ACHI is a nonpartisan, independent, health policy center that serves as a catalyst to improve the health of Arkansans.

1401 W Capitol Avenue, Suite 300 ● Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 ● (501) 526-2244 ● www.achi.net

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program

(‘Private Option’)

Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver

Final Report

June 30, 2018

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

About the Evaluators

The Arkansas Center for Health Improvement (ACHI) is a nonpartisan, independent health policy center whose

vision is to be a trusted health policy leader committed to innovations that improve the health of Arkansans. This

vision is carried out through ACHI’s mission to be a catalyst for improving the health of Arkansans through

evidence-based research, public issue advocacy, and collaborative program development. In undertaking this

mission, ACHI has worked hard to develop and adhere to an important set of values that guide the Center.

ACHI’s core values are commitment, initiative, trust, and innovation. These are the fundamental principles that

guide the Center’s collective and individual decisions, strategies, and actions to advance the health of Arkansans.

These core values define what ACHI — the organization and its people — stands for throughout time, regardless

of changes in ACHI’s internal structure and leadership, or in response to external factors and environmental

conditions.

ACHI Team

Joseph W. Thompson, MD, MPH, Director

Anthony Goudie, PhD, Director of Research and Evaluation

Nichole Sanders, PhD, Assistant Director of Analytics

Kanna Lewis, PhD, Health Policy Data Architect

Vanessa White, BA, Project Coordinator

Stephen Lein, MS, Senior Data Analyst

Judy Bennett, MS, Senior Research Analyst

Pader Moua, MPH, Policy Analyst

Tim Holder, BA, Technical Editor

John Lyon, BA, Strategic Communications Manager

Vaishali Thombre, MBA, MS, Senior Research Analyst

Jeral Self, MPH, Senior Data Analyst

Kenley Money, MA, MFA, Director of Information Systems Architecture

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Evaluators

Anthony Goudie, PhD

Director of Research and Evaluation, Arkansas Center for Health Improvement

Assistant Professor, Center for Applied Research and Evaluation, Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine,

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Assistant Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health,

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

John “Mick” Tilford, PhD

Professor and Department Chair, Department of Health Policy and Management, Fay W. Boozman College

of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical Evaluation and Policy, College of Pharmacy, University of

Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Bradley Martin, PharmD, PhD

Professor, Division Head, Department of Pharmaceutical Evaluation and Policy, College of Pharmacy,

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Comparative Effectiveness Research Program Co-Director, Translational Research Institute, University of

Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Teresa Hudson, PharmD, PhD

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Director, Division of Health Services Research, College of Medicine,

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Director, National Rural Evaluation Center, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Associate Director, Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Jeffrey Pyne, MD

Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Arkansas

for Medical Sciences

Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, University of Arkansas for

Medical Sciences

Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for

Medical Sciences

Staff Physician, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System

Associate Director for Research and Site Leader for Community Engagement, South Central (VISN 16)

Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center

Research Health Scientist and Core Investigator, Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research,

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Chenghui Li, PhD

Associate Professor, Division of Pharmaceutical Evaluation and Policy, College of Pharmacy, University of

Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Nalin Payakachat, PhD

Associate Professor, Division of Pharmaceutical Evaluation and Policy, College of Pharmacy, University of

Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

UAMS Research Support Team

Gary Moore, MS, Research Analyst

Xiaotong Han, MS, Biostatistician

Niranjan Kathe, MS, Graduate Research Assistant

Divyan Chopra, MS, Graduate Research Assistant

Naleen Raj Bhandari, MS, Graduate Research Assistant

Mahip Acharya, B Pharm, Graduate Research Assistant

Acknowledged Contributors

Heather L. Rouse, MSEd, PhD

Brady Rice, BS

Grayson Shelton, BS

Donald Poe, BS

Anuj Shah, PhD

Siqing Li, MS

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Acknowledgements

Private Option Evaluation National Advisory Committee

The purpose of the National Advisory Committee (NAC) is to act as an external expert advisory group for the

Arkansas Section 1115 demonstration waiver evaluation. Members of the committee were asked to serve in the

capacity for the duration of the three-year evaluation period (2014-2017) and were selected based on their content

expertise and methodological experience. The committee is comprised of a diverse range of policy perspectives and

professional backgrounds.

Eduardo Sanchez, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Officer (CMO) for Prevention, American Heart Association National

Center

Darrell J. Gaskin, PhD, Deputy Director, Center for Health Disparities Solutions, Bloomberg School of Public

Health, Johns Hopkins University

Daniel Polsky, PhD, Executive Director, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania

Timothy S. Carey, MD, MPH, Sarah Graham Kenan Professor of Medicine, Departments of Medicine and Social

Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement

(ACHI).

Contributing ACHI authors include Joseph W. Thompson, MD, MPH, and Anthony Goudie, PhD.

Suggested Citation

Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’)

Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver Final Report. Little Rock, AR: Arkansas Center for Health Improvement, June

2018.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Abbreviations

ACHI Arkansas Center for Health Improvement

AHA The Arkansas Hospital Association

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

AID Arkansas Insurance Department

AV Actuarial Value

BNC Budget Neutrality Cap

CAHPS Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

CAST Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CPT Current Procedure Terminology

CSR Cost-Sharing Reduction

CY Calendar Year

DCO Department of County Operations

DHS Arkansas Department of Human Services

EHB Essential Health Benefit

EPSD Early and Periodic Screening and Diagnostic

ER Emergency Room

FFM Federally Facilitated Marketplace

FFS Fee-For-Service

FPL Federal Poverty Level

FQHC Federally Qualified Community Health Center

GME Graduate Medical Education

HbA1c Hemoglobin A1c

HCIP Health Care Independence Program

HEDIS Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

HIA Health Independence Accounts

LATE Local Average Treatment Effect

LDL-c Lipoprotein

LSM Least Squares Mean

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Marketplace Individual Health Insurance Marketplace

MDES Minimum Detectable (standardized) Effect Size

MEPS Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

MLR Medical Loss Ratio

NAC National Advisory Committee

NCQA National Committee for Quality Assurance

NEMT Non-Emergency Medical Transportation

NQF National Quality Forum

NYU New York University

PCCM Primary Care Case Management

PCP Primary Care Provider

PMPM Per Member Per Month

PMPY Per Member Per Year

PPACA Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

PY Person-Years

PY1 Program Year 1

PY2 Program Year 2

PY3 Program Year 3

QHP Qualified Health Plan

Questionnaire Healthcare Needs Assessment Questionnaire

RCT Randomized Controlled Trial

RD Regression Discontinuity

RE Relative Efficiency

RUCA Rural-Urban Commuting Area Code

SIPTW Stabilized Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

SNAP Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SSI Social Security Income

TEFRA Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act

UAMS University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

UPL Upper Payment Limit

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... i

Background ............................................................................................................................................................... i

Summary of Findings Based on Evaluation Hypotheses ........................................................................................... i

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................................... vi

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1

Background .............................................................................................................................................................. 1

Arkansas Profile ....................................................................................................................................................... 1

Arkansas Structure of Commercial Premium Assistance ......................................................................................... 2

Arkansas Structure of PPACA Eligibility and Enrollment ......................................................................................... 3

Arkansas HCIP Program Experience ......................................................................................................................... 6

Arkansas HCIP Evaluation Strategy .......................................................................................................................... 8

Research Design and Approach ................................................................................................................................... 9

Goals and Objectives................................................................................................................................................ 9

Programmatic Timeline and Reporting Requirements .......................................................................................... 10

Theoretical Approach............................................................................................................................................. 11

Hypotheses ............................................................................................................................................................ 13

Data Sources and Analytic Comparison Groups .................................................................................................... 14

Methodological Approaches .................................................................................................................................. 16

The First Year Experience ....................................................................................................................................... 18

Year 2 and Year 3 Waiver Impact Findings ................................................................................................................ 24

Introduction to Analyses ........................................................................................................................................ 24

Geographic and Realized Access Differences and Provider Reimbursement Comparison

between Medicaid and QHP Programs .................................................................................................................. 27

