Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

School Board Accountability, Evaluation, and Eectiveness

Report

© 2023 National School Boards Association, All Rights Reserved

Table of Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 4

Part I — Ten Thousand Democracies: Statistics and Facts about School Districts and School Boards ............. 6

School Board Size ........................................................................................................................................................... 7

Elected vs. Appointed School Board Members ........................................................................................................... 8

Turnover and Retention of School Board Members ................................................................................................... 9

Time Spent on School Board Services ....................................................................................................................... 10

Compensation for School Board Members ................................................................................................................ 11

Professional Development of School Board Members .............................................................................................. 12

Part II — One Common Goal: Every Student’s Success .......................................................................................... 17

NAEP Basic vs. Procient .............................................................................................................................................. 17

Reaching the Basic Achievement Level: Why It Matters ................................................................................................. 18

Helping All Students to Reach Prociency in Reading and Math .......................................................................... 20

Increasing Graduation Rate and Raising the Graduation Bar ............................................................................... 23

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 1: Pathways to Postsecondary Success .............................................................. 27

Part III — School Board Accountability, Eectiveness, and Evaluation ................................................................ 28

School Board Accountability and Democracy ............................................................................................................... 28

What Research Says About School Board Accountability and Student Achievement ................................................. 29

© 2023 National School Boards Association, All Rights Reserved

Table of Contents

States’ Requirements for School Accountability .......................................................................................................... 29

How Districts Describe School Board Accountability ....................................................................................................... 30

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 2: Has School Board Governance Been “Hijacked?” ........................................... 32

School Board Eective Governance: A Key to High Achievement for All Students ................................................. 34

Empirical Research on Characteristics of Eective School Boards and Student Achievement ........................... 34

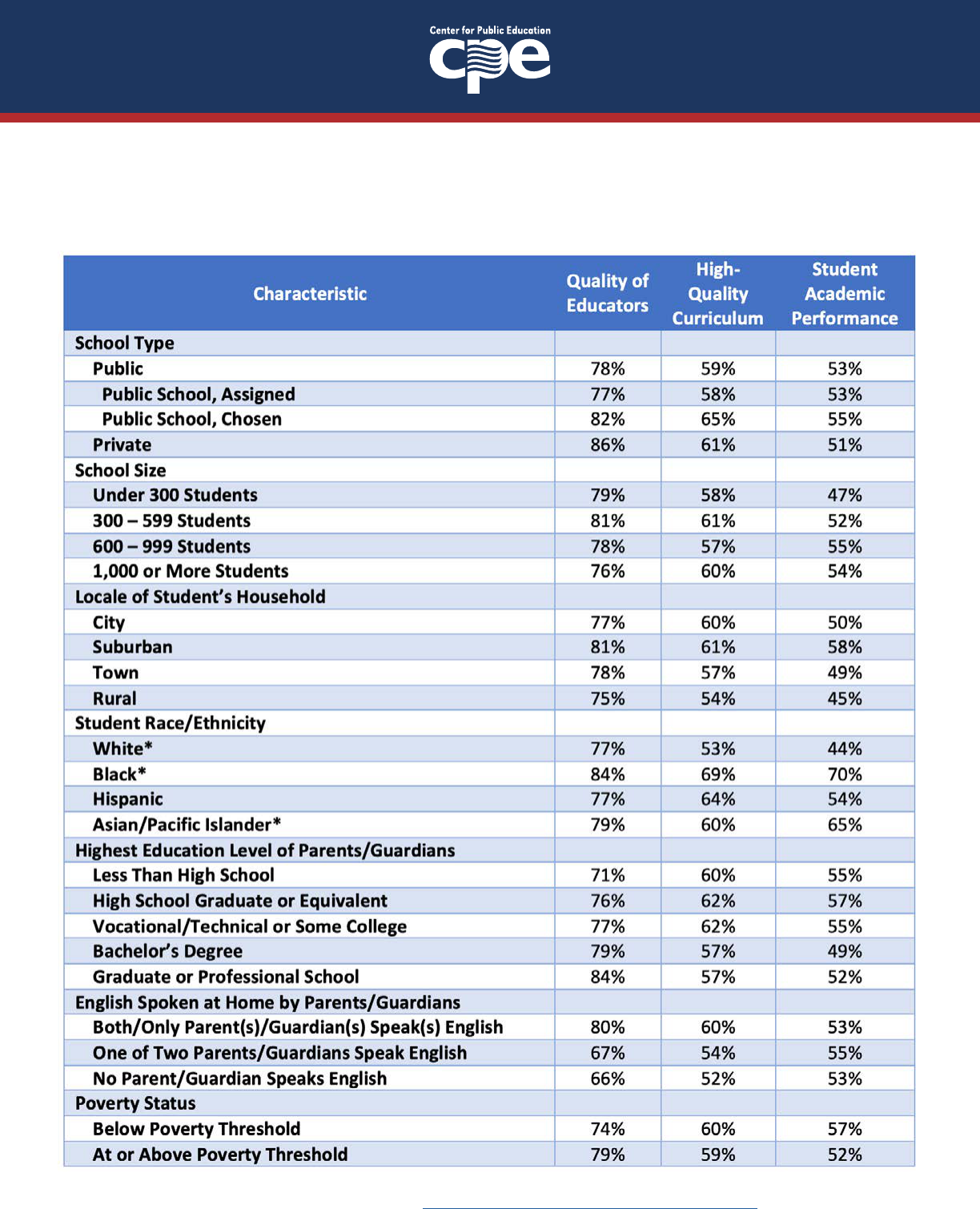

What Parents Want Regarding Student Achievement ............................................................................................ 35

How School Boards Address Eective Governance and Student Achievement ................................................. 38

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 3: Examples of School Districts Practicing Eective Governance ........................ 39

School Board Evaluation: Measuring Eectiveness to Improve Governance .......................................................... 41

Why School Boards Need Self-Evaluation .................................................................................................................... 41

What Evaluation Tools School Districts Are Using ........................................................................................................ 42

A Lack of Recent Research on School Board Evaluation and Eectiveness ............................................................... 43

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 4: Post-Evaluation Actions of School Boards ...................................................... 45

Conclusions — Governance Matters ....................................................................................................................... 47

Technical Notes ......................................................................................................................................................... 48

References ................................................................................................................................................................. 49

4

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Introduction

In the United States, most students attend a public school in a district overseen by a democratically elected

school board. In political science, school boards are oen portrayed as ten thousand democracies (Berkman and

Plutzer, 2005). School board members are oen described as “citizens-policymakers” because they “constitute a

middle ground between normal citizens and professionalized policymakers ― with large variations based on the

size of the districts and the model of selection” (Asen, 2015; Delevoye, 2020).

School board members have been regarded as one of the largest groups of policymakers in the U.S. (Delevoye,

2020). Fostering an educational environment in which every student reaches a high achievement level and

successful postsecondary life is a common goal of all local school boards. In education research, school board

accountability, eective governance, and board evaluation are all relevant to this common goal. An important

characteristic of eective school boards is “accountability driven, spending less time on operational issues and

more time focused on policies to improve student achievement” (Dervarics and O’Brien, 2011).

