City University of New York (CUNY) City University of New York (CUNY)

CUNY Academic Works CUNY Academic Works

Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center

9-2017

The Behavioral Effects Divorce Can Have on Children The Behavioral Effects Divorce Can Have on Children

Wanda M. Williams-Owens

The Graduate Center, City University of New York

How does access to this work bene;t you? Let us know!

More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2314

Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu

This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY).

Contact: AcademicWorks@cuny.edu

Running head: CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

THE BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS DIVORCE CAN HAVE ON CHILDREN

By

Wanda Williams-Owens

A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts,

The City University of New York

2017

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

II

© 2017

Wanda Williams-Owens

All Rights Reserved

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

III

THE BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS DIVORCE CAN HAVE ON CHILDREN

by

Wanda Williams-Owens

This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies

in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts.

__________________________ ______________________________

Date Julia Wrigley

Thesis Advisor

__________________________ ______________________________

Date Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis

Executive Officer

THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

IV

ABSTRACT

The Behavioral Effects Divorce Can Have On Children

by

Wanda Williams-Owens

Advisor: Professor Julia Wrigley

According to a statistical study (Cherlin et al. 1991) 40% of children who live in the

United States will experience parental divorce before they reach the age of 18. Consequently,

many children are affected by the process of divorce and its finalization. When my daughter was

just nine years old, she asked incredulously why my husband and I were the only married couple

in our neighborhood? After twenty-two years of marriage, I realized long-term marriages in my

community are not conventional. When parents’ divorce, children often face the loss of one

parent's constant presence and economic stability; as a result, stress may take a tremendous toll

on the children. Although independently these consequences are consequential, they do not

address the child's academic and social life, or their perspective on what a healthy relationship

may resemble. Further, a child’s age may play a significant role in divorce. Research suggests

that while older children tend to suffer when parents’ divorce, younger children, in most cases,

suffer more. In this thesis, I will examine the short and long-term adjustments of children who go

through their parents’ divorce and the specific behavioral problems that may come with the

dissolution of their parents’ marriage.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

V

Acknowledgements

This thesis is dedicated to my dad, the late Alton Williams, and to my mom, Margaret

Howard, for giving me life, and for showing me that although divorce has a significant impact on

the family, that their love for their only child always remained the same. To my husband,

Thomas Owens, thank you for proving to me that you need us just as much as we need you. To

my baby girl, Tia Monaih Owens, thank you for being our constant reminder of why we love

being a family.

I would like to also express my deepest gratitude to my Professor/Advisor Mrs. Julia

Wrigley for her unwavering support and guidance.

Lastly, with great appreciation and humility I thank GOD for his constant presence in my

and my family’s lives.

LOVE

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

VI

Table of Contents

Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………..IV

Family ……………………………………………………………..………………………………1

Divorce……………………………………………………………………...…………………..…2

Figure 1.. Divorce Rates from 1970-2010……………………………………………….…3

Effects Divorce Has On Children With Disability………………………..…………..……..……5

Figure 2. Marital History for parents of a child with DD V.S. a child with no disabilities….7

Preschoolers And Adolescents Whose Parents Divorce………………………………..…………8

Father-Daughter Relationships After Divorce…………………………………..…...………..…11

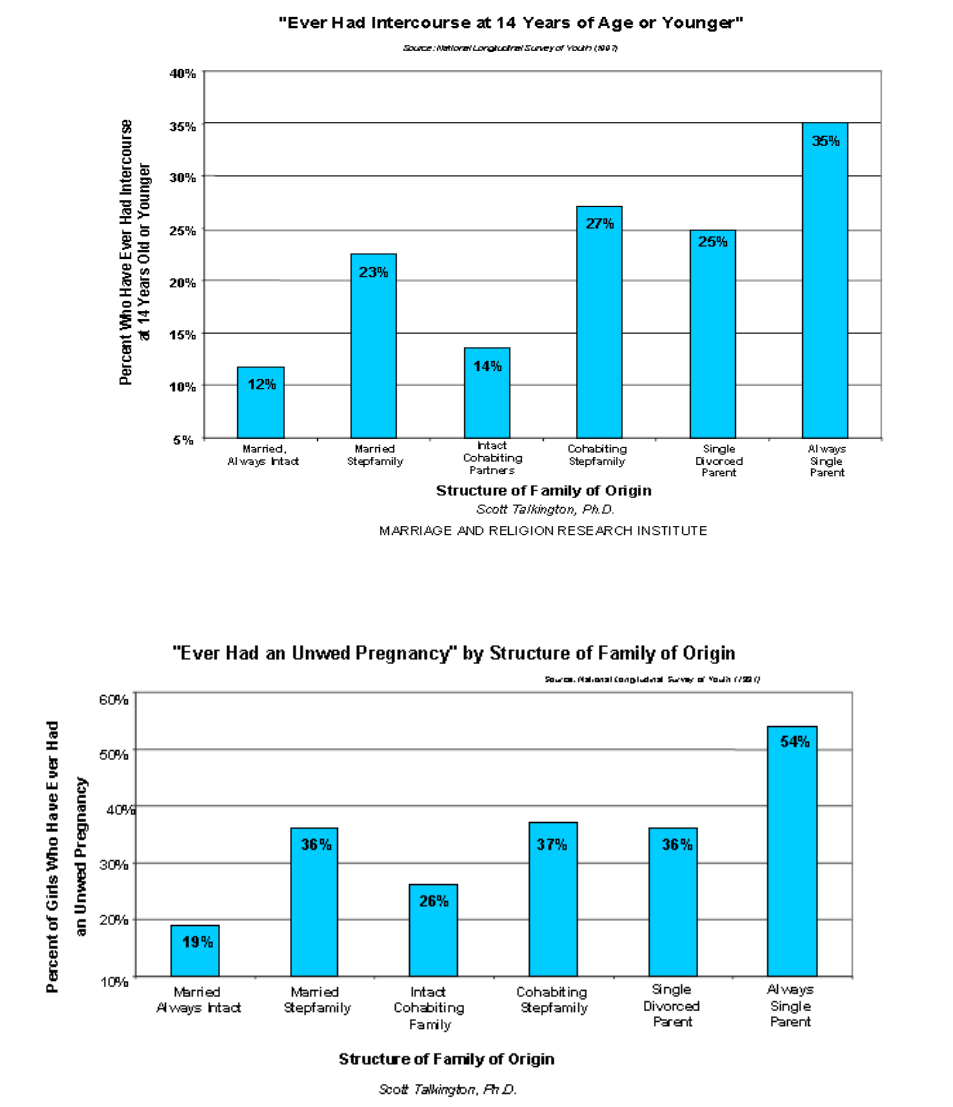

Figure 3. Intercourse at 14 years old or younger…………………………………………….13

Figure 4.Unwed pregnancy's…………………………………………………………………13

Father And Son Relationships After Divorce ……………………………..……………………..14

Increased Crime Rates………………………..………………………………………………….15

Figure 5 . Juvenile Incarceration rates in Wisconsin for children of divorce…………………16

