UMass Global UMass Global

UMass Global ScholarWorks UMass Global ScholarWorks

Dissertations

Spring 5-22-2022

Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education

Classroom: A Phenomenological Study Classroom: A Phenomenological Study

Roger Hattaway

University of Massachusetts Global

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.umassglobal.edu/edd_dissertations

Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons,

Disability Studies Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons,

Educational Technology Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hattaway, Roger, "Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education Classroom: A

Phenomenological Study" (2022).

Dissertations

. 447.

https://digitalcommons.umassglobal.edu/edd_dissertations/447

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UMass Global ScholarWorks. It has been accepted

for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UMass Global ScholarWorks. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education Classroom: A

Phenomenological Study

A Dissertation by

Roger B. Hattaway

University of Massachusetts Global

Irvine, California

School of Education

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership

April 2022

Committee in charge:

Philip O. Pendley, Ed.D., Committee Chair

Shani Cigarroa, Ed.D.

Carlos V. Guzman, Ph.D.

iii

Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education Classroom: A

Phenomenological Study

Copyright © 2022

by Roger B. Hattaway

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This doctoral journey has been an eye opening experience. It has taught me that

time stops for no man and that every second should be cherished. I have taken so much

time away from family and friends to pursue this degree and I want to thank everyone for

their patience during this time.

The conclusion of this journey could not have been made possible without the

support of my dissertation chair and committee. Dr. Pendley has been a great support

element and has given of his time freely to ensure that the journey was fruitful. His

knowledge and dedication have been second to none. Dr. Guzman, I can’t decide if his

teachings or his music has been the greater inspiration, but both are well worth my time.

Just close your eyes and open your mind, the fruits of his labors are ripe for the taking.

Dr. Cigarroa was an inspiration before we even met. I learned so much from her work

and it has helped make this process easier than I had expected it to be. She has been a

true inspiration and a true ambassador of the Brandman program. Thank you all for your

dedication to future doctors.

To my wife, I thank you for not letting me give up when I was tired. The past 25

years have been the most joyous of my life, and it is because of you. You were there

during my 20 years of service in the United States Marine Corps, waiting for me to return

from wherever the Corps took me. You moved with me countless times, never

complaining about having to pick up all that you have and leaving your friends and

family. You have put up with my complaining and grumblings about work, and about

life in general, without making me feel as though I am burdening you. I truly do not

know what I would do without you in my life.

v

To my children, thank you all for accepting the multiple moves from one side of

the country to the next, and back again, leaving your friends so that I could chase the

dream of retiring from the military. You have sacrificed so much, and I want you to

know that I understand and respect the sacrifices that you have made. I also want to

thank you for understanding when I had to miss weekend events due to schoolwork. I

hope that I have been as inspiring to you as you have been to me. I love you all so much

and hope to be able to help you reach your goals in life, whatever they may be.

My Brandman family, we have put the function in dysfunction. I have grown

from the ups and downs of this Motley Crew and believe that I have a better

understanding of the word empathy. We have shared so much more than just book

knowledge; we have shared life stories that have touched each other’s lives in a way that

will live forever. There were times when I did not believe that we would make it on

some of the team projects, but just when it had to happen, we made it come together, and

it was a work of art. I truly hope that we all get to work together in some capacity and

continue this growing process.

Dr. Hadden, thank you for your mentorship and for putting up with this rowdy

bunch. We made it difficult on you at times, but your tenacity and calm demeanor

brought us through the roughest of times. I hope and pray that your mansion has a deck

for you to sit and watch the ships go by.

Sitting on my deck

The big ships go slowly by

Destination known

vi

ABSTRACT

Music as a Form of Therapy in the K-4 Special Education Classroom: A

Phenomenological Study

by Roger B. Hattaway

Purpose: The purpose of this phenomenological study was to identify and describe the

perceptions of elementary K-4th grade teachers on the effects of music therapy as it

pertains to academics and behavioral incidents in the special education classroom

(Gooding, 2010).

Methodology: This qualitative study used a phenomenological design to ascertain the

perception of the teachers on the impact of music therapy regarding academics of

students in the K-4 grade special education classroom. The data were collected using the

descriptive narrative to ascertain the perception of the changes in academics and behavior

gathered from the interview questions.

Findings: Analysis of the phenomenological qualitative data showed that music has a

positive effect on both academics and behavior in the K-4th grade special needs

classroom. Data shows that music played as background noise allows the students to stay

focused and add a calming effect to the classroom. The study found that music relieves

anxiety and increases peer and staff relationships.

Conclusion: Resulting themes deduced from the qualitative interviews support the

efficacy of music as a form of therapy in relation to academics and behavior in the K-4th

grade classroom as it pertains to students with special needs. These findings prove the

institutional need to support music as a form of therapy in the classroom.

Recommendations: It is recommended that the following six areas be pursued: (a) A

mixed methods study be conducted to include the academic scores from California and

vii

Washington state tests, (b) a study that includes schools from a more diverse region, (c)

include the paraprofessionals to ascertain their perspective, (d) including the perspective

of parents of the special needs students, (e) replicate the study in the general education

classroom to see what effects music as a form of therapy could have, and (f) conduct a

study in later grade levels utilizing music selected by the teacher and music selected by

the students to understand if the choice of music influences the outcome of the study.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1

Background ......................................................................................................................... 2

Historical Perspective of Music Therapy ...................................................................... 2

Contemporary Perspective of Music Therapy ............................................................... 5

Special Education .......................................................................................................... 7

Applying Music Therapy on the Perceptions of Special Education Students ............... 9

Gap in Literature ......................................................................................................... 11

Statement of the Research Problem .................................................................................. 11

Purpose Statement ............................................................................................................. 12

Research Questions ........................................................................................................... 12

Significance of the Study .................................................................................................. 12

Definitions......................................................................................................................... 14

Delimitations ..................................................................................................................... 16

Organization of the Study ................................................................................................. 16

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW ......................................................................... 17

Historical Perspective of Music Therapy .......................................................................... 17

World War II ............................................................................................................... 17

Social Aspect ............................................................................................................... 19

Physical Rehabilitation ................................................................................................ 20

Treatment of Depression ............................................................................................. 22

Treatment of Anxiety .................................................................................................. 23

Treatment of Stress ...................................................................................................... 25

Contemporary Perspective of Music Therapy .................................................................. 27

Cognitive Development ............................................................................................... 28

Emotional Development .............................................................................................. 30

Physical Development ................................................................................................. 33

Social Development .................................................................................................... 35

Special Education.............................................................................................................. 38

No Child Left Behind Act / Individuals with Disabilities Education Act ................... 38

Intervention Strategies ................................................................................................. 41

Applying Music Therapy .................................................................................................. 43

Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................... 44

Research Gap .................................................................................................................... 45