Differences in Comparison Groups by Comparison Populations ........................................................................... 31

Special Populations and Topic Studies ................................................................................................................... 43

Program Costs ............................................................................................................................................................ 71

Overview ................................................................................................................................................................ 71

Cost-Effectiveness .................................................................................................................................................. 72

Program Impact Simulation ................................................................................................................................... 73

Appendices .............................................................................................................................................................. A-1

Appendix A – Arkansas Evaluation Hypotheses: Proposed and Original Test Indicators .................................... A-1

Appendix B – Arkansas Evaluation Hypotheses .................................................................................................... B-1

Appendix C – Data Processing of Carrier Data ...................................................................................................... C-1

Appendix D – Study Subjects: Analytical Sample Extraction ............................................................................... D-1

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Appendix E – Statistical Modeling to Assess Effect Differences for Those Assigned to Medicaid and QHPs ....... E-1

Appendix F – Supplemental Payments, Claims Loading Process, and Per Member Per Month Logic ................. F-1

Appendix G – Geographic Information System (GIS) Processing ......................................................................... G-1

Appendix H – Weighted Average Price Calculations............................................................................................ H-1

Appendix I – Pregnancy Analytic Profile ................................................................................................................ I-1

Appendix J – Opioid Use Outcomes ...................................................................................................................... J-1

Appendix K – Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Sample Size

Calculation, Sampling Strategy, and Data Preparation ......................................................................................... K-1

Table of Figures

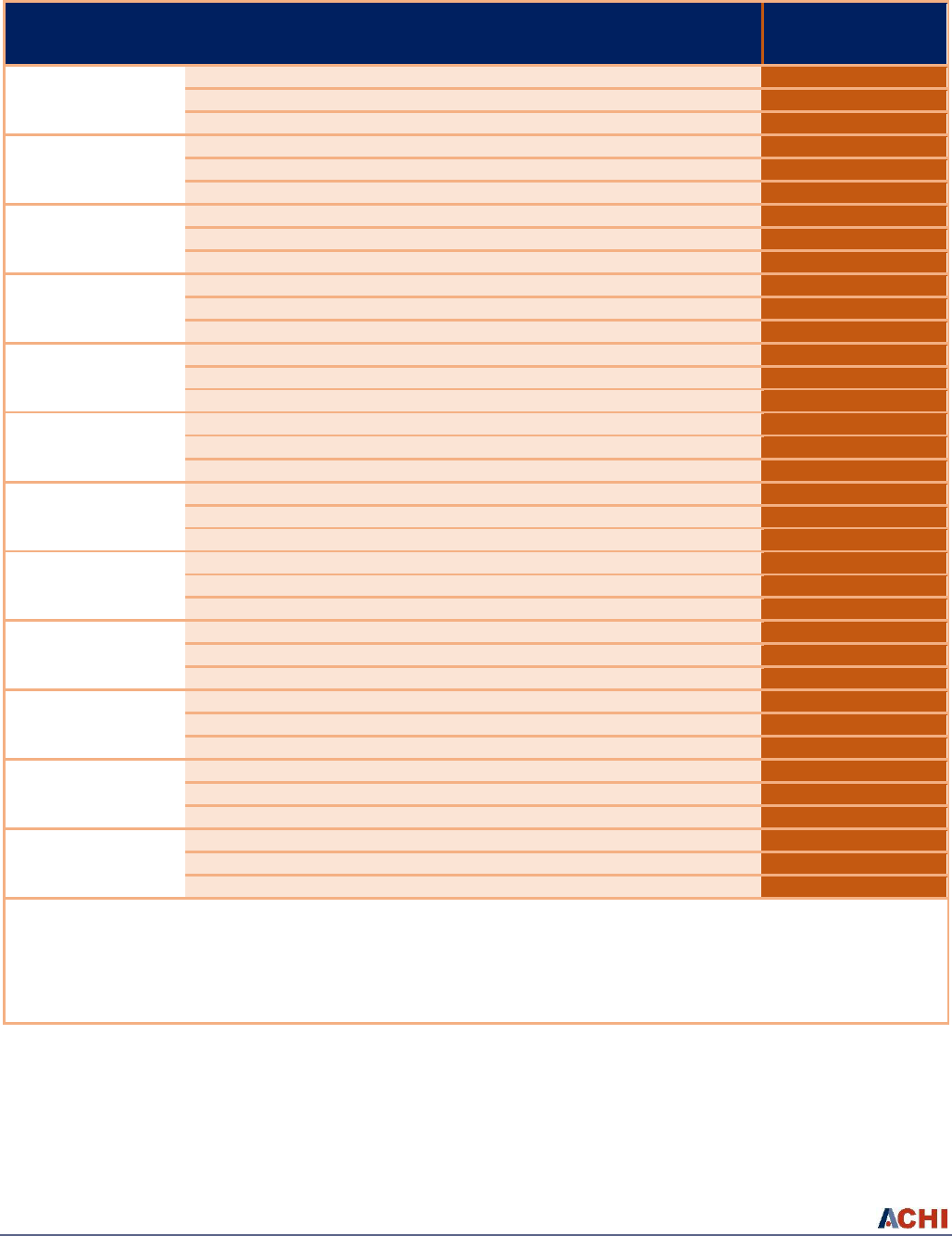

Figure 1. HCIP Premium and Cost-Sharing Reduction Breakdown ............................................................................... 3

