UPB)

Risk Exposure Borne by CRT Investors

Risk Exposure Borne by the GSEs

Risk Exposure Borne by CRT Investors

Risk Exposure Borne by the GSEs

Option 1B

(GSEs Transfer

Losses Up To a

Higher Percentage

of the UPB)

Option 1A

(GSEs Transfer a

Larger Share of the

Currently Covered

Losses)

Under GSEs’

Current Policy

of Credit-Risk

Transfers

Without

Credit-Risk

Transfers

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

CRT = credit- risk transfer; GSEs = government- sponsored enterprises (in this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac); UPB = unpaid principal balance.

14 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

mortgages or loans with very low loan- to- value ratios)

or making structural changes to the notes (such as

extending the term or eliminating principal amortiza-

tion) would represent signicant changes to the CRT

program.

Amount of Risk Transferred Under the Options. As

opposed to such structural changes, the options that

CBO analyzed would allow the GSEs to increase the

amount of risk they share with private investors on a

more incremental basis. Option1A—transferring a

larger portion of the losses up to 3.75percent of the

UPB of the reference pool—would increase the risk

exposure borne by investors on the 2018cohort of

guarantees by $0.6billion (from $2.8billion to $3.4bil-

lion).

27

Option1B—selling notes that cover losses up to

6percent of the reference pool’s UPB—would boost the

risk exposure borne by investors by $1.3billion (from

$2.8billion to $4.1billion). Despite those expansions of

risk sharing, the GSEs would retain the majority of risk

exposure on the mortgages they are projected to guaran-

tee in 2018 (see Figure 3).

Option 2—selling credit- risk notes based on reference

pools of loans guaranteed between 2008 and 2012—

would increase the risk exposure borne by investors by a

total of $2.2billion (see Figure 4). at amount rep-

resents 9percent of the estimated $23.7billion in risk

exposure on those loans.

e amount of risk exposure on each annual cohort

of guaranteed loans, and how much of that risk expo-

sure would be transferred to investors under a standard

credit- risk note, would depend on the UPB remaining

and the composition of the loans in 2018. For example,

mortgages guaranteed by the GSEs in 2008that are

expected to still be outstanding in 2018have less total

UPB and risk exposure than mortgages guaranteed in

2012, because most of the loans in the 2008cohort

will have either been repaid in full or defaulted by

2018. Measured per dollar of outstanding UPB, how-

ever, those 2008loans have much more risk exposure

than the loans guaranteed in 2012. e main reason

is that, in CBO’s estimation, the 2008mortgages have

higher current loan- to- value ratios (which rose when

home prices declined during the housing crisis) and the

27. For more detail about CBO’s budget estimates of CRTs under the

baseline and the options, see Supplemental Table1, available at

www.cbo.gov/publication/53380.

Figure 4 .

Risk Exposure on the GSEs’ 2008–2012 Cohorts of

Guarantees Under Option 2

Billions of Dollars

23.7

21.5

2.2

0

5

10

15

20

25

Without Credit-Risk Transfers Option 2 (GSEs Share Risk on

Mortgages Guaranteed Between

2008 and 2012)

Risk Exposure on 2008–2012 Cohorts

1.9

1.6

0.3

0

4

8

12

Without Credit-Risk Transfers Option 2 (GSEs Share Risk on

Mortgages Guaranteed Between

2008 and 2012)

Risk Exposure on 2008 Cohort

10.6

9.8

0.8

0

4

8

12

Without Credit-Risk Transfers Option 2 (GSEs Share Risk on

Mortgages Guaranteed Between

2008 and 2012)

Risk Exposure on 2012 Cohort

Risk Exposure Borne

by CRT Investors

Risk Exposure

Borne by the GSEs

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

CRT = credit- risk transfer; GSEs = government- sponsored enterprises (in

this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

15deCeMber 2017 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC

borrowers have lower average credit scores, resulting in

higher estimated default losses per dollar of outstand-

ing UPB. Nevertheless, because fewer 2008loans than

2012loans remain outstanding, credit- risk notes based

on 2008loans would transfer less total risk exposure

than notes based on 2012loans ($0.3billion versus

$0.8billion).

Eects on the GSEs’ Annual Net Premiums

A measure of the nancial standing of Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac is the net income generated by their

operations. at net income is particularly relevant

for policymakers now, while the GSEs are in conserva-

torships. Under the terms of agreements signed when

the government took over the GSEs, in any quarter in

which Fannie Mae’s or Freddie Mac’s net worth becomes

negative, the Treasury is obligated to buy enough stock

(subject to limits) from the GSEs to restore them to posi-

tive net worth.

28

In return, the GSEs must pay dividends

to the Treasury on the government’s holdings of that

stock.

