Maya Ethnogenesis

By

Matthew Restall

pennsylvania state university

resumen

Eran los mayas de Yucatán verdaderamente mayas? Con respeto a las identitades a las

cuales pretendían y las que otros les daban, los mayas no eran mayas.Este artículo exam-

ina fuentes coloniales que demuestran que los habitantes indígenas de la península no

se llamaban a si mismos “maya” ni utilizaban ningún otro término étnico para identifi-

carse como parte de un grupo étnico común. Este artículo explora el género de identi-

tad maya durante los siglos coloniales, utilizando principalmente fuentes en lengua

maya yucateca. El artículo analiza tres circunstancias que afectaron ésta “etnogénesis

maya”—los conceptos de raza impuestos por los españoles durante la colonia, la Guerra

de Castas en el siglo XIX, y la etnopolítica del siglo XX, enfatizando el efecto gradual,

sutil o indirecto de cada uno de éstos contextos.

palabras claves: Identidad, Cultura, Etnogénsis, Mayas, Yucatán. keywords:

Identity, Culture, Ethnogenesis, Mayas, Yucatan.

Inventing Mayas

Were the Mayas of colonial Yucatan actually Mayas? In terms of both the

identities they claimed and those assigned to them, they were not. Colonial-era evi-

dence shows that the native inhabitants of the peninsula, whom modern scholars

identify as “Maya,” did not consistently call themselves that or any other name that

indicated they saw themselves as members of a common ethnic group. Nor did

Spaniards or Africans in colonial Yucatan refer to the Mayas as “Mayas.”

Nevertheless, the term “Maya” was in use in Yucatan in colonial times and most

likely in the post-classic period too (if it is rooted, as I argue below, in the toponym

“Mayapan”). Today it is the conventional term used in all languages to refer to a

broad swathe of peoples in the so-called “Maya area” of southern Mesoamerica. The

term has acquired considerable baggage, much of it contested, though arguably

insufficiently so. In Edward Fischer’s words, “Maya scholars and peasants alike con-

64 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

The Journal of Latin American Anthropology 9(1):64–89, copyright © 2004, American Anthropological Association

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 64

tinue to assert the legitimacy of an essentialist cultural paradigm, arguing that there

is a metaphysical quality to Maya-ness that transcends the minutia of opportunistic

construction” (2001: 243). Fischer is willing neither to embrace nor dismiss views of

“Maya identity as nothing more than the product of counterhegemonic resistance or

the romantic musings of anthropologists” (2001: 243); his compromise is “to view

Maya culture as an historically continuous construction that adapts to changing cir-

cumstances while remaining true to a perceived essence of Maya-ness” (2001: 246;

also see 15–19). Quetzil Castañeda’s position is somewhat less compromising; for

him,“categories of Maya, Maya culture, and Maya civilization are not at all empty of

meaning or reality, but ...are fundamentally contested terms that have no essential

entity outside of the complex histories of sociopolitical struggles” (1996: 13).

The presupposition of this article is that the issues surrounding “Maya” as a

“contested term” are relevant to the colonial period, and vice versa; the article’s pur-

pose is to approach this debate from the perspective of the colonial period, and to

contribute to it by demonstrating how colonial-period evidence disproves the com-

monly made assumption that in previous centuries Mayas shared a sense of com-

mon ethnic identity. In the introduction to The Invention of Ethnicity, We rn er

Sollors refers to Ernest Gellner’s argument that “nationalism is not the awakening

of nations to self-consciousness; it invents nations where they do not exist” (1989:

xi); my position is that modern Maya ethnogenesis had to invent Maya ethnic iden-

tity because there was no Maya ethnic self-consciousness in pre-modern times to

which Mayas could awake.

Because of its modern ubiquity, I begin with the term “Maya,” examining its

meaning to Mayas of the Conquest and colonial periods in Yucatan, using Yucatec

Maya-language sources to categorize its usage. I then briefly further explore the

nature of Maya identity during these centuries, likewise using archival evidence pri-

marily in Yucatec Maya, to search for possible alternative terms or bases of ethnic

identity. Finding no clear ethnic component to self-ascribed colonial Maya identi-

ties, but at the same time uncovering hints of ethnic awareness in the written record,

I resort to breaking down the broad category of “ethnic identity” into two sub-cat-

egories, overt ethnicity and implied ethnicity (both explained further below).

Finally, I look very briefly at three circumstances that impacted “Maya ethnogene-

sis”—colonial Spanish ethnoracial concepts; the Caste War; and twentieth-century

ethnopolitics—emphasizing the muted, gradual, or indirect nature of their impact.

“Maya” in the Colonial Period

If the historical roots of Maya ethnic identity are an illusion, what of the colonial-

era use of the term “Maya”? It does not appear at all in Spanish-language written

Maya Ethnogenesis 65

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 65

66 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

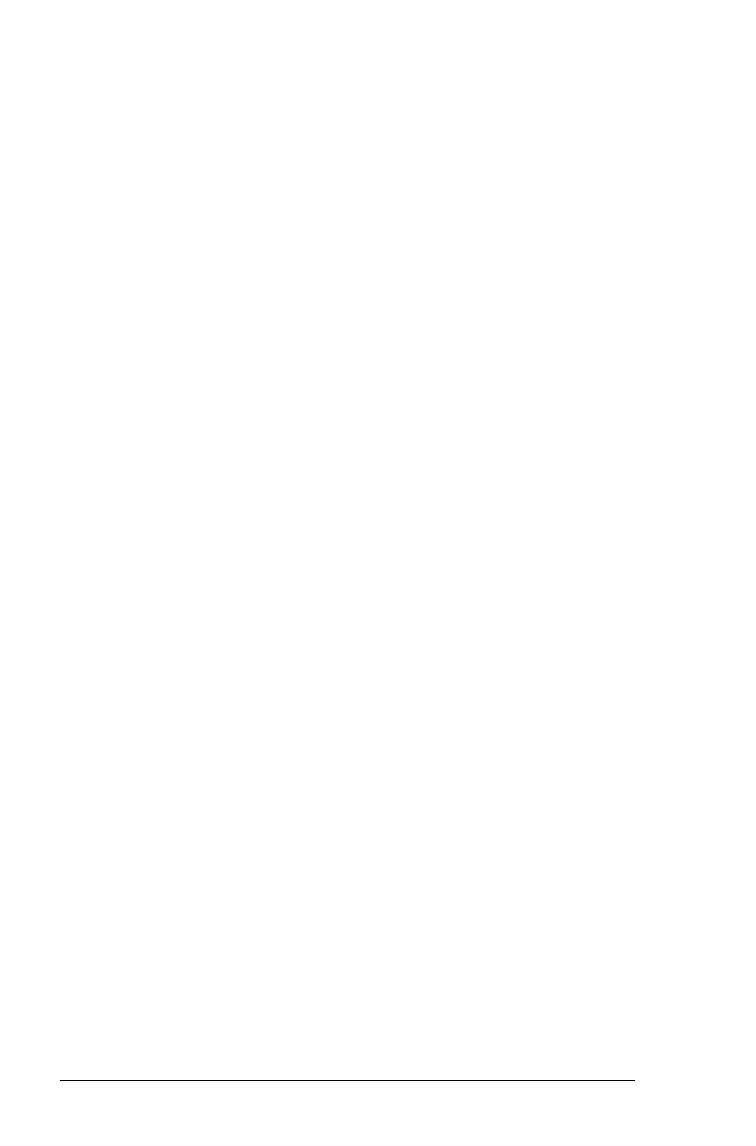

table 1

Uses of the term “Maya” in colonial Maya-language sources

phrase reference type date source: genre, town

(region) (incidence)

maya tan cultural: colonial quasi-notarial & notarial

“the Maya language” sources (numerous)*

maya cuzamil toponym (Cozumel) colonial Book of Chilam Balam, Chumayel

(Xiu) (thrice)

mayapan toponym (Mayapan) colonial quasi-notarial & notarial sources

(numerous)

uchben maya xoc cultural/material: colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

“the ancient Maya count” Tizimin (east) (once)

maya pom cultural/material: 1669 cabildo petition, Calkiní

“Maya copal incense” (Calkiní) (once)

maya ciie cultural/material: colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

“Maya wine” Chumayel (Xiu) (once)

maya zuhuye cultural/material: colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

“Maya Virgin” Chumayel (Xiu) (once)

maya ah ytzae to others: colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

“those Itza Mayas” Chumayel (Xiu) (once)

maya ah kinob to others: colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

“Maya priests” Chumayel (Xiu) (once)

maya uinicob(i) to others: “(the) colonial Book of Chilam Balam,

Maya men/people” Chumayel (Xiu) (eight times);

Titles of the Pech, Chicxulub and

Yaxkukul (Pech) (twice)

maya uinicob to others: to colonial Titles of the Pech,

commoners by nobles (1769) Chicxulub and Yaxkukul (Pech)

