The Modern U.S. Reptile Industry

Ariel H. Collis, M.A.

Robert N. Fenili, PhD.

Georgetown Economic Services, LLC

Economic Analysis Group

January 5, 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

-i-

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 1

Overview of the U.S. Reptile Industry............................................................................... 1

History................................................................................................................................ 1

Reptile Laws, Regulations and Proposed New Regulations .............................................. 2

I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 3

The Reptile Narrative: John Till’s Story ............................................................................ 4

The Counter-Narrative to the John Till Story. ................................................................... 7

II. PARTICIPANTS IN THE MODERN U.S. REPTILE INDUSTRY ............................... 12

Reptile Pet Owners .......................................................................................................... 12

Reptile Suppliers .................................................................................................. 15

Reptile Breeders ................................................................................................... 16

Mass Producers .................................................................................................... 16

Morphs and Large Reptiles .................................................................................. 17

Large-scale Breeders ............................................................................................ 18

Small-scale Breeders ............................................................................................ 18

International Trade ........................................................................................................... 20

Importers .............................................................................................................. 21

Exporters .............................................................................................................. 24

Wholesalers/Distributors.................................................................................................. 27

Retailers ........................................................................................................................... 28

Pet Superstores ................................................................................................................. 28

Pet Stores ......................................................................................................................... 29

Hobbyist Retailers ............................................................................................................ 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

-ii-

Online Sellers or E-tailers ................................................................................................ 31

Summary of Retailers ...................................................................................................... 31

Ancillary Reptile Products and Services.......................................................................... 32

Manufacturers ...................................................................................................... 32

Reptile Product Distributors ............................................................................................ 34

Reptile Delivery Services ................................................................................................ 36

Reptile Veterinarians ........................................................................................... 37

Reptile Expos or Trade Shows ......................................................................................... 39

Other Reptile Organizations ................................................................................ 41

Reptile Display Organizations ............................................................................. 41

Reptile Entertainment Companies ....................................................................... 43

III. TURTLES, LIZARDS, SNAKES.................................................................................... 44

Turtles .............................................................................................................................. 45

Lizards.............................................................................................................................. 48

Snakes .............................................................................................................................. 49

Small and Docile .............................................................................................................. 49

Large Constrictors ............................................................................................................ 50

Venomous snakes................................................................................................. 51

Snake Morphs .................................................................................................................. 52

IV. CURRENT AND PROPOSED FEDERAL LAWS/REGULATIONS: THEIR

IMPACT ON THE REPTILE INDUSTRY ..................................................................... 54

The Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). ........................................................................... 55

CITIES ............................................................................................................................. 56

Impact of CITIES on the Reptile Industry ....................................................................... 58

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

-iii-

The Lacey Act .................................................................................................................. 58

Proposed Rule to List Nine Constrictors as Injurious Wildlife ....................................... 59

Impact of the Proposed Rule on Imports. ............................................................ 60

Impact of the Proposed Rule on Exports ............................................................. 62

Export substitution Under the Proposed Rule ...................................................... 64

Impact of the Proposed Rule on U.S. Reptile Businesses................................................ 65

Prices .................................................................................................................... 65

Holding Costs....................................................................................................... 66

The Economic Loss to the Reptile Industry of the Proposed Rule .................................. 67

Low-Impact Scenario ........................................................................................... 68

High-Impact Scenario .......................................................................................... 69

Long-Term Economic Loss ............................................................................................. 71

V. CONCLUSIONS.............................................................................................................. 73

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report provides an overview of the modern U.S. reptile industry. The United States

Association of Reptile Keepers (“USARK”) commissioned this report to shed light on a largely

unstudied sector of the United States economy. The report details the size, scope, and flow of

trade of the reptile industry within the United States. It concludes that the U.S. reptile industry is

vibrant and has grown rapidly, but that the industry has been and continues to be impeded by

federal legislation and regulations restricting the import, export, and domestic sale of reptiles.

Overview of the U.S. Reptile Industry

The U.S. reptile industry encompasses a vast number of participants including pet

owners, hobbyists, breeders, importers, exporters, wholesalers, pet store proprietors,

pet show promoters, entertainers, veterinarians, and manufacturers of pet food and

ancillary pet products.

In 2009 businesses that sell, provide services, and manufacture products for reptiles

earned revenues of $1.0 billion to $1.4 billion.

In 2009 4.7 million U.S. households owned 13.6 million pet reptiles. Reptile

owners are spread throughout the United States without a concentration in any one

area of the country.

Reptile businesses can be found throughout the United States although reptile

importers are more densely concentrated in Florida and California than in other

states.

The vast majority of reptile businesses are small, family-run businesses.

History

The U.S. reptile industry has experienced a significant shift toward domestic

captive breeding over the past twenty years.

Breeders transformed snake husbandry from a hobby to a viable profession by their

successful cultivation of uniquely colored snakes, called morphs.

-2-

US turtle farmers were pioneers in the global pet turtle market. U.S. turtle farmers

continue to lead the world in pet turtle production and sales.

Reptile Laws, Regulations and Proposed New Regulations

Federal and state regulations and laws concerning reptiles have negatively impacted

the reptile trade within the United States. These laws and regulations have made

selling and shipping reptiles more difficult and more costly.

A new regulatory proposal by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list nine

constrictor snakes as injurious wildlife life under the Lacey Act, however, goes

beyond simple increasing the costs of participants in the retail industry. The

proposal will limit the nearly all sales of the nine constrictors. If enacted, the

proposal has the potential to cause deep and lasting damage to the snake market--

the very sector of the reptile industry that has helped to drive its growth.

If the proposal is enacted:

In the short-term, the industry, and snake breeders and sellers in particular, will

experience significant economic losses. We estimate that revenues lost will be

between $76 million to $104 million in the first year, a loss of 5 to 7 percent of total

industry revenues.

The long-term impact of the proposal on the reptile industry will also be severe.

The economic loss to the industry over the first ten years after the proposal’s

enactment will be between $505 million to $1.2 billion in lost revenues, assuming

historical industry sales growth.

Even assuming no growth, the economic loss over the first ten years after the

proposal’s enactment will be between $372 million to $900 million in lost revenues.

-3-

I. INTRODUCTION

The modern U.S. reptile industry is young and has grown rapidly since it came of age in

the 1990s. In less than two decades, it grew from a marginal side business for a few pet stores to

a complex industry with annual revenues approaching $1.4 billion. The prime movers fueling

this growth are small, predominately American businesses.

Many of these businesses began as captive breeding operations run by reptile enthusiasts

and hobbyists. Over the years, these businesses have expanded their customer base to include

foreign pet owners. In 2009, 11.3 million live reptiles were exported from the United States,

while only 900,000 live reptiles were imported into the United States.

1

In short, U.S. small

businesses dominate the global reptile industry.

2

As the reptile businesses have grown, so too has reptile ownership. The American Pet

Products Association (“APPA”) reports that from 1994 to 2008, the number of U.S. households

that own a reptile rose from 2.8 million to 4.7 million, an increase of 68%. In contrast, the

number of households that own any kind of pet increased only 35% over that same period.

The individuals and businesses that comprise the industry have as a common feature their

wonder and appreciation of all living creatures, especially reptiles. In researching this report, we

1

United States Fish and Wildlife Agency Law Enforcement Management Information System

(“LEMIS”) data.

2

The report was commissioned by The United States Association of Reptile Keepers.

-4-

have interviewed many owners of reptile businesses.

3

We have found that their lives followed a

common narrative.

4

We have summarized this common narrative by creating the John Till story.

