32760

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

1

Exec. Order No. 14036, 86 FR 36987 (Jul. 9,

2021).

2

Report to the White House Competition Council:

U.S. Department of Transportation’s Investigatory,

Enforcement and Other Activities Addressing Lack

of Timely Airline Ticket Refunds Associated with

the COVID–19 Pandemic (Refund Report)

(September 9, 2021) at https://

www.transportation.gov/individuals/aviation-

consumer-protection/dot-report-airline-ticket-

refunds.

3

Refund Report at pages 11–12.

4

See FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of

2016, Pub. L. 114–190, July 15, 2016; 49 U.S.C.

41704 note.

5

81 FR 75347 (October 31, 2016).

6

86 FR 38420 (July 21, 2021).

7

49 U.S.C. 42301 note prec.

8

Business Travel Coalition et. al.,

FlyersRights.org, and Travelers United.

9

Airlines for America, International Air

Transport Association, Arab Air Carriers’

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Office of the Secretary

14 CFR Parts 259, 260, 262, and 399

[Docket No. DOT–OST–2022–0089 and

DOT–OST–2016–0208]

RIN 2105–AF04

Refunds and Other Consumer

Protections

AGENCY

: Office of the Secretary (OST),

Department of Transportation.

ACTION

: Final rule.

SUMMARY

: The U.S. Department of

Transportation (Department or DOT) is

requiring automatic refunds to

consumers when a U.S. air carrier or a

foreign air carrier cancels or makes a

significant change to a scheduled flight

to, from, or within the United States and

the consumer is not offered or rejects

alternative transportation and travel

credits, vouchers, or other

compensation. These automatic refunds

must be provided promptly, i.e., within

7 business days for credit card payments

and within 20 calendar days for other

forms of payment. To ensure consumers

know when they are entitled to a

refund, the Department is requiring

carriers and ticket agents to inform

consumers of their right to a refund if

that is the case before making an offer

for alternative transportation, travel

credits, vouchers, or other

compensation in lieu of refunds. Also,

the Department is defining, for the first

time, the terms ‘‘significant change’’ and

‘‘cancellation’’ to provide clarity and

consistency to consumers with respect

to their right to a refund. The

Department is also requiring refunds to

consumers for fees for ancillary services

that passengers paid for but did not

receive and for checked baggage fees if

the bag is significantly delayed. For

consumers who are unable to or advised

not to travel as scheduled on flights to,

from, or within the United States

because of a serious communicable

disease, the Department is requiring that

carriers provide travel vouchers or

credits that are transferrable and valid

for at least 5 years from the date of

issuance. Carriers may require

consumers to provide documentary

evidence demonstrating that they are

unable to travel or have been advised

not to travel to support their request for

a travel voucher or credit, unless the

Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS) publishes guidance

declaring that requiring such

documentary evidence is not in the

public interest.

DATES

: This rule is effective June 25,

2024. Upon OMB approval of the

information collection established in

this final rule, the Department will

publish a separate notice announcing

the effective date of the collection.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT

:

Clereece Kroha or Blane Workie, Office

of Aviation Consumer Protection, U.S.

Department of Transportation, 1200

New Jersey Ave. SE, Washington, DC,

20590, 202–366–9342 (phone),

[email protected] (email).

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

:

Executive Summary

(1) Purpose of the Regulatory Action

The purpose of this final rule is to

ensure that consumers are treated fairly

when they do not receive service that

they paid for or are unable or advised

not to travel because of a serious

communicable disease. This rule

responds to Executive Order 14036 on

Promoting Competition in the American

Economy (E.O. 14036), which was

issued on July 9, 2021.

1

The Executive

Order launched a whole-of-government

approach to strengthen competition and

requires the Department to take various

actions to promote the interests of

American consumers, workers, and

businesses.

Section 5, paragraph(m)(i)(C) of E.O.

14036 directs the Department to submit

a report to the White House Competition

Council on the progress of its

investigatory and enforcement activities

to address the failure of airlines to

provide timely refunds for flights

cancelled as a result of the COVID–19

pandemic. The Department submitted

its report to the White House in

September 2021.

2

In that report, the

Department explained that the lack of

definition regarding cancelled or

significantly changed flights had

resulted in inconsistency among carriers

on when passengers are entitled to a

refund. The Department also noted that

approximately 20% of the refund

complaints received during the first 18

months of the COVID–19 pandemic

involved instances in which passengers

with non-refundable tickets chose not to

travel given the COVID–19 pandemic

and stated that it planned to address

protections for these consumers in a

rulemaking.

3

The Executive Order in Section 5,

paragraph(m)(i)(D) further directs the

Department to publish a notice of

proposed rulemaking requiring airlines

to refund baggage fees when a

passenger’s luggage is substantially

delayed and to refund other ancillary

fees when passengers pay for a service

that is not provided.

(2) Background

The FAA Extension, Safety, and

Security Act of 2016 (FAA Extension

Act or Act) requires the Department to

issue a rule mandating that airlines

provide refunds to passengers for any

fee charged to transport a checked bag

if the bag is delayed as specified in the

Act.

4

On October 31, 2016, the

Department published an advance

notice of proposed rulemaking

(ANPRM) seeking comment on various

issues related to the requirement for

airlines to refund checked baggage fees

when they fail to deliver the bags in a

timely manner as provided by the FAA

Extension Act.

5

On July 21, 2021, the

Department published a notice of

proposed rulemaking titled ‘‘Refunding

Fees for Delayed Checked Bags and

Ancillary Services That Are Not

Provided’’ (Ancillary Fee Refund

NPRM).

6

Among other things, the

Ancillary Fee Refund NPRM proposed

that U.S. and foreign air carriers refund

the baggage fee paid for a checked bag

when they fail to deliver the bag to the

passenger within 12 hours of the arrival

of a domestic flight and within 25 hours

of the arrival of an international flight.

This NPRM further proposed ways to

measure the length of the baggage

delivery delay for the purpose of

determining whether a refund is due. In

addition, the Ancillary Fee Refund

NPRM also proposed to implement a

provision in the FAA Reauthorization

Act of 2018 regarding refunding fees for

ancillary services that are paid for but

not provided.

7

The Department received a total of 29

comments on the Ancillary Fee Refund

NPRM—three comments from consumer

rights advocacy groups,

8

16 comments

from U.S. and foreign airlines and

airline trade associations,

9

three

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32761

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

Association, Association of Asian Pacific Airlines,

National Air Carrier Association, Regional Airline

Association, Allegiant Air, Air New Zealand,

Condor Flugdienst GmbH, COPA Airlines, Emirates,

Kuwait Airways, Qatar Airways, Spirit Airlines,

United Airlines, and Virgin Atlantic.

10

American Society of Travel Advisors and

Travel Technology Association (Travel Technology

Association submitted two comments).

11

Panasonic Avionics Corporation.

12

87 FR 51550 (August 22, 2022). Prior to

publication in the Federal Register, on August 3,

2022, the NPRM was publicly available at https://

www.transportation.gov/airconsumer/latest-news

and at https://www.regulations.gov, docket number

DOT–OST–2022–0089.

13

The ACPAC is a statutorily required Federal

advisory committee that evaluates current aviation

consumer protection programs. It also provides

recommendations to the Secretary for improving

and establishing additional consumer protection

programs that may be needed. Information about

ACPAC is available at https://www.regulations.gov/

docket/DOT-OST-2018-0190.