(once)

maya uinicob to others: of colonial Titles of the Pech,

another Yucatec region (1769) Chicxulub and Yaxkukul (Pech)

(once)

maya uinicob to others: to Yucatec 1567/1612 Title of Acalan-Tixchel

Mayas by Chontal Mayas (Chontal region) (once)

coon maya uinice self-reference: “we 1662 individual petition,

Maya men/people” Yaxakumche (Xiu) (once)

coon maya uinice self-reference 1669 cabildo petition, Baca (Pech)

(once)**

con maya uinice self-reference colonial Book of Chilam Balam, Chumayel

(Xiu) (once)

coon ah maya uinice self-reference (as nobles colonial Title of Calkiní (Calkiní)

of the Canul chibal)(1595/1821)(once)

Sources: Edmonson (1982: 169); AGI (Escribanía 317b, 9: folio 9); Roys (1933: 28); TLH (The Title of

Calkiní: folio 36); Roys (1933: 57); Roys (1933: 47, 58, 59); Roys (1933: 61); Roys (1933: 58); Roys (1933: 53,

55, 56, 31, 27, 24, 56); TLH and TULAL (Title of Chicxulub: folios 6, 8, 15) and (Title of Yaxkukul: folios 3v,

4r, 8v); AGI (México 138, the Title of Acalan-Tixchel: folio 76r); TLH (Xiu Chronicle:#35); AGI

(Escribanía 317a, 2: folio 147); Roys (1933: 20). For many of these examples, also see Restall (1997: 13–15;

1998: 35, 44, 74, 101, 116, 121, 124, 127, 134, 177, 233).

*A notarial example is in AGN (Bienes Nacionales 5, 35: folio 5); a quasi-notarial one is in Roys (1933: 40).

**This is an example; the phrase appears several other times in near-identical petitions from other

north-west cahob in 1668–69 (AGI, Escribanía 317a, 2: various folios).

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 66

sources, as Spaniards preferred the generic indio. The term does appear in Maya-

language sources, but with little consistency or frequency. Table 1 lists examples of

this usage, with types of usage categorized and listed according to frequency of

attestation.

The primary category is one I have labeled “cultural,” containing references to

the Yucatec language, as the term was mostly used as an adjective to describe it

(maya t

an, “Maya speech or language”); Landa’s only reference to the term’s ety-

mology is to “the language of the land being known as Maya” (la lengua de la tierra

llaman maya; Landa 1959: 13; Restall and Chuchiak, n.d.). The persistence of this

connotation as primary to the term among the Maya themselves is illustrated suc-

cinctly in the dictionary of present-day Yucatec by Victoria Bricker and her native

collaborators; the sole entry under “Maya” is “maya

ʔ

-t’àan, Maya language” (maya

t

an in colonial orthography; Bricker et al 1998: 181).

1

The context of Landa’s comment is the second category of usage, labeled

“toponym” in Table 1; the Franciscan asserts that the place-name “Mayapan” was

derived from the term “Maya.” However, no other toponym in Yucatan contains the

element “Maya”; when, in a single quasi-notarial source, the term is attached to the

name for Cozumel island, the context is a sacred association to Mayapan (Edmon-

son 1986: 47, 58, 59). Indeed, I suspect that the reverse of Landa’s suggestion is true,

that “Maya” derived from “Mayapan.” This hypothesis is consistent with: first, the

term’s association with, and primary usage in, the northwest, where Mayapan is

located; second, the entry in the 16th Century dictionary from Motul, also in the

northwest,that glosses maya as nombre proprio desta tierra (Ciudad Real n.d., 1: folio

287v; Arzápalo Marín 1995, 1: 489); third, the term’s vague link to the Itzas, who, like

Mayapan, were seen as part of the semi-sacred, semi-mythic historical past of the

peninsula; and fourth, the following passage from the Chilam Balam of Chumayel

(translation mine, but see Roys 1933: 50, 140; Edmonson 1986: 59):

oxlahun ahau u katunil u 13 Ahau was the katun when they

he›cob cah mayapan: maya founded the cah of Mayapan; they

uinic u kabaob: uaxac ahau were [thus] called Maya men. In 8

paxci u cabobi: ca uecchahi Ahau their lands were destroyed

ti peten tulacal: uac katuni and they were scattered through-

paxciob ca haui u maya out the peninsula. Six katun after

kabaob: bulub ahau u kaba they were destroyed they ceased

u katunil hauci u maya to be called Maya; 11 Ahau was

kabaob maya uinicob: the name of the katun when the

christiano u kabaob Maya men ceased to be called Maya

[and] were called Christians.

Maya Ethnogenesis 67

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 67

These annals entries offer both an explanation of the diffusion of the term

“Maya”—a product of the Diaspora created by the fall and abandonment of Maya-

pan—and a clear association of the term with the pre-Conquest pagan past. This

hypothesis on the origins of the term was also circulating in 16th Century Yucatan;

a dozen years after Landa claimed that the derivation was the reverse, an old con-

quistador of the province, the encomendero for the cah (Maya community) of Dzan,

wrote in the Relaciones Geográficas that “this province speaks but one language,

called Maya, its name derived from Mayapan” (RHGY, 1: 156).

2

Of course, accepting that “Maya” comes from “Mayapan” begs the question as

to the toponym’s etymology. If “Mayapan” did indeed precede “Maya,” then Landa’s

explanation of the toponym el pendón de la Maya, (the banner of the Maya) would

only have meaning after the site became a major city (Landa 1959: 13; Restall and

Chuchiak n.d.). However, there are many possible alternative roots. May and Pan

are both Maya patronyms, for example; pan also means “dig, sink (a well), plant (a

tree)” and ah pan thus “he who digs,” with May Ah Pan,“(the land of) May, the well

digger.” As yapan means “broken up,” the origin could be a reference to the stony

ground, with ma yapan, “not broken up, unbroken (terrain).”

The tertiary category of usages of “Maya,” labeled “cultural/material” in Table 1,

consists of references to material objects native to the peninsula (such as maya pom,

“Maya copal incense”) or to local cultural practices (such as uchben maya xoc, “the

ancient Maya count”). The significance of these types of references is that not only

are they rare, but they all have sacred connotations and are consistent with the

toponymic use of the term as rooted in semi-sacred myth and history. Although the

Motul dictionary lists a material item that seems to lack such associations—maya

ulum… “gallina…de yucatan”; and “gallina de la tierra”: ulum: mayaulum—in the

references Mayas make to turkeys and chickens in their testaments I have never once

seen lum qualified by maya; on the contrary, Mayas tend to qualify the imported

fowl, the chicken, as caxtillan u lum, “Castilian turkey,” abbreviated by the seven-

teenth century to cax (Ciudad Real n.d., 1: folio 287v; 2: folio 119v; Arzápalo Marín

1995, 1: 489; Restall 1997a: 125–26, 181, 365, 370).

3

The purpose of a dictionary like

the Motul was for Franciscans to make themselves comprehensible to Mayas, and

Mayas would certainly have understood maya u lum. But Mayas themselves would

have used lum for “turkey” and the qualified or invented term for “chicken;” this

would have been more logical from their perspective and consistent with the more

esoteric associations of maya.

Equally rare, and comprising the fourth category in Table 1, are instances where

“Maya” refers to people. As references are so few, patterns can only be tentatively

identified. But the examples suggest that the term was mostly applied by Mayas to

Maya “others” or outsiders, specifically Yucatec natives of another region or class.

One usage in this context was by nobles in reference to commoners, with the term

68 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 68

seemingly somewhat derogatory. Thus when applied to Mayas of another region,

the term sometimes implied that such people were of lesser status, although at other

times the reference seems neutral. Native perspectives on the Spanish Conquest are

the context for one such set of derogatory references, with “Maya” being designated

to the natives of communities who were slower to accommodate the invaders.

The Pech nobles, for example, authors of one Conquest account, assert that they

and their Spanish allies suffered much “because of the Maya people (maya uinicob)

who were not willing to deliver themselves to God (Dios)” (that is, surrender them-

selves to the new colonial regime); these maya uinicob are ambiguously either local

commoners or natives to the east of the Pech region, or perhaps both (Title of Chicx-

ulub, folio 15, from my translation in Restall 1998a: 124). A similar perspective is

found in the Relaciones Geográficas from Valladolid, a Spanish account based partly

on oral native sources, which claims that the natives of Chikinchel (in the penin-

sula’s northeast) called the Cupul and Cochuah (of the east and southeast) “Ah

Mayas, insulting them as crude and base people of vile understanding and inclina-

tion (soez y baja, de viles entendimientos e inclinaciones)” (RHGY, 2: 37).