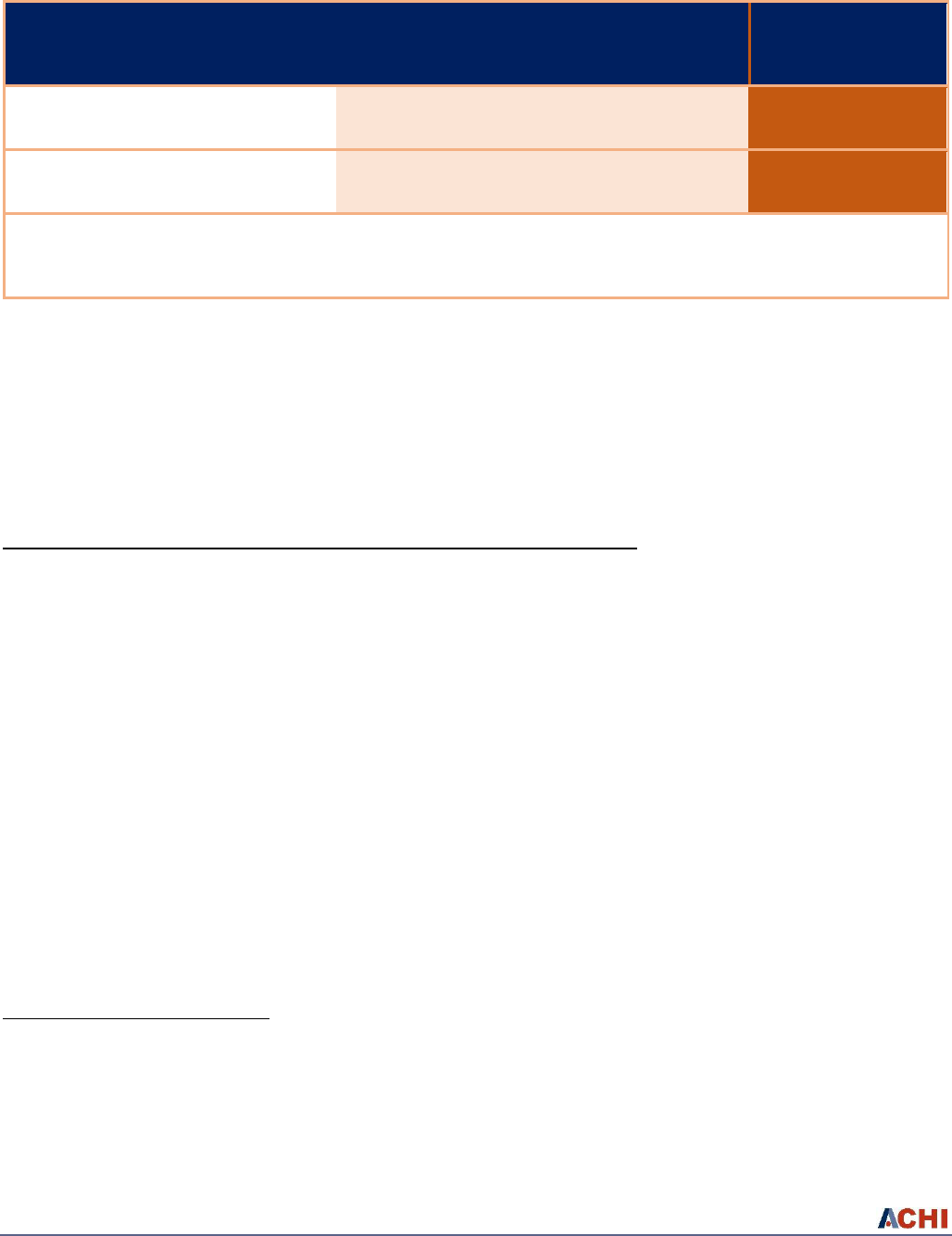

Figure 2. Enrollment Pathways and Plan Assignment Process ..................................................................................... 4

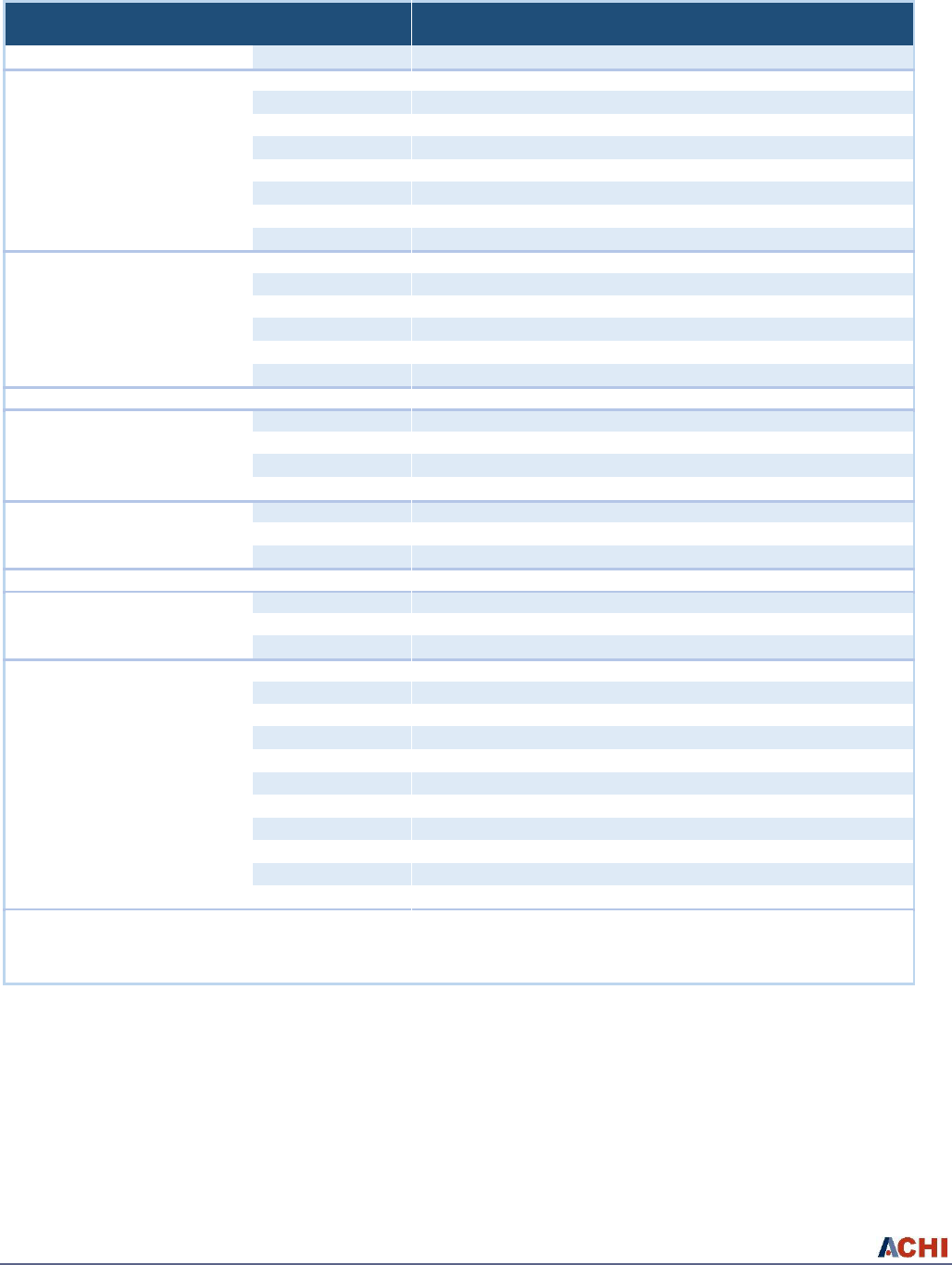

Figure 3. HCIP Monthly Enrollment, January 2014–December 2016 ........................................................................... 6

Figure 4. Enrollment Age Demographics by Category .................................................................................................. 7

Figure 5. Premium and Cost-Sharing Reduction Breakdown, January 2014–December 2016 .................................... 8

Figure 6. Arkansas Demonstration Waiver Evaluation Logic Model............................................................................. 9

Figure 7. Arkansas Health Care Independence Program Period: System Evaluation ................................................. 10

Figure 8. Proportion of Medicaid and QHP Enrollees with a First Outpatient Care Visit, by Day .............................. 31

Figure 9. Health Care Independence Program Enrollment by Program and Month .................................................. 52

Figure 10. Charlson Comorbidity Index by Health Independence Account Non-Participants

(Made No Payment) vs. Participants (Made Payment) .............................................................................................. 56

Figure 11. Access Improvement Simulation Model Studying Scenario-Based Price Increases

to Medicaid Providers to Reach Commercial PMPM Payments ................................................................................. 75

Table of Tables

Table 1. Comparison Group Description and Analytical Data Populations ................................................................ 15

Table 2. Differences in General Population Geographic Access to Health Care between Medicaid and QHP

Enrollees ..................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Table 3. Differences in Higher Needs Population Geographic Access to Health Care between Medicaid and

QHP Enrollees ............................................................................................................................................................. 29

Table 4. Medicaid and Commercial Payer Price Differences for Outpatient Procedures by Provider Type .............. 30

Table 5. Differences in Perceived Access to Health Care between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Propensity

Score Matched Comparison) ...................................................................................................................................... 32

Table 6. Differences in Primary Preventive Health Care between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Propensity

Score Matched Comparison) ...................................................................................................................................... 32

Table 7. Differences in Secondary and Tertiary Preventive Health Care between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees

(Propensity Score Matched Comparison) ................................................................................................................... 33

Table 8. Differences in the Percentage of Medicaid and QHP Enrollees Receiving Recommended Disease

Management (Propensity Score Matched Comparison) ............................................................................................ 34

Table 9. Differences in the Use of Healthcare Services between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Propensity

Score Matched Comparison) ...................................................................................................................................... 35

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Table 10. Differences in Rates of Preventable Hospitalizations and Readmissions between Medicaid and

QHP Enrollees (Propensity Score Matched Comparison) ........................................................................................... 36

Table 11. Differences in Utilization of Emergency Room Services between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees

(Propensity Score Matched Comparison) ................................................................................................................... 36

Table 12. Differences in Perceived Access to Health Care between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Regression

Discontinuity Comparison) ......................................................................................................................................... 37

Table 13. Differences in Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Preventive Health Care between Medicaid and