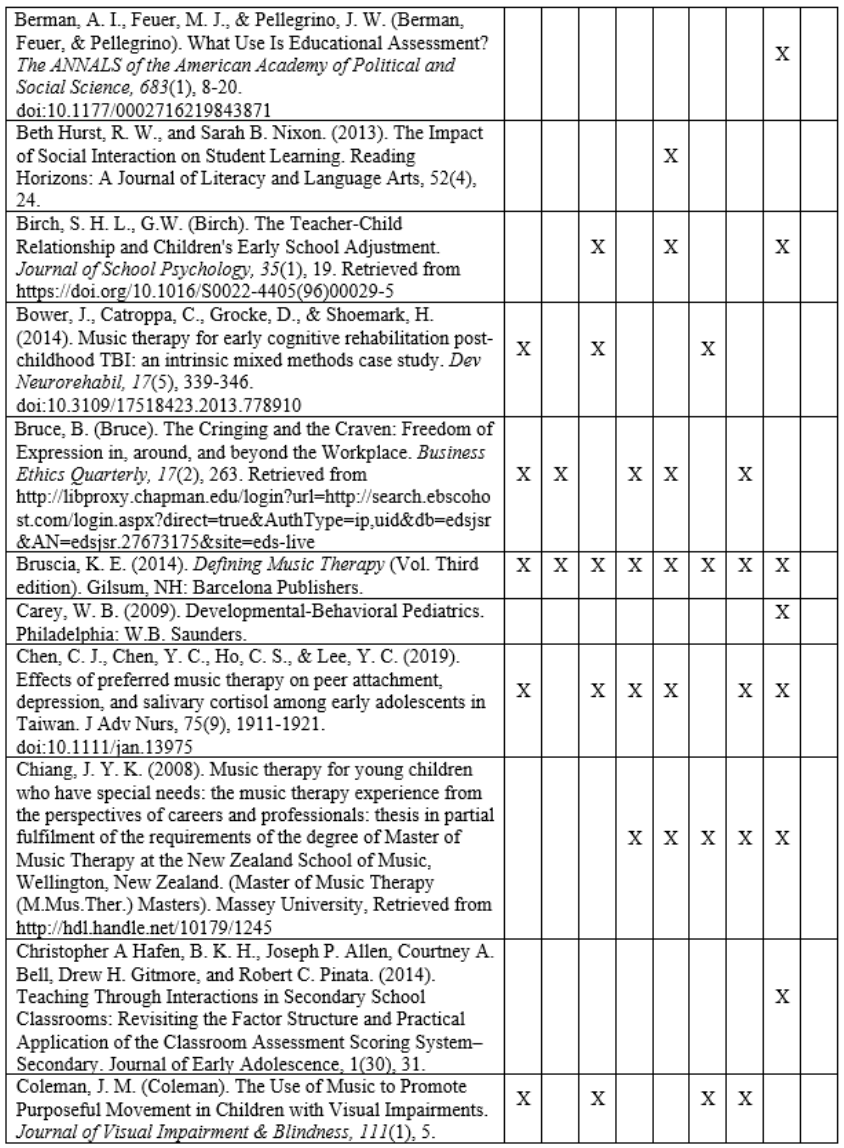

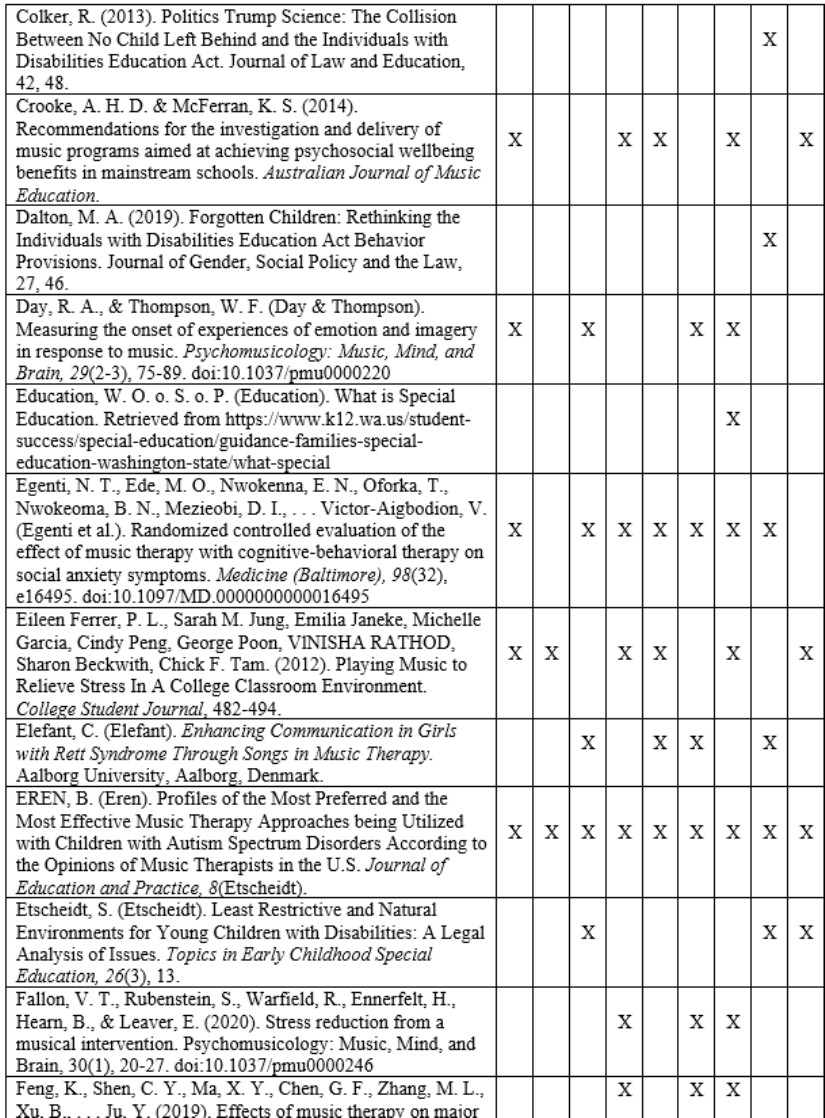

Synthesis Matrix ............................................................................................................... 47

Summary ........................................................................................................................... 47

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY .................................................................................. 49

Purpose Statement ............................................................................................................. 49

Research Questions ........................................................................................................... 49

Research Design................................................................................................................ 50

Qualitative Research Design ....................................................................................... 50

Population ......................................................................................................................... 51

Sampling Frame .......................................................................................................... 52

Sample ......................................................................................................................... 53

ix

Sampling Process ........................................................................................................ 53

Instrumentation ................................................................................................................. 54

Qualitative Instrumentation ......................................................................................... 55

Qualitative validity .................................................................................................. 55

Qualitative reliability ............................................................................................... 56

Qualitative field test ................................................................................................. 56

Data Collection ................................................................................................................. 56

Qualitative Data Collection ......................................................................................... 57

Ethical Considerations ...................................................................................................... 57

Data Analysis .................................................................................................................... 57

Qualitative Data Analysis ............................................................................................ 58

Limitations ........................................................................................................................ 58

Summary ........................................................................................................................... 59

CHAPTER IV: RESEARCH, DATA COLLECTION, AND FINDINGS....................... 60

Overview ........................................................................................................................... 60

Purpose Statement ............................................................................................................. 60

Research Questions ........................................................................................................... 60

Research Methods and Data Collection Procedures ......................................................... 61

Population ......................................................................................................................... 62

Sample ......................................................................................................................... 63

