Statistical Commission Background document

Fifty-fourth session Available in English only

28 February – 3 March 2023

Item 4(e) of the provisional agenda

Items for decision: Refugee, internally-displaced persons and stateless statistics

International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics

(IROSS)

Prepared by the Expert Group on Refugee, Internally Displaced Persons and

Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS)

International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics (IROSS)

DRAFT 7.0

FOR SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS STATISTICAL COMMISSION

20 January 2023

1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics (IROSS) were developed by the Expert

Group on Refugee, Internally Displaced Persons and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS). The

recommendations were developed in close collaboration between experts from governments and regional

and international organisations, as well as subject-matter experts.

From country level, the following contributed to development of the IROSS: Sok Kosal (National Institute

of Statistics, Cambodia); Camilo Andres Mendez Coronado (National Administrative Department of

Statistics, DANE, Colombia); Kô Fié Didier Laurent Kra (National Institute of Statistics, Cote d’Ivoire);

Lamiaa Mohsen Mohamed Elgebaly (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, Egypt);

Phumlile Dlamini (Central Statistical Office Eswatini); Renice Akinyi Bunde and Robert C. Buluma

(Kenya National Bureau of Statistics); Osmonkulova Aigerim (Social Statistics Division of Bishkek City

Statistical Office); Zhyldyz Sherimbekova (National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyzstan); Noor Faadlilah

Ismail (Department of Statistics, Malaysia); Alejandra Ríos (National Institute of Statistics and Geography,

Mexico); Helge Brunborg (Statistics Norway); Sohail Jehangir and Saqib Jamal (National Database and

Registration Authority (NADRA), Pakistan); Haleema Saeed, Hana Al Bukhari, Mohammed Duraidi and

Dyala Ibrahim (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics); Henedin Palabras, Edithia Orcilla and Marizza

Grande (Philippine Statistics Authority); Venant Habarugira (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda);

Munasinghe Liyana Arachchige Pushparani Gunaskara and Prajeewa Hettiyani (Department of Census and

Statistics, Sri Lanka); Thitiwat Kaew-Amdee and Chirawat Poonsab (National Statistical Office, Thailand);

Olena Shevtsova (State Statistics Service of Ukraine); Eric Jensen and Nobuko Mizoguchi (US Census

Bureau); Nicole Shepardson and Seth Perlman (US State Department); Alisher Rakhimov and Sanjarbek

Melikhujaev (State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics); Tran Cam An and Tran Khanh

(General Statistics Office, Vietnam); and Langton Chikeya, Rachael Rester Tsuarai and Timothy Mumba

(Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency).

From regional and international organisations, the following took part in the work: Samson Bel-Aube

Nougbodohoue (African Union); Giampaolo Lanzieri and Silvia Andueza Robustillo (Eurostat); Giulia

Tshilumba (International Organization for Migration (IOM)); Afsaneh Yazdani, Petra Nahmias and Tanja

Sejersen (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP));

Léandre Foster Ngogang Wandji (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UN ECA)); Marwan

Khawaja (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN ESCWA)); Romesh

Silva and Renee Sorchi (United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)); Aina Helen Saetre, Anne Laakko,

Bongkot Napaumporn, Fernando Bissacot, Gert Bruininkx, Hyunju Park, Monika Sandvik, Olivia Gaceri

Mugambi, Radha Govil, Sadiq Kwesi Boateng, Sebastian Steinmuller, and Tarek Abou Chabake (United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)); Jan Beise (United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF)); Vitoria Cetorelli (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near

East (UNRWA)); Vibeke Oestreich Nielsen (UN Statistics Division (UNSD)); Emi Suzuki (World Bank

(WB)); and Felix Schmieding (WB-UNHCR Joint Data Center (JDC)).

The work was coordinated by the Secretariat of the EGRISS, with special thanks to Mary Strode, Natalia

Krysnky Baal, Charis Oluwamayowa Sijuwade, Carolina Ferrari, Ronan Pros, Filip Mitrovic and Fabiana

Pineda Sosa. Financial contributions that made this work possible were generously made available by

UNHCR and WB-UNHCR Joint Data Center.

2

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................... 1

Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................ 6

Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 8

A. NEED FOR RECOMMENDATIONS ON STATELESSNESS STATISTICS ................................................. 8

B. PROCESS OF DEVELOPING THE RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................. 10

C. COMPLEMENTING EXISTING STATISTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................ 12

D. STRUCTURE OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................... 12

Chapter 2: Legal Framework and Definition of a Stateless Person ............................................... 14

A. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON STATELESSNESS AND THE RIGHT TO A NATIONALITY14

1. International Legal Framework ............................................................................................................... 14

2. UNHCR’s Mandate on Statelessness ...................................................................................................... 15

B. DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................. 16

1. Stateless Person ....................................................................................................................................... 16

2. Person of Undetermined Nationality ....................................................................................................... 17

3. Potentially Associated but Distinct Groups ............................................................................................. 18

C. CONTRIBUTORY CAUSES OF STATELESSNESS .............................................................................. 19

D. IMPACT OF STATELESSNESS ON IMPACTED POPULATIONS .......................................................... 21

E. SOLUTIONS TO STATELESSNESS ................................................................................................... 21

F. STATELESSNESS STATUS DETERMINATION .................................................................................. 22

G. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................ 23

Chapter 3: Statistical Definitions of Stateless Populations ............................................................. 24

A. THE STATELESSNESS STATISTICAL FRAMEWORK ....................................................................... 24

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 24

2. Population Categories Included in the Statelessness Statistical Framework ........................................... 24

3. Defining Population Categories in the Statelessness Statistical Framework ........................................... 26

4. Impacted Populations not Included in the Statelessness Statistical Framework ..................................... 29

B. ALIGNMENT TO OTHER STATISTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCEPTS ............................... 30

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 30

2. Citizenship, Nationality, and Statelessness ............................................................................................. 30