The Reptile Narrative: John Till’s Story

5

John Till cannot remember a time when his room was not filled with animals. He would

spend most of his spare time as a kid trolling the fields and streams that bordered his

neighborhood catching mice, frogs, garter snakes, and turtles. He hung around Selligman’s

Aquarium with his friends listening to Mr. Selligman hold court, trying to pick up tips on

feeding and reptile and amphibian care. At the age of 13, when the den had been taken over by

garter snakes and salamanders and even the guest room was filling up with turtles, John’s mother

gave him an ultimatum – if he caught something and wanted to keep it, he would have to give up

an animal in his current collection. His parents were no longer buying him any more animals.

When he complained to Mr. Selligman about his mom’s new rule, the pet store owner

laughed. If John wanted to look after animals, he was more than welcome to feed the animals,

sweep up, and clean cages at Selligman’s Aquarium. He would even be paid for his labors.

3

Information for this report was gathered through a variety of primary and secondary sources. Our

primary sources include our interactions with reptile breeders and hobbyists at two reptile expositions in

San Diego, California and Daytona, Florida, as well as interviews and surveys of a number of individuals

in the reptile trade. For more information on these surveys and survey methodology see Appendix I:

Estimation Methodology.

4

Information for this report was gathered through a variety of primary and secondary sources. Our

primary sources include our interactions with reptile breeders and hobbyists at two reptile expositions in

San Diego, California and Daytona, Florida, as well as interviews and surveys of a number of individuals

in the reptile trade. For more information on these surveys and survey methodology see Appendix I:

Estimation Methodology.

5

The following narrative is a fictionalized composite of several of the life stories of reptile

breeders operating in the United States.

-5-

By his fifteenth birthday, John was practically running Selligman’s Aquarium. And he

no longer just used nets to gather new reptiles as pets. He would import snakes and lizards from

South America and Africa. Often, his father would often drive John to the airport to inspect and

accept delivery of an insulated fifty pound box packed with neatly stacked containers. In each

container was an iguana or a baby Boa constrictor. While most kids his age were working hard

at mastering video games, John was learning import regulations.

When he was 16, John traveled with Mr. Selligman to Orlando, Florida to attend his first

reptile trade show. To John, it was a revelation. Breeders stood behind tables covered with

plastic containers filled with snakes, lizards, and turtles. All of the reptiles had such bright

colors and unique markings that they looked like works of art. Each table was thronged by

reptile enthusiasts, cash in hand. The best breeders were spoken of in reverent tones. Every

breeder was accessible and willing to trade tips and give breeding advice. That was the life John

wanted. He had found his calling. He wanted to be a snake breeder.

When he returned home, John read everything he could about snake breeding, just

waiting for the National Breeders Expo to come around again. At the next year’s show he

bought some fantastically colored baby Boa constrictors and planned his breeding with the

precision of a scientist. After four years, he sold enough snakes to recover his initial investment.

Every year after that, John’s business expanded. Pet stores, wholesalers, and other enthusiasts

(who John counted as his friends) were eager to purchase each newly patterned Boa that he bred.

Just as some people want to collect and trade Picasso paintings, John’s customers wanted snakes.

Some of his customers saw snakes as a good investment, some just wanted them for their

collections, and some wanted them to trade. John knew that a good collectible is something one

can enjoy, but could also trade if the offer is right.

-6-

It looked as if John’s business would keep growing forever. At least that is what John

thought. But in 2008 John’s snake sales came almost to a standstill. People were no longer

purchasing thousand-dollar Boas. Part of the problem was the sinking economy. Part of the

problem was that, at that time, the U.S. federal government was proposing a rule change to the

Lacey Act that would result in the ban on interstate shipments of Boa constrictors, as well as

other constrictor species.

6

The fear that these constrictors would come under the Lacey Act caused snake prices to

drop, because people were selling their snakes cheaply in anticipation of the ban going into

effect. Boa prices plunged. A Boa that a few years ago would have sold for $1000, suddenly

sold for less than $50. Sales were barely enough to cover costs. And those costs, including food,

cleaning supplies, utilities, veterinarian services continued unabated. As a result, the industry

was in contraction. John noticed that even some of his suppliers were cutting staff. John thought

of applying for a desk job and shuttering his breeding business, but he just could not do it. He

loved the snakes too much and had too much invested in his business. The government’s ban

had not been enacted yet. Until it did, he just could not give up on his calling.

* * *

While the story above focuses on one fictional breeder, it is a variation on the story of

most of the breeders in the reptile industry.

7

For example:

Ralph Davis of Ralph Davis Reptiles: “I was born in 1967 into an animal loving

family. By the time I was ten years old, I was completely hooked on reptiles. I

would go out and collect any kind of herp

8

I could find, turtles, lizards and most

6

75 FR 11808; March 12, 2010.

7

See also, mcreptiles.distortionsleep.net/about.html, royalconstrictordesigns.com/ index.php?

page=about-us; www.allboas.com/fascination.php; and www.blackpearlreptiles.com.

8

The term herp is short for herpetofauna. Herpetofauna refer to a category of animals which

includes reptiles and amphibians.

-7-

definitely snakes! My bedroom was full of tanks and makeshift containers for all

my "wild" pets. I worked off and on at the local pet shop for supplies, not money. I

would also work for animals; at the time, Savannah monitors, skinks, and ball

pythons were my favorites.

This passion for reptiles lasted into my teens and right into adulthood. I cannot

remember as a kid or a teen ever not having a room full of reptiles…and it is still

that way now!”

9

Kim Thomas of The Frog Ranch: “Founder Kim Thomas spent the majority of his

childhood growing up in the fields, streams, and ponds of California. He spent

nearly every day collecting, keeping and caring for frogs, snakes and any other

creature he was able to catch. In 1968 at the age of 12 he began his "professional"

career at a pet store feeding, watering and cleaning cages. Rising every morning at

5 a.m. in order to finish in time to get to school, his afternoons were spent

delivering newspapers and then it was off to the fields and creeks until dusk.”

10

Kathy Love of CornUtopia: “I've been interested in herps (reptiles & amphibians,

collectively) since early childhood. I grew up absorbed with all wildlife, including

early fascinations with horses, cats & dogs. Being a veterinarian was the first

career I ever dreamed of obtaining. I learned about herps through TV, visiting the

local Milwaukee Zoo and Museum of Natural History, and through books.

My first wildlife experiences were with local garter snakes, Thamnophis sirtalis,

that neighborhood kids found in wooded lots near my home and used to try to scare

me. That sure backfired on them! My initial fears quickly subsided and were

replaced by curiosity as snakes soon became pets, and later a part-time pet business

(called "Jungle Hut") in my hometown of Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA.”

11

Business owners like these, the John and Jane Tills, are responsible for the rise of the United

States reptile industry and for its transformation into the billion dollar industry that it is today.

The Counter-Narrative to the John Till Story.

Some critics believe that the reptile industry is dominated by unscrupulous individuals

who smuggle reptiles into the United States to make easy profits. These critics contend that

9

http://www.worldofballpythons.com/breeders/ralph-davis-reptiles.

10

www.thefrogranch.com/about.php.

11

http://www.cornutopia.com/corn%20utopia%20on%20the%20web/20about%20kathy%20love%2

0cornutopia%20corn%20snakes%20cornsnakes.htm.

-8-

retailers knowingly sell these illegally smuggled reptiles to owners who are desperate to own

reptiles as pets and who do not care where the reptiles come from.

12

However a review of

business and trade press about reptile smuggling provide little to substantiate this picture of the

reptile industry. The evidence shows that the amount of live reptile smuggling that takes place in

the United States is small. The handful of high-profile cases involving reptile smuggling, which

have often been repeated in the popular press, took place twenty or more years ago.

13

Breeders not smugglers form the core of the modern reptile industry. The industry was

built up by innovative, John Till-type breeders such as Bob Clark, Jesse Evans, Bob Applegate,

and Mark and Kim Bell, who have pioneered and expanded captive breeding within the United

States. This expansion has resulted in decreased reptile imports and has contributed to the fact

that there is very little reptile smuggling in America.