Media reports on American public schools have been dismal for decades. e COVID-19 pandemic increased

the perception that many American schools are failing to prepare students for the future (Jimenez, 2022;

Tripses et al., 2015). e 2022 results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) show dramatic

and sobering declines in math and reading scores for the nation’s fourth- and eighth-graders. Some researchers

report that, historically, school boards have not focused to any great extent on student achievement (Tripses et

al., 2015). For example,

• Dating back to the early 1700s, the main role and function of school boards was to hire the head schoolmaster and oversee the maintenance

of the school building (Tripses et al., 2015).

• A study conducted in West Virginia (McCall, 1997) found that school boards spent 3% of their time on policy development and as much as

54% on administrative matters.

• Researchers conducted a study of 55 randomly selected school boards and found that “nancial and personnel issues were among the

most frequent areas of decision-making, displacing deliberations on educational policy by a signicant margin” (Beckham and Wills, n.d.).

The authors observed that school boards often play a quasi-judicial role instead of placing policymaking as the board’s priority, and “many

local boards act as hearing agencies for employee and student grievances.” It has been recommended that school districts delegate the

responsibility to hear complaints and appeals from individual students or employees to administrative law judges or other qualied third

parties.

e context of highlighting student achievement as a key accountability of school boards can probably be traced

back to the 1983 publication of “A Nation at Risk.” e report by the National Commission on Excellence in

Education caused a dramatic escalation of national concern about public education. Since then, state and federal

policymakers have been intensively requiring rigorous testing, higher graduation rates/requirements, and higher

academic standards (Tripses et al., 2015). In 2002, Congress passed the law No Child Le Behind (NCLB, 2002),

which increased pressure on school boards and superintendents to be more accountable for student achievement

(Dervarics and O’Brien, 2011; Sell, 2006).

5

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Introduction

“Public displays of test scores, mandated by the law, have engaged communities to some extent in the process

of evaluating performance of both school boards and superintendents” (Tripses et al., 2015). At the same time,

the student achievement gap has become an increasing concern for educational equity. More studies suggest

that school boards can and do inuence academic outcomes, and improving school board governance is viewed

as a legitimate approach to improving academic achievement (Eadens et al., 2020; Ford, 2013; Land, 2002;

Shober and Hartney, 2014).

To inform school leaders of some of the current challenges and potential solutions to improve education

leadership, the Center for Public Education (CPE) of the National School Boards Association (NSBA) compiled

this research report. ere are three parts to this report. In Part I, we present readers with statistics about school

districts and school boards that show the diverse nature of the education system across the country. In Part II, we

share the recent NAEP data to help readers understand the urgent call for education leaders to improve student

achievement. Part III will focus on what research says about the following three discussion issues:

1. The connection between student achievement and school board accountability.

2. The association between eective governance and student achievement.

3. The relationship between board eectiveness and evaluation.

6

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Part I

Ten Thousand Democracies: Statistics and Facts about School

Districts and School Boards

In the 2020-21 school year (SY), 19,254 operating public school districts served 49,356,945 students, according

to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Operating schools/districts include all those providing

services for prekindergarten through grade 13 as of the start of the reported school year. Figure 1 and Table 1

show that there are signicant dierences between states in the total number of school districts operating and the

total number of students served in public schools. For example,

• California has more than 2,000 school districts. Texas, Illinois, Ohio, and New York have more than 1,000 school districts, respectively.

• States with more school districts often have larger student populations. More than 6 million students attend public schools in California.

More than 5 million students go to public schools in Texas. More than 2.6 million students are served in public schools in New York.

• However, states with fewer school districts do not necessarily serve a small student population. For instance, in Maryland, 25 school districts

serve nearly 900,000 students. In Florida, 77 school districts serve nearly 2.8 million students.

• By the same token, states with smaller student populations may have relatively more school districts. For instance, in Vermont, about

83,000 students are distributed among 184 school districts; in North Dakota, there are about 115,000 students and 221 school districts; in

Montana, about 146,000 students attend 483 school districts.

Figure 1. Number of School Districts by State

Source: Table 2. Number of operating public schools and districts, student membership, teachers, and pupil/teacher ratio, by

state or jurisdiction:<br /> School year 2020–21 (ed.gov)

7

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

School Board Size

Dierences in school districts in the U.S. oen lead to diverse structures and styles of governance of the school

boards. Ballotpedia, a non-prot organization that collects information on elections, politics, and policy, reports

that at the start of the 2022-23 school year, there were 82,423 school board members in 13,194 school districts.

According to Ballotpedia, those school districts feature school board member information on the district’s

website or other online platforms.

Figure 2 shows that among the 13,194 school districts in the country, 85% have ve to eight school board

members. In fact, most district boards are composed of either ve or seven members.

• Only 495 boards have six members, and only 86 have eight members.

• About 2% or 243 districts across 18 states are governed by school boards with more than 10 members.

• The number of elected school board members per state ranges from nine in Hawaii (which has one statewide school district) to 6,994 in

Texas (representing more than 1,000 school districts).

• The average number of school board members per district ranges from 3.45 in West Virginia to 9.97 in Connecticut.

Table 1. Number of School Districts and Number of Students, by State: SY 2020-21

Source: Table 2. Number of operating public schools and districts, student membership, teachers, and pupil/teacher ratio, by

state or jurisdiction:<br /> School year 2020–21 (ed.gov)

8

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Elected vs. Appointed School Board Members

Approximately 90% of school board members are elected. According to a 2002 report on American school

board compositions, about 93% of school boards are elected rather than appointed (Hess, 2014). In 2018, NSBA

surveyed school board members and found that among the 2018 respondents, the majority (88%) were locally

elected.

e NSBA report also indicated that the number of appointed board members among the 2018 respondents

more than doubled from 2010 (12% versus 5.5%). Some researchers suggest that usually, the catalyst for moving

to an appointed school board system is “the elected board’s mismanagement causing poor student performance,

nancial crises, teacher shortages or inghting with the superintendent” (Llamas , 2020; Milliard, 2015). It

should be noted that each school district has unique challenges, and changes about how to form the board are

oen based on decisions from state or local-level governing bodies.

• In 2021, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D) signed House Bill 2908, which expands the Chicago Public Schools Board of Education to 21 members

beginning in 2025. Voters will elect 10 members, and the mayor will appoint the other 11. In 2026, all members of the board will be elected

(Tabor, 2023).

• Unlike most localities in Virginia, Hanover County remains one of the few jurisdictions in which the local governing body appoints members

to the school board (German, 2023).

• In Pennsylvania, the Butler Area School Board approved appointing two candidates to ll the seats vacated by resigning board members. The

two newly appointed school board members have been in the top ve of those receiving votes in the primary election, and will “have a good

chance of being elected to continue for a full term” this fall (Friel, 2023).

Figure 2. Number and Percentage of School Districts, by Board Size: 2022

Source: Analysis of school district and board member characteristics, 2022 - Ballotpedia

9

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

“While school boards are a quintessential example of representative democracy, many districts experience low

participation by both candidates and voters” (Cai, 2020). While voter turnout for political oce elections has

increased since 2014, in local school board elections, voter turnout has been discouragingly low — oen just

5% to 10% (Cai, 2020). At the same time, according to Ballotpedia (2023), approximately 2.03 candidates are

running for each seat in the 1,428 school board races in 2023, which is 11.4% less than in 2021 (2.29 candidates

per seat).