14

In the request for extension of comment period

by the airline representatives, they included various

questions arising from the NPRM for which they

sought clarifications from the Department. The

Department responded to these questions and

placed the responses in the docket for this

rulemaking at DOT–OST–2022–0089.

comments from ticket agent trade

associations,

10

five comments from

individual consumers, one comment

from the Colorado Attorney General,

and one comment from an ancillary

service provider.

11

Overall, the

commenters provided various

suggestions on how the Department

should interpret and implement the

statutory mandate. Airlines asserted

they would face challenges to comply

with certain aspects of the proposed

baggage delivery deadlines and other

requirements, while consumers and

ticket agents supported a more stringent

standard under which a refund of

baggage fees is due.

In a separate effort to enhance air

travel consumer protection, on August

22, 2022, the Department published in

the Federal Register a notice of

proposed rulemaking titled ‘‘Airline

Ticket Refunds and Consumer

Protections’’ (Ticket Refund NPRM) to

propose measures to enhance

protections for consumers when airlines

cancel or make significant changes to

the scheduled itineraries to, from, or

within the United States.

12

Currently,

the Department’s regulations in 14 CFR

part 259 require that airlines provide

prompt refunds ‘‘when ticket refunds

are due.’’ Further, the Department’s

regulations in 14 CFR part 399 require

that ticket agents ‘‘make proper refunds

promptly when service cannot be

performed as contracted.’’ The

Department’s Office of Aviation

Consumer Protection has interpreted

these requirements and its statutory

authority to prohibit unfair and

deceptive practices as mandating

airlines and ticket agents provide

prompt refunds to passengers of both

the airfare and fees for prepaid ancillary

service fees if a flight is cancelled or

significantly changed and the passenger

does not continue his or her travel. The

Ticket Refund NPRM proposed to codify

the interpretation that when carriers

cancel flights or make significant

changes to flight itineraries and the

contracted service is not provided,

ticket refunds are due if consumers do

not accept the alternative transportation

offered by carriers or ticket agents. It

also proposed to define ‘‘significant

change of flight itinerary’’ and

‘‘cancelled flight’’ to protect consumers

and ensure consistency among carries

and ticket agents regarding when

passengers are entitled to refunds.

The Ticket Refund NPRM also

proposed to require airlines and ticket

agents to issue non-expiring travel

credits or vouchers, and under certain

circumstances, refunds in lieu of the

travel credits or vouchers, to consumers

when they: (1) are restricted or

prohibited from traveling by a

governmental entity due to a serious

communicable disease (e.g., as a result

of a stay at home order, entry restriction,

or border closure); (2) are advised by a

medical professional or determine

consistent with public health guidance

issued by the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC),

comparable agencies in other countries,

or the World Health Organization

(WHO) not to travel during a public

health emergency to protect themselves

from a serious communicable disease; or

(3) are advised by a medical

professional or determine consistent

with public health guidance issued by

CDC, comparable agencies in other

countries, or WHO not to travel,

irrespective of any declaration of a

public health emergency, because they

have or may have contracted a serious

communicable disease and their

condition would pose a direct threat to

the health of others. Under the

Department’s current regulations, there

is no requirement for an airline or a

ticket agent to issue a refund or travel

credit to a passenger holding a non-

refundable ticket when the airline

operated the flight and the passenger

does not travel, regardless of the reason

that the passenger does not travel. The

Ticket Refund NPRM’s proposals were

intended to protect consumers’ financial

interests when the disruptions to their

travel plans were caused by public

health concerns beyond their control,

and also to promote safe and adequate

air transportation by incentivizing

individuals to postpone travel when

they are advised by a medical

professional or determine, consistent

with public health guidance, not to

travel to protect themselves from a

serious communicable disease or

because they have or may have a serious

communicable disease that would pose

a threat to others.

Between August 2022 and January

2023, the Aviation Consumer Protection

Advisory Committee (ACPAC)

13

devoted substantial time in three

separate meetings to discuss the Ticket

Refund NPRM. At an all-day public

meeting on August 22, 2022, the ACPAC

heard the perspectives of consumer

advocates, airline and ticket agent

representatives, and members of the

public. Then, on December 9, 2022, the

ACPAC identified and deliberated on

potential recommendations on the

Ticket Refund NPRM. The ACPAC

voted on these recommendations at a

meeting held on January 12, 2023.

The Department initially provided a

comment period of 90 days on the

Ticket Refund NPRM (i.e., until

November 21, 2022). In September 2022,

Airlines for America (A4A), the

International Air Transport Association

(IATA), the Travel Technology

Association (Travel Tech), the American

Society of Travel Advisors (ASTA), and

the Travel Management Coalition

requested an extension of the comment

period.

14

The Department extended the

comment period to December 16, 2022.

In extending the comment period for an

additional 25 days, the Department

acknowledged that the NPRM raised

important issues that required in-depth

analysis and consideration by the

stakeholders. The Department also

noted that the ACPAC was expected to

meet on December 9 to deliberate on

what, if any, recommendations it would

make to the Department regarding this

rulemaking and its belief that extending

the comment period of the NPRM for

one week after the ACPAC meeting

would provide the public an

opportunity to consider and provide

comment on any recommendations of

the ACPAC.

On December 16, 2022, A4A and

IATA filed a petition to request a public

hearing on the NPRM pursuant to the

Department’s regulation on

discretionary rulemaking relating to

unfair and deceptive practices at 14 CFR

399.75. The Department granted the

request and conducted a public hearing

on March 21, 2023, to afford A4A,

IATA, and other stakeholders an

opportunity to present certain factual

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32762

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

issues that they asserted are pertinent to

the Department’s decision on the

rulemaking. At the hearing, the

Department heard from various

stakeholders and subject matter experts

on three issues regarding the Ticket

Refund NPRM: (1) whether consumers

can make reasonable self-determinations

regarding contracting a serious

communicable disease; (2) whether the

documentation requirement (medical

attestation and/or public health

guidance) is sufficient to prevent fraud;

and (3) how to determine whether a

downgrade of amenities or travel

experiences qualifies as a ‘‘significant

change of flight itinerary.’’ The

Department reopened the comment

period for seven days after the hearing

to allow the public the opportunity to

provide comments on issues discussed

at the hearing.

The Department received over 5,300

comments on the Ticket Refund NPRM

from consumer rights advocacy groups,

airlines and airline trade associations,

ticket agents and ticket agent trade

associations, academic researchers,

State attorneys general, and individual

consumers. Of the 5,300 comments,

approximately 4,600 comments are from

individual consumers or consumer

organizations, while approximately 24

comments are from airline

representatives and 650 comments are

from those representing ticket agents.

Almost all consumer commenters

expressed strong support of the

Department’s proposals to enhance

aviation consumer protection. The

industry commenters raised various

concerns about the NPRM proposals,

supporting some while urging the

Department to reconsider or revise

others.

The Department has carefully

reviewed and considered the comments

on the Ancillary Fee Refund NPRM and

the Ticket Refund NPRM received in the

rulemaking dockets, as well as

comments received during the March

2023 hearing and the recommendations

of the ACPAC. The Department is now

issuing a combined final rule for the

Ticket Refunds NPRM and the Ancillary

Fee Refund NPRM to significantly

strengthen protections for consumers

seeking refunds of: (1) airline tickets

when an airline cancels or significantly

changes a flight, and the consumer

rejects or is not offered alternative

transportation; (2) checked bag fees

when bags are significantly delayed; and

(3) ancillary services fees when

consumers pay for services, such as Wi-

Fi, that are not provided. In addition,

this final rule provides protections for

consumers who are unable or advised

not to travel because of a serious

communicable disease by requiring that

carriers provide these consumers travel

vouchers or credits that are transferrable

and valid for at least 5 years from the

date of issuance.

