THE STATE OF SHORT-TERM RENTAL

REGULATION IN CANADA

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF 25 MUNICIPALITIES

Anna I. Cameron and Dr. Lindsay M. Tedds

Department of Economics, University of Calgary

Prepared for The City of Calgary

Updated October 2023

This research paper was produced as part of the City of Calgary–Urban Alliance Agreement made

effective on 12 January 2023 (Research Services File Number 1060024).The City of Calgary is

collaborating with researchers at the University of Calgary (UCalgary), under the Urban Alliance

partnership, on a multi-year study of Calgary’s short-term rental market. The goals of the study are

to build a comprehensive evidence base on Calgary’s STR market (including impacts, challenges,

and opportunities), and to use this information to recommend a tailor-made STR policy framework

for Calgary that can be adapted as market conditions change. Engagement with Calgarians and

interested parties is an important component of the Short-Term Rental Study. The authors thank

the City of Calgary for funding this work.

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 4

SECTION 1: UNDERSTANDING STR POLICY ........................................................................................................ 6

THE POLICY TOOLBOX .......................................................................................................................................... 6

A FRAMEWORK FOR STR POLICY ........................................................................................................................ 7

SECTION 2: A BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF STR POLICY IN CANADA .............................................................................. 9

MUNICIPAL POWERS AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT ............................................................................. 9

STR POLICY IN 25 CANADIAN MUNICIPALITIES .................................................................................................. 9

SECTION 3: POLICY GOALS, DEFINITIONS, AND PROHIBITIONS ....................................................................... 13

POLICY GOALS .................................................................................................................................................... 13

DEFINITIONS AND PROHIBITIONS ..................................................................................................................... 18

SPATIAL RULES, QUOTAS, AND MORATORIUMS ............................................................................................... 19

SECTION 4: LICENSING SYSTEMS AND OPERATIONAL AND SAFETY STANDARDS .......................................... 24

LICENCE TYPES ................................................................................................................................................... 24

APPLICATIONS, OPERATIONAL RULES, AND GUEST SAFETY STANDARDS ..................................................... 27

EXTENDING REGISTRATION FRAMEWORKS ..................................................................................................... 28

SECTION 5: TAXATION ....................................................................................................................................... 32

SALES TAXES ....................................................................................................................................................... 32

PROVINCIAL TAXES ON TOURIST ACCOMMODATION ....................................................................................... 33

MUNICIPAL TAXES .............................................................................................................................................. 35

SECTION 6: COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT ............................................................................................... 38

SOFT STRATEGIES .............................................................................................................................................. 38

LICENCE-ORIENTED MEASURES ........................................................................................................................ 38

TRADITIONAL ENFORCEMENT: COMPLAINTS, AUDITS, AND INSPECTIONS .................................................... 39

PLATFORM ENGAGEMENT ................................................................................................................................. 39

SECTION 7: BRINGING IT TOGETHER ................................................................................................................ 43

A TYPOLOGY OF CANADIAN RESPONSES .......................................................................................................... 43

PROMISING PRACTICES ..................................................................................................................................... 45

GAPS AND OPPORTUNTIES ................................................................................................................................ 46

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS ................................................................................................................................. 48

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................................... 50

REFERENCED LEGISLATION AND BYLAWS ....................................................................................................... 55

4

INTRODUCTION

The emergence and continued growth of the short-term rental market has produced many

tensions in communities around the world.

Over the past decade, digital peer-to-peer accommodation platforms have expanded and

transformed the practice of home sharing internationally, producing not only a distinct STR market,

but also a marked change in how we travel and share space. However, the rise of platform-driven

home sharing has been contentious, with the growing STR market garnering dichotomous

characterizations (Dolnicar 2017; Guttentag 2015; Tedds et al. 2021). That is, while it is lauded as

a source of economic benefit and social innovation (Finck and Ranchordàs 2016; Sigala and

Dolnicar 2017), and is celebrated for its responsiveness to consumer preferences and needs

(Guttentag et al. 2018), the market is also viewed as an unwelcome agitator by the hospitality

industry (Benner 2017; Zervas, Proserpio, and Byers 2017), a driver of increased noise and

nuisance in neighbourhoods (Gurran and Phibbs 2017), and a contributor to rising gentrification

(Wachsmuth and Weisler 2018), housing unaffordability (Barron, Kung, and Proserpio 2021; Li,

Kim, and Srinivasan 2022), and over-tourism (Cocola-Gant and Gago 2019).

These tensions are both a consequence of and exacerbated by the fact that much of the STR

activity unfolding in urban areas today challenges notions of home, community, and economy. In

doing so, the STR market encourages new configurations of use and ownership, and actively

contributes to the rearticulation of patterns of urban interaction and development (Davidson and

Infranca 2015). The implications for urban policy, planning, and governance are wide-reaching. For

example, some scholars describe the present iteration of the STR phenomenon as a form of

disruptive innovation, as it alters existing regulatory and planning practices, complicates liability,

and outpaces legislation (Guttentag 2015; Interian 2016). It is therefore unsurprising that the STR

market and its attendant tensions, pressures, and challenges have sparked a proliferation of policy

responses in recent years – most often at the local level – where authorities are seen to be on the

front lines of STR activity and its impacts.

Governments have struggled to regulate short-term rentals effectively.

Effective management of the STR market has been an enduring challenge. Not only has the

platform economy more broadly caught planning scholars and practitioners “on the back foot” (Kim

2019, 261), but its novel structure, activity, and effects also confound standard regulatory

approaches. For one, STR activity does not always map neatly to traditional frameworks and

processes; instead, interactions and effects can occupy grey areas in terms of land use, economic

undertakings, and legality (Johal and Zon 2015; Tedds et al. 2021; Zale 2016), requiring the

delineation of new definitions, categories of activity and use, and most importantly, policy and

regulatory approaches. Authorities also report significant enforcement challenges, since detection

of STR operations can be difficult, local governments may not have sufficient resources and

capacity to address the nature and scale of market activity, and the comprehensive data needed

for effective enforcement are held by platforms (Colomb and Moreira de Souza 2023; Ferreri and

5

Sanyal 2018; Gurran and Phibbs 2017; Leshinsky and Schatz 2018). Finally, the policy and

governance issues raised by the STR market implicate several orders of government and are multi-

faceted, requiring coordination across a range of planning, policy, and legal sub-fields on matters of

property rights, land use, consumer protection, taxation, health and safety, competition, community

planning, and more (Vith et al. 2019).

Most cities in Canada are currently grappling with short-term rental policy, whether by

introducing regulations for the first time or by making changes to existing rules.

These tensions and challenges also apply to Canada’s STR market, which has grown considerably

in recent years. This growth has been met with a significant policy push: as of 2023, major cities in

most Canadian provinces, along with many smaller municipalities and towns, had adopted STR

regulations of some variety. Research on STR policy in the Canadian context is fairly limited,

1

however, with most scholarship maintaining a focus on major urban destinations in Europe and the

United States (Guttentag 2019). As policymakers across Canada continue to grapple with the STR

phenomenon, a strengthened evidence base regarding both the current state and nature of STR

regulation in Canada, as well as gaps, challenges, and promising avenues for reform, will be crucial

to devising effective and equitable policy and governance responses.

This report builds on growing interest in and movement on short-term rental policy in

Canada and is organized around two objectives.

The report is divided into seven sections. Section 1 — Understanding STR Policy — provides a broad

overview of STR policy aims and approaches, and sets out a useful way of thinking about the range

of strategies, policies, laws, and regulations that make up the instrument mix (or policy toolbox)

available to governments for managing the STR market. In Section 2 — A Bird’s-Eye View of STR

Policy in Canada — we introduce the 25 municipalities examined in the report and provide high-

level information about the presence or absence of regulations in these jurisdictions. Sections 3

through 6 compare STR policy in Canadian municipalities across four categories: policy goals,

1

A handful of policy reports (Jamasi 2017; Jamison and Swanson 2021) have examined Canadian regulations, but

there is no peer-reviewed research on the topic. Canadian research is largely focused on pricing (Gibbs et al. 2018);

tourism sector impacts (Guttentag et al. 2018; Sovani and Jayawardena 2017); spatial trends in listings and housing

implications (Combs, Kerrigan, and Wachsmuth 2020); and links to gentrification and financialization (Grisdale 2019).

To assess the first major wave of STR market policy in Canada through a

comparative ‘stock-taking’ of approaches adopted in 25 municipalities.