Turnover and Retention of School Board Members

Researchers suggest that student achievement is correlated with two sources of social capital of school boards,

namely internal and external ties. Internal ties refer to the bonding of members within a school board; external

ties can be conceptualized as the bridging between board members and all other stakeholders (Saatcioglu et al.,

2011). Data from 175 Pennsylvania districts between 2004–05 and 2006–07 school years show that these two

sources of social capital are positively associated with nancial and academic outcomes at the district level.

Bonding and bridge-building within a school board oen require time. Alsbury (2008) found “student test score

decline as board turnover increased, particularly in smaller districts and when delineating politically motivated

board turnover.” Additionally, school boards have to overcome the challenge that many board members serve

terms of two to four years, and turnover is unavoidable (Korelich and Maxwell, 2015).

NSBA data show that, on average, board members who responded to the 2018 survey served 8.6 years on

their boards. In many cases, school board members end their service terms subjectively. According to a study

conducted by School Board Partners, a nonprot group that trains new school board members, in 2016, more

than 70% of school board members planned to pursue another term on the board; in 2022, only 38% of current

school board members planned to run for reelection (Merod, 2022).

Unfortunately, we did not nd data about how many school board members resign each year. Anecdotal reports

show that there seems to be an increase in the resignation of school board members, but it is unclear to what

extent the early exit of board members aects student achievement. For instance,

• In Oregon, Zaitz (4/25/2023) reported that a school board was out of business after ve of its seven members quit amid growing concern

about a new ethics requirement. “Until the seats are lled, those school districts don’t have governing boards to consider budgets, approve

contracts or consider hiring.”

• In Connecticut, Ryser (5/31/2023) reported that two school board members in a district have resigned amid a battle over two ‘sexually

explicit’ books that a committee has recommended keeping on the library shelves. The school board chairperson said, “Their energy,

tenaciousness, team spirit, and constructive contributions to our discussions will be sorely missed.”

• In Colorado, Grimes (3/13/2023) reported that three board members in a school district resigned, and only two members remained on the

board. The superintendent stated, “It is always disappointing when adult issues impact a school district and keep it from focusing on the

most important work — ensuring our students receive the best education possible.”

10

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Another way to cut short a board member’s term is through school board recalls. School board recalls are the

process of removing a member or members of a school board from oce through a petitioned election instead

of during a regularly scheduled election. “Bad behavior, mismanagement of funds, conicts with district

administrators or teachers, refusing to listen to their constituents, and violating open meetings laws are some

of the reasons listed on petitions seeking to recall school board members” (Ballotpedia, 2023). According to

Ballotpedia (2023), on average, there were 34 recall eorts involving about 80 school board members each year

between 2009 and 2022.

Time Spent on School Board Services

More than half of school board members (52%) reported that their entire school board meets twice per month,

while 43% said the entire board meets only once a month, according to the 2018 NSBA study. It should be noted

that board members oen engage in other activities that add hours to their board service. “It’s not atypical that

a large-district school board member would work about 40 hours a month on board-related duties” (Great

Schools, 2022).

• “Serving on a local school board requires lots of it. No longer is it reasonable to expect board service to take one night per month. Public

education has become far too complex and community expectations far too great, for the leisurely pace of yesteryear to be the rule today.

Today’s board members say they can easily spend 30 or more hours per month on school issues: negotiating contracts, planning, work

sessions, community meetings ― not to mention personal phone calls and other contacts made.” (The Association of Alaska School Boards,

n.d.)

• “Years ago, when the role of the board member was perceived more as a ‘trustee’ the current legal requirement of holding at least one

regular board meeting per calendar month may have been realistic. Today, however, most boards hold more than one meeting per month

with some holding weekly meetings. These may include Regular Board Meetings; Special or Emergency Board Meetings; Work Study

Sessions - open meetings with sta (issues, reports, etc.); Public Input Meetings - no decisions, only public comment; Judicial Hearings

- grievance/discipline matters; Planning Retreats, and so on. Individual board members will also be involved with Board Committees and

certain advisory committees, spending hours on the phone with constituents, some of which will undoubtedly be employees and reading all

the materials in preparation of meetings. Board members can easily spend 15 hours per week on Board-related business.” (The New Mexico

School Board Candidate Manual, 2021)

• “Today’s board members say they spend an average of 45 hours each month on board work. This estimate may increase each year because

of the changing nature of our society and its schools.” At the same time, a discouraging phenomenon has often been that “being a school

board member may seem like a thankless job – struggling with complex problems for long hours and taking criticism when things don’t go

right.” (The Colorado Association of School Boards, 2022)

11

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Compensation for School Board Members

According to the NSBA report, most board members (61%) in 2018 were volunteers who received no annual

salary for their board service. is remained comparable to the 2010 survey data when 62.3% indicated

no annual compensation. In addition, 73% of the 2018 respondents indicated they received no stipend for

individual meetings, just slightly less than the 76.5% who responded to that same question in 2010.

In January 2021, we examined state policies regarding how the services of school board members are

compensated. We found that among 50 states, approximately:

• Seventeen states (34%) do not pay school board members, although some of the states may pay travel expenses or training fees for board

members.

• Thirteen states (26%) compensate school board members with limited amounts based on their participation in board activities, such as

board meetings or traveling for training or conferences.

• Eleven states (22%) do not have any specic legislation for compensating school board members. In some of the states, school board

members are not paid at all, while in other states, board members may be paid by certain decisions made by municipal or county

governments.

• Only six states (12%) have state statutes that dene annual salary or compensation for board members.

• Nevada and California compensate school board members based on their county or school district population.

12

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Professional Development of School Board Members

As we mentioned above, most board members serve limited terms, which is the nature of a democratic system.

Since turnover is unavoidable, training for newly elected board members becomes a necessity (Korelich and

Maxwell, 2015; Zion, 2008). Data from NSBA show that most school board members receive training aer being

elected. In 2018, 81% of the surveyed school board members reported that they had received training from their

state school boards association, followed by 57% who had received training from their board or district and

47% from NSBA. Compared with 2010, more board members reported receiving training or participating in

professional development. It is unclear whether such training is required or optional for school board members.

With respect to training content, most school board members (78%) reported that they had training about board

roles, responsibilities, and operations; more than half (56%) said that they had training in funding and budget

issues. In the same survey, school board members were asked what new or additional training they would like to

receive. More than half (51%) said that they wanted more training on student achievement issues.

We examined the states that have laws in place to require school board members to participate in professional

development aer being elected (Table 2). In 22 states, there is clear statutory language addressing training

requirements (e.g., the amount of training time and the topics of training content) for school board members. In

several states, board members are required to attend training focusing on student achievement. For example,

• New Jersey ― In 2007, the state’s School District Accountability Act was signed into law. “This multi-faceted legislation impacts school

boards/charter school trustees in a variety of ways and one key area is board member/trustee training,” according to the New Jersey School

Boards Association (NJSBA). One of the mandated training programs provided by NJSBA is focused on student achievement.

• Texas ― School board members are required to participate in training on “Evaluating and Improving Student Outcomes” for three hours

within the rst 120 days in oce and three hours every two years.

• Louisiana ― If a school district is deemed “academically unacceptable or in need of academic assistance” by the state board, school board

members must participate in training on student achievement and school improvement at least two hours annually (Erwin, 2022).

