1

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH AT KARACHI

Present:

Mr. Justice Muhammad Shafi Siddiqui

Mr. Justice Jawad Akbar Sarwana

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.D-132 OF 2019

and 126 other connected petitions as per annexure “A”

M/s Millennium Mall Management Co.

Versus

Pakistan & others

Dates of Hearing:

17.10.2023, 24.10.2023, 25.10.2023, 30.10.2023,

01.11.2023, 06.11.2023, 10.11.2023, 13.11.2023,

15.11.2023, 20.11.2023, 21.11.2023, 28.11.2023,

04.12.2023, 13.12.2023, and 14.12.2023.

Date of Short Order:

14.12.2023

Date of Reasons

06.01.2024

Messrs. Ayan Mustafa Memon assisted by Ali Zuberi, Habibullah Masood,

Amna Khalil, Nawaz Khan and Shahreen Chugtai, (Khwaja Shamsul Islam

along with Imran Taj, Imtiaz Ali Shah & Khalil Awan, in C.P. No. D-

2603/2023), (Ms. Naheed A. Shahid & Daniyal Ellahi in C.P. No. D-

71/2022 & 848/2023), (Ali John, Altamash Arab, Advocate in C.P. No. D-

6819/2022), Abdul Wajid Wyne, (M. Rafi Kamboh, in C.P. No. D- 6396 &

6397 of 2020), Arif Khan, (M. Saad Siddiqui and Sahibzada Mubeen in

C.P. No. D- 840/2022, 5861/2021, 3246/2021, 2970/2020, 1494/2019),

Farhan Zia Abrar, (Zain A. Jatoi, Muhammad Mustafa Mumdani, Advocate

in C.P. No. D- 2521/2022), (Ghulam Haider Shaikh in C.P. No. D-

1251/2021), (Abid Hussain and Zahid Mehmood in C.P. No. D- 3170 &

3171 of 2021), (Fahad Arif Khilji in C.P. No. D- 3763 and 3764/2021),

Ahmed Mujtaba in C.P. No. D- 3803/2022, Naeem Suleman, Arshad

Hussain Shehzad, Waseem Farooq, Tauqir Randhawa, Kashan Ahmed,

(Mian Mushtaq Ahmed in C.P. No. D- 4306 to 4327 of 2017 and

3532/2018), Hanif Faisal Alam, (Hassan Khursheed Hashmi in C.P. No. D-

5521/2022), (Salman Mirza and Ahmed Magsi in C.P. No. D- 132/2019,

3135/2021 and 3359/2021), Abdul Qayoom Abbasi, Raja Muhammad

Safeer (Syed Maqbool Hussain Shah in C.P. No. D- 2797/2021, Syed

Noman Zahid Ali, Arsal Rahat Ali, (Mehmood Ali for IBA and Behzad

Haider in C.P. No. D- 5459/2022), (Ahmed Madni & Peer Ali in C.P. No.

D- 446 of 2023), (Ms.Sadia Sumera in C.P. No. D- 4184/2022), (Ahmed

Nizamani in C.P. No. D- 3246/2021), Dr. Rana Khan, (Rajesh Kumar in

C.P. No. D- 5673/2021), (Malik Khushhal Khan in C.P. No. D- 3987/2018

& 946/2022), Muhammad Naved, (Fazal Mehmood Sherwani in C.P. No.

D- 4159/2020), Masood Ali, Advocates for Petitioners.

Messrs. (Abdullah Munshi, Shajeeuddin Siddiqui and Imdad Ali Bhatti for

Clifton Cantonment Board in C.P. No. D-4985/2018, 5391/2018,

3426/2018, 5166/2018, 5167/2018, 6506/2020 & 1251/2021), (Farooq

Hamid Naek assisted by Syed Qaim A. Shah, G.Murtaza Bhanbhro and

Saad H. Ammar in C.P. No. D- 132/2019 and 1220/2023 for Respondent

No.2), Dr. Farogh Naseem, Ahmed Ali Hussain, S. Zaeem Hyder, Aman

Aftab, M. Aizaz Ahmed, Syed Shohrat Hussain Rizvi for Karachi

Cantonment Board, Aqib Hussain, (Afnan Saiduzzaman Siddiqui, Iftikhar

Hussain, Zohra Ahmed for CBC in C.P. No. D- 1228/2019, 1949/2019 &

946/2022), (Dr. Shahab Imam & Syeda Abida Bukhari for CBC in C.P. No.

2

D- 1220 and 2603/2023), Ashraf Ali Butt, Rehmatunnisa, Sohail H.K.

Rana, Ms.Huma F. Bhutto, Fahim Haider Moosvi, (Zain A. Soomro for

Respondent No.2 in C.P. No. D- 1661 and 249 of 2021), Akhtar Hussain

Shaikh, Syed M. Ghazen, Shahid Ahmed for KW&SC, K, A. Jahangir in

C.P. No. D- 3100/2023 for CBC, (Muhammad Aqeel Qureshi in C.P. No. D-

4606/2020), (Shahid Hussain Korejo in C.P. No. D- 6803/2022 for

respondent No.2), (Saqib Soomro and Ahmed Mujtaba in C.P. No. D-

6806/2022 for respondent No.2), (Ameer Ali Soomro in C.P. No. D-

6805/2022 for respondent No.2), (Asif Amin for Respondent No.2 in C.P.

No. D- 1333/2021), Fozia M.Murad for Respondent in C.P. No. D-

132/2019, 3023, 3669, 7318, 7460 of 2015, (Mr.Talha Abbasi for DHA in

C.P. No. D- 4985/2018), Advocates for Respondents.

M/s. Zeeshan Adhi Addl.AG, Saifullah and Sandeep Molani, Asst.AG

Qazi Abdul Hameed Siddiqui, DAG, Khaleeq Ahmed DAG, Malik Sadaqat

Khan Addl. Attorney General and Qazi Ayazuddin, Asst. Attorney General

********

J U D G M E N T

Muhammad Shafi Siddiqui, J.- The subject matter of these petitions is

Tax demand based on annual rental value of property by different

Cantonment Boards from the petitioners. The petitioners’ assertion is

that it is a kind of tax and levy that taxes remain with the provinces only

whereas the federal government and the cantonment boards claim such

levy to be in their competence. In support of such questions raised, both

sides counsel have assisted us and summarized their structural points as

under:-

COUNSELS’ BULLET POINT SUBMISSIONS

MR. AYAN MUSTAFA MEMON

Mr. Ayan Mustafa Memon, learned counsel for petitioner in C.P. No. D-

2603/2023) has made the following submissions:

Post-18

th

Amendment, the subject of levying property tax rests with

the Provinces. Placed reliance on Entry No.50 of the Fourth Schedule

of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973.

Contended that after omission of the Seventh Schedule of the

Constitution, which was protected for a period by the Presidential

Order of 1979, levying of all property tax now rested with the

Provincial Government.

3

Argued that property tax had always been a provincial subject.

Contended that Entry 2 of the Fourth Schedule relied upon by the

petitioners was not a tax entry.

Argued that after the 18th Amendment, with regard to tax entries,

there was no provision for concurrent taxation. Placed reliance on

PLD 1975 SC 37, PLD 1978 Karachi 500 and PLD 2022 Peshawar 46.

Submitted that omission of 79 Order via P.O would not create any

vacuum on account of the Sindh Urban Immovable Property Tax Act,

1958 via 18

th

Amendment to Constitution.

Additionally, argued that any statute not in consonance with the

Constitution of Pakistan is invalid and be held accordingly. Pleaded

that Respondents’ reliance on the Cantonment Act, 1924 was

misconceived. Relied on PLD 1989 SC 416.

Contended that the above case law had been followed and approved,

cited by the Supreme Court in 1993 SCMR 1523.

Further contended that as per the Benazir Bhutto case, the referred

principles had been further expanded. Relied on pages 1528 page

1530 of the Benazir Bhutto case.

Concluded that the Provinces had domain over property tax, and not

the federal government, and relied on Freight Forwarder’s case (2017

PTD 1).

Relied heavily on the interpretation of Article 270A of Constitution of

Islamic Republic of Pakistan in terms of Benazir’s case.

MR. KHAWAJA SHAMSUL ISLAM, Learned Counsel For Petitioner in C.P.

NO. D- 2603/2023).

Mr. Khawaja Shamsul Islam was asked to address only those points

which are not covered by other counsel to save the time. He then

took us to the history of cantonment and their formation. It is

claimed that these cantonment boards are essentially civil/housing

societies and cannot be identified as cantonments.