To draw comparisons and distinctions across responses to inform a discussion

about trends, policy considerations, and wise practices—in Canada and beyond.

6

definitions, and prohibitions; licensing systems and standards; taxation; and compliance and

enforcement strategies. In Section 7 — Bringing It Together — we synthesize the results of our

analysis, discussing promising or wise practices, gaps, and opportunities.

1. UNDERSTANDING STR POLICY

THE POLICY TOOLBOX

Experts have identified a broad array of policy, planning, legal, and regulatory measures and tools –

which we refer to collectively as the STR policy toolbox – from which authorities draw to piece

together management approaches for the STR market.

2

These tools and instruments span a

number of frameworks: zoning and land use planning (e.g., use classifications, spatial restrictions,

parking rules, etc.); tourist accommodation legislation and business licensing (e.g., permits and/or

registration, imposition of operational, safety, and insurance standards); and taxation (e.g.,

accommodation taxes, etc.). Compliance and enforcement measures – from soft mechanisms

involving public awareness campaigns and educational materials, to proactive audits and

inspections – also constitute a key element of STR policy.

Policy tools are used to manage STR activity in five key ways (Colomb and Moreira de Souza

2021)—what we view as policy strategies. These strategies include impacting and controlling the

existence, visibility, and quality of STRs; influencing the overall quantity and geographical

distribution of STRs; managing the distinction and balance between different types of STR

operations; influencing STR platform practices; and taxing STR activity appropriately. These

strategies can be thought of as aligning with or advancing one or more of the following broader

policy goals:

→ managing local impacts (e.g., availability of rental housing ) and preserving neighbourhoods

→ upholding operational and safety standards, while advancing consumer protection

→ recovering community-level costs of STR operations; and

→ fostering high compliance.

Table 1 (p. 7) summarizes the connections among policy goals, strategies, measures and tools, and

the frameworks through which they can be introduced.

2

The scholarship that has shaped our understanding of STR policy and spans case studies (e.g., Ferreri and Sanyal

2018; Grimmer, Vorobjovas-Pinta, and Massey 2019; Lee 2016; Valentin 2020; Verdouw and Eccleston 2023),

comparative papers (e.g., Colomb and Moreira de Souza 2021; Dredge et al. 2016; Furukawa and Onuki 2019;

Hübscher and Kallert 2022; Jamasi 2017; Nieuwland and van Melik 2020; von Briel and Dolnicar 2020), and general

regulatory analyses (e.g., Finck and Ranchordàs 2016; Gurran and Phibbs 2017; Interian 2016; Jefferson-Jones 2015;

Leshinsky and Schatz 2018; Miller 2016).

7

TABLE 1: POLICY MEASURES BY GOAL, STRATEGY, AND RELEVANT FRAMEWORK

Policy Goal

Strategies

Example Measures and Tools

Relevant Frameworks

Manage local impacts

and preserve

neighbourhoods

Influence quantity,

spatial distribution of

STRs

Achieve balance

across STR types

Tiered licensing

Full or targeted prohibitions

Annual night caps

Licence quotas or moratoriums

Parking rules

Zonal/density-based restrictions

Zoning/Land Use Bylaw

Tourist Accommodation

Legislation/Regulations

STR/Business Licence Bylaw

Uphold operational and

safety standards;

advance consumer

protection

Impact/control

existence and quality

of STRs

Permit/registration system for

operators

Pre-licence inspections

Floor and safety plans

Informational requirements

Insurance requirements

STR/Business Licence Bylaw

Tourist Accommodation

Legislation/Regulations

Zoning/Land Use Bylaw

Recover community-level

costs

Tax STR activity

Accommodation tax

Broadening purposes towards

which tax revenues can be applied

(e.g., housing)

Tax Legislation/Regulations

Foster high compliance

Control visibility of

STRs

Encourage platform

practices

Audits

Public education campaigns

Registration databases

Requiring platforms to share data,

support enforcement (listing

removal, grey-outs, licence review)

Data Sharing Agreement or

Memorandum of Understanding

Tourist Accommodation

Legislation/Regulations

STR/Business Licence Bylaw

Note: Frameworks in bold are those over which Canadian municipalities generally have authority.

A FRAMEWORK FOR STR POLICY

A growing body of regulatory scholarship concerned with the STR market also addresses key

principles and priorities for designing policy frameworks – that is, in selecting from the policy

toolbox – with a focus on developing considered approaches attuned to local dynamics and

associated strategies; building a strong foundation through clear definitions and prohibitions;

prioritizing enforcement; and engaging platforms.

On the first point, scholars emphasize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to regulation, and

that processes should differ by jurisdiction, particularly given the distinct consequences

interventions are likely to have (Gurran and Phibbs 2017; Nieuwland and van Melik 2018). To

ensure localized responses, jurisdictions can study community impacts (Major 2016) and

undertake policy mapping exercises (Dredge et al. 2016); these approaches can help authorities to

both understand market effects and complexities, as well as link actions and interventions to

specific impacts (Gottlieb 2013). Such information can also support targeted responses, such as

neighbourhood-level limits on use (Crommelin, Troy, Martin, and Parkinson 2018; Pearce 2016).

Others suggest aligning objectives and management with broader initiatives, such as tourism

8

strategies and destination planning (Gurran 2018), comprehensive community plans and goals

(Gottlieb 2013), and housing strategies (Crommelin et al. 2018).

Second, jurisdictions should, at the outset of strategy development and tool selection, establish

clear definitions and concepts (Dredge et al. 2016), distinguish between or among operator types

(Wegmann and Jiao 2017), and clarify and define use classifications for STR unit types within

planning frameworks (Crommelin et al. 2018; Pearce 2016).

Meaningful enforcement is another priority (Gurran 2018), and can be achieved by introducing

registration requirements that enable authorities to track compliance (Crommelin et al. 2018); by

resourcing dedicated enforcement staff (Leshinsky and Schatz 2018; Wegmann and Jiao 2017) or

forming a STR-specific group within administration (Allen 2017); and by undertaking targeted

enforcement (Major 2016). Some also argue that compliance rates may be improved by avoiding

overly burdensome regulatory schemes (Guttentag 2015; Major 2016), particularly as confusing

requirements spanning multiple frameworks and regulatory bodies can undermine voluntary

compliance on the part of operators (Leshinsky and Schatz 2018).

Finally, frameworks should impose greater obligations on platforms (Colomb and Moreira de Souza

2021; Finck and Ranchordàs 2016; Leshinsky and Schatz 2018; Pearce 2016). This could involve

agreements that require platforms to impose online controls or nudges (Guttentag 2015), including

sharing information about requirements with prospective operators, creating mandatory licence

fields, and deactivating listings after a night cap is met. Platform collaboration can also support

access to data on listing and

operator types, patterns of use,

and the nature of violations,

thereby enabling adjustment

as the market changes.

The adjacent diagram depicts a

multi-dimensional

understanding of STR policy,

which builds on the principles

and priorities discussed above,

and takes into consideration

the range of policy tools

available to authorities for

regulating STR activity. These

dimensions can be imagined as interlocking processes that can, when enacted together, support

comprehensive and strategic management of the STR market. This visual also reflects the

knowledge that, in practice, various components of STR policy are interdependent and mutually-

reinforcing. Later in the report, we’ll use these dimensions to structure our comparative analysis.

9

2. A BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF STR POLICY IN CANADA

MUNICIPAL POWERS AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT

Though policymaking on the topic of the STR market has primarily taken place at the local level in

Canada, these efforts unfold within – and are likewise constrained by – the structures of Canada’s

federal arrangements. This not only means that all orders of government in have some role to play

in STR policy, but also that municipalities, given the constitutional division of powers, are limited in

what form their role can take. We need to be aware of these relationships and constraints when

examining the actions of local governments and thinking about new strategies and approaches.

One reason for examining the federal context is that a range of provincial, territorial, and federal

laws also apply to STRs, and therefore complement municipal rules within what can be viewed as

multi-level governance structures (even if they are not explicitly coordinated as such). These include

provincial legislation and regulations that establish and enforce licensing systems and operating

standards for tourist accommodation (including STRs), and federal and provincial/territorial taxes,

such as income, sales, and accommodation taxes, which apply to STR transactions. An

understanding of these frameworks and their interaction with local policies is necessary to piece

together an accurate picture of how the STR market is managed in Canada.

