Michigan Technological University Michigan Technological University

Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech

Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports

2020

Through Her Eyes: The Gendering of Female First-Person Through Her Eyes: The Gendering of Female First-Person

Shooters Shooters

Elizabeth Renshaw

Michigan Technological University

Copyright 2020 Elizabeth Renshaw

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Renshaw, Elizabeth, "Through Her Eyes: The Gendering of Female First-Person Shooters", Open Access

Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/1045

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etdr

Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the

Other Film and Media Studies Commons

THROUGH HER EYES: THE GENDERING OF FEMALE FIRST-PERSON

SHOOTERS

By

Elizabeth Renshaw

A DISSERTATION

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

In Rhetoric, Theory and Culture

MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY

2020

© 2020 Elizabeth Renshaw

This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Rhetoric, Theory and Culture.

Department of Humanities

Dissertation Advisor: Stefka Hristova

Committee Member: Carlos Amador

Committee Member: Adam Crowley

Committee Member: Diane Shoos

Department Chair: Scott Marratto

iii

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ vi

Abstract .........................................................................................................................vii

Through Her Eyes: The Gendering of Female FPSs ......................................................... 1

Press Start ............................................................................................................... 3

Her-story ...................................................................................................... 4

Tutorial............................................................................................................................ 7

Terminology ........................................................................................................... 7

Gameplay ..................................................................................................... 7

Mechanics 8

Dynamics 9

Affects 10

Narrative ..................................................................................................... 10

Methodology ........................................................................................................ 12

Ludonarrative Synchronicity ....................................................................... 13

Insert Coin ............................................................................................................ 16

Is the game a first-person shooter? .............................................................. 17

Is the female avatar given, not chosen? ....................................................... 19

Was it produced by a “AAA” studio? .......................................................... 22

The Rise (1991-95) ........................................................................ 23

The Dead Zone (1996-2001) .......................................................... 24

The Peak (2002-09) ....................................................................... 25

The Collapse (2010-2018) ............................................................. 25

Literature Review ................................................................................................. 26

Female or Feminine?................................................................................... 27

Cyborgs 28

Plurality of Identities................................................................................... 31

Straight to Video (Games)........................................................................... 32

Gamer’s Gaze ................................................................................ 33

Point of View ............................................................................ 34

Chapter Preview ................................................................................................... 36

Level One: Svelte Spies .............................................................................. 36

Level Two: Alien Queen(s) ......................................................................... 37

Level Three: Bullet (Free)-Time ................................................................. 37

Boss Battle .................................................................................................. 38

Level One: Spy vs. Spy ................................................................................................. 39

Svelte Spies .......................................................................................................... 39

iv

Jane Bond ............................................................................................................. 42

Perfect Dark ......................................................................................................... 45

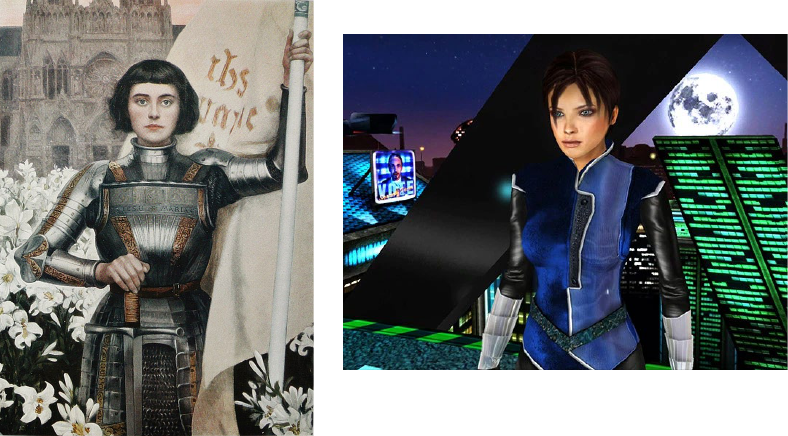

Joan of Dark ............................................................................................... 45

The Clothes Make the Woman .................................................................... 47

The Operative: No One Lives Forever................................................................... 50

Sexy Sixty’s Spies ...................................................................................... 51

Dressed to Kill ............................................................................................ 52

Scent of a Woman ....................................................................................... 53

Femme Fatales ...................................................................................................... 55

Level Two: Alien Queen(s)............................................................................................ 59

Brains over Brawns ............................................................................................... 59

Previously On… ................................................................................................... 60

Metroid Prime ...................................................................................................... 62

The Last Bounty Hunter .............................................................................. 63

The Right to Look ....................................................................................... 65

Irreplaceable ............................................................................................... 66

Alien: Isolation ..................................................................................................... 67

Last (Wo)Man Standing .............................................................................. 68

Like Mother, Like Daughter ........................................................................ 69

Bulletproof.................................................................................................. 70

Space Sirens ......................................................................................................... 72

Level Three: Bullet (Free)-Time .................................................................................... 73

I Am No Man ....................................................................................................... 73

Violent Femmes .................................................................................................... 74

Portal 76

Eyes Without A Face .................................................................................. 78

Ghost in the Chell ....................................................................................... 80

The Cake is a Lie ........................................................................................ 83

Fe-Male 84

Mirror’s Edge ....................................................................................................... 85

At the Edge ................................................................................................. 85

Follow the Ruby Piped Path ........................................................................ 87

Reload 89

Jump Around ........................................................................................................ 91

Boss Battle .................................................................................................................... 93

License to Kill ...................................................................................................... 93

v

Guns Don’t Kill People, Girls Do ......................................................................... 94

No Men Were Harmed in the Making of This Game ............................................. 95

Dodge, Duck, Dip, Dive, & Dodge ....................................................................... 98

Dead End .................................................................................................... 98

Antagonist Instincts .................................................................................. 100

The Future is Female .......................................................................................... 105

Wolfenstein: Youngblood .......................................................................... 105

Half-Life: Alyx .......................................................................................... 106

To Be Continued… ................................................................................... 107

Reference List ............................................................................................................. 108

A Copyright documentation .................................................................................... 117

vi

Acknowledgements

To Laura, you know what you did.

vii

Abstract

While the video game industry has attempted to address their years of mistreatment

towards women, within games and how they are produced, by hiring more women and

including more female characters as playable options, these fixes have been superficial at

best. Not only are there still few females as main characters in video games, but that there

are so few female video games. By this I refer to the fact that video games told through

the eyes of female characters often do not feature a gendered narrative, unlike multiple

games with male POVs in which the storyline directly reflects their gender. This issue,

however, is not just about inclusion of more female stories, but also execution. Female

FPSs may lack a narrative reflecting their gender, but they often feature gameplay that

represents a stereotype of females as weaker and less aggressive than men. The purpose

of this analysis is to explore how first-person shooter video games gender (or not) their

female texts, through both narrative and gameplay.

1

Through Her Eyes: The Gendering of Female FPSs

Imagine waking up in a bunker, your hands cuffed to a rusty bedpost. A man stands in the

corner with his back turned. Another sprawled on the floor, dead. The first man turns

towards you and begins to spout doomsday prophecies. This is Joseph Seed, the cult

leader of Eden’s Gate. His prediction of a “world on fire” has come true as moments

before numerous nuclear bombs were detonated around the globe. Joseph leans over you,

with a cold, intense stare (Figure 1). His gaze, constructed through a low angle, is

intimidating and threatening.