He claimed that under the garb of Cantonment board, the authority

under the act are trespassing provincial land and federal land

4

abutting seashore and the geographical extension is not permissible

in such way.

Additionally he took us to the impugned notification in his petition

which unilaterally enhanced the assessment to many folds thus

rendering the mechanism of Section-60 to 64 of Cantonment Act as

redundant.

It is claimed that person issuing the said notification is not identified

by Cantonment Act, 1924. He objected to the creation of new

cantonment after urbanization and notification in this regard by

Federal Government.

MR. ZEESHAN ADHI, LEARNED ADDITIONAL ADVOCATE GENERAL, SINDH

Argued that property tax had always been a provincial subject. To

illustrate this he took us through the several laws, starting from the

Government Act of India of 1935, 1956 Constitution, the Constitution

of 1962 and the Constitution of 1973.

He argued that any statute not in consonance with the Constitution

of Pakistan is invalid. Pleaded that Respondents’ reliance on the

Cantonment Act, 1924 was misconceived and also relied upon PLD

1989 SC 416 (relevant page 509 placitum AA, page 511, both

paragraphs and 512 second paragraph).

Contended that the above case law had been approved by the

Supreme Court in 1993 SCMR 1523.

Concluded that the Provinces had domain over property tax, and not

the federal government.

Also relied upon Benazir’s case as far as application of Article 270A

is concerned.

MR. ABDULLAH MUNSHI, learned counsel for Respondent/Clifton

Cantonment Board (CP No.D-4985/2018, CP No.D-5166/2018, C.P No.D-

5167/2018).

Commenced submissions with the history of the cantonments in the

Indian Subcontinent – pre-partition till present. Provided a backdrop

of how the Cantonments came about in the Indian Subcontinent,

starting from the Cantonment Act of 1864, Cantonment Codes of

5

1899, 1912 and finally, the Cantonments Act of 1924, which

regulated the municipal functions of the Cantonment Boards.

Argued that there was nothing in the Cantonments Act, 1924, which

violated Articles 8 and 25 of the Constitution of Pakistan. Relied on

I.A. Sharwani and Others v, Government of Pakistan through

Secretary, Finance Division, Islamabad and Others, 1991 SCMR 1041

and Lucky Cement Ltd. v. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa through Secretary

Local Government and Rural Development, Peshawar, 2022 SCMR

1994.

Further, argued that if there was/is a difference of opinion with

regard to the powers under Cantonments Act, 1924, between the

Federal Government and the Provincial Governments, Article 184 of

the Constitution of Pakistan should intervened. The private

petitioners challenging the constitutionality of the federal

government's powers under Article 199 of the Constitution of Pakistan

were/are acting contrary to Article 184.

Contended that in case of an action initiated by any of the Provincial

Governments without adopting the procedure highlighted under the

Articles of the Constitution of Pakistan, such matter is to be agitated

before the Supreme Court of Pakistan only and not the High Courts.

He relied on Haider Mukhtar and Others v. Government of Punjab

and Others, PLD 2014 Lahore 214, and Khalid Mahmood and Others v.

Federation of Pakistan through Secretary, Ministry of Finance,

Islamabad and 74 Others, PLD 2003 Lahore 629.

As a corollary argued that the Petitions filed before us are malafide

and he relied on The Federation of Pakistan through the Secretary,

Establishment Division, Government of Pakistan, Rawalpindi v. Saeed

Ahmad Khan and Others, PLD 1974 SC 152.

Further contended that under Article 270-A of the Constitution of

Pakistan, the laws promulgated under the Seventh Schedule (Article

270-A (6)) were saved. The Seventy Schedule included the

Cantonments (Urban Immovables Property and Entertainment Duty)

Order 1979, which would remain in place. Contended that after

Article 270-A, when the Eighth Amendment ratified the said

provision, the Presidential Order, which included Cantonment's power

6

to tax, was protected and could not be assailed until and unless the

Parliament enacted fresh legislation on the same subject.

Additionally, argued that none of the Petitioners had challenged the

validity of the Presidential Orders which continued to remain in

place. He relied on the Federation of Pakistan and Another v.

Ghulam Mustafa Khar, PLD 1989 SC 26, Mehmood Khan Achakzai and

Others, v. Federation of Pakistan and Others, PLD 1997 SC 426, and

Sargodha Textile Mills v. Federation of Pakistan through Secretary

Ministry of Defence, Rawalpindi and 3 Others, PLD 2004 SC 743.

Further submitted that section 14 of the Sindh Local Government

Act, 2013, specifically excluded “Cantonments” and tax on annual

rental value was also excluded under Schedule “V” of the said Act.

Submitted that the Cantonments had the power to charge property

tax and placed reliance on Pakistan v. Province of Punjab and

Others, PLD 1975 SC 37, PLD 2022 Peshawar 46.

Further submitted that for all practical purposes, the Government of

Sindh has conceded that they will not administer the collection of tax

on cantonment lands. To this end, he argued that in fact, by applying

“de facto” doctrine, Cantonment had the powers to levy and collect

tax impugned in the Petitions.

Argued that the Cantonments were local municipal governments and

Entry 2 of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution of Pakistan would

become redundant if the power to tax is taken away. Cantonment

would be unable to render services.

Lastly argued that if the Court concludes that there is no competency

for Cantonments to levy tax, then equally, there is no legislation on

the part of province to impose such tax. The Cantonments Act, 1924,

has not been repealed after the 18th Amendment, and Cantonments

being a strategic area require preservation, which can only be

achieved by way of tax.

MR. FAROOQ HAMID NAEK

Mr. Farooq Naek, who was engaged subsequently, while cases were

being heard, appeared for Faisal Cantonment Board. and argued in line

with Mr. Munshi's arguments and raised the following additional grounds:

7

At the outset, Mr. Naek contended that Entry No.50 of the Fourth

Schedule specifically referred to “taxes on immovable property” and

no other genre of tax involved i.e tax on rented value of immovable

property.

Argued that taxes on immovable property were/are of four kinds

classified as:

a) Capital value tax on assets;

b) Capital gain tax on property;

c) Income tax on property; and

d) Annual rental value.

With regard to (a) Capital Value Tax on Assets, Mr. Naek referred to

Section 4 of the Sindh Finance Act, 2010. He claimed that the capital

value tax was payable by the owners of the property whereas capital

gain is payable on sale of property. Next, he took the Court to

Section 15 of Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 and contended that

income tax from property income, triggered under Income Tax

Ordinance, 2001 does not deal with value of property and it is in

relation to rent received hence it was a tax on rent being collected

on the rental income only and precisely includes the tax on annual

rental value also.

Contended that all these three categories of tax were not covered by

Entry No.50 of the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution of Pakistan.

Contended that the entry mentioned in Fourth Schedule did not

expressly refer to annual rental value and that all entries were silent

with regard to annual rental value.

In the circumstances, he argued that Entry No.2 was relevant to the

case at hand. He argued that Entry 2 has empowered the

Cantonment/federal government to impose tax.

He also argued the applicability of Article 7 to be read with entry 54

and Article 2 of Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

BARRISTER DR. FAROGH NASEEM for Cantonment Board.

Barrister Farogh Naseem argued that the tax being collected by

Cantonments was, although being referred to as a tax, it was, in

fact, not a tax. Therefore, argued that because it is not a tax, it

8

does not fall squarely within the tax entries in the Fourth

Schedule of the Constitution relating to tax i.e, 43 to 53.

Argued that the tax imposed by Cantonments was “something

else” but not a tax. He relied upon the Workers Welfare Fund and

GIDC cases to support his contention. The crux of his argument

was that the “revenue” collected by the cantonment is for

cantonment fund for a purpose and its place either in

consolidated fund of Federation or province is not going to alter

the status of revenue collected as “sums” for cantonment fund

and not being tax.

Argued that whatever was/is being collected goes to the

Cantonment fund under section 106 for its application under

section 109.

He argued that if the collection by Cantonment was not a tax,

then it was covered by entry 54 as a “Fee”. Thus, if it is, then

Entries 54 and 2 would regulate the recovery of cantonment tax,

which was/is a tax by name only. He argued that the taxing power

is given under the Fourth Schedule between Entry 43 to 53 and

that the collection by the Cantonments is not in the nature of a

tax but closer to a fee in terms of its utility and application.

Further submitted that the amount collected is used as an

expenditure, and on this count too it is not a tax regardless of

whatever name is used to describe it.