Depression And Young Adults……………………………...………………………...…………17

Figure 6 . Variables Included…………………………………………………………………18

Figure 7. First Year Students GPA……………………………………………………………19

Adult Children Affected By Divorce…………………………………………………...………..20

Blending Of Families…………………………………………………………………………….21

Figure 8. Sexual Abuse by Family Structure…………………………………………………..25

Fathers as the Custodial Parent……………………………………………..……………………26

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

VII

Depressed Mothers and the Effects On The Children………………...…………………………29

Adopted Children and Divorce……………………………..……………………………………32

Figure 9. Constructs Reported by Mother…………………………………………………….35

Figure 10. Constructs Reported by Father……………………………………………………36

Figure 11. Constructs reported by Child………………………………………………………37

Children Who Live In Sweden…………………………………………………………………..37

Figure 12. Control and Outcome Variables……………………………………………………38

Figure 13.Risk Behaviors and conduct problem………………………………………………39

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….………………41

References……………………………………………………………………………..…………45

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

VIII

List of Figures

Figure 1.. Divorce Rates from 1970-2010 ..................................................................................... 3

Figure 2. Marital History for parents of a child with DD V.S. a child with no disabilities ........... 7

Figure 3. Intercourse at 14 years old or younger .......................................................................... 13

Figure 4.Unwed pregnancy's ........................................................................................................ 13

Figure 5 . Juvenile Incarceration rates in Wisconsin for children of divorce ............................... 16

Figure 6 . Variables Included ....................................................................................................... 18

Figure 7. First Year Students GPA ............................................................................................... 19

Figure 8. Sexual Abuse by Family Structure................................................................................ 25

Figure 9. Constructs Reported by Mother .................................................................................... 35

Figure 10. Constructs Reported by Father ................................................................................... 36

Figure 11. Constructs reported by Child ...................................................................................... 37

Figure 12. Control and Outcome Variables .................................................................................. 38

Figure 13.Risk Behaviors and conduct problem .......................................................................... 39

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

1

Family

An anonymous quote states: "F.A.M.I.L.Y is one of the strongest words anyone can say

because it is believed to stands for: "Father and Mother I Love You!!”. Whether dwelling

together or separated, the family constitutes a fundamental social unit, consisting of the parent(s)

and their offspring. Parents play a vital role in the emotional growth of children. They help them

define who they are as human beings and influence how each adapts to societal norms. The home

is the first place children discover the importance of values and what it means to belong. From

childhood youth are conditioned to believe that family comprised of a mother, father, and

children; but family is defined as “a group of people who are united by ties of partnership and

parenthood consisting of a pair of adults and their socially recognized children that is otherwise

known as the known as nucleic or elementary family, or a group of persons united by the ties of

marriage, blood, or adoption, constituting a single household and interacting with each other in

their respective social positions” (Encyclopedia Britannica online, 2017). While this definition

focuses on what might be considered traditional families, the ties of “partnership” can include,

and increasingly do, unmarried couples who choose to live together in a family formation and

families can also include single parents living with children. Whatever the form of the family,

the primary role of parents has always been to guide their kids and to ensure that their needs are

satisfied. From birth, infants rely on parents for protection, emotionally and physically. By the

simplest touch or the sound of a voice, babies can determine whose voice they hear. "Before

birth, the brain is being set up to learn a language,” says Barbara Kisilevsky a nursing professor

at Queens University in Ontario" (abcnews.go.com). Thus, before a baby is born, it begins to

develop emotional ties to its surroundings. As children grow, they look to their role models to

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

2

determine what acceptable behavior look likes. Because divorce is prevalent, as are the births of

children to single mothers, social understandings of families have broadened.

DIVORCE

The first occurrence of divorce in the American colonies is said to have occurred around

1643, at a Puritan court in Massachusetts. Since then, there has been an increase in the number of

kids who now live in single-parent households. In the 1960’s, Census data showed that 9 percent

of children were a product of single-parent families. In some of these cases, the parents were

never married while in other cases the parents divorced. Over the last several decades, this

percentage has increased by 28 percent (McLanahan and Percheski 2008). In fact, Sheela

Kennedy and Stephen Ruggles from the University of Minnesota found that the divorce rate

hasn't declined since 1980, “And when they controlled for changes in the age composition of the

married population (the U.S. population was younger in 1980, and younger couples have a

higher risk for divorce), they found that the age-standardized divorce rate has actually risen by an

astonishing 40 percent since then” (The Washington Post 2017).

The African American community suffers from the highest percentage of divorce.

According to Cherlin (1992) and to Farley and Allen (1987) in the 1970’s over 68 percent of

African American couples were married and lived together; this number has dramatically

decreased over the years. “According to the 2000 U.S. Bureau of Census, “16% of African

American males were married, compared to 60% of White males. On the other hand, 37% of

Black females were married in comparison to 57% of White females” (Harris & Bradley p.2.

2004).

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

3

Figure 1. Divorce Rates from 1970-2010

As divorce rates continue to increase, the laws that govern divorce have changed over

time. Judicial courts deemed it necessary to oversee the amount of child support and alimony

awarded to a parent and exerts particular control over what is known as fault-based divorces.

Although fault-based divorce laws still exist in many states, the Family Support Act of 1988

introduced the no-fault divorce law, which enables individuals to divorce without proving just

cause for the divorce. This bill was also passed as a result of the increase in single-mother

households and the low amounts of child support mothers or fathers often received (Peters 1986).

The very fact that divorce rates have strikingly increased and that new laws governing divorce

have been established show that divorce could easily be regarded as part of the martial process.

In the past, divorce was viewed as an immoral event; it was considered a social disgrace,

especially if children were involved. Today, many people divorce for a multitude of reasons.

Marriage is perceived by many as a contract rather than a commitment made before God.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

4

Perhaps the entry of many women into the labor force has created a non-traditional view of

marriage. Or it could be that traditional marital standards are too much to bear in modern times.

How much does divorce impact the lives of children involved? In what ways are children

affected? What is known about what features of divorce cause adverse consequences for

children? How will the effects show outwardly? This paper seeks to examine the effects of

divorce on children’s well-being and will assess the extent to which divorce contributes to

children’s behavior problems.

Sociologist and functionalist Talcott Parson argued that a stable social system influences

an individual’s value within society. He believes families should be aware of the gender roles

that are assigned to them upon formation. While men take on the "instrumental role,” providing

financial support, women take on the "expressive role,” ensuring that the emotional needs of the

children and the husband are met. Parson emphasizes that in order for a marriage to be successful,

the family structure must be stable (Parson and Bales 1955, p.315). Throughout the years,

research indicates that there has been a decrease in marital stability and attributes this lack to

several different factors. Stevenson and Wolfers (2007) view technological changes and

women’s economic gains as having spurred the rise of divorce. More women are spending less

time on household chores due to the myriad of household appliances that have been invented,

which decreases the amount of time spent on manual labor. Washers, dryers, and dishwashers are

examples of products that have increased productivity in homes and have allowed women to

become a significant part of the workforce. Ultimately, the time demands that are associated with

women’s entry into the workforce can, in fact, strain a marriage, have an adverse impact on how

children perceive divorce and can have profound effects on their psychological and emotional

well-being. Children, regardless of age, require some level of loyalty, trust, security, safety, and

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

5

a sense of belonging. During and after the divorce process, each child experiences different

levels of psychological trauma. Studies have shown that children who experience divorce often

have an increase in antisocial behavior, anxiety, and depression, along with increased delinquent

and aggressive behavior. Self-blame and abandonment fears are also known contributing factors.

Depending on how parents handle the divorce process these feelings can easily diminish within a

child. Statistics show that in the United States, more than a million children have experienced

some level of social and cognitive harm from a parental divorce that has left them vulnerable

(Fagan and Churchill 2012). On the other hand, Weiss (1979, p. 47)) suggests that divorce allows

children to "grow up a little faster." The change in family structure may require a different set of

rules and responsibilities which may come in handy later in life. In addition, children of divorce

often assume more responsibility at an earlier age than their peers. I can attest that this is

attributed to that the fact that single parents who work are unable to afford a babysitter; as a

result, children are forced to stay at home alone or have to do more chores at home. Weiss also

argues that the consequences of divorce—additional responsibility and following a different set

of rules—could help make children more competent in social and practical matters during

adulthood. Throughout his study, he does not take into account those families who have children

with disabilities that need assistance or help in understanding the divorce process.