Figure 1

Joseph utters: “You’re all I have left now. You’re my family. And when this world is

ready to be borne anew, we will step into the light. I am your Father and you are my

child. And together, we will march to Eden’s Gate.”

2

As the world above crumbles, both literally and figuratively, the ceiling florescent lights

in the bunker dim casting even darker shadows on Joseph’s face and, leaving you alone

with him and his smirk. Harnessing the visual conventions of film noir where hard light is

associated with masculinity, this psychological thriller game recreates a sense of danger

embedded in both patriarchy and patriotism. This is just one of three endings players can

experience upon completing Far Cry 5 (2017), a first-person shooter game set in rural

Montana. You play as an unnamed deputy who, along with two US Marshals and the

county sheriff, is dispatched to arrest the cult leader, Joseph Seed. Unlike previous games

in this franchise, players can customize the deputy based on gender, skin color, hair

options, and clothing. These choices result in small changes throughout the game, such as

what pronouns are used to address your avatar or how low-pitch your death rattles are,

where the available pronouns are he and she and the pitch is articulated along gender

lines with high pitch representing a feminine avatar and a low pitch signaling a male

avatar? None of these alterations, however, are meant to alter the plot. Whether you

choose male or female, white or black avatar, the implication is that you’ll experience the

same story. Regardless of your avatar, the ending has you locked in a bunker with John

Seed, waiting however long the half-life of a nuclear bomb is to see the light of day

again. If you have chosen to play with a female avatar, there is far greater horror &

suffering awaiting you. Joseph craves company, the power-trip from being worshiped,

and most of all he desires family. The potential for rape is not directly implied by the

game’s developer Ubisoft, but that is this ending’s very problem. The game does not

formally acknowledge that that gender matters in the players experience of what is

assumed to be a uniform and universal plot. Far Cry 5 is exemplary of the complicated

3

ways in which gender is engaged in the production, representation, as well as play of

First-Person Shooter (FPS) games.

Press Start

In 2017, the Entertainment Software Association (ESA) released its report on sales,

demographics, and usage data in the computer and video game industry. According to the

ESA’s findings, “women age 18 and older represent a significantly greater portion of the

game-playing population than boys under age 18,” and women of all ages make up 42%

of the overall game-playing population (2017 Essential Facts About the Computer and

Video Game Industry 7). Unfortunately, the gaming industry has yet to recognize this

growing audience. According to the International Game Developer Association (IGDA),

only 21% of game developers have a world-wide identity as women (Developer

Satisfaction Survey 2017 Summary Report). Misogynistic crusades such as #GamerGate,

lack of representation within the industry and the sexual harassment suffered by the few

women employed have hampered the growth of female portrayals within games and

contributed to a masculine gaming culture. Within video games, all too often females are

seen as Other or are rendered invisible. They are consistently used as expendable avatars

or characters to be gawked at as mere objects of curiosity. Female avatars are positioned

as powerless damsels in distress in need of saving, as overly loquacious companion in

need of silencing, or as bosomed temptress to tame or kill. If female avatars are seen as

defenseless others, straight, white males are deemed as capable and thus playable. Not

only are there still few females as main characters in video games, but that there are so

stories few told through the eyes of female characters.

4

Developers have failed to recognize implicit and explicit gender differences. Even

on the few occasions, when FPSs feature a sole female character, these games often lack

a gendered narrative or gameplay, unlike multiple games with male POVs in which their

gender affects both the narrative and gameplay. This issue goes beyond just video game

creators, but to the very scholars who studied these texts. Aubrey Anabele, in her book

Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect, laments how game studies “seems to

want to move beyond the still-important question of representation by figuring a

computational realm in which power works in ways that are detached from lived

experience and, hence legible only to those with the power to decipher them (56).

This issue of recognition is not just about inclusion, but also execution. In this

dissertation, I explore how first-person shooter video games gender (or not) their female

texts, with gameplay and narratives that references the protagonist’s gender. In talking

about gendering female FPSs, I use “gender” as a verb. To gender is to code, to

internalize, to produce a narrative and gameplay that “becomes essential to the formation,

persistence, and continuity” of the subject’s gender designation (Butler The Psychic Life

of Power: Theories in Subjection 3).

Her-story

Female characters, in general, have had less than dignified treatment within video

game texts themselves. More often than not, female figures in games are limited to non-

playable characters (NPCs) in need of rescuing, protecting, or killing (Summers and

Miller 1030). Tracy Dietz’s analysis of video game violence and gender roles found that

games were filled with princess and damsels in distress with “21 percent of the games”

5

analyzed portraying females as victims” or in other words in positions lacking power.

(Dietz 435). This study, however, only covers video games up until the late 90s.

Subsequently, this trend has evolved to position female characters who possess agency,

some ability to control their actions, as a threat that needs to be visually consumed or

eliminated: “recent female video game characters are not only found to be sexy, but also

aggressive.” (Summers and Miller 1030). Summers and Miller note that “Options for

playable female characters are limited to gamers and, when available, she will most often

be impractically masked and armored for gamers’ visual pleasure.” (Summers and Miller

1028). For every battle-suit wearing Samus Aran, there is a Bayonetta with her black

catsuit and bouncing boobs. Female characters are thus often positioned as objects to be

looked at and to be conquered. The visual pleasure here is derived through the

objectifying gaze of the male characters as well as the presupposed male game player,

where the gaze is endowed with power and agency.

First-person shooters have underutilized the use of women as the main character

more than any other genre of video games as approximately only twenty percent include

females at the forefront (Hitchens). In 1994, Rise of the Triad and Zero Tolerance were

the first FPS games where the player had the option, but was not forced, to play with a

female avatar (Ibid). In 1998, the expansion pack Star Wars Jedi Knight: Mysteries of the

Sith replaced Kyle Katarn with Mara Jade thus giving the option to play a female main

character. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that mainstream FPS games featuring a female,

6

and only a female, lead became available.

1

In a survey of over four hundred FPSs

conducted in 2011, Michael Hitchens found that eighty-one percent of FPS had the

gender of the main avatar enforced as male. Nineteen percent of games featured a female

avatar as enforced, optional, or gender unspecified. Finally, only four percent of the

games overall had the female avatar enforced (Hitchens). However, even when females

are at the fore-front of the character articulation, their gender is not always reflected in

the gameplay and/or narrative.

1

Perfect Dark & The Operative: No One Lives Forever

7

Tutorial

. Defining terms is tricky. There is an unspoken assumption behind the practice: that if a

definition is correct-if it manages to capture the essence of the thing under discussion-

then everything that logically follows from that definition will be correct too. And so

scholars often take great pains to demonstrate that there is a strong correlation between

their definitions and reality.

The “correction” of a definition isn’t a property of the relationship between the word and

reality; it is a function of the conversation that the definition facilitates. And, indeed,

multiple contradictory definitions can all be equally “correct” if they each manage to

independently structure a producing discourse (Upton 12).

In assessing the ways in which FPS games are gendered, this dissertation explores how

does the narrative of these games represent the protagonist’s gender? What kind of

gameplay can evoke the protagonist’s gender? And does the narrative and gameplay

reference the same gender? In order to answer these questions, I will first define two key

terms: gameplay and narrative.