The federal context also reflects particular constitutional arrangements, which have the effect of

limiting how governments of different orders can contribute to policymaking. Specifically, Canada’s

constitution establishes municipalities as an area of provincial legislative competence, meaning

that local governments have legal authority over such areas as land-use, business licensing, and

taxation only to the extent that these powers have been devolved to them through provincial

statutes. These arrangements between provincial/territorial and municipal governments vary

considerably by province/territory and by municipal government (based on differences in size, role,

and function), and are often reflected in city charters. This feature of Canadian federalism

complicates the comparability of regulatory approaches, both within the Canadian context and

especially when looking at measures adopted internationally.

STR POLICY IN 25 CANADIAN MUNICIPALITIES

In this report, we compare STR management efforts in 25 Canadian municipalities across the four

dimensions of STR policy frameworks outlined in Section 1. We selected jurisdictions on the basis

of geographic and contextual representation, in an aim to represent not only the whole of Canada,

but also a range of urban contexts – from bustling metropolises like Toronto, to growing mid-sized

cities like Halifax, to mountain and resort towns that fuel domestic and international tourism. As a

result, our review includes all thirteen provincial/territorial capitals, plus the Canadian capital of

Ottawa; six municipalities that are not capitals, but which are the largest metropolitan centre in the

province; and five travel destinations of various kinds (e.g., mountain towns, summer vacation

hubs, tourist centres). Table 2 (p. 10) provides an overview of the presence and absence of STR

10

policies, including taxes, in the municipalities examined in the report. We supplement this with a

visual depiction of the evolution of STR policy in Canada over the past decade (Table 3; pp. 11-12).

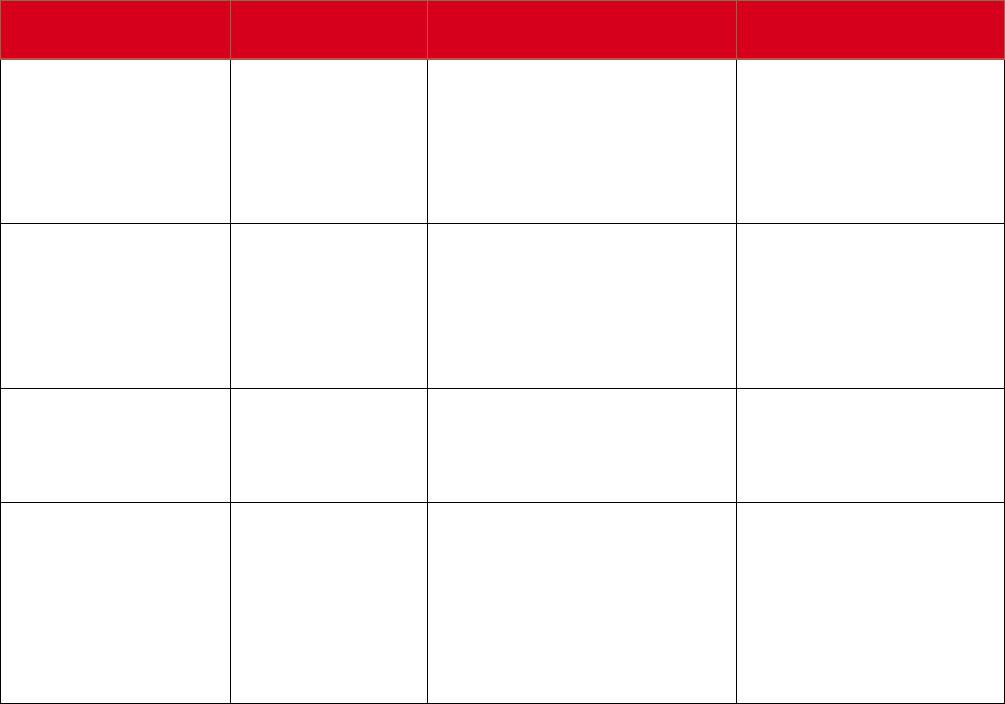

TABLE 2: SNAPSHOT OF STR POLICIES IN CANADIAN JURISDICTIONS

Province/territory

Capital city

Large city

Tourist destination

BRITISH COLUMBIA▲

Victoria

Vancouver

Tofino

Kelowna

Whistler

ALBERTA▲

Edmonton

Calgary

Banff

SASKATCHEWAN

Regina

Saskatoon

MANITOBA

Winnipeg

Churchill ▲

ONTARIO

Ottawa▲

Hamilton▲

Niagara-on-the-Lake▲

Toronto▲

QUÉBEC▲

Québec City

Montréal

NEW BRUNSWICK

Fredericton▲

NOVA SCOTIA

Halifax▲

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

Charlottetown▲

NEWFOUNDLAND & LABRADOR

St. John’s▲

Legend

YUKON

Whitehorse

Accommodation Tax

▲

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

Yellowknife

Measures in Force

NUNAVUT

Iqaluit

Measures Expected

Note: In British Columbia, the province oversees tax legislation; however, revenue is received and allocated locally.

As of September 2023, all municipalities in our review, with the exception of Whitehorse and

Winnipeg, had some form of STR policy in place — whether a tax, land-use rules, or a licensing

scheme — either locally or at the provincial/territorial level. Notably, four provinces — Quebec, Nova,

Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland — have adopted licensing systems for tourist

accommodation, including STRs.

3

Saskatoon and Winnipeg are the only provincial municipalities in

which an accommodation tax is not currently applied to STR bookings. In Winnipeg, Council has

approved a regulatory framework for STRs, which includes a licensing system and the extension of

the existing Accommodation Tax to STR bookings (City of Winnipeg 2023), and bylaw development

is underway (Unger 2023). In Hamilton, a licensing system will be launched in December 2023 and

enforced starting in January 2024 (City of Hamilton 2023).

3

This report does not consider legislation proposed recently in British Columbia through the Short-Term Rentals

Accommodations Act. For information, see https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/housing-tenancy/short-term-rentals.