EFFECTS DIVORCE HAS ON CHILDREN WITH DISABILITY

The Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School defines a disability as “a physical

or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of an individual's major life activities.”

(42 U.S. Code § 12102 ). Children with disabilities often need assistance throughout their lives

(McCallion and Nickle, 2008; Shattuck et al., 2007; Smith, Maenner, and Seltzer 2012; Taylor

and Mailick, 2014), as functional and behavioral patterns often change. Although there are

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

6

limited studies on the effects of divorce on those families who have children with disabilities, in

households where a child has been diagnosed with a disability, parents are usually the primary

caretakers. Other family members who reside in the home with a disabled child often assist in the

caregiving process as well (Seltzer, Greenberg, Orsmond, Lounds and Stoneman 2005). A family

friend of mine lives in the same home with her autistic nephew. Since her sister passing, she is

now the primary caregiver and her son has also become significantly involved with raising his

cousin and has decided that in the event something happens to his mother, he will continue to

take care of his cousin. Having such support systems allow children with special needs to have a

sense of security and balance (Hodapp, Urbano and Burke 2010). I also have an aunt who has

autism due to a house fire. She had always lived with my grandparents when they were alive, but

since their passing, my aunts have been her primary caretakers. Family members play a vital role

in the aiding process, and must be willing and able to adapt and accommodate the needs of the

child while utilizing support groups, and finding resources that specialize in developing

interpersonal and active coping skills that could assist a family who has loved ones with

disabilities (Pruchno and Meeks 2004; Smith, Seltzer, Tager-Flusberg, Greenberg and Carter

2008; Woodman 2014). These anecdotes help people to understand why family plays such a

huge part in the life of someone who is disabled (Orsmond and Seltzer 2007; Taylor, Greenberg,

Seltzer, & Floyd, 2008) and how the separation of a family member can directly affect the child.

Reichman, Corman, and Noonan (2004) conducted a longitudinal study of mothers and

fathers who lived together 12-18 months after given birth to a baby with special needs. After

completion of the study, they found that having a child with disabilities reduces the likelihood of

the parents remaining in the same household together by 10 percent. However, parents desire to

stay in the relationship increased by 6 percent. (See chart below) Although in the table below the

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

7

participants differed in marital ages, the number of children born and lost during the marriage

and birth order, there was only a 2 percent difference in the divorce rates of those with or without

children with disabilities.

American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities _aaidd.2015, vol. 120, no. 6, 514–526

In a similar study, the researchers (Hatton, Emerson, Graham, Blacher, and Llewellyn

2010) found that preschool children with a disability often reside in one parent households

compared to couples whose children did not have special needs. These results applied to children

between the ages of nine months to three to five years old.

A larger study conducted by Urbano and Hodapp (2007) discovered that families who

had children with Down syndrome had a 7.6 percent divorce rate; parents who had children with

Figure 2. Marital History for parents of a child with DD V.S. a child with no disabilities

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

8

other special needs experienced a divorce rate of 10.8 percent, and families that had children

without any signs of disability had an 11.2 percent divorce rate.

Sabbeth and Leventhal (1984) conducted a comprehensive review on how the illness or

disability of a child affects marriages. Out of the twenty-three studies they examined, only seven

studies included measures of marital discord; four of the studies reported signs of stress within

the marriage and while the other three studies found no significant difference.

Kazak and Clark (1986) completed a study that examined children who had spina bifida,

and severe or mild impairments, and how it affected the marital status of parents. The families

whose child (ren) had a disability exhibited higher levels of marital distress. Theoretically, the

greater the impairment increases the level of marital discord. Kazak (1987) conducted another

study analyzing the parents of 125 children with and without disabilities.

The findings suggested that although mothers of the children with disabilities admitted to being

extremely stressed, the martial satisfaction of both groups was equivalent. This study concludes

that divorce rates do not increase because of the disability of the child, but are based on a host of

circumstances. Ideologically, families with disabled children divorce for the same reasons as

other families, including the inability to work together, lack of economic stability, and parental

stress.

PRESCHOOLERS AND ADOLESCENTS WHOSE PARENTS DIVORCE

Researchers have found that preschoolers are the children most vulnerable to divorce, due

to their lack of cognitive ability to fully understand the divorce process (Wallerstein and Kelly

1979). Although there is limited study, research has shown that the short-term effects often

include a high level of regression, acute separation anxiety, and abandonment issues. Children at

such a young age often feel as though they are the blame for the parental dissolution. Yet it is

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

9

hard to predict what long term effects divorce has on preschoolers due to their age. As they get

older, their level of perception increases along with their sense of awareness. Adolescents or

school-aged children are often fully conscious of the turmoil that exists within the family, and

because of this, some research indicates that they do not experience external behavioral problems

due to their cognitive development and their ability to express emotions (Hetherington 1981).

Other findings indicate that adolescents show significant signs of anger, depression, anxiety,

guilt and the inability to trust which is heightened by the level of conflict that they are exposed to

prior to and after divorce (Wallerstein and J.S 1991). Not only do these kids experience

behavioral and academic problems, but they also report a higher level of child abuse, or have

witnessed and remember their parents’ physical altercations (Dong et al. 2004; Oliver, Kuhns,

and Pomeranz 2006).

A preliminary report was created from a longitudinal study conducted in 1971, to

examine the memory, perception and the psychological development that children of divorce

experience between the ages of two and a half and eighteen years of age. 131 children from 60

families in Northern California took part in this study, and a follow-up study was conducted

throughout a ten years span. Eighteen months after the divorce, the report uncovered those short-

term effects that some psychologists agree that preschoolers often succumbed to actually had a

profound effect on the boys rather than girls. Boys often have an increased level of trouble in

school, at home and in their ability to play with others (Wallerstein, J. S., & Lewis, J. M. (2004).

At the five year mark after divorce, observation showed that children’s ability to adjust to

the change in the family dynamics is solely based on the comfort level that the parents display

during post-divorce and while living together. If the transition is not chaotic, then children tend

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

10

to adapt. Unfortunately, the report showed that one-third of the youngsters in the sample study

experienced some level of depression.

One of the earlier papers derived from this study discussed clinical interviews that were

conducted on 30 of the 33 preschoolers who were initially involved in the study who were now

between twelve and eighteen years of age, along with their parents. Out of this age group, ninety

percent of the children remained in the home with their mothers, while fifty-three percent lived

in homes where the parent was remarried, and many of these remarriages occurred within three

years of the divorce. The majority of the children remained in school and stayed in a middle class

environment although half of the fathers lived across the country. Six of the youngsters had some

involvement with the law that included petty thefts or drug sales. Overall, there did not seem to

be considerable signs of hardship. Those children who were now older (between nineteen and

twenty-eight years of age) expressed how they still remembered how they felt while their parents

were going through a divorce and many often reminisce about their lives prior to the divorce,

while younger children had no recollection of the traumatic experiences. This report determined

that although preschoolers have less cognitive ability to understand the divorce process,

preschool children are less consciously troubled. The study found that the emotional distress of

preschool children is short-term, while the older children continue to struggle with the inability

to erase the unpleasant memories (Wallerstein 1984).