Terminology

Gameplay

In the analysis, I harness definition of gameplay established by Robin Hunicke, Marc

LeBlanc, & Robert Zubek and their concept of MDA (mechanics-dynamics-aesthetics).

Their lecture series, “MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research,”

8

presented over several years at the Games Developer Conference was intended as a

methodology to be shared by scholars and developers alike. For LeBlanck and Zubke,

gameplay consists of mechanics, dynamics, and affects.

Mechanics

Mechanics are the ludus of a game, that is the rules at play. They refer to all necessary

pieces that one needs to play the game, including the equipment, the venue, or anything

else necessary for play to be had. In considering the game as a system, the mechanics are

the complete description of that system. Another way to consider mechanics is as a

“system of constraints” (Upton 15). Designer and scholar Brian Upton, building upon the

work of academics Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, explains that the rules of a game

(not just video games) are a system of constraints, a varied group that can include:

the physical geometry of a level, or the behavior of the enemy AI, or the amount

of damage that a hand grenade does… Anything in the game that proscribes the

player’s ations is a constraint. The player is free to move around within the game

world, to trigger actions, even to change the world’s configuration, but always

within limits laid down by the game itself (Upton 16).

But mechanics do not need to be constraining. Take for instance a game like Borderlands

(2009), a bizarro sci-fi FPS set on the perilous planet Pandora, filled with kooky

characters, and even crazier physics. In the game, players take control of a Vault Hunter,

inter-planetary mercenaries with little regards to the rules or laws. As such, the laws of

9

physics in the game are nigh non-existent.

2

For instance, when a player falls from a great

height, despite the hard impact, there is no loss of health. The lack of damage, a

cartoonish effect in a game filled with outlandish aesthetics, is a mechanic that reflects

the topsy-turvy tone of the game.

Dynamics

Dynamics refers to the “behavior” of the game, the actual events and phenomena that

occur as the game is played. When viewing the game in terms of its dynamics, the

question asked is, “What happens when the game is played?” The relationship between

dynamics and mechanics is one of emergence. A game’s dynamics emerge from its

mechanics (LeBlanc 440-41). If the mechanics are a set of rules or a system of

constraints, then dynamics are how players operate within that system.

When playing Dishonored (2012), a first-person stealth action-adventure game

where the player undertakes the role of a scorned assassin Corvo, choosing to sneak past

a guard rather than execute him is an example of the game’s dynamics. A dynamic choice

need not be a decision between a better or worse action, though the outcomes they

produce may differ. If the player executes a guard, then his comrades might hear the

struggle and be alerted to Corvo’s presence. If the player fails to properly perform a

stealth move, which is more difficult than most execution mechanics, then they might

lose more health in the process. Choosing stealth over vicious is not a right or wrong

choice, but purely a matter of a gamer’s desired play style.

2

This is, after all, the same game that describes a quasar grenade as E=mc^(OMG)/wtf

10

Affects

In Hunicke, eBlanc, and Zubek’s initial proposal of MDA as a formal analysis of

gameplay, the A stood for “aesthetics.” I find the term “aesthetics” problematic as it is

more often used to describe artistic quality and not an experience. Instead, and in order to

maintain the MDA acronym, I have chosen to use the term “affect,” rather than aesthetic.

Affect, as defined in the field of cultural studies, is more than just a sensation, emotion,

and feeling. Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, in their seminal collection The Affect

Theory Reader, argue that affect “at its most anthropomorphic, is the name given to those

forces-visceral forces beneath, alongside or generally other than conscious knowing, vital

forces insisting beyond emotion-that can serve to drive us toward movement, toward

thought” (Seigworth 2). A video game’s affects are its emotional content, the desirable

emotional responses that players have that result from playing the game. A game’s affects

emerge from its dynamics (LeBlanc 441); how the game behaves determines how it

makes the player feel. For instance, the difference in affect between two racing games

from 1997, Mario Kart 64 and Diddy Kong Racing, is that the former intends to be fun

with its random item generator mechanics and its lack of dynamic options to compensate

for this apparent chaos. Diddy Kong Racing, on the other hand, has much more strategic

dynamic capabilities due to its hierarchical item generator system, thus creating a more

competitive affect.

Narrative

In Brian Upton’s Aesthetics of Play, in order to use game studies to critique and inform

literary studies, he starts his analysis “anchored firmly in much older critical and

11

philosophical traditions” (Upton 5). Like Upton, rather than “trying to protect game

studies from being colonized by literary studies” for this analysis I want to adapt

traditional narrative theories with medium-specificity in mind. Some of those differences

include video games non-linear, procedural, interactive, and ergodic nature (Ibid). This

isn’t a radical concept. Narrative scholar H. P. Abbott brought attention to the difference

between literary narratives and video games in aside for his primer, The Cambridge

Introduction to Narrative. For Abbott, the bare minimum definition of narrative is “the

representation of an event or a series of events” (Abbott 13). These events or sequence of

events constitute the text’s story and the narrative discourse is “how the story is conveyed

(Abbott 15). By this definition, story and narrative discourse share a similar emerging

relationship to mechanics and dynamics by Hunicke’s formulation. A game’s narrative

discourse is determined by how the rules at play (mechanics) are played (dynamics). But

a video game’s dynamics are not static. Per our Dishonored 2 example, a player may

experience a different narrative discourse based on their dynamic choices. How can this

multiplicity be resolved? This brings me back to the necessity to bear medium-specificity

in mind. For Abbott, Espen Aarseth’s Cybertext answers the “role-playing conundrum” in

a manner that is compatible and evolves somewhat seamlessly from traditional

definitions of narrative. For Aarseth, a sequence of events is not a story, but actions.

These actions or ergodic, “situation in which a chain of events… has been produced by

nontrivial efforts of one or more mechanisms (Aarseth Cybertext: Perspectives on

Ergodic Literature 113). These ergodic chains of events created by the player’s actions or

interactivity produce “intrigue,” events singular to each player based on their dynamics

choices:

12

[Rather] than a fixed story with its linear course, there are multiple possibilities,

and that particular series of events that actually happens is recorded in the manner

of a log: Instead of a narrative constituted of a story or plot, we get an intrigue-

oriented ergodic log (Aarseth Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature 113).

For our analysis, when discussing the events of the games installed by the developers

prior to the gamers playing, traditional literary terms (ex. story, plot, narrative) will be

used. Aarseth’s terminology will be used when discussing events of the games dependent

upon players’ interactions.

Methodology

As game designers, we need a way to analyze games, to try to understand them,

and to understand what works and what makes them interesting. We need a

critical language. And since this is basically a new form, despite its tremendous

growth and staggering diversity, we need to invent one (Costikyan 196).

In the sixteen years since Greg Costikyan laid down the theoretical gauntlet, numerous

designers and scholars have attempted to develop the Holy Grail of methodologies.

Similar to defining terms, this is no simple task nor is there a “correct” answer. Rather

than perform the tantamount task of creating an entirely new methodology, this analysis

will be using a refined version of the inquiry into drama in games set forth by Marc

LeBlanc in “Tools for Creating Dramatic Game Dynamics.” According to LeBlanc, the

topic of this essay “comes from [his] first lecture at the Game Developer’s Conference

(GDC) in 1999… At that time, it was becoming clear that our discourse on game design

needed more of a conceptual framework” (438). LeBlanc’s analysis is founded on three

13

questions: How does the narrative function create affect? What kinds of dynamics can

evoke the narrative? From what kinds of mechanics do those dynamics emerge? These

inquiries are “a way to place individual topics of discussion in their proper aesthetic

context” (Ibid). In this case, the individual topic of discussion is the gendering of female

FPSs and his three schemas for understanding games-mechanics, dynamics, and affects,

3

in terms of his three motivating questions form the basis for our conceptual framework,

ludonarrative synchronicity (LeBlanc 441).