U.S. federal government agencies and animal rights organizations often contend that

there is an extremely large amount of wildlife and reptile smuggling worldwide and in the United

States. For example, a joint September 1998 press release by the Department of Justice (“DOJ”)

and the Department of the Interior (“DOI”) states that “According to INTERPOL, the value of

12

Bryan Christy, in his book on pre-1992 reptile smugglers, The Lizard King, takes this counter

narrative picture of reptile owners one step further. He states that “Reptile people are on a trajectory from

the time that they are children: bigger, meaner, rarer, hot.” (See Bryan Christy, The Lizard King: The True

Crimes and Passions of the World’s Greatest Reptile Smugglers, 6-7.) Christy’s view is that reptile

“people,” after becoming accustomed to small and safe reptiles, soon crave bigger and meaner reptiles.

Their cravings lead them rarer reptiles, and, finally, they must have hot (meaning venomous) reptiles. In

short, turtles and corn snakes are nothing more than the gateway drugs leading owners to collect rare

albino reticulated pythons, and then to seek out highly rare, mean, and venomous snakes such as albino

cobras and mambas.

If Christy were to be believed, a significant number of the 2.8 million households that owned

reptiles in 1994 for example, would now be cobra and mamba owners as they progress along Christy’s

bigger, meaner, and hot continuum. In fact, the number of “mean and hot” snakes owned by Americans is

insignificant. In short, Christy’s thesis is not supported by facts.

13

See Bryan Christy. The Lizard King.

-9-

illegally traded wildlife is approximately $6 billion annually”

14

and that “Reptile smuggling is a

high-profit criminal enterprise, and the United States is its largest market.”

15

This lurid description of the reptile industry is not supported by facts. When Bill Clark,

an Interpol Secretary was interviewed about the basis for Interpol’s wildlife smuggling estimates,

he said, “We have no idea where the media gets its numbers, but it's not from Interpol.…

Interpol has no reliable data on which to base an estimate.”

16

Clark’s comments comport with

the statements of Peter Younger, director of Interpol’s wildlife crime division. Younger states

that, for wildlife smuggling, “Our best guess is anything from 10 to 15 percent of the lawful

trade … but it’s only an educated guess.”

17

Based on Interpol’s educated guesses, illegal wildlife

trade worldwide is $1 to $3 billion, a figure which is significantly lower than the figures quoted

by U.S. government officials.

14

“DOJ, DOI Announce Arrest of Renowned Reptile Smuggler,” September 15, 1998. The DOJ

repeats the $6 billion wildlife smuggling claim in an 2000 press release, “Reptile Smuggler Extradited to

the United States from Mexico,” U.S. Department of Justice August 23, 2000.

In 2008, the Congressional Research Service made the claim that “Global trade in illegal wildlife is a

growing illicit economy, estimated to be worth at least $5 billion and potentially in excess of $20 billion

annually.” However, the paper concedes that "the illegal trade is difficult to quantify with any accuracy."

See Sheikh, Pervaze A. and Liana Sun Wyler. “International Illegal Trade in Wildlife: Threats and U.S.

Policy,” Congressional Research Service, Updated August 22, 2008.

15

“DOJ, DOI Announce Arrest of Renowned Reptile Smuggler.” See also U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service, “Probe of International Reptile Trade Ends with Key Arrests,” September 15, 1998. The Service

states in this release that, “Reptiles have become increasingly popular as pets and as high-priced live

collectables. Collectors and breeders are enticed by the lure of the exotic, making rare reptile species an

extremely profitable black-market commodity.”

Similarly, in 2007, Joseph O. Johns, the Chief of the Environmental Crimes section in the United States

attorney’s office in Los Angeles stated that “Wildlife smuggling is the nation’s second-largest black

market, just behind narcotics, accounting for $8 billion to $10 billion a year in sales.” Jennifer Steinhauer,

“Wildlife Smugglers Test Their Skills, Even at the Airport,” New York Times, April 6, 2007.

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/06/us/06wildlife.html.

16

Bryan, Christy, “Wildlife Smuggling: Why Does Wildlife Crime Suck,” The Huffington Post,

Updated March, 18, 2010 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/01/04/wildlife-smuggling-why-do_n_

410269.html.

17

http://www.america.gov/st/energy-english/2008/June/20080616142333 mlenuhre t0. 8286859.

html.

-10-

Evidence indicates that only a small fraction of wildlife smuggling takes place in the

United States. An even smaller fraction involves smuggling of reptiles into the United States.

An analysis of smuggling in the United States was conducted by the U.S. Department of

Agriculture’s Economic Research Service using wildlife trade data for the years 2000-2004.

18

The USDA report states: “based on fragmentary inspection of the data, wildlife smuggling

accounts for approximately 1 percent of commercial wildlife shipments to the United States.”

19

According to the report, total earnings from wildlife smuggling in United States amounted to

about $17 million per year for the five-year period, 2000-2004. The report does not disaggregate

the value of shipments by wildlife type, but it does suggest that reptile smuggling is a very minor

proportion of the $17 million. It also suggests that reptile smuggling primarily involves shoes

and leather products, not live reptiles.

20

From another perspective, if reptile smuggling were so prevalent in the United States, one

would expect to see numerous accounts of law enforcement activity involving the illegal trade.

There are few such accounts. In fact, a review of the Service’s enforcement records for 2006-

2010 list only four cases involving smuggling of reptiles. They are:

A reptile smuggler based in Washington State was sent to prison for two years for the

unlawful importation of more than 230 reptiles from Thailand; the shipments, valued at

over $30,000, entered the United States in falsely labeled express mail packages.

18

The study was based on an internal U.S. Fish and Wildlife report titled “Illegal Wildlife Trade.”

19

Peyton Ferrier, “The Economics of Agricultural and Wildlife Smuggling,” United States Dept. of

Agriculture, Economic Research Service, no. 81, Note: Ferrier states that the November 2005 U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service internal report reports that : “. . . though enforcement personnel know a great deal

about what illegal trade activities occur locally, there is less understanding of illegal trade activity

nationally. . . .”

20

Even if one assumes that the USDA estimate is off by a factor of 10, i.e., the USDA understates

wildlife smuggling by 90%, even that suggests that total wildlife smuggling into the United States would

amount to less than $200 million. Even this upper bound estimate hardly supports the oft-heard statement

that the illegal wildlife trade is second in size to only the illegal drug trade.

-11-

A Virginia man who pleaded guilty to illegally importing CITES-listed tortoises was fined

$15,000.

A California man was convicted for his role in an international conspiracy to smuggle

wild-caught protected Burmese and Indian star tortoises from Singapore for distribution

in the United States.

A cooperative U.S./Canadian undercover investigation exposed the smuggling of

protected reptiles from Canada to dealers and collectors in the United States.

21

The lack of public record of enforcement suggests that reptile smuggling occurs relatively rarely

in the United States.

There is no doubt that some reptiles were and still are smuggled into the United States.

Any product that is deemed illegal to import will be smuggled into the country if potential

customers of the illegal product are willing to pay the costs necessary to induce someone to

smuggle the product into the country. This is true for any product, be it lumber, caviar, or

reptiles. However, the evidence suggests that smuggling is not a cornerstone of the reptile

industry as claimed.

In addition, over time, the federal government has expanded the list of animals, including

reptiles, that have restrictions placed on their import into the United States both by law and by

regulation. As more wildlife is added to the restricted list, economic theory predicts that, ceteris

paribus, the amount of smuggling will increase. On the other hand, economic theory also

predicts that as the production of domestic captive-born reptile increases, with concomitant

decreases in reptile prices, ceteris paribus, the benefits from smuggling illegally wild-caught

reptiles decrease and the number of reptiles smuggled will also decrease. It appears as if the

expansion of captive reptile breeding in the United States has helped to crowd out smuggling.