Another study on the short-term and long-term effects of divorce and its impact on young

people was conducted by Forehand et al. (1997). It was an assessment of children and young

adults designed to measure whether victims of divorce suffer from a decrease in academic

readiness, grade point average, and standard intelligence test scores. Two assessments were

administered—one utilized the family court system, and the other utilized newspapers and flyers,

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

11

distributed throughout the community to recruit individuals to participate in the study. 251

participants were contacted via telephone and mail and paid $50 for their involvement. Six years

later, following the assessments, each divorced parent completed a questionnaire. A variety of

sources were used as a means of promoting validity and consistency in the findings. Reports

from teachers, children involved, and school records were analyzed. The letter grades that

students received in math, science, social studies, and English were converted into numeric

grades. During the assessment the effects divorce had on young adult’s levels of anxiety,

antisocial behavior, aggression, and their educational achievement were also factored in. The

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) approach was employed, and the results showed that young

adults and adolescents showed a significant decrease in academic preparedness. Research

suggests that the process of divorce can be extremely overwhelming for all parties. Children may

feel neglected and may feel as though their parents no longer care about their well-being, or

parental conflict can lead to academic decline. Being less academically prepared can perhaps

have an adverse effect on a young person’s desire or ability to develop the necessary scholarly

skills that are needed to further their education. The fact that children of divorce experience

different strands of emotions makes it imperative that parents work closely together in ensuring

the stability of the children.

FATHER-DAUGHTER RELATIONSHIPS AFTER DIVORCE

Father-daughter relationships are likely to suffer more emotionally prior to the divorce

than father–son relationships (Cooney 1994; Frank 2007; Hetherington and Elmore 2004;

Nielson 2011). Some fathers find it difficult to maintain a relationship with their children, which

results in fewer visitations (Cooney and Uhlenberg 1990; Umberson 1987). Fathers may

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

12

ultimately feel they have less in common with their daughters due to gender differences, and

because girls are generally closer to their mothers, their relationship with their fathers is often

underdeveloped. The fact that most men don't seek a support system and internalize their

problems means they often experience increased levels of mental stress and health (Reissman

1990), which can make it difficult to be actively involved with their children. Studies show that

men often experience higher levels of emotional distress and some experience suicidal thoughts

(Reissman & Gerstel 1985; Rosengren et al. 1989; Wallerstein and Kelly 1980), while daughters

often suffer from emotional and psychological problems (Amato & Dorius 2010; Carlson 2006;

King and Soboboleski 2006; K. Stamps, Booth and King 2009; Stewart 2003). Often earning bad

grades, in some cases, they drop out of high school. (Chadwick 2002; Krohn and Bogan 2001;

Menning 2006). This study also provided insight into the girls who do not have regular contact

with their fathers and who are more likely to participate in rebellious acts and to be arrested for

breaking the law (Coley and Medeiros 2007; C. Harper & McLanahan 2004); they have greater

self-esteem issues (Dunlop, Burns and Berminghan 2001) and partake in substantial drug and

alcohol use (Hoffmann 2002; Lerner 2004), engage in sexual activity at an early age and are

more likely to become pregnant as teenagers (Ellis et al., 2003; Nielson 2011).

It is a crucial part of a young girl’s development to womanhood that she develops a stable

relationship with her father. Girls are emotional beings who crave intimacy and closeness, and if

their relationship with their father seems out of place, it could have profound effects on them

psychologically and in their relationships with other people. Low levels of fatherly interactions

with daughters can result in insecurity issues, along with promiscuity at an early age (Ellis et al.,

2003; Nielson 2011). Such behavior interrupts the development of the child, and they can

experience externalized and internalized turmoil for the rest of their life.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

13

The charts below show the percentage of teenage girls who experience sex and pregnancy

at a young age as a result of divorce and feelings of inadequacy.

Figure 3. Intercourse at 14 years old or younger

Figure 4.Unwed pregnancy's

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

14

Moreover, if fathers have been active in girls’ lives, they often look to their fathers for

approval because they were the first males to love them and their opinions and thoughts are

valued. Children may look to their role models to determine what acceptable behavior actually

looks like. Certainly, one can see how divorce can directly affect the father-daughter relationship

due to the change in circumstances. On the other hand, why do some fathers feel the need to

distance themselves when the love for the children remains the same? In an episode of Oprah’s

Life Class, Bishop T.D. Jakes concluded, “It’s not a lack of love that stops an estranged father

from reconnecting with his child; it’s the fear of rejection.” Knowing that divorce could change

the dynamics of the nuclear family, some fathers are unaware of how to form stable relationships

with their children outside of the household. Bishop Jakes recommends that every dad needs to

“court” his child so that the lines of communication remain open. In the book Always Dad, Paul

Mandelstein (2006) advises divorced dads to find ways to stay relevant in their daughter’s lives.

He suggests that if divorced parents find a way to work together, father-daughter relationships

could potentially be saved. Although father-daughter relationships are often strained, throughout

history, substantial evidence has also been gathered on the effects that divorce has on father and

son relationships.

FATHER AND SON RELATIONSHIPS AFTER DIVORCE

A longitudinal study was conducted that tracked over 6,400 boys for more than 20 years.

Findings suggested that children who grew up in a household without their biological father were

more prone to commit crimes that led to incarceration (Harper and McLanahan 1998). Other

studies show that children of divorced parents are up to six times more likely to experience

delinquent behavior than children from intact families (Larson Swyers and Larson 1995). Boys

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

15

raised without their fathers were more than twice as likely to end up in jail as those who lived

with their fathers, and 70 percent of incarcerated adults come from single-parent homes (Georgia

Supreme Court Commission on Children, Marriage and Family Law 2004). In one study,

adolescents in single-parent and kinship families were “significantly more likely than

adolescents in intact families to report having been in a serious physical fight, shot, or stab

someone,” with the challenges of divorce for children are often manifested in their actions

(Franke 2000). Anger and frustration are key examples of the emotional and psychological

trauma that children of divorce face. These feeling are often connected to insecurities and fears.

The fact that a child who is of age has to witness their home fall apart can create levels of

uncertainty and fear about the future.

INCREASED CRIME RATES

In single-parent households, families often experience substantial financial distress

compared to married households (Garfinkel and MacLanahan 1986). Systemically, more mothers

are granted custody while fathers are granted visitation rights (Weitzman 1985). The rise in

divorced and single parent household’s rates has led to the accumulation of non-custodial fathers’

refusal to pay child support which has resulted in a $4-billion deficit in the U.S. In turn, the

change in economic stability frequently draws these families into more affordable but ‘bad'

neighborhoods (Wilson 1987). Demographically, these children attend schools where a high

number of students live in single-parent households and have significantly higher rates of violent

offenses than students attending schools where more students came from two-parent families

(Anderson 2002).

A policy brief completed in 2005 by the Institute for Marriage and Public Policy

(IMAPP), discovered that there is a significant decrease in both the individual risk and rates of

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

16

crime when children come from a two-parent household, indicating that a healthy family

structure and support are instrumental in the development of children’s overall behavior. A

family that can sustain divorce without making it problematic can enhance a child's ability to

perform better academically while encountering less juvenile delinquent behavior. The most

critical family characteristics that help youth avoid associations with delinquent peers are

parental supervision, care, and support (Kumpfer 1999). The figure below displays the overall

effects of divorce amongst juveniles:

Figure 5 . Juvenile Incarceration rates in Wisconsin for children of divorce

In 2007, law enforcement agencies reported 2.18 million arrests of juveniles. Juvenile

delinquent behavior is believed to be underrepresented due to the limited methods of collecting

data. Most reports are provided by the juvenile justice system and are based on juvenile justice

agencies’ self-reporting. Reports conclude that 16 percent of juvenile arrests involve violent

crimes such as murder, rape, and assault. Burglary, theft, and arson make up 26 percent of all

property crime arrests (Puzzanchera 2009). Other offenses include gambling, disorderly conduct,

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

17

weapons possession, illicit drug/liquor violation (including DUI) and prostitution. It is important

to note that some misdemeanor crimes go unreported while serious offenses involving injury and

substantial economic loss are reported more often.