Sampling Process ........................................................................................................ 63

Presentation and Analysis of Data .................................................................................... 65

Interview Question Results ............................................................................................... 66

Academic Performance ............................................................................................... 66

Interview question 1................................................................................................. 66

Interview question 2................................................................................................. 67

Interview question 3................................................................................................. 68

Interview question 4................................................................................................. 69

Interview question 5................................................................................................. 70

Behavioral ................................................................................................................... 71

Interview question 1................................................................................................. 71

Interview question 2................................................................................................. 73

Interview question 3................................................................................................. 74

Interview question 4................................................................................................. 75

Interview question 5................................................................................................. 76

Interview Conclusion Questions ....................................................................................... 77

Overall Frequency of Themes for all Research Questions ............................................... 81

CHAPTER V: FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............. 83

Overview ........................................................................................................................... 83

Purpose Statement ............................................................................................................. 83

Research Questions ........................................................................................................... 83

Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 84

Population and Sample ..................................................................................................... 84

Major Findings .................................................................................................................. 86

Research Question 1 .................................................................................................... 87

x

Major finding 1 ........................................................................................................ 87

Research Question 2 .................................................................................................... 87

Major finding 2 ........................................................................................................ 88

Major finding 3 ........................................................................................................ 88

Unexpected Findings ........................................................................................................ 89

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 90

Conclusion 1 ................................................................................................................ 90

Conclusion 2 ................................................................................................................ 91

Implications for Action ..................................................................................................... 91

Implication 1 ................................................................................................................ 91

Implication 2 ................................................................................................................ 92

Implication 3 ................................................................................................................ 92

Recommendations for Further Research ........................................................................... 93

Recommendation 1 ...................................................................................................... 93

Recommendation 2 ...................................................................................................... 93

Recommendation 3 ...................................................................................................... 93

Recommendation 4 ...................................................................................................... 94

Recommendation 5 ...................................................................................................... 94

Recommendation 6 ...................................................................................................... 94

Recommendation 7 ...................................................................................................... 94

Concluding Remarks and Reflections ............................................................................... 95

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 96

APPENDICES ................................................................................................................ 112

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Teachers Per Grade Level, California ............................................................. 51

Table 2. Teachers Per Grade Level, Washington State ................................................ 52

Table 3. Participants by District and Grade Levels ...................................................... 54

Table 4. Participants by District and Grade Levels ...................................................... 65

Table 5. Characteristics of Participants ........................................................................ 65

Table 6. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Attention Span .................................................... 67

Table 7. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Time on Task ...................................................... 68

Table 8. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Completion of Task............................................. 69

Table 9. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Accuracy of Completed Work ............................ 70

Table 10. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Performance on Assessments .............................. 71

Table 11. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Behavioral Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Interaction with Classmates ................................ 72

Table 12. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Behavioral Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Interaction with Staff .......................................... 74

Table 13. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Behavioral Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Self-Control......................................................... 75

xii

Table 14. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Behavioral Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Following Class Rules ....................................... 76

Table 15. Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Behavioral Performance in the

Classroom with Respect to Number of Referrals .......................................... 77

Table 16. Closing Thoughts on the Impact of Music Therapy on Students’ Academic

and Behavioral Performance in the Classroom ............................................. 81

Table 17. Overall Combined Frequencies of Themes from all Research Questions ..... 82

1

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization in 2001, up to 20% of children and

adolescents are affected by mental illness worldwide (Porter et al., 2017).

Internationally, mental health disorders account for the most considerable burden of

youth issues. (Gold, Saarikallio, Crooke, & McFerran, 2017). Some of the more common

mental health disorders among youth are attention-deficit/hyperactivity, anxiety,

depression, conduct disorders, bipolar disorder, autism, and psychosis. Attention-

deficit/hyperactivity is a disorder that causes the student to feel tired, depressed, anxious,

or become easily distracted. Depression causes children to feel irritated or sad for long

periods of time. It is estimated by the Center for Disease Control that there are nearly

45,000 American deaths each year from depression-related issues. Anxiety, the most

common illness affecting children, can cause children to become so afraid of situations

that it interferes with their daily activities. “Anxiety disorder and anxiety symptoms

could have a long-term negative impact on adolescents' academic performance,

interpersonal relationships, and psychological well-being” (Kwok, 2018, p. 663).

Music can be used as a mood enhancer. Music, when used as mood enhancers,

changes the way people work within a particular setting (Fletcher, 2004). Playing music

can allow the listener to remove themselves from the monotony of the daily tasks and

provides freedom of expression. Freedom of expression allows the listener to feel more

involved in the process and allows the individual the freedom to be creative and complete

the tasks at hand (Bruce, 2007).

“Emotional states, familiarity, and properties of musical structure combine to

create a psychological environment that is conducive to the generation of visual imagery.

2

That imagery, in turn, may amplify or modify a necessary emotional experience” (Day &

Thompson, 2019, p. 75).

Background

Historical Perspective of Music Therapy

According to the 1998 working definition, as given by Bruscia, (2014), music

therapy is a structured process of intercession wherein the therapist helps the client to

increase health, using music experiences and the interrelations that develop through them

as energetic forces of change. The World Federation of Music Therapy (WFMT) defines

music therapy as follows:

It is the use of music and musical elements professionally to optimize the quality

of life of individuals, groups, families, or communities and to improve their

physical, social, communicative, spiritual, intellectual, emotional health and well-

being as a means of intervention in educational and medical fields or in daily life.

(as cited in OsmanoĞLu & Yilmaz, 2019, p. 19)

Music has been used as a form of therapy since World War II (Foran, 2009). It

was first used to help those coming back from the war rehabilitate from traumatic brain

injuries (TBI). TBI account for the most significant number of disabilities and death

among children worldwide (Bower, Catroppa, Grocke, & Shoemark, 2014). It has since

been used in many other settings to include helping to relieve the stress of college

students, and students of all grade levels (Ferrer et al., 2012).

The diagnoses covered by music therapy ranges from physical impairments

caused by (a) physical and neurological trauma (amputations, brain injury, burns, spinal

cord injury, coma, fractures, orthopedic impairments, hip dislocation); (b) specific

3

illnesses and conditions (asthma, arthritis, poliomyelitis, epilepsy, hemophilia, tension

headache); (c) congenital developmental diagnoses (autism, cerebral palsy, learning

disorders, scoliosis, spina bifida, visual impairments); and (d) degenerative diseases (e.g.

dementia, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis) (Weller & Baker,

2011). TBI account for the most significant number of disabilities and death among

children worldwide (Bower et al., 2014).

In an advanced American evaluation of 148 studies with children having

intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) it was established that music therapists

earmarked a range of clinical conclusions including learning, behavioral, social, physical,

and communication skills (Thompson & McFerran, 2014). Sensory processing disorder

(SPD) is a disturbance in the organization of sensory input that affects relevant responses

to the insistence of the surroundings. The results of SPD in children may include a

developmental delay as well as behavioral and emotional issues. Music therapy should

be peculiarly suitable for children with an SPD because music and the sensory system are

both connected to the nervous system. This advocates there is a need to greater

understand the correlation between the sensory system and the aspects of music (Simhon,

Elefant, & Orkibi, 2019).

