Portions of this article were adapted from “Ranchers Agricultural Leasing Handbook” by the authors.

FARM AND RANCH LEASES

TIFFANY DOWELL LASHMET, Amarillo

Texas A&M Agrilife Extension Service

Co-author:

SHANNON L. FERRELL, ESQ., J.D., Stillwater, OK

Associate Professor, Agricultural Law

Oklahoma State University Department of Agricultural Economics

State Bar of Texas

12

TH

ANNUAL

JOHN HUFFAKER AGRICULTURAL LAW COURSE

Lubbock – May 24-25, 2018

CHAPTER 6

TIFFANY DOWELL LASHMET

Assistant Professor & Extension Specialist

Texas A&M Agrilife Extension Service

6500 Amarillo Blvd. West

Amarillo, TX 79106

806-677-5668

Tiffany Dowell Lashmet is an Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist in Agricultural Law with Texas A&M

Agrilife Extension. She focuses her work on legal issues affecting Texas agricultural producers and landowners

including agricultural leases, water law, oil and gas law, eminent domain, easements, and landowner liability. She

serves on the Board of Directors for the American Agricultural Law Association and is part of the State Bar of Texas

John Huffaker Agricultural Law Course Planning Committee. In 2016, Tiffany was named the State Specialist of the

Year for Texas Agriculture by the Texas County Agricultural Agents Association.

Tiffany grew up on a family farm and ranch in Eastern New Mexico, received her Bachelor of Science in Agribusiness

(Farm and Ranch Management) summa cum laude at Oklahoma State University, and her law degree summa cum

laude at the University of New Mexico. Prior to joining Texas A&M Agrilife Extension, Tiffany worked for 4 years

at a law firm in Albuquerque practicing civil litigation. She is licensed to practice law in New Mexico and Texas. She

lives in the Texas Panhandle with her husband, Ty, and her children Braun and Harper.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1

II. TEXAS A&M AGRILIFE EXTENSION LEASE EDUCATION ......................................................................... 1

III. SETTING LEASE RATES ..................................................................................................................................... 1

A. Cash Versus Crop Share Lease Arrangement.................................................................................................. 1

1. Cash Rental Agreements ......................................................................................................................... 1

2. Share Rental Agreements ........................................................................................................................ 2

B. Published Texas Lease Rate Information ........................................................................................................ 2

1. Texas A&M Agrilife Extension Resources ............................................................................................. 2

2. USDA – NASS Survey Reports .............................................................................................................. 3

3. Texas Rural Land Value Trends .............................................................................................................. 3

C. Setting a Cash Lease Rate for Farmland ......................................................................................................... 3

1. Cash-Rent Market Approach ................................................................................................................... 3

2. Landowner’s Ownership Cost Approach ................................................................................................. 4

3. Landowner’s Adjusted Net-Share Rent Approach .................................................................................. 4

4. Operator’s Net Return to Land Approach ............................................................................................... 4

5. Percent of Land Value Approach ............................................................................................................ 4

6. Percent of Gross Revenue Approach ....................................................................................................... 4

7. Dollars per Bushel of Production Approach ............................................................................................ 5

8. Fixed Bushel Rent Approach ................................................................................................................... 5

9. Flexibility in Cash Leases ........................................................................................................................ 5

10. Combining the Methods to Calculate a Fair Cash Rent........................................................................... 5

D. Setting Shares under a Share Rental Agreement ............................................................................................. 5

1. Variable expenses that increase yields should be share in the same percentage

as the crop is shared. ................................................................................................................................

5

2. Share arrangements should be adjusted to reflect the effect new technologies

have on relative costs contributed by both parties. .................................................................................. 6

3. The landlord and tenant should share total returns in the same proportion as

they contribute resources. ........................................................................................................................ 6

4. Tenants should be compensated at the termination of the lease for the undepreciated

balance of long-term investments they have made. ................................................................................. 6

5. Good, open, honest communication should be maintained between the landowner and tenant. ............. 6

E. Setting a Lease Rate for Range Land .............................................................................................................. 7

IV. GRAZING LEASE CHECKLIST .......................................................................................................................... 8

V. FARM LEASE CHECKLIST ............................................................................................................................... 12

VI. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................................................................... 16

APPENDIX I................................................................................................................................................................. 17

APPENDIX II ............................................................................................................................................................... 19

APPENDIX III .............................................................................................................................................................. 25

APPENDIX IV .............................................................................................................................................................. 27

APPENDIX V ............................................................................................................................................................... 29

APPENDIX VI .............................................................................................................................................................. 31

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

1

FARM AND RANCH LEASES

I. INTRODUCTION

Leasing agricultural land is common across Texas.

Many producers have leased farm or ranch land for

decades and even for generations. Leasing offers

benefits to both the landowner and tenant. For

landowners, lease payments can serve as an added

income source. It is a particularly attractive option for

absentee landowners who may want to the land to

remain in agricultural production, but are not in a

position to farm or ranch it themselves. For tenants, the

option of a lease allows them to expand their operation,

but avoid the financial commitment that comes with

purchasing property. This strategy is frequently utilized

by younger operators getting started in the farming or

ranching business.

II. TEXAS A&M AGRILIFE EXTENSION

LEASE EDUCATION

Recognizing the need for educational information

on this topic, Texas A&M Agrilife Extension developed

a program for landowners and drafted a handbook, the

Ranchers Agricultural Leasing Handbook to provide

information to landowners and tenants alike related to

the legal issues surrounding agricultural leases. Over the

past three years, we have held eight Ranchers Leasing

Workshops across Texas and had over 400 participants

attend. Of those, the vast majority, over 75%, are

landowners. Through evaluations, we determined that

over 1/3 of attendees have only oral lease agreements.

Of those with lease agreements, both farm and ranch,

nearly all were structured on a cash basis. Only 7% of

respondents with leases had a crop share lease and only

3% had a flex lease structure in place.

III. SETTING LEASE RATES

Determining how best to structure a lease and what

rate to charge is one of the most important decisions

facing tenants and landowners.

A. Cash Versus Crop Share Lease Arrangement

Traditionally, rental agreements fell into two

categories: a “cash rent” arrangement in which the

tenant paid a specific dollar amount in rent or a “share

rent” arrangement in which the tenant gave the landlord

a share of the crop produced from the land (usually with

the landlord and tenant sharing in the input costs for

growing the crop). Recent years have seen the

development of many varieties of these two basic

arrangements. Before committing to either category of

arrangements, though, both landlords and tenants need

to consider the potential advantages and disadvantages

of each arrangement.

1. Cash Rental Agreements

Cash rental arrangements are generally considered

the most straightforward rental arrangements since the

tenant makes a pre-determined lease payment on a

regular basis, and the landlord provides little or no input

into the management decisions for the land during the

period of the lease. Even in a cash rental agreement,

though, there are a number of considerations to ponder

for both landlord and tenant.

a. Advantages of Cash Renting for Landlords

Perhaps the most easily-identified advantage of

cash rental agreements for landlords is their simplicity.