This pattern incorporates the use of the term as a self-reference (the fifth and

final category in Table 1), in that the context in some of those cases is that of peti-

tions, whose language was by tradition self-deprecating. This tradition was

Mesoamerican in scope, being most clearly visible in petitions in Nahuatl and

Yucatec Maya. One of its central tropes was the presentation by nobles of themselves

as children and commoners. In some Yucatec examples, this self-depiction is paral-

leled by a description of themselves as maya uinicob (Maya people or men). One

group of such attestations is found in a series of petitions authored by cahob across

the whole colony in 1668–69, in response to residencia activities by Spanish offi-

cials—an investigation, in other words, into a governor’s term of office. In this case,

the administration under review was that of don Rodrigo Flores de Aldana, whose

use of forced purchase operations had made him especially unpopular among

Mayas and some colonist groups too. However, to view these attestations as simple

indicators of ethnic self-identity would be to remove them misleadingly from their

context. That context was, first, the self-deprecating component of Maya peti-

tionary discourse, and second, the similarity of these petitions across the series, sug-

gesting the use of a template that may have been partly Spanish-authored (with

“maya uinicob” thus a translation of a phrase such as “indios”) but was certainly

aimed at a Spanish audience. Thus by calling themselves “Mayas,” the petitioners

were ritually humiliating themselves within two parallel social structures: a wholly

native one in which “Maya” had negative class and region connotations, and the

other a colonial ethnoracial one in which “Maya” was understood to have meaning

to Spaniards as a marker of ethnic subordination.

4

The region-class-“Maya” nexus has an additional dimension to it, one that fur-

Maya Ethnogenesis 69

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 69

ther undermines the term as a monolithic ethnic designator. This dimension is the

mythical tradition of foreign origin maintained by a number of Maya noble fami-

lies—all families in the group of prominent ruling chibalob that I have elsewhere

dubbed the “dynastic dozen” (being the Caamal, Canul, Canche, Chan, Che, Chel,

Cochuah, Cocom, Cupul, Iuit, Pech, and Xiu) (Restall 2001). Scholars have tended

to take this tradition at face value, as simple historical evidence of the non-Yucatec

(usually central Mexican) origins of the peninsula’s native elite. However, there is no

clear evidence beyond the tradition itself of any such invasion or migration. Fur-

thermore, the metahistorical construction of the tradition by Maya dynasties con-

forms to the patterns of traditions of mythical elite foreign origins elsewhere in the

world (as studied, for example, by Mary Helms; see Helms 1993; 1994; 1998; also see

Henige 1982: 90–96). I have argued, therefore, that this tradition was not rooted in

an historic migration of ruling families into Yucatan, but rather in pre-colonial

efforts to bolster legitimacy of status and rule through sacred, mythic associations

with often-fictional distant places of origin (for the full development of this argu-

ment, see Restall 2001). These efforts were given renewed necessity and vitality by

the Spanish Conquest, resulting in the frequent references to such mythic origins in

sixteenth-century sources (for example, in the Title of Acalan-Tixchel, folio 69v, The

Title of Calkiní,p.36, the Book of Chilam Balam of Maní,p.134, and RHGY, 1: 319;

see Restall 1998a: 58, 101, 140, 149). By claiming to be both native and foreign, Maya

dynasties effectively problematized and undermined any incipient sense of Maya

ethnic identity that may have otherwise developed in late post-classic and colonial

times. In permitting and often fostering the survival of a Maya élite, Spaniards

thereby colluded in the perpetuation of an identity differentiation that ran against

their impulse to see natives as an undifferentiated mass—and served to soften the

impact of that impulse on Maya ethnogenesis.

All the attested self-references of Mayas as “Maya” come from the regions of the

west, seemingly confirming Munro Edmonson’s suggestion (based on his reading of

the Chilam Balam manuscript from Chumayel) that the Mayas were deemed to be

the inhabitants of the peninsula’s west and the Itzas those of the east. However, the

vast majority of extant colonial Maya sources come from the peninsula’s west, skew-

ing the evidence. Furthermore, Edmonson’s translation of maya ah ytzae as “O

Maya / And Itza” (1986: 100) is more likely “those Itza Mayas” (or “Oh Maya Itza,”

as Ralph Roys has it; 1993: 167). Elsewhere in the Chumayel manuscript the Yucatec

language is called u than maya ah ytzaob,“the language of the Itza Mayas,”again sug-

gesting that Maya and Itza were not always mutually exclusive categories (Roys 1933:

40; Edmonson 1986: 222).

The regional association, therefore, of Mayas with the west and Itzas with the

east is suggested but not very well supported by this evidence. In some ways, the cat-

egory of “Itza” is comparable to that of “Maya”; both are ambiguous, used variously

70 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 70

and usually to describe some other group of natives within the peninsula, with

uncertain historical roots but a fairly clear connection to an important ancient city

(Chichén Itzá and Mayapan, respectively). But there is also a crucial difference

between the two terms: Itza was, and still is, a Yucatec Maya patronym;“Maya”is not

and there is no sign that it ever was. Although this could be taken to suggest that

“Itza” connotes family, and “Maya” ethnicity, in fact the difference between the two

is more complex. Whereas “Maya” has various connotations, most of them not

referring to people, “Itza” is a category that primarily refers to people, both in the

family sense (in the form of a patronym) and in an ethnic sense (in the form of the

Itza Mayas of the Peten region of northern Guatemala, whose name may have

derived from the patronym of the kingdom’s founders).

5

Before summarizing the evidence offered by Maya-language sources, it is worth

turning briefly to the evidence of colonial-era dictionaries. This complex, bilingual,

bicultural genre cannot of course be used as a simple window onto colonial Yucatec;

dictionaries merely suggest how Maya was spoken in a particular time and region

in the peninsula, as perceived and recorded by their Franciscan authors. Neverthe-

less, a search for maya entries in colonial dictionaries is revealing, especially in the

context of the evidence from Maya notarial sources discussed above.

As Table 2 shows, there is a clear maya entry in one of the two principal Maya-

Spanish dictionaries of the colonial period (the 16th Century Motul), but it is not

listed as a Maya term in the late-colonial grammar by Beltrán. The term supposedly

appears once in the Maya-Spanish section of the San Francisco dictionary—to qual-

ify bat, meaning “axe”—but the original manuscript of this dictionary was a 19th

Century copy that is now lost and so its 17th Century origins remain speculative

(Barrera Vásquez 1980: 25a-27a, 513). Only in the Spanish-Maya sections of colonial

dictionaries does the term appear with any regularity, suggesting that while the term

certainly existed in colonial Maya, it was not one commonly used by Mayas. The

types of applications of the term in Spanish-Maya vocabularies compares closely to

the examples that I grouped under “cultural” and “material” (as opposed to

“human”) in Table 1, implying that to Spaniards too the term was an adjective con-

veying autochthony in a general sense, rather than one specific to human beings.

Indeed, surprisingly “Maya” does not appear in reference to people in the Spanish-

Maya volume of the sixteenth-century Motul manuscript, even though it does in the

Maya-Spanish volume. Such an entry first appears in Spanish-Maya lists half way

through the colonial period, in the Vienna vocabulary of the late 17th Century, and

perhaps also in the San Francisco dictionary, which may date from the 17th Century

too. But maya does not appear in reference to people either in Beltrán’s grammar of

1746 (in which the language is “el Idioma Maya,” “la Maya,” and “el Idioma

Yucateco,” but its native speakers are “Indios” and “Naturales”) or the Ticul compi-

lation of 1836, suggesting it remained uncommon as an ethnic designator through

Maya Ethnogenesis 71

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 71

the end of the colonial period (Ciudad Real n.d.; Arzápalo Marín 1995; Beltrán 1746;

Pío Pérez 1898;Mengin1972: folio 131v; Barrera Vásquez 1980: 513).

6

What can be concluded, therefore, from the evidence discussed so far and pre-

sented in Tables 1 and 2? First, “Maya” is not a common term in colonial Maya

72 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

table 2

Colonial dictionary attestations of the term maya

cen- dictionary in ref. to in ref. to cultural/ in ref. to

tury the language material objects people

16th Motul (Maya-Spanish) 333

17th? San Francisco (Maya-Spanish) 3

18th Beltrán (Maya-Spanish)

16th Motul (Spanish-Maya) 33

17th? San Francisco (Spanish-Maya) 333

17th Vienna (Spanish-Maya) 33

18th Beltrán (Spanish-Maya) 3

19th Ticul (Spanish-Maya) 3

Sources: Ciudad Real (n.d.); Beltrán (1746); Mengin (1972: folio 131v) (the edition is a facsimile

reproduction that uses the folio numberings of the original manuscript); Solís Alcalá (1949).

Notes: The maya entry in Ciudad Real (n.d.) is on f. 287r of vol. 1, which corresponds to Arzápalo

Marín (1995, 1: 489). The relevant entries in the Spanish-Maya volume of the Motul, the original

manuscript of which remains unpublished, are “gallina de la tierra: ulum: mayaulum” (vol. 2,f.