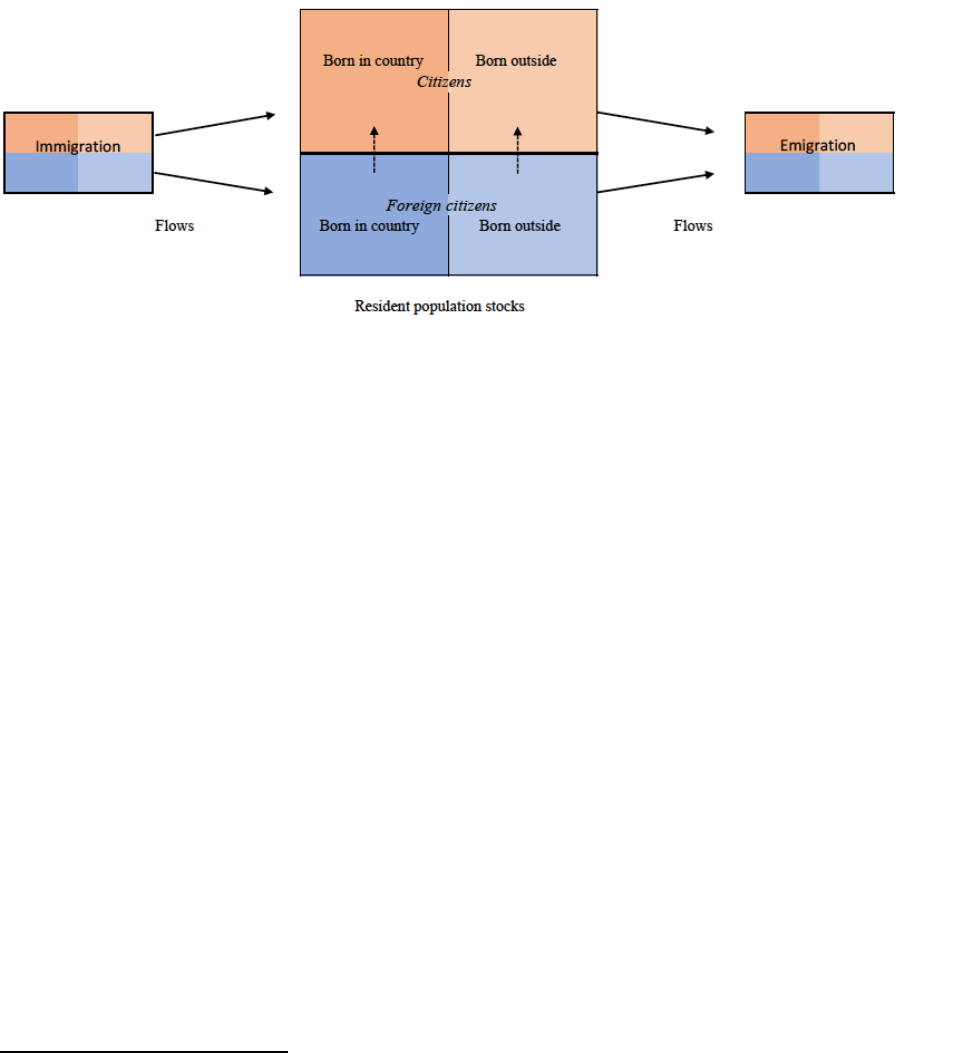

3. Stateless Persons as Part of the Resident Population of a Country ......................................................... 33

4. Statelessness and International Migration ............................................................................................... 34

5. Statelessness and Migratory Causes of Statelessness .............................................................................. 36

6. Statelessness and Forced Displacement .................................................................................................. 36

C. STOCKS AND FLOWS OF STATELESS POPULATIONS ..................................................................... 38

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 38

2. Definitions of Stocks and Flows in the Demographic Context ............................................................... 38

3. Stocks Within the Statelessness Statistical Framework .......................................................................... 38

4. Flows Into, Out of and Within the Statelessness Statistical Framework ................................................. 39

D. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................. 41

Chapter 4: Statistics on Statelessness for Countries to Produce .................................................... 42

A. BASIC CLASSIFICATORY VARIABLES ........................................................................................... 42

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 42

2. Basic Classificatory Variables ................................................................................................................ 42

3. Linking Basic Classificatory Variables to the Populations Categories in the Statelessness Statistical

Framework .................................................................................................................................................. 44

4. Linking Basic Classificatory Variables to the Different Contributory Causes of Statelessness .............. 46

3

B. STATISTICS RELATING TO STOCKS AND FLOWS .......................................................................... 48

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 48

2. Stock Statistics ........................................................................................................................................ 48

3. Flow Statistics ......................................................................................................................................... 49

C. BASIC STATISTICS RELATING TO MEASURING CHARACTERISTICS OF STATELESS POPULATIONS52

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 52

2. Recommendations on Socio-demographic Analysis and Indicators of Statelessness ............................. 52

3. The SDGs and Priority Indicators for Statelessness ................................................................................ 56

4. Important Considerations for Analysis of Statelessness Data ................................................................. 59

D. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................. 60

Chapter 5: Data Sources and Data Integration ................................................................................ 61

A. POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUSES ....................................................................................... 61

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 61

2. Description of Data Source ..................................................................................................................... 61

3. Using a National Census for Measuring the Number and Characteristics of Stateless Persons .............. 62

4. Existing International Recommendations on National Census ............................................................... 63

5. Specific Recommendations on Modifying the Census Questionnaire to Collect Statelessness Data ...... 65

6. Specific Recommendations on Ensuring Appropriate Coverage of Stateless Populations in Censuses .. 66

7. Quality Considerations and Data Protection ........................................................................................... 68

B. SAMPLE SURVEYS ........................................................................................................................ 70

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 70

2. Description of Data Source ..................................................................................................................... 70

3. Using Sample Surveys for Measuring the Number and Characteristics of Stateless Persons ................. 71

4. Existing International Recommendations on this Data Source ............................................................... 74

5. Specific Recommendations on Modifying the Instrument/Questionnaire ............................................... 74

6. Specific Recommendations on Ensuring Appropriate Coverage of Stateless ........................................ 75

7. Quality Considerations and Data Protection .......................................................................................... 76

C. ADMINISTRATIVE DATA ............................................................................................................... 77

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 77

2. Description of Data Source ..................................................................................................................... 77

3. Using Administrative Data for Measuring the Number and Characteristics of Stateless Persons .......... 81

4. Existing International Recommendations on Administrative Data Sources ............................................ 84

5. Specific Recommendations on Modifying Forms/Instruments .............................................................. 85

6. Specific Recommendations on Ensuring Appropriate Coverage of Stateless Persons ............................ 86

7. Quality Considerations and Data Protection ........................................................................................... 88

D. DATA SOURCES DEVELOPED BY NON-GOVERNMENT ACTORS ................................................... 90

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 90

2. Defining Data Sources Developed by Non-Government Actors ............................................................. 90

3. Citizen-Generated Data ........................................................................................................................... 92

4. Using CGD Sources for Official Statistics .............................................................................................. 93

5. Quality Considerations ............................................................................................................................ 94

E. DATA INTEGRATION ..................................................................................................................... 95

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 95

2. Data Integration ....................................................................................................................................... 95

F. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................ 98

Chapter 6: Statistical Coordination and the Data Ecosystem ...................................................... 100

A. WHAT IS COORDINATION AND WHY IT IS NEEDED? .................................................................. 100

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 100

2. What is Statistical Coordination? .......................................................................................................... 100

3. Why is Statistical Coordination Important and What are the Prerequisites? ......................................... 101

B. COORDINATION AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL ................................................................................ 102

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 102

4

2. Existing Challenges in National Statistical Coordination on Statelessness ........................................... 102

3. Recommendations to Improve Statistical Coordination at the National Level ..................................... 103

C. COORDINATION AT THE REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEVELS ........................................... 107