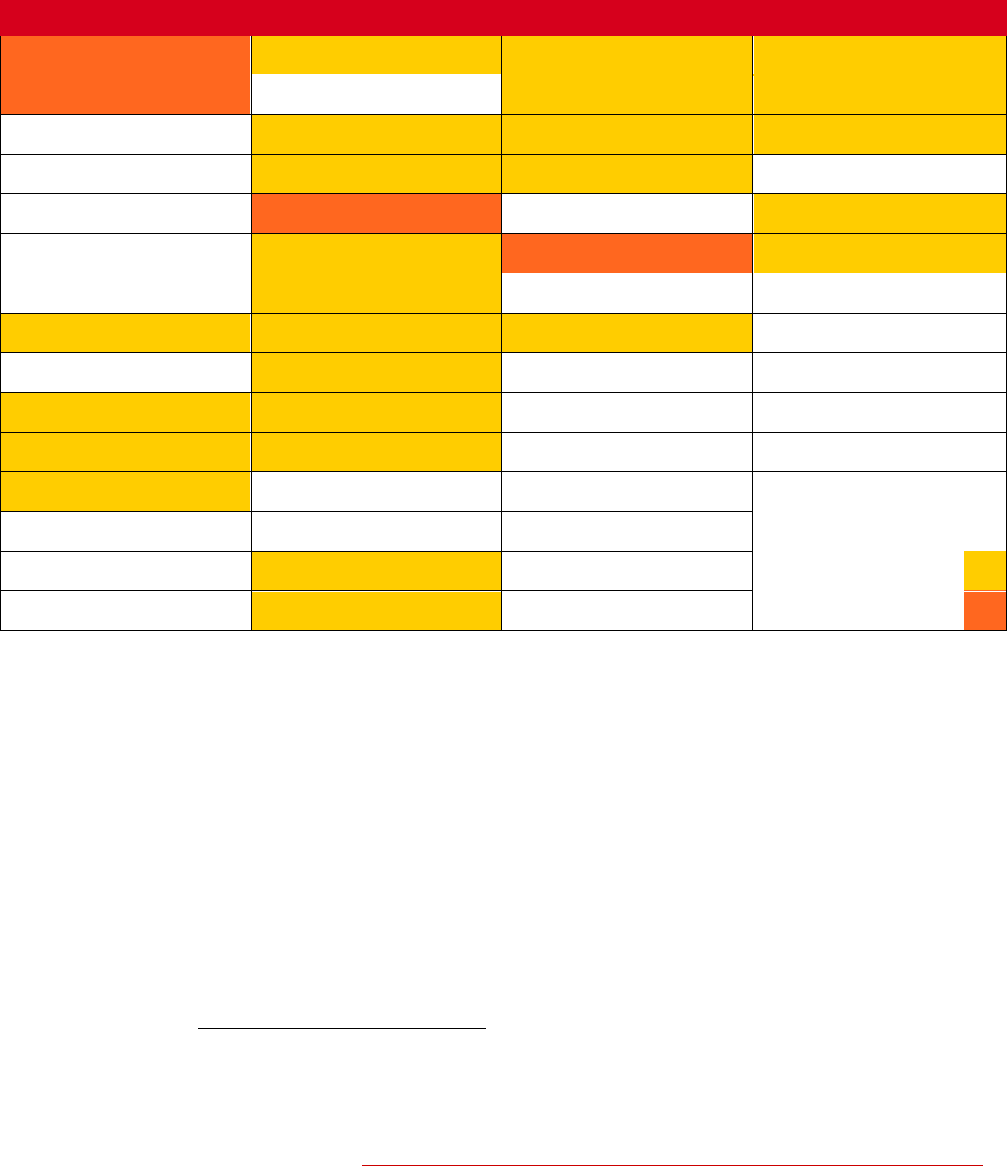

TABLE 3: EVOLUTION OF STR POLICY IN CANADIAN JURISDICTIONS

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

BC

proposed

Kelowna

Tofino

Vancouver

Victoria

Whistler

ALBERTA

Banff

moratorium

Calgary

amendments in force Jan’24

Edmonton

SASK.

Regina

Saskatoon

MANITOBA

Churchill

Winnipeg

Legend

licensing

zoning

ONTARIO

taxation

Hamilton

amendment

forthcoming

12

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

Niagara-on-

the-Lake

Ottawa

Toronto

QUÉBEC

Montréal

Several boroughs, which have authority over zoning, have introduced rules for STRs

Québec City

NB

Fredericton

Only applies to tourist accommodation with 6+ rooms

Nova Scotia

Halifax

rental registry

PEI

Charlottetown

NL

St. John’s

YUKON

Whitehorse

NWT

Yellowknife

NUNAVUT

Iqaluit

13

3. POLICY GOALS, DEFINITIONS, AND PROHIBITIONS

Effective policy frameworks for the STR market rest on the articulation of guiding principles,

objectives, and/or policy intent, as well as the establishment of clear definitions pertaining to the

market. Once these fundamental aspects have been determined, authorities can work to outline

operation types and market actors, as well as set dwelling-specific, use-based, and spatial

restrictions that advance principles and goals. Together, these decisions create a foundation from

which effective licensing, management, and enforcement can be pursued: they establish the

bounds of permissible activity given stated policy objectives and within the context of local

strategies, constituent policies, and the bylaws designed to enact them.

POLICY GOALS

Governments articulate policy goals in a number of ways. At the local level, city councils (or

individual councillors) can raise items for study and reform in response to emerging issues and

municipal goals, and often outline policy objectives at the same time. Policy rationale is often also

articulated through guiding principles or objectives for regulatory development put forward by

Administration in reports to Council. Municipalities also develop community plans, which establish a

vision, set out policies, guide the planning and regulatory strategies pursued within a jurisdiction,

and provide justification for the use of tools, such as zoning and business licensing. Depending on

the jurisdiction, these plans can specify direct policy actions on granular issues including STR

reform. Other strategic documents, such as housing strategies, can communicate clear policy

objectives and actions in a similar way.

Understanding the policy rationale and objectives guiding STR reform is useful when comparing

approaches across jurisdictions, as it can help link regulatory responses to key issues in the

market, as well as broader local dynamics. Such information can support comparisons across

jurisdictions, particularly in terms of establishing wise practices that account for local differences in

capacity, instrument availability, economic context, housing issues, and more. It can also support

assessments of the effectiveness and suitability of existing regulatory approaches: that is,

understanding policy intent is vital when assessing whether regulations are achieving their purpose.

In Table 4 (pp. 14-16), we summarize the core objectives informing STR policy in the 25

jurisdictions in our review. To establish a sense of policy intent and identify guiding objectives for

STR policies adopted in the jurisdictions in this review, we examined Community/Official Plans,

Council policies, staff reports to Council on STR reform, and housing strategies. Overall, this review

indicates that curtailing or preventing housing market impacts – particularly in the long-term rental

market – is a key policy objective for many jurisdictions, with over half of municipalities indicating

this as a policy objective in some way. Other common objectives include limiting impacts on

communities and neighbours (including in terms of noise and nuisance), ensuring ample tourist

accommodation to support local markets, and enabling primary residence STR income as a stream

of income for residents.

14

TABLE 4: OBJECTIVES DRIVING STR POLICY IN CANADA

Policy intent

Kelowna

Guiding Principles - Regulation: Protect LTR housing supply. Prevent negative impacts on neighbours. Ensure equity among STR providers. (City of Kelowna 2018)

Community Plan: Objective 4.14. Protect rental stock in Urban Centres / Policy 4.14.3 STRs: Ensure STR limits impact on LTR supply. Objective 5.13. Protect rental housing stock

(Core Area) / Policy 5.13.3. STRs: Ensure STRs do not negatively impact LTR supply. Objective 6.10. Prioritize construction of purpose-built rental housing (The Gateway) / Policy

6.10.5. STRs: Ensure STR limits impact on the LTR supply.

Housing Strategy: Actions - Update regulations to protect rental stock from impacts of STRs: Develop policy & regulations regarding STRs to address impacts to the rental market.

Tofino

Community Plan: Future Land Use: Restrict development of commercial accommodation, including STRs. Housing Policies: Discourage STRs in residential zones. Monitor vacation

rentals to ensure no negative impact on LTR stock, existing neighbours/neighbourhoods. (Corporation of the District of Tofino 2021)

Vancouver

Regulatory Goals: Bring STR industry into regulatory framework. Ensure PR requirement is met to protect LTR stock. Improve building, fire safety. Encourage neighbourhood fit.

Optimize enforcement & ensure regulatory equity. Increase public understanding of noncompliance repercussions. Harmonize compliance. Recover costs in long-term [Staff Report

to Council (City of Vancouver 2017)]

Housing Strategy: Ensure existing housing is serving people who currently or intend to live and work in Vancouver. Key Actions: Implement Short-Term Rental regulations to protect

long-term renters while also enabling homeowners and renters to make supplemental income from their principal residence.

Victoria

Housing Strategy: Goal One: Focus on Renters – STR Policy Review - Review the STR policy and proactive enforcement efforts and consider opportunities for directing program

revenue to affordable housing.

Whistler

Council Policy: Guiding Principles: Protect VA bed base; maintain warm beds; support visitor experience service quality; provide range of accomm types, arrangements; support

efficient property management, operations, maintenance & reinvestment; provide clarity & certainty regarding use requirements & rental agreements; remove RMOW from property

mgmt; prohibit nightly rentals in res. areas. Res. Accomm.: Maintain & reinforce zoning restrictions, business regs to prohibit TA use; Maximize use of res. properties to support

employee housing; Implement reg. changes that will facilitate active enforcement; Work with property mgmt companies, platforms, service providers to support zoning & business

regs; Enforce against illegal rentals using available tools & leg. powers. Amend business regs to prohibit marketing of illegal rentals, adopt available adjud. processes; Recognize &

maintain B&B, pension zoned properties within res. areas, but do not support new. Amend zoning for B&Bs to have onsite manager. (Resort Municipality of Whistler 2017)

Community Plan: Visitor Accommodation - "VA and tourist capacities have achieved a healthy balance. Nightly and TA have not displaced residential uses and housing in Whistler's

residential neighbourhoods. Goal - 5.5.l Maintain appropriate supply and variety of VA to support Whistler's sustainable year-round tourism economy. 5.5.1.3. Policy - Balance the

VA supply with Whistler's resort community capacity and growth management principles; 5.5.1.8. Policy - Actively enforce against illegal VA use of residential properties.

Banff

Land Use Bylaw purpose: To provide for orderly, economic, beneficial, & environmentally sensitive development of Town given objectives to: Maintain Town as part of World

Heritage Site; serve as a centre for accommodation & other goods & services for Park visitors; serve as centre for widest possible range of interpretive & orientation services to

Park visitors; maintain & enhance community character complementary to surrounding natural environment; provide comfortable living community for persons who need to reside

in the Town.