119v) and “lengua de esta tierra o prouincia de yucatan: mayathan” (vol. 2,f.141r); the phrase “esta

lengua: de maya” appears on f. 134r. Folio 233 of vol. 2 of the Motul (the unpublished Spanish-Maya

volume) is missing from the original manuscript; two of the uses of maya found in the Book of

Chilam Balam of Chumayel (see Table 1 above) would have been on this folio under “vino maya”

and “virgen maya”if they were included by Ciudad Real (the Maya terms used in the Chumayel are

not in the Motul’s Maya-Spanish volume).

The frontispiece to Beltrán (1746) states that the work was written in Mérida in 1742; I consulted

the copy in the JCBL (B746/B453a), which contains marginalia hand-written by Beltrán himself.

Beltrán’s book is not a dictionary, but a grammar containing numerous brief vocabulary lists; thus

to be sure I did not miss anything, I also checked the tabulation of Beltrán’s lists in Pío Pérez (1898);

maya is conspicuously absent on p. 51. It appears in the Spanish-Maya portion of the coordinación

(which is Pío Pérez’s edition of the Ticul) in reference to language on p. 220, but I could find no

other attestations. The entry in my table under “Beltrán (Spanish-Maya)” is based on his book’s

title and text, in which the native speakers are “Indios,” never “Mayas.”

Solís Alcalá (1949) drew mostly upon the Motul and Pío Pérez’s vocabularies, and Barrera Vásquez

(1980: 513), which was my sole source on the San Francisco (for the others, I also consulted the orig-

inals). According to the Cordemex, the only entry in the Maya-Spanish San Francisco that includes

the term maya is “maya’ bat: hacha de las de esta tierra con su cabo a lo antiguo.”

A note on dates: The Motul dates from c. 1577, the San Francisco possibly from the seventeenth cen-

tury and the Vienna the late seventeenth century, the Beltrán was first published in 1746 (I have

used Pío Pérez’s edition of 1898), and the Ticul compiled in 1836.

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 72

sources. Second, it was primarily used to refer to the Yucatec language or to native

material items, the latter primarily ones with sacred and/or historical associations.

Third, when it was applied to people, it was never done so in a way that explicitly

indicated a peninsula-wide or macroregional ethnic identity, suggesting instead

smaller groups defined by region or class, with the term very possibly deriving from

the toponym “Mayapan.” Dictionary entries of the term as a macroregional ethnic

one are irregular, with no colonial dictionary including it in both a Maya-Spanish

and Spanish-Maya vocabulary; its more common dictionary meanings are in refer-

ence to the Yucatec language and to local material items. Fourth, such implications

of “Maya” group identity are inconsistent and contradictory. Fifth, there are signs

that the term may have been viewed by Mayas as derogatory and/or as an archaic

historical or literary term.

A Maya By Any Other Name?

If Mayas therefore did not see themselves as “Mayas,” what were the foundations of

native self-identity? In addition to expected micro-identities such as gender, age,

class, and occupation, there were two fundamental units of social organization

which served as the basis of group and individual identity for colonial Mayas—the

municipal community (which the Mayas called the cah), and the patronym-group

(which they called the c

ibal). Mayas organized their lives and activities around

these two units and consistently identified themselves and other Mayas according

to cah and c

ibal affiliations.

The cah was a geographical entity, consisting of its residential core (what we

would call a village or town) and its agricultural territory (the combination of the

cultivated and forested lands held by cah members). But it was also a political and

social entity, being the focus of Maya political activity (regional politics was a Span-

ish monopoly during colonial times), and the locus of social networks. At the pri-

mary level of the extended family, identity and social activity was generated at the

meeting point of cah and c

ibal—built, in other words, around the members of a

particular cibal in a particular cah. As cibalob were exogamous (in accordance

with a deep-rooted Maya taboo that was broken only occasionally by dynastic-

dozen couples), their members tended to form multi-cibal alliances that were

inevitably class-based and related to political factionalism in the cah. As almost

every aspect of a Maya individual’s life was determined by cah and cibal affilia-

tions, it is not surprising that these units formed the native identity nexus, and pro-

vided the references for identification; thus someone might be Ah Pech or Ah

Pechob, “of the Pech [cibal],” and Ah Motul,“of Motul [cah]” (Restall 1997a: 15–50;

1998b: 355–81).

Maya Ethnogenesis 73

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 73

One might argue that cah and c

ibal formed the basis of a kind of ethnic iden-

tity, or a multiplicity of micro-ethnic identities, a notion reminiscent of an older

historiographical tradition that saw the pre-Conquest Mayas as divided into vari-

ous “tribes.”

7

Furthermore, if all Mayas shared the same type of identity, as well as

sharing the experience of colonial subjection, then arguably they shared a kind of

aggregate ethnic identity.

8

This argument is not altogether without merit, but it is

hard to reconcile with the three fundamental aspects of Maya identities: the persist-

ence of class differences within each cah, as discussed above; the open nature of the

cah (in that it was exogamous, permitted settlers from other cahob, and was part of

the complex pattern of Maya mobility, the cah was not a closed community); and

the diasporic nature of the cibal (that is, members of each cibal were found in a

variety of cahob, almost never in just one, and often not even in a single region).

Thus to categorize cah and cibal as types of ethnic identity would seem to stretch

the term too far.

Nevertheless, as tempting as it may be, the issue cannot simply be left tied up in

the tidy parcels of cah and c

ibal. Colonial circumstances made Maya identity

increasingly more complex than that. After all, however rarely or irregularly the

Mayas used the term “Maya,” it was never used to describe a person or object from

outside the peninsula (see Table 3). Furthermore, cahnalob, or cah members, were

74 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

table 3

Maya terms of self-description containing ethnic implications

term, with variants meaning context of usage

ah cahnal, cahnal, (ah) cahal cah member, all genres, non rhetorical, often

/cahalnal, h cahala [late] resident juxtaposed to vecino (“Spaniard”)

ah otochnal householder, native same as ah cahnal

macehual, masehual commoner rhetorical usage implying “Maya”

mehen (man’s) children same as macehual

almehen noble only to describe Maya nobility

uinic man, person sometimes means (Maya) person

kuluinic, u nucil uinic, a principal, or Maya person only

noh uinic elder

maya uinic Maya man/person rare; quasi-notarial sources only

maya than Yucatec Maya the language

ah [cah name] person of [cah] Maya person only

ah [patronym] person of [cibal] Maya person only

Sources: Adapted from Restall (1997: 17), based on colonial Maya-language notarial and quasi-

notarial sources.

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 74

never non-Mayas, nor could cibalob, or members of a particular cibal be non-

Mayas either. Another Maya term, macehual, which primarily meant “commoner,”

came to take on ethnic implications in the colonial period because Spaniards and

Africans could not be macehualob. As Table 4 shows, by the mid-eighteenth century

macehual appears in a Maya-Spanish dictionary glossed as indio, having been omit-

ted entirely from earlier dictionaries. Corresponding to terms that were applied

only to Mayas were terms applied only to non-Mayas, such as dzul (written

ɔ

ul in

colonial orthography), “foreigner,” and the Spanish word vecino, “resident,” which

was mostly used by Spaniards, and occasionally by Mayas too, to refer to non-Mayas

(Restall 1997a: 15–16; 1997b: 239–67; Karttunen and Lockhart 1987; Lockhart 1992:

86–89, 365–68).

However, it would be a mistake to assume that “macehual”was effectively a colo-

nial cognate for “Maya” as used today (as Hervik seems to suggest; 1999: 39, 42). The

absence of “macehual”from colonial Spanish-Maya vocabularies and the consistent

defining of “dzul”in colonial dictionaries as “foreigner,” rather than “Spaniard,” sug-

gests that “macehual” and “dzul” did not become terms of ethnic identity compara-

ble to the meaning we assign to “Maya” and “Spaniard.” In Table 3 I have denoted

the “context of usage” of “macehual” in Maya-language sources as being a rhetori-

cal one “implying ‘Maya’,” because Maya nobles typically styled themselves com-

moners in petitions to Spaniards, as a political ploy and in accordance with

Mesoamerican techniques of deferential discourse, in a way that was similar to their

usage of “Maya” as an identity marker. Spaniards read such terms as ethnoracial

because they defined the colonial social structure ethnoracially; Maya elites contin-

ued to see “macehual” as a class term, because the social structure from their per-

spective was primarily a local one of Maya nobles and commoners, and only

secondarily a colonial one featuring non-Mayas too. The fact that Spanish officials

read “maya” and “macehual” as “indio” was probably not lost on the Maya elite;

indeed, this contributed to the efficacy of their rhetoric and its adaptation to the

colonial setting. But that does not mean that native elites thereby adopted Spanish

perspectives and internalized the Spanish perception of them as Indians.