Studies have shown that the use of music in counseling sessions can escalate the

production of all four beneficial hormones present in the human body, namely dopamine,

endorphins, oxytocin, and serotonin (Situmorang, Mulawarman, & Wibowo, 2018). The

release of these positive hormones contributes to the belief that the use of music therapy

with cognitive-behavioral therapy is noteworthy in lessening social anxiety among

schooling adolescents (Egenti et al., 2019). Results in a study suggested a sizeable

4

reduction in preoperative anxiety for both pediatric patients and their custodians

regardless of active or passive music therapy intercessions (Millett & Gooding, 2018). A

video examination of deliberate communication in music therapy with females who have

Stage III and IV Rett syndrome exhibited an increase in the sound selection of favored

songs, despite the negative learning trajectory expected for people with this

neurodegenerative disorder (Elefant, 2002).

Music can be used socially to allow people to express themselves in a manner that

does not require them to come up with dialog to fit the social setting. To relax, celebrate,

help us think, and to morn, we tend to listen to the different genres of music (Foran,

2009). Music therapy scholars suggest specific characteristics are necessary for the

possession of psychosocial wellbeing profits, such as tailored and client-centered

delivery, that are not easily obliged by music education programs (Crooke & McFerran,

2014). Students with higher social skills tend to have less daily stress, and stress is

known to not only reduce the level of work but is linked to many health problems (Ferrer

et al., 2012). Previous research has proposed that a lack of social competence makes it

difficult to grow constructive relationships with peers and teachers in elementary school

(Birch & Ladd, 1997). Results of a qualitative systematic review conducted by Palazzi,

Wagner Fritzen, and Gauer (2018), showed that music is a dynamic and engaging

stimulus that governs decision-making processes and risk-taking, increases pro-sociality,

and affects behavioral decisions.

As of 2017 figures propose that 2.6% of young people worldwide suffer from

depression; often connected with diminished social functioning and education fulfilment

(Porter et al., 2017). U.S. numbers estimate that 20% of adolescents will encounter a

5

depressive episode by the age of 18 (Porter et al., 2017). A review of studies using

randomized‐controlled trials (RCTs) and clinical controlled trials (CCTs) of individuals

recognized as having clinical depression and going through either treatment as usual,

psychological therapies, pharmacological therapies or a form of music therapy, showed

that a significant, short‐term improvement in depressive symptoms, level of functioning,

and anxiety can be seen in individuals going through music therapy together with usual

treatment when compared with a group experiencing treatment as usual (Roddis &

Tanner, 2020).

Anxiety disorder and anxiety symptoms may have a long-term negative influence

on adolescents’ interpersonal relationship, academic performance, and psychological

well-being. Past studies also revealed that excessive anxiety impedes children’s coping

ability, causes negative emotional behavior, and leads to disruptive behavior, low self-

concept, attention and learning disorders, and depression in the long-term (Kwok, 2018).

According to OsmanoĞLu and Yilmaz (2019) music can lead us to feel happy, creative,

and enthusiastic and to think positively and can treat mental illnesses caused by anxiety

and stress. “As a result of a review of related literature, it was found that there is a

general agreement on the positive effects of classical music on human psychology in

terms of reducing anxiety and stress and promoting well-being” (OsmanoĞLu & Yilmaz,

2019, p. 20).

Contemporary Perspective of Music Therapy

Cognitive development is believed to begin while we are still in the womb.

Mothers sing to their unborn children in hopes that it will somehow increase the

connection between mother and child. According to Wallace (2000), a fetus will jump to

6

the beat of a drum. The pregnant mother must pay attention to what she is taking into her

body due to the fetus taking in portions of that same material. It may also be just as vital

for the mother to be cognizant of the sounds around her. Loud noises have shown to

cause the heart rate to increase in the mother and have the same effect on the unborn

fetus. These symptoms can extend beyond the womb and stay with the child throughout

adolescence. Research conducted by Nussberger and Teckenberg (2016) shows that

music therapy used to relax the mother while she is carrying the child reduces the stress

that is felt by the unborn child and reduces the risk of “preterm delivery and perinatal

complications, ante- and postnatal depression, early interaction disturbances”

(Nussberger & Teckenberg, 2016, p. 105).

The reason that people listen to music, and the type of music chosen has been a

topic of research for many years. Many factors can play a significant role in why people

listen to music and determine their musical preference. Many studies have shown all

around that music has been used to bring about emotional states, activate, express, relax,

control emotions, and communicate (Tekin Gurgen, 2016).

Physical therapy may use music in many different forms and for many different

reasons. Vibroacoustic, for example, is the non-invasive technique of using different

frequencies of music to target the different parts of the body providing pain relief from

different ailments. There is evidence that vibroacoustic therapy and its use of low

frequencies can be relaxing and has a physical effect on lower back pain in adolescents

(Dudoniene et al., 2016). Pain is alleviated without the use of medicine using different

frequencies, targeting the different areas of the body.

7

In physical therapy, music has also been used in the management of pain. Music

administered during physical therapy may provide a form of distraction to the patient

allowing the patient to be more at ease during what some feel to be physically agonizing.

A study approved by the Siena University Hospital ethical committee showed that adult

patients had a significant reduction in the perception of pain during physical therapy

when given music to listen to during the process (Bellieni et al., 2013).

Visually impaired individuals are using therapeutic music devices to help with

movement from one area to another. The Soundbeam device produces sound through

sensor technology that allows students to create music through movement vice the use of

instruments (Coleman, 2017). Using the Soundbeam technology should allow students

who would typically be reluctant to move around a room, due to their inability to see

well, walk around to make music. Moving around in this manner can give visually

impaired students a reason to get up and can add a physical element to their day.

Social skills grow through the interaction of individuals within different settings

and from different backgrounds. Powerful social skills are an important part of

functioning successfully (Gooding, 2010). Studies have shown that adding music

activities in the curriculum promotes social learning by providing a social context for the

acquisition of new skills (Walworth, 2009)

Special Education

According to the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Education

(2020), “special education is specially designed instruction that addresses the unique

needs of a student eligible to receive special education services” (What is Special

Education section, para. 1). Although a goal of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of

8

2001 was to improve academic results for all students, the Individuals with Disabilities

Education Improvement Act (IDEA) focused on this goal by improving access to the

general education curriculum for students with disabilities. Both acts put forward the

belief that students’ outputs and levels of achievement are connected to expectations set

forth by the teachers (Parrish & Stodden, 2009). “The IDEA mandates that each state

must establish, to the maximum extent appropriate, that early intervention services are

provided in natural environments, including the home and community settings in which

children without disabilities live” (Etscheidt, 2006, p. 167).

In 2019 it was estimated that approximately 13% of public school children obtain

special education and related services; and psychological and educational evaluations are

used to identify children who may need services, establish eligibility and classification of

students who need supplemental educational services, monitor progress, plan for

interventions, refine educational approaches, and provide accountability (Berman, Feuer,

& Pellegrino, 2019). Although there are federal and state guidelines on what defines a

disability, there are no specified guidelines or assessments on how to determine if a child

has special needs. The students are characterized using subjectivity by the school system

and administration.