Ludonarrative Synchronicity

Ludonarrative synchronicity is not just an adaptation to LeBlanc’s theories, but also a

response to a term that sparked a thousand Twitter posts: ludonarrative dissonance. The

term’s originator was Clint Hocking, a former level designer, game designer, and

scriptwriter for Ubisoft Montreal, who frequently blogged about his experiences as a

developer on his personal website, Click Nothing: Design From a Long Time Ago.

Hocking’s blog post “Ludonarrative Dissonance in BioShock” gave rise to a debate that

previously had been of little consequence, how narrative and gameplay are at odds in

video games. According to Espen Aarseth, editor-in-chief of Game Studies, this argument

is:

used as a touchstone by beginners to prove they know their way around the field,

but -- without exception, the writer doesn’t have a clue, and the paper is typically

about something entirely unrelated to the issue of whether games are narratives or

3

LeBLanc uses the term aesthetics as previously discussed in the terminology section.

14

not. What it does signal is that the writer feels the need to blend in, to show that

they are aware of some stuff that has gone before (in those murky days of 1998-

2001), but the effect is that they end up perpetuating the myth that there was a

group of narrative theorists who had a quarrel with another group called

‘ludologists’. (This is not the place to explain that great misunderstanding, instead

see Aarseth 2014, but suffice it to say that the so-called ludologists were all using

narratology, whereas the so-called narratologists were not, with the possible

exception of a little bit of Aristotle.) This is not at all to suggest that there should

be no more discussion of the relation between games and stories, because there is

very little actual, informed, productive disagreement in our field, both on that

topic and many others, and room for much more. Direct, vocal criticism is, or

should be, a sign of respect. So perhaps there is too little of both? (Aarseth "Game

Studies: How to Play -- Ten Play-Tips for Aspiring Game-Studies Scholar")

Hocking’s post was hardly informed or productive. He only uses the phrase

“ludonarrative dissonance” once, in the title, thus a firm definition of his term, or how he

defines ludology and/or narratology is never provided. It can be surmised that

ludonarrative dissonance refers to the gap between “what a text is about as a game and

what it is about as a story.” Despite the lack of scholarly context, after Hocking

published his blog post, the term was reused and repurposed by academics of various

disciplines and journalists alike. Computer scientist and physicists Mikael Hansson and

Stefan Karlsson in their study, “A Matter of Perspective: A Qualitative study of Player-

presence in First-person Video Games” used ludonarrative dissonance as “a perceived

disconnect by the player, brought on by inconsistencies between actions required of the

15

player, through a game’s ludology, and a narrative story portrayed within the fiction

context,” but they do not define what constitutes ludology (Hansson Mikael 2). Military

entertainment scholar Matthew Payne describes ludonarrative dissonance in War Bytes:

The Critique of Militainment in Spec Ops: The Line as a “disaffected state” (269).

Sociologist Scott Hughes ’ essay “Get real: Narrative and gameplay in ‘The Last of Us'”

uses the term ludonarrative dissonance in the abstract and is listed as a keyword, but like

Hocking he never actually uses it in his article. While Hocking’s term has become

common usage for players, developers, critics, journalists, and academics, not all agree

with its application. Semionaut and narrative designer Corvus Elrod regarded the term as

pointless and redundant. For example,

we have a situation where the fight choreography does not uphold the fiction

behind the show. But don’t refer to this as choreonarrative dissonance. Nor, for

that matter, do we refer to the poorly written and delivered dialog as

dialonarrative dissonance. Or the lackluster camera work as cinemanarrative

dissonance (Swain) .

From an industry-perspective Grantland’s resident video game journalist Tom Bissell

agrees that “some designers and critics regard ludonarrative dissonance as a core problem

in modern game design” (Bissell).Despite these objections, the term continues to be used

in game reviews, criticisms, and scholarly articles.

It is not my intention to continue in Hocking’s footsteps, but to co-opt this

popular usage of “ludonarrative”. Rather than assess whether a video game “manages to

successfully marry their ludic and narrative themes into a consistent and fully realized

whole,” ludonarrative synchronicity is designed to analyze how the ludic/gameplay and

16

narrative themes interact, whether in harmony or at odds, to create a subject (Hocking),

which in our case is gender. The how instead of what is part of the reason why

ludonarrative synchronicity is an effective methodology to analyze these female FPSs.

The problems surrounding female FPSs in this study is less a matter of what is included

in the games, but how these elements are gendered. The major obstacle to more female

FPSs developed is not just about inclusion, having more games feature a female lead, but

a matter of execution. This goes against a common argument for improved media

portrayals of non-white, cis-males, through increased visibility quantitatively. According

to filmmaker and trans-activist Jen Richards “there is a one word solution to almost all

the problems in trans media, we just need ‘more’. And that way, the occasional clumsy

representation, wouldn't matter as much because it wouldn’t be all that there is” (Feder).

The titles explored here, however, are less marred by clumsy or stereotypical

representations, but a lack thereof. Through comparative ludonarrative synchronicity,

pairing up two similar female FPSs with each other, we do not see a slew of problematic

portrayals of females, but hardly any recognition for their gender at all. When

ludonarrative synchronicity is lacking, when the narrative and gameplay do not interact

or gender two seemingly different subjects, then another (arguably greater) slight to

females occurs: the disappearance of their representation.

Insert Coin

In choosing which FPSs to focus on as sites of analyzing the gendering of games, I

implemented three criteria points. First, and foremost, I questioned whether the game

could be categorized as first person shooter via the use of the first-person camera and a

17

shooting mechanic. Second, I considered whether the female character was given or

chosen. I focused on characters that can be mechanized or in other words are movable

and actable. Three categories of character engagement emerged here: alternate choice,

customizable, and sole option. Last, but not least, I have considered the industry standing

of the games via their accreditation through AAA and their belonging to one of the four

periods of FPS game development.

Is the game a first-person shooter?

Mark J. P. Wolf argues that “player participation is arguably the central determinant in

describing and classifying video games, more so even than iconography” (113). For

instance, a game like Super Mario Bros. (1985), in which players direct Mario to jump

from platform to platform, beam to beam, cloud to cloud, is a “platformer.” A role-

playing game (RPGs) such as Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014), centers on the player

creating his character whether it is by the avatar’s appearance, skills, or social

interactions.