13

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Figure 2. Number and Percentage of School Districts, by Board Size: 2022

State Training Requirement Source

Alabama

The Governance Act outlines specic training requirements for all city and county school

board members in Alabama. Local school board members must take a school board member

orientation that covers certain topics, and must earn 6 hours of training every year.

AASB

Arkansas

The state requires a local school district board member to obtain no less than 6 hours of

training and instruction each calendar year. Members elected for an initial or non-continuous

term are required to meet additional training opportunities during their tenure.

ECS

Florida

The state-required training for school board members is 4 hours of training on ethics that ad-

dresses Article II, Section 8 of the Florida Constitution, the Code of Ethics for Public Ocers

and Employees, and the Government-in-the-Sunshine provisions in Chapters 119 and 286

relating to public records laws and public meeting laws.

FSBA

Georgia

The state requires the state board of education in the department of education to craft and

oversee local school board member training. In 2009, the state board of education convened

a task force to, among other things, develop and recommend standards for local school

boards and guidelines for member training. The task force established a new lexicon around

central themes to reect local education priorities and maintain student achievement. The

themes identied in the state standards for local education boards include governance struc-

ture, strategic planning, board and community relations, policy development, board meetings,

personnel, nancial governance, and ethics. The state standards may include an expectation

on knowledge, skill, or performance. If the state designates a high-risk school within the local

board of education’s purview, the members must complete additional training.

ECS

Illinois

The state requires that each voting member of a school board must complete 4 hours of pro-

fessional development training within the rst year of their rst term. Topics of the training

must include nancial oversight and accountability, labor law, and duciary responsibilities of

a school board member.

ECS

IASB

Kentucky

The annual in-service training requirements for all school board members in oce as of

December 31, 2014, shall be (a) 12 hours for school board members with zero to 3 years of

experience; (b) 8 hours for school board members with 4 to 7 years of experience; and (c) 4

hours for school board members with 8 or more years of experience. The Kentucky Board of

Education shall identify the criteria for fullling this requirement. For all board members who

begin their initial service on or after January 1, 2015, the annual in-service training require-

ments shall be 12 hours for school board members with zero to 8 years of experience, and 8

hours for school board members with more than 8 years of experience.

KY

Louisiana

The state requires each local public school board member to receive a minimum of 16 hours

of training and instruction during the rst year of service on the board to receive the “Dis-

tinguished School Board Member” designation. Each member must receive a minimum of 6

hours of training and instruction annually beyond the rst-year requirements. The training

topics currently include state school laws, governing the powers, duties, and responsibilities

and educational trends, research, and policy. The Louisiana School Board Association pro-

vides the training programs.

ECS

LA

14

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

State Training Requirement Source

Minnesota

A member shall receive training in school nance and management developed in consulta-

tion with the Minnesota School Boards Association and consistent with section 127A.19. The

School Boards Association must make available to each newly elected school board member

training in school nance and management consistent with section 127A.19 within 180 days

of that member taking oce. The program shall be developed in consultation with the depart-

ment and appropriate representatives of higher education.

MN

Mississippi

The state law says that “Each school board member shall be required to le annually in the

oce of the school board a certicate of completion of a course of continuing education

conducted by the Mississippi School Boards Association.”

ECS

MSBA

Missouri

The state law, The Outstanding Schools Act of 1993, requires that all new school board

members have at least 16 hours of orientation and training within one year of their election or

appointment.

MARE

Nevada

The state implemented training requirements in 2016. In the rst and third year of a mem-

ber’s term, they must complete a minimum of 6 hours of instruction in public records laws,

open meeting laws, local government relations, the K-12 education system, ethics, violence

and sexual violence prevention, nancial management, duciary duties, and employment and

contract laws.

ECS

NASB

New Jersey

The state requires rst-year school board members to complete a training program that

includes instructional programs, personnel, scal management, operations, and governance.

In subsequent years, board members must complete a school district governance training

on school law and other information to enable the board member to serve more eectively.

The New Jersey School Board Association is charged with providing school board member

training, and outlines the training schedules based on 4 topic areas. One of the areas focuses

on student achievement.

ECS

NJSBA

New Mexico

According to state statute 22-5-12, school board members are required to attend 5 hours of

training a year.

NMSBA

New York

Section 2102-a of the Education Law requires certain board members to obtain a minimum

of 6 hours of training on the nancial oversight, accountability, and duciary responsibilities

of school district and BOCES (i.e., Board of Cooperative Education Services) board members.

School district and BOCES board members who were appointed, elected, or re-elected for

a term that begins on or after July 1, 2005, must obtain the training. School board training

courses are required to address nancial oversight, accountability, and duciary responsibili-

ties of school board members.

NYSED

North Carolina

The state requires all local boards of education members to receive a minimum of 12 hours

of training every 2 years. The training must include public school nance in addition to public

school law and the duties and responsibilities of local boards of education.

ECS

NCSBA

15

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

State Training Requirement Source

Oklahoma

The state requires all elected school board members to undergo training. The law indicates

that training hours depend on the length of term served by the board member. Training

requirements include one hour each of nance training, open records/meetings training,

and ethics training. New members must complete 9 hours of continuing education (three for

incumbent members). Instruction is provided by the Oklahoma School Boards Association or

the Oklahoma Department of State.

ECS

OSSBA

Pennsylvania

The state enacted an omnibus education bill in 2017 requiring the department of education to

provide a training program for new school directors (board members). The training must con-

sist of a minimum of 4 hours of training that addresses instruction and academic programs,

personnel, scal management, operations, governance, ethics, and open meetings. Additional

training requirements for reelected or reappointed school directors, as well as charter school

trustees, are also included.

ECS

PADOE

South Carolina

The state requires all elected or appointed members of a school district board of trustees

to complete an orientation program covering the powers and duties of a board member

within one year of taking oce. The orientation, which must be approved by the state board

of education, must include training on “policy development, personnel, superintendent and

board relations, instructional programs, district nance, school law, ethics and community

relations.”

ECS

Tennessee

The state law outlines the specic training course requirements for new and experienced

board members and the timeline for approving new training courses annually. State Board

policy 2.100 includes the list of approved training courses for local school board members to

complete their annual training requirement.

TNBOE

Texa s

Continuing education requirements for independent school board trustees are established

in Texas Education Code, §11.159, Texas Administrative Code §61.1, and Texas Government

Code, §§ 551.005, 552.012, and 2054.5191. There is a table that provides a summary of these

requirements. For example, school board members are required to participate in training on

“Evaluating and Improving Student Outcomes” for 3 hours within the rst 120 days in their

oce and 3 hours every two years.

TEA

TASB

Virginia

The state requires its state board of education and local boards of education to participate in

professional development. The state board must participate in professional development on

“personnel, curriculum and current issues in education.” For local boards of education, mem-

bers must participate annually in professional development at the state, local, or national

levels of governance, including “personnel policies and practices; the evaluation of personnel,

curriculum, and instruction; use of data in planning and decision making; and current issues

in education as part of their service on the local board.”