Nevertheless, the appearance of “macehual” in colonial sources cannot simply

be dismissed any more than “maya” can. Mayas did not see themselves as “Maya” or

any other term or label that contained all natives in the peninsula, but the evidence

of Tables 3 and 4 suggests that Mayas did develop during colonial times an aware-

ness of difference that more or less corresponded to Spanish ethnoracial distinc-

tions. More specifically, this awareness can be better understood if we draw a

distinction between two forms of ethnic awareness: overt ethnicity, whereby mem-

bers of an ethnic group clearly identify themselves as such; and implied ethnicity,

whereby terms of self-identification imply membership in a loosely-defined ethnic

group within the context of broader social and ethnoracial structures. Colonial evi-

Maya Ethnogenesis 75

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 75

dence indicates that the colonial experience gave rise to and fostered a sense of

implied ethnicity among the Mayas who lived within the Spanish province, but that

overt ethnic awareness among Mayas did not exist in either the late post-classic or

colonial periods.

One dimension of this terminological bifurcation is the role played by ethnic

boundaries: Maya terms of implied ethnicity are mostly inward looking and con-

cerned with social life in the cah; overt ethnic markers tend to be outward-looking

and reflect a keen awareness of ethnic borders.

9

Jon Schackt proposes that “ethno-

genesis should mean the drawing of new boundaries or, perhaps, some notable

redrawing of old ones” (2001: 4). The boundaries that defined community and

identity among Yucatec Mayas were not notably redrawn during the colonial

period, nor were new boundaries created; such boundaries continued to demarcate

one cah, or group of cahob, from another, without expanding outward to include

the natives of all cahob.

By adding to the above analysis of Maya-language sources a reading of Spanish-

language notarial sources from the colonial archives, it is possible to be more spe-

76 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

table 4

Colonial dictionary attestations of the terms macehual and dzul

century dictionary macehual dzul

16th Motul (Maya-Spanish) — extranjero

17th? San Francisco (Maya-Spanish) — —

18th Beltrán (Maya-Spanish) indio [forastero]

16th Motul (Spanish-Maya) — advenedizo

17th? San Francisco (Spanish-Maya) — —

17th Vienna (Spanish-Maya) — —

18th Beltrán (Spanish-Maya) — forastero

19th Ticul (Spanish-Maya) — —

Sources: Ciudad Real (n.d., 1: folio 133r), which corresponds to Arzápalo Marín (1995, 1: 222); Bel-

trán (1746); Pío Pérez (1898: 51, 101); Barrera Vásquez (1980: 503); Mengin (1972).

Notes: I could not find macehual in the Spanish-Maya volume of the Motul manuscript in any

entries referring to people, but it does appear in the compound form “vulgar lengua: maçeualthan”

(vol. 2,f.235v). The Cordemex (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 503) lists “masewal ki’: vino de la tierra” as a

Beltrán attestation, but I could not find it in Beltrán or the Pío Pérez edition cited in the Corde-

mex.TheCordemex also cites the Spanish-Maya portion of the San Francisco in support of the

macehual entry, but gives no specific attestation, leaving it unclear as to what form, if any, such an

entry takes. I found “forastero.

ɔ

ul” in a Spanish-Maya list in Beltrán (p. 182) but could not find in

Beltrán the reverse entry included by Pío Pérez (hence its inclusion in my table in brackets). I have

modernized the spellings of extranjero, forastero, and advenedizo, which all mean “foreigner”(with

the last having a connotation of “interloper”).

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 76

cific still in locating the colonial conditions under which implied, but not overt, eth-

nic awareness developed. Such sources stem mostly from conflict of some kind,

being criminal cases, Inquisition files, land disputes, and investigations into alleged

political and other abuses within or against the cahob (to be found in various sec-

tions of the AGI, AGN, and AGEY). A survey of such sources reveals three pertinent

types of condition. The first is the colonial legal system itself. Its often-skillful

manipulation by cah leaders suggests that one important reason for this bifurcated

development was the Maya realization that colonial identities and their various

facets could be used as weapons in law courts or as tools to work away at the struc-

tures of colonial administration. Under these circumstances, ethnic identity

remained implied most of the time, becoming or seeming overt in rare moments of

legal strategy.

The second colonial condition was the growing difference between urban and

rural Maya communities. In rural cahob, identity remained rooted in community

and family affiliations, as discussed above. Colonialism reinforced this localization

of identity, through its suppression of regional native politics; or, to borrow terms

used recently by Natividad Gutiérrez in a more general context,“nondominant eth-

nic cultures ...beyond the level of the village, lack the means to engender cohesion

and to construct and reproduce homogenized meanings” (1999: 50). But in the city

of Merida and the colonial towns—the villas of Bacalar, Campeche, and Valladolid,

and the pueblos that became semi-urbanized towards the end of the colonial period,

such as Izamal—Maya identity developed urban variations on the implied/overt

model. The multiracial setting and the concomitant process of miscegenation made

Maya ethnic identity increasingly overt in late colonial decades; in the compact

world of differences that was the colonial Yucatec city or town, some Mayas became

something close to “Maya.” At the same time there developed a form of implied

native identity among mestizos or castas of mixed-Maya descent—the colonial gen-

esis of the Maya-mestizo identity to be found in present-day Yucatan and frequently

the subject of scholarly discussion (Hostettler and Restall 2001; this issue of JLAA).

Urban developments, therefore, incorporate the third condition under which

implied ethnic awareness developed rather than overt ethnic self-identity. This was,

simply put, the effect of time. My hypothesis regarding the chronological develop-

ment of the use of the term “Maya,” and its implications for Maya ethnogenesis or

ethnic identity, is the following.

In the late postclassic period, the term applied to all or some of the inhabitants

of Mayapan; after that city’s collapse in the 1440s the term applied to the Diaspora

of families who migrated to various locations in the peninsula, but its application

seems to have been vague and probably increasingly obscure as such families did not

maintain identities that were clearly distinct from other local families. At the time

of the Spanish invasion, its primary use was probably in reference to the Yucatec lan-

Maya Ethnogenesis 77

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 77

guage, in the form mayathan. By the late 16th Century the term was being applied

both to the Yucatec language and to local material items, but not to people, and even

then it seems to have been more commonly used by Spaniards than Mayas. At the

same time, there remained no other term in Yucatec Maya equivalent to our under-

standing of “Maya” as an ethnic designator; Maya identity remained more localized

than that, lacking a clear ethnic component.

As the colonial period wore on, a sense of implied ethnic identity evolved in

response to colonial conditions and the influence of Spanish efforts to build a colo-

nial society based on ethnoracial principles. In the late 17th Century the written

record reveals evidence of “Maya” being used in reference to people, but attestations

are rare and dictionary entries are only in the Spanish-Maya listings. More common

in the late-colonial period is the term macehual, but its transition from an exclu-

sively class term to an exclusively ethnoracial one was gradual and not complete by

the end of colonial rule. By the early 19th Century, with the possible exception of

urban variants mentioned above, there is little sign of this implied ethnic identity

having become overt.

Towards a Conclusion: Ethnogenesis as a Tug-o’-War

If the colonial Maya evidence supports the notion of a highly muted sense of eth-

nic identity among Yucatec Mayas by the early 19th Century, why have they been

assigned such an identity with such regularity over the past five centuries? I have

already alluded to one of these—colonial Spanish influence—but I would like to

restate it more fully and in the context of a chronology of three historical develop-

ments that have pulled Mayas towards a “Maya” identity even as they themselves

have continued to resist that tug.

Spanish influence is of course rooted in the mid-sixteenth century, when

repeated Spanish invasions finally resulted in the permanent establishment of a

small colony in the peninsula. Directed by a presumptuous geography and a cava-

lier ethnocentrism, Spaniards imposed upon hundreds of native groups in the New

World a blanket racial identity, that of indio, which indigenous peoples neither

shared nor ever came to embrace.

10

At the same time, Spaniards imagined that the

“Indians” of particular regions, such as Yucatan, had a regional sense of identity that

gave them particular characteristics in common.

Such characteristics were based less on proto-ethnographic observation—

investigations such as Diego de Landa’s into native culture were the exception rather

than the rule

11

—and more on explaining phenomena related to the Spanish expe-

rience. For example, the protracted nature of the Conquest—twenty years to estab-

lish a permanent hold on a mere corner of the peninsula (Clendinnen 1987; Restall

78 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 78

1998a)—was put down to Maya bellicosity and duplicity, a paradigm that remained

an undercurrent to Spanish discourse on Mayas throughout colonial rule and one

that would resurface with vehemence during the Caste War. Clendinnen quotes the

conquistador Francisco de Montejo who wrote to the king in 1534 that Yucatan’s

“inhabitants are the most abandoned and treacherous in all the lands discovered to

this time, being a people who never yet killed a Christian except by foul means....