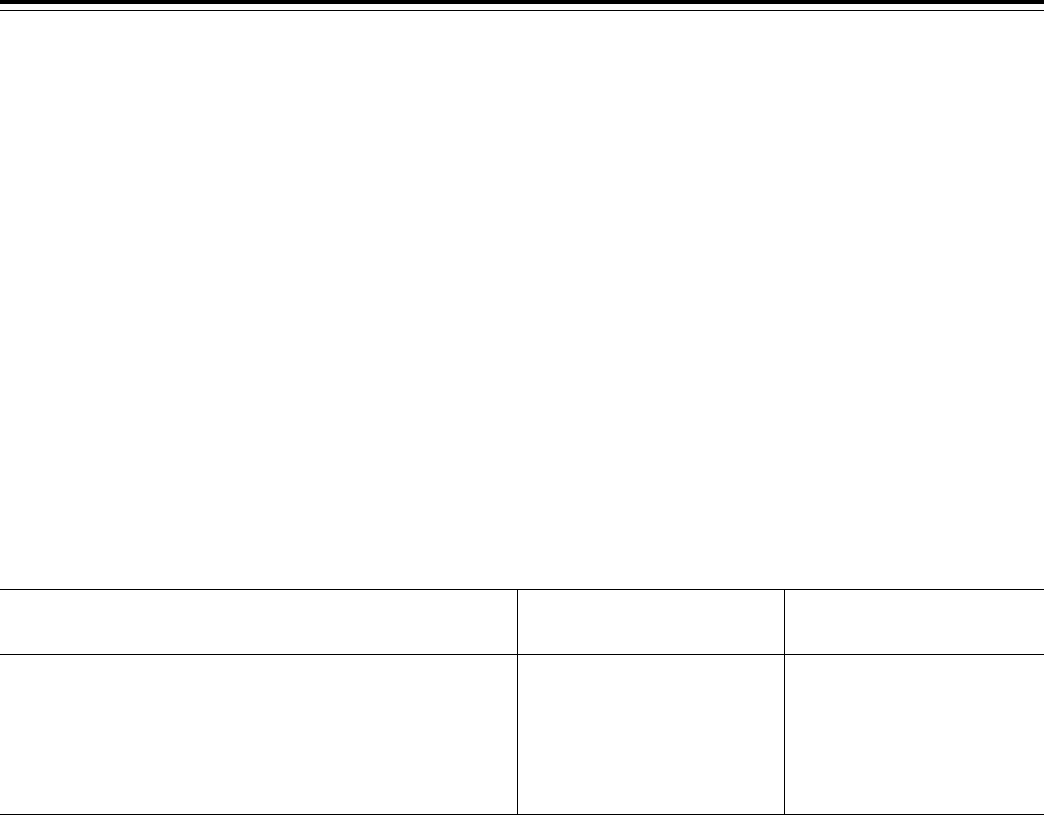

(3) Summary of Major Provisions

Subject Final rule

Definition of Cancelled Flight .............................. Amend 14 CFR part 399 and add 14 CFR part 260 to define cancelled flight as a flight that

was published in a carrier’s Computer Reservation System (CRS) at the time of the ticket

sale but not operated by the carrier.

Definition of Significant Change of Flight

Itinerary.

Amend 14 CFR part 399 and add 14 CFR part 260 to define significant change of flight

itinerary as a change to the itinerary made by a carrier where:

(1) the passenger is scheduled to depart from the origination airport three hours or more (for

domestic itineraries) or six hours or more (for international itineraries) earlier than the origi-

nal scheduled departure time;

(2) the passenger is scheduled to arrive at the destination airport three hours or more (for do-

mestic itineraries) or six hours or more (for international itineraries) later than the original

scheduled arrival time;

(3) the passenger is scheduled to depart from a different origination airport or arrive at a dif-

ferent destination airport;

(4) the passenger is scheduled to travel on an itinerary with more connection points than that

of the original itinerary;

(5) the passenger is downgraded to a lower class of service;

(6) the passenger with a disability is scheduled to travel through one or more connecting air-

ports that differ from the original itinerary; or

(7) the passenger with a disability is scheduled to travel on a substitute aircraft that results in

one or more accessibility features needed by the passenger being unavailable.

Entity Responsible for Refunding Airline Tickets Add 14 CFR part 260 to require U.S. and foreign air carriers that are the merchants of

record

15

of the ticket transactions to provide prompt refunds when they are due, including

for codeshare and interline itineraries.

Amend 14 CFR part 399 to require ticket agents that are merchants of record of the airline

ticket transactions to provide prompt ticket refunds when they are due.

16

Notification of Right to Refund ............................ Amend 14 CFR parts 259 and 399 to require U.S. and foreign airlines and ticket agents inform

consumers that they are entitled to a refund of the ticket if that is the case before making an

offer for alternative transportation or travel credits, vouchers, or other compensation in lieu

of refunds.

Add 14 CFR part 260 to require U.S. and foreign airlines to provide prompt notifications to

consumers affected by a cancelled or significantly changed flight of their right to a refund of

the ticket and ancillary fees due to airline-initiated cancellations or significant changes, any

offer of alternative transportation or travel credit, vouchers, or other compensation in lieu of

a refund, and airline policies on refunds and rebooking when consumers do not respond to

carriers’ offers of alternative transportation or travel credit, vouchers, or other compensation

in lieu of a refund.

‘‘Prompt’’ Ticket Refund ...................................... Amend 14 CFR parts 259 and 399 and add 14 CFR part 260 to specify ‘‘prompt’’ ticket refund

means:

(1) Airlines and ticket agents provide refunds for tickets purchased with credit cards within 7

business days of refunds becoming due; and

(2) Airlines and ticket agents refund tickets purchased with payments other than credit cards

within 20 calendar days of refunds becoming due.

Define ‘‘business days’’ to mean Monday through Friday excluding Federal holidays in the

United States.

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32763

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

Subject Final rule

Automatic Refunds of Airline Tickets .................. Add 14 CFR part 260 to require carriers who are the merchants of record to provide automatic

ticket refunds when:

(1) a carrier cancels a flight and does not offer alternative transportation or travel credits,

vouchers, or other compensation for the canceled flight in lieu of a refund;

(2) a carrier significantly changes a flight and the consumer rejects the significantly changed

flight itinerary and the carrier does not offer alternative transportation or offer travel credits,

vouchers, or other compensation in lieu of a refund;

(3) a consumer rejects the significantly changed flight or alternative transportation offered as

well as travel credits, vouchers, or other compensation offered for a canceled flight or a sig-

nificantly changed flight itinerary in lieu of a refund;

(4) a carrier offers a significantly changed flight or alternative transportation for a significantly

changed flight itinerary or a canceled flight, but the consumer does not respond to the trans-

portation offered on or before a response deadline set by the carrier and does not accept

any offer of travel credits, vouchers, or other compensation, and the carrier’s policy is to

treat a lack of a response as a rejection of the alternative transportation offered;

(5) a carrier does not offer a significantly changed flight or alternative transportation for a sig-

nificantly changed flight itinerary or a canceled flight but offers travel credits, vouchers, or

other compensation in lieu of a refund, and the consumer does not respond to the alter-

native compensation offered on or before a reasonable response date in which case the

lack of a response is deemed a rejection; or

(6) a carrier offers a significantly changed flight or alternative transportation for a significantly

changed flight itinerary or a canceled flight and offers travel credits, vouchers, or other com-

pensation in lieu of a refund and the carrier has not set a deadline to respond, the con-

sumer does not respond to the alternatives offered, and the consumer does not take the

flight.