ECS

16

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

State Training Requirement Source

Washington

There are three types of training required by the Washington Legislature for school directors,

but the Oce of Native Education training is required for only 39 school boards. In July 2021,

Senate Bill 5044 became law, requiring cultural competency, diversity, equity, and inclusion

training for Washington state’s K-12 public school educators, district leaders, and school

directors. Every school director must complete training on the Open Public Meetings Act

(OPMA), Public Records Act (PRA), and records retention within 90 days of taking the oath of

oce following appointment or election.

WSSDA

Simply put, data about school districts and school boards corroborate the description “ten thousand

democracies” about the diversity of the U.S. school governing system. In general, school board members are

elected ocials who make decisions and policies based on their district’s unique conditions and the expectations

of their communities.

Source: State-Information-Request_School-Board-Training-Requirements.pdf (ecs.org); Mandatory Board Member Training

| IASB; School Board Trustee Training | Texas Education Agency; A How-To Guide to Required Training by Tier for Texas

School Board Members (tasb.org); Board Member Training :Educational Management:NYSED; Required Training - WSSDA;

Governance (pa.gov); Oklahoma State School Boards Association (ossba.org); Accountability Act - New Jersey School Boards

Association (njsba.org); statute.aspx (ky.gov); New School Board Members – Florida School Boards Association (fsba.org);

Board Training – New Mexico School Boards Association (nmsba.org); OpenExhibitDocument (state.nv.us); Get on Board:

Training (alabamaschoolboards.org); Sec. 123B.09 MN Statutes; School Board Training Advisory Committee (tn.gov); Missouri

Association of Rural Education - Board Training Information (moare.com); Louisiana Laws - Louisiana State Legislature; MSBA

- Mississippi School Boards Association > Board Members > Board Service (msbaonline.org); Board Member Training - North

Carolina School Boards Association (ncsba.org)

17

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Part I I

One Common Goal: Every Student’s Success

“Improving student achievement became the mission for public education more than a decade ago, putting

educators, including school boards, on notice” (Lorentzen and McCaw, 2019). e COVID-19 pandemic added

more pressure to accomplishing this mission. Now, school leaders must tackle the weightiest policy question

― “how to make up learning lost during the most prolonged and widespread instance of school closures in

American history” (Kogan, 2022).

e Nation’s Report Card, aka NAEP, provides a common measure of student achievement across the country.

NAEP is, and for decades has been, “America’s premier gauge of whether its children — all our children — are

learning anything in school, whether they’re learning any more today than years ago, and whether the learning

gaps among groups of children are narrowing or widening” (Finn, 2022). A brief review of NAEP data should

be a good start to initiate a conversation with all stakeholders about improving academic achievement for all

students.

NAEP Basic vs. Procient

NAEP achievement levels are performance standards that describe what students should know and be able to

do. NAEP reports percentages of U.S. students performing at or above three achievement levels (NAEP Basic,

NAEP Procient, and NAEP Advanced). While the NAEP Procient level is not intended to reect grade-level

performance expectations, the information helps parents, school leaders, and educators to better understand

what fourth- and eighth-graders should know and be able to do in math, reading, and other subjects (e.g.,

history, civics, science).

To close the student achievement gap, school leaders should understand the NAEP Basic and Procient Levels as

achievement benchmarks. In general, students performing at the NAEP basic level have fundamental knowledge

and skills about the subject (Table 3). By contrast, students performing at the NAEP procient have acquired

higher-order comprehension skills and developed adequate critical thinking, analytical, and problem-solving

abilities. If educators and school leaders can strategically help most students to advance from the basic to the

procient level, the next Nation’s Report Card will show a signicant dierence.

18

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Table 3. Examples of What Students Can Do at NAEP Basic vs. Procient Levels

Source: NAEP Nations Report Card - The NAEP Reading Achievement Levels by Grade (ed.gov); NAEP - NAEP Mathematics

Achievement Levels by Grade (ed.gov)

Reaching the Basic Achievement Level: Why It Matters

Students not reaching the basic achievement level should be a source of great concern. In 2022, 39% of American

fourth-graders performed below the NAEP basic achievement level in reading. For eighth-grade math, 40% of

students performed below the basic level (Figure 3).

• More than half of Black fourth-graders (57%), more than half of Hispanic fourth-graders (51%), and more than half of American Indian/

Alaska Native (AI/AN) fourth-graders (57%) failed to reach the basic level in reading.

• Among fourth-graders who are eligible for the National School Lunch Program (NLSP), more than half (52%) could not reach the basic level

in reading.

• Nearly 3 in 4 students with disabilities (71%) and about 2 in 3 English language learners (67%) performed below the basic level in fourth-

grade reading.

• Compared with suburban students (34%), more rural students performed below the basic level in fourth-grade reading (36%). For eighth-

grade reading, more rural students (31%) performed below the basic level than their peers in suburban schools (28%).

20

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Reaching the basic achievement level is the rst step for students to become procient in reading, math, and

other subjects. Helping students reach the basic level should be an urgent goal for educators and school leaders

to solve the national education crisis. e fact that most disadvantaged students cannot reach the basic level in

reading and math is a serious equity issue. In Kansas, the district leaders of Dodge City Public Schools (DCPS)

have made a clear case for promoting districtwide literacy programs. On the district website, they educate their

constituents by listing the following facts:

Why is literacy important?

• Illiterate workers earn 30-42% less than those who are literate.

• 43% of adults living in poverty can barely read or can’t read at all.

• A Harvard University study found that people with at least 12 years of education live a year-and-a-half longer than those with less education.

• Data from the U.S. Department of Justice show that 75% of state prison inmates have low literacy skills or did not graduate from high

school.

Helping All Students to Reach Prociency in Reading and Math

“e Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Math and Reading,” e New York Times reported

(Mervosh, 2022). “e pandemic has smacked American students back to the last century in math and reading

achievement,” according to Education Week, which describes itself as America’s most trusted resource for K-12

education news and information (Sparks, 2022). It is true that student learning has been seriously disrupted by

the pandemic, but student achievement data show another concerning trend over the past 20 years.

Nationwide, only around 30% of public school students have performed at or above the NAEP procient level in

reading and math for decades (Figure 4). Even in the “best” years (i.e., students performing the best, compared

with other years), only 37% of fourth-graders and 35% of eighth-graders reached the procient level in reading.

As for math achievement, in the “best” years, only 41% of fourth-graders and 34% of eighth-graders performed

at or above the procient level.

21

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Figure 4. Public School Students Who Performed at or Above NAEP Procient Levels in Reading and Math

Source: NDE Core Web (nationsreportcard.gov)

If we use 2017 as the year when students performed the best in reading and compare student performance

between 2017 and 2022, we can see the discouraging situation that has lasted for half a decade (Table 4).

Nationwide, 65% of fourth-graders could not reach the procient level in reading in 2017, and in 2022,

the percentage was 68%. If we look at disaggregated data, most students from low-income families and

disadvantaged backgrounds could not reach the procient level in fourth-grade reading. For example,

• Nine in 10 fourth-graders who were identied as English language learners performed below the procient level in reading (91% in 2017;

90% in 2022).

• Nearly 9 in 10 fourth-graders who were identied as students with disabilities performed below the procient level in reading (88% in 2017;

89% in 2022).

• More than 8 in 10 Black students in fourth grade could not reach the procient level in reading.

• Approximately 8 in 10 Hispanic students in fourth grade performed below the procient level in reading.