As mentioned above, the landlord does not have to

involve him- or herself in production or marketing

decisions. This can be an important advantage for a

landlord with little or no experience in operating

agricultural land (note, though, that this does not mean

the landlord should be uninterested in the management

of the property and just wait on the “mailbox money” to

come in). Fixed cash rental payments also shifts

virtually all of the price, cost, and production risk of the

crop to the tenant, leaving the landlord only with the

financial risk of the tenant’s ability to pay. Landlords

relying on lease payments to support them in retirement

may find this an important benefit. Further, income

under fixed cash rental arrangements is not considered

self-employment income (and thus is not subject to self-

employment tax) and does not reduce Social Security

benefits if the landlord is retired.

b. Disadvantages of Cash Renting for Landlords

Although cash rental agreements can be simple,

determining a rental rate can be difficult, as discussed

below. Further, once that rate is set, psychological

factors may make it difficult to change the rate even

though a number of market forces may suggest a change

is needed. The transfer of risk to the tenant means the

tenant not only bears “downside” risk (risk that input

costs might increase, commodity prices might decrease,

or that production may be low) but that they get all the

advantages of “upside” risk (input costs decrease,

commodity prices increase, or production increases).

There may also be fewer alternatives for tax

management compared to a share lease (the reason for

this is discussed below with share rental agreements).

Finally, there are some incentives for tenants to “mine”

the land’s nutrients – especially under a short-term lease

– since the tenant’s profits under a fixed cash lease come

from increasing yields while minimizing costs such as

fertilizer or soil amendments. However, longer term

leases and well-written leases can significantly reduce

these risks.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

2

c. Advantages of Cash Renting for Tenants

Tenants in a cash rental agreement have significant

freedom in their management decisions, since there is

little or no requirement for management input from the

landlord. The pre-determined nature of the rental

payment makes that cost of operation fixed, which

provides more stability in projecting costs for the year(s)

ahead. Since they bear the majority of risk in

production, the tenant can reap all the “upside” risk in

crop production if prices and/or production conditions

are favorable.

d. Disadvantages of Cash Renting for Tenants

Bearing virtually all of the risk in a cash rental

arrangement, the tenant may have difficulty making

rental payments if economic conditions have been

difficult. Psychologically, even if conditions have been

difficult for a number of consecutive years, landlords

may not adjust rental rates downward. Finally, the

tenant faces the cash-flow issues of bearing all costs of

crop inputs (compared to a share arrangement where the

landlord participates in the purchase of crop inputs).

2. Share Rental Agreements

In a share rental agreement, the landlord and the

tenant are both actively involved in the production of the

crop. Both parties participate in the management

decisions and the costs of growing and marketing the

crop. The rent paid is a proportion of the crop produced,

which can be paid either by turning over part of the

physical commodity itself or paying the landlord that

proportion of the revenue from the sale of the crop by

the tenant.

a. Advantages of Share Renting for Landlords

Share rental agreements naturally result in the

sharing of risk between the landlord and tenant. As a

result, the benefits of a “good year” are shared by both

parties. This enables the landlord to capture some of the

“upside risk” involved in production. If the landlord is

an experienced producer, they can use that experience to

aid the tenant in management decisions, which

hopefully increase the returns to the landlord. Since the

landlord is actively involved in the agricultural

operation of the land, they can use that participation to

build Social Security base since their income from the

rent is subject to self-employment tax, and the landlord

can also take advantage of Internal Revenue Code

Section 179 depreciation on capital investments made in

the agricultural operation.

b. Disadvantages of Share Renting for Landlords

Risk of a “bad year” means the landlord’s returns

are subject to the same variability as those of the tenant.

This can mean share leases may provide too much risk

for landlords depending on rents for their primary

source of income. Depending the nature of the

landlord’s involvement, the income from the lease may

also reduce the amount of Social Security benefits for

which the landowner is eligible if he or she is retired.

The amount of involvement required for a share lease

agreement may also make these agreements unsuitable

for landlords without significant experience in operating

a farm or ranch.

c. Advantages of Share Renting for Tenants

Perhaps the two greatest advantages of a share

rental agreement for tenants is the reduction in operating

capital requirements and the sharing of risk with the

landlord. Since the landlord and tenant both share in the

operating costs of the land, the tenant is not required to

finance the entire cost of those inputs as he or she would

be under a fixed cash rental agreement. Similarly, the

cost of rent is reduced (in cash equivalent terms) in

“bad” years. The ability to tap into the expertise of the

landlord through shared management decisions can be

another important advantage, particularly for beginning

producers.

d. Disadvantages of Share Renting for Tenants

The risk-sharing features of a share rental

agreement means the tenant has less ability to capture

“upside” risk since that upside must be shared with the

landlord. Determining and delivering shares also

involves more work on the part of the tenant since he or

she may have to make multiple deliveries of product to

multiple locations. Finally, the management input of the

landlord may conflict with the desired decisions of the

tenant.

B. Published Texas Lease Rate Information

One of the most frequent questions from

landowners, tenants, and attorneys working to draft

agricultural leases is what the going rate for land is in a

particular area. Of course, there is no one-size fits all

answer to this question. An agreeable lease rate for any

property will depend upon a number of factors such as

the amount and quality of forage, availability of water,

commodity prices, land values, existence of fences, and

the like. There are, however, a number of useful

sources of information related to average lease rates in

Texas.

1. Texas A&M Agrilife Extension Resources

First, Texas A&M Agrilife Extension has County

Extension Agents in every county in the state. These

agents are trained to assist Texas landowners on a

variety of issues, and helping to evaluate and set lease

rates is one of those areas. Additionally, Texas A&M

Agrilife Extension has Range Specialists and

Agronomists stationed throughout the state. These

Specialists, most of whom have a Ph.D. in Range and

Ecological Sciences or in Agronomy, are

knowledgeable about forage quality and lease rates and

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

3

can be very helpful to landowners and attorneys

analyzing the proper price for a farm or grazing lease.

Additionally, the Texas A&M Agricultural

Economics Department publishes crop and livestock

budgets for each of the various Extension Districts

across Texas. These budgets, which are broken down

not only by district, but by crop as well, include a line

item for rental costs. This number is based on average

lease rates paid for land to grow the specific crop or raise

the specific livestock for each budget. For example, the

budgets for District 1, which includes the Panhandle

include options for forage crops such as hay and silage;

field crops such as corn, cotton, and wheat (both

irrigated and dryland); and for livestock, including cow-

calf and stockers. For a cow-calf operator in District 1,

the 2018 budget includes a projected cost of $7 per acre

per year. These budgets may be found in Excel form on

the Texas A&M Agricultural Economics Department

website.

2. USDA – NASS Survey Reports

Second, the United States Department of

Agriculture – National Agriculture Statistics Service

conducts yearly surveys and publishes reports of

average lease rates throughout the country. The report

breaks rates down by state, regions with the state, and

by county. Further, lands are divided into three

categories: irrigated cropland, non-irrigated cropland,

and pastureland.