Carriers may set a reasonable deadline for a consumer to accept or reject a significant

change to a flight or an offer of alternative transportation following a significant change or a

cancellation.

Carriers that set a deadline must establish, publish, and adhere to a policy regarding whether

consumers not responding to a significant change or an offer of alternative transportation

following a significant change or cancellation before the carrier’s deadline would: (1) have

their reservations cancelled and receive a refund; or (2) maintain their reservations and for-

feit the right to a refund.

Refunding Fees for Significantly Delayed Bags Add 14 CFR part 260 to require U.S. and foreign airlines that are merchants of record for the

checked bag fee or if a ticket agent is the merchant of record for the checked bag fee, the

carrier that operated the last flight segment to provide automatic refunds of checked bag-

gage fees when they fail to deliver checked bags in a timely manner:

(1) For domestic itineraries, a refund of baggage fee is due when an airline fails to deliver the

checked bag within 12 hours of the consumer’s flight arriving at the gate and the consumer

has filed a Mishandled Baggage Report.

(2) For international itineraries where the flight duration of the segment between the United

States and a point in a foreign country is 12 hours or less, a refund of baggage fee is due

when the airline fails to deliver the checked bag within 15 hours of the consumer’s flight ar-

riving at the gate and the consumer has filed a Mishandled Baggage Report.

(3) For international itineraries where the flight duration of the segment between the United

States and a point in a foreign country is over 12 hours, a refund of baggage fee is due

when the airline fails to deliver the checked bag within 30 hours of the consumer’s flight ar-

riving at the gate and the consumer has filed a Mishandled Baggage Report.

Refunding Ancillary Services Fees for Services

Not Provided.

Add 14 CFR part 260 to require U.S. and foreign airlines that are merchants of record for the

ancillary service or if a ticket agent is the merchant of record for the ancillary service, the

carrier that failed to provide the ancillary service to provide automatic refunds of ancillary

service fees when a passenger pays for an ancillary service that the airlines fail to provide.

Providing Travel Credits or Vouchers to Con-

sumers Affected by a Serious Communicable

Disease.

Add 14 CFR part 262 to require U.S. and foreign airlines that are merchants of record for the

ticket transaction or if a ticket agent is the merchant of record, the carrier that operated the

flight to issue travel credits or vouchers, valid for at least five years from the date of

issuance and transferrable, when:

(1) a consumer is advised by a licensed treating medical professional not to travel during a

public health emergency to protect himself/herself from a serious communicable disease,

the consumer purchased the airline ticket before a public health emergency was declared,

and the consumer is scheduled to travel during the public health emergency to or from the

area affected by the public health emergency;

(2) a consumer is prohibited from travel or is required to quarantine for a substantial portion of

the trip by a governmental entity in relation to a serious communicable disease and the con-

sumer purchased the airline ticket before a public health emergency for that area was de-

clared or, if there is no declaration of a public health emergency, before the government

prohibition or restriction for travel to or from that area is imposed; or

(3) a consumer is advised by a licensed treating medical professional not to travel, irrespec-

tive of a public health emergency, because the consumer has or is likely to have contracted

a serious communicable disease and would pose a direct threat to the health of others.

Documentation Requirement for Receiving

Credits or Vouchers.

Add 14 CFR part 262 to allow U.S. and foreign airlines to require consumers requesting a

credit or voucher for a non-refundable ticket when the flight is still scheduled to be operated

without significant change to provide, as appropriate:

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32764

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

15

Merchants of records are the entities shown in

the consumer’s financial charge statements such as

debit or credit card charge statements.

16

Comments from ticket agents assert that ticket

agents appear as merchants of records in less than

10 percent of transactions addressed in this final

rule.

17

14 CFR 399.79(b)(1).

18

14 CFR 399.79(c).

19

87 FR 52677 (August 28, 2022).

Subject Final rule

(1) the applicable government order or other document relating to a serious communicable

disease demonstrating how the passenger is prohibited from travel or is required to quar-

antine at the destination for a substantial portion of the trip; or

(2) a written statement from a licensed treating medical professional, attesting that it is the

medical professional’s opinion, based on current medical knowledge concerning a serious

communicable disease such as guidance issued by CDC or WHO and the passenger’s

health condition, that the passenger should not travel to protect the passenger from a seri-

ous communicable disease or the passenger would pose a direct threat to the health of oth-

ers if the passenger traveled. This medical statement may only be required in the absence

of HHS guidance declaring that requiring such documentation is not in the public interest.

Service Fees by Ticket Agents for Issuing Tick-

ets.

Amend 14 CFR part 399 to allow ticket agents to retain the service fee charged when issuing

the original ticket if the service provided is for more than processing payment for a flight that

the consumer found and so long as the fee is on a per-passenger basis and the existence,

amount, and the non-refundable nature of the fee if this is the case, is clearly and promi-

nently disclosed to consumers at the time they purchase the airfare.

Processing Fees for Issuing Refunds, Credits,

or Vouchers.

Retaining Processing Fee for Required Refunds: Add 14 CFR part 260 to prohibit carriers

from retaining a processing fee for issuing required refunds when the carrier cancels or sig-

nificantly changes a flight.

Processing Fee for Issuing Required Credits or Vouchers: Add 14 CFR part 262 to allow air-

lines to retain a processing fee from the value of a required travel credit or voucher pro-

vided to a passenger due to a serious communicable disease. Airlines (not ticket agents)

are responsible for issuing travel credits or vouchers to eligible consumers whose travel is

affected by a serious communicable disease.

(4) Costs and Benefits

The final rule will reduce

inconsistencies in granting consumers

airline ticket refunds that stem from the

lack of universal definitions for

cancellation and significant itinerary

change. As such, the rule is expected to

reduce the resources consumers need to

expend to obtain the refunds they are

owed. Consumer time savings are

estimated to be about $3.8 million

annually. The rule also implements

2016 and 2018 statutory mandates

pertaining to refunds of fees for delayed

baggage and ancillary services that a

consumer does not receive. The

expected economic impacts of the fee

refund provisions consist of $16.0

million annually in increased refunds to

consumers and $7.1 million annually in

administrative costs for the airlines.

The rule also requires airlines to

provide five-year transferable travel

credits or vouchers to passengers who

cancel travel for reasons related to a

serious communicable disease.

Expected societal benefits, which were

not quantified, are from infected air

passengers who cancel air travel due the

option of receiving the five-year travel

credit and the reduction in exposure of

uninfected passengers to serious

contagious disease. Estimated annual

costs range from $3.4 million to $482.0

million.

Statutory Authority

The Department is issuing this

rulemaking under its authority to

prohibit unfair or deceptive practices or

unfair methods of competition in air

transportation or the sale of air

transportation pursuant to 49 U.S.C.