In a study conducted by Batchelor and Taylor (2005) there were six identifiable

interventions commonly used within the early childhood setting:

• Child-specific social interventions which are strategies aimed at each

individual child based on their needs.

• Affective interventions which are group focused based on changing the

attitudes of peers towards children with disabilities.

9

• Friendship activity interventions, which redesign children songs, group

games, and social activities that promote social interactions.

• Incidental teaching of social skills which occurs when the teacher uses

incidents that happen during social interaction.

• Social integration activity interventions, which is pairing children with

disabilities with those who are highly socially competent.

• Peer-mediated intersessions which are programs designed to train typically-

developing peers with the social skills needed to coerce children with

disabilities into the play.

Applying Music Therapy on the Perceptions of Special Education Students

Listening to music in the classroom has shown to have positive effects on

students' relationships, memory, math ability, productivity, emotions, and overall health

(Fletcher, 2004). Music is used in early education to increase the likelihood of learning a

language as well as memory building (Foran, 2009). According to Day and Thompson

(2019), “emotional states, familiarity, and properties of musical structure combine to

create a psychological environment that is conducive to the generation of visual imagery.

That imagery, in turn, may amplify or modify a necessary emotional experience” (Day &

Thompson, 2019, p. 75). Being able to perceive yourself in a comforting place could add

a calming effect to one's outlook. Calming music therapy is effective at helping with

psychological situations, so using music in the classroom to help relieve stress is essential

(Fernandes & D'silva, 2019). It has since been used in many other settings to include

helping to relieve the stress of college students, and students of all grade levels (Ferrer et

al., 2012).

10

Music therapy approaches have been studied for possible connections between

music therapists' preferences, and opinions concerning the effectiveness of music therapy

methods for the use with adolescence with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Eren, 2017).

Results showed that behavioral approach, sensory integration approach to music therapy,

and creative music therapy were found as most preferred and most effective music

therapy approaches (Eren, 2017). Although behavioral approach was the primary

preference of music therapists, sensory integration approach was reported as the most

effective approach for the use with children with ASD (Eren, 2017).

The behavioral approach to music therapy rests on the defining characteristic of

music therapy as the scientific application of music to accomplish therapeutic

aims whether they are behavioral, developmental and/or medical. It is the use of

music and the therapist’s self to influence changes in behavior. (Madsen, Cotter,

& Madsen, 1968, pp. 15-16)

Patterned sensory enhancement involves the translation of musical elements to match the

spatial, temporal, and force components of complex functional movements (Imogen,

Clark, & Taylor, 2012). Using the creative music therapy approach, the music therapist

uses multiple techniques to find what best works for the patient. It could include

humming at a specific rate to allow the patients heartbeat to slow down or speed up

depending on the desired outcome, or it could be the rhythmic beating of a drum to

increase or decrease a patient’s heartbeat, depending on the needs of the patient

(Haslbeck, 2013).

11

Gap in Literature

The prospects for music programs to encourage psychosocial wellbeing in

mainstream schools is accepted in both policy and research literature. Notwithstanding

this perception, there is a deficiency of consistent research evidence supporting this link

(Crooke & McFerran, 2014). Despite what is known about the generality and effects of

mental health issues in adolescence and the far reaching entanglement for adulthood, the

evidence base for effective intersessions is relatively weak. Currently, the most common

perspectives to treatment are medication and psychotherapy, both of which have an

inadequate evidence support for use with children and adolescents (Porter et al., 2017).

Statement of the Research Problem

“Music therapy in special education differs from music teaching in its emphasis

on the acquisition of non-musical skills, using music as a symbol of emotional and

personal growth rather than as a cognitive skill-set to be learned and practiced” (Rickson

& McFerran, 2007, p. 40). Early education teachers are intimate with using music and

rhythm as tools for teaching language and building memory. However, the prospect of

using music to help across all special education settings is largely unexplored (Foran,

2009).

A child is considered to have special needs if he or she shows deficits in any of

the following areas: (a) cognitive, (b) physical, (c) communicative, (d) social, or (e)

emotional (Rosen, 2011).

Research indicates that deficits in social functioning during childhood are linked

to a variety of negative outcomes including: (a) substandard academic

performance, (b) high incidences of school maladjustment, (c) expulsions and/or

12

suspensions from school, (d) high dropout rates, (e) high delinquency rates, (f)

impaired social relationships, (g) high incidences of childhood psychopathology

and (h) substance abuse. (Gooding, 2010, p. ix)

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this phenomenological study was to identify and describe the

perceptions of elementary K-4th grade teachers on the effects of music therapy as it

pertains to academics and behavioral incidents in the special education classroom

(Gooding, 2010).

Research Questions

The following research questions were developed to help guide the study:

1. How do K-4 special education teachers describe the impact of music therapy

on academic performance in the classroom with respect to attention span, time

on task, completion of tasks, completed work, and performance on

assessments?

2. How do K-4 special education teachers describe the impact of music therapy

on behavioral performance in the classroom with respect to interaction with

classmates, interaction with staff, self-control, following class rules, and

number of discipline referrals?

Significance of the Study

This study is significant given that it may help determine the effects of music

therapy on special education students as perceived by teachers who work directly with K-

4th grade students. The lack of research in this area allows for limited findings in

13

addressing the effects of music as a form of therapy in the special education K-4th grade

classroom.

Music may have the ability to influence the social and emotional state of being.

Music helps individuals access the depth of their being, renews memories, fulfills

emotional needs, hints at forgiveness, and ultimately sets the stage for renewal and

growth (Weiler & Gall, 2016). Finding ways to implement music as a form of therapy

for children with special needs might help them grow socially, emotionally, and

academically.

Music therapy aims to create potentials and/or restore functionality of the

individual so that he or she can attain better intra and interpersonal integration and

accordingly a better quality of life through prevention, rehabilitation, or treatment

(Rickson & McFerran, 2007). Music therapy has been used to address a broad spectrum

of diagnoses such as autistic spectrum disorder, Down Syndrome, hearing impairment,

visual impairment, cerebral palsy, global developmental delay, and learning difficulties

(Chiang, 2008). Studies have suggested that developmental changes have a higher

probability to occur for children who receive music therapy than those who do not

(Aldridge, Gustroff, & Neugebauer, 1995).

“Mental health difficulties relate to major interpersonal and social challenges.

Recent qualitative research indicates that music therapy can facilitate many of the core

elements found to promote social recovery and social inclusion” (Solli, 2015, p. 204).

The prospective for music programs to encourage psychosocial wellbeing in mainstream

schools is accepted in both policy and research literature (Crook & McFerran, 2014).

14

Despite this acknowledgement, there is a lack of research in using music as a

form of therapy to promote this well-being. Recent research into the physiology of music

has shown music to necessitate activation of cooperating hierarchical neural networks

including cognitive, motor, speech, and language neural pathways (Slavin & Fabus,

2018). With the acknowledgement by policy and research as to the effectiveness of

music on the psychosocial wellbeing, as well as the positive outcome of the use of music

for the activation of the neural networks, additional research can help reveal the effects of

music as a form of therapy in the special education K-4th grade classroom. These links

can be important in understanding the potential effects of music as a form of therapy to

ensure the highest quality of life for students with special needs.