It is estimated that $14.4 billion is spent annually on the federal, state and local juvenile

justice systems; this includes the costs of law enforcement and the courts, detention, residential

placement, incarceration and substance abuse treatment. However, this figure does not account

for the costs of probation, physical and mental health care services, child welfare and family

services, school costs and the costs to victims. It is estimated that combined spending on juvenile

justice could exceed $28.8 billion (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse,

Columbia University 2004).

Policymakers are beginning to recognize the link between family structure and juvenile

crime. An investigation into the cause of juvenile delinquency shows that there is an association

between family structure and the criminal behavior of these minors, even when socioeconomic

status is controlled. The Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 72 percent of jailed juveniles

come from a disintegrated family (Georgia Supreme Court Commission on Children Marriage

and Family Law 2005). A study conducted in Wisconsin found that the rate of incarceration of

children who parents were divorced was 12 times higher than children in two-parent families

(Fagan 2001). This does not imply that young people who are not incarcerated are not directly

affected by marital dissolution.

DEPRESSION AND YOUNG ADULTS

Depression amongst young adults was hypothesized by Drill in 1987; she addresses the

issue of depression amongst college students whose parents had divorced in the New York/New

Jersey Metropolitan area. Findings showed that these populations of students were more

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

18

depressed than peers from an intact home, which can ultimately have an adverse impact on the

college experience. Approximately 4,693 first-semester freshmen at a large, public university

completed a survey developed by the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP); they

answered questions about their behavior in high school, future goals, college readiness, and

expectations during their orientation in the summer of 2007. Based on their responses, the results

of a logistic regression analysis determined that those students who experienced parental divorce

have lower academic achievements during their first year of college. When conducting the

survey, several variables were considered, as indicated in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6 . Variables Included

SORIA(2014)

According to the results of the study, students who were victims of divorce had a notably

lower grade point average than their peers.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

19

Figure 7. First Year Students GPA

SORIA(2014)

Parental separation: effects on children and implications for services

When determining how many first-year students continue their academic journeys the

subsequent year, variables indicate that the likelihood of a college student of divorce returning

was reduced by 3 percent based on an 88.9 percent retention rate. Many studies have found that

based on demographic variables, pre-college academic indicators, college experiences, and

academic motivation control samples, it is clear that child victims of divorce, who are now

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

20

college students, have a harder time academically, financially, and mentally because of their

parents’ split (Aseltine 1996; Cartwright 2006; Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale and McRae 1998;

Christopoulos 2001; Laumann-Billings and Emery 2000; Wallerstein and Lewis 2004). Brackney

and Karabenick (1995); Kessler, Foster, Saunders, and Stang (1995); Kitzrow (2003) agreed that

divorce was a factor that could influence students’ academic achievement and retention. The

effects associated with divorce begin to change as one becomes an adult.

ADULT CHILDREN AFFECTED BY DIVORCE

As children moved into the adult phase, also considered the intimacy versus isolation

stage by researchers, those who are able to go through this juncture without conflict are known to

connect with others more effectively. Unfortunately, young adults who are children of divorced

parents have difficulty developing these skills, which could lead to isolation and loneliness

throughout adulthood. The relationships of young adults are directly correlated to what they have

witnessed as children (Erickson 1980).

“Erikson emphasized three elements of the capacity for intimacy: the willingness to make

a commitment to another person, ability to share at a deeply personal level, and capacity

to communicate inner thoughts and feelings. Individuals who favorably resolve the so-

called ‘Intimacy vs. Isolation’ psychosocial crisis is, then, high on these three

components. Isolation, at the opposite pole of the spectrum, is characterized by an

inability to commit, share deep feelings, and communicate.” (Kacerguis and Adams

1979)

These issues related to intimacy can continue throughout adulthood (Whitbourne, Sneed, and

Sayer 2008). Those adults who witness their parents’ divorce also experience emotional and

psychological effects that can impede their ability to sustain a relationship that requires intimacy

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

21

and companionship later (Duran-Aydintug 1997). When parents’ divorce while their children are

young adults, Erikson (1980) theorized that these young adults are extremely vulnerable to the

implication of divorce, which could hinder intimacy and may serve as a predictor for divorce in

their life. Thus, Erickson suggests that those individuals who can cope with any intimacy issues

as a young adult are often able to maintain stable marital relationships when they get older.

Conversely, young adults who are isolated are less likely to sustain a relationship, even if

they enter a marriage. Psychologist Albert Bandura’s theory on social cognitive and social

learning argues that a person’s individualistic behavior is influenced by environmental and

personal factors such as personal beliefs, and expectations (Corey 2009). To interpret the

relationships and attitudes of adult children who were victims of divorce, Segrin, Taylor, and

Altman (2005) applied the theory of social cognition to their research. They discovered that adult

children who had experienced their parents’ divorces were less likely to engage in long-term,

committed relationships because of the hostile environment they had endured as children. As a

result of observing contentious relationships between their parents, adult children learn from an

early age that marriage does not always lead to lifelong commitments and accept that divorce is

an option when marriage is unstable (Corey 2009; Segrin et al. 2005).

BLENDING OF FAMILIES

Although there is an increase in divorce and a high level of turmoil that is usually

associated with marital discord, remarriage and recoupling have become a common occurrence

in the United States (Ganong and Coleman 2004; Teachman and Tedrow 2008). This can result

in the children living in a household with a stepfamily (Mahoney 2008). Stepfamilies usually

exist after the dissolution of marriage or the death of a parent. In the past, marriage was often

required to define a stepfamily; in today’s society, people no longer see marriage as a

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

22

requirement to cohabit with someone you love. An increasing number of individuals have chosen

to live together as a family without the formality of marriage. The blending of families often

includes children from previous relationships. Depending on the custody arrangements following

divorce such change can be devastating to the children. The following terms are used to define

members of a stepfamily:

1. stepparent: a non-biological parent:

2. stepchild: a non-biological child brought into the family by marriage or cohabitation with

the biological parent

3. Stepsiblings (stepbrother, stepsister): siblings who are not related biologically, whose

parents are married to each other or cohabiting long-term.

An estimated 10 percent of children in the U.S are members of stepfamilies (Bumpass

and Raley 1995; Sweeney 2010). Research on stepfamilies has lagged considerably behind

research on divorce and is still a young area of study (Booth and Dunn 1994; Ganong and

Coleman, 1994; Jeynes 1997). In the United States divorce rates have been studied throughout

the years and the remarriage rates continue to rise (Amato 2010; Smock 2000; Sweeney 2010;

U.S. Census Bureau 2000). Could this be an indication that people like the idea of being

married? Studies completed by Heyman (1992) and Milne (1989) found that remarrying benefits

children from divorced homes, especially if the stepparent is of the same gender as the child, and

there are potential socioeconomic status increases. Other research by Amato and Keith (1991)

found that having stepparents creates different kinds of emotion, including; depression, lowered

self- esteem, and anxiety in children. Many children experienced internalized, externalized, and

academic issues, combined with risky behavior (Coleman, Ganong, and Fine 2000). In order to

understand how children are affected by divorce and their subsequent stepfamilies, a study of

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

23

1,088 children between the ages of ten and sixteen was conducted. The study examined the

relationship between the child (ren) and their step-parent. The purpose of the survey was to

provide clinical insight, on the positive outcomes of stepfamilies while evaluating how the roles

and characteristics of stepfamilies help shape the child (ren) (Cherlin, 1978, 2004).