41712, its authority to require safe and

adequate interstate transportation

pursuant to 49 U.S.C. 41702, its

authority to mandate that airlines

refund checked baggage fees to

passengers when they fail to deliver

checked bags in a timely manner

pursuant to 49 U.S.C. 41704 note, and

its authority to mandate that airlines

promptly provide a refund to a

passenger of any ancillary fees paid for

services related to air travel that the

passenger does not receive pursuant to

49 U.S.C. 42301 note prec.

Under the Department’s procedural

rule regarding rulemakings relating to

unfair and deceptive practices, 14 CFR

399.75, the Department is required to

provide its reasoning for concluding

that a certain practice is unfair or

deceptive to consumers, as defined in

14 CFR 399.79, when issuing aviation

consumer protection rulemakings that

are not specifically required by statute

and are based on the Department’s

general authority to prohibit unfair or

deceptive practices under 49 U.S.C.

41712. A practice is ‘‘unfair’’ to

consumers if it causes or is likely to

cause substantial injury, which is not

reasonably avoidable, and the harm is

not outweighed by benefits to

consumers or competition.

17

Proof of

intent is not necessary to establish

unfairness.

18

The elements of unfairness

are further elaborated by the Department

in its guidance document.

19

The Department has determined that

it is an unfair business practice in

violation of section 41712 for airlines or

ticket agents to refuse to refund

passengers when an airline cancels or

significantly changes a flight and

passengers do not accept the offered

alternative transportation or

compensation (e.g., airline credits or

vouchers) in lieu of a refund, regardless

of whether the passenger purchased a

non-refundable ticket. A practice by

airlines or ticket agents of not providing

refunds in such situations substantially

harms consumers because consumers

paid money for services that were not

provided when the airline cancelled or

significantly changed the flight. This

harm is not reasonably avoidable by

consumers as cancellations or

significant changes to their flights are

outside of their control. A reasonable

consumer would not expect that he or

she must pay more to purchase a

refundable ticket to be able to recoup

the ticket price when the airline fails to

provide the service through no action or

fault of the consumer. Also, the tangible

and significant harm to consumers of

not receiving a refund is not outweighed

by benefits to consumers or

competition. The Department

acknowledges that consumers may

benefit from the availability of lower

cost nonrefundable tickets but does not

expect that this requirement would

result in airlines no longer offering

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32765

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

nonrefundable tickets as the term

nonrefundable has generally been

understood not to apply in cases where

airlines cancel or make a significant

change in the service provided.

For airlines, this prohibited unfair

practice includes a carrier’s retention of

a fee to process a required refund or of

a booking fee (i.e., a fee for processing

payment for a flight that the consumer

found) because it is the carrier’s flight

that is significantly changed or

canceled; the Department is deferring

decision on whether the same

prohibition should apply to ticket

agents because ticket agents do not

operate the flight. Further, the

Department has determined that it is an

unfair and deceptive practice in

violation of section 41712 for airlines

and ticket agents to not inform

consumers that they are entitled to a

refund of the ticket and ancillary fees if

that is the case before making an offer

for travel credits, vouchers, or other

compensation in lieu of refunds. Also,

it is an unfair and deceptive practice to

not provide proper disclosures and

notifications to consumers with respect

to: the limitations, restrictions, and

conditions on any travel credits,

vouchers, or other compensation offered

in lieu of refunds; consumers’ rights to

automatic refunds under certain

circumstances; and any airline-imposed

requirements on accepting or rejecting

alternative transportation. Additionally,

to ensure that consumers who

purchased their airline tickets from a

ticket agent receive refunds that are due

in a timely manner, the Department has

determined that it is an unfair practice

for airlines to not confirm a consumer’s

refund eligibility in a timely manner.

The Department’s analysis on why these

actions by airlines or ticket agents

violate section 41712 will be provided

in each section that discusses these

matters in substance.

Similarly, the Department considers it

to be an unfair practice for an airline to

not provide travel credits or vouchers

when (1) a consumer is advised by a

licensed treating medical professional

not to travel to protect himself/herself

from a serious communicable disease

and the consumer purchased the airline

ticket before a public health emergency

affecting the origination or destination

of the consumer’s itinerary was declared

and is scheduled to travel to or from

that area during the public health

emergency; (2) a consumer is prohibited

from traveling or is required to

quarantine for a substantial portion of

the trip by a governmental entity due to

a serious communicable disease (e.g., as

a result of a stay-at-home order, border

closure) affecting the origination or

destination of the consumer’s itinerary

and the consumer purchased the airline

ticket before a public health emergency

was declared or, if there is no

declaration of a public health

emergency, before the government

prohibition or restriction for travel to

the consumer’s destination or from the

consumer’s origination; or (3) a

consumer is advised by a licensed

treating medical professional consistent

with public health guidance (e.g., CDC

guidance) not to travel to protect others

from a serious communicable disease.

Consumers are substantially harmed

when they pay for a service that they are

unable to use because they were

directed or advised by governmental

entities or a medical professional not to

travel to protect themselves or others

from a serious communicable disease,

and the airline does not provide a travel

credit or voucher. More specifically, the

loss of the value of their tickets is a

substantial harm that is not reasonably

avoidable when consumers purchased

their tickets before the declaration of a

public health emergency and the only

way to avoid the loss of the ticket value

is to disregard a medical professional’s

advice not to travel and risk inflicting

serious health consequences on

themselves. This loss is also not

reasonably avoidable when consumers

purchased their tickets before the

declaration of a public health

emergency that results in the issuance of

communicable disease-related travel

prohibition or restriction or, if there is

no declaration of a public health

emergency, before the government

prohibition or restriction for travel due

to a serious communicable disease and

the only way to avoid the loss of the

ticket value is to disregard direction

from governmental entities. Finally, this

loss of the value of their tickets is not

reasonably avoidable when the only

way to avoid the loss of the ticket value

is to disregard medical professionals’

advice not to travel and risk inflicting

serious health consequences on others.

The tangible and significant harm to

consumers of losing the value of their

ticket is not outweighed by potential

benefits to consumers or competition

because the requirement to provide

travel credits or vouchers would have

minimal, if any, impact on

nonrefundable fares. A public health

emergency affecting travel to, within,

and from the United States in a large

scale is infrequent, and this requirement

applies only to consumers who have

been advised or directed not to travel by

a medical professional or governmental

entity in relation to a serious

communicable disease.

In addition, the Department considers

it to be an unfair practice for airlines to

not provide travel credits or vouchers to

consumers who are advised by a

medical professional not to travel

because they have or are likely to have

contracted a serious communicable

disease, regardless of whether there is a

public health emergency. Infected

passengers who are unwilling to incur a

financial loss for the airline tickets may

choose to travel despite the infection,

which is likely to cause substantial

harm to other passengers on the flight

by significantly increasing the

likelihood of these passengers,

especially those seated within close

proximity of the infected passenger,

being infected by the communicable

disease. Such harm cannot be

reasonably avoided by these passengers

because they are assigned to sit close to

the infected passenger and may have no

knowledge about the infection by that

passenger. The harm to these

passengers’ health is not outweighed by

any benefits to consumers or

competition. The Department believes

there would not be any benefit to

consumers or competition among

airlines in infected or potentially

infected travelers possibly choosing to

travel by air and infecting other

passengers.