Definitions

Terms relevant to the study are defined below to provide ease of understanding

for the reader.

Academic performance. According to Abdullah (2016), academic performance is

the knowledge learned which is evaluated by marks by a teacher and/or educational goals

set by students and teachers to be achieved over a specific time period.

Accuracy of completed work. Accuracy of work, as defined by the Personnel

Department of Santa Cruz County, California, is the extent to which work is free from

errors or omissions.

Attention span. Attention span refers to the length of time during which can

concentrate or remain interested (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

Behavioral incident. A behavioral incident is a single behavioral event which

happens separately or in a series with other events to create a behavioral sequence. Each

15

individual event has a well-defined beginning and end. “Although there's

a negative connotation to a behavioral incident, but some of these incidents are just

routine, everyday activities which follow a normal sequence” (Psychology Dictionary,

2013, Behavioral Incident section, para. 2).

Behavioral performance. Behavioral performance results from a balance between

adaptive flexible behavioral choices and more rigid, repetitive choices, which are

supported respectively by brain networks known as goal-directed and habitual brain

systems (Carey, 2009).

Completion of task. Completion of task represented the number of items

(elements) completed per assignment; if a response was provided, whether right or wrong

(Gickling & Armstrong, 1978).

Interaction with classmates. Interaction with classmates refers to the social

interaction between students in the classroom (Hurst, Wallace, & Nixon, 2013).

Interaction with staff. Interaction with staff denotes the emotional, organizational,

and instructional interactions in the classroom (Hafen et al., 2014).

Music therapy. “Music therapy is a systematic process of intervention wherein

the therapist helps the client to promote health, using music experiences and the

relationships that develop through them as dynamic forces of change” (Bruscia, 2014, p.

36).

Special education. According to the Washington Office of Superintendent of

Public Instruction (2020), special education refers to the extra services provided to

students who are deemed to have a disability hindering the learning process. A disability

is a handicap that interferes with a child's ability to learn. In general, the term “child or

16

student with a disability” is used to describe a child or student who has emotional,

mental, or physical impairments that affect one’s ability to learn.

Time on task. Time on task signifies the amount of time a student is interacting

with instructional content or activity via choral response, raising hand, listening, writing,

reading, responding to teacher instruction, or otherwise completing assigned task (K. C.

Herman, Reinke, Nianbo, & Bradshaw, 2020).

Delimitations

This study was delimited to K-4th grade special education teachers in schools that

provide music therapy in the states of California and Washington, United States.

Organization of the Study

This study is arranged in five chapters. Chapter I included an introduction,

background, problem, and purpose statements, along with research questions and

definitions. Chapter II contains an in-depth look into the literature dealing with music

therapy, physical ailments, mental disorders, treatments, strategies and expected

behaviors. Chapter III details the methodology of the study including the population,

sample, data collection method, analysis, and limitations of this study. Chapter IV

presents the detailed analysis of the study conducted, and Chapter V provides an

executive summary of the research and offers conclusions and recommendations for

future research.

17

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW

The priority for Chapter II was to compile research literature as it pertains to the

use of music as a form of therapy in the K-4th grade special education classrooms, on

academic and behavioral success. The literature review was arranged in four sections

including 15 subsections using a funneling process. The first section offers a look at the

historical perspective of music therapy starting with World War II. Section two describes

contemporary perspective of music therapy in relation to cognitive, emotional, physical,

and social development. Section three was centered on special education to include the

NCLB, the IDEA, diagnosis, treatment options, and intervention strategies. Section four

details the application of music therapy, goals and objectives of music therapy

intervention, and approaches to music therapy. These four sections are followed with a

review of the gap in literature and a summary of literature pertaining to music as a form

of therapy in the K-4th grade classroom with students identified as special needs.

Historical Perspective of Music Therapy

World War II

According to Foran (2009), music as therapy came to light in rehabilitation

settings in the United States for returning World War II veterans. “During this time,

interest in the rehabilitative potential of music exploded, and organizations such as the

National Federation of Music Clubs and the Musicians Emergency Fund organized

volunteers for the purposes of playing in military hospitals” (Vest, 2020, p. 125). Due to

the vigorous efforts of many devoted physicians and musicians during World War II and

its aftereffects, the healing powers of music were observed on an exceptional scale

(Rorke, 1996). In 1942, a Music Advisory Council of the Joint Army and the Navy was

18

initiated by the Secretaries of War and the Navy to coordinate recreational and education

programs within the armed forces. This council, made up of civilian and military

personnel, met to advise the armed forces in the development of such music programs for

the convalescing soldiers in hospitals (Sullivan, 2007). In a work published in 1966,

Helbig, wrote that the U.S. Surgeon General in October of 1943 sensed “the significance

of music in the lives of soldiers” (p. 29) and therefore, “directed that consideration be

given to music as an integral part of the recondition program [of injured soldiers]” (p.

31).

A 1945 War Department document stated the following regarding the use of

music with the injured soldiers:

Music should be provided along with other activities offered to patients because it

is one of the most effective vehicles for bringing a group together, for releasing

the emotions and for creating a spirit of fellowship and esprit de corps. If he

simply listens to music, his interests are broadened, and his sense of well-being is

generally increased. (Sullivan, 2007, p. 288)

Music was used in the treatment of those with traumatic brain injuries,

neurological conditions, diseases, and battle fatigue, later termed posttraumatic stress

disorder (Foran, 2009).

The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

(American Psychiatric Association, 2013), defines PTSD as made up of four clusters of

symptoms including invasive and repeated memories of the trauma, escape of trauma

related stimuli, numbing and/or obstructive changes in mood or cognitions relating to the

trauma, and changes in responsiveness and arousal. Thousands of military personnel

19

required medical and psychological care following World War II. Recovering personnel

required prolonged medical care and the military recognized the need for recreational

services to sustain morale and emotional well-being. This created a situation in which

music in hospitals could become more commonplace and the effects of music

investigated. This was the impetus that led individuals to investigate the use of music as

a therapeutic modality and the formation of music therapy as an organized profession

(Robb, 1999).

Social Aspect

Socialization, which can be defined as the action of creating and prolonging

relationships, allows individuals to develop the expertise necessary for social competence

(Gooding, 2010). Research has suggested that an absence of social competence makes it

arduous to develop positive relationships with peers and teachers in elementary school

(Visvaldas Legkauskas, 2019). According to a recent study conducted by (Visvaldas

Legkauskas, 2019), social competence had made a notable offering towards the

differences of each school adjustment indicator appraised in the present study, including

academic achievement, participation in bullying, and student-teacher relationship. Even,

interpersonal, and learning-related characteristics of social competence exhibited

different patterns of links to school adaptation indicators.

These struggles tend to evolve into long-term adjustment issues, including lower

academic achievement, skipping classes, substance abuse, unruly behavior, and mental

health issues in adolescence and further on (McClelland, Acock, & Morrison, 2006). A

study on the influence of social interaction on student learning divulged that students

learned from others, thus intensifying comprehension and retention by activating prior

20

knowledge, making connections, and synthesizing new ideas; social interaction generated

a positive working environment; and social interaction supplied a means for students to

view topics from various perspectives and strengthen their critical thinking and problem-

solving skills (Hurst et al., 2013).