QHP Enrollees (Regression Discontinuity Comparison ............................................................................................... 38

Table 14. Differences in Secondary and Tertiary Preventive Health Care between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees

(Regression Discontinuity Comparison) ...................................................................................................................... 39

Table 15. Differences in the Percentage of Medicaid and QHP Enrollees Receiving Recommended Disease

Management (Regression Discontinuity Comparison) ............................................................................................... 40

Table 16. Differences in the Use of Healthcare Services between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Regression

Discontinuity Comparison) ......................................................................................................................................... 41

Table 17. Differences in Rates of Preventable Hospitalizations and Readmissions between Medicaid and

QHP Enrollees (Regression Discontinuity Comparison) .............................................................................................. 42

Table 18. Differences in Utilization of Emergency Room Services between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees

(Regression Discontinuity Comparison) ...................................................................................................................... 43

Table 19. Maternal Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes, with Description ...................................................................... 44

Table 20. Maternal Pregnancy Differences between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees .................................................. 46

Table 21. Pregnancy Birth Outcomes between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees ........................................................... 46

Table 22. Differences in Non-Emergency Transportation between General Population Medicaid and QHP

Enrollees ..................................................................................................................................................................... 48

Table 23. Differences in Non-Emergency Transportation between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Propensity

Score Matched Comparison) ...................................................................................................................................... 48

Table 24. Differences in Non-Emergency Transportation between Higher Needs Population Medicaid and

QHP Enrollees ............................................................................................................................................................. 48

Table 25. Differences in Non-Emergency Transportation between Medicaid and QHP Enrollees (Regression

Discontinuity Comparison) ......................................................................................................................................... 49

Table 26. Health Insurance Carrier at 19 Years of Age for Medicaid Screened and Diagnosed Sickle Cell

Disease, Cystic Fibrosis, or Hemophilia (n=151) ......................................................................................................... 50

Table 27. Medicaid Enrollment History of QHP and 06 Medicaid Individuals Enrolled in June 2015 ........................ 53

Table 28. The Impact of Redetermination on QHP and 06 Medicaid Enrollees (Enrolled in July 2015) .................... 53

Table 29. HCIP Enrollment History of Individuals Enrolled in HCIP During 2016........................................................ 54

Table 30. Health Independence Account Eligible Population Demographic Profile................................................... 56

Table 31. Health Independence Accounts Cost-Sharing Expenditures....................................................................... 56

Table 32. Characteristics of Unmatched and Propensity Score Matched General Population .................................. 59

Table 33. Opioid Use Measures for Propensity Score Matched General Population Medicaid and QHP by

Assessment Period ...................................................................................................................................................... 60

Table 34. Comparison of Opioid Utilization for General Population Medicaid and QHP Enrollees ........................... 60

Table 35. Comparison of Number of Opioid Prescriptions by General Population Medicaid and QHP

(Reference) Enrollees .................................................................................................................................................. 61

Table 36. Characteristics of Higher Needs Population ............................................................................................... 62

Table 37. Opioid Use Measures for Propensity Score Matched Higher Needs Population Medicaid and QHP by

Assessment Period ...................................................................................................................................................... 62

Table 38. Comparison of Opioid Utilization for Medicaid and QHP Higher Needs Population Enrollees .................. 63

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report

Table 39. Change in Estimated Rate of Non-Emergent Emergency Room Visits per 100 Person-Years .................... 64

Table 40. Unadjusted Analysis of Urgent Care Facility Utilization and Cost ............................................................... 65

Table 41. Medicaid and QHP Enrollee General Population Propensity Score Matched Characteristics .................... 67

Table 42. Medicaid and QHP Enrollees General Population Propensity Score Matched Characteristics .................. 69

Table 43. Observed Utilization Rates (Per Member Per 100 Person-Years) for Medicaid and QHP Enrollees in

2014, 2015, and 2016 ................................................................................................................................................. 71

Table 44. Observed and Estimated PMPM Cost Scenarios for Medicaid and QHP Enrollees by Service

Category and Year ....................................................................................................................................................... 73

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report i

Executive Summary

Background

In 2013, like many other states across the country, Arkansas faced a complex series of political challenges

following the U.S Supreme Court decision on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care (PPACA) Act. Unlike any

other state in the South, however, Arkansas was able to successfully navigate these challenges to pursue a novel

approach to Medicaid expansion through the commercial sector. Through a Section 1115 demonstration waiver,

the state utilized premium assistance to secure private health insurance, offered on the newly formed individual

health insurance marketplace (the Marketplace), for individuals between 19 and 64 years of age with incomes at

or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).

i

In 2014, Arkansas successfully established the Health Care Independence Program (HCIP),

ii

commonly referred to

as the “Private Option,” as designed under the terms and conditions of the Section 1115 demonstration waiver.

Through 2015, the estimated target-enrollment population of approximately 250,000 was met. Approximately

25,000 additional individuals eligible under the PPACA — and deemed to have exceptional healthcare needs —

were enrolled in the traditional Medicaid program. Finally, approximately 20,000 previously eligible but newly

enrolled individuals also obtained Medicaid coverage. By the end of 2016, the Private Option population totaled

approximately 280,000.

Arkansas’s healthcare providers have reported significant clinical and financial effects under the HCIP. In 2014,

federally qualified community health centers (FQHCs) reported increased success in attaining needed specialty

referrals for their clients.

iii

The Arkansas Hospital Association (AHA) reported significant annualized reductions in

uninsured outpatient visits (45.7 percent reduction), emergency room (ER) visits (38.8 percent reduction), and

hospital admissions (48.7 percent reduction).

iv

The state’s public teaching hospital reported a reduction in uninsured

admissions, from 16 percent to 3 percent, during the same time period.

v

These reductions persisted through 2016.

Competitiveness and consumer choice in the Marketplace have increased across the seven market regions in the

state with approximately 80 percent of the covered lives in the Marketplace enrolled through the Private Option.

In 2014, individuals in three out of the seven regions of the state — those marked by extreme poverty — only had

access to Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield and Blue Cross Blue Shield Multi-State plans. By 2016, five carriers

were offering coverage across all seven market regions, with one market region having access to six carriers. A

sixth carrier operated in a single region restricted by Medicaid’s purchasing guidance limiting premium assistance

to those plans within 10 percent of the second-lowest cost silver plan in the market region. Over the three year

period, all plans experienced single digit rate increases.

For 2014, the estimated budget neutrality cap (BNC) was exceeded during the initial enrollment phase of the

program. The enrollment of younger individuals over time (affecting net premiums), the rebate of medical-loss

ratio (MLR) payments by one carrier not meeting the minimum MLR requirements in 2014, and inflationary

expectations brought cumulative program costs within the estimated BNC 2015 limit of $500.08 per member per

month (PMPM) and well under the 2016 limit of $523.58 PMPM.

Summary of Findings Based on Evaluation Hypotheses

The HCIP programmatic goals and objectives included successful enrollment, enhanced access to quality health

care, improved quality of care and outcomes, and enhanced continuity of coverage and care at times of re-

enrollment and during income fluctuations. These goals and objectives were to be achieved within a cost-effective

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report ii

framework for the Medicaid program, compared with what would have occurred if the state had provided

coverage to the same expansion group in Arkansas’s traditional Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) delivery system.

The state’s required evaluation design under the terms and conditions of the Private Option waiver was

negotiated within 135 days of approval of the waiver on Sept. 27, 2013. The terms and conditions required the

evaluation to meet prevailing standards of scientific rigor, use the best available data, use controls and

adjustments for reporting limitations of the data, and discuss generalizability of results. Additional requirements

included a robust discussion of cost effectiveness. The state was required to submit a final Interim Evaluation

Report within 180 days of the end of the second year of the demonstration. That report is available

at www.achi.net.

The evaluation was conducted independently and with oversight of a National Advisory Committee consisting of

established leaders in major academic and medical centers around the country. The evaluation employed the

most current and well-established research design techniques to optimize confidence in observed findings. There

were two principle comparisons — the experiences of those with “Higher Needs” and that of the “General

Population.”