29

CBO estimates the budgetary impact of the GSEs on

a fair- value basis rather than on the basis of their cash

transactions with the Treasury, but CBO does estimate

some of the GSEs’ cash ows in order to calculate the

annual net premiums they collect as a part of their guar-

antee operations. Net premiums consist of the income

that the GSEs collect from guarantee premiums minus

the losses they bear on the loans they guarantee. For

loans that serve as part of a reference pool for a credit-

risk note, annual net premiums also reect the interest

paid to the note’s investors and the losses borne by those

investors under the terms of the CRT transaction.

30

Although annual net premiums dier from net income,

they provide guidance for estimating whether the

GSEs’ guarantee operations are likely to require further

28. For more details about the relationship between the GSEs’

earnings and payments by the Treasury, see Congressional Budget

Oce, e Eects of Increasing Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s

Capital (October2016), www.cbo.gov/publication/52089.

29. Under the current terms of the agreements, when Fannie Mae’s

or Freddie Mac’s net worth exceeds a specied threshold (set to

decline to zero in 2018), that GSE must pay dividends to the

Treasury equal to the amount above the threshold.

30. CBO’s interest calculation includes income that the GSEs earn by

investing the funds they receive from the sale of credit- risk notes.

Because the GSEs could use those funds instead of borrowing,

the rate of return that CBO uses to calculate interest is based on

the GSEs’ borrowing costs.

payments (in the form of stock purchases) from the

Treasury.

31

If economic conditions turn out to be consistent with

CBO’s macroeconomic forecast, the mortgages that the

GSEs are expected to guarantee in 2018will generate

positive net premiums each year through 2030, CBO

estimates (see Figure 5).

32

In 2018, those net premiums

are projected to equal about 0.2percent of the origi-

nal principal guaranteed, meaning that the guarantee

premiums collected by the GSEs on those loans exceed

the sum of interest paid to holders of credit- risk notes

and any losses that occur in that rst year. Net premiums

are projected to rise in 2019 to more than 0.3percent of

the original principal balance as some of the loans in the

2018cohort begin to be repaid early and as the GSEs are

allowed to recognize as income the full value of premi-

ums assessed on the borrower when a guarantee is made.

Annual net premiums then begin to decline, eventually

falling below 0.1percent of the original principal guar-

anteed, as the outstanding principal of the 2018cohort

decreases (because of repayments and defaults) and guar-

antee premiums are collected on that smaller amount of

principal.

Eects of Current CRT Policy. Under the economic

conditions in CBO’s macroeconomic forecast, the GSEs’

current credit- risk- transfer policy reduces annual net

premiums slightly, CBO estimates, because the cost of

interest paid to investors exceeds the value of the losses

borne by those investors. at estimate is consistent with

the expectation that investors will require compensation

that will cover liquidity risk and some level of losses

greater than those expected under normal economic

circumstances.

Credit- risk transfers are nancially benecial to the

GSEs under more adverse economic conditions. For

example, in a scenario consistent with the “severely

adverse” stress scenario that the Federal Reserve uses in

its Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review exercise

31. In addition to annual premiums from guaranteeing single- family

mortgages, the GSEs’ net income is aected by their guarantees

of multifamily mortgages and their investments in mortgage-

related securities to hold in their portfolios of assets. Other

factors that inuence net income include the results of hedging

operations and changes to the GSEs’ loss reserves (an estimate of

future guarantee claims).

32. For the dollar amounts of those estimates, see Supplemental

Table2, available at www.cbo.gov/publication/53380.

16 Transferring CrediT risk on MorTgages guaranTeedby fannie Mae or freddie MaC deCeMber 2017

for banks, the GSEs’ annual net premiums are projected

to be higher from 2020 to 2025under the GSEs’ current

CRT policy than they would be without credit- risk

transfers (see Figure 5).

33

(By the end of 2025, credit- risk

33. e severely adverse stress scenario features a decline of more

than 20percent in house prices and an unemployment rate rising

to 10percent. For more details, see Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System, 2017Supervisory Scenarios for Annual

Stress Tests Required Under the Dodd- Frank Act Stress Testing Rules

and the Capital Plan Rule (February2017), pp.5–6, http://

tinyurl.com/yclyaxfk (PDF, 331KB).

notes based on the 2018cohort are estimated to be fully

extinguished under the stress scenario as a result of both

principal repayments and losses borne by the investors.

After 2025, the notes have no eect on the GSEs’ net

premiums for the 2018cohort of guarantees under that

scenario.)

Translating annual net premiums into projected net

income is dicult, requiring many assumptions about

such things as accounting policy. Nevertheless, the results

under both CBO’s macroeconomic forecast and the stress

Figure 5 .