“The potential for music programs to promote psychosocial wellbeing in

mainstream schools is recognized in both policy and research literature” (Crooke &

McFerran, 2014, p. 14). A study conducted by (Pasiali & Clark, 2018) indicated that

music therapy has the probability of being an effective intervention for promoting social

competence of school-aged children with insubstantial resources, specifically in the areas

of communication and low-performance/high-risk behaviors. Music therapy researchers

choosing development of social skills and overall well-being with adolescents found

advancements in communication skills, attitudes toward learning, and relationships with

peers (Porter et al., 2017).

Physical Rehabilitation

Physical rehabilitation requires intensive physical, emotional, and cognitive effort

from the patient. Current and traditional methods of reclamation have been effective in

providing virtuous interventions to build up the patient’s motor potential (Weller &

Baker, 2011).

In 1937, the American Medical Association acknowledged the American

Congress of Physical Therapy as a medical specialty society, followed by the inception of

the American Registry of Physical Therapy Technicians, and the creation of a board of

certification (Scappaticci, 1998). The recognition of physical therapy as a medical

specialty, and the subsequent development of the board of certification led to the ability

21

to fund research and development in the field of physical therapy, allowing new and

innovative ways to add comfort and independence to those suffering from physical

ailments.

Despite the lack of published research on the subject, the idea of using music to

engage a patient during therapy may be of interest to pediatric clinicians who may

have noticed that singing to children or playing music during the session may help

stimulate movement in a ‘passive’ child, interest a patient resisting therapy, or

comfort a crying baby. (Rahlin, Cech, Rheault, & Stoecker, 2007, p. 106)

Infants cry for many reasons including physical discomfort, emotional stress, hunger, and

social anxiety. If music has a positive ramification on the child’s emotional state, this

may lead to enhanced participation in therapeutic course of action and potentially, an

expanded rate of patient progress. Also, if the child cries less, parent gratification with

the therapy services could consequently improve (Rahlin et al., 2007).

Bruscia (1989) stated that music is put in to practice during the therapeutic

process either as the “primary agent” of change, in which the music has a direct effect on

the client, or as the facilitating agent, which supplements the therapeutic relationship and

leads to change. In rehabilitation medicine, music is used both as the primary agent of

change and as a facilitator. For example, music is considered a primary agent when used

to prompt and control pacing of physical exercise (i.e. determine the tempo of exercise

repetitions), and considered a facilitating agent when used to inspire discussion of socio-

emotional affairs related to disability or injury (Scappaticci, 1998).

22

Treatment of Depression

In 1998, the American Association for Music Therapy was formed to help combat

the issue of depression. According to a study conducted by Feng et al. (2019) there are

two fundamental methods of music therapy when dealing with depression. The creative

process requires the patient to sing, or play the music themselves, whereas the receptive

method allows the subject to listen to the music already created. This study showed that

music therapy has a significant effect on brain function in both the study group diagnosed

with major depressive disorder, as well as the control group.

National Institute of Mental Health (2018) states that depression is a common but

serious mood disorder. The institute indicates that depression causes severe symptoms

that affect how individuals feel, think, work, and handle daily activities. In an

operational sense, depression is also defined as the medical illness experienced by

individuals who meet necessary criteria as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory

(Burak & Atabek, 2019). Morrison and O’Conner (2005) suggests that depression poses

a greater danger to adolescents than to adults and more than 50% of university students

report depressive symptoms after starting their studies.

In a 10-week music therapy intervention conducted by Chen, Chen, Ho, and Lee

(2019), music therapy reduced depression among early adolescents with high pre-test

scores, based on the Beck Depression Inventory, although adolescents with low pre-test

scores were not affected. This result indicates that music therapy has a greater effect on

adolescents with severe depression more so than adolescents with mild depression. In a

separate study conducted by Aalbers et al. (2020), nine out of 11 students reported

reliable improvement in depression symptoms at post-test and four-week follow-up.

23

Treatment of Anxiety

“Anxiety is a state of utmost concern and fear that a person experiences when

he/she comes in contact with a stimulus from the outside or inner world and individual

has trouble in preventing negative physical, emotional and mental reactions” (Sargin,

2009, p. 1414). These reactions start at birth as the individual receives stimuli from the

surrounding social environment and culture. These reactions, whether positive or

negative, play a large part in the abilities of the individuals to grow their emotional

experiences and to adapt or be overwhelmed by the anxiety that comes with these

reactions.

According to Egenti et al. (2019), social anxiety is a continuous fear of situations,

and it is considered a common psychological disorder that occurs as the individuals

develop and grow, causing significant impairments to social functioning and could cause

a deficit in social skills practice. These impairments could cause long-term negative

impacts on academic performance, psychological well-being, and inter-personal

relationships. There could also be a significant impact on the individual’s ability to cope

with their environment, leading to disruptive behavior and learning disorders. Egenti et

al. also believes that it is possible that music therapy, along with cognitive behavioral

therapy intervention can help lessen social anxiety among socially concerned schooling

adolescents.

Kwok (2018), devised a study to investigate the efficacy of a design protocol,

integrating positive psychology and components of music therapy, in increasing the

optimism and enhancing emotional competence, hence reducing anxiety, and amplifying

subjective happiness of the adolescents with anxiety symptoms. Kwok used resource-

24

oriented music therapy, merging positive psychology and music therapy. The goals are

to help recognize, become acquainted with, and express their emotions, and remain

interested in and be encouraged to pursue goal oriented activities. The study shows a

notable decrease in anxiety symptoms when compared to the control group. Results

showed that students in the experimental group had greater hope, emotional competence,

happiness, and less anxiety symptoms than those of the control group.

A music therapist described the case of a 13-year-old rape victim who had low

intellectual functioning and post-traumatic stress disorder. Five sessions of music

therapy, that encouraged her to improvise music, caused her confidence to increase and

helped her better control her extreme anxiety (Henderson, 1996).

In a study conducted by Millett and Gooding (2018), 40 pediatric patient and

caregiver duos undergoing ambulatory surgery were studied to compare and control the

effects of active and passive distraction-based music therapy interventions. Preoperative

anxiety in the pediatric patients was measured pre- and post-intervention using the

modified Yale Pediatric Anxiety Scale, while caregiver anxiety was measured through

self-reporting using the short-form Strait-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y6. The groups

receiving active or passive interventions were selected at random. The outcome showed

that the two groups had a significant level of anxiety reduction, with neither intervention

having a significant effectiveness over the other intervention strategy. A second study

using active and passive music therapy was designed and aimed to know the efficacy of

counseling group fulfillment of cognitive behavior therapy approach in reducing

academic anxiety among millennial students. Pretest versus posttest showed passive

music therapy techniques showed more promise than active, where posttest vs follow-up

25

showed that active was more effective after two weeks of therapy (Situmorang et al.,

2018).