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 107

2. Challenges Concerning Statistical Coordination at the Regional and International Levels .................. 107

3. Recommendations to Improve Statistical Coordination at the Regional and International Levels ....... 108

D. CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT ......................................................................................................... 114

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 114

2. Capacity Development Conceptual Framework .................................................................................... 114

3. Capacity Development Recommendations ........................................................................................... 115

F. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................... 118

References .......................................................................................................................................... 119

5

BOXES, FIGURES AND TABLES

Box 3.1 Citizenship and Nationality………………………………..……………………………32

Box 3.2 Place and Country of Usual Residence…………………………………………………34

Box 4.1 OSCE Handbook on Statelessness……………………………………………………...53

Box 4.2 SDG Goals, Targets and Indicators of Particular Relevance to Statelessness………….57

Box 4.3 Priority SDG Indicators for Displaced Populations……………………………………...58

Box 6.1 High-level Segment on Statelessness………...………………………………………...113

Figure 3.1 The Statelessness Statistical Framework……………………………………………..25

Figure 3.2 Conceptual Framework on International Migration and Coherence Between Flows and

Stocks…………………………………………………………………………………………….35

Figure 3.3 Statelessness in the International Migration Framework…………………………….36

Figure 3.4 Overlapping Population Groups: Stateless Persons, Refugees and IDPs…………….37

Figure 3.5 Flow Model for Stateless Persons and Those Without a Recognised Nationality

Status……………………………………………………………………………………………..39

Figure 3.6 Flows Model from Persons Without a Recognised Nationality Status (Category C) to

Persons With a Recognised Stateless Status (Category B)………………………………………40

Figure 6.1 The Various Levels of the Data Ecosystem………………………………………...115

Table 2.1 Contributory Causes of Statelessness………………………………………………….20

Table 3.1 The Statelessness Statistical Framework………………………………………………26

Table 4.1 Variables Required to Classify People in the Statelessness Statistical Framework……45

Table 4.2 Selecting Basic Classificatory Variables Based on Different Contributory Causes of

Statelessness……………………………………………………………………………………...47

Table 5.1 IROSS Recommended Variables for Analysis of Characteristics of Stateless Persons

Included in the UN P&R as Recommended Topics……………………………………………64

Table 5.2 IROSS Recommended Variables for Analysis of Characteristics of Stateless Persons

Included in the Major Population and Household Surveys………………………………………73

Table 5.3 IROSS Recommended Variables for Analysis of Characteristics of Stateless Persons

using Administrative Data Sources……………………………………………………83

6

ABBREVIATIONS

ACS

American Community Survey

ASEAN

AU

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

African Union

CCSA

CD4.0

Committee for the Coordination of Statistical Activities

Capacity Development 4.0 Framework

CGD

Citizen-Generated Data

CRVS

DESA

Civil Registration and Vital Statistics

Department of Economic and Social Affairs

DHS

ECOSOC

ECOWAS

Demographic Household Survey

Economic and Social Council

Economic Community of West African States

EGRIS

EGRISS

EICV

Expert Group on Refugee and Internally Displaced Persons Statistics

Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics

Enquête Intégrale sur les Conditions de Vie des ménages

EU

European Union

FDP

GA

HBS

HIES

HMIS

HLS

IAEG-SDGs

ICCPR

ICT

ID

IT

Forcibly Displaced Person

General Assembly

Household Budget Survey

Household Income and Expenditure Survey

Health Management Information System

High-Level Segment

Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Information and Communication Technology

Identification Card

Information Technology

IDP

Internally Displaced Person

IOM

International Organisation for Migration

IRIS

International Recommendations on IDP Statistics

IRRS

IROSS

ISIC

JDC

International Recommendations on Refugee Statistics

International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics

International Standard Industrial Classification

Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement

JIPS

Joint IDP Profiling Service

LFS

Labour Force Survey

LSMS

Living Standards Measurement Survey

MICS

MRP

NADRA

Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey

Multilevel Regression with Poststratification

National Database and Registration Authority

NGO

Non-Governmental Organisation

NQAF

National Quality Assessment Framework

NSDS

National Strategy for the Development of Statistics

NSO

NSS

National Statistical Office

National Statistical System

OECD

OSCE

PARIS21

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe

The Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21

st

Century

7

RDS

Respondent Driven Sampling

SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

SDP

SILC

UN

UNECA

Statelessness Determination Procedure

Statistics on Income and Living Conditions Survey

United Nations

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

UNECE

UNFPA

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

United Nations Population Fund

UNESCAP

UNESCWA

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

UNHCR

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF

UN LIA

UN P&R

UNRWA

UNSC

United Nations Children’s Fund

United Nations Legal Identity Agenda

United Nations Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing

Censuses

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

United Nations Statistical Commission

UNSD

VNR

WASH

WB

United Nations Statistics Division

Voluntary National Review

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

World Bank

8

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1. The International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics (IROSS) present a

comprehensive set of recommendations for how countries should produce statistics on

statelessness. This includes a statistical framework and guidance on how this should be

operationalised in specific national contexts, including through the use of different data sources

and practical guidance to strengthen statistical coordination.

2. The introductory chapter aims to contextualise this effort and introduce the rationale of the

development of these recommendations. It outlines key challenges regarding the production of

statelessness statistics, describes how the recommendations were developed, highlights key

linkages to other international statistical guidelines and presents a summary of the structure of the

recommendations that follow to help guide readers.

A. NEED FOR RECOMMENDATIONS ON STATELESSNESS STATISTICS

3. A stateless person is someone “who is not considered a national by any state under the

operation of its law”.

1

Where a person lacks any nationality, he or she cannot enjoy the rights and

protections offered to citizens, limiting their access to healthcare, education, formal employment,

participation in elections and travel. This legal definition provides the basis for the statistical

definition of stateless persons used throughout the recommendations (see Chapters 2 and 3 for

more details). The nature of the definition itself speaks to the current challenges in existing official

statistics on statelessness.

4. Currently, the global estimated number of stateless persons sits at 4.3 million.

2

However,

this figure underestimates the number of stateless persons due to its reliance on incomplete national

data.

3

The definitions, concepts and classifications employed to measure statelessness statistics

reflect country-specific legislation, policies and practices and therefore are not globally

harmonised. The variation in the methods of data collection, compilation and presentation at

national levels further limits the comparability of statelessness statistics internationally.

Additionally, the lack of recognition of stateless persons and subsequent under-reporting of this

group further contributes to the statelessness data gap. Consequently, statistics produced by

different countries differ tremendously in availability, quality and accuracy.

5. Data concerning stateless populations are often collected through administrative systems,

which contain data on stateless persons as a result of their interactions with national authorities.

However, the lack of legal status and societal marginalisation experienced by stateless populations

1

UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, 28 September 1954, United Nations, Treaty

Series, vol. 360, p. 117 (available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3840.html).