Three research questions were addressed:

1. Will the role of the family contribute to an increase in stepfamily relationship-quality for

children?

2. Will parental-subsystem characteristics increase levels of stepfamily relationship quality

for children?

3. What resources will contribute to an increase in stepfamily relationship quality for

children?

According to research findings, as long as a divorced mother ensures the needs of her children

are met, and the lines of communication remain open, children will be able to transition into the

new family dynamics smoothly. When children witness a harmonious relationship between their

parent and step-parent, they tend to have a healthy relationship with their step- parent. In a 1981

national study of stepparents and stepchildren, each was asked who they considered a family

member. The kids were between the ages of eleven and sixteen, so they were acutely aware of

the questions being posed. 15 percent of the parents who had stepchildren did not include them

as family, while 31 percent of the children who had a stepfather did not include them in the

process either (Furstenberg 1987). Marsiglio (1992) believes these percentages have a lot to do

with the ages of the children when they became a part of a stepfamily. Younger children tend to

be more responsive to the idea of a stepfamily, making it easier to establish a relationship.

Secondly, the role that the non-custodial parents play in the child’s life can determine the

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

24

stepparent–child relationship. The study has shown that the stepmother and child relationship can

be harder to achieve than the stepfather and child relationship (White 1993).

Ideally, stepmothers are often trying to fit into a role that has already been filled by the biological

mother and because many children of divorce often live with their mothers following divorce

makes it can be difficult for the stepmother to find a comfortable place to fit in. On the other

hand, fathers are usually the non-custodial parent, and the child may have less interaction. In the

event the biological parent is not around, then the child may be more willing to accept greater

involvement by the stepfather. Lastly, Marsiglio believes that the temperament of the child is

also a key factor.

In addition, there has also been some concern in regards to the level of sexual abuse that

children of stepfamilies experience. Reported cases suggest that stepfamilies have higher

percentages of physical abuse, homicide, neglect, and injuries than in two-parent households

(Burgess and Garbarino 1983; Daly and Wilson 1981,1985,1987,1991 Gil 1970; Giles-Sims and

Finkelhor 1984, Kimball, Stewart, Conger and Burgess 1980; Wilson, Daly and Weghorst 1980).

In a retrospective study, 17 percent of girls were sexually abused by their primary stepfathers,

and those rates are significantly higher amongst stepfathers who were not considered a primary

caregiver (Russell 1984). The study suggests that these acts of violence that are committed have

a lot to do with the predator’s socio-economic background, drugs, alcohol and of course mental

instability.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

25

Figure 8. Sexual Abuse by Family Structure

“Margo Wilson and Martin Daly (2012) professors of psychology at McMasters

University, Canada, reported that children two years old and younger are 70 to 100 times

more likely to be killed at the hands of stepparents than at the hands of biological parents.

(Younger children are more vulnerable because they are so much weaker physically)”.

Although many studies used remarriages and children’s academic performances as

metrics for comparing the achievement of divorced families, these studies are relatively new and

do not give definitive information because there several variables to consider, such as the length

of time and quality of the remarriage (Heyman 1992; Milne 1989). National Education

Longitude Surveys (NELS) for the years 1988, 1990 and 1992 were analyzed to examine the

social economic status (SES) and achievement gaps of those students whose parents remarried.

In the 1988 study, over 24,000 8th-grade students from 1,052 schools participated in the surveys.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

26

Questionnaires were given to the children, parents and the teachers on external behaviors,

academic performance, and classroom conduct, while achievement tests in math, reading,

science, social studies, history, civics, and geography were given to students. These tests were

“curriculum-based cognitive tests that used item overlapping methods to measure" academic

achievement (U.S. Department of Education 1992). The studies had some inconsistencies. The

1990 study did not include the SES of children, while the 1992 study placed all students in the

same household category, without distinguishing the type of households they lived in. The 1988

data, however, did provide more detailed information. This analysis involved looking at

academics from a broader perspective. Eighteen categories were created, and students were

matched by three variables: (1) family structure (intact, divorced and remarried, and divorced

single-parent); (2) race (including Black, Hispanic, and White children); (3) SES (low SES/lower

50th percentile or high SES/higher 50th percentile). The analysis showed that those children

from stepfamilies have higher SES, but have a lower level of achievement than those from

divorced single-parent homes. In fact, data reveals that remarriage might have an adverse impact

on academic performance of middle school kids, especially in math. Although researchers

continue to look at the SES status as a happy median for reconstituted families, the academic

success rate shows distress. This study showed that students whose parents remarried did not do

as well as students whose parents had remained married (Jeynes, 1988).

FATHERS AS THE CUSTODIAL PARENT

Although there is literature available regarding stepfamilies, more and more fathers are

obtaining custody of their children. Between 1970 and 1990, the number of single dads raising

children alone increased from 275,000 to 1,355,000 (Greif 1987). A study conducted by the

Whirlpool Corporation found that 88 percent of women surveyed agreed that it is a mother’s

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

27

responsibility to take care of their members of the family” (Families and Work Institute 1995)

and non-custodial moms that don’t are often ostracized and considered incompetent because of

the traditional role of mothers. A study of 38 mothers who did not have custody of their children

by Todres (1978) found that each mother was emotionally unstable due to their inability to

financially provide support to their child(ren). When couples are married, they often work

together to ensure the family is financially secure. Zagorsky completed a study of Americans in

their 20s, 30s, and 40s, and found that those who were married had a higher net worth than those

who were single (Zagorsky 2005). Zagorsky identified three economic beliefs that underlay

marital and financial success:

1. People who form a life together often invest more in their future, especially if they intend

to raise a family.

2. Married couples often divide financial responsibilities. The two incomes make it easier

for each person to pay their share and save.

3. An agreement that describes the role of each partner is usually developed between

married couples, ultimately leading to cohesiveness and solidarity.

Once it is determined that the relationship is severed, former couples must decide on the

division of assets, including the home, any vehicles, and investments. Many former couples find

it difficult to come to an agreement on who gets what. Other painful compromises are often

necessary when children are involved such as co-parenting, custody, and visitation (Scott 2010).

In the most common cases, the father lives away from the family and supports his ex-wife and

their children. According to records on child support, most fathers continuously fail to pay child

support. The failure to pay child support by some fathers has forced some mothers to become

non-custodial parents. Economic instability, which results from divorce, is one of the leading

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

28

causes of women rescinding their parental rights (Albrecht 1980; Peterson 1989; Reissmanm

1990; Weitzman 1985). Especially if a woman was unemployed before the divorce and decides

to go to work after divorce, she may have considerable difficulty entering the job market. She

may not be lucky enough to find a job that pays enough to sustain her household (Albrecht 1980;

Weitzman 1985).

Herreria (1995) conducted a study of 130 mothers that found that the mothers’ emotional

instability and financial insecurities were the primary reasons for their noncustodial status.

Fischer and Cardea (1981) interviewed 17 mothers who believed that their children were "bought

off" by fathers who often provided their children with gifts that would encourage the children to

agree with them in some cases. In a study of 517 mothers by Greif and Pabst (1988) they found

that money and emotional instability were reasons they did not have custody of their children.