In 2017, nationwide averages were reported as

$212 per acre per year for irrigated cropland, $123 for

non-irrigated cropland, and $12.50 for pastureland. In

Texas, the average lease rates were $87 for irrigated

cropland, $28 for non-irrigated cropland, and $6.60 for

pastureland. At least every other year, NASS breaks

down this data further by reporting data by district

within a state and by county. This report is available in

September of even-numbered years. Texas is divided

into 15 districts, and average cash rent values reported

for each one. A map showing the NASS districts is

included in Appendix I, Figure 1-1.

For example, for the Northern High Plains in 2016,

cash lease rates were reported as $113 for irrigated

cropland, $22 for non-irrigated cropland, and $7.80 for

pastureland. Further, looking at Dallam County, which

is included in the Northern High Plains Region, for 2016

are $97.50 for irrigated cropland, $55.50 for non-

irrigated cropland, and $6.10 for pastureland. This type

of data is available on the USDA NASS website for

every county across the United States.

3. Texas Rural Land Value Trends

Each April, the Texas Chapter of the American

Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers

publishes a report, the Texas Rural Land Value Trends,

a report that includes an analysis of land prices

throughout the state and reports on the average range for

land lease rates. The report breaks Texas into seven

regions and each region into sub-regions and provides

land value and average lease rates for each. A copy of

the report may be downloaded from the Texas Chapter

of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural

Appraisers website.

For example, for Region 1, which includes much of

the Panhandle and South Plains, the 2016 report shows

land value ranges and rental ranges for several classes

of property: irrigated cropland (good water), irrigated

cropland (fair water), dry cropland (east), dry cropland

(west), rangeland, and Conservation Reserve Program.

For rangeland in the North Panhandle area, the report

shows a rental range that has been stable with activity at

$7 to $12 per acre. For the same area, irrigated cropland

with good water shows stable rental rates from $150 to

$250 per acre.

C. Setting a Cash Lease Rate for Farmland

Although cash rents are quite simple once

established, establishing that amount can be can be one

of the most complicated and contentious pieces of

negotiating a rental agreement. Determining the rental

rate depends not only on the local land market, but on

the land itself and the parties as well. Markets matter,

and all other things being equal, an active local market

for land will drive rental rates upward just as relatively

little demand for agricultural land will drive rental rates

down. The characteristics of the land itself, including

its soils, drainage, size, shape, location, and facilities

drive values, as do the production history of the tenant

and the lease provisions desired by the parties. All of

these factors combine in different ways to create several

different approaches to establishing a cash-rent value.

1. Cash-Rent Market Approach

The cash-rent market approach is the standard

against which all other methods are measured; if another

method yields a rental rate significantly above or below

the market rate, there should be significant justification

for that difference. This is probably the approach

coming first to mind for landowners and tenants, and

may sound like the most straightforward – simply ask

around for rates paid for similar land.

However, that simplicity can be deceptive for two

primary reasons. First, it can be difficult to get objective

information about rental rates. Rates may be subject to

exaggerations or from transactions that are not the result

of arms-length transactions between unrelated parties.

The quality of information obtained is thus very

important. Good sources of published information on

average lease rates in your area are set forth in Section

IIIB above. A good place to start are lease surveys

conducted by your state Extension service or the

National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS),

but also remember that these surveys generally present

averages of values and may not be specific to your very

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

4

local area. That leads to the second reason market data

can be deceptive – it reflects values paid for land other

than the land actually in question. Numerous

adjustments must be made from market rates to reflect

the unique traits of the land at hand.

Despite these challenges, the cash-rent market

approach should be the starting point of any rental rate

calculation. Start with the best data available, and think

carefully about any adjustments that need to be made

from the prevailing rates to take into account the

positive or negative production characteristics of the

land to be leased.

2. Landowner’s Ownership Cost Approach

The landowner ownership cost approach does just

what its name implies – calculates the cost of ownership

to the landlord – and uses that cost to determine a base

for the rental amount. Put another way, the rental

amount should at least exceed the ownership cost of the

land and provide a measure of profit to the landowner

while also providing the tenant the opportunity to make

a profit.

The first piece of information needed for this

approach is the fair-market price of the land (valued for

agricultural use, and not for some other use such as

residential development). Second, an “interest charge”

(meaning the “opportunity cost” of owning the land – in

other words, if the land were sold and placed into an

investment with similar risk, what rate of return would

it yield?) must be calculated. This is often done by using

the “rent to value” ratio reported by USDA-NASS for

various regions in the United States. Together, the price

and interest rate provide an annual charge for the land

itself. Next, the real estate taxes paid on the land by the

landowner are incorporated as an ownership cost.

Finally, land improvement costs such as treatments for

soil pH, building or maintaining conservation structures,

etc. are included. Adding these costs together on an

annual basis provides a starting point for the

landowner’s asking price in rents. An example of this

calculation method is included in Appendix II as Figure

2-1.

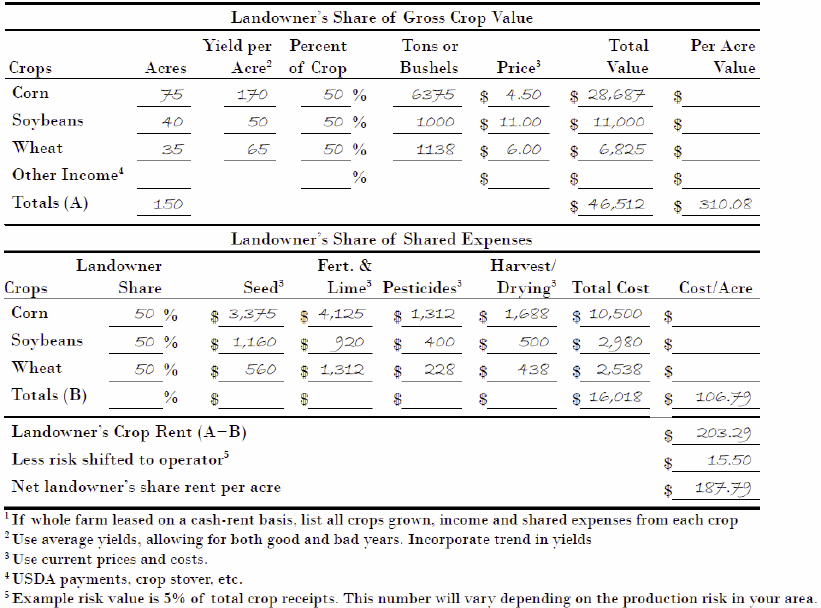

3. Landowner’s Adjusted Net-Share Rent Approach

This approach works to calculate the cash-rent

equivalent of a share lease. The general assumption is

that a cash rent should be slightly less than a share lease

amount since under a cash lease, the tenant bears almost

all the risk. To calculate a cash rent under an adjusted

net-share rent approach, the landlord and tenant must

first determine the prevailing shares for the crop in

question – these shares vary significantly from crop to

crop and region to region, and frequently occur as 1/3-

2/3 shares, 1/2-1/2 shares, or 40%-60% shares. Next,

historical data for the yields of the land in question and

for input and product costs should be gathered to

determine what the average share rent would have been

for the property. Finally, and adjustment should

probably be made to reflect the additional risk that the

tenant will take under a cash rental approach. An

example of this calculation method is included in

Appendix II as Figure 2-2.