2

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR Global Trends 2021: Forced Displaced in 2021, June 2022

(available at: https://www.unhcr.org/62a9d1494/global-trends-report-2021). UNHCR compiles figures on statelessness to include

both stateless persons and persons with “undetermined nationality”.

3

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR Statistical Reporting on Statelessness, October 2019 (available at:

https://www.unhcr.org/en-in/statistics/unhcrstats/5d9e182e7/unhcr-statistical-reporting-statelessness.html).

9

often discourage them from declaring themselves to government authorities or even identifying

themselves as stateless in anonymous data collection processes. In addition, some stateless persons

may not recognise themselves as such. Collectively, these factors create challenges for including

these populations in related data collection exercises. It is therefore anticipated that there are large

numbers of stateless or similar groups that remain statistically, or otherwise, undetected.

6. These factors may prevent national authorities from accurately estimating the number of

stateless persons and understanding their basic and ongoing needs. Insufficient data prevents

comparisons with other vulnerable groups and the monitoring of adherence to international

commitments. It also hinders the development of evidence-based policies that are necessary to

improve the living conditions of stateless persons and others impacted by statelessness.

7. Several international commitments, such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

(Agenda 2030) and its commitment to leave no one behind

4

and the United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Global Action Plan to End Statelessness (particularly

Action 10: Improve Quantitative and Qualitative Data on Stateless Populations),

5

and the UN

Legal Identity Agenda (UN LIA)

6

call for improved statelessness statistics; either as a means to

ensure the visibility of vulnerable populations within the broader development agenda, or, more

specifically, to better understand the causes and impacts of statelessness as a means to identify

national durable solutions. These calls are further supplemented by a growing interest among

States to collect more and better data on statelessness as highlighted during the 2019 High Level

Segment on Statelessness.

7

8. Despite these persistent statistical challenges on the one hand and numerous national and

international commitments to improve data on the other, no comprehensive set of international

recommendations on statelessness statistics is available. Although statelessness is a consideration

in existing statistical recommendations – e.g., Principles and Recommendations for Population

and Housing Censuses (UN P&R),

8

Principles and Recommendations for a Vital Statistics System

9

and UNHCR Reporting Definitions

10

– it is not comprehensively addressed. For example, the UN

P&R define stateless populations and provide guidance on how to capture stateless persons in

census. However, the recommendations provide inadequate guidance on how to distinguish

between those recognised as stateless by national authorities and those that are not, which is

important when trying to accurately capture the entirety of stateless populations in national

statistics.

4

United Nations, Leaving No One Behind: Equality and Non-Discrimination at the Heart of Sustainable Development, 2017,

New York (available at: https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/imported_files/CEB%20equality%20framework-A4-web-rev3.pdf).

5

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Global Action Plan to End Statelessness 2014-2024 (available at:

https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/53823).

6

See the UN Legal Identity Agenda (available at: https://unstats.un.org/legal-identity-agenda/).

7

Pledges were submitted by States during the High-level Segment on Statelessness, which took place in Geneva on 7 October

2019(full list of pledges is available at: https://www.unhcr.org/ibelong/results-of-the-high-level-segment-on-statelessness/).

8

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) – Statistics Division, UN Principles and Recommendations for

Population and Housing Censuses (UN P&R), 2017, Revision 3 (available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-

social/Standards-and-Methods/files/Principles_and_Recommendations/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Series_M67rev3-

E.pdf).

9

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) – Statistics Division, Principles and Recommendations for a Vital

Statistics System, 2014, Revision 3 (available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/standmeth/principles/m19rev3en.pdf).

10

See UNHCR Reporting Definitions (available at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/methodology/definition/).

10

9. Therefore, the need to develop the IROSS was identified. These recommendations provide

guidance for national statistical authorities and their partners on the production and dissemination

of statistics on statelessness to improve the quality of these statistics at national level and, in turn,

strengthen globally consolidated data. In this way, the IROSS aim to facilitate the improvement of

national responses to statelessness by providing stronger evidence to support the development of

policies that identify durable solutions and aim to improve the lives and well-being of stateless

persons. It also aims to enhance global policy development and the support of the international

community to national responses, informed by more reliable and more easily comparable data and

statistics on statelessness and impacted populations.

B. PROCESS OF DEVELOPING THE RECOMMENDATIONS

10. During the fifty-first session of the Statistical Commission in 2020, several delegations

acknowledged the need to develop standards on statelessness statistics and expressed their support

for the proposal presented by Kenya to further develop the IROSS. This work built upon previous

efforts initiated in 2019 by a group of subject-matter experts and affected countries who worked

on an initial draft set of recommendations in 2020-2021.

11

11. At the fifty-second Statistical Commission in 2021, the side event “Leaving No One

Behind: Improving Statistics on Statelessness” was aimed at informing the statistical community

about the current scarcity and weaknesses of official statistics needed to estimate the size and

characteristics of stateless populations globally. In November 2021, following a thorough review

process, the Bureau of the Commission agreed to update the terms of reference of the Expert Group

to adjust its name to the Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS)

12

and include work on statelessness statistics and the development of international

recommendations.

12. During the fifty-third Statistical Commission in 2022, the EGRISS submitted the technical

Report of the Expert Group on Refugee, Internally Displaced Persons and Statelessness Statistics

on Statelessness Statistics

13

for discussion. The Statistical Commission “welcomed the report …

and approved the overall structure of the draft IROSS”.

14

In addition, the Statistical Commission

highlighted areas for improvement and provided guidance on how to finalise the recommendations.

More specifically, the Statistical Commission encouraged the Expert Group to develop guidance

on the integration of different data sources, requested that the recommendations enable the

11

Experts met in Ankara (February 2019) and subsequently in Bangkok (December 2019) to discuss the need for developing and

adopting common standards and definitions to improve the quality and quantity of statistics about stateless populations.

Participants at the Bangkok meeting included experts from national statistical offices and line ministries, with 16 countries

represented from Asia, Africa and Europe (Cambodia, Côte d’Ivoire, Eswatini, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Pakistan,

Philippines, Rwanda, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vietnam and Zimbabwe) alongside staff from

eight United Nations and international organisations.

12

The Expert Group on Refugee and IDP Statistics (EGRIS) was established by a decision of the 47th session of the UNSC in

2016. (The Group’s Terms of Reference are available at: https://egrisstats.org/about/terms-of-reference/).

13

The Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS), Report of the Expert Group on Refugee, Internally

Displaced Persons and Statelessness Statistics on Statelessness Statistics, December 2021 (available at:

https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/53rd-session/documents/2022-10-StatelessnessStats-E.pdf).

14

United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC), Implementation of the United Nations Legal Identity Agenda: Civil

Registration and Vital Statistics, March 2022, Item 3f (available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/53rd-

session/documents/2022-41-FinalReport-E.pdf).

11

measurement of stateless population characteristics and called on the Expert Group to provide

strong guidance on data quality, coordination and statistical capacity building for harmonised

reporting on statelessness statistics.