• About 8 in 10 fourth-graders from low-income families (i.e., students eligible for the National School Lunch Program) performed below the

procient level in reading.

22

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Research suggests that being unable to read prociently as early as fourth grade has serious consequences.

Without foundational reading skills, students oen lose interest and motivation in middle school, struggle to

keep up academically, fail to master the knowledge and content needed to progress on time, and in the end, drop

out of school (e Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2010). Many studies have examined and explored philosophical

and pedagogical ways to help students become procient readers. For example,

• Parental Involvement — Evidence shows that time engaged in reading is associated with reading achievement, and one way to increase the

sheer amount of reading done by students is to encourage reading at home (Crosby et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2009). Researchers nd that

home involvement is a key ingredient in student reading success (Fawcett, Padak, and Rasinski, 2013).

• Educator Professional Training — A rich body of literature suggests that graphemes representing phonemes in alphabetic writing systems

do not typically come naturally to children, and most children must be taught explicitly about phonetics to make further progress in reading.

Researchers suggest that teachers should receive more professional training to teach students how to read. In an empirical study, Correnti

(2007) found that teachers who received professional development in how to teach reading oered 10% more comprehension instruction

than teachers without this training. In recent years, some states passed laws requiring “evidence-based and scientically-based” reading

instruction. In Colorado, for example, teachers are required to go through 45 hours of training to learn the science of how to teach literacy

(Eden, 2022).

• District Leadership — “Student outcomes are strongly linked to adult mindsets, and teachers and leaders at high-performing schools

tend to share a common set of high expectations for success” (CAO Central, 2021; de Boer et al., 2018). Delagardelle (2008) conducted a

two-year in-depth interview with school leaders and educators and found that “There was a signicant dierence in beliefs between school

board members in high- and low-achieving districts: those in high-achieving districts often expressed a positive belief in students’ potential

and in the district stas’ ability to improve achievement, while those in low-achieving districts did not express this belief and more often

blamed outside factors and the students themselves for low achievement” (CSBA, 2017).

Figure 4. Public School Students Who Performed at or Above NAEP Procient Levels in Reading and Math

Source: NDE Core Web (nationsreportcard.gov)

23

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

In summary, without solid foundational reading and math skills, it is hard for students to go into any pathways

to postsecondary success. Fostering an education environment in which all students can be procient in reading

and math during their K-12 education should be a mission for school leaders.

Increasing Graduation Rate and Raising the Graduation Bar

At the core of school board accountability is to see every student successfully graduate from high school

(Darling-Hammond et al., 2016; ED, 2009). For decades, school leaders and educators have made great eorts

to help students to complete K-12 education. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES,

2023), the overall dropout rate for 16- to 24-year-olds decreased from 8.3% in 2010 to 5.2% in 2021. During this

time, the dropout rate declined substantially among Hispanic (from 16.7% to 7.8%), American Indian/Alaska

Native (from 15.4% to 10.2%), and Black students (from 10.3% to 5.9%).

Despite the progress, increasing graduation rates, particularly of students from disadvantaged backgrounds, is

still a priority for all school leaders. According to NCES (2023), in the 2019–2020 school year, the graduation

rates for students with disabilities (71%), English learner students (71%), and economically disadvantaged

students (81%) were below the U.S. average graduation rate (87%)

.

• As shown in Figure 5 and based on the Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate (ACGR), in 2019–20, the U.S. average graduation rate for Black

public high school students (81%) was 9 percentage points lower than that of White students (90%) and 11 percentage points lower than

that of Asian/Pacic Islander students (93%).

• Black students had lower graduation rates than White and Asian/Pacic Islander students in every state and the District of Columbia.

Wisconsin reported the largest gap between the graduation rates for Black and White students (23 percentage points).

• Figure 6 shows that in 2019–20, the U.S. graduation rate (based on the ACGR) for Hispanic public high school students (83%) was about

8 percentage points lower than that of White students (90%) and 10 percentage points lower than that of Asian/Pacic Islander students

(93%).

24

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Figure 4. Public School Students Who Performed at or Above NAEP Procient Levels in Reading and Math

Note: The Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate (ACGR) refers to the percentage of U.S. public high school students who graduate

on time. To calculate the ACGR, state education agencies rst identify the “cohort” of rst-time 9th-graders in a particular

school year. The cohort is then adjusted by adding any students who immigrate from another country or transfer into the

cohort after 9th grade and subtracting any students who subsequently transfer out, emigrate to another country, or die. The

ACGR is the percentage of students in this adjusted cohort who graduate within 4 years of starting 9th grade with a regular high

school diploma or, for students with the most signicant cognitive disabilities, a state-dened alternate high school diploma.

Source: COE - Public High School Graduation Rates (ed.gov)

26

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Beyond increasing graduation rates, raising the graduation bar has also become an urgent call. For instance,

while rural students, on average, have higher graduation rates compared with their peers in urban schools, rural

student college enrollment has been low (NCES, 2022). In rural areas, more adults (age 25 and above) only had a

high school degree as their highest level of educational attainment (34%) in 2019, compared with their city (23%)

and suburban peers (25%). At the same time, compared with adults in cities (37%) and suburban areas (37%),

only 25% of rural adults had a college degree (i.e., a bachelor’s or higher degree).

Evidence shows that parents, particularly low-income parents, have concerns about the future of their children

aer high school. In a statewide poll of Texas parents (EdTrust, 2023), 65% worry about whether their child

is prepared for life aer high school; this is especially true for the parents of Spanish-speaking students (86%)

and students from low-income backgrounds (70%). In brief, raising the graduation bar means ensuring that all

students graduate with the knowledge and skills necessary to thrive in college and the workforce (ED, 2012).

27

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 1: Pathways to Postsecondary Success

Career, College, and Service: Three Pathways to

Postsecondary Success

Being procient in literacy and numeracy is a critical part of all pathways to postsecondary success

(Fazekas and Warren, n.d.). Many school board members believe that the objective of K-12 education

is to prepare students for college, career, and citizenship. From the perspective of school district

leadership, pathways to success often mean:

• Preparing students for college both academically and psychologically.

• Providing career-geared programs for students who may want to start a job immediately after high school.

• Taking advantage of scholarships and other opportunities provided by the military or other civil service

sectors, and then going into public service after graduation.

With the above-mentioned pathways in mind, school boards may ask questions about how their

district policies can help every student in a focused way. Schools should support all students in

setting their own achievement goals. One vision of a district may be for all students to know what they

need to learn; for educators to teach students the steps to get there and motivate every student to do

the work; and for all students to accomplish what they need to have a chance to succeed. In practice,

school leaders may start by thinking about what a student prole looks like and what a graduate

would say in terms of “When I graduate, this is what I can do for my life.”

There are many education, training, and work-based pathways to decent jobs. Researchers have

dierent ways of categorizing pathways to postsecondary success. For instance, in May 2023, the

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW) released a new report titled

“What Works: Ten Education, Training, and Work-Based Pathway Changes That Lead to Good Jobs.” In

the report, CEW researchers identied three dierent combinations of pathway changes:

• Expanding access to bachelor’s degree programs and increasing bachelor’s degree completion.

• Expanding access to middle-skills programs and also increasing completion of either an associate’s or a

bachelor’s degree.