Article 142 and Article 7 of the Constitution disclosed separate

entities and Article 142 cannot be read in isolation.

Seventh Schedule may not be available but the listed laws are still

in force. Any item in Seventy Schedule is subject to amendment

by simple majority.

Article 279 – the laws listed in Seventh Schedule have not been

replaced by appropriate legislation.

Cantonment Boards are transprovincial – hence federal subject.

9

ATTORNEY-GENERAL/DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL QAZI ABDUL HAMEED

SIDDIQUI

Notices under Section 27A CPC were served and DAG addressed the

Court.

Adopted arguments of Dr. Farogh Naseem.

Argue that Provincial Government is “sleeping on its right.”

In CP D-2149, page 27, Government of Sindh has stated that they

wish to claim tax on annual rental value but if this is so, then the

Provincial Government must proceed to the Supreme Court.

2. Heard counsels and perused record.

3. For the sake of brevity, in response to some common arguments,

the cumulative and required reasons are provided, whereas individual

points raised have been responded to separately in the later part of

judgment.

4. The primary object of concern in understanding the subject, i.e.

tax on immovable property, is the legislative competence as restored by

the restoration of the constitution via 14th Presidential Order 1985,

followed by the 18th Amendment to the Constitution of the Islamic

Republic of Pakistan, 1973. In order to understand its effect with clarity,

a brief history of such legislative competence on the subject is needed.

5. Tax on immovable property has always been a provincial subject.

If we trace history since 1935, i.e. from the date of promulgation of the

Government of India Act, 1935 passed by the British Parliament, which

received royal assent in August 1935, we understand that the subject

always remained part of the provincial pool.

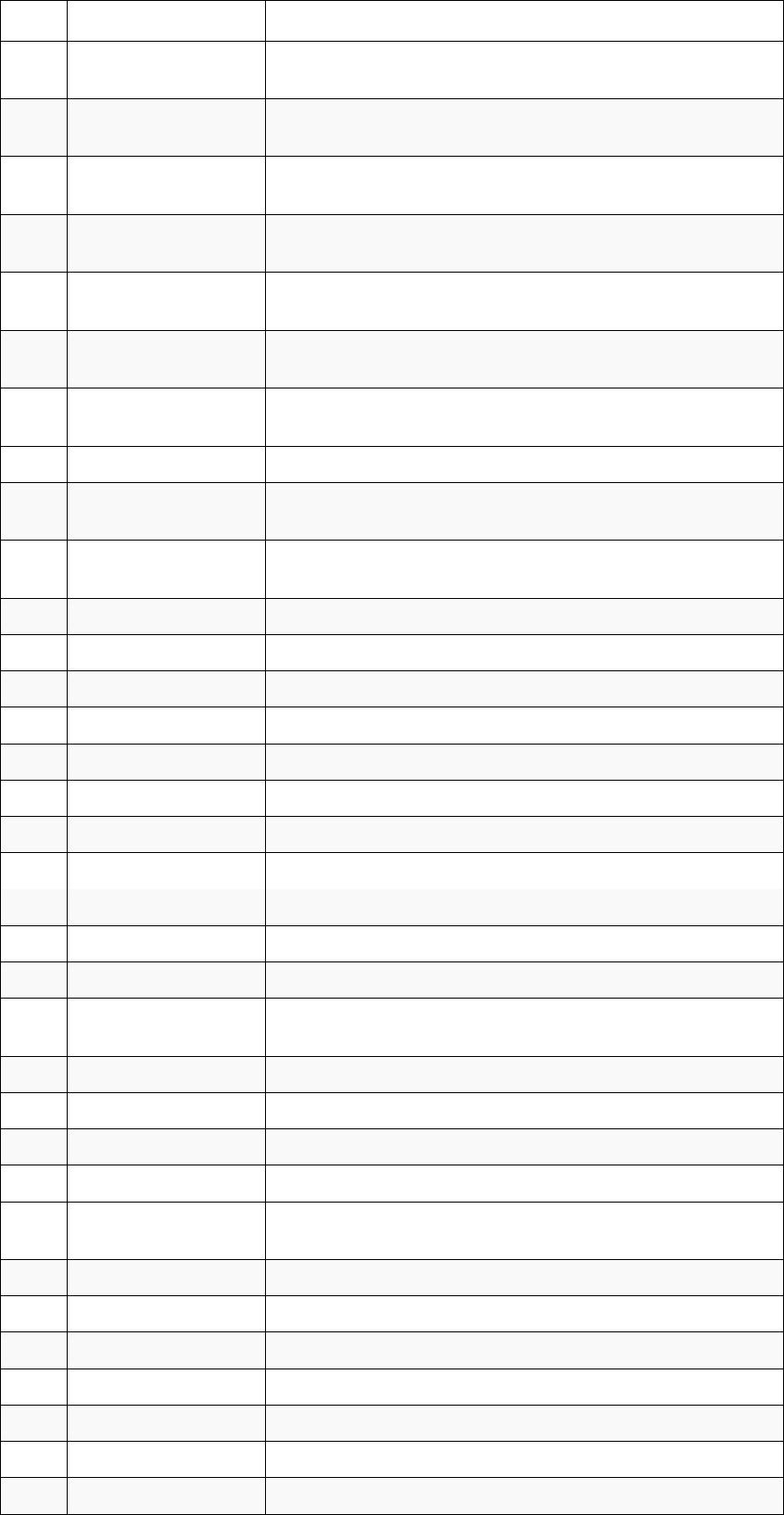

6. A comparative table of taxes on land and buildings is given

below:-

10

S.No.

Constitution of

Pakistan/India

Act

Entry No.

Subject of Tax

1.

1935

Entry No.42 of

Provincial List

Taxes on land and

buildings, hearths and

windows

2.

1956

Entry No.70 of

Provincial List

Taxes on lands and

buildings

3.

1962

No Entry in Third

Schedule

No Entry in the list of

Central Legislature i.e.

Third Schedule under

Article 132

4

1972 (Interim

Constitution)

Entry 40 of

Provincial List

Taxes on land and

buildings ………………………

5.

1973 (Before 18

th

Amendment)

No Entry in FLL and

CLL

No Entry in FLL and CLL

6.

1973 (after 18

th

Amendment)

No Entry in FLL

(CLL omitted)

No entry in FLL (CLL

omitted)

7. Last horizontal column provides only the Federal Legislative List

(FLL) whereas the Concurrent Legislative List (CLL) omitted and the

subject was not available in the FLL, whereas second last horizontal

column shows both FLL and CLL but the subject is not available.

8. The other constitutional history is of taxes on the capital value of

the assets (covered by its limb of entry 50) and the table is as under:-

S.No.

Constitution of

Pakistan/India

Act

Entry No.

Gist of Entry

1.

1935

Entry No.55 of

Federal List

Taxes on capital value

of the assets, exclusive

of agricultural land of

individual and

companies; taxes on the

capital of companies

2.

1956

Entry No.25 of

Federal List

Duties of customs

(including export

duties), duties of excise

(including duties on salt,

but excluding alcoholic

liquor, opium and other

narcotics), Corporation

taxes and taxes on

income other than

agricultural income;

estate and succession

duties in respect of

11

property other than

agricultural land; (taxes

on capital value of

assets exclusive of

agricultural land; taxes

on sales and purchases;

stamp duties on

negotiable instruments

and insurance policies;

terminal taxes on goods

or passengers carried by

railway, sea or air; taxes

on their fares and

freights; taxes on

mineral oil and natural

gas. (underlining is for

emphasis.

3.

1962

Entry No.42(e) of

Central List

Taxes on capital value

of assets not including

taxes on capital gains on

immovable property.

4

1972 (Interim

Constitution)

Entry 57 of Federal

List

Taxes on capital value

of assets, not including

taxes on capital gains on

immovable property.

5.

1973 (Before 18

th

Amendment)

Entry No.50 of

Federal List

Taxes on capital value

of the assets, not

including taxes on

capital gains on

immovable property.

6.

1973 (after 18

th

Amendment)

Entry 50 of Federal

List

Taxes on the capital

value of the assets, not

including taxes on

immovable property.

9. The constitutional history of the later subject, i.e. “taxes on the

capital value of assets,” shows that this subject always remained within

the domain of the Federal Legislature, as against taxes on the

immovable property.

10. After examining the above history, it becomes clear that the

subjects of “taxes on land and buildings” and “taxes on the capital value

of the assets” are separate subjects/entries; the prior one primarily

belongs to the provincial legislature, and the later subject belongs to

the federal legislature, historically.