For a first-person shooter there are two aspects that separate these games from

other genres. The first is the game’s use of a first-person camera. Using the terminology

first-person “point of view” is a matter of contention, best explored by Alexander

Galloway in his essay “Origins of the First-Person Shooter.” This essay appeared in his

collection Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture which was meant to “formulate a few

conceptual movements, a few conceptual algorithms, for thinking about video games…

[but] above all, this book is about loving video games” (Galloway xii). In his “Origins of

the First-Person Shooter,” Alexander Galloway compares the subjective camera shot of

18

film noir to the first-person point of view camera in FPS. For Galloway, a subjective shot

is one of accuracy “when the camera shows what the actual eyes of a character would

see”, while a POV shot is a generalized approximation (41). This goes against visual

studies scholar Frederic Jameson who describes “‘Point of view’ in the strictest sense of

seeing through a character’s eyes” (112). Galloway clarifies his claim by noting that

“subjective shots are more extreme in their physiological mimicking of actual vision, for,

as stated, they pretend to peer outward from the eyes of an actual character rather than

simply to approximate a similar line of sight” (43). He explicates himself from this

argument of terms by saying that “video games are the first mass media to effectively

employ the first-person subjective perspective

4

… used to achieve an intuitive sense of

affective motion (Galloway 69). Rather than ask if modern-day FPS feature subjective or

POV shots, he emphasizes what these shots create: action? I emphasize modern-day as

the graphic capabilities of early FPS such as Doom and Wolfenstein wouldn’t allow for

loose, natural camera movements. Nowadays, with better technology, some FPS can

mimic the physiological state of a character, such as blurring one’s vision after being

injured or near death. As for why I choose to use the term “camera” rather than either

point of view or subjective view, “camera” emphasizes the player’s control over their

gaze. They are moving the camera, it is the player’s viewpoint, not their avatar’s.

The second integral aspect of FPS as a genre is the shooting mechanic.

Continuing with Galloway’s essay, weapons are as equally essential to the FPS as the

4

Underline added for emphasis

19

subjective perspective, with how an avatar’s weapon appears on screen (57). However,

Galloway does not see violence as a key for these types of games. FPSs are not the only

video game genre that feature violence. He argues that even a game like Metal Gear Solid

(1998) or Thief (2014) that feature weapons and killing, emphasize avoiding violence and

using a stealth dynamic instead (69). His argument, however, overlooks why players are

provided a weapon in the first place. A focus on stealth and pacifism doesn’t negate

violence as key to the FPS genre. For even if a player chooses (or tries) to avoid

committing carnage themselves, the enemies will retaliate nonetheless.

Is the female avatar given, not chosen?

According to Janet Murray, in her seminal piece Hamlet on the Holodeck, “an avatar is a

graphical figure like a character in a video game” (J. H. Murray 113). These can include

non-playable characters (NPCs) such as enemies, figures to populate the world, or side

characters who offer assistance. For our study, the focus is on the avatars that players can

control themselves. In FPSs, disembodied hands, wrist, and forearms typically are the

only portions of the playable avatar’s body presented on screen, along with a weapon in

the foreground. When it comes to avatars players can control, there are three types or

options: alternate choice, customizable, and sole option.

For a game like Left 4 Dead (2008), a FPS zombie-hunter, players have the choice

between four characters: Francis, an outlaw biker, Bill, a Vietnam Veteran, Zoey, a

university student, and Louis, a district account manager. In this particular title there is no

advantage or disadvantage between picking one avatar over the other, their stats are all

the same. Other titles, such as Dishonored 2 (2016) feature a choice between two

20

different avatars with a different set of abilities. One can play as Corvo, an experienced

assassin, or Emily, an assassin-in-training. Each has similar powers, but Corvo’s

mechanics are designed to favor melee-combat and Emily’s range abilities favor a more

cautious dynamic. It is less that there is an advantage or disadvantage, just a different

choice in playstyle.

Another type of avatar option is the customizable character. This is most often

found in RPGs where the player can change a number of aesthetic traits of their character.

The YouTube series Monster Factory highlights the degree to which players can alter

their avatar’s appearance. For Fallout 4 (2015), a post-apocalyptic RPG that allows

players to switch between first-person and third-person camera, the McElroy Brothers

created a monstrous being known as “Final Pam.” (Figure 2)

Figure #2: The Unyielding, The Undying, The Devourer, The Existence-

Eater, the Fearkeeper, Final Pam

21

Standing nearly ten feet tall, her face covered in pockmarks, with a sharply upturned nose

and chin, Final Pam the not-so-benevolent is an extreme example of what can happen

when players are given the opportunity to alter their avatar’s appearance. In fact, this

customization became so (in)famous amongst the gaming community that Bethesda,

Fallout’s publisher, made Final Pam canon with her inclusion in their online game,

Fallout 76 (2018). Not all customizations are purely for aesthetic purposes. While in

Destiny (2014), a multiplayer FPS, players first choose a race and gender that does not

affect access to any skills or change the game’s challenge level, when choosing their

avatar’s class and sub-class, these choices alter the mechanics and dynamics of the game.

A player could create a male Exo Titan Defender, given equipment and abilities

(mechanics) that favor melee combat (dynamic). Changing the Titan Defender to a

female Awoken race would not alter the given mechanics and resulting dynamics.

While not a FPS, Bioware’s Mass Effect (2007-2017) series had a unique

combination of a female character as both an alternate choice and a customizable avatar.

The default selection, John Shepard, can have his physical characteristics altered, along

with his background and class that changes his combat, technology, and magic skills. But

players were also given the option to turn Commander Shepard into “Fem-Shep.” While

the narrative that follows alters according to the customized character (in the first Mass

Effect, players were unable to romance NPCs of the same gender), male Commander

Shepard was the default choice with all of the advertising, promotional material, and

references being focused upon him. All of this despite the character model initially being

designed as female (Cooper).

For this project, I am concerned with the final type of avatar: the sole option,

22

where the player is given no choice in whom to pick as there is only one protagonist

whose qualities (ex. gender) cannot be customized or altered. Examples of this include

Lara Croft from Tomb Raider, Link from Legend of Zelda, or Master Chief from Halo.

There are no choices, one plays the single determined character the game provides as

given.

Was it produced by a “AAA” studio?

In the video game industry, AAA is equivalent to a major film studio like

Universal or book publisher such as Random House. Video game studios of this size

include BioWare, EA, and international powerhouse Nintendo. Mainstream titles are

usually regarded as being “at the cutting edge of game development… big budget

productions where only the speediest and most visceral graphical experiences will do”

(Dunning 93). I am restricting my search to AAA games as I contend that a female FPS

published by an indie studio will either lack the cultural impact of mainstream games or

not be creatively as hampered by the misogynist culture found in typical AAA studios.

To understand why the FPS genre has lagged behind in regard to gender equality,

the problem needs to be placed within the genre’s historical context. For the purpose of

this dissertation, I have broken down the chronology of FPSs into four historical periods:

the rise (1991-95), the dead zone (1996-2001), the peak (2002-09), and the collapse

(2010-18).

5

This chronology outlines the ways in which FPS games were initially seen as

5

Much of the history of FPS has been pulled from Klevjer’s “The Way of the Gun: The

aesthetic of the single-player First Person Shooter” and Hitchen’s “A Survey of First-

person Shooters and their Avatars.”

23

inclusive of both male and female players and subsequently shifted towards narrative and

aesthetic choices that privileged a masculine experience in opposition to a genre

designate for young female players.

The Rise (1991-95)

The FPS genre came about in the early 1990s thanks mainly to advancements in

computer graphics. Catacomb 3-D was the first wide-released FPS in 1991, though

stylistically more credit is given to Wolfenstein 3D (1992) as the birth of the genre (de

Meyer and Malliet).