• Moving young adults on the high school pathway from a low-paying occupation to a STEM or other high-

paying profession while ensuring continuous employment from ages 20 to 22.

Simply put, every student should have a strategic learning plan; all students should feel capable and

prepared when they graduate.

28

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Part III

School Board Accountability, Eectiveness, and Evaluation

Accountability means “the fact of being responsible for your decisions or actions and expected to explain them

when you are asked” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionary) or “the fact of being responsible for what you do and able to

give a satisfactory reason for it, or the degree to which this happens” (Cambridge Dictionary). Accountability,

especially, refers to “an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions”

(Merriam-Webster Dictionary). In brief, accountability means responsibility, frequently used in the context that

elected ocials are entrusted with public duties.

School Board Accountability and Democracy

Governing schools has become far more dicult and complicated since the pandemic, and many school boards

have become “mired in partisan political controversies that have little to do with their core function: educating

students” (Harvard Kennedy School of Government, 2023). Because of many challenging situations that school

boards are facing today, society at large, including scholars and researchers, has raised the question — “Should

school boards run schools?”

In a democratic system, perhaps it is more meaningful to ask how responsive U.S. school boards are to the

preferences of voters than to ask whether school boards should govern. eoretically, the accountability of school

boards is intricately intertwined with the fact that boards are primarily elected ocials, and voters are supposed

to know what they are looking for and what they expect regarding the eectiveness of boards. However, research

in this eld is limited, and no conclusive answer has been provided.

• Earlier studies found that the 2000 elections revealed considerable evidence that voters evaluate school board members on the basis of

student learning trends, but during the 2002 and 2004 school board elections, “when media (and by extension public) attention to testing

and accountability systems drifted, measures of achievement did not inuence incumbents’ electoral fortunes” (Berry and Howell, 2007).

• Ren (2022) examined how responsive school boards were to the preferences of their voters in Virginia. One hypothesis the researcher tested

in the study is that “If a school district has at least one incumbent board member up for reelection in 2020, it will be less likely to adopt a

remote learning policy during the Fall 2020 school semester.” While the ndings are complicated and narrowed to certain specic issues, the

study provides preliminary evidence that “the increased attention American voters are investing in local school boards is not in vain.”

Another issue surrounding board accountability and democracy is representation. A few recent, empirical

studies provide dierent perspectives on whether elected ocials of school boards represent their district’s

parents and community and how representation may inuence student learning and achievement. Some studies

focus on interest groups, while others emphasize the connection between racial/ethnic minority representation

and student achievement. e following are some examples:

29

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

• Hartney (2022) found that union-endorsed school board candidates have done exceptionally well — won roughly 70% of all competitive

races — in elections held across all three states (i.e., California, Florida, and New York). The criticism is that school board elections

nowadays have become increasingly political, more focused on interest groups than on students, and such elections can lead to ineective

governance of school boards and hence aect student learning. An example the researcher provided is that during the pandemic, “students

who attended school in districts where their teachers’ unions are very active in electioneering were the least likely to receive signicant in-

person instruction during the 2020-21 school year.”

• Shi and Singleton (2021) analyzed data of California school board elections between 1996-2015 and found that there is no statistically

signicant relationship between an educator being elected to serve on the school board and student achievement. While the study has

limitations, the researchers suggest that electing an educator to the school board has an insignicant eect on increasing student scores in

reading and math or increasing high school graduation rates.

• Research in political science suggests that school districts with large Hispanic, Black, or other racial/ethnic minority student populations

benet school board elections, as more minority board members can be elected to represent the community, empower and engage the

parents they represent, and increase the performance of disadvantaged students (Morel, 2021; Morel and Nuamah, 2019; Morel et al.,

2016). Kogan et al. (2020) found that greater representation of racial and ethnic minorities on school boards has a positive eect on the

achievement of non-White students; specically, “increases in minority representation could lead to cumulative achievement gains of

approximately 0.1 standard deviations among minority students by the sixth post-election year.”

What Research Says About School Board Accountability and Student Achievement

Research suggests that with more federal and state laws being passed to regulate K-12 education, school board

members seem to have less authority to make decisions, yet are increasingly held accountable for student

performance (Alsbury, 2008). eoretically, with a clear division of roles and responsibilities, school boards

can provide accountability and monitor performance, thus creating the conditions for improving student

achievement (Hess, 2008). While there is a shortage of empirical studies on school board accountability and

student achievement, evidence shows that district leaderships do have an impact on student achievement

(Leithwood et al., 2019; Plough, 2014).

• Researchers (Waters and Marzano, 2006) conducted a meta-analysis of 27 studies and found a positive relationship between district-

level leadership and student achievement. In districts with higher levels of student achievement, local school boards always ensure that

student achievement goals are the primary focus of the district’s eorts and that no other initiatives detract attention or resources from

accomplishing these goals.

• In 2022, Sutherland published a research study titled “Tell them local control is important”: A case study of democratic, community-

centered school boards. The researcher focused on small rural school districts in Vermont and conducted a qualitative multiple case study

of local school boards. The ndings of this study explained how small, locally controlled school boards can employ elements of democratic

governance and how community-based school board governance can inuence students’ schooling and enhance student learning.

• In a dissertation study (Holmen, 2016), the researcher investigated 23 school districts and interviewed and surveyed school board members

in Washington State. “The ndings of this research study conrm and extend the empirical evidence that has been presented over the last

20 years linking school board characteristics and improved student achievement results” (Holmen, 2016).

States’ Requirements for School Accountability

State governments use accountability systems to “measure student and school performance, identify schools in

need of support, and prompt action to raise student achievement” (e Education Trust, 2023). Dierent states

may focus on dierent measures or standards in their accountability systems. In general, school accountability

systems attempt to help parents, communities, and policymakers measure school quality to make decisions and

target resources to support student achievement.

30

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

For example:

• Colorado’s education accountability system “is based on the belief that every student should receive an excellent education and graduate

ready to succeed.”

• Maryland’s accountability system measures school and school district performance and provides the information to educators, parents, and

the public for improving student achievement.

• In Massachusetts, the state’s accountability system aims to provide clear, actionable information to families, community members, and the

public about district and school performance.

• Michigan’s school accountability systems use statewide student assessment scores and other quality metrics to provide transparency on

school performance for all Michigan public schools.

• In New Mexico, the state government denes accountability in education as “the responsibility of students learning to teachers, school

administrators, and students and incorporates a number of factors such as test results and graduation rates, as measurements.”

• Virginia’s accountability system supports teaching and learning by setting rigorous academic standards and thorough annual statewide

assessments of student achievement.

• Texas emphasizes its annual academic accountability ratings to its public school districts, which examine student achievement, school

progress, and whether districts and campuses are closing achievement gaps among various student groups. The ratings are based on

performance on state standardized tests; graduation rates; and college, career, and military readiness outcomes.

How Districts Describe School Board Accountability

“Student achievement is the primary agenda for school boards” (WSSDA, n.d.). e Washington State School

Directors’ Association (WSSDA) has issued guiding principles about the role of school boards in improving

student achievement. As policymakers, school boards play a signicant part in “ensuring that students learn what

they need to know to be prepared as productive citizens and that they are able to demonstrate that knowledge on

state and local measures of achievement” (WSSDA, n.d.).

e Ohio School Boards Association (OSBA), as another example, believes that it is the work of school boards

to ensure a systemwide culture in which excellent teaching and successful learning can take place. According

to OSBA, school boards should commit to a continuous improvement plan regarding student achievement

throughout the district. “Accountability is based on the expectation that all students can and will excel, meaning

we expect minority students, students who live in poverty, students with disabilities and other student groups to

learn and perform the same as their peers” (OSBA, 2023).