21

“Wildlife Trafficking Investigations 2006-2010 Highlights.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,

Office of Law Enforcement, p. 3.

-12-

The past two decades have witnessed a tremendous growth in the number and variety of

reptiles bred in captivity in the United States. Indeed, captive breeding operations form the

foundation of the modern U.S. reptile industry. These businesses have added jobs and have

contributed revenues to the overall U.S. economy. It is likely that their success has also led to a

significant decrease in reptile smuggling, as well as a decrease in the incentives to smuggle

reptiles.

II. PARTICIPANTS IN THE MODERN U.S. REPTILE INDUSTRY

The U.S. reptile industry encompasses a vast number of participants including pet

owners, hobbyists, breeders, importers, exporters, wholesalers, pet store proprietors, pet show

promoters, entertainers, veterinarians, and manufacturers of pet food and ancillary pet products.

Below, we describe some of these participants and the roles they play in the industry.

Reptile Pet Owners

According to the APPA, approximately 4.7 million U.S. households owned 13.6 million

reptiles in 2010.

22

While reptile ownership has dipped slightly in the last two years from its peak

of 4.8 million households in 2008, reptile ownership is still at its second highest level since 1994,

the year that APPA began surveying households about reptile ownership.

23

Based on our

interviews with industry members, it is widely believed that when the economy recovers, reptile

ownership will once again be on the rise.

22

2009/2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey (Hereafter “2010 APPA Study”). American Pet

Products Association. p. 453.

23

Id.

-13-

Demographically, reptile owners tend to be younger and have higher household incomes

than the U.S. population as a whole.

24

Reptile owners are spread throughout the country,,

without a concentration in any one region.

25

They are just as likely as the rest of the U.S.

population to live in big cities, rural areas, or small towns.

26

APPA estimates that in 2010, reptile owners purchased nearly $1.7 billion worth of

ancillary products and services used for the care of reptiles.

27

Table 2.1 shows that turtle owners

alone spent $765 million.

TABLE 2.1

Total Consumer Reptile Product and Service Expenditure, 2010

Reptile Type

Percentage of

Households*

Number of

Households

Average Gross

Expenditure Per

Household ($)

Total Gross Expenditure

For Reptile Type ($)

Iguana

9

423,000

517

218,691,000

Lizard (other)

17

799,000

511

408,289,000

Turtle

59

2,773,000

276

765,348,000

Snake

18

846,000

313

264,798,000

Other

5

235,000

5

19,975,000

Total

100

4,700,000

357

1,677,101,000

*Percent of households will not add up to 100% because some household own more than one type of reptile.

Source: 2010 APPA Study data.

Based on our interviews and discussions with industry participants, there are roughly

three categories of reptile owners (in order of the number of owners in each category):

24

Id.

25

2010 APPA Survey, p. 499.

26

Id.

27

We believe APPA’s $1.7 billion estimate of consumer spending on reptiles includes spending on

products which can be used for both reptiles and humans, such as paper towels and Windex. For an

estimate of total revenues from businesses that offer services and manufacture products specifically for

reptiles. See Table 2.16.

-14-

First-time owners and novices, who tend to buy only a few small, less expensive, and

easily manageable reptiles, such as turtles, corn snakes, geckos, and bearded dragons.

28

Novice

owners are often children who do not have a good deal of experience owning a reptile.

However, many novices have what some refer to as a wonder about nature, and become reptile

enthusiasts

.

29

Enthusiasts, who are distinguished by the depth of their interest and knowledge about

reptiles and reptile care. Spending on reptile products and medical care among enthusiasts is

around four times greater than the average reptile owner.

30

While the number of reptiles that

each enthusiast owns varies greatly, what binds them is their love of reptiles. In addition, they

take an active interest in what we refer to as reptile culture. That is, they attend reptile shows,

read reptile publications, and join reptile and amphibian societies. Enthusiasts tend to own not

only more reptiles than novices, but the reptiles they collect are more exotic and more

spectacular (in terms of morphology and coloration) than those of novices.

31

Hobbyists, or part-time breeders, are reptile owners that actively engage in breeding

reptiles. Hobbyists study the genetics of reptiles so that they can plan to breed their animals to

achieve certain body types and colorations. Almost every hobbyist sells (or intends to sell) at

28

Personal communication with a leading reptile retailer.

29

Personal communication with a leading reptile retailer.

30

Reptiles Magazine, a publication for reptile enthusiasts, reports in its 2010 reader survey that its

average reader spends $1500 per year on “supplies, medical care, and other necessary items for [a]

reptile.” This is roughly 4.5 times the household weighted average spending reported for all reptile

owners in the APPA 2010 study, $330.

31

Personal communication with a leading reptile retailer.

-15-

least some of his or her collection. Many part-time breeders will sell the reptiles they have bred

at local reptile shows. It is estimated that there ate 8,000 to 10,000 reptile owners in this group.

32

The novice, enthusiast, and hobbyist classifications are fluid. A novice may bond with

her pet and develop a more active interest in reptiles and become a reptile enthusiast. Some

enthusiasts may start to breed and sell some of their captive bred reptiles, albeit on a small scale.

Indeed, a particularly successful part-time breeder may decide to try to breed reptiles full-time

and become a professional reptile breeder.

Reptile Suppliers

Typically, reptiles are either captive bred domestically or imported from other countries.

An imported reptile is typically wild-caught but it can also be captive bred. A reptile may pass

through many hands before it reaches its final owner. We attempt to describe components of the

reptile supply chain, but caution that, realistically, supply chains are more complicated than our

simplified descriptions. One company may provide the services that we describe as two separate

links in the supply chain, such as breeders who also import. Similarly, when we categorize total

revenues for a particular business, we ascribe all revenues from that business to the primary

function of that business. For example, if a business primarily engages in breeding, but also

exports, we ascribe all revenues that the business earns from breeding and exporting to breeders.

32

Personal communication with leading reptile retailers and manufacturers.

-16-

Reptile Breeders

An increasing number if reptiles that are purchased by pet owners, hobbyists, and private

collectors come from U.S. reptile breeders. We classify reptile breeders based on the scale of

their operations and the type of reptiles they breed.

Mass Producers

The largest breeders, both by average volume of production and average yearly gross

receipts, gear their production toward the pet store trade with a focus on novice to intermediate

pet owners. Thus, these breeders primarily produce reptiles that are meant to be cared for by a

beginning to slightly experienced (i.e., intermediate) owner. Reptiles they breed include turtles,

geckos, common iguanas, bearded dragons, milk snakes, corn snakes, non-morph ball pythons,

and non-morph Boa constrictors.

33

We refer to these breeders as “Mass Producers” because they

sell large quantities of reptiles through supply agreements, typically to pet store chains. Reptiles

bred by Mass Producers that are not sold directly to pet stores, are sold to retail distributors.

34

Mass Producers sell very little of their stock directly to households, either via the internet or at

expos or trade shows.

Mass Producers tend to have a relatively large number of employees, 20 to 30 on

average, and operate large breeding facilities. Because the reptiles that Mass Producers sell are

on the low end of the reptile price spectrum, profit margins in these businesses tend also to be

low. While churn is high among breeders generally, larger breeding businesses tend to be long

lived. There are roughly six to twelve mass producers operating in the United States.

33

Based on responses to Major Business Survey and Small Business Survey. Eugene Bessette, a

well-know breeder, refers to these reptiles as “small, safe and innocuous.”

34

Based on responses to Major Business Survey and Small Business Survey.