In them I have failed to find truth touching anything” (1987: 29). Montejo’s words

echoed three centuries later, in 1848, when, according to Chuchiak, the Spanish

Yucatecan Justo Sierra O’Reilly denounced the Mayas as “brutal, scheming, warlike

savages, whose goal is nothing less than the destruction of civilization”(1997: 25).

12

Spaniards thus assigned the Yucatec Mayas what was in effect an ethnic identity,

bounded by regionalism—in this case a colonial province that more or less com-

prised the peninsula of Yucatan—and by perceived characteristics such as those

cited above or those recorded by Landa.

13

Within the larger schema of the colonial

Spanish sistema de castas or ethnoracial “caste” system, constructed ethnic groups

such as the Yucatec Mayas comprised the racial category of “Indians.” The impor-

tance of the latter—with “Indian” characteristics being more significant than

regional ethnic ones—was reflected in Spanish terms of reference; native groups

were usually “the Indians of this province” or “the Indians of that land,” with more

specific references being geographical (Landa sometimes refers to los yucatanenses;

1959: 47, for example) or externally determined (there are so-called Chontal groups

around the margins of the regions that were Nahuatl-speaking in the 16th Century

because chontalli is a Nahuatl term for “foreigner”).

“Indians,” as a subordinated but semi-civilized source of labor, slotted into the

ranking of the ethnoracial system between Spaniards, who as “people of reason”

were destined to rule,and Africans, whose “inherent inferiority”suited them to slav-

ery. Because these “natural laws” were part of an evolving European ideology of

colonial justification, they had to be realized through a complex mixture of force,

coercion, and co-optation. Furthermore, for the same reason, the system was never

fully realized, leaving scholars of colonial Spanish America to struggle with the

complex contradictions between colonial Spanish assertions and historical evi-

dence on the nature of societies in these colonies. Some historians have argued that

the Spanish-“Indian”-African ranking based on phenotype was, when it came to the

functioning of social organizations, a Spanish-African-“Indian” system (Lockhart

and Schwartz 1983: 130). Others have argued that the growth in the mixed-race pop-

ulation, the people to whom the term castas properly refers, created a social struc-

ture in which class played a more significant role than race (most notably Cope

(1994), but also see Boyer (1995) and Stern (1996), as well as additional citations on

the race-class debate in Kellogg (2000)). The point to be emphasized here is that

there was, from the start and increasingly so, a disjuncture between social and cul-

Maya Ethnogenesis 79

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 79

tural realities on the one hand and colonial Spanish constructions and perceptions

of ethnoracial identities on the other. One part of this phenomenon was the inven-

tion of an ethnic group of Yucatec “Indians,” later becoming Yucatec “Mayas,”

within the larger race of New World “Indians.”

The second historical development that acted as an external force pulling Mayas

towards an ethnogenesis was the conflict that began in Yucatan in the 1840s as a civil

war and was during the course of 1847 recategorized and labeled as a “caste” or race

war by the peninsula’s Hispanic leaders. In a long historical and historiographical

tradition, running from Justo Sierra O’Reilly (see his 1848 quote above) to Lazaro

Cárdenas, Nelson Reed, and Don Dumond, the war actually became a race war, with

vengeful Mayas almost regaining the lands taken from them by invading Spaniards

and their descendents (Reed 1964; Dumond 1997; also Bricker 1981).

14

The counter-

view, articulated most notably by Terry Rugeley, is that divisions of region and class

played more important a role than ethnic or racial antagonisms (Rugeley 1996;

Cline 1947;Patch 1991). Questions of Maya ethnic identity are obviously at the heart

of this debate, in the light of which my argument above on colonial Maya identity

has two possible applications. One is that the colonial-era development of multiple

implied-ethnic terms laid a foundation for a Maya ethnogenesis during the Caste

War. The other is that the bifurcation of implied and overt ethnic awareness per-

sisted through the mid-19th Century, with the war failing to foster an ethnogenesis.

My position is the latter; indeed, I would go so far as to suggest that Caste-War evi-

dence demonstrates that a Maya ethnogenesis did not take place in Yucatan before

1850.

As the 19th Century is primary neither to this article nor my expertise, I prevail

upon the reader to accept a mere sample piece of evidence to support this assertion.

In the “Proclamation of Juan de la Cruz” of 1850, the cruzob author refers to his fol-

lowers either in paternal terms, as “my children” (in sihsahbilob, literally “my prog-

eny,” and in sihsah uincilob, “my engendered people”), or in the same terms of the

implied—not overt—ethnic awareness of the colonial period (Cristiano Cahex,

“you Christian cah members,”and maseual, “commoner [by implication, native],”

or in sihsah maseualilob, “my commoner progeny”). Ethnic divisions are strongly

implied—at one point Cruz lists four implied-ethnic groups, those of dzul,(“for-

eigner,” by implication, Hispanic),” box (“black”), maseual (“commoner,” by impli-

cation, native), and mulato—but the terms “indio,” “indígena,” or “Maya” never

appear and the bifurcated sociopolitical world of the letter seems to be between

Cruz’s community “children” and their “enemies” (enemigoob) (letter in Bricker

1981: 187–207; glosses mine. The same language was used in Cruz’s 1851 letter to

Governor Barbachano; op. cit.: 208–18).

This example and its analysis has been chosen in part for reasons of method-

ological consistency with the philological analysis of colonial Maya terms above. It

80 The Journal of Latin American A nthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 80

has also been chosen as a bridge to the article by Wolfgang Gabbert that follows in

this issue of JLAA. That article, viewed in the terms of this one, argues that ethnic

identity did not create the two sides in the war, because ethnic divisions did not

characterize the make-up of its combatants or victims. The intense period of war

(from 1847 to about 1853) was followed by a half century in which Yucatec Mayas

were as divided as they had ever been, with numerous native groups (cruzob, differ-

ent pacifico groups, and so on) existing at various points along a spectrum between

full incorporation into the Mexican state of Yucatan and complete autonomy.

Whatever impact the intense mid-century conflict may have had on generating a

macehual ethnic identity, the subsequent decades broke down macro-regional

macehual identity as so-called pacifico groups began to call themselves mestizos

and the so-called bravos or cruzob rebels proclaimed themselves macehualob in dis-

tinction to the “pacified” Mayas (Hervik 1999: 42–46; Dumond 1997; Castro 2001;

Gabbert 2004: Part ii). This political situation was partly a result of the state’s inabil-

ity to establish direct rule over the whole peninsula, but it also represented continu-

ity in terms of the localized nature of Maya identities and reflected the fact that the

discourse of the rebels was not built upon the kind of ethnopolitical ideas that have

underpinned the late-20th Century ethnogenesis in Guatemala.

This brings me to the third historical development that helps explain why Mayas

have been so consistently assigned an ethnic identity; this is the process that coa-

lesced in the 1960s and has been dubbed “ethnopolitics”by political scientist Joseph

Rothschild. The ethnopolitical process mobilizes ethnicity for the political purpose

of “altering or reinforcing ...systems ofstructured inequality”between groups, and

in doing so “stresses, ideologizes, reifies, modifies, and sometimes virtually re-cre-

ates the putatively distinctive and unique cultural heritages of the ethnic groups that

it mobilizes”(Rothschild 1981: 2–3). In other words, ethnopolitics fosters ethnogen-

esis. In the context of this late-20th Century ethnopolitics, and specifically with

respect to the Mayas, a modern Maya ethnic identity has been forged by Mayas and

their non-Maya allies, complete with constructed historical roots, for the purposes

of mobilizing the mostly-Maya underprivileged.

Guatemala offers a more vivid example of this process than Yucatan, partly

because “Maya” appears to have been imported into the region from Yucatan by

19th-Century archaeologists (Schackt 2001: 7–8),and partly because of the late-20th

Century civil war in Guatemala; modern ethnopolitics marks one important differ-

ence between that civil war and Yucatan’s earlier Caste War, the ethnopolitics of

which resulted not in a pan-Maya movement but in a splintering of rebel Mayas into

the distinct groups mentioned above (Carmack 1988; Smith 1990; Wilson 1995;

Watanabe 1995; 1997;Warren 1998;Wellmeier 1998;Montejo1999; also see Fried-

man 1992). The fact that “Maya” identity is a late-20th Century development in

Guatemala is underscored by Sol Tax’s assertion that in the 1930s the “municipio”

Maya Ethnogenesis 81

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 81

delineated “the basic ethnic divisions and cultural groups into which the country is

divided” (1937: 425).

15

However, the process is also visible in Yucatan, where, in the

decades following the Revolution of the 1910s elsewhere in Mexico, non-Maya

Yucatecans sought to exploit a reconstructed Maya heritage for symbols of regional

identity (Castañeda 1996: 108–9). Yet in both regions, political circumstances gave

rise to a Maya ethnogenesis gradually and unevenly. As Jon Schackt has observed,

with respect to both Guatemala and Yucatan, “until recent years most so-called

Mayan Indians have been unaware of their common ‘Mayahood’ ” (2001: 3). When

Fischer comments that “identifying oneself as Maya rather than a person from town

X or a speaker of language Y no longer raises eyebrows in Tecpán and Patzún,” he is

drawing upon fieldwork conducted in Guatemala as recently as the 1990s (2001:

245).