4. Operator’s Net Return to Land Approach

The operator’s net return to land approach is

something of a counterpoint to the landowner’s

ownership cost approach in that it is a calculation of

what the tenant (or operator) can afford to pay given the

productivity of the land. This approach takes into

account the productivity of the land and the costs of

inputs, fixed costs, and returns to labor and

management. Per-acre costs are deducted from per-acre

returns to determine how much rent can be paid at a

break-even level given the assumptions made. An

example is provided in Figure 2-3 in Appendix II.

5. Percent of Land Value Approach

Perhaps the most straightforward of all the cash

rental approaches discussed here, the percent of land

value approach simply consists of calculating the

“opportunity cost” of the land. In other words, if the

landowner sold the land and invested the proceeds in a

similar investment (in the case of land, a long-term

investment with similar risks), what would that

investment yield on an annual basis? For agricultural

land, the best way of calculating an opportunity cost is

the rent-to-value ratio (the average ratio in a region of

agricultural land’s rent to the total value of the land).

The per-acre value of the land in question is then

multiplied by the “opportunity cost” interest rate – in

this example, the rent-to-value ratio – to determine the

desired per-acre rent. Note, though, that this approach

may not reflect the market realities in the area, and that

rent-to-value ratios may be slow to change over time and

thus may be further off in years where there have been

significant changes in returns to agricultural land.

Appendix II includes an example in Figure 2-4.

6. Percent of Gross Revenue Approach

Another angle of attack to determine a rental

amount would be to calculate the percent of gross

revenues a landowner would be entitled to under a share

rental agreement. This requires collection of data on the

average production of the land in question, historical

commodity prices, and the percentage of gross income

received by landowners under share leases in the region.

Note that there is an important distinction to be made in

determining the landlord’s percentages under this

method – the percentages used should be from leases in

which the tenant pays all of the input costs for the leased

land, since the landlord will be paying no input costs

under this method. An example of this calculation is

provided in Figure 2-5 of Appendix II.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

5

7. Dollars per Bushel of Production Approach

A method that can take into account the specific

productivity of a piece of land is the dollars per bushel

of production approach. With this approach, historical

rents and crop production records in the area are

reviewed to determine how much rent has been paid per

bushel of production. Once this has been calculated, the

landowner and tenant have two options: they can use the

historical average productivity of the specific parcel and

this per-bushel amount to set a rent in advance, or they

can make the rent variable based on the actual

production of the land that year (though it should be

noted that making the rent variable affects a number of

factors in the advantages and disadvantages of the lease,

as well as potentially impacting the tax implications of

the lease). A calculation example of this approach may

be found in Appendix II, Figure 2-6.

8. Fixed Bushel Rent Approach

The fixed bushel rent approach is something of a

variation on the dollars per bushel of production

approach in that the fixed bushel rent approach uses the

historical average production of the land and an agreed

price to calculate a rental rate. It also relies on

information from share rental rates in the region to

determine what share of production would be paid to the

landlord (assuming the landlord pays no other expenses

other than land). Assuming that a dollar-per-bushel

amount is fixed at the time the lease is entered, the lease

is considered to have a fixed cash rent, but if that number

is flexible, the lease is considered a variable rent, with

all that implies. Appendix II contains an example in

Figure 2-7.

9. Flexibility in Cash Leases

A common theme throughout this discussion has

been the allocation of risk to the tenant under almost all

cash rent forms. In some cases, tenants may be willing

to accept that risk allocation, but may want some

protection if either input or product prices get so far

away from averages as to make the cash rent payments

extremely difficult. By the same token, landlords may

want to take advantage of some “upside risk” when

times are exceptionally good. Thus, both parties may

want to introduce some flexibility into the lease by

providing for a baseline rate of cash rent that is adjusted

by some formula based on either input costs, product

prices, the productivity of the land, or even some

combination of all elements. A number of these

methods are discussed in the NCFMEC publications

referenced at the end of this chapter. To keep this

discussion relatively brief, any adjustments need to have

very clear triggers and calculations that can be

objectively determined by both parties. For example, if

one variable is the price of a commodity, the lease

should be very clear about both when that price is

determined (for example, at a set date, when harvest is

commenced, when harvest is completed, etc.) and how

that price is determined (by local elevator cash price, by

USDA market report, by nearby futures contract price,

etc.). Consider also that it may be inequitable for only

one party to have the benefit of flexibility – a tenant may

be uncomfortable signing a lease wherein the landlord

gets the advantage of upside risk but the tenant bears all

downside risk. Further, the more variable a lease

becomes, the more potential tax implications are

triggered and the more the lease looks like a share lease.

At some tipping point, a share lease may be more

desirable.

10. Combining the Methods to Calculate a Fair Cash

Rent

This discussion examined a number of methods

used to calculate a cash rent amount. Which method is

the right one? The answer might be one, more, or all of

them. Neither landlord nor tenant may have the time or

resources to pull together the information needed to

calculate a rental rate under all the methods, but

calculating two or more methods might help both parties

get some different perspectives on what a fair rental

amount could be. Additionally, calculating the rent

under different methods can trigger some important

insights – if all of the methods used arrive at roughly

similar amounts, it is a strong suggestion that a rent in

that range is fair to the parties. If one or more methods

are sharply different, it may be cause to examine why

those differences arise, as they may indicate something

about the market or the land that justifies a different

lease rate.

Discussing the calculation methods can not only

help landlord and tenant arrive at a mutually-agreeable

rental rate, but can also help them discuss the risk factors

faced by both, which can lead to a better rental

agreement itself.

D. Setting Shares under a Share Rental Agreement

At a fundamental level, share leases focus on

sharing both the costs of operating the agricultural land

and the profits from its production. This means both

upside and downside risk are shared by the parties as

well. But how does one set the appropriate shares to be

paid and received by landlord and tenant? The North

Central Farm Management Extension Committee has

proposed five principles to help set shares:

1. Variable expenses that increase yields should be

share in the same percentage as the crop is shared.

The principles of agricultural economics

demonstrate that using this principle will make sure the

incentives for both the landlord and the tenant will guide

them to use the most efficient levels of inputs.

Conversely, not following this principle will create

incentives for one party to use too much of an input to

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

6

capture more revenue while shifting costs to the other

party.

2. Share arrangements should be adjusted to reflect

the effect new technologies have on relative costs

contributed by both parties.

New technologies can cause substitutions of inputs,

which can shift the economics of the lease arrangement.

For example, when a farm is shifting from conventional

tillage to a low- or no-till system, chemical weed control

may be used as a substitute for mechanical weed control

through cultivation. So, should the cost of chemical

weed control be paid by the landlord, the tenant, or

shared? Another example is seed (such as corn seed)

that is frequently bundled with other inputs such as

herbicide, insecticide, and perhaps even fertility

products. If the seed product affects the need for other

inputs, who should pay for the seed? The answers to

these questions depend on the nature of the substitution.