-17-

Morphs and Large Reptiles

Aside from Mass Producers, breeders tend to focus on reptiles that can be cared for by a

first-time to intermediate owners but have a rare scale coloration of body type, and thus are much

more expensive than reptiles sold by Mass Producers. There reptile rarities are often referred to

as designer reptiles, or more commonly, as morphs. In general, the price of a morph is positively

related to the distinctiveness of the reptile’s color and the rarity of the morph. Most sales of

morphs are to other breeders (both domestic and foreign), hobbyists, and enthusiasts. Only a

small percentage of the sales of morphs are to general pet owners.

35

Breeding morphs requires an investment in parents who have a genetic composition that

enables some of their offspring to have distinctive colors. In much the same way that a race

horse’s value depends on its ability to pass on its desirable racing genes to its offspring, a reptile

with a desirable skin pattern is valuable not only because of its skin pattern or the rarity of that

pattern, but also because that reptile can be use to bred more morphs. Morph breeders (or those

seeking to be morph breeders) will pay significant amounts (in excess of $20,000) for a rare

morph that can be added to his or her breeding stable.

A smaller group of breeder produce large and venomous reptiles. These reptiles require a

high level of expertise to safely and properly care for them. These reptiles include, but are not

limited to reticulated pythons, anacondas, Burmese pythons, and large lizards, such as monitor

lizards. This would also include venomous (or “hot”) reptiles.

Mass producers generally do not breed morphs, large, or venomous reptiles, since their

customers are interested in selling reptiles to first-time and intermediate reptile owners. First

time customers are generally not interested in large and hot reptiles, and thus, general pet stores

35

Based on interviews with reptile breeders.

-18-

also stay away from these reptiles. While some morphed reptiles, such as ball pythons, can be

taken care of by a first-time to intermediate owner, general pet stores do not want to hold

inventories of these high-priced morphed reptiles – but these stores will sell ball pythons of the

non-morphed variety.

We classify those who bred large, rare, or venomous reptiles on the basis of the scale of

their operations.

Large-scale Breeders

Large-scale breeders generally focus on producing morphs. They pride themselves on

the depth of their knowledge of reptile husbandry and genetics. Because each new morph they

produce has the potential to bring in high prices, these breeders invest in advanced animal

obstetric equipment, such as veterinary ultrasound machines, to ensure the safety of each

delivery. The number of employees working for these breeders varies widely, with some

breeders managing large collections of reptiles without assistance, while other large-scale

breeders employ up to seven full-time helpers. There are roughly eight to twelve large-scale

breeders operating in the United States.

Small-scale Breeders

Another group of breeders also attempts to produce new morphs, but these breeders

operate on a smaller scale. These “small-scale” breeders do not have the scale of production to

consistently hit the jackpot of the genetic lottery. Therefore, they focus their production on

morphs that have already been produced but are still relatively rare, using breeding stock that

typically have been purchased from large scale breeders.

-19-

While the majority of small-scale breeders focus on morphs, a small subset of them breed

large reptile species, like Burmese and reticulated pythons. Only a few businesses breed

venomous lizards and reptiles.

Most of the small-scale breeders have space outside of their homes dedicated to breeding.

They typically employ one or two employees to assist them. There are roughly 100 to 200 small

scale breeders operating in the United States.

Hobbyists and Part-Time Breeders

Part-time breeders operate at the smallest scale among breeders. Breeding is a side

project for most of these operations. They are typically one-person businesses, operated on a

part-time basis. Sales of reptiles serve mostly to supplement their income. While some

hobbyists have dedicated breeding facilities, the majority breed in their garage or basement. For

many hobbyists, sales are made more to pay for supplies for their own reptiles, rather than to

make a living. It is estimated that there are 8,000 to 10,000 hobbyists in the United States.

36

The vast majority of breeders are small businesses both by legal definition

37

and in a

generally understood sense. Of the breeding businesses that we have interviewed, nearly all of

them are family run. Some businesses are in their second generation of family ownership.

The number of breeders operating within the United States has grown dramatically in

recent years. The largest growth among breeders has taken place in the hobbyist category.

38

The

36

Based on interviews with reptile breeders.

37

Reptile breeders are classified under the NAICS code 112990, “All Other Animal Production”

NAICS Association, http://www.naics.com/censusfiles/ND112990.HTM#N112990 (Accessed

November 11, 2010).

The Small Business Administration defines a business of this category as small if they have annual sales

of less than $750,000. “U.S. Small Business Administration Table of Small Business Size Standards

Matched to North American Industry Classification System Codes.” U.S. Small Business

Administration, effective August 22, 2008.

-20-

economic downturn and increasingly restrictive laws regulating U.S. reptile sales have led many

breeders to look overseas for new customers. Many breeders also report a growing trend of

bypassing pets stores and selling directly to consumers over the internet.

We estimate that the 8,000 to 10,000 businesses that primarily engage in breeding earn

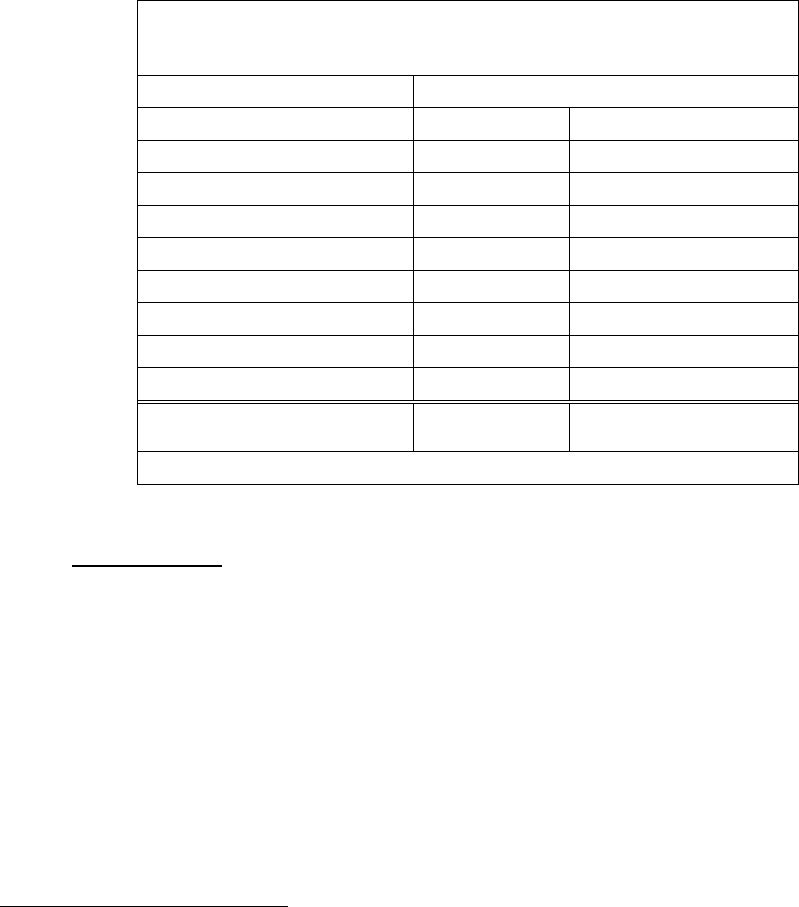

between $142 million and $183 million in revenues per year. (See Table 2.2.)

TABLE 2.2

Summary of 2009 Annual Revenues For U.S. Reptile Breeders

Breeder Category

Number of

Businesses

(Low)

Number of

Businesses

(High)

Total Annual

Revenue

Low Estimate

(Million $)

Total Annual

Revenue

High Estimate

(Million $)

Part-Time Breeders

8,000

10,000

91.2

114.0

Small Scale Breeders

100

200

18.2

33.7

Large Scale Breeders

8

12

5.2

7.3

Mass Producers

6

12

27.1

29.3

Grand Total

8,114

10,224

141.7

183.3

Source: GES analysis based on Major Business Survey and Small Businesses Survey.