Treatment of Stress

“Stress impedes the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and

the sympathetic nervous system, which notoriously escalates concentrations of the stress

hormone cortisol” (Fallon et al., 2020, p. 20). Stress has long earned a reputation of

causing harm to the physical, emotional, and social well-being of individuals. Stress has

also become a leading cause of immunosuppressive disorders. Short-term stress is

believed to be an immunoprotected device which enhances the fight or flight response

while long-term stress causes the body to decrease its ability to produce adaptive immune

responses (Dhabhar, 2014).

Children exposed to a buildup of stressful life events within a proportionately

short time span are at risk for behavioral and academic difficulties (Tisak, 1989). Stress

can also lead to an increased risk of diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular

disease if left untreated. According to the American Institute of Stress (2012), stress is

the number one health threat to Americans (as cited in Ferrer et al., 2012). Additionally,

if adequate coping skills are lacking, a somatic or psychological dysfunction may be

expressed in the form of persistent pain and illness, gastrointestinal distress, sleep

disturbances, fatigue, high blood pressure, headaches, or stress emotions, such as anger,

anxiety and panic, fright, guilt, shame, sadness, and depression (Yehuda, 2011).

Studies show that music therapy can decrease the amount of salivary α-amylase

(sAA), which is a time and fiscal effective measure of stress in individuals with ASD. A

study conducted by Poquerusse et al. (2018) showed that music therapy consisting of 50-

26

minute group interactivity and discussion associated to emotions when listening to

composed music, and group-based music ad-libbing with music instruments significantly

decreased baseline sAA levels in students with ASD.

A separate study examining the effects of music therapy on stress and pain control

was conducted to gather the discernment of staff members on the efficacy of music

therapy in hospital emergency departments. During the three-year study over 1,500

patients were engaged in music therapy including music-assisted relaxation, therapeutic

listening and musical requests, musical deviation, song writing, and therapeutic singing.

Significant improvements were seen in both stress and pain for music therapy patients. A

staff questionnaire showed that 92% of respondents would be likely to recommend music

therapy sessions for future patients to reduce pain and stress, and 80% indicated that the

music therapist’s practice improved their caregiving experience (Mandel, Davis, & Secic,

2019).

A study developed and conducted at the Salisbury University suggests that

listening to music has a greater positive effect on stress reduction than that of music

improvisation. This study consisted of 105 participants completing a stressor task and

then being appointed to one of three groups: (a) control group, (b) music listening group,

or (c) music improvisation group (Fallon et al., 2020). The changes in measurements

between the baseline sessions and the post-stressor sessions showed an increase in

irritation and distraction confirming the stressor task to be successful. There was also a

significant change from the stressor to recover sessions in the music listening group, but

no significant change in the music improvisation or control groups during this same

timeframe (Fallon et al., 2020).

27

Contemporary Perspective of Music Therapy

Music therapy in today’s scientific domain is developing as an integrative

discipline that picks up its methodological principles in holistic approaches to the

individual and his sufferings in philosophy, cultural anthropology, and

psychology, finding ways of producing results and discovering rehabilitative

mechanisms in the practice of restorative medicine in combination with the

methods of musical education and psychology. (Toropova & L’vova, 2018, p. 53)

To understand how music can be used in the K-4th grade special education

classroom, we looked at way’s music was used in therapy. Many different types of

therapy use music as a tool for improvement, from cognitive to physical, emotional, and

social. Music therapy contains elements of a “meaningful and flexible treatment”

modality, as music experiences are characteristically structured, yet creative. Many

children react positively to music encounters, potentially increasing engagement for

learning (LaGasse, 2014). “Studies show music therapy to promote improvement of

clinical and social status in preterm newborns, improving, among other conditions, heart

and respiratory rate, level of oxygen saturation, decreasing crying episodes, and thus,

promoting quality of sleep” (Moran et al., 2015, p. 177).

The diagnoses covered by music therapy ranges from disabilities caused by (a)

physical and neurological trauma (amputations, burns, brain injury, spinal cord injury,

hip dislocation, coma, fractures, orthopedic impairments); (b) specific illnesses and

conditions (arthritis, asthma, epilepsy, poliomyelitis, hemophilia, tension headache); (c)

congenital developmental diagnoses (autism, cerebral palsy, learning disorders, scoliosis,

spina bifida, visual impairments); and (d) degenerative diseases (e.g., dementia,

28

Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease) (Weller & Baker, 2011).

Music therapy has been employed for people with many different mental health

problems, including anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, dementia, schizophrenia,

autism, trauma-induced disorders, substance use disorders, and learning disabilities,

(Paul, Lotter, & van Staden, 2020).

In 2011, a master’s thesis administered by a board-certified music therapist

explored the effect of live music therapy on 30 adult emergency room patients and found

a notable self-reported decrease in pain and a remarkable increase in comfort, calculated

through visual analog scales for pre/post comparison. The thesis also reported that all of

the patients suggested that they would request music therapy services if admitted to the

emergency room again (Mandel et al., 2019).

Cognitive Development

According to the “temporal opportunity” conception of environmental stimulation

during brain development, encounters in childhood and adolescence are important to

many abilities in adult life, which makes the choice of what education to supply to a child

a serious matter. Although many longitudinal developmental studies of music education

incorporate a well-matched control group, such as an arts program, there is only little

research contrasting instrumental training in childhood with dance or sports, which could

offer engrossing avenues in pliability research and aid the parents in making a well

informed decision. Thus, although all arts and sports programs do have gratifying effects

on cognitive development, instrumental musical training appears distinctive in the wide

array of observed long-term effects (Miendlarzewska & Trost, 2013).

29

Training to play an instrument is a multisensory motor experience. Studies have

shown that music influences cognitive development and the earlier the introduction of

music, the better the effects. Some studies have also shown that the type of music

instruction also influences the type of cognitive development taking place. One study

found that nine-year-old children given piano instructions scored higher than the control

groups on spatial-temporal tasks immediately after the instructions was given. There was

no difference noted after a two-year hiatus from the instruction (Rauscher, 2003). A

follow-up study showed that participants who received music instruction before age five

scored appreciably higher than those who did not receive instruction. A final study

showed that children who received keyboard instruction starting at age three, and

continued for two years, scored higher on spatial-temporal and arithmetic tasks two years

after instruction had ended (Rauscher, 2003).

A study conducted on the effects of music training on the brain and cognitive

development of underprivileged children, ages three to five showed powerful and

remarkable improvements in non-verbal IQ and numeracy and spatial cognition (Schlaug,

Norton, Overy, & Winner, 2005). The extent and improvements were indistinguishable

in the children receiving music training, attention training, and consistent Head Start

instruction in smaller class settings advocating that the size of the class and amount of

attention being given to each child may be a fundamental factor in the cognitive

development.

A separate study facilitated by the University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

showed that “children who experience musical training have better verbal memory,

second language pronunciation accuracy, reading ability and executive functions”

30

(Miendlarzewska & Trost, 2013, p. 1). It was concluded that musical training uniquely

engenders near and far transfer effects, developing a foundation for a gamut of skills, and

thus promoting cognitive development (Miendlarzewska & Trost, 2013).

Cognitive rehabilitation is important after a TBI to ensure that the patient is

allowed to recover as well as possible. According to Bower, Catroppa, Grocke, and

Shoemark (2014) TBI is the number one cause of death and acquired affliction in