• If the input is a yield-increasing input, the

landowner and operator should share the costs in

the same proportion as the crop is shared, as

discussed in principle 1.

• If the input is a true substitution, the party

responsible for the item substituted in the original

lease should pay for the input.

• If the input is both yield-increasing and a

substitute, the lease needs to address this situation

after discussion of how the cost should be shared

by the parties.

3. The landlord and tenant should share total returns

in the same proportion as they contribute resources.

This principle sounds simple, but may be the most

complex to implement. The parties have to discuss and

determine the value of what each is “bringing to the

table,” so to speak. The landlord is contributing the

production asset, land, and the tenant is likely

contributing the majority of operating labor and

machinery expense. Both contribute management and

bear risk. In many cases, the operator’s primary costs

(labor and machinery) are largely the same whether

dealing with high-quality or low-quality land, but other

input costs may vary considerably. For this reason,

shares on high-quality land and/or crops with high

variable input costs tend to be more equal, whereas

shares on lower-quality land and/or crops with low

variable input costs tend to be place larger share values

with the tenant, as illustrated below.

4. Tenants should be compensated at the termination

of the lease for the undepreciated balance of long-

term investments they have made.

In some cases, the parties may need to invest in

inputs whose lives could extend beyond the life of the

lease, such as perennial seeds (alfalfa, for example), pH

amendments to the soil such as lime, and tiling or other

soil drainage. A tenant will likely be unwilling to share

in those costs if they are not assured of having access to

the land for the entirety of the inputs’ productive life.

Thus, it may be wise to include lease language that

guarantees the tenant will receive back the

undepreciated share of their investment if their lease is

terminated before the end of the investment’s life.

5. Good, open, honest communication should be

maintained between the landowner and tenant.

Communication is vital in any productive lease

arrangement, but it is even more important in a share

leasing arrangement, since the parties must share in

many of the decisions made in the course of agricultural

operations on the leased land. Frequent communication

between the parties can do much to provide

transparency and to make both parties feel that their

concerns have been acknowledged and understood by

the other.

Subject to these two principles, the first step in

determining what shares would be equitable for the

leasing arrangement is to form a thorough crop budget

for the land in question. The items in the budget will do

a great deal to show the value to be contributed by each

party, which in turn will help determine the equitable

balance of shares for the lease. As noted above in

Section III(B)(1), Texas A&M Agrilife Agricultural

Economics Department offers sample budgets, which

can be customized as needed, on their website. Items

that should be considered when formulating a budget

include:

• Land: The land in question should be valued at its

fair market value in agricultural use; non-

agricultural uses (such as residential development

or recreational uses) should be ignored since they

are not relevant to the crop enterprise for the

purposes of the budget.

• Interest on land: As discussed above, the usual

value placed on land interest (“opportunity cost”)

for the purposes of lease budgeting is the rent-to-

value ratio for the area. One way of determining a

land cost for the purposes of the crop budget is to

multiply the land value by the rent-to-value ratio.

• Cash rent on land: Cash rent on land can also be a

valid measure for the value of the land contributed

to the lease. Here, cash rent represents the cost that

would be incurred if the parties had to lease the

land on a cash basis.

• Real estate taxes: Real estate taxes can be a

carrying cost of land, but be careful not to include

this value twice, since it is likely imputed to the

values for cash rental rates or on interest on land.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

7

• Land development: The average cost per year for

lime, conservation practices, and other

improvements are another land cost. Use caution

with these costs to avoid double-counting just as

with real estate taxes, though, as they too are often

included in cash rental rates.

• Crop machinery: The machinery charges should be

the average value of a good line of machinery

needed to farm the land in question, which is not

necessarily the same as the value of new

machinery.

• Depreciation: Use a market rate of depreciation for

machinery (often 8 to 12 percent of the average

value annually), not a tax-based depreciation rate –

tax rates are often far higher and will result in an

over-charge of the machinery cost.

• Machinery repairs, taxes, and insurance: Research

data suggests annual repairs average between 5 to

8 percent of the machinery’s original value. Taxes

and insurance costs can be obtained from actual

costs in farm records.

• Machinery interest: The prevailing local interest

rate for machinery loans (or operating capital

loans) can be used to determine the opportunity

cost for machinery).

• Custom rates: Rates for activities that the parties

intend to hire out, such as fertilizer application or

harvesting can be entered using bids from local

providers.

• Irrigation equipment, depreciation, repairs, taxes,

insurance, and interest: These costs for irrigation

systems can be determined and calculated in much

the same fashion as machinery costs, as discussed

above.

• Labor: Labor may be contributed solely by the

tenant, or may be joint between the tenant and

landlord. However, the contribution of significant

labor by the landlord can make the share lease look

much more like a joint venture or partnership, and

that may not be the desired legal outcome of the

parties. When valuing labor, use prevailing wage

rates for comparable agricultural labor in the area.

Note that the value contributed by the management

skills of the tenant may make them far more

valuable than the average farm laborer in the area,

but that value is captured separately.

• Management: The management contributions of

the landlord and tenant can vary significantly

depending on their operational experience. In most

cases, management charges may simply be a

function of the bargaining power of the parties.

There are a number of ways this can be valued, but

two possible rules of thumb are:

o One rule is that management should be valued

at 1 to 2.5 percent of the average capital

managed in the business, measured as the

market value of the land, machinery, and

irrigation equipment. This rule is probably

more stable since it will not fluctuate as much

as the next rule on year-to-year basis.

o Another guide can be the management fees

charged by professional farm managers.

These managers commonly charge between 5

to 10 percent of adjusted gross receipts.

Once these costs have been compiled and a budget for

the production of the crop has been estimated, the

parties can use one of two methods to determine the

appropriate shares for landlord and tenant.

• The Contribution Approach

In the contribution approach, the percentage of

overall costs contributed by each party are

calculated, as well as those costs that are shared by

some pre-determined proportion. The remaining

costs – which should be the “yield-increasing

inputs” as discussed above – and the income should

be shared in the same proportions. Consider a

worksheet containing a corn-soybean rotation

example found in Appendix III.

In the example, the costs contributed by the

landlord equal $247.50 per acre or 53.3 percent of

the total costs, and the costs contributed by the

tenant are $216.75 or 46.7 percent of the total costs.

Note also that the worksheet has assumed that costs

for fertilizer, herbicides, and

insecticides/fungicides have not been included

since the landlord and tenant intend to share those

costs among themselves. The shares calculated

suggest something close to a 50/50 share

arrangement. With this approach, the budget has

led the way to suggested shares.

• The Desired-share Approach

Conversely, the desired share approach works

backward from a desired share arrangement. For

example, with the same corn-soybean rotation, the

parties may want to target a 50/50 share

arrangement. In such a case, they would simply

adjust their contributions so that the end result is a

50/50 share of the expenses. This approach is

much less common, but may be desirable based on

the circumstances of the parties.

E. Setting a Lease Rate for Range Land

The calculation of pasture lease rates can borrow

from a number of the principles discussed above of

leases primarily involving cropland.