6

During the rise of FPSs, the number of titles released rose

exponentially each year, from just one in 1991 to thirty-five in 1995. This initial stage

was conceived as inclusive of both male and female players. Other key titles released

during this period include System Shock (1994) and Star Wars: Dark Forces (1995). It

was also during this period where we can see a step away from “women games.” As

defined by Shira Chess in Ready Player Two, women games “are not games that women

play, but rather games that in their design, marketing, or style appear to be intended for

late teen or adult female audiences” (Chess 16). Chess points to the release of new

consoles (Sega Genesis in 1989, Super Nintendo Entertainment System in 1991, and the

PlayStation in 1995) as part of the turn from what was originally an inclusive market

(Chess 9). More violent titles, such as the FPSs Doom and Quake, were produced and

6

Some have argued that 1973’s Maze deserves the title of first first-person shooter, but

the game was never commercially released, rather it was freeware available via the

ARPANET. For more information refer to Richard Moss’ “The First First-Person

Shooter” from Polygon.

24

marketed specifically towards men (Kent 531). FPS games emerged in opposition to

“women games” and were seen as relevant to a predominant masculine audience.

The Dead Zone (1996-2001)

This period of growth was followed by a quick drop in ’96 where only twenty-two

titles were released. This lull continued into the 21st century, with an average of twenty-

two FPSs released a year. All of this decline was shaped despite and because of the

prevalence of new home console systems, including the original Playstation released in

1995 and the Nintendo 64 in 1996. Known as the fifth-console, 32-bit, or 64-bit era, these

systems had the capability to display FPSs, but could not compete with the quality of PCs

with their graphics and processing speeds. However, the arcades that were the secondary

market for these FPSs were in decline because of the 5th-generation consoles. It was a

time of technological transition and the FPS genre got caught in the middle. Still, several

classic games and franchises rose from that dead zone, including Quake (1996), Dark

Forces II (1997), and Unreal (1998). It was also during this time that the gap between

male and female games grew as “in the mid-to-late 1990s there began a slower

emergency of video games specifically targeting young girls” (Chess 10). These games

often featured pop culture figures, such as Barbie, and simplified, feminized gameplay

involving the likes of dress-up or interior design. Despite this lull in both FPSs and

action-based female games, 2000 saw the first two female-led FPSs released: Perfect

Dark and The Operative: No One Lives Forever. This would become a trend for female

FPSs, that when the market was in despair, developers took chances of female leads.

25

The Peak (2002-09)

Just as suddenly as the FPS genre lost popularity, it shot back up, raising from

twenty-three titles in 2001 to thirty-eight in 2002. Metroid Prime was among the games

released during this time period. The highpoint of this era was in 2005, when fifty-five

FPSs were made available. In 2006, Gamasutra reported the first-person shooter as one

of the biggest and fastest growing video game genres in terms of revenue for publishers

(Cifaldi). Much of this increase was due to the arrival of the seventh-generation consoles

such as the XBOX 360 in 2005 and the PlayStation 3 in 2006. There was a small dip or

valley between ’06 to ’08, but the average number of titles released still averaged forty-

three games a year. During this gully, the first Portal (2007) and Mirror’s Edge (2008)

titles were released, just as we saw with Perfect Dark and The Operative.

The Collapse (2010-2018)

After a quick bump back up into the 50s in 2009, the FPS genre collapsed. From

2010 to 2018 the average number of FPSs released was eighteen titles, with a high of

thirty-two in 2011 and a low of ten in 2018. The period included only a single female

FPSs produced, Alien Isolation. However, if the trend established continues, this low

period could signal the production of more female FPSs title in the near future. Female

oriented FPS games tend to emerge in moments of crisis and decline of traditionally

masculine-coded games within the genre.

This dissertation analyzes several FPS with female protagonists to explore how

the games gender (or not) their female texts. It does so by considering the gendering of

games as a phenomenon articulated within the ebbs and flows of the gaming industry

26

broadly defined. I have selected six games representative of three periods of development

within the AAA cluster: Perfect Dark and The Operative: No One Lives Forever as

representing The Dead Zone Period; Metroid Prime, Portal, and Mirror’s Edge as

exemplary of The Peak, and Alien: Isolation as prototypical of The Collapse stage.

Below are six games that fit my criteria and are thus analyzed in terms of their gendering

in this dissertation:

Title

(Initial) Year of

Release*

Developer

Historical

State

Perfect Dark 2000 Rare Dead Zone

The Operative: No One

Lives Forever

2000

Monolith

Productions

Dead Zone

Metroid Prime 2002

Nintendo/Retro

Games

Peak

Portal 2007 Valve Corporation Peak

Mirror’s Edge 2008 E.A./Dice Peak

Alien: Isolation 2014

Creative

Assembly/Sega

Collapse

All these texts, sans Alien: Isolation, have sequels or reboots, hence the use of

“(initial) year of release.” Unless there was a change in developer or massive change in

the production team, I will be analyzing not just the original game but its follow-ups as

well.

Literature Review

The conceptual approach of this chapter is how FPS establish gender through

both gameplay and narrative. As such it is key to understand how feminist/gender and

27

visual studies are interpreted through video game studies. Concepts of particular interest

are the bodies and genders of avatars, how the “camera” is controlled in FPSs, and what

is seen through this “lens.”

Female or Feminine?

One of Judith Butler’s most famous maxims may be that “gender is in no way a

stable identity… rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time” (Butler

"Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist

Theory" 519). Butler is not avoiding defining gender, she is trying to turn away from the

binary categories of man and woman and the ever-changing qualities associated with

femininity and masculinity. Continuing this temporal explanation, Butler quotes de

Beauvoir who “claims that woman is an ‘historical situation,’ she emphasizes that the

body suffers a certain cultural construction” (Butler "Performative Acts and Gender

Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory" 523). These claims

stand in stark contrast to other feminist scholars like Susan Bordo and Moira Gatens. For

them, the body is not an abstraction constantly undergoing the process of identity

formation by means of various performances. The body is material (Thomas 58, 62).

Both Bordo and Gatens rebel against the idea of how the body is “tabula rasa, awaiting

inscription by culture” (Bordo 35). Gatens takes aim at how the gender feminism of de

Beauvoir “took the female and the male body to be passive and inert, a blank sheet ready

to be written on through the processes of socialization and in so doing, maintained the

mind/body opposition which is the cornerstone of western thought” (Thomas 57). What

these inscriptions miss is the processes of nature. Bordo brings in this factor to female

28

development, building upon rather than discarding Butler and other Foucauldian gender

feminist, focusing on how the embodied experience is affected by culture, history, and

biology (Bordo 34, 42). For Bordo, despite what qualities a body takes on or performs,

one cannot escape their body and the biological facets that come with it. Don Ihde, in

Bodies in Technology, finds a way to combine both Bordo and Butler’s perspectives. He

uses “body two” in his work to define the “culturally constructed body that echoes with a

Foucauldian framework, the cultural body as experienced body” (Ihde 17). “Body one,”

on the other hand refers “to the bodily experience that Merleau-Ponty elicits…

perspective as a form of phenomenological materialism insofar as his concept of the lived

body is one that holds that the active, perceptual being of incarnate embodiment” (Ihde

16-17).

7

But what about virtual bodies, without any materiality to be had? Could these be

a “body three?”