International Trade

All imports and exports must enter or exit the United States from18 ports that have been

designated to handle all shipments of wildlife, including reptiles.

39

Containers for import and

export must be inspected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“Service”). Fees for these

inspections are payable by the shipper. In addition, the United States Department of Customs

38

Based on communications with breeders and show promoters.

39

These ports are located in Anchorage, Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Dallas/Ft. Worth;

Houston, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Louisville, Memphis, Miami, New Orleans, New York, Newark,

Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle. “Bringing Wildlife Into the United States.” United States

Department of Customs and Border Protection.

-21-

and Border Protection requires that importers and exporters fill out a declaration for the animals

that they wish to ship.

40

Importers

According to data collected by the Service, at least 6.9 million live reptiles were legally

imported into the United States between 2005 and 2010.

41

However, imports of reptiles into the

United States have steadily declined from 1.5 million reptiles imported in 2005 to 900,000

reptiles imported in 2009. (See Table 2.3 below.)

TABLE 2.3

U.S. Imports of Reptiles 2005-2010

Year

Number of

Reptiles Imported

2005

1,499,547

2006

1,441,135

2007

1,339,816

2008

1,146,570

2009

900,677

2010

572,158

Total

6,899,903

* 2010 is estimated

Source: LEMIS data

Table 2.4 shows that 83% of all imported reptiles entered the United States through either

Miami or Los Angeles.

42

Indeed over half of all reptiles that entered the United States from

abroad in the 2005-2010 period entered through Miami.

43

40

Id.

41

LEMIS data on live reptile imports into and exports from the United States from January 2005 to

May 2010. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Law Enforcement, produced July 16, 2010.

LEMIS data are used because it has been noted that “LEMIS data is the only detailed official record of

the legal domestic reptile trade.” Robert Reed. “An Ecological Risk Assessment of Nonnative Boas and

Pythons As Potentially Invasive Species in the United States,” Risk Analysis, Volume 25, No. 3, 2005, p

756.

42

LEMIS data.

-22-

TABLE 2.4

Top Ten U.S. Ports of Import

2005 – Jan. 30, 2010

Port

Number of

Reptiles

Imported

Percent of All U.S

Imports

Miami

3,486,765

50.53

Los Angeles

2,268,501

32.88

Dallas/Fort Worth

434,898

6.30

New York

409,867

5.94

New Orleans

121,685

1.76

Baltimore

64,425

0.93

Houston

20,210

0.29

San Francisco

18,735

0.27

Denver

12,819

0.19

Detroit

12,135

0.18

Top Ten Total

6,850,040

99.28

Source: LEMIS data

The majority of reptiles that are imported are sold either directly to pet stores or to

distributors and wholesalers who then sell the animals to pet stores.

44

Because of this pet shop

focus, the most popularly imported animals tend to be reptiles that make good pets for novice to

intermediate pet owners. The most commonly imported reptiles are Common Iguanas, Leaf-toed

Geckos, Asian Grass Lizards, Oriental Water Dragons, and Ball Pythons.

45

Table 2.5 below

shows the most-imported reptiles (by number) in 2009. These reptiles are generally much lower-

priced than reptiles that are exported. Exports are more often rare and expensive morphs.

43

The dominance of the ports of Miami and Los Angeles reflects the fact that the majority of all

importers are located in Florida or California.

44

Based on survey responses from the Major Business Survey. Companies surveyed imported

42.5% of all live reptiles from 2005 to 2009.

45

Based on GES analysis of LEMIS data.

-23-

TABLE 2.5

Top Ten Imported Reptiles, 2009

Reptile Type

Number of

Reptiles Imported

Common Iguana

113,052

Leaf-Toed Gecko

71,324

Asian Grass Lizard

71,128

Oriental Water Dragon

68,792

Ball Python

65,028

Turtle (Sp.)

39,158

Inland Bearded Dragon

28,756

Northern Savanna Monitor

22,432

Red-Eared Slider

22,069

Tokay Gecko

18,985

Top Ten Total

520,724

Source: LEMIS data.

Ten firms accounted for 72.3% of the number of reptiles imported into the United States

in 2009. The most frequently imported reptiles by these ten firms are also the Common Iguana,

the Leaf-Toed Gecko, Asian Grass Lizard, Oriental Water Dragon and the Ball Python. (See

Table 2.6)

TABLE 2.6

Top Ten U.S. Importers of Live Reptiles in 2009

Company

Number of

Shipments

Imported

Number of

Reptiles Imported

% of Total

Reptiles

Imports

L. A. Reptile Inc.

847

156,540

17.4

Strictly Reptiles, Inc.

522

90,776

10.1

The Reptile Farm, Inc.

67

79,125

8.8

Two Amigos Import & Export, Inc.

663

78,476

8.7

U.S. Global Exotics, Inc.

403

75,023

8.3

California Zoological Supply

191

55,403

6.2

Emerald Coral & Reptile

179

39,360

4.4

Lasco

41

29,681

3.3

Bushmaster Reptiles

573

24,339

2.7

Dayrich Trading, Inc.

34

22,366

2.5

Top Ten Total

3,520

651,089

72.3

Source: LEMIS data

-24-

Exporters

According to LEMIS, 69 million live reptiles have been exported from the United States

between 2005 and 2010. In contrast to imports, which have been declining steadily over the

past 5 years, reptile exports increased each year from 2005 to 2007. (See Table 2.7)

TABLE 2.7

U.S. Exports of Reptiles

2005 – 2010

Year

Number of Reptiles

Exported

2005

10,035,749

2006

14,509,230

2007

18,764,290

2008

12,573,564

2009

11,290,591

2010

2,309,600

Total

69,483,024

Source: LEMIS data

Turtles dominate reptile exports. More than 95% of all reptile exports from 2005 to

2010

46

were turtles, tortoises, or terrapins.

47

The high percentage of turtle exports is a byproduct

of a 1975 regulation imposed by the FDA which ban turtles with shell lengths under 4 inches

from being sold or transported within the United States. The regulation makes an exception to

the commercial inter-state transport ban if the turtles are destined for export.

48

46

Based on GES analysis of USFWS LEMIS records.

47

We will refer to turtles, tortoises, or terrapins collectively as turtles.

48

21 CFR 1240.62.

-25-

Before the inter-state commerce ban, turtle farmers had produced up to 15 million turtle

hatchlings for sale in U.S. pet stores. Around 5% of U.S. households had turtles as pets.

49

In the

turtle ban’s aftermath, turtle farmers diverted all of their sales overseas. Hong Kong, Mexico,

and China have become top destinations for turtles, and therefore the top destinations for all

reptile exports. However, most turtles exported to Hong Kong and China are bought as food

rather than as pets.

50

Most exports leave the United States from the port of New Orleans because most turtles

are bred in Louisiana.

51

Table 2.8 shows the top ten U.S. ports of export in 2009. It also shows

that New Orleans and Los Angeles handle over 90 percent of reptile exports.

TABLE 2.8

Top Ten U.S. Ports of Export, 2005 – 2010

Port

Number of

Reptiles

Exported

Percent of

Reptile Exports

New Orleans

55,225,244

79.37

Los Angeles

7,694,033

11.06

San Francisco

1,923,548

2.76

Miami

1,712,113

2.46

Dallas/Fort Worth

1,691,720

2.43

Atlanta

581,556

0.84

Honolulu

300,269

0.43

Houston

200,810

0.29

Minneapolis./St. Paul

143,190

0.21

Chicago

34,139

0.05

Top Ten Total

69,406,622

99.89

Source: LEMIS data

49

“Risky Shell Game: Pet Turtles Can Infect Kids,” FDA Consumer, Dec-Jan, 1987, Chris W.