As with the methods above, some homework on the

part of the landowner is involved in collecting

information on the price of land, an applicable interest

rate for the land, land taxes, land development costs

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

8

(such as conservation practices) the costs of facilities

such as pens, loading docks, etc. (and the depreciation,

interest, repairs and taxes on the same). Any labor and

management costs on the part of the landlord should also

be included.

Another important piece of information is the

desired stocking rate for the land. The long-term

productivity of the land is dependent upon maintaining

a proper stocking rate and not “over-mining” forage

species or depleting soil nutrients. Understanding how

many animal units can be grazed on the property can

help in setting guidelines for the lease in terms of

stocking rate; it can also help in selecting the method of

rent payment. For example, setting pasture rent on a

per-acre basis or share-of-gain basis creates incentives

for the tenant to over-stock the property. Thus,

restrictions on stocking rates as well as properly

calculated rent terms are important. Stocking rates can

be expressed as an average stocking number (taking into

account the fact that herd numbers may change over the

course of the lease), or can be based on animal-days or

animal-unit days.

An example cost estimate worksheet for a

landowner interested in leasing pastureland is included

in Appendix IV, Figure 4-1.

Likewise, the livestock owner must also estimate

their net returns from grazing operations on the land.

Generally, the livestock owner will estimate costs on a

per-head basis, which is likely the most useful format

since marketing revenues will also be calculated on a

per-head basis. The estimated market value of the

animal less the non-land costs of production, equals the

livestock owner’s net returns to pasture, as illustrated in

Appendix IV Figure 4-2.

As you can see from comparing the values

calculated by the landowner and tenant on the

worksheets in Appendix IV, the contributions by the

landowner are greater than the returns to grazing on the

part of the livestock owner. Thus, the landowner will

likely want a higher rate of rent than the livestock owner

is willing to pay. This means that the parties will have

to negotiate, with one or both parties taking a lower rate

of return (or otherwise, both parties would walk away

from the leasing opportunity). Below are some

examples of how a compromise can be found.

• Fixed Per-Acre or Per-Head Rent

As with crop leases, a simple fixed per-acre or per-

head rental amount could be charged. Given the

example discussed above and illustrated in

Appendix IV, the landowner would likely want at

least $27 per acre, while the livestock owner would

like to pay approximately $15 per acre. The parties

would have to negotiate for an amount somewhere

between the two values. If a fixed per-acre rent is

used, negotiated limits on stocking rates are

important to include in the lease, as discussed

above. This arrangement shifts risk away from the

landowner and to the livestock owner.

• Fixed Charge per Pound of Gain

Livestock production faces two major risks – price

risk in the amount received for the animal at

market, and the gain of the animal (production

risk). Weight gain is a function of the animal’s

inherent productivity (often dictated by the

animal’s genetics and health) and the productivity

of the pasture land. The productivity risk

associated with land (although it is also tied to the

productivity of the animal) can be shifted back

toward the landowner through a fixed charge per

pound of gain. For example, the lease could

specify a cost of $0.45 per pound of gain. Since

this arrangement does shift risk to the landowner,

they may insist on a higher rate to offset this risk.

• Share of Gain

One potential method of distributing the income

from the grazing operation is to value the

contributions made by the landlord and livestock

owner to determine the shares of that income. The

landowner and livestock owner can agree to share

this proportion of the proceeds when the livestock

are sold. Under this arrangement, the actual rental

is not known until the end of the lease when the

final value of gain is known (not unlike in a crop

share lease). An example of this calculation

method is included in Appendix IV, Figure 4-3.

IV. GRAZING LEASE CHECKLIST

The following checklist includes many of the most

common terms found in grazing lease agreements.

Certainly, the list is neither exhaustive, nor will every

term be needed in every lease agreement.

• Names of the parties: The lease should include

the name and address of the parties, both the

landowner and the lessee.

• Duration of lease: The length of the lease should

be specified with particularity and may range from

a matter of months to several years. It is important

to note that leases of certain durations may be

required to be in writing in order to be enforceable.

For example, pursuant to the Statute of Frauds,

Texas requires a lease of real property lasting for

more than 1 year to be in writing. See Texas

Business & Commerce Code §26.01(5).

Generally, grazing leases are classified either as a

“tenancy for a term of years” or a “periodic

tenancy.” A tenancy for term of years simply refers

to any set lease term (whether months or years) that

terminates upon the conclusion of the term. See

Thomas W. Merrill and Henry E. Smith, Optimal

Standardization in the Law of Property: The

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

9

Numerus Clausus Principle, 110 Yale L.J. 1, 11

(2000). Conversely, under a periodic tenancy, the

precise length of the lease is not included in the

lease itself, but is at the will of the landlord and

tenant. See Panola County Appraisal Review

Board v. Pepper, 936 S.W.2d 10, 12 (Texarkana

Ct. App. 1996). In this instance, the lease will

automatically renew at the end of the initial term

unless a specific notice of the intent not to renew is

given by either party. For leases containing

periodic tenancies, it is important to determine the

amount of notice that will be required. It is likely

in the best interest of both the landowner and tenant

to require a lengthy notice period so that in the even

the lease will not be renewed the landowner has

time to secure a new tenant and the lessee has time

to find alternative arrangements for his or her

livestock. It is advisable that notice be required to

be given in writing.

• Description of the land: The land need be

described so that both parties (and a judge or jury

if there ever were to be a dispute over the lease) can

understand exactly what land was being leased.

This can be done by legal metes-and-bounds

descriptions, a photograph or diagram showing the

specific location, or simply by words if a specific

description can be conveyed. Further, if there are

any areas that are to be excluded from the lease,

this limitation must be included in detail in the

lease agreement. For example, if there is an apple

orchard in the back corner of the property and the

landowner does not want the lessee’s cattle in that

area, this must be addressed in the lease.

• Stocking limitations: A grazing lease should set

forth stocking limitations that address the number

of head, breed, and species of animal permitted.

For example, the stocking rate may differ if the

lessee intends to run 1,000 pound Angus cattle on

the land versus if he or she intends to run 1,600

pound Charolais cattle on the land. Similarly, the

weight of stocker calves on the property may well

change the stocking limitations needed. A

landowner may want to address this issue and

specify the breed or size of cattle permitted.

Appendix V includes a chart from the Natural

Resource Conservation Service

1

is useful in

calculating animal units for various species.

• Price: The price for grazing leases varies based

upon a number of factors including the number of

acres of land, the available forage, the number of

livestock that may be grazed per acre, the type of

livestock to be grazed, etc. Price may be based

upon any formula that the parties desire, although

1

Chart developed by Steve Nelle and Stan Reinke, NRCS

with input from literature and other specialists from TCE

and TPWD.

most commonly, grazing leases are priced either

per acre, per head, or per animal unit. Additionally,

although less common in grazing leases than

farming leases, the parties could agree to a sort of

“crop share” lease based upon a percentage of the

calf crop sold. For more information on this topic,

refer to Section III above.