Calgary

Regulatory Goals: To ensure appropriate level of safety and regulatory oversight – business licence, land use, and safety code (fire and building) requirements, as well as bylaw

education and compliance measures – commensurate with scale and purpose [STR Scoping Report (City of Calgary 2018)].

Edmon

-

ton

Regulatory Goals: Edmonton’s short-term rental regulations aim to enhance livability in the city by streamlining rules for short-term rental operations while balancing the industry’s

interests with those of neighbourhoods and other businesses.

Regina

Regulatory Goals: Allow residents to rent out all/part of home on short-term basis; increase inspections for health & safety imposed by other legislation. Encourage compliance,

reduce enforcement costs by minimizing barrier, focusing enforcement on secondary properties. Address concerns about nuisance in neighbourhoods (City of Regina 2020)

Community Plan: Major Institutional Areas - 7.19 Encourage related housing, services and amenities, including hotels or short-term accommodations, to locate near or adjacent to

major institutional areas.

Saskatoon

Regulatory Goals: To update existing land use & licensing regulations to ensure they remain relevant to changing industry by amending standards in line with the scale of business

operation, while minimizing land use conflict, impact on residential characteristics of neighbourhoods, rental housing availability [Admin Report (City of Saskatoon 2022b)]

15

Niagara

-on-the-Lake

Regulatory Goals: To deliver on strategy to deliver Smart and Balanced Growth with emphasis on the accommodation industry. To ensure that the growth of STAs is well managed;

that licensing application process is clear, easy to understand, simple to process; that STAs contribute to a prosperous and diversified sector; that STAs contribute to town

infrastructure, add value to the industry and that the sector benefits not only the rental owners but residents as a whole:

• Ensure that traditional residential neighbourhoods are not turned into tourist areas to the detriment of long-time residents • Ensure any regulation of STRs does not negatively

affect property values (and property tax revenue)• Ensure homes are not turned into pseudo hotels or “party houses”• Minimize public safety risks and noise, trash and parking

problems often associated with STRs without creating additional work for Enforcement Officers or Niagara Regional Police department • Give permanent residents option to

occasionally utilize their properties to generate extra income from STRs as long as all of the above mentioned policy objectives are met and subject to all local by-laws• Any by-law

must be clear, precise, simple to understand and address these goals and objectives

Official Plan: STAs important part of cultural landscape, tourism infrastructure, economy of Town; will be regulated through zoning bylaw, site plan approval, licensing bylaw; must

not negatively impact agricultural production, remove land from production; STA in/near cultural heritage resources could contribute to conservation of character & provide

financial support for ongoing maintenance of heritage attributes. (Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake 2019)

Ottawa

Regulatory Goals: Maintain quality and character of neighbourhoods by mitigating nuisance, other negative effects; protect long-term housing availability and affordability for

residents [Staff Report – Short-Term Rental By-Law (City of Ottawa 2021)]

Official Plan: 4.2 Housing - 4.2.2 Maximize the ability to provide affordable housing throughout the city: In approving development, the City will […] strictly control the diversion of

LTR units and residential land to dedicated STR use, including through online sharing economy platforms that enable dwelling units to be rented to the travelling public.

Toronto

Regulatory Goals: Ensure safety for consumers and neighbours and promote quality of life in neighbourhoods; prevent decrease of availability and affordability of rental housing;

promote tourism by supporting innovation in the accommodations sector; ensure tourist accommodation providers have equitable regulations and tax requirements; allow

residents to occasionally rent their own homes for short periods; ensure rules and regulations are clear for residents, property owners and platforms [Staff Report (City of Toronto

2016)]

Montréal

Regulatory Goals (Province): 2021 Modernization: Reduce red tape, costs for operators. Simplify rules for better understanding and compliance. Support and equip municipalities

and Revenu Québec with the supervision of tourist accommodation. 2023 Amendments: Prohibit digital platforms from listing STRs without registration numbers or the expiry date

of the registration certificate, strengthen compliance with Act and Regulations; support Revenu Québec in the fight against illegal accommodation and municipalities in the

application of their regulations. Objectives: Remove from digital platforms listings with no registration number or number that is false, inaccurate, suspended or cancelled; Ensure

the validity of registration numbers displayed on listings on digital platforms; Enable customers to know whether the rented STR is registered and in accordance with municipal

regulations.

QC City

Regulatory Goals (City): Preserve historic & tourist districts, preserve quality of life for residents; remain attractive destination for visitors; provide diverse accommodation that

meets visitor expectations (STRs can be part of solution); consider perspectives of all stakeholders; provide feasible regulations that can be monitored, to facilitate compliance

[Guidelines - Tourist Accommodation Working Group]

Regulatory Goals (Province): Same as above (Montréal)

Halifax

Regulatory Goals (Province): Extend registration requirements to all operations (including those in a primary residence). The intent is to “help create a level playing field for

operators,” and to “provide clearer data about STRS, help municipalities identify short-term rentals in their communities to improve enforcement of bylaws.” [Rationale for recent

amendments (Tourism Nova Scotia 2022)]

Regional Plan: While STRs can provide unique opportunities for tourism, they can also have impact on LTR market if unregulated. HRM intends to provide consistent approach to

regulation of STRs throughout municipality to protect housing supply while still providing opportunities for tourist accommodations. HRM shall, through applicable land use by-laws,

establish special provisions to permit STRs in residential zones, where the STRs are located within the operator’s primary residence; and in zones where commercial tourist

accommodation uses are permitted (Halifax Regional Municipality 2022)

Charlottetown

Regulatory Goals (Province): Safety, cleanliness, education & prevention measures. Program protects consumers & PEI’s reputation as quality destination (Tourism PEI 2023)

Regulatory Goals (City): The proposed regulatory framework has been designed to provide opportunities for residents to benefit from the STR economy while establishing

appropriate measures that minimize the negative consequences of STR activities that impact housing, generate nuisances, and disrupt community harmony. The concerns of

ensuring the health and safety, consumer protection and the economic and social well-being of the municipality have been the focus of these proposed regulations.

Official Plan: Sustaining Neighbourhoods: Objective: support provision of suitable commercial & institutional needs, employment opps., community-based services, public

amenities. Policy: ensure STR in res. area restricted to operator’s PR, be of scale compatible with character of the surrounding neighbourhood. Supporting Home Occupations:

Objective: support creation, operation of B&B & tourist homes in all residential zones. Policy: require all operators of B&B & tourist homes be registered & licensed by Province &

City. [(Department of Planning & Heritage 2022)].

16

St. Johns

Regulatory Goals (Province): “For quite some time now, our tourism and hospitality stakeholders have been calling for a more level playing field between licensed and unlicensed

accommodations. While the new Act and regulations alone will not address all issues, it is an important step forward. The Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts and Recreation will

now be aware of all operators offering overnight accommodations, and will have the ability to provide regulation, improving our visitor experience.” (Government of Newfoundland

and Labrador 2023)

Yellow

-

knife

Regulatory Goals: The City needs an approach that maximizes the benefits of STR while managing impacts on neighbourhoods and providers of licensed accommodations.

Iqaluit

General Plan: While STRs can provide economic and tourism opportunities for the City and income for residents, they can also remove housing stock from the market, and impact

full-time residents. Policies: STRs shall be permitted in all residential zones and commercial zones where a dwelling unit is permitted; the use of any dwelling unit as a full-time STR

shall not be permitted, except for a STR contained in a secondary suite; the Zoning Bylaw will define STRs and contain provisions to ensure they do not create a nuisance [General

Plan (The Corporation of the City of Iqaluit 2020)]

TABLE 5: STR DEFINTIONS IN CANADIAN POLICY FRAMEWORKS

Definitions

Kelowna

STR Accommodation: The use of a dwelling unit or one or more sleeping units within a dwelling unit for temporary overnight accommodation for a period of 29 days or

less [Zoning Bylaw]

Tofino

STR: Use of a dwelling to provide tourist accommodation: that is, the commercial provision of temporary overnight accommodation to the traveling public for a period of

less than 1 month [Zoning Bylaw]

Vancouver

STR Accommodation: Temporary accommodation in a dwelling unit, or in a bedroom or bedrooms in a dwelling unit, but does not include temporary accommodation in

any Bed and Breakfast Accommodation or any Hotel [Zoning Bylaw]