The Higher Needs population examined the approximately one-half of the newly eligible expansion population

who took a medical frailty screener to detect prior conditions and utilization. This information was used to

identify and compare similar individuals with higher needs that were placed in the traditional Medicaid program

versus those placed in QHPs through a quasi-experimental regression discontinuity approach.

The General Population consisted of the one-half of newly eligible that did not take the screener and were placed

in QHPs. They were paired with the approximately 40,000 newly enrolled adult Medicaid beneficiaries (woodwork

effect) and were matched using advanced propensity score techniques with appropriate statistical tests applied.

This report reflects the experience and findings from the three-year waiver for the Private Option, and major

findings are summarized below, grouped by questions of interest.

1. What were differences across access, quality, and outcomes between those enrolled in Medicaid and

those enrolled in commercial Qualified Health Plans (QHPs)?

A major assumption grounded in Arkansas’s use of premium assistance through the Marketplace was that

by utilizing the delivery system available to the privately enrolled individuals in the Marketplace, the

availability and accessibility of both primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists would be greater than

what would have been expected if Arkansas had utilized a traditional Medicaid expansion strategy. A

three-year enrollment comparison of Medicaid and commercial QHP beneficiaries in both the cohort with

Higher Needs and that in the General Population revealed:

The geographic proximity of available primary and specialty providers were similar for those

served by Medicaid and the QHP networks, and both met network adequacy requirements of the

Arkansas Insurance Department.

Initiation of care occurred more rapidly for enrollees in QHPs than for those in the Medicaid

program following enrollment.

In 2014, differences in the accessibility of both primary care and specialty providers were

reported, with QHP enrollees experiencing increased ability to get needed “care, tests, and

treatment” and receiving “an appointment for a check-up or routine care as soon as needed,”

compared to their Medicaid counterparts.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report iii

Perceived access differences improved after 18 months in the program for the General

Population. However, for individuals in the Higher Needs Population, Medicaid enrollees

continued to report more difficulty “receiving care when they needed it right away” and did not

always “find it easy to get the care, tests, and treatments they need,” compared to QHP enrollees

(range of differences 31-36 percent).

For Emergency Room (ER) use, differences were only observed within the General Population, in

which Medicaid enrollees experienced more ER visits in total, for both emergent and non-

emergent reasons, compared to QHP enrollees over the three years enrolled.

With the exception of QHP enrollees experiencing longer hospital stays compared to Medicaid

enrollees, there are no consistent differences across hospitalization measures.

For clinical services assessed for both populations — and for most measures studied — differences

in care and clinical service delivery were observed.

QHP enrollees were significantly more likely to receive individual clinical preventive services and

were more likely to receive all recommended screenings (a range of 24-94 percent relative

differences for the General Population).

QHP enrollees were significantly more likely to receive appropriate disease management services

and more likely to adhere to appropriate medication management than Medicaid enrollees (a

range of 31-55 percent relative differences for the General Population).

For pregnancy related care, no clinically significant differences were observed in the initiation of

prenatal services, complications of maternity care, or birth outcomes between QHP and Medicaid

enrollees.

With respect to non-emergency medical transportation, no differences were observed for the

General Population. However, for the Higher Needs Population, those in QHPs were 15 percent

less likely to miss a visit due to transportation issues.

Opioid use, while similar in the first year, diverged significantly in subsequent years, with

increasing numbers of prescriptions, high dose utilization, and concomitant benzodiazepine use in

the QHPs, compared to Medicaid enrollees.

With respect to Early Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) services, we found no

indication that needed services were not available to individuals in premium assistance.

With respect to continuity of enrollment, both Medicaid and QHP enrollees experienced few

disruptions in coverage, with the exception being a mass eligibility redetermination undertaken in

the summer of 2015.

There were no statistically significant differences in mortality within the first three years of the

program.

2. What were the differences in costs between Medicaid and premium assistance?

The cost of providing coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries through premium assistance in QHPs was

expected to be greater than providing coverage through the traditional Medicaid FFS system. Exploration

and characterization of the contrasts between the two programs provided a better understanding of the

observed variations in access, utilization, and clinical impacts described above. In addition, dramatic

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report iv

differences in payment rates were observed, with QHP rates consistently exceeding those in the Medicaid

program:

Physician payment rates across outpatient services were approximately 95 percent higher in each

of the three years under study for enrollees in a QHP compared to their Medicaid counterparts

(e.g., In 2016, the weighted average per PCP visit was $94.03 for a QHP compared to $47.69 for

Medicaid);

For inpatient hospital stays, average QHP payments averaged $12,270 per discharge compared to

Medicaid payments of $7,778 (a 53 percent difference); and

In 2016, administrative costs were estimated to be $91.65 PMPM for QHPs and $64.33 PMPM for

Medicaid (a 29.8 percent difference).

Utilization differences were also observed, but not at the same magnitude as payment differentials.

Medicaid beneficiaries, under the traditional FFS system, experienced increased ER visits and

hospitalizations. Conversely, QHP beneficiaries received more outpatient visit contacts, and by 2016,

almost twice as many prescriptions.

3. What were the cost-effective aspects of premium assistance?

Cost-effectiveness for the purposes of this evaluation considered any benefits associated with care

delivered through QHPs at increased payment rates. To assess cost-effectiveness, total program costs for

enrolled individuals in QHPs were directly compared to their Medicaid counterparts. Ratios of

improvement in care to associated costs were developed (e.g., access improvements, clinical, and

utilization differentials compared to payment rate differentials).

In 2016, the weighted average payment to QHPs (premium and cost-sharing reductions) was $486 PMPM

or $5,832 per year, compared to Medicaid costs of $317 PMPM or $3,804 per year for each enrollee

(using existing Medicaid payment rates). Using the difference of $167 PMPM, select ratios of

improvement to access reflect the following:

For colorectal cancer screening in the General Population, the QHP cohort had a 94 percent

higher relative difference in screening rates. Thus, the marginal improvement is suggested to be

an increase of 5.6 percent per observed 10 percent increase in program costs associated with use

of premium assistance.

For the proportion who received all indicated clinical preventive services in the General

Population, the QHP relative difference of 25 percent greater than Medicaid suggests a 1.4

percent improvement in clinical performance per observed 10 percent increase in program costs.

For individuals with Higher Needs, QHP enrollees were 26 percent more likely to self-report

“always getting care when needed right away” and 18 percent more likely to find it “easy to get

the care, tests, and treatment needed.” This suggests a 1.1 percent improvement in access, per

observed 10 percent increase in program costs.

For individuals with Higher Needs, Medicaid enrollees experienced fewer outpatient events and a

concurrent higher rate of ER visits and hospitalizations. For each observed 10 percent increase in

program costs, QHPs were projected to achieve seven more physician office visits and avoid 2.5

ER visits per 100 person years.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report v

There were no clinical indicators in which Medicaid was favored.

Importantly, enrollees in QHPs received twice as many prescriptions than their Medicaid

counterparts. For each 10 percent increase in program costs, QHPs were projected to cover 78

additional prescriptions per 100 person years.

Over the three-year evaluation, PMPM claims costs for QHPs increased, a trend which was associated

with both increased utilization rates and provider rate increases. The established Medicaid rate schedule

does not incorporate inflationary adjustments, so no comparable increases were observed during the

evaluation. Continued divergence in experience, utilization, and payment rates will likely affect ratios of

improvement in care to associated program costs.

4. What would the Medicaid program have experienced if a traditional Medicaid expansion had been

adopted?

A core component of this demonstration evaluation is an examination of the hypothetical costs of

covering the entire expansion population through Arkansas’s traditional Medicaid program and

identifying the programmatic changes that would be necessary to achieve a similar outcome to that

experienced through premium assistance. In 2013, prior to the PPACA expansion, Arkansas had one of the

lowest Medicaid eligibility thresholds for non-disabled adults in the U.S., covering only 24,955 non-

disabled adults with a full benefits package.