• Payment method: Payments may be made in any

manner agreed upon by the parties. Grazing leases

frequently require a pre-payment of at least some

portion of the lease, although some parties agree to

a monthly payment system. A landowner should

consider including details on exactly how and

when rent is due and including penalties and

interest for late payments.

• Failure to pay: In addition to imposing penalties

and interest on late payments, a landowner may

want to provide that once the total amount owed in

late payments, interest, and fees reaches a certain

amount, the landowner has the right to terminate

the lease. Further, landowners should be aware of

any statutory lien rights available to unpaid

landowners in their state, including understanding

any action that must be taken by the landowner for

such rights to be enforced. In Texas, the Texas

Agricultural Landlord’s Lien provides an

agricultural landlord a preference lien for rent that

becomes due and for the money and value of the

property that a landlord furnishes to a tenant to

grow a crop on the lease premises. See Texas

Property Code Section 54.001 - 54.007.

• Security deposit: A landowner may want to

consider requiring a security deposit to cover any

damage caused to the property, improvements,

fences, crops, or livestock while the lessee is in

possession of the property.

• Access to land: The lease should provide how the

lessee is to access the property, including

designating the points at which the lessee may enter

the property, any gates that the lessee may utilize,

and the roads on the property the lessee is permitted

to use.

• Use of vehicles or ATVs: The lease should state

whether the lessee is permitted to use vehicles or

ATVs on the property and, if so, whether there are

any areas where such vehicles are prohibited.

• Requirement gates be kept closed: A landowner

may wish to require that all gates be kept closed at

all times. Additionally, if other livestock is present

or in adjacent pastures, a landowner may also

include a requirement that the lessee is liable for

the death or injury of any livestock or damages to

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

10

a third party caused by any livestock that escape

due to a gate being left open by the lessee or his

employees.

• Use and repair of facilities on property: The

lease should discuss the right of the lessee to use

any facilities on the property including corrals,

buildings, barns, and houses. If any repairs are

necessary, the lease should describe who will be

responsible for undertaking repairs and paying for

both parts and labor. Common items of concern

during a grazing lease include fences, windmills,

and pumps.

• Inspection of fences: It is important that a lease

address who will be responsible to inspect and

repair fences, particularly where the leased

property abuts a highway. The lease should set

forth which party will make these inspections and

the frequency at which they should be made.

• Right to erect improvements on property: The

lease should address whether the lessee has the

right to erect any improvements on the property

during the lease. Generally, permanent

improvements will stay on the land after the

termination of the lease. Consequently, the

landowner may want to have an input on the

location and building specifications for any such

improvements. Some leases require the lessee to

obtain written permission from the landowner

before taking any such action. In order to avoid

confusion or conflict, the lease should specify

whether the lessee has the right to remove any

improvements at the end of the lease and set a

deadline for such removal.

• Landowner’s rights to the property: Unless

reserved, the landowner grants exclusive

possession of the property to the lessee, meaning

that the landowner may not enter the property. The

landowner may want to reserve the right to enter

the property for various reasons during the lease,

including to care for crops and to inspect the

premises. Importantly, a landowner should

discuss this issue with his or her attorney to

determine if the right to inspection might be

outweighed by liability concerns that such right

might impose. Further, if the landowner wants to

retain rights as to the property, including the right

to hunt, this should be expressly set forth in the

lease agreement.

• Other surface uses: There may be other surface

users of the property during the lease term.

Examples include oil and gas companies who may

have a mineral estate lease, hunters that may have

a hunting lease with the landowner, and the

landowner himself. The lease should expressly

identify all such surface users so the lessee is aware

of these uses and should require that the lessee will

act in good faith to accommodate and cooperate

with these other surface owners. With regard to a

potential mineral lessee, it is important to

understand that under Texas law, a mineral owner

is considered a dominant estate holder, meaning he

or she has the right to use as much of the surface

estate as is reasonably necessary to produce oil and

gas. See Plainsman Trading Co. v. Crews, 898

S.W.2d 786 (Tex. 1995). The same is true for a

severed groundwater owner. See Coyote Lake

Ranch v. City of Lubbock, 498 S.W.3d 53 (Tex.

2016). This may mean an oil rig showing up in the

or gathering lines being laid in the middle of a

leased pasture. A lessee may wish to include a

provision allowing the lessee to terminate the lease

in the event oil or gas production occurs on the

property. Additionally, alternative energy leases

such as solar or wind lease agreements are

becoming increasingly common in Texas. Parties

may need to address this issue in their lease

agreement and determine what will happen if the

surface owner wishes to enter into this type of

agreement during the term of the grazing lease.

• Care of livestock: Under some lease agreements,

a landlord may not only offer grazing land, but may

also agree to provide care for the livestock. In this

event, it is extremely important that the landowner

and lessee be specific with regard to their

expectations for care. For example, requiring

“adequate hay” is insufficient as it is almost a

certainty that the landlord’s definition of

“adequate” differs from the livestock owner’s

definition of the same term. In order to avoid this

type of dispute, a lease should spell out the

expectations of the landowner providing care of

livestock, including the type and amount of hay and

feed to be provided, the type of mineral that should

be available, the frequency with which the

livestock should be checked by the landowner, etc.

Finally, an interesting term found in some of these

types of leases provides an incentive for a

landowner who provides superior care for the

livestock. For example, the lease might provide

that if calves reach a certain average daily gain or

a set weaning weight goal, the landowner receives

a bonus from the lessee. Similarly, there could be

a provision if the landowner is set to care for first-

calf heifers that would include a bonus if there was

a low death loss percentage. This type of incentive

may help to ensure better care for livestock.

• Proof of vaccination: Some leases require that the

lessee provide the landowner with a health

certificate declaring that cattle have received

certain vaccinations, such as blackleg shots for

calves or Bang’s vaccinations for cows and bulls.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

11

• Breachy livestock: Many grazing leases involving

cattle include a provision whereby any animal

known to be “breachy” (i.e. frequently escaping the

pasture by jumping or breaking through fences),

must be removed from the premises.

• Disaster contingencies: The parties should

consider how disasters such as drought or fire may

impact the landlord/lessee relationship. In the

event that all or some of the grazing land is

destroyed, how will a determination regarding the

lease be made? Who will determine if it is

necessary to lower the number of livestock

permitted to be on the property, or whether it is

necessary to terminate the lease all together?

Parties may want to consider agreeing on a neutral

third party, such as a county extension agent, or

another livestock operator in the area, to help with

this determination. In the event that the lease is

limited or cancelled, the lease agreement should

address whether a refund of any pre-paid rent will

be made.

• Payment of property taxes. Parties should

address who will be responsible for paying

property taxes on the land during the lease term.

Commonly, a landowner will continue to pay

property taxes on the land. Parties should make

clear in the lease who is responsible for making the

required tax payment.

• Transferability: The lease should address the

rights of the parties as to assignment or sublease.

May the lessee sublease or assign his rights to a

third party without the landowner’s permission?

Under Texas statute, a sublease may not be entered

into without prior consent of the landlord. See

Texas Property Code Section 91.005. Including

this clause in a lease agreement ensures both parties

are aware of this requirement. Similarly, parties

should address what will happen to the lease if the

property changes ownership during the lease term.