Victoria

STR: Renting of a dwelling, or any part, for a period of less than 30 days - includes vacation rentals [Short-Term Rental Regulation Bylaw]

Whistler

Vacation rental business: Providing accommodation to paying guests in a dwelling unit, but does not include the rental of dwelling units for residential purposes for a

month or more under a residential tenancy agreement pursuant to the Residential Tenancy Act [Tourist Accommodation Rental Bylaw]

Banff

B&B Home: the single detached dwelling of an owner […], who is an eligible resident of Banff National Park, resides therein as principal residence, containing at least 1

bedroom for exclusive use and containing accessory guest accommodation in rooms for the purposes of supplying temporary living accommodation to the public, for a

fee. [Land Use Bylaw]

Calgary

STR: business of providing temporary accommodation for compensation, in a dwelling unit / portion of a dwelling unit for periods of up to 30 consecutive days [Business

Licence Bylaw]

Edmonton

Residential Rental Accommodation (Short-Term): Business that provides temporary lodging on premises where persons may rent all/part of a residential property for 30

consecutive days or less, including B&Bs, lodging arranged through home-sharing services [Business Licence Bylaw]

Regina

Short Term Accommodation: temporary accommodation in a unit/room/rooms in a unit, for a fee for a period of less than 30 days but does not include emergency

shelters operated by non-profits/ government institutions. [Short Term Accommodation Licensing Bylaw]

Saskatoon

Homestay: dwelling within principal residence of the host, in which rental accommodations are provided to guests for tenancies of less than 30 days.

STR property: dwelling that is not primary residence of host [Business Licence Bylaw]

Churchill

STR: renting out of a principal residence for a period to which the Residential Tenancies Act does not apply [Accommodation Provider Licensing Bylaw]

17

Niagara-on-the-

Lake

STR: use of a building for overnight guest lodging for a period of not more than 28 days and includes Bed and Breakfast Establishment, Cottage Rentals, Villas, Country

Inns, and Vacation Apartments [Bylaw for the Licencing, Regulating and Governing of Short-Term Rentals]

Ottawa

STR: transient accommodation in whole/part of residential unit for a period of less than 30 consecutive nights, and: marketed or brokered by a STR platform; not a

rooming house or hotel; includes B&B, cottage rental, Dedicated STR [Short-Term Rental Bylaw]

Toronto

STR: All/part of a dwelling unit used to provide sleeping accommodation for any rental period less than 28 consecutive days in exchange for payment; includes bed and

breakfasts, but not hotels or motels. [Licensing Bylaw]

Quebec

tourist accommodation: establishment in which at least one accommodation unit, such as a bed, room, suite, apartment, house, cottage, ready-to-camp unit or

campsite, is offered for rent to tourists, in return for payment, for a period not exceeding 31 days.

principal residence: establishments that offer, following a single reservation, accommodation in the principal residence of the natural person who operates the

establishment for one person or one group of related persons at a time.

general tourist accommodation: establishments other than principal residence establishments and youth tourist accommodation establishments that offer

accommodation in the form of one or more types of accommodation units, such as hotels, bed and breakfasts, tourist homes, cottages and outfitters [Tourist

Accommodation Act]

Montréal

commercial tourist home: establishment where accommodation is offered to the travelling public in a furnished residence with a kitchen, excluding accommodation

offered by a person in their home.

collaborative tourist home: establishment where accommodation is offered to the travelling public by a person in their home. [these definitions are established by

boroughs, and thus vary (the above is set out in the Urban Planning Bylaw for Le Plateau-Mont-Royal)]

Québec City

commercial tourist accommodation: rental of tourist accommodation to the public for payment for a duration of 31 consecutive days or less (not in a principal residence

– same class as hotels)

collaborative tourist accommodation: rental by an occupant of an entire residence, main room, or bedroom therein to tourists for a period of 31 consecutive days or

less.

Fredericton

STR Accommodation: A dwelling unit use in whole or in part to provide sleeping accommodation for a period of less than 28 days [Zoning Bylaw]

Nova Scotia

STR: Provision of roofed accommodation to single party or group, for payment or compensation, for a period of 28 days or less [Tourist Accommodations Registration

Act]

Halifax

Short-term rentals are dwelling units rented out by property owners or tenants that provide temporary overnight accommodation. Short-term rentals may be offered as a

rental of an entire dwelling unit, or in the form of a short-term bedroom rental, where individual bedrooms are rented out separately. This form of short-term rental is

often associated with bed and breakfasts, but can also include less formal types of tourist accommodation such as lodging houses [Regional Plan]

Prince Edward

Island

Tourist establishment: an establishment that provides temporary accommodation for a guest for a continuous period of < 1 month; includes building, structure, place in

which accommodation or lodging, with or without food, is furnished for price to travellers (cabin, cottage, housekeep. unit, hotel, lodge, motel, inn, hostel, B&B, resort,

travel trailer, vehicle park, houseboat, camping cabin, campground [Tourism Industry Act]

Charlottetown

STR: The rental of an entire dwelling unit or a portion of a dwelling unit that serves as the operator/host’s principal residence for a period of less than 28 consecutive

days and defined as a permitted use by way of a Tourist Home.

Tourist Home: Temporary accommodations for travelers or transients within a Principal Residence of the operator/host that is not a company or corporation for the

exclusive use of one (1) guest and their party of guests, such as a Short-term rental lodging but a Bed & Breakfast, Hostel, and Hotel are separate uses and separately

defined [Zoning & Development Bylaw]

Newfoundland

and Labrador

Short term rental: the provision of an accommodation for compensation to an individual or group of individuals for overnight lodging for a period of 30 days or less

[Tourist Accommodations Act]

Yellowknife

STR Accommodation: the business of providing temporary accommodation for compensation in a dwelling unit where persons may rent a portion or all of the premises

for 30 consecutive days or less [Business Licence Bylaw]

Iqaluit

STR: all or part of a dwelling unit used to provide sleeping accommodations for any rental period that is less than 30 consecutive days in exchange for payment and

includes a bed and breakfast but does not include a boarding house, hotel or shelter [Zoning Bylaw]

18

DEFINITIONS AND PROHIBITIONS

Once policy intent has been established, policymakers turn to zoning and licensing bylaws – and in

some cases, a bylaw or legislation specific to tourist accommodation or the STR market – to set

basic definitions (Table 5; pp. 16-17) and place limits on the scope, nature, and operation of STR

activity in line with set objectives (Table 6; pp. 22-23). Land-use designations and zoning, for

example, are tools used by local authorities to draw bounds around and manage the types, extent,

and spatial dimensions of land use in a given community and include stipulations regarding

building types and characteristics (e.g., size, height, external character, etc.), as well as the uses

that can be carried out within them. In the STR context, zoning is often used to preserve community

character, as well as limit the negative local impacts of STR activity, such as reductions in long-term

rental (e.g., by preventing commercialized STR operations in residential areas). Licensing bylaws

can also contain similar provisions, such as those which impose moratoriums on the granting of

new licences if vacancy rates fall below a certain level.

Most jurisdictions we reviewed have established residency-base rules, whereby restrictions are

placed on STR operations based on whether the unit is a principal residence or a secondary or

investment property. The restriction of STR operations to a host’s principal residence is one of the

primary mechanisms used by authorities to address community- and housing-level impacts of the

STR market, based on the rationale that commercialization of the market leads to the depletion of

long-term housing stock. Seven jurisdictions in our review (Vancouver, Victoria, Banff, Ottawa,

Toronto, Charlottetown, and Iqaluit) impose a firm restriction on commercial or secondary property

STRs, requiring that all operations take place in the permanent residence of the host.

4

However, in

all of these jurisdictions, one is permitted to operate an STR in an accessory or secondary dwelling,

provided that either the host occupies and is present in the principal dwelling on the property

(Banff, Charlottetown, and Iqaluit) or the dwelling serves as the host’s principal residence

(Vancouver, Victoria, Ottawa, Toronto). In other jurisdictions, such as Fredericton, principal

residence STRs are the only form of STR use permitted in residential zones.

Some jurisdictions also impose an additional layer of rules pertaining to entire-unit STR operations.