In 2014, following PPACA expansion, an additional 267,482 individuals were covered:

approximately 17,300 (6.5 percent) previously eligible but newly enrolled;

approximately 25,000 (9.3 percent) PPACA eligible but with exceptional healthcare needs;

and 225,000 (84.2 percent) PPACA eligible with premiums purchased on the individual marketplace.

These 267,482 individuals represented 16.0 percent of the total 19- to 64-year-old population in the state.

In 2016, this number increased to 330,943 covered lives:

approximately 22,375 (6.8 percent) PPACA eligible but with exceptional healthcare needs;

32,427 (9.8 percent) interim status before enrollment in a QHP;

and 276,141 (83.4 percent) PPACA eligible with premiums purchased on the individual marketplace.

vi

These 330,943 individuals represent 19.1 percent of the working-aged adults within the state.

Thus, because of the high rates of uninsurance and low Medicaid eligibility prior to the PPACA, Medicaid

has experienced a 13-fold increase in coverage for the non-disabled 19- to 64-year-old population.

Traditional microeconomics principles would suggest that increased demand through the expansion of the

Medicaid program would place increasing price pressure on the rate structure of the existing Medicaid

program. The observed differences in payment rates between QHPs and Medicaid described above could

lead to unsustainable access differentials for Medicaid enrollees. Any potential increase in payment rates

would affect not only the new expansion population, but also enrollees under the same payment rate

schedule across the entire Medicaid program. To model the potential effects, a budgetary impact analysis

was conducted on increasing payment rates across the Medicaid program.

Three increasingly fiscally conservative scenarios were simulated for alternative expansion options

through the existing Medicaid FFS system, the counterfactual, to provide policymakers with

conditions under which necessary increases to achieve equitable access could be considered. They

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report vi

included: 1) claims potentially associated with wage-sensitive services; 2) restricted claims associated

with major medical services; and 3) restricted to claims associated only with physician billed services.

The budget impact analysis revealed that costs to the Medicaid program would exceed the increased

costs associated with premium assistance:

if wage-sensitive payment rates had increased by 29 percent;

if claim payments associated with clinical services had increased by 45 percent; or

if physician-only claim payments had increased by 64 percent;

Importantly, under the most conservative scenario of increases restricted to physician-only claims, the

physician rate increase at which the Medicaid program costs exceed those of premium assistance remains

36 percent below the commercial payment rates observed. This suggests the likelihood of continued

differential access despite increased payments.

These findings suggest that with the 13-fold increase in enrollment of 19- to 64-year-olds, plausible

required increases in Medicaid payment rates across the entire program would exceed the costs

associated with purchasing commercial coverage through premium assistance.

Conclusion

The three-year evaluation of the Private Option is the first direct comparison of commercial insurance with

Medicaid since Medicaid’s inception in 1965. Through Arkansas’s use of premium assistance, and as a

consequence of the rigorous CMS evaluation requirements of the waiver, previously unfeasible direct

comparisons of system performance have been enabled.

Arkansas Medicaid achieves comparable participation in its network, compared to QHPs, for both primary and

specialty providers. However, likely due to markedly higher provider payment rates and more active enrollee

management, the network adequacy and clinical performance of the QHPs exceeds that of Medicaid. These

differences have an impact on the uptake of clinical preventive services, appropriate disease management, and

utilization of emergency room services. For those with Higher Needs, perceived barriers to getting care when

needed and getting necessary tests and treatments are persistent for Medicaid.

For pregnancy, where Medicaid previously covered a majority of deliveries and had invested significant

performance improvement efforts, no advantage was observed for treatment in the commercial sector at higher

reimbursement rates. In addition, Medicaid achieved reduced opioid consumption compared to the commercial

sector, likely due to more assertive programmatic restrictions.

In the first three years of the program, no differences in mortality were observed between enrollees in Medicaid

and those in the commercial sector.

Systemic effects on the Arkansas healthcare landscape through the use of premium assistance was significant. By

guaranteeing purchase for over 250,000 individuals and establishing purchasing guidelines, at a time when

surrounding states were facing major challenges in the stability of their markets, the Arkansas Health Insurance

Marketplace experienced exceptional stability, marked increase in competition, and single-digit rate increases

across the three years. In addition, Arkansas has experienced no hospital closures — with service expansion in

some underserved areas — further distinguishing its overall system stability from neighboring states and from the

rest of the country.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report vii

Finally, while the costs of premium assistance exceed those modeled under a static Medicaid expansion scenario,

it is unlikely that Arkansas Medicaid would have been able to absorb a 13-fold increase in enrollees and meet the

federal equal access requirements, under which the state is subject to judiciary review, without considerable

adjustment to provider rates. Although political discourse has highlighted concerns about the differences in

absolute cost between commercial and Medicaid alternatives, Medicaid expansion scenarios under which similar

clinical experiences would be achieved suggest budgetary outcomes that may mitigate these concerns.

These findings may have limited applicability to other states. Few states had the restrictive Medicaid eligibility

threshold, resulting in dramatic increases in coverage through expansion. In addition, provider rate differentials

between Medicaid and commercial plans are also unlikely to exceed those in Arkansas.

However, these findings do support direct comparisons of both commercial and Medicaid costs and performance

across states. These differential payment rates and associated results raise questions regarding the ability of

Medicaid programs nationwide to meet the federal equal access requirements through delivery system strategies

that pay providers significantly lower rates.

The innovative use of premium assistance and the integrated relationship between the individual Marketplace

and the Arkansas Medicaid program merit continued observation. The demonstration waiver through which

Arkansas implemented the Private Option was extended in January of 2017, enabling the successor premium

assistance program, “Arkansas Works.” With work requirements, workforce training, and/or community service

for a subset of enrollees implemented in June 2018, further evaluation of the use of premium assistance and the

impact on upward social mobility is warranted.

i

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Letter] to Andy Allison, Arkansas Department of Human Services. September

2013. https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-

Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-private-option-app-ltr-09272013.pdf.

ii

Ark. Code § 2-77-2405 (2014).

iii

Susan Ward-Jones, MD. Personal Communication. March 12, 2015.

iv

Arkansas Hospital Association. APO’s Hospital Impact Strong in 2014. The Notebook. 2015;22(22):1.

http://www.arkhospitals.org/archive/notebookpdf/Notebook_07-27-15.pdf.

v

Dan Rahn, M.D., Testimony before Health Reform Legislative Taskforce. August 20, 2015.

vi

Arkansas Department of Human Services (DHS). (2016, December 31). Arkansas Private Option 1115 Demonstration

Waiver. Quarterly Report October 1, 2016-December 31, 2016 [Report]. Retrieved from

https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-

Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-works-qtrly-rpt-oct-dec-2016.pdf

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 1

Introduction

Background

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2012 ruling

1

allowed states to decide whether to extend Medicaid benefits to their

citizens who qualified under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) expansion. This amplified the

political polarization about the PPACA at the state level, resulting in varied decisions about expansion. Historically,

states have had the option to implement Medicaid coverage through direct provider reimbursement, Medicaid

managed care contracts, or the purchase of coverage with premium assistance through employer-sponsored

coverage.

The state of Arkansas, navigating the political barriers facing many states, pursued a novel approach to expansion

through the commercial sector. Through a Section 1115 demonstration waiver, the state utilized premium

assistance to secure private individual health insurance offered on the newly formed individual health insurance

marketplace (the Marketplace) to individuals between 19 and 64 years of age with incomes at or below 138

percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).

2

The Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (HCIP),

3

commonly

referred to as the “Private Option,” provided coverage to more than 225,000 low-income Arkansans through

2015. By the end of 2016, approximately 300,000 individuals were enrolled.

One component of the waiver’s terms and conditions is a required evaluation of differences in access, quality,

outcomes, and efficiencies achieved through the use of commercial coverage for the low-income expansion

population.