The sum, then, of these three phenomena—Spanish ethnoracial concepts that

developed in the 16th Century, the rhetoric of race and polarizing violence of the

Caste War, and 20th-Century ethnopolitics—has been, to paraphrase the

Comaroffs (1992: 61), a process of reification that has given Maya ethnic identity the

false appearance of being an independent factor in the ordering of the Yucatec social

world.

While non-Mayas consistently saw “Indians” and “Mayas,” the Mayas them-

selves held to their own less monolithic identities. Schackt has expressed concern

that his position “that Maya identity is not ancient but under construction in the

present” might be taken as suggesting it to be “spurious or inauthentic” (2001: 10).

His fear is not groundless; at a recent panel discussion, my assertion of the same

argument was taken as showing “lack of respect” for Mayas, a reaction that supports

the very point that Maya identity is presentist and politically—rather than histori-

cally—rooted.

16

As Schackt observes (2001: 10), construction or invention does not

imply inauthenticity, as invention is “a necessary dimension of all cultural

processes.” Crucial to understanding the cultural process of Maya ethnogenesis in

the 20th Century—and my argument that such an ethnogenesis did not occur in

previous centuries—is an understanding of how that process is rooted in both 20th-

Century politics and an invented ancient Maya identity (hence the current Maya

“revival,”“renaissance,” and “resurgence”).

17

In between those modern and ancient

points lie three or four centuries of “Maya” history during which Maya peoples

refused to accept categories of identity assigned to them, be it indio or Maya. In a

sense, then, the Maya struggled for centuries in the face of steady opposition against

their own ethnogenesis.

18

82 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 82

Acknowledgments

An initial, briefer version of this article was presented as a paper on the March 2000

LASA/Miami panel “Rethinking Maya Identity in Yucatán, 1500–1940.” Another briefer and

somewhat different version, titled “The Janus Face of Maya Identity in Post-Conquest

Yucatan,”is included in Hostettler and Restall (2001: 15–23). I am grateful to Robert Carmack,

Quetzil Castañeda, Ben Fallaw, Wolfgang Gabbert, Ueli Hostettler, James Muldoon, and

anonymous readers for comments made on earlier versions of the paper and article.

Notes

1

Bricker et al record the variant of mayab’-t’àan (mayab’ is entered in the same dictionary as “flat”).

2

A similar statement is made in the relación of “Quinacama” (1: 254). Wolfgang Gabbert comes to

the same conclusion regarding the origin of the term (2001: 25–34). Munro Edmonson remarks that “the

modern name of the Maya may be derived from Mayapan” (1982: 10), but he cites Alfred Tozzer, who

merely states that the peninsula was called “Maia” without speculating as to the term’s etymology (1941:

7, 9); later Edmonson suggested that the name was derived from the may cycle of 13 katuns (1986: 5, 9),

a theory that Castañeda finds persuasive (1996: 13).

3

The earliest attestation of cax that I have seen is mid-17th Century; by Beltrán’s time, it had become

a dictionary term—“Gallo de Castilla Ahcax” and “Gallina de Castilla Yxcax” (Beltrán de Santa Rosa

1746). One could argue that turkeys did have sacred associations, as they were traditionally used in sac-

rificial rituals; but that does not mean that turkeys were always imbued with sacred significance. Such an

argument is stronger with respect to the maya bat entry in the 17th-Century San Francisco dictionary, as

maya is clearly being used here to describe something historically distant and possibly with vague sacred

associations—an ancient “Maya axe,” as opposed to the metal axes that Mayas had been using for a cen-

tury by the time this dictionary was compiled (see mention of this entry, the dictionary’s dating, and cita-

tions below).

4

On petitionary discourse among Mayas and Nahuas, see Restall (1997b: 255–59; 1997a: 251–66) and

Karttunen and Lockhart (1987). The 1668–69 petitions are in the AGI (Escribanía 317a, 2, various folios).

For a discussion of possible Spanish and Maya roles in the formulation of a series of petitions in Maya

from a century earlier, see Restall (1998a: 151–68).

5

On the Itzas of the Peten and their Yucatec origins, see Jones (1998: xix, 3–107). This would not be

the only instance of a Maya people adopting as a group or ethnic label the name of a founding ruler or

dynasty; the Quichés did it too (see Hill and Monaghan 1987: 32–33).

6

Juan Martínez Hernández also published an edition of the Motul in 1931, but, as William Gates

observed in a review, it was so riddled with errors of transcription—over a hundred in the first ten pages

alone—as to be “nothing short of disastrous” (1931: 93). In contrast, I have yet to note a single transcrip-

tion error in the Arzápalo edition.

7

Robert Chamberlain and Ralph Roys used the term “tribe” (see especially Roys 1943), and their

influence can still be seen occasionally in print; see Rugeley (1996: 8), for example.

8

I am indebted here to an anonymous reader for JLAA, who pointed out the possible applicability

to the colonial period of a piece by Carol Smith (1987), arguing for the compatibility of local commu-

nity identities with an ethnically marked class identity among modern Guatemalan Mayas.

9

The seminal study to demonstrate the central role played by dividing lines between ethnicities in

identity formation was of course Fredrick Barth’s 1969 edited volume. The literature on ethnic bound-

Maya Ethnogenesis 83

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 83

aries since 1969 is too substantial to cite, but two recent studies of the topic as applied to Yucatan by Euro-

pean scholars are Hervik (1999) and Gabbert (2004).

10

Studies of race in modern Latin America tend to make the misleading assumption that modern

categories have exclusively 19th-Century roots (Knight 1990; Stepan 1991), without considering the 16th-

Century impact of the New World discoveries and invasions upon European conceptions of “nations”

and “peoples” (Elliott 1970) and the subsequent development in mid- and late-colonial Spanish Amer-

ica of “modern” notions of race (Kellogg 2000; Cañizares Esguerra 1999).

11

Other Spaniards, almost all Franciscans like Landa, also wrote accounts of Yucatec history that

included discussions of Maya culture, but they tended to devote their attention more to Spanish achieve-

ments, especially those of the Church, and to view Mayas through the prism of their evangelizing,“civ-

ilizing” endeavors; a good example, though unpublished in English, is Cárdenas y Valencia’s 1635

manuscript (in the BL).

12

For another example of racist stereotyping of “Indians,” see the 1845 description of Mayas by the

Yucatec priest Granado Baeza (quoted in Hervik 1999: 38). There are numerous primary and secondary

sources available on the broader context of Spanish attitudes towards various native groups in the Amer-

icas; a primary example already mentioned is Landa (1959: first eleven “chapters”), while secondary

examples include Elliott (1971), Keen (1971), Todorov (1984), and Restall (2003).

13

Landa wrote a vast study of Yucatec Maya history and culture, called, according to its genre, his

Recopilación; the work appears to have been lost in the late-17th Century, with the only surviving traces

being the compilation of excerpts, some of which may not have been written by Landa himself, cited

above as his Relación (see Restall and Chuchiak 2002).

14

On Cárdenas’ interpretation of the righteous role played by the “Maya race” in the war, see Fallaw

(1997: 560–65). See Gutiérrez (1999: 42–44) and Wolfgang Gabbert’s article in this issue of JLAA for more

discussion and references on interpretations of the war as one of “ethnic liberation.”

15

Tax’s analysis is similar to the argument I have made on the centrality of the municipal commu-

nity, or cah, to colonial Yucatec Maya identity and organization (mentioned above,also see Restall 1997a).

Denise F. Brown (1993) similarly emphasizes the role of the cah among present-day “rural” Yucatec

Mayas.

16

Panel on “Ethnicity” at the conference on A Country Unlike Any Other(?): New Perspectives on His-

tory in Yucatán, Yale University, November 2000.

17

Schackt (2001: 12) cites a 1997 Newsweek article, a 1996 issue of the Guatemalan magazine Crónica,

and the title of Wilson (1995) for uses of these terms, respectively.

18

Arguably such a struggle continues through the 20th Century; for example, see Gutiérrez (1999:

54) for a contemporary Maya woman’s reaction to “’being told to be a Maya’ without being sure what it

is to be a Maya.”

References Cited

AGI. Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain.

AGEY. Archivo General del Estado de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatan.

AGN. Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

BL. British Library, London.

JCBL. John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence.

TLH. Tozzer Library, Harvard University, Cambridge.

TULAL. Latin American Library, Tulane University, New Orleans.

84 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 84

Arzápalo Marín, Ramón

1995 Calepino de Motul: Diccionario Maya-Español, 3 vols. Mexico City: Universidad

Nacional Autónoma de México.