Lecos. http://www.highbeam.com/eoc/1g1-6245151.ytml (Accessed November 11, 2010).

50

LEMIS data does not distinguish whether live turtles are purchased for food or as pets, but

interviews with producers indicate that Chinese and Hong Kong customers buy turtles as food.

51

“Turtle Profile,” C. Greg Lutz, Pramod Sambidi, and R. Wess Harrison, Louisiana University

Agricultural Center, p 1. See also Chapter 3: Turtles and Lizards. www.agmrc.com/ comodities__

products/aquaculture/Turtle_profile.cfm, (Accessed 8/12/2010).

-26-

As of 2009, seven of the United States’ top ten reptile exporters were located in

Louisiana. Turtle exports have declined from 2008 to 2010. Some reasons posited for this

decline include the general economic downturn, increasing self sufficiency of Chinese reptile

breeders, and hurricanes hitting the gulf coast.

52

Table 2.9 shows that, similar to the import

sector, a small number of companies export the majority of all reptiles. The top ten exporters (by

number of reptiles), all of whom are believed to be turtle exporters, exported 68% of the reptiles.

TABLE 2.9

Top Ten U.S. Exporters, 2009

Company

Number of

Shipments

Exported

Number of

Reptiles

Exported

Percent of

Total

Exports

Turtle Connection, LLC*

23

2,557,610

22.5

Concordia Turtle Farms*

91

1,013,695

8.9

Assumption Turtle Farms*

147

758,992

6.7

AC International Export, Inc.*

29

700,129

6.1

Tangi Turtle Farm*

176

669,947

5.9

Global Aquatic Consulting

122

534,981

4.7

Boudreaux's Turtle Farm, Inc.*

106

445,868

3.9

Strange Brother's Turtle Farms*

75

411,400

3.6

Wei Nuo Import & Export Corp

7

341,104

3.0

Interwell, Inc.

8

317,506

2.8

Top Ten Total

784

7,751,232

68.0

* Located in Louisiana

Source: LEMIS data

We estimate that there are 30 to 50 businesses who primarily engage in importing or

exporting reptiles. These businesses earned between $28 and $30 million in 2009.

52

“Turtle Profile,” C. Greg Lutz, Pramod Sambidi, and R. Wess Harrison, Louisiana University

Agricultural Center, p. 1 www.agmrc.com/comodities__products/aquaculture/ Turtle_profile.cfm,

Accessed 8/12/2010.

-27-

Wholesalers/Distributors

Reptile wholesalers and distributors purchase reptiles from importers, breeders, and other

distributors to sell to pet stores, zoos, and educational institutions. Most distributors also import

reptiles. Traditionally, breeders and importers did not have the staff to make and maintain

contacts with the large network of pet stores needed to sell out their stock. This intermediary

function was served by distributors. However, the number of distributors has been decreasing in

recent years because breeders are increasingly bypassing distributors and selling directly to pet

stores and individual customers through reptile shows and the internet.

53

In addition, the mass

producer breeders who supply PETCO and PETsMART with reptiles have come to provide

wholesaling services for these superstore chains.

54

Most of the distributors of reptiles are located in Florida and California.

55

These

locations allow them to be close to a large number of breeders and importers. It also allows them

to be in close proximity to ports for exporting reptiles. Wholesalers outside of major port cities

have to branch out into other parts of the pet industry. This means that, in Des Moines or

Denver, for example, wholesalers/distributors may also distribute bird supplies and frozen

rodents in addition to reptiles. These distributors may also sell animals through store front retail

locations to supplement their income.

56

There are 50 to 70 businesses that primarily engage in wholesaling and distributing

reptiles in the United States. These businesses earned $17 million to $22 million in 2009.

53

Personal communication with breeders, importers, and show promoters.

54

See the Reptile Breeders and Retailers sections of Chapter 2 for more information on the

relationship between large breeders and pet superstores..

55

Personal communication with breeders and importers.

56

Based on personal communication with leading importer, Christine Roscher, owner of L.A.

Reptile, Inc.

-28-

Retailers

Despite the growing number of sales from breeders directly to pet owners through the

internet and at local reptile shows, most pet owners purchase their animals through retailers.

57

Approximately 3,000 to 4,000 businesses sell reptiles or reptile products at over 5,000 to 6,000

locations.

58

As reptiles gain in popularity as pets, the numbers of retailers that sell reptiles will

continue to grow.

Among retailers, sales of reptile products exceed sales of reptiles.

59

This is true because

every reptile a) needs an array of products to keep it healthy, and b) requires continual purchases

of food, cleaning supplies, and nutritional supplements.

Retailers can be classified into four types: superstores, pet stores, hobbyist shops, and

online sellers (also know as “e-tailers”).

Pet Superstores

These “big-box” operations grab the biggest share of retail sales on a per store basis.

There are two national superstore chains, PETCO and PETsMART, that sell reptiles and reptile

supplies. PETCO and PETsMART each have over 1,000 retail stores located across the United

States. Superstore chains cater almost exclusively to novice and intermediate pet owners,

limiting the reptiles they sell to “small and innocuous”

60

reptiles, such as turtles, bearded

57

APPA 2010, p. 463.

58

Personal communication with reptile retailers and product manufacturers.

59

PPN, p. 9. Note that PPN’s survey results were confirmed by Major Business Survey and Small

Business Survey responses.

60

Eugene Bessette, a well-know breeder, refers to these reptiles as “small, safe and innocuous.”

-29-

dragons, geckos, common iguanas, Boa constrictors, and ball pythons. They also carry a full line

of products used in the care of reptiles.

Superstores purchase the majority of their reptiles and products from a handful of large

breeders and product manufacturers to ensure consistent quantity, quality, and regularity of their

supply. Large breeders both produce reptiles for superstores and also import and distribute

reptiles and reptile foods from other smaller companies to the superstores.

61

Similarly, large

producers manufacture products for the superstores at their own facilities as well as import and

distribute the products of smaller manufacturers to the superstores. The reliance on bigger

breeders and manufacturers serves to simplify the reptile supply chain for the superstores.

62

We

estimate that superstores earned $19 to $23 million in revenues from sales of reptiles and

ancillary products in 2009.

Pet Stores

The next largest category of retailer is pet stores. These pet stores include regional chains

and local, one or two store, “mom and pop” pet shops. While no individual store or chain rivals

PETsMART or PETCO in sales, as a group these stores sell more pet reptiles and ancillary

reptile products than the superstores.

63

These retailers are also influential as leading sources of

information about pets and pet products.

64

The vast majority of pet store sales are to customers

in the communities in which these stores are located.

61

Personal communications with reptile breeders.

62

Personal communications with reptile breeders.

63

APPA 2010, pps. 463, 469, and 479. This information was confirmed by personal

communication with retailers.

64

APPA, p. 481.

-30-

Pet stores can be further broken down into two categories: reptile specialty stores and

general pet stores.

65

Reptile specialty stores sell mostly reptiles and products for reptiles,

though many of these stores also carry amphibians, insects, and related products. Prominent

reptile specialty stores include Exotic Pets in Nevada, East Bay Vivarium in California, and Zoo

Creatures in New Hampshire.

Typically, reptiles and ancillary reptile products are a small fraction of total sales at a

general pet store. Among the general pet stores that we surveyed, reptile and reptile product

sales made up only five to eight percent of the stores’ gross yearly sales revenues. Some

examples of general pet stores that sell reptiles include: Petland, a regional pet store chain, Red

Crest Pet Shop of Texas, and Today’s Pet in Maryland.

There are an estimated 1,100 and 1,500 pet stores. These pet stores earned between $163

million to $215 million in 2009.