4

The interim evaluation

5

examined first-year programmatic differences in both effects and costs

through commercial premium assistance compared to the experience that would have been achieved through a

traditional Medicaid expansion as a principal outcome of interest for the demonstration. The final evaluation, and

content of this report, examines the three-year experience of individuals enrolled in the HCIP program.

Arkansas Profile

Arkansas is a largely rural state with approximately 3 million citizens, many of whom face significant healthcare

challenges. These include high health-risk burdens, low median-family income, high rates of uninsured individuals,

and limited provider capacity, particularly in non-urban areas of the state. The Health Resources and Services

Administration has designated 74 of Arkansas’s 75 counties as medically underserved.

6

Prior to the PPACA, 25

percent of adult Arkansans between 18 and 64 years of age were without health insurance.

7

Arkansas’s Medicaid program prior to the HCIP had one of the most stringent eligibility thresholds in the nation

for adults, largely limiting coverage to the aged, disabled, and parents with extremely low incomes and limited

assets. Eligibility for adults between 19 and 64 years of age was restricted to parents/caretakers earning at, or

below, 17 percent FPL. Prior to expansion, non-disabled adults with full benefits comprised 18 percent of

Medicaid beneficiaries.

8

Expansion of the program under the PPACA more than doubled the number of eligible

19- to 64-year-old beneficiaries.

The Arkansas Medicaid program is a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) fee-for-service (FFS) based delivery

system. Individuals are assigned to a primary care provider (PCP) and providers may limit the number of Medicaid

beneficiaries assigned.

9

Medicaid provider reimbursement rates are significantly below their commercial

counterparts. Supplemental payments for select hospitals — critical access hospitals, public and private hospitals,

and state teaching hospitals — have been used to support delivery-system stability. Providers elect to join as a

qualified Medicaid provider, but may limit the number of Medicaid beneficiaries they serve.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 2

The commercial insurance marketplace has historically consisted of two carriers with statewide coverage,

including a dominant carrier with over 65 percent of private coverage penetration and other regional carriers. The

predominant network structure is preferred provider organizations with limited managed care and/or the

presence of restricted networks. This is, in part, due to Arkansas’s “any willing provider”

10

law, requiring insurers

to allow any provider willing to accept terms for the class of providers into their networks. Under the PPACA, the

state elected to utilize the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) partnership in which the state conducts plan

management and consumer outreach.

11

Proactive consumer outreach and advertising was limited to responsive

consumer support based upon state legislative restrictions.

Arkansas Structure of Commercial Premium Assistance

The Arkansas approach utilizing commercial premium assistance has several unique attributes that successfully

meet both Medicaid requirements and protections while enabling commercial sector independence. The state’s

approach was in large part based upon the hypotheses that Arkansas could not meet the equal access provision

requiring state Medicaid provider payments to be “consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care and

...sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available under the plan at least to the extent

that such care and services are available to the general population in the geographic area.”

12

Successful use of the

commercial plans offered on the Marketplace explicitly meet the equal access provision of Medicaid

requirements. However, several structural elements warrant acknowledgement and are described.

First, Medicaid’s purchase of individual commercial coverage via premium assistance is fundamentally different

from the historic use of Medicaid managed care. In premium assistance, the Medicaid program does not directly

contract with the private carrier but rather purchases plans offered on the individual marketplace. While a

memorandum of understanding was established between the state, Medicaid, the Arkansas Insurance

Department (AID), and each carrier to facilitate payments, plans are governed by AID through existing state law

and certification requirements (e.g., network adequacy). The Medicaid population is then integrated into the

privately insured risk pool, and provider payment rates are established by commercial carriers, not through

independent Medicaid contracts. Medicaid beneficiaries engage providers with commercial insurance cards and

are not separated into a Medicaid-specific program or plan.

Second, plans offered under the PPACA were utilized to meet a majority of the Medicaid cost-sharing protections.

For individuals at or below 100 percent FPL, the state utilized the 100 percent actuarial value (AV) plan required to

be available for Native Americans. For Medicaid beneficiaries between 101 and 138 percent FPL, the state utilized

the high-value silver 94 percent AV plan required to be offered on the Marketplace to individuals between 101

and 150 percent FPL. The remaining Medicaid-required cost-sharing protections were achieved through active

structuring of allowable deductibles and other cost sharing.

13

Importantly, these plans consist both of premiums

subject to medical-loss ratio (MLR) requirements of 80 percent and of cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) that are to

be fully reconciled (see Figure 1).

AID divided the state into seven geographic market regions, and carriers established age-specific premiums within

market regions (one carrier incorporated allowable tobacco use surcharges). The costs of premium assistance

through the individual marketplace was thus influenced by the premium variation based on age within each

market region, the age distribution of those deemed eligible, CSRs paid, and any subsequent repayments for

failure to meet MLR requirements or reconciliation of CSR.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 3

Figure 1. HCIP Premium and Cost-Sharing Reduction Breakdown

Finally, the impact of Medicaid’s guaranteed purchase in the individual insurance market had the potential to

convey stability to the individual marketplace and improve the actuarial profile of the risk pool. The HCIP Act

further extended potential benefits to the actuarial profile of the individual marketplace by requiring that

individuals who were medically frail or had exceptional healthcare needs requiring supplemental Medicaid

benefits would be retained in the traditional Medicaid program.

Arkansas Structure of PPACA Eligibility and Enrollment

As an FFM partnership with the state conducting plan management and consumer assistance combined with

Medicaid’s use of premium assistance, the Arkansas structure for PPACA eligibility and enrollment was complex.

Arkansas used three enrollment pathways for eligibility determination for beneficiaries: the Arkansas Department of

Human Services (DHS) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); an Arkansas eligibility web portal

(access.arkansas.gov); and the federal Healthcare.gov portal. Following eligibility determination, individuals were

directed to a separate enrollment portal (insureark.org) to facilitate a healthcare needs assessment and plan selection.

Additional cost-sharing reduction for

HCIP enrollees from 0% to 100% FPL

Deductible buy-down for HCIP enrollees

from 101% to 138% FPL

Cost-sharing reduction for enrollees

from 139% to 150% FPL

Premium

3.5%

2.5%

24.0%

70.0%

100%

PMPM cap including

wrap-around costs:

2014: $477.63

2015: $500.08

2016: $523.58

Audit Processes:

Subject to reconciliation

Subject to medical loss ratio

* Actual PMPM costs were $485.84 (186,950 enrollees) in 2014, $486.86 (200,703 enrollees) in 2015, and $478.61

(276,141 enrollees) in December 2016.

Source: “Arkansas Health Care Independence Program Annual Cap.” Arkansas Department of Human Services

and Arkansas Department of Human Services Final Private Option Report, 2016.

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 4

The SNAP-facilitated eligibility determination strategy was a time-limited effort to reach out to and engage with

potentially eligible beneficiaries. Through prior income determination for SNAP benefits, DHS identified

individuals and notified them of their eligibility. Redetermination of income or family composition was not

conducted. Individuals who affirmed their desire for coverage in response to the notice were directed to the

enrollment website. The Arkansas eligibility portal was utilized by DHS county offices, outreach workers,

community and faith-based organizations, and insurance agents across the state. Individuals thought to be

Medicaid-eligible were directed to the portal, where eligibility applications and FPL determinations were

processed. The enrollment pathways and plan assignment process for 2014 enrollment is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Enrollment Pathways and Plan Assignment Process

As in other states, individuals and the state both experienced challenges in the first year of the federal

Healthcare.gov portal.

14

Individuals identified through the federal portal and deemed to be Medicaid eligible were

transferred to the state for determination. Frequently, unsuccessful transfer of information resulted in

incomplete enrollments, with similar experiences noted by commercial carriers for individuals above 138 percent

FPL. Over time, the volume of enrollees and accuracy of eligibility information improved.