13. Guidance received from the Statistical Commission concerning the operationalisation of

the framework was addressed during a meeting in June 2022 with the EGRISS statelessness

subgroup members.

15

The subgroup meeting facilitated a collaborative environment where

subgroup members revised the statelessness statistical framework to ensure relevant populations

were adequately included, developed operational guidance on statelessness data collection using

traditional data sources and data sources produced by non-government actors, and proposed a

methodology to statistically capture the characteristics of stateless populations. Additionally, in

response to guidance received from the Statistical Commission, the group developed

recommendations to improve statistical coordination and increase statistical capacity at the

regional, national and international levels.

16

14. The UN Statistics Division (UNSD) facilitated a global consultation of the draft

recommendations in October-November 2022. The purpose of the global consultation was to

obtain the views of a wider group of stakeholders, including national statistical offices, civil

society, and regional and international bodies on the coherence, scope, coverage and applicability

of the recommendations. Through the global consultation a total of 38 feedback submissions were

received, including input from 31 countries.

17

Overall, the feedback received was positive,

welcoming the initiative to develop the recommendations and reflecting on opportunities to

improve data on statelessness at the national level. Concrete suggestions on how to further

strengthen the recommendations were also provided and have been addressed directly in the final

draft and/or as appropriate.

18

The completed draft of the IROSS therefore benefitted from the

collaborative effort of the EGRISS members and other contributors through the global

consultation; they are hereby submitted to the fifty-fourth Statistical Commission in 2023.

15

The EGRISS membership currently comprises 55 countries and 34 international and regional organisations, with work ongoing

to identify further participants. The EGRISS subgroup on statelessness worked collaboratively to address the guidance received

from the Statistical Commission. The EGRISS Statelessness subgroup comprises the following: Cambodia, Colombia, Cote

d’Ivoire, Egypt, Eswatini, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Norway, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Rwanda, Sri Lanka,

Thailand, Ukraine, US, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Zimbabwe, African Union, Eurostat, IOM, JDC, UN ECA, UN ESCAP, UN

ESCWA, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNRWA, UN Statistics Division, and World Bank.

16

The Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS), EGRISS Statelessness Subgroup Meeting to

Finalize the International Recommendations on Statelessness Statistics (IROSS): Meeting Report, July 2022 (available at:

https://egrisstats.org/resource/iross-meeting-report/).

17

Feedback was received from the Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia; State Statistical Committee, Azerbaijan;

National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus; Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina; Statistics Canada;

National Institute of Statistics and Census of Costa Rica; Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Human Mobility, Ecuador; Federal

Statistical Office, Germany; Hungarian Central Statistical Office; Central Statistics Office, Ireland; Statistical Coordination

Department, Israel; Italian National Institute of Statistics; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; Central Statistical Bureau of

Latvia; Statistics Lithuania; National Institute of Statistics and Geography, Mexico; Statistics Netherlands; National Institute of

Statistics and Informatics, Peru; Statistics Poland; Statistics Portugal; Planning and Statistics Authority, Qatar; Statistical Office

of the Republic of Serbia; Singapore Department of Statistics; Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic; Statistical Office of the

Republic of Slovenia; National Statistics Institute, Spain; Statistics Sweden; Swiss Federal Statistical Office; Department for

Planning, Development and International Cooperation State Statistics Service of Ukraine; United States Census Bureau; General

Statistics Office of Viet Nam; Civil Society Organisations; UNFPA; UNHCR; UNSD and the World Bank.

18

All the comments received during the Global Consultation have been addressed and responses documented (available upon

request).

12

C. COMPLEMENTING EXISTING STATISTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

15. The IROSS build on and complement the International Recommendations on Refugee

Statistics (IRRS)

19

and the International Recommendations on Internally Displaced Persons

Statistics (IRIS),

20

presenting the third set of international statistical recommendations produced

by the EGRISS.

21

They also follow a similar structure to the IRRS and IRIS. The linkages between

these documents (identified in relevant places through the subsequent chapters) are important as,

collectively, they present a comprehensive approach to improve the quality of official statistics

produced by national statistical systems on refugees, internally displaced and stateless persons –

including consideration of existing overlaps between the relevant population categories (e.g.,

stateless persons who can also be displaced within/across borders).

16. The IROSS aim to situate statelessness statistics within the wider body of statistical

recommendations and processes by aligning itself with the Recommendations on Statistics of

International Migration,

22

the UN P&R, the Principles and Recommendations for a Vital Statistics

System, the work of the UN Legal Identity Agenda Task Force,

23

and other relevant statistical

recommendations and processes that have been endorsed/supported by the Statistical Commission

(see Chapters 3 and 5 in particular). The IROSS build on these previously endorsed

recommendations by offering a more comprehensive set of guidelines on how national statistical

systems can better produce official statistics on statelessness.

D. STRUCTURE OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS

17. The IROSS present a comprehensive statelessness statistical framework and provide

recommendations to support national statistical systems, and other relevant stakeholders, in efforts

to improve official statistics.

18. The remaining chapters of the recommendations are structured as follows:

• Chapter 2: Legal Framework and the Definition of Stateless Persons summarises

the legal context and presents the legal definition of stateless persons. The chapter

discusses how the definitions can vary and reflects on related legal challenges.

• Chapter 3: Statelessness Statistical Framework presents the statistical definitions of

the various population categories within the framework and outlines the stocks and

flows of stateless populations.

19

Expert Group on Refugee, IDP, and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS), International Recommendations on Refugee Statistics

(IRRS), March 2018 (available at: https://egrisstats.org/recommendations/international-recommendations-on-refugee-statistics-

irrs/).

20

Expert Group on Refugee, IDP, and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS), International Recommendations on Internally Displaced

Persons Statistics (IRIS), March 2020 (available at: https://egrisstats.org/recommendations/international-recommendations-on-

idp-statistics-iris/).

21

The Expert Group on Refugee, IDP and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS), Compilers’ Manual on Displacement Statistics,

February 2020. Once the IROSS is finalised and endorsed this manual will be updated to also address and incorporate

statelessness (available at: https://egrisstats.org/wp-content/uploads/BG-item-3n-compilers-manual-E.pdf).

22

United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Recommendations on Statistics of

International Migration, Revision 1, United Nations, New York, 1998 (available at:

https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_58rev1e.pdf).

23

The UN Legal Identity Task Force (available at: https://unstats.un.org/legal-identity-agenda/).

13

• Chapter 4: Statistics on Statelessness for Countries to Produce outlines the basic

statistics that are recommended to produce stocks and flows and elaborates on the

necessary variables to measure the characteristics of stateless persons.

• Chapter 5: Data Sources and Data Integration provides recommendations on how

different data sources, and data integration techniques, can be used to capture

statelessness statistics.

• Chapter 6: Statistical Coordination and the Data Ecosystem discusses the

importance of coordination and the national, regional and international levels. In

addition, the chapter recommends methods to build statelessness statistical capacity.