In particular, Banff prohibits entire-unit operations altogether—even if the host is simply out of town

and wishes to rent out their home. In Tofino, an STR can only be operated on a lot with two dwelling

units (i.e., a single detached home, secondary suite thereof, or caretaker’s cottage), and a

permanent resident must be present in the dwelling that is not an STR (though the Zoning Bylaw

contains an exception for townhouses in the CD(EL) zone, which can host up to five guests in the

absence of the resident. In several additional jurisdictions, entire-unit operations are restricted

4

In Victoria and Ottawa, regulations account for non-compliant operations that were previously authorized under former

rules, in some cases allowing such properties to operate STRs under legally non-conforming status. Further, in Ottawa

one is permitted to obtain a second licence for a cottage-based STR.

19

based on use type and zone, and are also subject to an annual night cap. We discuss these

elements below, in relation to spatial rules.

Finally, STR operations are permitted in most legal dwelling types, including single-detached homes,

apartments, duplexes, townhouses, and accessory units (e.g., basement, secondary, garden, and

laneway suites). However, several notable restrictions exist across jurisdictions. These include

explicit prohibitions in community/affordable housing (Vancouver and Ottawa); employee housing

(Whistler and Banff); apartments or multi-family dwellings (Tofino, Banff, and Charlottetown);

duplexes and townhouses (Tofino and Whistler), two-family dwellings (Tofino); secondary suites

(Kelowna); accessory and auxiliary dwellings (Kelowna, Tofino, Whistler, and Ottawa); buildings that

house a group home (Kelowna, Fredericton); and all buildings that are not occupied as a single-

detached dwelling for a minimum of four years (Niagara-on-the-Lake), with an exception for

vacation apartments. Further, regulations in some jurisdictions make specific mention of

prohibitions in a vehicle (Yellowknife, Toronto, Ottawa, Regina, Vancouver, Tofino, and Kelowna),

tent or temporary structure (Regina, Kelowna, and Tofino), and trailer (Regina and Ottawa). Overall,

it is notable that the majority of dwelling-based restrictions exist in those jurisdictions which are

smaller in size, have economies centred around tourism, and thus face particular challenges in

balancing visitor accommodation with resident quality of life and access to housing for the local

workforce.

SPATIAL RULES, QUOTAS, AND MORATORIUMS

In addition to the above restrictions, authorities impose zone- and site-based rules, licence-based

limits, and quantitative restrictions to mitigate the local effects of STR activity. This includes the

express prohibition of STRs—or at least certain types, such as secondary property STRs—in areas

with particular zoning (e.g., in residential areas); the designation of exception zones (e.g., a main

commercial street, plaza, or particular site) in which primary use STRs are permitted; the institution

of quotas and moratoriums; and the imposition of annual night caps on entire-unit rentals (as noted

above). These rules are also set out in Table 6.

In terms of spatial rules, notable jurisdictions in our analysis are Kelowna, Montréal, Québec City,

and Whistler. In Kelowna, the Zoning Bylaw was amended to only permit STR operations as a

secondary use within a dwelling unit: that is, as secondary to the applicant using the dwelling

primarily (more than 240 days per year) as a residence. However, the Bylaw also includes an

exception for dwellings located in areas designed to accommodate higher levels of tourist activity,

such as those zoned for high-rise apartment housing and hospital and health support services, as

well as tourist commercial use (e.g., comprehensive resort developments). In such areas, it is

permissible to operate a primary use STR, though on some sites, such operations are subject to an

annual night cap, given rules that require the unit to serve as long-term accommodation (either for

a month-to-month tenant or the owner) six months per year. Similar rules exist in several Montreal

boroughs, including Ville Marie, Plateau-Mont-Royal, and Rosemont-La-Petite-Patrie, where urban

planning bylaws have been amended to restrict the operation of what are deemed “commercial

20

tourist homes” (i.e., primary use STRs or “general tourist accommodation” in the provincial

framework) such that they are not permissible, save for in select commercial districts,

5

and even

then, not within a certain distance from existing tourist homes.

6

In Québec City, commercial tourist

homes are classed as a c10 use—the same category as hotels—and each borough has established

certain areas in which this use is either authorized or a conditional use (Ville de Québec 2022).

Whistler’s Zoning and Parking Bylaw and Tourist Accommodation Registration Bylaw carry out the

objectives of the Council Policy on Tourist Accommodation, balancing the housing and quality of life

needs of local residents and workers, with the demands of a tourism-centric (and outdoor sport

driven) economy. Part of this requires maintaining ample and attractive accommodation for

tourists, athletes, and workers. As a result, land use designations strictly prohibit tourist

accommodation operations in most residential areas, limiting nearly all such operations to

designated tourist accommodation zones. There is one exception, however, which permits in select

residential zones the use of townhouses and detached residences as temporary accommodation

for 10 guests or fewer.

Very few jurisdictions in Canada impose quantitative restrictions, such as quotas and night caps, on

STR operations. Only four municipalities—Kelowna, Toronto, Québec City, and Iqaluit—have placed

limits on bookable nights, beyond the effective limits that exist in some jurisdictions as a result of

primary residence requirements. Further, when compared to international jurisdictions that also

impose such restrictions, the 180-night limits in Iqaluit and Toronto are generous, with cities such

as San Francisco and London capping the bookable nights at 90 days for entire-unit listings, and

Amsterdam limiting such bookings to 30 days (Pforr et al. 2021, 124). Banff is the only municipality

in which there is a firm STR quota, with the Banff Land Use Bylaw establishing a cap of 65 on the

number of STR licences, which are then allocated across residential districts (Schedule D).

However, other jurisdictions have found ways to introduce flexibility into quota-like approaches to

allow for adjustments in the face of emerging issues and shifting market dynamics. In Regina and

Saskatoon, for example, licensing bylaws include particular provisions for secondary property STRs

that place a moratorium on the granting of new licences if the city’s vacancy rate falls below three

per cent, and which do not allow more than 35 per cent of the dwelling units in a multi-dwelling

structure to be primary use STRs.

Development Permits and Approvals

In general, development permits are either waived or not required for STR operations across

jurisdictions in our analysis. However, in Banff, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Montréal, Québec City,

5

Commercial tourist homes are limited to Plaza St-Hubert (Rosemont-La-Petite-Patrie), parts of St-Laurent and St-Denis

(Plateau-Mont-Royal), and Ste-Catherine between St-Mathieu and Rue Atateken (Ville Marie).

6

In Ville-Marie, for example, such STRs must be 250 metres apart.

21

Ottawa, and Halifax—dependent on the zone and STR use type—STRs are, instead of being

outlawed outright, deemed a discretionary or conditional use, and thus require approval through a

development permit process prior to licensing and registration can be completed.

Banff is an outlier in our review, given the requirement that all STR operations obtain a

development permit prior to being approved for operation. This involves the applicant submitting

proof of ownership or owner consent; a property and unit description; floor and site plans; photos;

and information regarding any proposed signs. In Saskatoon, discretionary use approvals are

necessary for primary use STRs in certain zones. Here, the application requirements are similar to

those that exist in Banff. Development officers reviewing applications consider the suitability of the

proposed use in terms of conformity with the Community Plan, as well as a number of STR-specific

metrics, such as the suitability of the proposed use in the location, impact on the character of the

neighbourhood, and the cumulative impact of other discretionary uses on residential

characteristics. In Edmonton, a development permit for a major home-based business is required

for live-in hosts who wish to operate an STR with more than two sleeping units. If proposed in a

zone in which the operation is a permitted use, the application involves submitting information on

the proposed business, expected visits per week, and a site plan noting the scale of the proposed

operation. If a discretionary use, a traffic impact assessment is also required. These applications

can be denied if the use is deemed to be disruptive of residential character. Rules are similar in

Halifax for STR bedroom operations: if one wishes to offer several rooms for rent in one’s primary

residence while serving as a live-in host, one must obtain a development permit. In Montréal and

Québec City, zoning rules are implemented at the borough level, and in some cases, those wishing

to operate a primary use STR may need to obtain an occupancy permit prior to being granted a

provincial licence. In Victoria, assessments are only conducted for property owners seeking to gain

legal non-conforming status.

Finally, in Banff, Saskatoon and Edmonton some or all STR application approvals are subject to

community feedback. When submitting a development permit request related to the operation of

an STR in Banff, prospective STR operators must notify the public by posting a sign on the property

for a minimum of three weeks, and in reviewing the application, authorities may consider the

opinions of adjacent landowners. As part of the review process in Saskatoon, the Community

Services Department provides written notice of the application to owners of property within 75

metres of the subject site, as well as the local community association in the area, inviting

comments for 21 days (City of Saskatoon 2022a). In Edmonton, applicants must provide all

properties located within 60 metres of the dwelling written notification of permit approval, inviting

neighbours to raise objections to the operation.