Two categories of eligible individuals were observed. One category was comprised of individuals who had

previously been eligible for traditional Medicaid benefits but had not enrolled and then subsequently applied and

were determined to be eligible. These individuals were placed into the Medicaid program. The second category

included individuals newly eligible under the PPACA — parents/caretakers from 18 to 138 percent FPL and

childless adults from 0 to 138 percent FPL. These individuals were eligible for commercial premium assistance

under the demonstration waiver. Prior to commercial enrollment, however, individuals were asked to complete a

Enrollment Portals

SNAP

Eligible

PPACA

Newly

Eligible

≤ 138% FPL

Previously

Eligible

Newly Enrolled

Plan

Selected

> 138%

FPL

Auto

Assigned

Federally

Facilitated

Health Insurance

Marketplace

(healthcare.gov)

Arkansas

Eligibility &

Enrollment

System

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 5

Healthcare Needs Assessment Questionnaire (the Questionnaire) to retain those with exceptional healthcare

needs in the traditional Medicaid program.

As required in the HCIP Act, these retained individuals were to include those “…determined to be more effectively

covered through the standard Medicaid program, such as an individual who is medically frail

a

or other individuals

with exceptional medical needs for whom coverage through the Health Insurance Marketplace is determined to

be impractical, overly complex, or would undermine continuity or effectiveness of care.” No previously developed

and validated tool for this purpose was known to exist.

The Arkansas Center for Health Improvement (ACHI) and the Arkansas DHS Division of Medical Services

collaborated with experts at the University of Michigan and the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality

(AHRQ) to develop a screener to identify newly eligible Medicaid applicants who had exceptional healthcare

needs. A pooled subsample from the Household Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS),

2005-2010,

15

was used to develop the Questionnaire and scoring thresholds. Questionnaire responses grouped

individuals into one of three categories:

1) Exceptional healthcare needs (Frail): those who reported exceptional healthcare needs as represented by

deficits in their “activities of daily living,” having severe mental illness, and/or being dependent or homeless;

2) Exceptional healthcare needs (Threshold): those who reported high healthcare use in the prior six months

through hospitalization, emergency room, and/or outpatient visits who met the predetermined threshold; or

3) No exceptional healthcare needs: those completing the Questionnaire who did not meet any criteria

outlined in (1) or exceed the predetermined threshold.

Individuals completing the screener and deemed as not having exceptional healthcare needs proceeded to select

plans offered on the individual marketplace through the state’s enrollment portal. The predetermined threshold

target was selected to achieve 10 percent retention for PPACA-newly eligible within the Medicaid program as

operationalized from the HCIP contract.

Importantly, approximately 50 percent of those determined to be PPACA eligible did not proceed to the

enrollment portal and complete the Questionnaire. After a maximum of 45 days, these individuals entered an

auto-assignment process. Individuals were auto-assigned to carriers based upon previously determined ratios tied

to the number of carriers in each of the seven insurance market regions. Auto-assigned individuals had a time-

limited opportunity to take the Questionnaire and choose to change carriers. Individuals could either choose to

stay with their assigned plan or choose another plan during subsequent open-enrollment periods each year or for

qualifying family events.

Following selection or auto-assignment, DHS executed monthly premium payments to the carriers on behalf of

the individuals. Individuals in the commercial plans received a letter with their Medicaid Identification Number (to

receive services prior to commercial plan coverage start date) and, subsequently, a commercial insurance card

from their carrier. Medicaid-retained individuals received a Medicaid benefit card.

In the second half of 2015 and all of 2016, DHS opted not to use the threshold method to identify individuals who

had exceptional healthcare needs. However, DHS continued use of the question about deficits in activities of daily

living to identify individuals with exceptional healthcare needs. New individuals enrolling in these years who did

not take the Questionnaire were still assigned to a QHP.

a

Note that “Medically Frail” as defined in the HCIP Act and operationalized in the HCIP preceded the current definition of

“Medically Frail” as found in 42 CFR 440.315(f).

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 6

Arkansas HCIP Program Experience

Figure 3. HCIP Monthly Enrollment, January 2014–December 2016

Enrollment in the HCIP and for other newly eligible individuals, both within Medicaid and for those above 138

percent FPL in the individual marketplace, resulted in a reduction in the uninsured rate for adults from 22.5

percent to 9.6 percent in 2014, the largest reduction observed nationwide.

16

More than 250,000 Arkansans

enrolled, with approximately 45,000 occurring through the SNAP-facilitated eligibility. In 2014, approximately half

completed the Questionnaire. Of the total new enrollees, 10 percent were deemed to have exceptional

healthcare needs and were maintained in traditional Medicaid. In 2014, an additional 22,000 adults previously

eligible (but not enrolled) for traditional Medicaid became newly enrolled in the program. In the three years of

the program, Medicaid has purchased individual plans covering at least one month for 399,330 individuals and

276,081 were enrolled in December 2016 (see Figure 3) through the premium assistance mechanism.

17

Through 2016, HCIP enrollees represent approximately 80 percent of the covered lives on the individual

marketplace. They are younger than their counterparts above 138 percent FPL participating in the Marketplace

(see Figure 4 for Year 1 age demographic comparison).

18

,

19

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

HCIP Commercial Insurance Coverage

2014

2015

2016

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 7

Carrier participation, and thus

beneficiary choice, has increased in

each market region. In 2014, of the

seven market regions, only three

had more than two carrier options.

Statewide, in 2016, every region

had at least five participating

carriers, with one region having six.

Premiums for the benchmark silver

plan in the largest market region

dropped 2.3 percent in 2015 and

experienced an increase of 3.7

percent in 2016.

20

Because

insurance premiums external to the

Marketplace are tied to those on

the Marketplace, similar rate effects were seen in the non-Marketplace PPACA-compliant market.

Healthcare providers have reported both significant clinical and financial effects. Federally qualified community

health centers (FQHCs) have reported increased success in attaining needed specialty referrals for their clients.

21

The Arkansas Hospital Association (AHA) compared service use and uninsured volumes between 2013 and 2014.

They found a 5 percent increase in ER visits overall, and a reduction in outpatient visits (45.7 percent), ER visits

(38.8 percent), and hospital admissions for the uninsured population.

22

The University of Arkansas for Medical

Sciences (UAMS) has reported a reduction in uninsured admissions, from 16 percent to 3 percent, during a similar

time period.

23

The Section 1115 demonstration waiver required an estimated budget neutrality cap (BNC) represented as a per-

member per month (PMPM) cost for program expenditures.

4

These expenditures include premiums, CSRs, and

required Medicaid benefits (wrap-around costs associated with required benefits, such as non-emergency

transportation) not covered through premium assistance. Average program expenditures over the program years

have been within the estimated budget neutrality caps established within the conditions of the Section 1115

demonstration waiver with cumulative program expenditures at the beginning of Program Year 3 (PY3) (January

2016) equal to $489.01 PMPM, 7.1 percent below the PY3 — Calendar Year (CY) 2016 — federal cap of $526.58.

During Program Year 1 (PY1) — CY 2014 — cumulative program expenditures exceeded the BNC, but were under

the estimated cap by Program Year 2 (PY2) — CY 2015. The first months of 2016 saw the PMPM under the BNC

but eventually exceeded it by the end of the year. Early in 2017 there was a substantial differential between

PMPM and the 9 percent increase in BNC from 2016.

17

This includes the effects due to the enrollment of younger

individuals over time affecting net premiums, the rebate of MLR premiums by one carrier who did not meet the

MLR requirements, and inflationary expectations built into the BNC estimates. Importantly, this evaluation will

replace BNC estimates with realized experience.

41%

25%

23%

19%

22%

23%

15% 33%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

With Premium Assistance Without Premium Assistance

Percentage Enrolled Through the

Health Insurance Marketplace

Age 34 and Younger Age 35-44 Age 45-54 Age 55-64

Figure 4. Enrollment Age Demographics by Category

Copyright © 2018 by the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. All rights reserved.

Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (‘Private Option’) Final Report 8

Figure 5. Premium and Cost-Sharing Reduction Breakdown, January 2014–December 2016

$477.63