14

CHAPTER 2: LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND DEFINITION OF A

STATELESS PERSON

19. This chapter provides an overview of the international legal framework which governs the

right to a nationality, and which provides the international legal definition of a stateless person.

20. This chapter does not seek to operationalise the legal definition of a stateless person for

statistical purposes. The statistical framework for statelessness is covered in Chapter 3 of these

recommendations.

A. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON STATELESSNESS AND

THE RIGHT TO A NATIONALITY

1. International Legal Framework

21. In international law, the terms nationality and citizenship are used interchangeably and are

understood to refer to the legal bond between a person and a State. Although nationality in the

context of statelessness is not legally defined, the concept reflects a formal link, of a political and

legal character, between the individual and a particular State. This is distinct from the occasional

use of the term nationality in some countries or regions, where it is sometimes used to express

membership in a religious, linguistic or ethnic group.

24

22. The right to a nationality is enshrined in a number of international human rights

instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

25

the International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights,

26

the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Racial Discrimination,

27

the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against

Women,

28

the Convention on the Rights of the Child,

29

the International Convention on the

Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

30

and the

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

31

Under general international law, States

set the rules for acquisition, change and loss of nationality as part of their sovereign power. At the

same time, the discretion of States with regard to nationality is limited by obligations under

24

The term nationality is also understood differently in the context of the interpretation of the 1951 Convention Relating to the

Status of Refugees, where the term can also be understood as membership to a ethnic or linguistic group. For more information on

the use of the term nationality in the 1951 Convention, please see the UNHCR Handbook and guidelines on procedures and

criteria for determining refugee status, paragraphs 74 – 76.

25

UN General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 10 December 1948, 217 A (III), Article 15.

26

UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1954, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 993, p.

3, Articles 16, 24 and 26.

27

UN General Assembly, International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, 4 January 1969,

United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 660, p. 195, Article 5.

28

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, 3 September 1981,

United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1249, p. 13, Article 9.

29

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 2 September 1990, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p.

3 Articles 2 and 7.

30

UN General Assembly, International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of

Their Families, 1 July 2003, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2220, p. 3, Article 29.

31

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 3 May 2008, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol.

2515, p. 3, Article 18.

15

international treaties to which they are party, customary international law and general principles

of law.

23. International treaties establish obligations for States relating to acquisition and loss of

nationality and to standards of treatment of stateless persons. The 1954 Convention relating to the

Status of Stateless Persons (1954 Convention) is the cornerstone of international protection of

stateless persons.

32

It provides the definition of a stateless person and establishes minimum

standards of treatment for stateless people. These include the right to education, employment and

housing, and guarantees stateless people the right to an identity, travel documents and

administrative assistance. The specific protection regime set out in the 1954 Convention is

complemented by the broader human rights instruments, which apply to all persons, regardless of

their nationality status. States have the primary responsibility to respect, protect and fulfil the

enjoyment of human rights of stateless persons under their jurisdiction.

24. Specific obligations relating to prevention and reduction of statelessness are established

under the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (the 1961 Convention) and in

regional treaties.

33

The 1961 Convention requires that States establish safeguards in legislation to

address statelessness occurring at birth or later in life. The 1961 Convention also establishes

obligations for States in the event of State succession. These provisions are complemented by the

comprehensive Articles on the Nationality of Natural Persons in Relation to the Succession of

States of the International Law Commission. As a general rule, the 1961 Convention also prohibits

the deprivation of nationality where it would leave a person stateless. There are very limited

exceptions to this rule, including where nationality has been acquired though misrepresentation or

fraud.

25. The international legal framework is further complemented by the standards contained in

several regional treaties. Regional treaties in Africa,

34

the Americas,

35

Europe,

36

regions covered

by the Commonwealth of Independent States

37

and the League of Arab States,

38

recognise the right

to a nationality and establish additional obligations for States Parties relating to the prevention of

statelessness (even in some cases for countries not Party to the 1961 Convention).

2. UNHCR’s Mandate on Statelessness

26. UNHCR is the UN Agency mandated by the UN General Assembly to identify and protect

stateless people and to prevent and reduce statelessness. UNHCR’s current mandate on

32

UN General Assembly, Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, 28 September 1954, United Nations, Treaty

Series, vol. 360, p. 117 (available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3840.html).

33

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, 30 August 1961, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol.

989, p. 175.

34

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 1999, Article 6 (available at: https://au.int/en/treaties/african-charter-

rights-and-welfare-child).

35

American Convention on Human Rights,1969, Article 20 (available at: https://www.icnl.org/wp-content/uploads/treaties_B-

32_American_Convention_on_Human_Rights.pdf).

36

European Convention on Nationality, 1997, Article 6 (available at: https://rm.coe.int/168007f2c8).

37

Commonwealth of Independent States Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1995, Article 24 (available

at: https://english.dipublico.org/469/convention-on-human-rights-and-fundamental-freedoms-of-the-commonwealth-of-

independent-states/).

38

Arab Charter on Human Rights, 15 September 1994, Article 29 (available at:

https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38540.html).

16

statelessness was consolidated in 2006 by the United Nations General Assembly’s endorsement of

UNHCR’s Executive Committee Conclusion No. 106 on the Identification, Prevention and

Reduction of Statelessness and the Protection of Stateless Persons (Conclusion No. 106).

39

UNHCR’s mandate on statelessness is an equal part of its mandate and stands alongside its

protection mandate for refugees. The statelessness mandate encompasses a holistic approach to

statelessness, addressing both its occurrence and the protection of persons affected.

27. Relevant to the scope of these recommendations, Conclusion No. 106 includes specific

references to UNHCR’s work on improving the identification of stateless persons and persons of

undetermined nationality:

“(b) Calls on UNHCR to continue to work with interested Governments to engage in or

to renew efforts to identify stateless populations and populations with undetermined

nationality residing in their territory […].

and

(d) Encourages those States which are in possession of statistics on stateless persons or

individuals with undetermined nationality to share those statistics with UNHCR and calls

on UNHCR to establish a more formal, systematic methodology for information

gathering, updating, and sharing.”

B. DEFINITIONS

1. Stateless Person

28. The international legal definition for a stateless person is found in the 1954 Convention: “a

person who is not considered a national by any State under the operation of its law”.

29. In its 2006 Articles on Diplomatic Protection with commentaries, The International Law

Commission stated that the definition of a stateless person provided in the 1954 Convention is part

of international customary law, and is therefore binding on all States, regardless of whether they

are a State Party to the 1954 Convention.

40

30. Some of the key elements of the definition of a stateless person require further explanation

to facilitate its interpretation.

41

These key elements include:

“by any State”

39

The Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme. Conclusions on Identification, Prevention and Reduction

of Statelessness and Protection of Stateless Persons, 2006, no. 106, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/453497302.html.