Further, the Department relies on its

authority in 49 U.S.C. 41702 to require

U.S. air carriers to ‘‘provide safe and

adequate interstate air transportation’’ to

establish the requirement that an airline

provide travel credits or vouchers to

consumers who are unable or advised

not travel due to a serious

communicable disease. This final rule

promotes safe and adequate air

transportation by reducing incentives to

travel for individuals who have been

advised against traveling because they

have or are likely to have contracted a

serious communicable disease or

individuals who are particularly

vulnerable to a serious communicable

disease by allowing them to retain the

value of their tickets in travel credits

and postpone travel.

The Department has received

comments from the airlines, ticket

agents, and their trade associations

disputing the Department’s authority to

promulgate the regulation relating to

providing travel credits or vouchers to

passengers whose travel is impacted by

a serious communicable disease. Those

comments and the Department’s

responses are provided in Section IV.1

of this rule preamble.

The requirements in this final rule

regarding airlines refunding baggage

fees when significantly delayed and

refunding ancillary service fees when

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00007 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32766

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

20

See Section 2305 of the FAA Extension, Safety,

and Security Act of 2016, Public Law 114–190 (July

15, 2016)).

21

See Section 421 of the FAA Reauthorization

Act of 2018, Public Law 115–254 (October 5, 2018).

22

A certificated air carrier is an air carrier

holding a certificate issued under 49 U.S.C. 41102.

A commuter air carrier is an air carrier as

established by 14 CFR 298.3(b) that carries

passengers on at least five round trips per week on

at least one route between two or more points

according to a published flight schedule, using

small aircraft—i.e., aircraft originally designed with

the capacity for up to 60 passenger seats. See 14

CFR 298.2. Commuter air carriers, along with air

taxi operators, operating under 14 CFR part 298 are

exempted from the certification requirements of 49

U.S.C. 41102.

23

A ‘‘ticket agent’’ is defined in 49 U.S.C.

40102(a)(45) to mean a person (except an air carrier,

a foreign air carrier, or an employee of an air carrier

or foreign air carrier) that as a principal or agent

sells, offers for sale, negotiates for, or holds itself

out as selling, providing, or arranging for, air

transportation.

24

Air transportation means foreign air

transportation, interstate air transportation, or the

transportation of mail by aircraft. See 49 U.S.C.

40102 (a)(5).

the paid for services are not provided

are specifically required by statute. The

requirement for airlines to refund fees

for checked bags that are significantly

delayed is issued pursuant to the

Department’s authority in 49 U.S.C.

41704 note, which was enacted as part

of the FAA Extension Act (Pub. L. 114–

90) and requires the Department to

promulgate a regulation that mandates

that airlines refund checked baggage

fees to passengers when they fail to

deliver checked bags in a timely

manner.

20

The requirement to refund

ancillary fees for air travel related

services that passengers paid for but did

not receive is issued pursuant to the

Department’s authority in 49 U.S.C.

42301 note prec., which was enacted as

part of the FAA Reauthorization Act of

2018 (Pub. L. 115–254) and requires the

Department to promulgate a rule that

mandates that airlines promptly provide

a refund to a passenger of any ancillary

fees paid for services related to air travel

that the passenger does not receive.

21

Comments and Responses

I. Refunding Airline Tickets for

Cancelled or Significantly Changed

Flights

1. Covered Entities, Flights, and

Consumers

The NPRM: The existing requirement

under 14 CFR 259.5 for carriers to adopt

and adhere to a customer service plan,

which includes a commitment to

provide prompt ticket refunds to

passengers when a refund is due,

applies to all scheduled flights of a

certificated or commuter air carrier

22

if

the carrier operates passenger service

using any aircraft originally designed to

have a passenger capacity of 30 or more

seats, and to all scheduled flights to and

from the United States of a foreign

carrier if the carrier operates passenger

service to and from the United States

using any aircraft originally designed to

have a passenger capacity of 30 or more

seats. The Ticket Refund NPRM

proposed to expand the applicability of

the requirement to provide prompt

refunds to a certificated or commuter air

carrier that operates scheduled

passenger service to, within, and from

the United States using aircraft of any

size, and to a foreign carrier that

operates scheduled passenger service to

or from the United States using aircraft

of any size. The Department sought

comments on whether the proposed

expansion of the regulation in section

259.5 to include smaller carriers is

reasonable, and what obstacles, if any,

these smaller carriers may encounter to

compliance.

As for ticket agents,

23

the

Department’s rule in 14 CFR 399.80(l)

requires that ticket agents of any size

‘‘make proper refunds promptly when

service cannot be performed as

contracted.’’ The Ticket Refund NPRM

proposed that, like the existing rule on

ticket agents providing refunds, the

proposed refund requirements would

apply to ticket agents of any size but

specified that it would only apply to

ticket agents that sell directly to

consumers for scheduled passenger

service to, from, or within the United

States.

In the NPRM, the Department also

considered whether the applicability of

DOT’s proposed refund requirements

should be limited to sellers of air

transportation located in the United

States and whether the beneficiaries

should be limited to aviation consumers

who are residents of the United States

based on its review of Regulation Z of

the Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau (CFPB), as codified in 12 CFR

part 1026, and the airline refund

regulation in 14 CFR part 374, which

implements the requirement of

Regulation Z with respect to airlines.

The Department recognized that the

regulated entities covered by Regulation

Z for airline ticket transactions with

credit cards may be limited to sellers

located in the United States and that the

protection afforded by Regulation Z may

be limited to consumers who are

residents of the United States with

credit card accounts located in the

United States. The Department also

noted its broad and independent

authority to prohibit unfair or deceptive

practices in air transportation or sale of

air transportation,

24

which enables it to

cover flights to, within, and from the

United States, irrespective of whether

the consumer holding reservations on

those flights is a resident of the United

States, whether the seller of the airline

ticket is located in the United States, or

whether the transaction takes place in

the United States. The Department

asked for comment on the applicability

of the proposed requirement.

The Department also sought

comments on applicability of the rule to

certain flight segments between two

foreign points if they are on the same

itinerary or ticket with flights to, from,

or within the United States. If adopting

the same itinerary/ticket standard, the

Ticket Refund NPRM asked whether the

refund requirement should only apply

when the entire itinerary/ticket is sold

under a U.S. carrier’s code or whether

it should also apply to itineraries/tickets

that combine flight segments sold under

a U.S. carrier’s code and flight segments

sold under a foreign carrier code

pursuant to an interline agreements.

Comments Received: The Department

received one comment from an

individual stating that including small

carriers operating flights to, from, or

within the United States solely using

aircraft originally designed to have a

passenger capacity of fewer than 30

seats in these regulatory proposals

would place a considerable burden on

these carriers, potentially drive many of

the smaller carriers that provide access

to more remote and distant parts of the

country out of business. The

Department received no comments on

the proposed scope of covered ticket

agents in the Ticket Refund NPRM,

which incorporates the current scope of

ticket agents refund rule in 14 CFR

399.80(l), and the definition for ‘‘ticket

agent’’ in 49 U.S.C. 40102(a)(45).