12

11. As of now, after the 18th Amendment, the Federal Legislature is

not constitutionally empowered to levy, impose, charge and/or recover

(directly or indirectly) any tax on immovable property, including a tax

on the annual rental value of immovable property within a province,

under a law legislated by Federation.

12. For a brief period, the subject identified above, i.e. tax on the

immovable property, came into the basket of the federation during the

Marshal Law period, and a brief history is required to understand such

“reroute” of the legislature.

13. In 1958 (per constitution 1956), the provincial government

enacted the law called West Pakistan Urban Immovable Property Tax

Act, 1958, and the subject tax on land and buildings continued to vest in

the province since the promulgation of the India Act, 1935.

14. This core issue of charge, levy and recovery of such taxes,

identified above, came for consideration before Courts earlier when the

cantonments intervened and consequently the issue decided by the

Supreme Court of Pakistan in the case of Pakistan through Ministry of

Defence v. Province of Punjab

1

. The Supreme Court clarified that since

the cantonment areas are located within the respective provinces, they

were/are, therefore, part of the provinces and do not constitute a

federal territory. The Supreme Court summed up that tax on immovable

properties is a subject to be dealt with by the provincial statute of 1958

in cantonment areas in consonance with the 1956 constitution.

15. This judgment was then followed particularly in the case of

Gulzar Cinema

2

.

1

Pakistan through Ministry of Defence v. Province of Punjab (PLD 1975 SC 37)

2

M/s Gulzar Cinema v. Government of Pakistan (PLD 1978 Karachi 500)

13

16. The two judgments provide that imposition of tax, i.e. levy of

property tax by the provincial government in areas lying within the

limits of the cantonment board, is valid.

17. Now comes the period when martial law was imposed in Pakistan

and Chief Martial Law Administrator acting as President of Pakistan,

finding it as an alternate way, promulgated the “Cantonments (Urban

Immovable Property Tax and Entertainment Duty) Order, 1979”

commonly called Presidential Order 13 of 1979. This is based on 5

sections only, and purposely, by virtue of section 3, the effects of the

Act of 1958 ibid ceased on properties within the cantonment areas, and

the said order of 1979 was then applied to such properties.

18. Mr. Munshi emphasised that notwithstanding the 18

th

Amendment

and revival of the constitution in 1985, the subject law of 1979 is in line

with the Cantonment Act, 1924 read with Presidential Order 13 of 1979

and that cantonments are competent to levy and collect such taxes as

the scheme of such statutes are not overshadowed either by restoration

of constitution or assumption of a constitutional frame after 18

th

Amendment.

19. Per section 3 of the Presidential Order No.13 of 1979 the

operation of The Urban Immovable Property Tax Act, 1958 was ceased to

be given effect in the cantonment areas available in the provinces,

apparently, to circumvent the two judgments of Supreme Court of 1975

and 1978, referred above; it was legislated that the cantonments could

impose taxes to be assessed on the annual rental value of the building

and lands as per provisions of Cantonment Act, 1924. The Said Order of

1979 was then given effect for a brief period as identified in the 8

th

Amendment to the Constitution of 1973 when it was introduced. The

Presidential Order No.13 of 1979, amongst other Orders, laws etc. were

14

given protection (for a specified period), in terms of amendment in the

Constitution, which is being identified as Article 270A and the 7

th

Schedule to the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 where

the Cantonments (Urban Immovable Property Tax and Entertainment

Duty) Order, 1979 was placed and protected which then lost its

effectiveness after the revival of constitution and 18

th

Amendment to

the Constitution.

20. A reading of Article 270A as a whole provides that the protection

was given to two types of laws: (a) those which were mentioned by

reference to their date of promulgation in Article 270A and (b) those

which were specifically mentioned in 7

th

Schedule. This particular Order,

which now seems to be overlapping and transgressing the constitutional

mandate and provincial law of 1958 after the restoration of the

constitution and enactment of 18

th

Amendment, is mentioned in the 7

th

Schedule, now omitted.

21. Sub-clause 1 of Act 270A clarified the period of effectiveness of

the law made available between July 1977 to 30th December 1985, i.e.

when Article 270A was introduced in the constitution. Sub-clause 2 of

Article 270A saved all actions orders, proceedings by any authority/any

person “again clarifying” between July, 1977 to the date of Article

270(A). Sub-clause 3 emphasised that such Orders, Ordinances,

Regulations, Martial Law Orders, Enactments, Notifications and Rules

etc, which were in force immediately before the date of Article 270A

shall continue until repealed, amended or altered by the competent

authority, whereas sub-clause 6 requires clause 1 amendment by the

appropriate legislature.

22. Article 270A of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of

Pakistan, 1973 and its effect came for consideration and interpretation

15

before the Supreme Court in the case of Benazir Bhutto

3

. Although the

subject matter in the said judgment of the Supreme Court is to the

extent of certain amendments which were made through Presidential

Orders to the Political Parties Act in the year 1978-1979, during the

period of Martial Law governing the country, however, the subject

amendments were challenged (as are in this case in one of the petitions

as far as 1979’s Order is concerned) as it claimed to have been protected

by Article 270A (as cantonments claimed now for 1979 Order), which

amendments (under the Political Parties Act) deprived the citizens of

one of their fundamental rights. The judgment distinguished the effect

of the law promulgated during the period in two categories, i.e. (i) those

laws that are protected by Article 270A as they fell within the time zone

specifically mentioned therein and (ii) those laws that were specifically

protected under the 7

th

Schedule. The said amendments in the Political

Parties Act fell within the first category, referred above, and the

Supreme Court held that future operation of all laws protected under

Article 270A would be “subject to limitations contained in the

Constitution” (emphasis applied), which include that not only can such

laws be struck down for violation of fundamental rights, as enshrined in

the Constitution, but also on the touchstone of constitutional

competence i.e. no such laws could be deemed to have been valid, after

the period, as identified, against constitutional mandate and frame, as it

exist and existed on the day of restoration of Constitution and/or 18

th

Amendment, whatever the case may be.

23. The Hon'ble Mr. Justice Muhammad Haleem, Chief Justice of

Pakistan (as he then was), extended the reasoning for the conclusion

drawn by the Bench in the aforesaid Benazir case as under:-

The most important legal instrument which follows

hereafter is the Revival of the Constitution of 1973 Order,

3

PLD 1988 SC 416 (Benazir Bhutto v. Federation of Pakistan)

16

1985 (P.0.14 of 1985), which was promulgated on 2nd of

March, 1985. Although this Order came into force at once

but by Article 4, its revival was deferred to such dates on

which the President was authorised, by notification, to

revive its different provisions. Again by Article 5 of this

Order, the President was authorised to make such

provisions and pass such orders in case any difficulty arose

in giving effect to any of the provisions of this Order.

However, by Article 2 of this Order extensive amendments

were made in the 1973 Constitution, including the

insertion of Article 270-A. By notification issued under

Article 4 of the Order on 10th of March, 1985, provisions

other than Articles 6, 8 to 28, clauses (2) and 2(A) of

Article 101, Articles 199, 213 to 216 and 270-A were

revived. By Constitution (Second Amendment) Order, 1985

(P.0.20 of 1985), promulgated on 17-3-1985, amongst

certain other amendments clause (6) of Article 270-A was

substituted for the following: "(6) The President's Orders

referred to in clause (1) shall not be altered, repealed or

amended without the previous sanction of the President."

The earlier text of this clause was: "Any of the President's

Orders referred to in clause (1) may be amended in the

manner provided for amendment of the Constitution." On

the 19th of March, 1985, Constitution (Third Amendment)

Order, 1985 (President's Order 24 of 1985) was

promulgated. Thereafter on 11th of November, 1985,

Constitution (Eighth Amendment) Act, 1985, was

promulgated which came into force at once except section

19 which was to take effect on the date on which the

Proclamation of the fifth day of July, 1977, was revoked.

This Article related to the substitution of Article 270-A of

the Constitution as enacted by the Majlis-e-Shoora for that

earlier inserted by the President in the Revival of the

Constitution of 1973 Order, 1985 (President's Order 14 of

1985) and a new Schedule called the Seventh Schedule was

added by section 20……….

………………………

The constitutional validity given by Article 270-A(1) is

retrospective as it achieves to give validity to laws enacted

between a specified period. This validity is, therefore, of a

pattern of a curative or validating statute and must be

understood and be operative in that context. In Black's Law

Dictionary, Fifth Edn., p.1390, validating statute is stated

to be: "A statute, purpose of which is to cure past errors

and omissions and thus make valid what was invalid, but it

grants no indulgence for the correction of future errors".