Baeza, Br. Granado

1845 “Los Indios de Yucatán,” in Registro Yucateco IV, 165–78.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo, et al.

1980 Diccionario Maya Cordemex. Mérida, Yucatán: Ediciones Cordemex.

Barth, Fredrick, ed.

1969 Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Difference.

London: Allen & Unwin.

Baumann, Gerd

1999 The Multicultural Riddle: Rethinking National, Ethnic, and Religious Identities.

New York: Routledge.

Beltrán de Santa Rosa, Fray Pedro

1746 Arte de el Idioma Maya Reducido a Succintas Reglas, y Semilexicon Yucateco.Mex-

ico City. [John Carter Brown Library, Providence, rare book B746/B453a.]

Boyer, Richard

1995 Lives of the Bigamists: Marriage, Family, and Community in Colonial Mexico.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Bricker, Victoria Reifler

1981 The Indian Christ, the Indian King: The Historical Substrate of Maya Myth and Rit-

ual. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bricker, Victoria R., Eleuterio Po

ʔot Yah, and Ofelia Dzul de Poʔot

1998 A Dictionary of the Maya Language As Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. Salt Lake City:

University of Utah Press.

Brown, Denise F.

1993 “Yucatec Maya Settling, Settlement, and Spatiality.” PhD dissertation, University

of California, Riverside.

Cañizares Esguerra, Jorge

1999 “New World, New Stars: Patriotic Astrology and the Invention of Indian and Cre-

ole Bodies in Colonial Spanish America, 1600–1650,” i n American Historical

Review 104:1 (February), 33–68.

Cárdenas y Valencia, Br. Francisco de

1635 (manuscript date). Relación historial ecclesiastica de la provincia de Yucatán. British

Library, manuscript Eg. 1791.

Carmack, Robert, ed.

1988 Harvest of Violence: The Maya Indians and the Guatemalan Crisis. Norman: Uni-

versity of Oklahoma Press.

Castañeda, Quetzil

1996 In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Castro, Inés de

2001 “Die Geschichte der sogenannten Pacificos del Sur während des Kastenkrieges

von Yucatan: 1851–1895. Eine ethnohistorische Untersuchung,” PhD dissertation,

Maya Ethnogenesis 85

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 85

Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn.

Chuchiak, John F., IV

1997 “Intellectuals, Indians and the Press: The Polemical Journalism of Justo Sierra

O’Reilly,” in Saastun 0:2 (August), 2–50.

Ciudad Real, Fray Antonio de

N.d. [late-sixteenth-century manuscript]. Maya Motul Dictionary [original manuscript

untitled], 2 vols. John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Codex-Ind 8.

Clendinnen, Inga

1987 Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatan, 15 17–15 70. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Cline, Howard F

1947 “Regionalism and Society in Yucatan, 1825–1847: A Study of ‘Progressivism’ and

the Origins of the Caste War.” PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Comaroff, John and Jean Comaroff

1992 Ethnography and the Historical Imagination. Boulder: Westview Press.

Cope, R. Douglas

1994 The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City,

1660–1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Dumond, Don E.

1997 The Machete and the Cross: Campesino Rebellion in Yucatan. Lincoln: University

of Nebraska Press.

Edmonson, Munro S.

1982 The Ancient Future of the Itza: The Book of Chilam Balam of Tizimin. Austin: Uni-

versity of Texas Press.

1986 Heaven Born Merida and Its Destiny: The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel.

Austin: University of Texas Press.

Elliott, J. H.

1970 The Old World and the New, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press.

Fallaw, Ben

1997 “Cárdenas and the Caste War that wasn’t: State Power and Indigenismo in Post-

Revolutionary Yucatán,” in The Americas 53:4.

Fischer, Edward F.

2001 Cultural Logics and Global Economics: Maya Identity in Thought and Practice.

Austin: University of Texas Press.

Friedman, Jonathan

1992 “The Past in the Future: History and the Politics of Identity,” in American Anthro-

pologist 94:4, 837–59.

Gabbert, Wolfgang

2001 “On the Term ‘Maya’,” in Maya Survivalism, Ueli Hostettler and Matthew Restall,

eds. Markt Schwaben, Germany: Verlag Anton Saurwein, 25–34.

2004 Becoming Maya: Ethnicity and Social Inequality in Yucatan since 1500. Tucson,

University of Arizona Press

Gates, William

1931 “Review,” in Maya Society Quarterly 1:1 (December), 93–96.

86 The Journal of Lat i n American Anthropology

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 86

Gutiérrez, Natividad

1999 Nationalist Myths and Ethnic Identities: Indigenous Intellectuals and the Mexican

State. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Helms, Mary

1993 Craft and the Kingly Ideal: Art, Trade, and Power.Austin: University of Texas Press.

1994 “Essays on Objects: Interpretations of distance made tangible,” in Implicit Under-

standings, Stuart B. Schwartz, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

355–377.

1998 Access to Origins: Affines, Ancestors, and Aristocrats. Austin: University of Texas

Press.

Henige, David

1982 Oral Historiography. London: Longman.

Hervik, Peter

1999 Mayan People Within and Beyond Boundaries: Social Categories and Lived Identity

in Yucatán. Amsterdam: Harwood.

Hill, Robert M., II and John Monaghan

1987 Continuities in Highland Maya Social Organization: Ethnohistory in Sacapulas,

Guatemala. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hostettler, Ueli and Matthew Restall, eds.

2001 Maya Survivalism. Markt Schwaben, Germany: Verlag Anton Saurwein.

Jones, Grant D.

1998 The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Karttunen, Frances and James Lockhart

1987 The Art of Nahuatl Speech: The Bancroft Dialogues. Los Angeles: University of Cal-

ifornia, Los Angeles, Latin American Center.

Keen, Benjamin

1971 The Aztec Image in Western Thought. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Kellogg, Susan

2000 “Depicting Mestizaje: Gendered Images of Ethnorace in Colonial Mexican Texts,”

in Journal of Women’s History 12:3 (Autumn), 69–92.

Knight, Alan

1990 “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo: Mexico, 1910–1940,” i n The Idea of Race

in Latin America, 1870–1940, ed. Richard Graham. Austin: University of Texas

Press, 71–113.

Landa, fray Diego de

1959 Relación de las cosas de Yucatán [1566]. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa.

Lockhart, James

1992 The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lockhart, James and Stuart B. Schwartz

1983 Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil.Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mengin, Ernst ed.

1972 Bocabulario de Mayathan: Das Wörterbuch der Yukatekischen Mayasprache. Graz,

Austria: Akademische Druck.

Maya Ethnogenesis 87

04_Restall.qxd 3/1/04 3:40 PM Page 87

Montejo, Victor

1999 Voices from Exile: Violence and Survival in Modern Maya History. Norman: Uni-

versity of Oklahoma Press.

Patch, Robert W.

1991 “Decolonization, the Agrarian Problem, and the Origins of the Caste War,

1812–1847,” i n Land, Labor, and Capital in Modern Yucatán: Essays in Regional His-

tory and Political Economy, Jeffrey Brannon and Gilbert Joseph, eds. Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press, 51–81.

Pío Pérez, Juan

1898 Coordinación Alfabetica de las voces de la idioma maya que se hallan en el arte y

obras del padre Fr. Pedro Beltrán de Santa Rosa. Mérida, Yucatán: Imprenta de la

Ermita.

RHGY. Relaciones Histórico-Geográficas de la Gobernación de Yucatán [1579–81]. Mexico

City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2 vols., 1983.

Reed, Nelson

1964 The Caste War of Yucatan. Stanford: Stanford University Press. (Revised edition,

2001.)

Restall, Matthew

1997a The Maya World: Yucatec Culture and Society, 1550–1850. Stanford: Stanford Uni-

versity Press.

1997b “Heirs to the Hieroglyphs: Indigenous Writing in Colonial Mesoamerica,” in The

Americas 54:2 (October), 239–67.

1998a Maya Conquistador. Boston: Beacon Press.

1998b “The Ties That Bind: Social Cohesion and the Yucatec Maya Family,” in Journal

of Family History 23:4 (October), 355–81.

2001 “The People of the Patio: Ethnohistorical Evidence of Yucatec Maya Royal

Courts,” in Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya, Takeshi Inomata and Stephen

Houston, eds. Boulder: Westview Press, 355–90.

2003 Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. New York: Oxford University Press.

Restall, Matthew and John F. Chuchiak

2002 “A Reevaluation of the Authenticity of Fray Diego de Landa’s Relación de las cosas

de Yucatán,” i n Ethnohistory 49:3 (Summer), 651–69.

N.d. The Friar and the Maya: Fray Diego de Landa’s Relación de las cosas de Yucatán.

Unpublished manuscript.

Rothschild, Joseph

1981 Ethnopolitics: A Conceptual Framework. New York: Columbia University Press.