For the covered tickets/itineraries/

flights under the Ticket Refund NPRM,

IATA and several foreign carriers raised

two concerns. First, they suggested that

applying the rule to all scheduled flights

to, from, or within the United States is

incompatible with regulations from

other jurisdictions such as the European

Union and Canada. They further argued

that the rule should only apply to flight

segments departing a U.S. airport. Air

Canada argued that the scope of the

refund regulation, as proposed, would

cause confusion as refund rules in other

jurisdictions typically apply to

itineraries departing that jurisdiction to

a foreign destination. Air Canada

contended that the Department’s

proposal represents a misalignment

with Canada’s Air Passenger Protection

Regulations (APPR) when both sets of

rules apply to the same itinerary. Air

Canada provides an example that in the

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00008 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32767

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

25

As support for its position, Air Canada

references Article 12.1 of the Air Transport

Agreement Between the Government of Canada and

the Government of the United States, which states

‘‘While entering, within, or leaving the territory of

one Party, its laws and regulations relating to the

operation and navigation of aircraft shall be

complied with by the other Party’s airlines.’’

26

https://otc-cta.gc.ca/eng/publication/

application-air-passenger-protection-regulations-a-

guide.

27

Foreign air transportation ‘‘means the

transportation of passengers or property by aircraft

as a common carrier for compensation, or the

transportation of mail by aircraft, between a place

in the United States and a place outside the United

States when any part of the transportation is by

aircraft.’’ See 49 U.S.C. 40102(a)(23).

case of uncontrollable event such as

winter storm causing a cancellation, the

APPR only requires a carrier to refund

if the carrier is not able to rebook the

passenger within 48 hours from the

departure time, whereas the

Department’s proposed rule would

require a refund offer upon flight

cancellation. Second, IATA and several

foreign carriers objected to applying the

rule to certain flight segments between

two foreign points, raising

extraterritoriality concerns. Air Canada

argued that the Department’s attempt to

apply its refund rule extraterritorially

would violate the longstanding

principles of comity and reciprocity of

international aviation agreements and

the bilateral air transport agreement

25

between the United States and Canada.

Consumers and their representatives

are largely in support of a broad scope

of the Ticket Refund NPRM. Travelers

United stated that the European

regulation, EU261, applies to the

scheduled flights of all carriers

departing the European Union to the

United States but only applies to the

scheduled flights of EU carriers

departing the United States to the

European Union. Travelers United

pointed out that, as such, a consumer

traveling from the United States to the

European Union on a flight by a U.S.

carrier, for example, would not be

protected by EU 261. Some individual

consumer commenters argued that the

Department’s refund rule should cover

flights between two foreign points in the

same itinerary to streamline the refund

process for international travel.

Ticket agents also commented on the

scope of itineraries/tickets covered by

the Ticket Refund NPRM. Travel

Management Coalition suggested that

the refund rule should apply only to

ticket transactions with a point of sale

in the United States. Travel Technology

Association (Travel Tech) echoed the

‘‘point of sale’’ approach and added that

this approach is a bright-line and widely

used industry standard as the Global

Distribution Systems (GDSs) denote the

point of sale on all their ticket

transactions. Travel Tech suggested that

this approach would make the

implementation of any final rules easier

for the regulated entities.

U.S. Travel Association stated that the

refund requirement should be limited to

flights to, from, or within the United

States purchased by consumers residing

in the United States. It argued that this

approach is consistent with CFPB’s

interpretation of Regulation Z and the

Department’s proposed rule on

Transparency of Ancillary Fees, which

proposes that the consumer protection

measures relating to disclosure apply to

websites ‘‘marketed to United States

customers’’ and ‘‘tickets purchased by

consumers in the United States.’’

DOT Response: The Department has

determined that it is appropriate to

include within the scope of covered

carriers with respect to the ticket refund

requirements U.S. and foreign air

carriers operating scheduled flights to,

from, or within the United States solely

using aircraft originally designed to

have a passenger capacity of fewer than

30 seats. The Department notes that the

new ticket refund regulations in part

260, which provide clarity on various

issues related to refunds, do not add

new burdens to these carriers as they are

already covered under 14 CFR part 374

with respect to refunds for credit card

purchases. The applicability provision

in 14 CFR 374.2 states that ‘‘this part is

applicable to all air carriers and foreign

air carriers engaging in consumer credit

transactions.’’ Also, the Department’s

Office of Aviation Consumer Protection

has for many years interpreted 49 U.S.C.

41712 as requiring all carriers to provide

prompt refunds when due irrespective

of the form of ticket purchase payment.

The Department has carefully

considered airlines’ argument that the

proposed scope of covered flights for

airline ticket refunds (i.e., scheduled

flights to, from, or within the United

States) would potentially result in some

flights being subject to refund rules of

multiple jurisdictions, causing

complexity to carriers’ compliance and

potential consumer confusion. The

Department is not convinced that any

potential compliance complexity or

consumer confusion arising from these

situations cannot be addressed by

carriers offering all the accommodations

required by the applicable regulations

so consumers can choose the option that

best suits their needs. For instance, the

Department does not see any conflict of

law in the example provided by Air

Canada. APPR, which applies to all

flights to, from, and within Canada,

26

requires airlines to provide a passenger

affected by a cancellation or a lengthy

delay due to a situation outside the

airline’s control with a confirmed

reservation on the next available flight

that is operated by the carrier or a

partner airline, leaving within 48 hours

of the departure time indicated on the

passenger’s original ticket; if the airline

cannot provide a confirmed reservation

within this 48-hour period, it will be

required to provide, at the passenger’s

choice, a refund or rebooking. Both the

APPR requirement and the Department’s

refund requirement would apply to a

flight between the United States and

Canada. Under the regulation finalized

here, the carrier would be required to

refund the affected passenger if the

flight is cancelled or delayed for more

than six hours and the consumer rejects

the alternative offered or an alternative

is not offered. In this situation, the

carrier would be expected to offer the

passenger the choice of a refund and a

choice of rebooking on a flight departing

within 48 hours if such flight exists.

Providing consumers such choices

would satisfy the requirements of both

U.S. and Canadian regulations.

The Department notes that airlines

operating international air

transportation are subject to rules from

multiple jurisdictions in many other

areas, such as oversales and disability.

The Department does not believe there

is a conflict of law in ticket refunds

which makes it impossible for carriers

to comply with laws of multiple

jurisdictions. The Department expects

that U.S. and foreign air carriers

operating scheduled flights to, from, and

within the United States will fully

comply with the refund regulations to

which they are subject, consistent with

the bilateral agreements between the

United States and other countries. Such

compliance will result in consumers

benefiting from having more choices

when their flights are canceled or

significantly changed by airlines.

We have also considered the

comments on the scope of ‘‘air

transportation’’ for tickets that include

flight segments between two foreign

points. The Department has determined

that the refund requirements would

cover these flight segments that are on

a single ticket/itinerary to or from the

United States without a break in the

journey. Congress has authorized the

Department to prevent unfair or

deceptive practices or unfair methods of

competition in ‘‘air transportation,’’ 49

U.S.C. 41712(a), and ‘‘air

transportation’’ is defined to include

‘‘foreign air transportation.’’

27

The

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00009 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32768

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

28

See definitions for common terms in air travel

at https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/

files/docs/Common%20Terms%20in%20Air%20

Travel.pdf.

Department has concluded that ‘‘foreign

air transportation’’ includes journeys to

or from the United States with brief and

incidental stopover(s) at a foreign point

without breaking the journey. We

believe this approach fully addresses

the extraterritoriality concerns raised by

some carriers and is consistent with the

Department’s general approach adopted

in this final rule of considering

domestic segments of international

itineraries as a part of the international

journey. While the Department is not

providing an exhaustive list of what a

stopover that would break the journey

is, it is setting an outer limit by treating

any deliberate interruption of a journey

at a point between the origin and

destination that is scheduled to exceed

24 hours on an international itinerary to

be a break in the journey.