In Pandit Ram Parkash v. Smt. Savitri Devi (A I R 1958

Punjab 87), it was held that curative and validating

statutes operate on conditions already existing and can

have no prospective operation." In Moti Ram v. Bakhwant

Singh (A I R 1968 Punjab and Haryana 141), it was held: "A

curative act is a statute passed to cure defect in a prior

law and has prospective operation". In Sutherland on

Statutory Construction, Vo1.II, 3rd Edn., p.243. it is

stated: "Retroactive operation will more readily be

ascribed to legislation that is curative or legalising than to

legislation which may be disadvantageously though legally,

(Emphasis applied)

17

affect past relations and transactions". In Amalgamated

Coalfields, Calcutta v. State (A I R 1967 M.P. 56), it was

held:

"An invalid Act can be validated by subsequent

statute of the competent legislative authority, if

the validating statute authorises the doing of the

act at the time when it was done. In the absence of

such authorisation, the validation will be futile as

that will only amount to an attempt to exercise a

power ex hypothesis, which does not exist."

Having regard to the purpose of validation, the defects in

the legal measures when enacted during the specified

dates had to be cured in the state of things as they existed

which, of course, did not include any violation of a

constitutional norm; and validity in this context could not

be said to have achieved anything more than this. This is

not all.

The learned Attorney-General relied on the

non obstante expression "notwithstanding anything

contained in the Constitution" to extend the validity to the

covering of the violations of constitutional norms. This

expression only occurs in Article 270-A(1), which I have

already held to be referable to the ouster of the

jurisdiction of the Court. It has not been used in

sub-Article (3) nor can it be read into it as this would

amount to re-writing the Constitution which is not the

purport of interpretation. If the Legislature itself did not

consider it appropriate to give protection to the existing

laws against violations of Fundamental Rights then this

cannot be achieved by taking aid of this expression from

Article 270-A(1). This legislative intention is clear from

the progress of the Bill of the Constitution (Eighth

Amendment) Act, 1985 Bill (N.A. Bill No.13 of 1985) in the

National Assembly until it become an Act of the

Legislature:

…………………….

The language of this Order and that of para. 9 of

President's Order No.26 of 1962 and para.7 of President's

Order No.14 of 1972 is in pari materia. In his view, the

words "the provisions of this Order shall have effect"

meant that in spite of the repeal of Martial Law

Regulations and Martial Law Orders, they continued to

operate in future on being validated by Article 270-A(1). In

other words they survived the repeal and were continued

as laws under sub-Article (3) of the 1973 Constitution. This

contention hits at the proviso to Article 270-A(1) which

limits the power of the President and the Chief Martial

Law Administrator to make only such Martial Law

Regulations and Martial Law Orders after the thirtieth day

of September, 1985, which would facilitate or were

incidental to the revocation of the Proclamation of the

fifth day of July, 1977. Therefore, the Legislature only

gave validity to this extent and if they were to survive and

operate as Martial Law Regulations and Martial Law Orders

(Emphasis applied)

18

it would be against the purpose of legislation for in that

event it would entrench the Martial Law rather than to

facilitate the revocation of the proclamation of the

Martial Law. There is also the further reason that if the

Martial Law Regulations and Martial Law Orders were to

survive then they would be in conflict with some of the

paragraphs of this Order and in particular paragraph 5

which could not be the intention of the maker.

In my view, in the expression "the provisions of this Order

shall have effect", the key words are "shall have effect",

which mean: "shall have legal effect." (See

Venkataramaiya's Law Lexicon, Second Ed., Volume 3, p

.2217) . The purport of using these words is to give legal

protection to the several provisions of the Order as a

result of the change-over from Martial Law to rule of law

under the Constitution. This device was earlier adopted

for the same purpose so as not to leave a vacuum.

Accordingly, this submission of the learned

Attorney-General is untenable.

Another Member of the Bench Mr. Justice Nasim Hasan Shah expressed

himself as under:-

According to the learned Attorney-General, the effect of

sub-Article (1) of Article 270-A is that not only are the

laws made during the period 5th July, 1977 to 30th

December, 1985 alongwith their contents deemed to have

been competently made and enacted but also that the

jurisdiction of all Courts has been taken away to question

the validity of the said laws on any ground "whatsoever".

This blanket validation and complete immunity, to any

scrutiny thereof is further reinforced by the provisions of

sub-Article (3) of Article 270-A, which saves their future

operation and renders them immune from scrutiny in the

like manner.

On the other hand, according to Mr. Yahya Bakhtiar what

has been saved from all challenge by the provisions of Act

270-A is the entertainment of any plea to the effect that

the laws made during this period were not made by a

competent authority and the liability to be struck down on

that ground. In any case, the jurisdiction of the Courts to

see whether such a law, in its future continuance,

constitutes a violation of any of the Fundamental Rights,

which have now been restored is not ousted.

While considering the scope and effect of the provisions of

Article 270-A it is not without interest to refer to the

background and history of the enactment of this important

provision. It will be recalled that this provision was inserted

into the 1973-Constitution by the Constitution (Eighth

Amendment) Act, 1985 which was passed into law on l1th

November, 1985.

……………………………

19

On a careful consideration of the various provisions of

Articles 270-A I have reached the conclusion that none of

them has the effect of giving immunity to all the laws

made between 5th June, 1977 to 30th December, 1985,

from being tested on the touchstone of the inconsistency

with the Fundamental Rights. Full reasons for this views

have been given by my Lord the Chief Justice with which I

respectfully agree. This interpretation moreover gets

support from the history of the legislation noticed above.

The next Member of the Bench Mr. Justice Shafiur Rahman framed

questions, and the significant one being at serial No.2 is as under:-

(2) The affirmance, the adoption, the declaration and the

validation of laws specified in Article 270-A(1) of the

Constitution coupled with the clause ousting sweepingly the

jurisdiction of all the Courts has not the effect of either

effacing, eclipsing or of subordinating the Fundamental

Rights guaranteed by the Constitution to the citizens of the

country.

The next Member Mr. Justice Zaffar Hussain Mirza in relation to

the question arising out of the matter before him, expressed as under:-

Even otherwise the extreme position taken by the learned

Attorney-General does not stand the test of scrutiny if the

consequences flowing therefrom are taken into account. In

the first place it may be pointed out that clause (3) of the

Article in question seeks to continue in force not only the

existing laws but also notifications, rules, orders or

bye-laws. Accepting the argument that the words

"notwithstanding anything contained in the Constitution"

would also govern clause (3), would result in giving the

overriding effect to such notifications, rules, orders, or

bye-laws as against the Fundamental Rights. This in my

opinion could not be the intention of the legislature.

Secondly clause (3) covers not only the legislative

measures adopted during the Martial Law period as

specified in clause (1), but even pre-existing laws and

there appears no rational basis for imputing to the

legislature the intention to continue such pre-existing laws

free from all constitutional limitations in the future. It is,

therefore, clear that the non obstante clause under

consideration does not control clause (3) of Article 270-A.

Apparently the object underlying clause (3), as in case of

similar provisions in the earlier Constitutional

instruments, was to maintain the continuity of laws and to

prevent interruption in the legal force of the existing laws

so that legal rights are not affected by the disappearance

of the laws under which the rights and obligations accrued

or were incurred. It may be pointed out again that clause

(3) embraces all the existing laws including enactments

which were in force at the relevant time. Such enactments

and laws included some of the laws which were in

existence at the time of the enactment of Article 268(1) or

(Emphasis applied)

20

even earlier. Therefore, it will be unreasonable to

attribute to the legislature an intention to convert an

existing law which was to continue in force subject to the

Constitution, into a law which would override the

Constitutional limitations, after being continued under

Article 270-A. I find no good reason for adopting such a

construction. (Emphasis applied).

This conclusion is further reinforced by another

consideration. It will be observed that clause (3) of Article

270-A has the effect of continuing in force all the existing

laws that were in force immediately before the date on

which the proclamation of withdrawal of Martial Law was

issued and all the provisions of the Constitution were

revived. Accepting the argument of the learned

Attorney-General will mean that all the existing laws en

masse would achieve supra-Constitutional status free from

every constitutional limitation or constraint. Such

unbridled supremacy would mean the virtual continuation

of the entire legal order existing on the date of

withdrawal of Martial Law, over and above the

Constitution which, in consonance with the settled

principles of interpretation, is difficult to attribute to the

legislature.(Emphasis applied).