Additional reasons included children choosing to live with their fathers, court decisions, a

mother pursuing a career, a father pressuring his children or their mother, or a father abducting

his children. More than half of the mothers in Todres's study experienced shame and guilt, and a

few reported lying when asked about their custody situation. Herreria (1995) noted that

following the relinquishment of custody, 80% of the mothers cried for days and weeks. Greif and

Pabst (1988) reported that the mothers in their study reported that being a noncustodial parent is

stressful.

Over the course of time, one-third of the mothers felt comfortable and one-third felt

uncomfortable, while one-third had mixed feelings about their noncustodial status. Three studies

found that many non-custodial mothers visited their children at least once a month— Herreria

(1995) found that 50 percent visited; Greif and Pabst (1988) reported that 63 percent visited, and

Furstenburg et al. (1983) found that 69 percent visited. Distance, remarriage, and lack of interest

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

29

are all factors responsible for these sporadic visitations. Some noncustodial mothers may make

visitation emotionally difficult for their children if they seek information about the fathers of the

children, ultimately making the children feel guilty. Those who voluntarily turned over custody

were, for the most part, better adjusted.

In addition, noncustodial mothers are less likely to be court-ordered to pay child support

because most mothers lose custody due to lack of income. Furthermore, when fathers are ordered

to pay child support, some refuse to pay their ex-wives. Fathers may decline payment from their

children’s mother because they believe she cannot afford it (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1995).

DEPRESSED MOTHERS AND THE EFFECTS ON THE CHILDREN

The fear that a mother is unable to provide for her family can lead to excessive anxiety,

anger, and resentment. It can bring forth emotions that are difficult to handle and can result in

depression, social isolation, and health issues. During and after a divorce, parents can experience

an array of problems. Sometimes these problems can affect them mentally and how parents

handle these problems determines how stable their relationships with their children will be.

In the United States, over 20 million people have been diagnosed with a mood disorder.

Those who experience the hardship of divorce have a higher degree of depression and bipolar

disorder than those who do not (Kessler, Chiu, Demler and Walters 2005). Because these

disorders have been recognized as a contributor to mental instability during and following a

divorce, there have been considerable studies on the illness.

Depression contributes to 30 percent of marital dissolutions and has a direct effect on

each party (Gotlib and Hammen1992) and often leads to marital dissatisfaction. Anyone can be

diagnosed with depression and mood disorder; depending on the severity of the illness it can

cause persistent feelings of sadness and apathy. Depression affects people’s emotions, how they

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

30

feel, think, and handle daily activities; sometimes, these individuals even lack the desire to

interact with other people. The illness can lead to a host of other emotional and physical

problems, which require long-term treatment. Most people with depression use medication, or

psychological counseling to manage the illness (mayoclinic.org). Depression is often triggered

by a chain of events that are emotionally and psychologically overwhelming. When this occurs

within a marriage, rather than sympathizing with their partner, spouses often feel angry,

discouraged, and stressed as they witness their partner becoming more distant, hopeless, and

tired; these individuals often lose interest in social interactions, as the symptoms become more

recognizable and increase over time (Rosen and Amador 1996). Rotermann (2007) conducted a

study over a two year period using longitudinal data from the National Population Health Survey.

Examining how marital discord is directly associated with depression amongst Canadians

between the age of twenty and sixty-four. Results determined that women of divorce are more

likely in the two years following their divorce to be depressed than married women.

Whereas divorced men had six times the occurrence of depression when compared to men who

remained married.). “Nationally representative cross-sectional and longitudinal studies from the

United States and Europe suggest that, compared with people who remain together, those who

have experienced marital breakdown are at increased risk of mental health problems.” Symptoms

include:

1. persistently sad, anxious, or “empty” mood (or just feeling numb);

2. feelings of hopelessness and pessimism

3. the sense of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

4. children were once enjoyed but less so when depressed

5. decreased energy, fatigue, being “slowed down.”

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

31

6. difficulty concentrating, remembering, and making decisions;

7. insomnia, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping;

8. appetite or weight loss or, conversely, overeating and weight gain

9. thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide attempts;

10. restlessness or irritability;

11. persistent physical symptoms that do not respond to treatment, such as headaches,

digestive disorders, and chronic pain

According to Weissman and Paykel (1974), the emotional and psychological discord a

mother goes through during depression could interfere with her mother-child relationship.

Depressed mothers have little ability or desire to be active parents or to supply their children

with the emotional support they need (Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1988). A depressed

mother usually shows little or no interest in disciplining her children or having discussions about

the consequences of misbehaving and the mother is often dismissive when the unruly behavior

occurs (Kuczynski 1984). Bonding is also difficult for a mother who is dealing with depression.

They tend to be irritable and hostile toward their children (Cohn, Campbell, Matias and Hopkins

1990). Therefore, when dealing with a parent who suffers from severe depression, it is important

to be aware of any signs that may signify child abuse, and whether or not the parent can use

additional help. In a report by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, when a

mother experiences depression while raising her children, her children are more likely to feel the

effects of her illness starting at infancy (Beardslee, Versage and Gladstone 1998).

According to the study, due to her inability to bond with the infant, the baby may cry

more than other babies, have a greater fear of strangers, and could be easily frustrated. Moreover,

when entering preschool, some children who have mothers who suffer from depression are more

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

32

likely than their classmates to have an attention-span deficiency. The NIMH’s longitudinal study

showed that in five to seven year-olds, 64 percent of the older children and 55 percent of the

younger children showed either depression, anxiety, or a disruptive behavioral disorder. Fear was

present in one-third of children aged eight to eleven (Radke-Yarrow 1998). This study brings

awareness of the psychopathological effects that depression has on children whose mothers

suffer from the deadly disease. The symptoms that come with depression, such as mood

disorders, bizarre thoughts, or lack of self-love, just to name a few, can easily be passed down to

their offspring. Research suggests that during the processes of depression and divorce, it is

important that parents have an open conversation with their children and inform them about what

is happening while encouraging them to express their fears and emotions about the processes

(Taylor 2001 Andrews 2002). Symptoms of depression should be discussed so that children are

aware it has nothing to do with them. They should understand that it is a sickness that cannot be

fixed overnight but should also be reassured of their parents’ unconditional love for them. Lastly,

they should strive to have healthy relationships with their peers and other adults to assist with

coping (Andrews 2002, 2003).

ADOPTED CHILDREN AND DIVORCE

Most research looks at divorce from a biological or remarriage aspect. Unfortunately,

adopted children may also experience an array of emotions that are common in family discord.

Despite a significant amount of research conducted regarding children of divorce, there is still a

robust debate concerning the effects divorce has on adopted children.

The National Survey of Families and Households analyzed five types of households with

different family structures. The study investigated the relationship and well-being of children

who live in the home with adopted parents, single mother, biological parents, stepfathers, and

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

33

stepmothers. Some researchers have found that adoptees often experience higher levels of

academic difficulty, problematic behavior, and psychological instability, along with other

symptoms (Haugaard 1998; Wierzbicki1993). Other studies suggest that there are no significant

differences in the behavior of any population of children or adolescents (Borders, Black, &

Pasley 1998). Because of society, a stigma has always been attached to parents who adopt. Some

people believe that adopted parents are often unable to love their adopted children because they

did not actually give birth to them and may question the authenticity of the parent-child

relationship (Miall, 1987).

Recently the Search Institute surveyed a random sample of 1,262 parents, 881 adopted

adolescents, and 78 non adopted siblings and found that 74% of the adopted adolescents reported

positive family dynamics (Benson, Sharma & Roehlkepartain 1994). No variation could be found

among either population of children, and adoptive parents did not show any sign of increased

family dysfunction. However single-parent households seemed to have the least adaptive family

structures due to life challenges, which include unequal economic growth and lack of emotional

support compared to their peers.