Cyborgs

As mentioned in the “Tutorial” section “an avatar [as] a graphical figure like a

character in a video game,” but also according to Janet Murray avatars are a “mask that

creates the boundary of the immersive reality and signals that we are role-playing rather

than acting as ourselves” (113). Returning to our previous discussion, Judith Butler

argues that “gender is instituted through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be

understood as the mundane way in which body gestures, movements, and enactments of

7

We will discuss embodiment in greater detail later in Level Three, particularly

regarding the game Portal.

29

various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self” (Butler "Performative

Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory" 519).

Avatars in video games are a kind of bodily enactment that can fulfill Simone de

Beauvoir’s claim that “one is not born, but rather, becomes a woman,” through the

player’s performance of the avatar’s, rather than their own, identity. Donna Haraway

echoes this language, referring to cyborgs as uncanny creatures that are not born, but

constructed, entities epitomizing “transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous

possibilities” (Haraway 154).

This aspect of being unborn is what differs females of the material world from

their cyborg counterparts. The biological function of birthing is missing. In Fallout 3

(2008) the game begins

for the player who initially sees nothing but a black screen. Gradually, some

bright light appears, we hear a heart monitor, and (what we assume is a doctor’s

face materializes out of the dark. It becomes apparent that the player is

experiencing his/her own birth: the onscreen darkness represents the dark of the

birth canal; the bright lights are those of the operating room; the first voice you

hear is that of the doctor, who, it turns out, is your own father. Your father asks

you to choose your gender, your name, and then he employs a “gene projector” to

“see what you’ll look like when you’re all grown up.” (Boulter 18-19)

Jonathan Boulter, author of Parables of the Posthuman: Digital Realities, Gaming, and

the Player Experience, deems this sequence as “the birth of the player,” not the avatar.

The absence of the mother in this instance is not an anomaly, but a seedy trope within

video games. From BioShock to Dishonored, Far Cry 4 to Mirror’s Edge, “the most

30

common state for a mother in games, is to be dead. Deaths often occur in childbirth or the

early childhoods of protagonists (Campbell). Susan Bordo, in her analysis of reproductive

rights and the politics of subject-ivity, asks are mothers (the epitome of female biology)

persons (Bordo 71)? Apparently not in video games. This is just another example of how

video games fail to recognize gender. For scholars like Haraway, cyborgs offer liberation,

they are “a matter of fiction and lived experience and that changes what counts as

women’s experience” (Haraway 149). Cyborgs are “creatures of a ‘post-gender world… a

world without gender which is also a world without genesis” (Haraway 150). It is,

however, without biological beginnings that video game avatars enter a world not where

the male/female binary has been overcome but erased. Females have been made invisible.

Upon return to definitions of gendering as formed by Butler and de Beauvoir, then

an avatar can become female. Scholars like Boulter focus on the relationship between

players and their avatar’s identity created by that player and their experiences. I,

however, wish to focus on the formation of an avatar’s identity prior to a player’s ergodic

actions. With the exception of Fallout 3, a majority of FPSs’ stories start with avatars in

media res, already experiencing the game’s overall narrative. The avatar given to the

player is one who has already been performing and thus undergoing the gender process.

Future post-human scholars could add a fourth sub-question to the purpose of this

ludonarrative synchronic analysis. Rather than just “does the narrative and gameplay

reference the same gender,” they could ask “does the game start (with the pre-defined

narrative) and end (through the player’s intrigue-oriented ergodic log”) with the same

gender?

31

Plurality of Identities

Bear in mind that not all females, material or otherwise, are alike. This is one the core

tenet of intersectionalism. For this dissertation, I am deploying Patricia Collins and Sirma

Bilge’s definition of intersectionality.

Intersectionality is a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the

world, in people, and in human experiences. The events and conditions of social

and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor.

They are generally shaped by many factors in diverse and mutually influencing

ways… Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the

complexity of the world and of themselves (Collins and Bilge 2)

Collins and Bilge’s interpretation of intersectionalism is heavily influenced by Kimberle

Crenshaw’s work, particularly “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics,

and Violence Against Women of Color.” In this piece, Crenshaw considers

intersectionality a provisional concept linking contemporary politics with

postmodern theory. In mapping the intersections of race and gender, the concept

does engage dominant assumptions that race and gender are essentially separate

categories. By tracing the categories to their intersections, I hope to suggest a

methodology that will ultimately disrupt the tendencies to see race and gender as

exclusive or separable (1244)

As for the many factors alluded to by Collins and Bilge, Crenshaw writes that “the

concept [intersectionalism] can and should be expanded by factoring in issues such as

class, sexual orientation, age and color” (1245).

32

Since the mid-to-late 90s game studies, particularly feminist game studies, have used

“intersectional approaches to consider larger issues of diversity such as sexuality,

ethnicity, social class, and other factors [that] play into and exacerbate problems that

have already been documented in terms of gender within video games” and the industry

(Chess 16,19). In Video Games Have Always Been Queer, Bonnie Ruberg pushes for

other forms of intersectional engagement including disability, neurodiversity, religion,

and nationality; several of which are touched upon in this dissertation (13).

Straight to Video (Games)

Books about new media often make a point of emphasizing how video games

represent a radical break from older forms of art… the purpose behind putting

forth this idea of a radical breaks seems to be two-fold: to carve out a unique

critical space for discussing games that frees the discourse from the constraints of

pre-existing critical methodologies and to establish video games as being on the

vanguard of some sort of postmodern cultural revolution. I disagree with his

approach (Upton 5).

While it is important to recognize the medium specifics of video games, it is just as

imperative to recognize the landscape set by previous art forms and their engagement

with one another. Numerous game studies scholars have backgrounds in film studies such

as Bernard Perron and Mark J.P. Wolf, as well as multiple creatives who work in both

genres like Ken Levine (BioShock) and Rhianna Pratchett (Mirror’s Edge, Tomb Raider).

Beyond personnel, there are a myriad of overlaps between the two entertainment formats.

To grab as large of a market share as possible, as early as “the 1980s video games such as

33

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (Atari, 1982), capitalised on the fame of their cinematic

counterparts to attract new audiences” (Fassone, Giordano and Girina). This trend

continues today with the release of film-based games such as Days of Thunder (2011) and

Mad Max (2015), but also vice-versa, with Hollywood producing films-based-on-games,

like Pokémon: Detective Pikachu (2019) and Sonic the Hedgehog (2020). Video game

series such as Kingdom Hearts, which brings together characters from the Final Fantasy

video game franchise with the Wonderful World of Disney, exemplify the boundless

nature found in modern trans-media cooperation. “The relationship and reciprocal

influence between cinema and video games goes well beyond storylines and characters”

to technical techniques as well (Fassone, Giordano and Girina). Our focal point here is

the use of the camera and the difference between what is seen by its lens in film versus

video games.

Gamer’s Gaze

The spectator identifies with himself, with himself as a pure act of perception (as

wakefulness, alertness): as the condition of possibility of the perceived and hence

as a kind of transcendental subject, which comes before every there is… and it is

true that as he identifies with himself as look, the spectator can do no other than

identify with the camera, too” (Metz 25)

A viewer can relate to the cinematic camera, and often the subjects on screen, but they do

not control this camera. What makes the camera’s viewpoint in video games different

than those used in film is that the gamer can control the field of view to a greater extent.