24. In Benazir Bhutto case the Hon’ble Bench members have agreed

that the future operation of laws protected under Article 270A would be

subject to the limitations contained in the Constitution, which include

that not only can such laws be struck down for violation of fundamental

rights recognised by the Constitution but also on the touchstone of

legislative competence identified in the Constitution. This view, as

authored by Mr. Justice Zaffar Hussain Mirza, was agreed by other

Members of the Bench as followed, such as Mr. Justice Abdul Kadir

Shaikh, Mr. Justice Javid Iqbal, Mr. Justice Saad Saood Jan, Mr. Justice

Hussain Qazilbash and Mr. Justice Usman Ali Shah.

25. Somehow, a similar view was taken by the Federal Shariat Court

wherein Presidential Orders’ protection vide Article 270A ousted the

jurisdiction of the Federal Shariat Court in the FATA territory. A

challenge to the Presidential Order was made not only on the basis of

fundamental rights’ infringement but also that the said Order was

“violative of Constitutional frame”, as restored when Marshall Law was

(Emphasis applied)

(Emphasis applied)

21

lifted. In terms of paragraph 19 and 21 of the judgment in the case of

Sajjad Hussain case

4

, the Federal Shariat Court has relied upon the

judgment of Benazir Bhutto to rule that the effect of laws protected

under Article 270A cannot travel beyond the line that was drawn by

Article 270A itself i.e. when it came into force and concluded its

effectiveness could be equated as sunrise and sunset. Article 270A itself

does not sanction the infinite applicability or continuity of the legal

instrument beyond the date when the legislative pillars

(assemblies/senate, etc.), through the restoration of the Constitution,

resurrected and started functioning. Thus, the law developed by the

Federal Shariat Court, as well as by the Supreme Court, was that the law

that was enacted in a period where the Constitution was in abeyance

cannot be given a sanction beyond the date when it was said to have

been protected and that too to override the Constitutional frame. It is

(79 Order P.O 13/79) nowhere a protected instrument in absolute sense,

specially its section 3, and cannot be termed to have a sanction of the

Constitution of Pakistan, as restored. Needless to mention that such

findings of the Federal Shariat Court in the reported judgment identified

above were upheld in appeal before the Supreme Court

5

.

26. Thus, it can be safely said that laws which were protected, for a

period, by Article 270A and which cannot withstand the constitutional

mandate and frame, when it was restored, have to fall and sink, and can

be struck down by the Court if found to either overlapping or violating

the fundamental rights protected/ guaranteed by the Constitution or

violative of the Constitutional scheme itself and Article 270A cannot be

read as if it had an effect of saving such laws even after the cut-off date

of 1985 when constitution was restored via Presidential Order-14 of

1985.

4

PLD 1989 FST 50 (Sajjad Hussain v. the State)

5

1993 SCMR 1523 (State v. Sajjad Hussain)

22

27. The supremacy of the Constitution has to be safeguarded. The

laws which could not withstand the legislative competence must yield

their way to parliamentary and constitutional supremacy, and laws after

such scrutiny, if found transgressing such mandate, must be seen to have

been melted down to the frame of the Constitution. Such laws made

during the period mentioned in Article 270A it found violative, must be

eclipsed by the supreme law, i.e. Constitution and it cannot be vice

versa, and laws in derogation of such principle be held ultra vires, such

as in the case of section 3 of P.O 13/79.

28. The 18

th

Amendment played a pivotal role in further

understanding the legislative competence of federation and the

provinces. The first impact created by the 18th Amendment was that

Article 270A, which carved a new dimension along with the 7th Schedule

and the special status as assigned to the laws of the 7th Schedule, was

removed to save the protection. Consequently, for the purposes of

present proceedings, the effect is such that the said entry 50 of FLL (the

only list now available) of the 4th Schedule of the Constitution of the

Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 was amended. Entry 50, as seen

before and after the 18

th

Amendment, is thus essential to be read for

the purposes of their real application. A comparative statement is as

follows:-

Before 18

th

Amendment

After 18

th

Amendment

Taxes on the capital value of the

assets, not including taxes on

capital gains on immovable

property.

Taxes on the capital value of the

assets, not including taxes on

immovable property. (Emphasis

applied).

29. Thus, as could be seen for the purposes of this subject i.e. taxes

on immovable properties, that it has been excluded from the domain of

the federation, the Federal Legislature, and consequently, the

Cantonments cannot levy, impose, charge and/or recover such taxes as

23

levied by it, on immovable property, from the date of restoration of

Constitution and more particularly after 18

th

Amendment, either under

Cantonment Act, 1924 or under Cantonments Urban Immovable Property

Tax and Entertainment Duty Order, 1979. Such levy (levies) by the

Cantonment Board(s) seem to have been initiated in terms of the

Cantonment Act, 1924.

30. The argument of Mr. Munshi insofar as the continuity of the

Cantonment Act and the Presidential Order 13 of 1979 (to the extent of

relevant sections), is concerned, is thus misconceived and devoid of any

power/force within the frame of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of

Pakistan, 1973 to impose a tax on immovable property located in

cantonment areas which itself is part of a provincial territory.

31. The interpretation of Entry 50 recently came up for consideration

before the learned Division Bench of this Court in CP No.D-4942 of 2022

and others which were disposed of vide judgment dated 30.12.2022,

(which is not a reported judgment till date), and another judgment of

Islamabad High Court in the case of Zaka Ud Din Malik

6

. The issue

though, was not directly related to the issue in hand, it is in relation to

capital value tax on foreign movable and immovable assets on residents/

individuals through Section 8(2)(b) of the Finance Act, 2022. The vires of

the said law were impugned before the respective Courts on the ground

that the federation did not have the power to impose a tax on foreign

immovable properties located beyond the territory of the province. With

slightly different reasoning, the two Benches disposed of the matter in

above referred petitions. The Bench in CP No.4942/2022 observed that

the word “not including” used in Entry 50 and the word “except”

appearing in Entry 49 are different and do not give a complete exclusion

and while discussing the impact of Article 142 of the Constitution of

6

Zaka Ud Din Malik v. Federation of Pakistan (2023 PTD 268)

24

Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 and Entry 50, decided that the tax on

immovable property (including tax on capital value on immovable

property) is a provincial subject to the extent of territory of province

and since the properties, which were subject matter of the said

petitions were foreign immovable properties, i.e., beyond the territory

of any particular province, the federal government was empowered to

impose capital value tax on such properties/assets.

32. A similar view, with some altered reasoning, was taken by the

Islamabad High Court, which observed that the tax in question is not a

tax on immovable property but a tax on total assets of resident

individuals. The Islamabad High Court further held that no reference was

made to a particular immovable property while imposing the tax, but

reference was made to the total value of assets of an individual.

Therefore, tax could be levied by the federation under the first limb of

Entry 50.

33. Per judgment, the total value of assets of an individual

immovable property is a tax on the individual’s property. The two limbs

of Entry 50 of the 4

th

Schedule of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of

Pakistan, 1973 was thus read disjunctively while dealing with immovable

properties located and available in a province. The gist however of the

two judgments could be narrowed down that under Entry 50 an

immovable property located within the territory of a province can only

be subjected to a tax under a provincial law and that already exists as

Sindh Urban Immovable Property Tax Act, 1958 and the federation has

no power to levy and consequently authorize Cantonment Boards to levy,

charge and recover such tax under a federal statute. The present frame

of the Constitution thus erodes the effect of Presidential Order 13 of

1979 to the extent of relevant provisions and is eclipsed by 18

th

Amendment carried out/introduced by the parliament and consequently

25

erodes the power of Federation to impose tax on immovable property

under any federal law including but not limited to Act of 1924 and/or

Cantonments (Urban Immovable Property Tax and Entertainment Duty)

Order, 1979.

34. The Presidential Order 13 of 1979 (hereinafter means relevant

section 3) thus cannot be visualized and conceived under the 18th

Amendment, which has altered not only Entry 50 of the 4th Schedule but

has also carried out certain other amendments, such as Article 142 of

the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973. The

Presidential Order 13 of 1979 thus sinks in the frame of restored

Constitution followed by 18

th

Amendment as it cannot withstand the

legislative competence as recognized. In fact amended Article 142(a)

provides that Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) shall have exclusive power to

make laws with respect to any matter in the Federal Legislative List,

whereas 142(c) excludes Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) from legislating on

the subjects not enumerated in the Federal Legislative List whereas

provincial assembly shall have powers to make laws with respect to such

matters not enumerated in the Federal Legislative List. The subject tax

was being dealt with under the 1958 statute when in the Martial Law

regime, the process intervened via the 1979 Order during abeyance of

the Constitution and legislative competence rerouted, which routs of

legislative competence stands restored on the revival of the Constitution

and introduction of 18

th

Amendment to Constitution.