The National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH; Sweet & Bumpass, 1996)

included 799 families. The sample examined five different family types. In one family type, the

child in the home was at least one eighteen years of age who resided with both biological parents.

The sample also included (a) married couples who had at least one adopted child eighteen years

of age or younger (b) biological children who lived with both biological parents.

(c) single unwed mothers due to divorce with biological children only; (d) biological mothers

who remarried and the husband was the stepfather to one of the children; (e) biological fathers

who had remarried with a wife who was the stepmother to at least one of the children. Reports

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

34

from each participant were evaluated separately. Depending on the family structure of the

participants, information was gathered from two parents in a household, and their child, from one

parent, from both parents, or from one parent and a child. The assessment measured parents’

well-being paying close attention to any recently depressed emotions that they might have

experienced using a rating scale. Child well-being was also viewed from the parent’s perspective,

taking into account if the child had ever been suspended, academic success rates, criminal

activities, and the level of self-esteem, behavioral issues and quality of peer relationships. The

children were also asked if they indulged in any drug use, smoked cigarettes, skipped school and

engaged in fights with peers. Parents were asked how well their children got along with other

family members, while the children also discussed their views on family, how much their parents

knew about their overall life and their views on marriage and having children. The quality of the

parent’s spousal relationship (understanding, love, and affection, time together, demands, sexual

relationship, money, work around the house, parenthood) was also considered.

Figure 9: Adoptive mothers reported that their child had higher levels of internalizing and

externalizing issues, and they experienced more disagreements with their children than mothers

in two-parent biological, stepfather, or stepmother households.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

35

Figure 9. Constructs Reported by Mother

Figure 10: Biological fathers in two-parent household had closer bonds and spent more time

with their children than fathers in other groups. Nonetheless, there was no evidence that families

with other structures showed any signs of trauma.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

36

Figure 10. Constructs Reported by Father

Figure 11. Showed that those children who lived with their mothers, adoptive, two parent

biological households, or stepmothers had better relationships than those children who resided

with stepfathers. Those children who were in adoptive families were the only population that

looked forward to being married and having children in the future.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

37

Figure 11. Constructs reported by Child

CHILDREN WHO LIVE IN SWEDEN

Sweden provides an interesting contrast to the United States regarding the effects of

divorce and varied family structures. Nearly 60 percent of children in Sweden between the ages

of thirteen and fifteen live in two-parent households. However, the parents in 30 percent of

divorced families share joint custody (Demografirapport 2007:4. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden,

2007). Researchers now see shared custody as a healthy way to co-parent (2010 Stockholm

Statistics Sweden).

Europeans believe that in cases where parents have lower levels of conflict during and

after a divorce children often benefit from shared custody because it gives them the ability to

have both parents in their lives, but research shows that it is not as beneficial when parents have

elevated levels of dissension (Kelly JB; Emery 2003).

One study determined that 26 percent of children whose parents shared custody had a

higher rate of alcohol and drug abuse compared with adolescents from two-parent families.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

38

In a cross-sectional design, the behavior of 3,699 school-aged ninth grade adolescents from

Sweden was evaluated in an attempt to determine the direct effects of divorce in situations of

shared custody. Children were grouped into three categories: they (a) lived with both parents,

(b) parents shared custody, or (c) they lived in single parent households. A series of questions

was asked about the children’s living arrangements, family structure, parent’s economic-

employment status, and the stability of the parent/child relationship.

Carlsund, A., Eriksson, U., Lofstedt, P., & E. S. (2013). Risk behaviour in Swedish adolescents: is shared physical custody after divorce a risk or

a protective factor? p.5

1. Adolescents who did not live with both biological parents were prone to smoke at a

higher rate (24.1%, 19.8%) than those adolescents living in two-parent families (13.5%).

2. Adolescents in single-parent families had a much higher rate of drunkenness (51.1%)

than those in shared physical custody families (46.2%) and two-parent families (34.4%).

Figure 12. Control and Outcome Variables

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

39

3. Sexual interaction took place at a younger age and was more prevalent among

adolescents in single-parent families (40.9%) and shared physical custody families (30%)

than in two-parent families (25.5%)

4. Conduct issues amongst adolescents living in single-parent families were higher (22.9%)

than those living in shared physical custody (17.4%) and two-parent families (16.1%).

Figure 13.Risk Behaviors and conduct problem

Carlsund, A., Eriksson, U., Lofstedt, P., & E. S. (2013). Risk behaviour in Swedish adolescents: is shared physical custody after

divorce a risk or a protective factor? p.5

1. Model 1: found that adolescents who lived in parents shared custody homes, or single

parent homes had a higher chance of becoming a smoker compared to those who lived in

two-parent households. The study also found that girls who had a strained relationship

with their mothers or had difficulty economically were more likely to smoke.

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

40

2. In Model 2: adolescents whose parents shared custody and those who lived in single

parent households were more prone to partake in drunken behavior. Teens in shared

physical custody, or in single-parent families along with those teens who found it difficult

to talk with either parent, seemed to have an increased number of drunken behavioral

episodes.

3. In Model 3: although there were no significant differences in the sexual experience of

those adolescents in two-parent households or shared custody homes, the study did show

that those in single parent households usually engaged in sexual activity by the age of

fifteen.

4. Compared with adolescents from two-parent families, adolescents living in shared

physical custody were not at a higher risk for conduct problems, whereas adolescents

from single-parent families had a higher level of conduct problems. Families who have

financial stability have fewer behavior issues than families with lesser economic means.

Adolescents who reported difficulty talking to their fathers and mothers were more at risk

of having conduct problems.

It is evident that divorce is universal and that all kids go through some level of discomfort when

their parents decide on marital dissolution. Based on the research from Sweden, joint custody is

seen as a positive experience for children. However, shared custody seems to be less beneficial

when children experience their parents' relationship as highly combative and thus the benefits of

shared custody remain in dispute. (Kelly and Emery [2003]: 352-62).

Overall, there is limited evidence to support the theory that the family structure of

adopted children is less gratifying than that of biological parents who reside with their biological

offspring. Mothers of adopted children confirmed that apparent issues do exist, while biological

CHILDREN OF DIVORCE

41

mothers had more disagreements with their children than stepmothers or stepfathers while

adoptive parents still spent more quality time with their kids. Although two parent households

are favorably viewed within society, children in single parent households did not have

significantly more problems with their relationships or well-being. Biological mothers and

stepmothers both agreed that their kids had fewer behavioral problems, while the amount of time

they spent with their children was identical to adoptive parents. There were no major differences

in the children’s academic preparedness and relationships with family members. Overall, the

research demonstrated that family structure is not necessarily a factor when evaluating

someone’s well-being and the quality of relationships. Once again, the level of conflict that

children experience in the home emerged as the common denominator when discussing their

overall development.

CONCLUSION

After a divorce, a mother must learn to co-parent with her ex-husband while adapting to

the loss of her role as spouse and often as the primary caretaker. Mothers who willingly give up

custody can reconnect with their children; they adjust psychologically to the custodial situation

more quickly, with less animosity toward the father. If the breakup was rancorous, this task is

challenging. Moreover, the most common problems that arise relate to child support, visitation,

property division, remarriage, and the rearing of the children. In some cases, allegations or

histories of child abuse or domestic violence will taint the parents' ability to co-parent. Research

indicates that if the father-mother relationship is successfully resolved, the father is likely to find