28

Besides this bright-line outer limit, to

determine whether a stopover under 24

hours at a foreign point breaks the

journey between a point in the United

States and a point in a foreign country,

the Department would view factors

including whether the whole itinerary

was purchased in one single transaction,

whether the segment between two

foreign points is operated or marketed

by a carrier that has no codeshare or

interline agreement with the carrier

operating or marketing the segment to or

from the United States, and whether the

stopover at a foreign point involves the

passenger picking up checked baggage,

leaving the airport, and continuing the

next segment after a substantial amount

of time.

The Department has also determined

that it is appropriate to apply the refund

and other consumer protection

regulations finalized here to all tickets/

itineraries to, from, or within the United

States regardless of the point of sales or

the residency of the consumers. While

recognizing that Regulation Z applies

only to credit card transactions that take

place in the United States involving

residents of the United States, the

Department’s authority to prohibit

unfair or deceptive practices in air

transportation under 49 U.S.C. 41712

goes beyond this scope with respect to

the type and location of the transactions

and the residency of consumers. The

Department has made the policy

decision to exercise its broad authority

under section 41712 to ensure that its

ticket and ancillary service fee refunds

requirements and the protections for

passengers affected by a serious

communicable disease provide the

maximum protections to consumers as

permitted by the law. The Department

also believes that this broad scope

would simplify and streamline the

refund process by the regulated entities

and reduce consumer frustration and

confusion.

2. Need for a Rulemaking

The NPRM: The NPRM is intended to

prevent unfair or deceptive practices by

airlines and ticket agents when airlines

cancel or make significant changes to

flights. Under the Department’s existing

regulations, airlines have an obligation

to provide prompt refunds when

refunds are due, but a specific reference

to refunding airfare due to a canceled or

significantly changed flight is not

codified in the regulations. Also, today,

airlines are permitted to adopt their own

standards for ‘‘cancellation’’ and

‘‘significant change,’’ which has

resulted in lack of consistency from

airline to airline and passenger

confusion about their rights, particularly

during periods of significant air travel

disruptions such as the COVID–19

pandemic when refund requests

overwhelmed the industry. As noted in

the NPRM, the Department received a

significant number of complaints

against airlines and ticket agents for

refusing to provide a refund or for

delaying processing of refunds during

the COVID–19 pandemic. In issuing the

NPRM, the Department explained that

its existing regulations on refunds made

it difficult to monitor compliance and

enforce refund requirements and

described benefits of strengthening

protections for consumers to obtain a

prompt refund when airlines cancel or

significantly change flight schedules.

Comments Received: Virtually all

consumers and consumer rights

advocacy groups that commented on the

NPRM are in support of the Department

exercising its legal authority under

section 41712 to codify the

Department’s longstanding enforcement

policy requiring airlines and ticket

agents to provides refunds when airlines

cancel or make a significant change to

a flight itinerary. They also strongly

support the proposal to define

‘‘cancellation’’ and ‘‘significant change’’

to eliminate the inconsistencies among

airline policies that are the main sources

of consumer frustration. FlyersRights

commented that some airlines’ behavior

during the COVID–19 pandemic to

retroactively extend the length of delay

that would qualify affected consumers

for a refund is strong evidence for the

need of rulemaking. In addition to

supporting the proposals in this area,

approximately 500 individual

consumers expressed their view that the

NPRM does not go far enough in terms

of consumer protection, with over 300

commenters explicitly suggesting that

the Department adopt regulation

mandating airlines to compensate

consumers for incidental costs (e.g.,

meals, hotels, ground transportation)

associated with airline cancellations or

significant changes, similar to the

European Union Regulation EC261/2004

(EC261). National Consumers League

noted that this additional consumer

protection measure would mitigate

consumer inconveniences and

incentivize airlines to invest in

maintaining operations according to the

published schedules.

Among airline commenters, A4A

expressed support for codifying the

refund policy and adopting definitions

for ‘‘cancellation’’ and ‘‘significant

change’’ but disagreed with some

components of the proposed definitions.

The National Air Carrier Association

(NACA) stated that the Department

should simply codify the current policy

without adopting definitions for

‘‘cancellation’’ and ‘‘significant

change.’’ IATA and several airline

commenters asserted that it is not

necessary to promulgate a new rule

because airlines were already providing

refunds pre-COVID–19 pandemic, as

evidenced by the relatively small

numbers of complaints on refunds at

that time. They contended that the

Department should not rely on a once-

in-a-lifetime event (i.e., the COVID–19

pandemic) as the justification for a

rulemaking. They pointed out that

airlines have issued unprecedented

amounts of refunds during the

pandemic and in cases where they

failed to do so, the Department’s

enforcement actions under the current

rule have proven that rulemaking is

unnecessary. IATA’s comment

recognized that standardizing

definitions would provide consistency

in passenger experiences and avoid

consumer confusion, although it argued

that allowing airlines to define these

terms provides greater flexibility, fosters

competition, and helps maximize value

for consumers. The Association of Asian

and Pacific Airlines (AAPA) expressed

its view that the refund requirement

should exempt situations where

cancellations and significant changes

are caused by safety or security-related

reasons including pandemics and when

large scale disruptions or ‘‘force

majeure’’ such as unannounced border

closures and restrictions by

governments occur.

Ticket agents and their trade

associations are generally in support of

the proposals on codification of the

refund enforcement policy and adopting

VerDate Sep<11>2014 20:43 Apr 25, 2024 Jkt 262001 PO 00000 Frm 00010 Fmt 4701 Sfmt 4700 E:\FR\FM\26APR3.SGM 26APR3

ddrumheller on DSK120RN23PROD with RULES3

32769

Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 82 / Friday, April 26, 2024 / Rules and Regulations

29

See, Rights of Airline Passengers When There

Are Controllable Flight Delays or Cancellations,

https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgenda

ViewRule?pubId=202304&RIN=2105-AF20.

definitions for ‘‘cancellation’’ and

‘‘significant change.’’ Many ticket agent

commenters share the Department’s

view that these proposals mitigate

consumer confusion caused by different

airline refund policies and enhance

predictability regarding refund rights.

However, U.S. Travel Association, an

organization representing various

components of the U.S. travel industry,

including some ticket agents, opposed

the proposals on refunds due to airline

cancellation and significant change,

arguing that the proposals do not

address the root causes of flight delays

and cancellations and would have

unintended consequences of higher

costs for travel and reduced options for

consumers.

The Department also received a joint

comment by 32 State Attorneys General

supporting the Department’s proposal

but also urging, among other things, that

the Department: (1) work on a

partnership with States to enforce

consumer protection rules, (2) require

airlines to sell tickets only for flights

they have adequate staff to operate, (3)

impose significant penalties for airline

cancellations or lengthy delays not

caused by weather or other unavoidable

reasons, and (4) require airlines to

compensate consumers affected by

cancellations or delays, including

compensating for the cost of meals,

hotels, flights on another airline, rental

cars, and issuing partial refunds to

consumers who took the alternative

flight that is later, longer, or otherwise

of less value.

The Department’s Aviation Consumer