35. The subject in hand also came up for consideration before the

Peshawar High Court in the case of the State Bank of Pakistan

7

, which

read down the Presidential Order 13 of 1979. The principle laid down by

the Peshawar High Court was that subject law, which was relied upon for

the purpose of levying subject tax was promulgated when the

7

State Bank of Pakistan v. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 2022 Peshawar 46)

26

Constitution was in abeyance, whereas on the restoration the

parliament, in particular after the 18

th

Amendment, the relied law

ceased to enjoy its effect to impose any tax on immovable property.

36. On the touchstone of the Constitutional frame, the law on the

basis of which the Cantonment Boards were recovering subject taxes is

thus seen to have opposed the constitutional/legislative competence and

beyond their legal powers and capacity, which could only be termed

ultra vires under the present frame of the Constitution and we hold it

accordingly, on legislative competence alone. There was neither any

question of fresh legislation or validation since there were no such

volume in presence of Act of 1958 which stood revived. Mr. Munshi’s

reliance on Ghulam Musfafa Khan’s case

8

is also not helpful as the said

Bench also interpreted sub-clause 2 and 5 of Article 270A having main

object of conferring validity upon acts, actions and proceedings, done or

taken when Martial Law was in force (para-21).

37. On the count of discrimination, it is claimed that similar and

identical properties are being taxed differently in other similar areas as

well as within the respective cantonments itself. It is claimed that there

is no clear distinction between different municipalities and cantonments

within the city of Karachi as the areas are often territorially mixed up

(overlapping) and well connected. Thus, the imposition of completely

different rates of taxes is not only discriminatory but also violative of

the rights of citizens to conduct trade and business.

38. Although this argument provides a very thin line of distinction as

attempted to be drawn by Mr. Ayan Memon, as different properties

within an area may have different values depending on their age,

condition, suitability etc. but are to be taxed accordingly by the

province specifying the categories/ zones and the rates which are

8

PLD 1989 SC 26

27

supposed to be common in terms of categorization and that could only

be regulated by a province through a yardstick as a regulator. Different

municipalities cannot carve out this distinction independently and

differently for their benefit to impose taxes as individual municipalities

as they required and desired. At times, only a street of 20 feet separates

the municipalities, yet the applicable rates differ only on the count of a

situation of the property in a known municipality/local body area

although facilities may not be upto the mark. This test alone, at times,

was not found to be good classification. If a classification is dependent

upon improved facilities, it counts good, but the purpose could be

achieved by one master/ regulator, i.e. province. If classification does

not rest on good tests, then it is bound to collapse, which, of course,

will create discrimination and there should be one parameter/yardstick

to evaluate. However, one should understand that different properties in

an area/common area may have different values notwithstanding the

area itself is classified as a category but within that category the value

of the property/building may vary, depending upon its characteristics to

evaluate and measure and rental value it may fetch, hence the fact that

property situated in a particular local body/municipality, itself, should

not form the basis of classification. Hence it is all the more necessary

that there should be one regulator to deal with their evaluation with

common tools of evaluations.

39. “Notwithstanding above”, historically tax on annual rental value

of an immovable property was being levied under Chapter 5 of the

Cantonment Act 1924 in line with Section 60 onwards. This provision was

varied and altered in August 2023. Before such amendment Section 60

read as under:-

60. General power of Taxation.-(1) The Board may, with

the previous sanction of the Federal Government, impose

in any cantonment any tax which, under any enactment for

the time being in force, may be imposed in any

28

municipality in the Province wherein such cantonment is

situated

(2) Any tax imposed under this section shall take effect

from the date of its notification in the official Gazette.”

40. It had three prerequisites i.e. (a) there must exist a valid tax i.e.

being imposed in and by any municipality of a province (b) before

levying such tax Cantonment Board must obtain previous sanction of

federal government i.e. federal cabinet as per case of Mustafa Impex

9

and (c) tax must be published in official gazette.

41. As regards the first hurdle that tax can only be imposed under

section 60 by reference to any other valid subsisting law that imposes

such tax in a municipality, it seems that this issue has already been set

at rest by virtue of various pronouncements which ruled that in the

absence of a pre-existing tax, cantonment boards have no power to

impose a tax under section 60. The relied judgments in the case of (i)

Mst. Nargis Moeen

10

– upheld by Supreme Court as Civil Appeal No.2300-

L/2023, (ii) Sultan Jahan

11

– upheld by Supreme Court as 2007 YLR 1547

and (iii) Lahore Station Commander

12

, are in relation to imposition of

“transfer tax” on immovable property and not the subject tax as under

discussion.

42. As far as second prerequisite is concerned, the principle of

Mustafa Impex (Supra) is fully attracted as previous sanction of federal

cabinet had to be obtained prior to imposing tax. It not only stretches

upon a tax being introduced by the Cantonment Board for the first time

in line with other municipalities but also at the time of enhancement of

rates

13

.

9

Mustafa Impex v. Government of Pakistan (2016 PTD 2269)

10

Mst. Nargis Moeen Vs. Government of Pakistan (PLD 2003 Lahore 730)

11

Mst. Sultan Jahan v. Cantonment Board Lahore Cantt. (2007 YLR 1681)

12

Lahore Station Commander v. Col. (R) Muhammad Abbas Malik (2006 CLC 1674)

13

Continental Biscuits Ltd. v. Federation of Pakistan (2011 MLD 1006) (relevant page

1011 paragraph 10)

29

43. Similarly, as far as the third prerequisite is concerned, it must be

published in the official gazette.

44. The Act of 1958 can be taken up as a complete code and cap for

its application for levying, charging and recovering such taxes. It covers

the taxes, rates and the collection method depending upon a common

umbrella for classification, and this classification must not be altered on

the count that an area is being controlled or maintained by another

municipality within the common area with the same facilities around and

within.

45. Act of 1958 describes the rating area where the tax is being levied

and the urban areas include areas within the boundaries of a

cantonment board. Section 3 of Act 1958 is a charging section which

allowed the provincial government to levy tax at the prescribed annual

value of the building and lands which itself is defined in section 5. It

provides a mechanism/procedure as to how such value is to be

ascertained by estimating the gross annual rent at which such land or

building, together with its appurtenances and furniture, could be rented

out for its use or enjoyment. It also eliminates the exercise of different

discriminatory methods (by different municipalities) and assess the same

on the basis of a valuation table officially notified by the provincial

government. It also empowers the local councils, including the

Cantonment Board, to claim a share out of such taxes being levied by

provincial legislation and recover.

46. Since the 18th Amendment has wiped out the requirement for an

amendment under Article 270A(6) as the law already existed hence no

vacuum, and the laws announced during the special regime (7

th

Schedule) were available for a specified period subject to their validity

30

in case of various other laws. Any requirement for an amendment under

Act 270A(6) would only be meaningful if there was no pre-existing law on

the subject by the competent legislation as now and was recognized by

the Constitution of the relevant time. Presidential Order 13 of 1979

would yield its way to the effect of Presidential Order No.14 when the

Constitution was restored to its frame, which has essentially restored

the laws which were in existence prior to the Constitution being kept in

abeyance i.e. from 1979 to 1985 and more importantly when 18

th

Amendment sets the fields of Federal and Provincial competance.

47. Further, in terms of the judgment of Benazir Bhutto

3

(Supra), the

Courts were competent to strike down laws whose competence is beyond

the legislative frame and also any levy flowing through Presidential

Order 13 of 1979 in disregards to the frame of the restored Constitution

and as amended from time to time which we do and maintain

accordingly.