31

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Most school districts incorporate their accountability in their vision and/or mission statements. Many

school districts explicitly state that the most important responsibility of school boards is improving student

achievement. e following are some examples:

• Montgomery County Public Schools, Maryland, implements an Equity Accountability Model. The model “moves beyond the typical state

and federal aggregate reporting to performance reporting for specic focus groups of students who have not experienced the same level of

access, opportunity or success as other students.”

• Claremore Public Schools, Oklahoma — The district’s mission is “to increase student learning and achievement.” The district’s vision is that

“ALL students will have the options to provide evidence of their learning in numerous ways while gaining necessary knowledge, skills, and

attitudes to achieve their dreams and become successful members of the community in which they live.”

• Hamilton Unied School District, California ― One of the ways in which school boards serve the community is by prioritizing student

achievement and ensuring accountability for student and district performance.

• According to the Darlington Community School District, Wisconsin, “Accountability means measuring and judging how well the district is

putting the vision into practice and making progress on key goals; Accountability starts with (1) the adoption of goals and academic and

other standards, and (2) the assignment of responsibility and authority.”

In summary, as NSBA (2018) points out in “e Key Work of School Boards Guidebook,” accountability is one

of the ve action areas (i.e., vision, accountability, policy, community leadership, and relationships) in the key

work framework of school boards, and “High academic standards, transparency, and accountability undergird a

world‐class education.”

32

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Policy/Practice Discussion Box 2: Has School Board Governance Been “Hijacked?”

Is There a Push for a “Uniform” Accountability System?

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), each state educational agency (SEA) and local

educational agency (LEA) that receives Title I Part A funds must prepare and disseminate an annual

report card that includes a variety of data about public schools. The data cover a wide range of

measures on student and school performance, accountability, per-pupil expenditures, and educator

qualications, as well as any other information that the SEA or LEA deems relevant (Cai, 2019). In a

sense, federal and state-mandated or promoted measures on student report cards look like a push

for a “uniform” accountability system.

To what extent do federal and state accountability systems impact school boards?

An earlier study reported that more than three-fourths (78%) of school boards agree — with 34%

agreeing strongly — that federal and state accountability systems have created much pressure

to the eect that boards need to “celebrate hard work and initiative” on the part of teachers

and administrators (Hess, 2010). Some researchers suggested that performance information

disseminated via school “report cards” directly shapes voter perceptions about the quality of local

schools (e.g., Chingos et al., 2012, Jacobsen et al., 2013).

It should be noted that research results regarding the inuence of federal and state accountability

systems on school board election and operation are inconclusive. For example,

• According to an early study (Jacobsen et al., 2013), under the law No Child Left Behind (NCLB), federal and state

governments attempted to implement two accountability strategies simultaneously — raising standards and public

pressure through publicizing performance data. Using data from New York City, the researchers found that parent

satisfaction declined when school performance grades dropped after the implementation of higher standards. The

authors were concerned that the public or voters might misunderstand the drop in achievement that occurs when the bar

is raised and become dissatised with school performance. They pointed out that “Because public support for sustained

and successful reforms is key, understanding how accountability policies may erode support is critical.”

• According to researchers from Ohio State University (Kogan et al., 2015), school districts in Ohio often need to put

school tax referenda on the ballot more frequently than in other states. The researchers estimated the impact of federal

performance measures on local school tax referenda in Ohio from 2003 to 2012 and found that a signal of poor district

performance increases the probability of failure of school tax levies. They concluded that a widely publicized federal

indicator of local school district performance may not necessarily lead voters to draw valid inferences about the quality

of local educational institutions. The end result may be that school districts may lose voter support for school tax levies,

which are often substantial nancial sources for schools of impoverished communities. They “call this burgeoning

phenomenon ‘performance federalism’ and argue that it can distort democratic accountability in lower-level elections.”

• In another Ohio study, researchers (Kogan et al., 2015) focused on local school board elections held from 2003 to 2012

across a sample of 611 Ohio school districts. They examined whether the federal and state accountability systems might

inuence local school board elections and lead to improvements in educational quality. Their data analysis revealed little

evidence that publicized measures of school and district performance had an impact on the likelihood of turnover on

school boards, the electoral success of sitting school board members, or turnover among district administrators.

33

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

Who Approves K-12 Curricula in Public Schools?

The State Department of Education of Rhode Island denes curriculum as “a standards-based

sequence of planned experiences where students practice and achieve prociency in content and

applied learning skills.” Curriculum is the central guide for all educators as to what is essential for

teaching and learning, so that every student has access to rigorous academic experiences. According

to the Ballotpedia research (2022):

• In 34 states, state laws task local districts with approving K-12 curricula.

• In 12 states, school boards, sometimes in conjunction with state entities, approve K-12 curricula.

• In Rhode Island, Texas, North Carolina, and Alaska, state entities, like the state board of education or the commissioner of

education, approve K-12 curricula.

School boards govern by the adoption of policies that have the force of law; the adoption of

some specic policies by boards is often required by legislative mandates and state or federal

administrative rules and regulations (California School Boards Association, Illinois Association of

School Boards, Maine School Boards Association, Pennsylvania School Boards Association, and

Washington State School Directors’ Association, 1998). In recent years, the expansion of federal

intrusion on public education has impacted local policymaking in many ways (NSBA, n.d.). However,

establishing a curriculum is primarily a state and local responsibility.

34

Ten Thousand Democracies, One Common Goal

School Board Eective Governance: A Key to High Achievement for All Students

“e lack of a unied consensus on what school boards actually do presents both a practical and theoretical

problem when attempting to research the institution” (Ford, 2013). School boards may be judged eective by

measures other than student achievement, such as their ability to balance budgets, comply with legislation, and

respond to local concerns. However, research suggests that student achievement should be the predominant

measure of interest (Land, 2002).

Empirical Research on Characteristics of Eective School Boards and Student Achievement

Eective means “successful or achieving the results that you want” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023). High

achievement for all students is one of the most important successful results that school boards want through

their eective governance. According to Lorentzen (2013), “Whatever their decisions, boards must be able to

justify their actions to the community as eectual in promoting the smooth functioning of the district in all ways

conducive to optimal student achievement.”

e following empirical studies reported data on the relationship between some characteristics of eective school

boards and student achievement:

• Lorentzen (2013) conducted a non-experimental quantitative study that examined the relationship between school board governance

behavior (i.e., boardsmanship) and student achievement scores. The researcher found that student achievement signicantly correlated

with school boards that could (a) provide responsible school district governance, (b) set and communicate high expectations for student

learning with clear goals and plans for meeting those expectations, (c) create the conditions districtwide for student and sta success,

(d) hold the school district accountable for meeting student learning expectations, and (e) engage the community.

• Ford (2013) surveyed school board members from six states, where school board members often make signicant time and eort

commitments to serve in a position that does not provide them with economic support. The researcher found that (a) school boards