Hobbyist Retailers

The smallest retailer both in store size and in annual revenues is the hobbyist retailer,

who typically sells reptiles from his or her garage or basement. These retailers concentrate

almost exclusively on live reptiles, and offer little or no ancillary products. Many hobbyist

retailers specialize in a few types of reptiles, often concentrating on morphs. These home and

garage sellers are typically hobbyists moving up the supply chain.

There are an estimated 600 to 800 hobbyist retailers. These retailers earned between $15

million and $19.5 million in 2009.

65

The exact breakdown of specialty stores to general stores is unknown.

-31-

Online Sellers or E-tailers

There is a growing segment of retailers that conduct most of their business online. Some

e-tailers started out as mail-order catalogue businesses. Others used to conduct their business by

fax but are operate using email and a website. Only a few of these businesses also have

storefronts. While a small group of reptile e-tailers sell only reptiles, the majority of sales made

by online reptile stores are of ancillary reptile products. Selling online allows e-tailers to serve a

national customer base. Prominent e-tailers include LLL Reptile and Supply, The Bean Farm,

and Herpsupplies.com. There are an estimated 1,200 to 1,600 e-tailers. These businesses earned

between $81 million to $106 million in 2009.

Summary of Retailers

We estimate that retailers as a whole earn between $278 million and $364 million from

sales of reptiles and related products annually. Table 2.10 summarizes our revenue estimates for

reptile retailers.

Table 2.10

Summary of 2009 Annual Revenues For U.S. Reptile Retailers

Retailer

Category

Estimated

Number

of Businesses

Estimated

Annual Revenue

(in million $)

Low

High

Low

High

Superstores

2

2

19.0

22.5

Pet Stores

1,100

1,500

163.0

215.7

Hobbyists

600

800

14.6

19.5

E-tailers

1,200

1,600

81.0

106.1

Total

2,902

3,902

277.6

363.8

Source: GES estimates based on Major Business Survey and Small

Businesses Survey

-32-

Ancillary Reptile Products and Services

The increase in reptile ownership in the United States and around the world has given rise

to several industries dedicated to helping reptiles to lead longer, healthier lives. Manufacturers

make products to simulate the light, heat, and humidity of individual reptiles’ native

environments; bug and rodent breeders provide reptiles with a diet that these reptiles would find

in the wild; and veterinarians and pharmaceutical companies make sure that reptiles stay disease

and parasite free.

Manufacturers

There are roughly 40 to 60 manufacturers that make products for reptiles in the U.S.

66

These companies range in size and product assortment from three-person, single product

companies, to companies with hundreds of employees that produce a full range of reptile

products. These products include food pellets, lighting, terrariums, terrarium decorations,

heating products, vitamins and supplements, thermostats, snake hooks, sexing tools, and

humidity products. The majority of product manufacturers do not have captive sales and

distribution networks and must rely on independent distributors to supply their products to pet

stores.

67

We classify reptile product manufacturers by the variety of products that they offer, their

annual sales, and how widely their products are distributed. There are roughly three categories,

which we refer to as “tiers” of reptile product manufacturers:

66

Based on personal communications with reptile product manufacturers.

67

Based on responses to the Major Business Survey.

-33-

The companies that produce the greatest number and variety of products and

generate the highest annual sales, i.e. the top tier manufacturers, are Zoo Med

Laboratories, Rolf C. Hagen USA, Fluker Laboratories, Tetra, and Central Garden

& Pet.

68

Top tier brands are universally recognized by reptile enthusiasts. These

companies supply the superstore retailers as well as the most of the storefronts and

e-tailers. Collectively, the top tier companies earn the majority of product

manufacturing revenues. Unlike most other manufacturers, some of these

businesses such as Central Pet & Garden

69

and Rolf C. Hagen USA

70

have their

own distribution networks to distribute their products and the products of other

manufacturers across the United States.

The second tier is made up of companies with national distribution and a national

reputation, but a more limited product line and lower annual sales than the top tier

manufacturers. Most of these companies tend to focus on a small number of

product types. For example, Vision Products focuses on cages and bowls. Products

from second tier companies are sold at storefronts and, in many cases, at

superstores. They are often brands that are featured by online retailers. There are

roughly eight to ten second tier manufacturers. Some examples of second tier

companies are Nature Zone, Pet Tech, and T-Rex Products.

Third tier companies are more local in scope and narrow in product range than first

or second tier manufacturers. These companies tend to focus on one type of

product, like cages or supplements. Often these businesses will also be involved in

other sectors of the reptile industry, such as reptile, cricket, or rodent breeding.

Some of these companies also produce products for other animals. There are

approximately 30 to 50 third tier manufacturers. Some examples of third tier

manufacturers include HBH Pet Products, which makes flavored pellets for turtles;

Natural Chemistry, which makes sprays to kill reptile parasites and clean

enclosures; and Helix Controls, which makes thermometers, thermostats, and

heating products.

Table 2.11 summarizes our revenues estimates for reptile product retailers.

68

See “Market Leaders In Key Pet Supply Categories by Percentage of Stores Citing Brand as No.

1”, Petage.com, January 2010. Rankings for manufacturers were confirmed through discussions with

retailers and product manufacturers.

69

Central Pet & Garden’s 2009 10-K, p. 5.

70

Distribution information can be found on Hagen’s website. http://hagen.com/usa/about.cfm

(Accessed November 17, 2010)

-34-

TABLE 2.11

Estimated Annual Revenues For

U.S. Reptile Ancillary Product Manufacturers, 2009

Manufacturer

Category

Estimated

Number of

Businesses

Estimated Annual Revenues

(in million $)

(Low)

(High)

(Low)

(High)

Top Tier

71

5

5

50

60

Second Tier

8

10

5

8

Third Tier

30

50

1.5

2.5

Total

43

65

56.5

70.5

Source: GES estimates based on Major Business Survey and

Small Businesses Survey

Reptile Product Distributors

Beside a few companies in the top tier, most reptile product manufacturers rely on

wholesalers and distributors to transport and sell their products to superstores, pet stores, and

hobbyist stores across the country. We were not able to get in contact with reptile product

distributors and therefore were not able to estimate the total annual income generated by this

segment.

Live Reptile Food Breeders

Live reptile food breeders provide reptiles with foods that more closely resemble their

diet in the wild. The three main types of creatures bred for reptiles are rodents, insects, and

worms. Rodents are fed mostly to snakes and some larger lizards. Lizards and turtles are fed

insects and worms. The most popular rodents bred for snakes are mice and rats. The most

popular foods bred for lizards and turtles are crickets, mealworms, and superworms.

71

Several reptile industry insiders have suggested that Table 2.16 significantly underestimates

annual revenues for top tier manufacturers. Our income estimate for this manufacturer category has a

high margin of error because of the low response rate among top tier manufacturers to our survey.

-35-

Most mice and rats are shipped frozen. However, several businesses deliver live mice.

Transportation costs make delivery of live rodents prohibitively expensive outside of a 50 to 150

mile radius around a breeding or holding facility. All bugs

72

are shipped live. Almost all rodents

and bugs used to feed reptiles are sold to pet stores and distributors before they reach

consumers.

73

Among both the rodent and bug breeders, a small number of companies make the

majority of the sales. Leading food breeders focus on breeding food for reptiles and other

animals. Smaller food breeders tend to breed bugs and rodents to feed their own animals as well

as to sell to other breeders. Leading rodent breeders include Mice Direct and Rodent Pro.

Leading insect breeders include Timberline Live Pet Foods and Armstrong Crickets. Leading

worm breeders include Rainbow Mealworms and Nature’s Way.

Thirty years ago most bugs were bred as bait for fishing. Bug farms were established

near popular fishing spots to serve anglers. As reptiles gained in popularity as pets, bug breeders

shifted more of their breeding toward reptiles. These breeders appreciated the constant year

round demand that reptiles have for bugs, as opposed to the seasonal- and weather-dependant