The parties may want to provide a clause stating

that the lease shall be binding upon heirs or assigns,

or, conversely, that the lease shall terminate upon

the death of either of the parties.

• Lease does not create a partnership: Unless the

landowner and lessee intend to create a partnership,

the lease should expressly state that it does not do

so. This provision is important because generally,

one partner is liable for the obligations and debts of

the other partner. Although this type of provision,

alone, will not prevent a partnership from being

created in all circumstances, it does provide

evidence that the parties did not intend to create a

partnership arrangement. See, e.g., Ingram v.

Deere, 488 S.W.3d 886 (Tex. 2009).

• Effect of breach: Many leases include a clause

stating that the violation of any term, covenant, or

condition of the lease agreement by the lessee

allows for the landowner, at his option, to terminate

the lease upon notice to the lessee. This provision

allows the landowner the option of terminating the

lease of any term is violated, rather than merely

having the right to sue the lessee for damages. If

included, this clause should address the type of

notice required to the lessee and whether any

refund of payment or security deposit will be

available.

• Damages to property: The lease should prohibit

damage to the property and require the lessee to

repair or pay for any damage caused including the

destruction of crops, death or injury to livestock,

harm to fences, gates or improvements, and trash

or other debris left on the premises.

• Liquidated damages: A lease may provide for

certain liquidated damages, which essentially mean

contractually agreed upon damage amounts. These

damages are often used in situations where the

calculation of actual damages might be difficult.

Instead, the parties agree up front to a set amount

of damages for certain actions.

• Attorney’s Fees: Generally, a successful litigant

is not entitled to recover his or her attorney fees

from the other party absent a contractual agreement

or a statute so authorizing. A landowner should

consider including a provision providing that if the

landowner is successful in a dispute (whether in

arbitration or in court) with the lessee, the lessee

will be responsible for the landowner’s reasonable

costs and attorney’s fees. The lessee will likely

request a reciprocal clause requiring payment of his

or her attorney fees if the lessee is successful.

• Lessee Insurance: A landowner may require the

lessee to acquire liability insurance that will be

maintained throughout the lease term. If so, the

landowner should also require that the lessee

include the landowner as an “additional insured.”

This should offer insurance coverage to the

landowner pursuant to the lessee’s policy in the

event of a claim made by a third party against the

lessee and landowner. The landowner may also

want to require a specific minimum level of

coverage.

• Liability and Indemnification: A landowner

should consider including liability and

indemnification clauses in case the landowner is

sued as a result of the lessee’s conduct. These

terms simply provide that the landowner is not

liable for any action or inaction of the lessee, his

agents, or employees and that, in the event the

landowner is sued for the lessee’s actions or

inactions, the lessee will hold the landowner

harmless as to any attorney’s fees or judgment.

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

12

• Choice of law: A choice of law provision in a lease

allows the parties to determine which state’s law

will govern the lease in the event of a dispute.

Generally, choice of law clauses are enforced by a

court so long as they are not against public policy

and are reasonably related to the contract. Because

many laws vary by state and a choice of law

provision could significantly impact rights under a

lease, a landowner should consult with an attorney

with regard to this provision to determine the

potential options available and to determine which

would be most advantageous to the landowner.

• Forum clause: A forum clause provides that a

dispute over a lease will be heard in a particular

location or court. For example, a lease could

require that any dispute over the lease be filed in

the county where the land is located. This clause

may be important for a landowner by requiring suit

to be filed in his or her county, particularly if the

lessee lives some distance away.

• Dispute resolution: A landowner should consider

the inclusion of a dispute resolution clause. The

purpose of these types of clauses is to limit the time

and expenses of a court action in the event of a

dispute. There are two primary types of dispute

resolution: arbitration and mediation. In

arbitration, a third-party arbitrator (usually an

attorney) will hear evidence and render a decision.

If the arbitration is “binding” that judgment is final

on the parties absent evidence of fraud by the

arbitrator. Mediation, on the other hand, involves

a neutral third party who will work with the

landowner and lessee to attempt to reach a

mutually-acceptable resolution. If both parties

refuse to agree to settle, the case will then proceed

on to court. A dispute resolution clause should

identify how the arbitrator or mediator will be

selected. It is important to understand the

difference between these options and determine

which option is best in consultation with an

attorney.

• Confidentiality clause: The landowner may want

to consider the use of a confidentiality clause if

there is any information that he or she does not

want made public. For example, a landowner may

not want the fee charged to one party disclosed if

the landowner intends to charge an increased fee to

another party or in the future.

There are numerous sample forms available online for

grazing leases. A list of several form leases available

for free are included in Appendix VI.

V. FARM LEASE CHECKLIST

Just as was the case with the grazing lease

checklist, the following checklist includes many of the

most common terms found in farm lease agreements, but

the list is neither exhaustive, nor will every term be

needed in every lease agreement.

• Names of the parties: The lease should include

the name and address of the parties, both the

landowner and the lessee.

• Duration of lease: The length of the lease should

be specified with particularity and may range from

a matter of months to several years. It is important

to note that leases of certain durations may be

required to be in writing in order to be enforceable.

For example, pursuant to the Statute of Frauds,

Texas requires a lease of real property lasting for

more than 1 year to be in writing. See Texas

Business & Commerce Code §26.01(5).

Generally, farm leases are classified either as a

“tenancy for a term of years” or a “periodic

tenancy.” A tenancy for term of years simply refers

to any set lease term (whether months or years) that

terminates upon the conclusion of the term. See

Thomas W. Merrill and Henry E. Smith, Optimal

Standardization in the Law of Property: The

Numerus Clausus Principle, 110 Yale L.J. 1, 11

(2000). Conversely, under a periodic tenancy, the

precise length of the lease is not included in the

lease itself, but is at the will of the landlord and

tenant. See Panola County Appraisal Review

Board v. Pepper, 936 S.W.2d 10, 12 (Texarkana

Ct. App. 1996). In this instance, the lease will

automatically renew at the end of the initial term

unless a specific notice of the intent not to renew is

given by either party. For leases containing

periodic tenancies, it is important to determine the

amount of notice that will be required. It is

advisable that notice be required to be given in

writing.

• Right to harvest after lease terminates: There

are a number of reported Texas cases addressing

right to fa tenant where crops were planted and

grown during the term of the lase, but which have

not been harvested and removed by the time the

agreement terminates. The common law “doctrine

of emblements” provides relief for a tenant under

narrow circumstances. See Dinwiddie v. Jordan,

228 S.W. 126 (Tex. Ct. App. 1921). In order to

succeed in gaining access to the property to harvest

growing crops, a tenant must prove: (1) the lease

was for an uncertain duration; (2) termination of

lease was due to an act of God for the landlord, but

was not the fault of the tenant; and (3) the crop was

planted during the right of occupancy. See id.

Rather than relying on this narrowly constructed

Farm and Ranch Leases Chapter 6

13

common law doctrine, parties should address this

issue in their lease agreements.

• Description of the land: The land need be