While developers can control and place restrictions on just how far the gamer can turn the

34

camera, usually keeping it anchored as so the gamer never loses sight of their avatar, the

gamer still has choices that are missing from the film viewer’s experience. The gamer’s

gaze isn’t fixed. Film controls the dimension of time and space and such coding allows

the camera and filmmakers to create the gaze. Therefore, in comparison to moviegoers,

gamers’ have greater freedom to create their own spectacle through their experience with

their avatar.

Point of View

There are two camera views that are most often used in video games to display

the world inhabited by the avatar: third-person and first-person. Video games presented

in the third-person lack the camera placement and freedom of movement like its

omniscient cinematic brethren. In films, the camera’s location is often only restricted by

the 180-degree rule. Outside of this, it can focus on any key subject it wishes from a

manner of perspectives. The third-person camera in a video game is almost always locked

on to the avatar, restricted to following the player’s character.

Back to the debate surrounding Alexander Galloway’s definition of POVs shot as

a form of generalized approximation (41) while “subjective shots [are] more extreme in

their physiological mimicking of actual vision, for, as stated, they pretend to peer

outward from the eyes of an actual character rather than simply to approximate a similar

line of sight” (43). Which raises the question, do modern-day FPS feature subjective or

POV shots? I emphasize modern-day as the graphic capabilities of early FPS such as

Doom and Wolfenstein wouldn’t allow for loose, natural camera movements. Nowadays,

with better technology, some FPS can mimic the physiological state of a character, such

35

as blurring one’s vision after being injured or near death. Nicholas Mirzoeff tells us of

soldiers describing their actions “as being like a videogame” are not speaking in the

metaphorical sense” (297). This, however, is not the case in all FPS and will be a point of

contention discussed in relation to each game.

The female point of view is nigh absent in video games. Approximately only 25%

of all genres of video games have a playable female leads. Amongst this sample, a

majority of these games use the third-person, rather than the first-person, camera view

(Hitchens). This includes iconic female characters such as Lara Croft, Bayonetta, and

Ellie from The Last of Us series. However, the inclusion of female characters does not

inherently create the female point of view.

The power of Classical Hollywood cinema regarding how it portrays women, is in

how it “builds the way she is to be looked at into the spectacle itself” (Mulvey 716). This

is achieved by

forming a scopophilic instinct (pleasure in looking at another person as an erotic

object), and, in contradistinction, ego libido (forming identification processes) act

as formations mechanics [so that] the image of woman as (passive) raw material

for the (active) gaze of man adds a further layer demanded by the ideologically of

the patriarchal order as it is worked out in its favorite cinematic form—

illusionistic narrative film (Mulvey 724).

Including a female avatar as playable, and thus active, adds a layer of complication to this

argument. However, by relying on classic Hollywood cinematic techniques, video games

risk the inherent heteronormativity of the woman as image and man as bearer of the look

(Mulvey 719). Thus, to avoid the failings of Western filmmaking, video games can turn

36

to avante-garde cinematography Mulvey recommended and practiced herself. Examples

of such include Riddles of the Sphinx (1977), which begins with Mulvey directly

addressing the camera/viewer. While breaking the fourth wall in cinema is often used

“destroy the satisfaction, pleasure and privilege of the “invisible guest” or camera, it is

only natural for NPCs to address the camera/viewer in first-person shooters (Mulvey 725-

26).

Chapter Preview

One way to think about the organization of this dissertation is chronologically as

with the exception of Alien: Isolation, the case studies are presented in chronological

order, based on their release dates. This allows us to explore how female FPSs have

evolved alongside the video game genre itself and view the titles in context with other

FPSs of each period. Another way to consider the layout of this project is thematically,

since it follows not only the evolution of the female FPS, but each text is paired with

other titles that feature similar issues of gendering games, from gameplay that deprives

females from specific actions all the way to narratives that confront feminists issues head

on.

Level One: Svelte Spies

Perfect Dark and The Operative: No One Lives Forever were the first two games

released with a solely playable female avatar in the FPS genre. Not only were the games

released the same year, but they feature similar leads (international spy) and influences

(James Bond). Their comparison highlights the objectification and consumerism of the

37

female body, set forth by scholars such as Baudrillard and Bordo. The aesthetics of the

protagonists have obvious narrative implications, but it is how the games integrate their

clothed bodies into the gameplay that emphasizes the gendering of the texts.

Level Two: Alien Queen(s)

Space-based FPSs have explored infinity and beyond since the original Doom sent

Doomguy to the moons of Mars to fight demons and the undead. It is this focus on

exploration that separates our two space sirens, Samus from Metroid Prime and Amanda

Ripley of Alien: Isolation from other inter-galactic titles based purely on combat. While

both games feature numerous battles, the games emphasize exploration and discovery as

a way to improve one’s chances when fighting carnivorous creatures. Could it be that the

gameplay emphasizes a brain over brawn dynamic based on female stereotypes

surrounding physicality and mental capacity Stereotypes are just one form of

predetermined expectations that affect Samus and Amanda. Unlike the other games in

this study, Metroid Prime and Alien: Isolation’s protagonist are not original characters.

Both characters are part of popular multimedia franchises and players press start with

numerous presumptions already in place. Due to their in-media res nature, the gendering

of these games appears locked in from the start, but is the choice to have female fighters

as necessary as it first appears?

Level Three: Bullet (Free)-Time

Portal and Mirror’s Edge complicate the FPS genre by introducing two additional

intersectional elements to the gendering of games, namely race and pacifism. Chell and

38

Faith of Portal and Mirror’s Edge respectively allow for an intersectional study of female

FPSs as neither are the default white, male nor fit the mold of previous female leads.

These titles also present an alternative, less-violent approach to shooters. This raises the

question of whether Portal or Mirror’s Edge feature divergent gameplay because of their

unconventional protagonists or does their hero’s gender play little to no role in their

title’s more pacified play-style?

Boss Battle

Represented violence can take many forms. Where Judith Halberstm

8

uses literary

and cinematic examples to explore imagined/queer violence, I use video games. Like

Judith Halberstram’s seminal piece, “Imagined Violence/Queer Violence,” I’m

implementing fictional examples of imagined violence and articulated rage via video

games “to elaborate a theory of the production of counter realities as a powerful strategy

of revolt emanating from an increasingly queer postmodern political culture”

(Halberstram 190). This chapter features the culmination of trends found through my six

case studies, particularly how females enact violence. I discuss what females shoot with,

who they shoot, and how often they actually don’t use weapons. Finally, a delve into the

current landscape looks like and what the future of female FPSs could be.

8

I’ve chosen to refer to Halberstram as Judith when discussing pieces they initially

published under that name and Jack when discussing their current work.

39

Level One: Spy vs. Spy

It wasn’t until the year 2000 for a mainstream first-person shooter to come out featuring a

female, and only a female lead. Perfect Dark’s Joanna Drake and The Operative’s Cate

Archer. Rare’s Perfect Dark and Monolith Productions The Operative: No One Lives

Forever were released within six months of each other, on separate consoles (Perfect

Dark on the N64, The Operative for PS2). Unlike their male counterparts of the time,

such as Deus Ex’s JC Denton or the nameless soldiers in Counter Strike, Drake and

Archer had personality and a flair for fashion. Comparing Perfect Dark and The

Operative: No One Lives Forever highlights the objectification and consumerism of the

female body, as set forth by scholars such as Baudrillard and Bordo. The physical