40

See p. 49 of the International Law Commission, 2006, Articles on Diplomatic Protection with commentaries, which state that

the Article 1 definition can “no doubt be considered as having acquired a customary nature” (the Commentary is available at:

http://www.refworld.org/docid/525e7929d.html).

41

For a comprehensive overview on the interpretation of the relevant elements of the definition of a stateless persons, please

consult the Handbook on Protection of Stateless Persons, 30 June 2014, pp. 11-20 (available at:

https://www.refworld.org/docid/53b676aa4.html).

17

31. An assessment of whether a person can be considered stateless is limited to the States with

which the person has a relevant link, which include birth on the territory, descent, marriage,

adoption or habitual residence.

32. The definition of a “State” for the purposes of the definition of a stateless person is

informed by the application of the term in international law. Key criteria include a permanent

population, defined territory, government and capacity to enter into relations with other States.

42

Other factors that need to be assessed according to international jurisprudence include the

effectiveness of the entity, the right of self-determination, the prohibition of on the use of force

and the consent of the State which previously exercised control over the territory in question.

“not considered as a national… under the operation of its law”

33. For the purpose of interpreting the definition, the reference to “law” should be interpreted

broadly to encompass not just legislation, but also ministerial decrees, regulations, orders, judicial

case law (in countries with a tradition of precedent) and, where appropriate, customary practice.

34. Establishing whether an individual is “not considered as a national under the operation of

its law” is a mixed question of fact and law. An individual’s nationality or stateless status depends

not only on the law as written, but also as applied by the authorities of the State in question.

2. Person of Undetermined Nationality

35. The term person of undetermined nationality is not defined in international law. However,

UNHCR’s Executive Committee Conclusion No. 106, endorsed by the UN General Assembly

(GA) Res. 61/137 of 19 December 2006, called on UNHCR to work with governments to identify

stateless populations and populations of undetermined nationality, therefore the definition of this

population is also important to understand existing statistical practice.

36. The Executive Committee Conclusion further encouraged States to share available

information on populations of undetermined nationality with UNHCR and called on UNHCR to

establish a more formal and systematic methodology for information gathering, updating and

sharing. Since 2009, UNHCR has been reporting global statistics on the number of stateless

persons and persons of undetermined nationality.

37. For the purposes of identification and data collection, UNHCR defines persons with

undetermined nationality as persons in situations where a preliminary review has shown that it is

not yet known whether they possess a nationality or are stateless. This preliminary review is not a

formal government procedure to determine and grant a legal status. As such, apart from

governments, these preliminary reviews can be conducted by a range of stakeholders including

UNHCR, civil society organisation, academics and others. UNHCR only reports people as being

of undetermined nationality if the persons concerned:

• Lack proof of possession of any nationality; and

42

Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States, 1933 (available at:

https://www.ilsa.org/Jessup/Jessup15/Montevideo%20Convention.pdf).

18

• Have links to more than one State on the basis of birth, descent, marriage, adoption

or habitual residence; or

• Are perceived and treated by authorities in the State of residence as possessing links

which give rise to a claim of nationality of another State based on specific elements

such as historic ties, race, ethnicity, language or religion.

38. The term “persons with undetermined nationality” is used as a temporary identification

category and generally does not lead to the provision of legal status, access to protection or

services. It is expected that a more in-depth review of the situation of those in this category will

be undertaken to determine whether they have the nationality of a State or are stateless.

3. Potentially Associated but Distinct Groups

39. Being stateless is a distinct legal status and only persons meeting the criteria set out in the

definition provided in the 1954 Convention can be considered as a stateless person. Other

population groups, some with defined legal statuses, are often considered or mentioned in the

context of discourse on statelessness and may also be stateless but are not necessarily so. These

potentially associated but distinct groups include:

40. Refugees: According to the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol,

43

a refugee is a person

“who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality,

membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his

nationality, and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of

that country”. Refugees can also be stateless but are not so automatically, as their country of origin

may still recognise them as nationals, even if they do not enjoy the protection of that country.

Likewise, stateless persons are not by definition refugees. However, stateless persons may also be

refugees if they have crossed an international border based on a well-founded fear for persecution

on the grounds set out in the 1951 Convention. Similarly, stateless persons may also be asylum

seekers if they submitted an application for refugee status and their claim is still being assessed.

41. Internally displaced persons (IDPs): Internal displacement describes the situation of

persons who have been forced or obliged to leave or abandon their homes and who have not

crossed an international border.

44

Similar to refugees, IDPs can also be stateless but are not so by

definition, it depends on whether they are recognised as nationals by a State.

42. Migrants: There is no international legal definition of a migrant, but for statistical purposes

the term is defined in the UN Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration as a “any

person who changes his or her country of usual residence”.

45

As such, a stateless person can

become a migrant when she or he leaves their place or country of residence, however, not all

migrants are stateless. In the context of statelessness, undocumented migrants are often discussed.

43

UN General Assembly, Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 31 January 1967, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 606,

p. 267 (available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3ae4.html).

44

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, 22 July 1998 (available at:

https://www.refworld.org/docid/3c3da07f7.html).

45

United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Recommendations on Statistics of

International Migration, Revision 1, United Nations, New York, 1998 (available at:

https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesm/seriesm_58rev1e.pdf).

19

Although in certain contexts, migrants who lack proof of legal identity may be unable to prove

relevant links to any country, may be at risk of statelessness, especially in combination with other

factors (see paragraphs 44 and 45), not all undocumented migrants should be considered as

stateless and further assessments are required to determine whether a person meets the criteria set

out by the legal definition of a stateless person. Nomads who migrate across international borders

and have links with more than one country may face similar issues when unable to prove their

nationality or relevant links to a country or countries. However, not all nomads without proof of

nationality/identity should be considered as stateless.

43. Documentation, especially nationality documentation, or the lack thereof is often also

discussed as a defining criterion for the determination of a person’s nationality status. In

international law, there is no definition of an undocumented person. Documentation which

establishes (part of) a person’s identity, or the lack thereof, can be important tools to assess a

person’s nationality, or lack thereof. As such, situations where a person does not have any proof

of legal identity which is defined as a credential, such as birth certificate, identity card or digital

identity credential that is recognised as proof of legal identity under national law and in accordance

with emerging international norms and principles,

46

can be related to situations of statelessness.

However, a recognised stateless persons can have a legal identity and documentation, and an

undocumented person, although perhaps (temporarily) unable to prove it, can be recognised as a

national by a State. Although proof of identity in certain contexts may be required to access

nationality (see paragraphs 48-49), undocumented persons are not by definition stateless. A careful

assessment of an individual’s situation is often required to understand whether an undocumented

person may be stateless if that person is not able to (re)acquire proof of legal identity.

C. CONTRIBUTORY CAUSES OF STATELESSNESS

44. Nationality is usually acquired at birth, automatically or following an administrative

process, either through descent (born to a parent who confers nationality to the child) or by birth

on the territory. However, several factors exist of which one or more can result in or contribute to

statelessness. Table 2.1 provides an overview of the main contributory causes of statelessness.