48. We were privileged to hear three independent counsels appearing

for different Cantonment Boards for their diversified views, and

surprisingly, their arguments were found overlapping and opposing each

other. Mr. Munshi insisted that subject levy is nothing but a tax and has

relied upon Section 60 of the Cantonment Act 1924 read with Entry 2 of

the Federal Legislative List, whereas Dr. Farogh Naseem, learned

counsel appearing for some other Cantonment Boards, insisted that it

may be anything but tax and hence cannot come in the clutches of Entry

50. Mr. Munshi relied upon Presidential Order 13 of 1979 and submitted

that it is valid and continue to exist to protect the levy and imposition of

tax on the annual rental value of immovable property. He added that

Presidential Order 13 of 1979 does not violate any fundamental right and

cannot be struck down or read down as the laws were protected under

Article 270A whereas Dr. Farogh Naseem gave different dynamics as far

31

as levy and accumulation of funds are concerned. Mr. Munshi’s above

contention has been responded in the above part of the judgment. In

adjudging such law (1979 Order) our observation would have an effect of

exercise of such powers in rem.

49. Mr. Munshi claimed that since the taxes have been claimed and

recovered for years, therefore, they cannot be challenged as of now,

and the silence to such a challenge amounts to the acquiescence of such

rights. Having examined this contention we find no force in it. These

arguments are not confidence inspiring as it is a settled law that the

constitutionality of any law on the touchstone of any provision of the

Constitution being opposed, could always be challenged and only

because such challenge had not been thrown earlier does not amount to

a acquiescence and would not be immune from a challenge in future. In

enforcing the constitutional frame, the concept of acquiescence is an

alien object.

50. Entry 2 of IVth Schedule of the Constitution of the Islamic

Republic of Pakistan, 1973, which was commonly relied upon by Mr.

Naek, Dr. Farogh Naseem and Mr. Munshi, is in fact a general legislative

entry for internal objects and does not include power to tax. This is also

a settled law that exhaustive taxing entries are between Entry 43 to

53

14

. Reliance can also be made on the recent pronouncement of the

Supreme Court dated 13.10.2023 in the Cantonment Board’s Civil Appeal

No.1363 of 2018 wherein such arguments raised by the Cantonment

Boards in paragraphs 2 and 3 were rejected in paragraph 12.

51. Mr. Munshi also argued that it is a dispute between the federation

and the provinces and hence exclusive jurisdiction to adjudicate the

14

. Pakistan International Freight of Forwarders Association v. Province of Sindh (2017

PTD 1) and Pakistan Mobile Communications Ltd. v. Federation of Pakistan (2022 PTD

266)

32

same lies with the Supreme Court in its original jurisdiction under Article

184 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973. The

argument again is not confidence inspiring as the dispute was raised by

private individuals against such levy and its recovery and was not raised

by any province or federation before us. In an issue of sale tax on

services (supra), the individual consumer/ customer and aggrieved

parties questioned the competence of the federation and the two

governments, i.e. the federation and the provincial governments, strived

for their competence, which was adjudicated upon by this Court

competently.

52. Mr. Naek while treating the subject levy as tax submitted that on

the basis of Article 7 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan,

1973 there was/is no need to rely on any Entry in Federal Legislative

List. He asserted that the Cantonment Boards are local government and

the tax is imposed by the Cantonment under Article 7 of the Constitution

of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 being recognized a state.

53. Our response to it is that Article 7 is only a definition clause and

provides the definition of State. It is neither an enabling nor self-

executing provision of the Constitution. This article does not take us to a

legislative competence. In giving a harmonious application, this Article is

to be read with Article 142 of the Constitution which provides contours

of law making pillars to split organs of state such as federation, senate

and provinces etc. Article 7 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of

Pakistan, 1973 itself ends up by saying that the Federal Government,

(Majlis-e-Shoora/ Parliament), a Provincial Government (Provincial

Assembly), and such local or other authorities in Pakistan as are by law

empowered to impose any tax or cess (emphasis applied). Such powers

could only be drawn not through Article 7 but through Article 142, read

with the 4th Schedule of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of

33

Pakistan, 1973. No purpose could be achieved simply by relying on

Article 7.

54. The argument of Mr. Naek that this genre of tax is not recognized

in any of the Entries itself is fatal to the case of the Cantonment Board

as in the absence of such identity by any of the entries, it would simply

suggest that it is only available for provincial legislation as per Article

142 of the Constitution.

55. Mr. Naek also emphasized on the application of Article 140A, a

newly inserted article in the Constitution, and submitted that

Cantonment Boards, being local government are solely responsible for

their political, administrative and financial responsibility and have the

power to impose any tax on the basis of Article 140A read with Section

60 of Cantonment Act, 1924. First of all, financial responsibilities here

do not mean that they could be construed as powers to levy tax.

Financial responsibilities mean whatever funds are available at their

disposal, its utility should be more transparent and it does not mean that

they would acquire the competence to levy tax. The Supreme Court

decided these arguments in its recent pronouncement dated 13.10.2023

in Cantonment Board’s Civil Appeal No.1363 of 2018. The judgment

provides that neither has Article 163 been made redundant nor has

Article 140A empowered the Federation, including cantonment boards,

to impose the professional taxes.

56. Reference was also made to the Sindh Local Government Act,

2013, that the annual rental value on immovable property is now

devolved upon local government; hence, Cantonment Boards as well are

empowered for the same being local government. Sindh Local

Government Act 2013 specifically excludes Cantonment Boards under

section 14 thereof, hence no power to levy such tax can be derived by

34

the Cantonment Boards from the said Act. No powers could be drawn

from any federal law as it being a provincial subject. It would be

contrary to the reasoning and conclusion drawn by the Supreme Court in

the above referred judgment in the Civil Appeal. Furthermore, section

96 of the Act 2013 states that respective local councils may levy all such

taxes mentioned in the 5

th

Schedule, which include tax on immovable

property, however, in subsection (2) thereof, it is specifically provided

that where such tax is also leviable by the province/provincial

government, the rate of tax imposed by the council shall not be more

than the rate of the government. Thus, the rate, as specified under the

Sindh Local Government Act, 2013 could be the maximum cap. The

necessity of giving this overview is only because Mr. Naek argued and

relied upon the provisions of the Sindh Local Government Act, 2013,

whereas the Federal entity has no role in levying, charging and

recovering it.

57. The argument of the learned Counsels that it is not a tax on

property but on annual rental value and therefore be deemed to be a

tax on income from property, appears weak because this would violate

their own submission as Section 80 of the Cantonment Act, 1924 suggests

that non-payment of tax on annual rental value of immovable property is

a charge created on the property itself. It is therefore clear that as per

section 80 tax is imposed on immovable property and it runs on the

property itself and not on the owner or occupier. Thus, it is a tax on the

immovable property and not a tax on a person's income. Reliance is

placed on the case of Nirmaljit Singh Hoon

15

and Jalkal

16

.

58. Dr. Farogh Naseem took a different stance from the rest of the

counsels appearing for other cantonment boards that impugned levy is

15

Nirmaljit Singh Hoon v. The State of West Bengal 95 1 SCC 707

16

Jalkal Vibhag Nagar Nigam v. Pradeshiya Industrial & Investment Corporation (AIR

2021 SC 5316)

35

not a tax. He submitted that it can be anything but tax and hence

beyond the scope of Entry 50, and on this count alone, the petitions

must fail. He further stretched his argument and submitted that it is a

levy and most likely a fee and is imposed under section 60 of the

Cantonment Act, 1924. He relied upon the case of Workers Welfare

Funds

17

and GIDC

18

where a particular levy was adjudicated to be a fee

on account of quid pro quo, and that since the amount so collected in

the relied judgment was not liable to be subjected to federal

consolidated fund, it is regarded as fee notwithstanding that it

accumulated and pooled in the Federal consolidated fund. He submitted

that in the same way, the levy is not meant for consolidated fund but

the funds of Cantonment Boards itself. He further relied upon Entry 2,

read with Entry 54, to submit that the case of annual rental value on

immovable property is a fee in respect of municipal services; hence,

there is constitutional competence to levy it as it is not within the frame

of Entry 50.

59. In order to understand Dr. Naseem’s contention, we first

considered the argument to the extent of subject levy is a fee. Under

the scheme of the Cantonment Act, 1924, levies are envisaged under

two provisions, as stated above, i.e. Section 60 for levy and collection of

tax and Section 200 for levy of fees. Firstly, if it is recognized as a fee

under Section 200, Cantonment Boards cannot levy or collect such fee as

there would be no statutory competence on the “subject” to levy such a

fee. This has now been settled that for the imposition of any fee,

services under the principle of quid pro quo must have been specified in

the exhaustive list provided under section 200 of the Cantonment Act,

1924. It has been declared that if a particular fee being claimed for a

17

Workers’ Welfare Funds, M/o Human Resources Development, Islamabad and others

v. East Pakistan Chrome Tannery (Pvt.) Ltd. and others (PLD 2017 SC 28)

18