22

TABLE 6: STR PROHIBITIONS AND RESTRICTIONS

Only permitted in

principal residence

Entire-unit STRs

prohibited

Annual cap on

bookings

Prohibited dwellings

Zoning prohibitions

Quota or moratorium

Development permit

and assessment

Kelowna

Yes

*exception: select

areas in tourist, health

zones

No

Yes: effective cap of 125

nights on entire-unit

listings in areas where

non-PR STRs prohibited

secondary suite, carriage

house, vehicle, tent,

accessory bldg, group

home, lodging house

non-PR STRs are

prohibited outside of

select areas in tourist

and health zones

No

No

Tofino

No

*note: must be on lot

with 2 dwellings, one of

which is host’s PR

No BUT resident must be

present in other dwelling

*exception (CD(EL)): can

rent townhouse to 5 guests

in absence of resident

No

dwelling with >3 sleeping

units, 2- & multi-family

dwelling, accessory

building, vehicle, tent

prohibited use in several

res. & comm. districts

No

No

Vancouver

Yes

No

No

garage, studio, SRO,

Rental 100, vehicle, unit

in prohibited buildings

registry

conditional use in most

res. (RS, RT, RM, FM),

comm.(C), historic (HA)

districts

No

exempt from

development permit

requirement

Victoria

Yes

*exception: legal non-

conforming status

Yes host must be live-in,

max 2 bdrms can be rented

*exception: entire unit can

be rented “occasionally”

No

secondary or garden

suite that is not a

principal residence

----

No

No

*exception: assessment

required legal non-

conforming status

Whistler

No

No

No

employee housing,

apartment, auxiliary unit,

detached dwelling, most

duplexes & townhouses

prohibited in res. zones

*exception (some res.

zones); townhouses can

be rented to ≤10 guests

when unoccupied

No

No

Banff

Yes

Yes: Host must be “live-in.”

Only permitted in a room,

suite, or accessory unit of

the property.

No

prohibited if not a room,

suite, or accessory unit of

a single-detached home

prohibited outside

residential districts

Quota: 65 licences across

11 districts

Proximity: New STR

cannot be within 75m of

existing

Current moratorium

Yes (all applications):

App: floor & site plan;

property, unit desc. &

photos; owner consent

Process: host notifies

public (sign); inspection;

adjacent owners notified

+ decision in newspaper.

Calgary

No

No

No

No

----

No

No

Edmonton

No

No

No

No

major home-based

business (more than 2

sleeping units & live-in

host) discretionary use in

some zones

No

Yes (live-in host & >2

sleeping units):

App: bus. description &

visits/week; site plan

[permitted use] + traffic

impact assess. [disc. use]

can be denied on basis of

disrupting character

Regina

No

No

No

temporary structure,

vehicle, recreational

trailer or structure, illegal

accessory building

permitted use in all

residential and mixed-use

zones

Quota: max 35% units in

multi-unit bldg. can have

non-PR licence

Moratorium on non-PR

licences if vacancy <3%

No

23

Only permitted in

principal residence

Entire-unit STRs

prohibited

Annual cap on

bookings

Prohibited dwellings

Zoning prohibitions

Quota or moratorium

Development permit

and assessment

Saskatoon

No

No

No

No

Non-PR STR is a

discretionary use in many

residential districts

Quota: max 35% units in

multi-unit bldg. can have

non-PR licence

Moratorium on non-PR

licences if vacancy <3%

Yes (disc. use non-PR,)

App: property info, site

plan, parking. Consider

location, character. Notify

owners within 75m

Churchill

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Niagara

OTL

No

*exception: Country

Inns, B&Bs must be in

principal residence

No

*exception: Country Inns,

B&Bs, can only be rented as

bedrooms in a principal

residence

No

non-single-detached

dwelling occupied for min

4 years *exception:

vacation apartments

must front onto public

road or Niagara Parkway;

Country Inn permitted by

site-specific zoning bylaw

amendment only

No

No

Ottawa

Yes

*exception: cottage or

Dedicated STR

(grandfathered)

No

No

vehicle, trailer, accessory

bldg, community housing,

coach house /secondary

dwelling that is not a PR

prohibited in subzones

AG4-AG8; areas where

B&B is prohibited

No

No

Toronto

Yes

No

Yes: 180-night cap on

entire-unit rentals

vehicle, accessory

dwelling that is not a PR

prohibited in some

commercial zones

No

No

Montréal

Varies by borough,

zoning, and specific

location

No

No

must be above ground

non-PR STR prohibited in

some areas in some

boroughs. cannot be

adjacent to bar, theatre,

dance hall, reception hall

Proximity: In some

boroughs, must be 150m

between non-PR STRs.

Yes: occupancy permit

required for non-PR STR

in some boroughs

Québec

City

Varies by borough,

zoning, and specific

location

No

Yes: 90-night cap on

collaborative (i.e., PR)

STRs

Non-PR STR (classed c10

–hotel) prohibited in

areas of each borough

Yes: may need permit for

some non-PR STRs,

depending on borough

Freder

-

icton

Yes

*exception: commercial

zones that permit

hotel/motel

No

*in res. zone: in single-

detached dwelling, max 3

rooms can be used for STR

No

dwelling that contains

group home, childcare

centre, home occupation

Prohibited in non-PR

dwellings in res. zones

No

No

Halifax

No

No

No

Secondary or backyard

suite if not a primary

residence

Non-PR STRs only

allowed in some zones

(commercial)

No

Yes (short-term bedroom

rental, commercial STR)

Charlotte

-

town

Yes

No

Secondary/garden suite

(if host not in principal

dwelling), apartment

Prohibited outside

residential zones [R-1L,

R-1S, R-2, R-2S, R-3, R-4]

----

No

St.

Johns

No

No

No

No

N/A

Yellow-

knife

No

No

vehicle

permitted in all

residential, commercial

mixed-use zones

----

Development permit may

be required; unclear

Iqaluit

Yes

*exception: sec.suite

accessory to host’s PR

No

Yes: 180-night cap on

entire-unit STR

No

No

No

24

4. LICENSING SYSTEMS AND OPERATIONAL AND

SAFETY STANDARDS

Registration and licensing frameworks rest on and operate according to the foundation set through

the determination of definitions, use types, and spatial and locational restrictions outlined in the

previous section. These frameworks require authorities to establish licence categories (which are

often linked to use type and/or unit characteristics), operational restrictions, requirements related

to guest management, safety, and experience, as well as a process for registration. Given the

elements of these frameworks—which can include restrictions on the number of units per dwelling

and guests per room; prohibitions of overlapping bookings; parking requirements; safety rules (e.g.,

means of egress, window and secondary lock requirements), and provisions related to advertising,

record keeping, and guest information—they draw on aspects of business licensing and zoning.

Licensing and registration serve two important management purposes. First, licensing is the first

step in supporting compliance with use restrictions, zoning, noise, and other community rules, as

well as operational standards. Second, licensing provides authorities a way to keep track of the

type and extent of STR activity that is being undertaken. This is particularly true when platforms are

also required to obtain a licence and must adhere to data sharing agreements. Gaining access to

comprehensive data on registered STRs, nights booked, income generated, and other metrics can

drive regulatory responsiveness and effectiveness, particularly if the data is used to support

ongoing efforts to adapt frameworks to be more exacting and flexible in the face of shifting market

dynamics. Table 6 outlines the components of the registration frameworks.

LICENCE TYPES

STR operators in the majority of jurisdictions in our review are subject to a licence framework, all of

which include registration requirements and various licence fees (Table 7; p. 25). In municipalities

with regulatory frameworks, authorities have either enacted STR-specific bylaws, or updated

existing business licence bylaws to reflect STR operations. Further, in five cases—Québec City,

Montréal, Halifax, Charlottetown, and St. John’s—the municipality is located in a provincial

jurisdiction with a tourist accommodation framework that oversees the licensing of all STR

operations conducted in the province, and thus has not established a separate licensing system.

7

Overall, the licence types established through these frameworks follow three approaches: broad

(i.e., a single licence category and cost); use-based (i.e., distinctions based on primary or secondary

use STR and cost); and unit-based (i.e., distinctions based on dwelling characteristics and cost).

7

However, Charlottetown intends to introduce a licensing system in the future (Department of Planning & Heritage