Table 2.1 Contributory Causes of Statelessness

Discrimination on the

basis of race, ethnicity,

religion or language.

The exclusion of certain groups or populations from the citizenry of a

State based on discriminatory grounds is linked to many (large-scale)

protracted statelessness situations. States can also deprive citizens of their

nationality through changes in law using discriminatory criteria that leave

entire segments of the population stateless. Most of the known stateless

populations belong to racial, ethnic, or religious minority groups.

47

46

UN operational definition of legal identity developed by the United Nations Legal Identity Expert Group.

47

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), This is our Home: Statelessness Minorities and their Search for Citizenship,

3 November 2017 (available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/our-home-stateless-minorities-and-their-search-citizenship).

20

Gender discrimination in

nationality laws

Gender discrimination in nationality laws, and related administrative

procedures such as birth registration,

48

is another cause of childhood

statelessness. Currently, laws in 24 countries in the world do not allow

women to confer nationality to their children on an equal basis as men.

Consequently, when the father is stateless, unknown, missing or deceased,

unable or unwilling to take the steps needed to confer his nationality, the

child can be left stateless.

49

Gaps in nationality laws

If laws are not drafted in accordance with international standards or if they

are incorrectly applied, persons may be left stateless. Foundlings, or

abandoned children of unknown parents, in countries where nationality can

only be acquired through descent and for whom there is no legal safeguard

granting them nationality of the State on whose territory they are found, is

one example of such a gap.

Conflicting nationality

laws between countries

Conflicting nationality laws between countries can also pose risks of

statelessness for persons. Conflicting laws can leave persons with link(s)

to two or more countries who have conflicting nationality legislation not

being able to access any nationality. One example is a child born abroad in

a country where nationality is not granted solely based on birth on the

territory, and the parent(s)’s country of origin does not allow conferral of

nationality for children born abroad.

State succession and

changing borders

In situations of State succession and changing borders, people can be left

stateless when they are unable to access nationality of the successor State,

because nationality laws have been drafted in a restrictive manner, or the

individuals are unable to prove their link to the new country.

Loss or deprivation of

nationality

Statelessness can also be caused due to loss or deprivation of nationality.

When such legal provision depriving a person of their nationality are

applied automatically or without a safeguard against statelessness, persons

may be left stateless. For example, in some countries citizens can lose their

nationality automatically by operation of the law due to an extended period

abroad, even if this would leave them stateless.

Lack of proof of

nationality

Lack of proof of nationality may prevent a person from being able to

prove that they are a national of a State. Being undocumented is not the

same as being stateless but may present certain risks. A person who for

example does not have a birth certificate, may be unable to prove place of

birth or parentage, which are key elements needed to claim an entitlement

to nationality. Certain population groups can be left at risk of

statelessness because of their lack or inability to acquire proof of

nationality. This can include refugees living in protracted exile, border-

dwelling communities, and nomadic groups.

Administrative and

financial barriers

Due to specific administrative or financial barriers, a person may be left

unable to meet the administrative requirements necessary to access a

nationality that they legally would be entitled to, for example the inability

to access (late) birth registration due to administrative fines/fees which

48

See the UNHCR and UNICEF Background Note on Sex Discrimination in Birth Registration, 6 July 2021 (available at:

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/background-note-sex-discrimination-birth-registration).

49

For more information on gender discrimination in nationality laws, see the UNHCR Background Note on Gender Equality,

Nationality Laws and Statelessness 2022 (available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/6221ec1a4.html).

21

the parents cannot afford, children not being registered with the

consulates of the country of nationality of their parents, or in situations

where persons are unable to prove the nationality of their deceased

parents due to lack of documentation and/or poorly functioning civil

registration systems.

45. Causes of statelessness are very often context specific. A careful analysis of a countries’

history, legal and policy frameworks, and the links that individuals and groups have with other

countries is required to understand which factors are relevant to be assessed within a specific

country context. In many situations, one of the contributing factors to statelessness is enough to

leave a person or entire populations stateless (e.g., ethnic minorities being excluded by law from

accessing nationality) whereas in other situations, a combination of factors will lead to a person or

group being left stateless.

D. IMPACT OF STATELESSNESS ON IMPACTED POPULATIONS

46. Statelessness is, in simple terms, the lack of any nationality. The individual right to a

nationality has been recognised as part of international human rights law, further supported by

several regional human rights instruments. The right to a nationality, apart from being an important

human right in and of itself, often serves as a gateway to the enjoyment of other human rights in

practice.

47. Aside from being denied the right to a nationality, statelessness can have serious

consequences on all aspects of a person’s life and their family members. Stateless persons,

depending on the context, are often barred from accessing basic services and rights, lack economic

opportunities, and can be the victims of exploitation and abuse and arbitrary detention. Some of

the common consequences of statelessness include: a lack of socio-economic rights including

education, health care, formal employment, the right to own a business, access to housing, access

to social welfare systems etc. Stateless persons are also often barred from social and political rights

including the right to get legally married and political participation. Stateless persons may also

lack freedom of movement and to travel internationally.

E. SOLUTIONS TO STATELESSNESS

48. In simple terms, being stateless is the absence of a nationality. A number of actions can be

taken to prevent statelessness from occurring in the first place. The solution to statelessness is the

acquisition or confirmation of nationality of a State.

49. There are several ways in which statelessness can be prevented or resolved, including:

a. Through a law reform whereby the State in question closes legal gaps which lead

to statelessness and involves the inclusion of legal safeguards to prevent

statelessness (prevention).

22

b. Stateless people may acquire nationality through naturalisation. Some States have

specific provisions in place for facilitated naturalisation for stateless persons, in line

with the 1954 Convention, including shortened residency requirement and waivers

of administrative fees (acquisition).

c. Targeted nationality campaigns can be undertaken by States with the objective of

resolving the statelessness situation on the territory through the granting of

nationality. Such campaigns target longstanding stateless populations (acquisition).

d. Nationality verification procedures assist individuals who face difficulties

obtaining proof of their nationality status (confirmation).

F. STATELESSNESS STATUS DETERMINATION

50. For stateless populations in a migratory context, States are advised to establish a

statelessness determination procedure (SDP), which aims specifically at determining if a person is

stateless.

50

These procedures are conducted with the objective of identifying stateless persons and

granting stateless persons rights related to their recognised status.

51

For stateless persons who are

not in a migratory context, temporary protection status through an SDP is generally not

recommended, but rather access to nationality through grant, confirmation or verification are

preferred.

51. So far only a limited number of States

52

worldwide have established a SDP. However, there

is a growing interest among States to establish specific mechanisms for the identification of

stateless persons. During the 2019 High Level Segment on Statelessness, 33 States pledges were

made to implement a statelessness determination procedure by the end of 2024 or improve existing

procedures.

53

Even though these procedures are not aimed at collecting data on statelessness, they