DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 365 052

EC 302 677

AUTHOR

Roger, Blair; And Others

TITLE

Schools Are for All Kids: School Site Implementation.

Level II Training. Participants Manual.

INSTITUTION

San Francisco State Univ., CA. California Research

Inst.

SPONS AGENCY

Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative

Services (ED), Washington, DC.

PUB DATE 19 Feb 92

CONTRACT

G0087C3056-88

NOTE

149p.; For related material, see EC 302 678-679.

PUB TYPE

Guides Classroom Use

Teaching Guides (For

Teacher) (052)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC06 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

Cooperative Learning; *Disabilities; *Educational

Planning; Elementary Secondary Education; Group

Dynamics; Grouping (Instructional Purposes);

Individualized Education Programs; Inservice Teacher

Education; *Leadership Training; *Mainstreaming;

Participative Decisioh Making; Postsecondary

Education; *Program Development; School

Restructuring; Social Integration; Staff Role;

Teacher Role; Teamwork; Workshops

ABSTRACT

This training manual for a 2-day workshop was

developed from the perspective that a fully inclusive society will

evolve only if there are schools which embrace all children,

including those with disabilities. Each participating team first

considers their school's current goals and progress made towards full

inclusion, and then establishes goals and identifies strategies and

resources to support continued movement towards full inclusion.

Objectives in Section I of the training manual involve identifying

and describing key components of integration, a rationale for school

restructuring, the role of the school site integration task force,

and the role of the integration facilitator, and team teaching and

peer coaching strategies. Section II focuses on group skills,

leadership and participatory management, decision making, conflict

management, effective meetings, student placement, and systems

change. Section III covers educational goals for students with severe

disabilities, curriculum adaptation, student grouping strategies,

cooperative learning strategies, and factors which facilitate

integration. Section IV addresses the Individualized Education

Program, functional assessment, team action plans, a common vision

for integration, and establishment of an individual school site

integr-Aion plan. The manual provides background information,

self-evaluation questionnaires, group and individual learning

activities, and note-taking guides. (Contains 18 references.)

(JDD)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.

***********************************************************************

SCHOOLS ARE FOR ALL KIDS:

SCHOOL SITE IMPLEMENTATION

LEVEL II TRAINING

PARTICIPANTS MANUAL

Sponsored by:

The California Research Institute

A Federally Funded Research and Technical

Assistance Project on the Integration

of Students with Severe Disabilities

Written by:

Blair Roger

Consultant

Integrated Services for

School, Community, & Work

MEW-

U S DEPARTMENT OF

EDUCATION

Orhce 0 Ed.cat.ona. pesealo,

and onDrOvement

EDUCATIONAL

RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER ERIC.

7....1'Ks document has Peen

redoduced as

recemad Iom the oe,son

organaahon

ohcpnahng 4

Mo,s, changes have oeen

made tc moroye

,ewocluchon auahty

Po.nts of y.e*

op.mons stated ,rtInS

u

ment dd Sot necessahh

,ewesent offcna,

OEFh poso.on dt palCy

Renee Gorevin

California Implementation

Sites Manager

TRCCI, PEERS, &

California Deaf Blind Services

Meredith Fellows

Consultant

Effective Instruction & Supervision

Dotty Kelly

Technical Assistance Coordinator

California Research Institute

This program was developed by the California Research Institute, funded by the Office of Special

Nucation and Rehabilitation cooperative agreement number G0087C3056-88.

The information

presented herein does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States Department of

Education and no official endorsement should be inferred.

4

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

Table of Contents

SCHOOLS ARE FOR ALL KIDS

SCHOOL SITE IMPLEMENTATION

PAGE

INTRODUCTION

i

1

Agenda Day 1

ii

What Makes a Class "Work"?

iii

I

Format & Philosophy of Program

iv

Progam Objectives

v

Overview Parameters of Full Inclusion

viii

SECTION I

1-1

Objectives

1-1

Strategies for Building Inclusive Schools

1-2

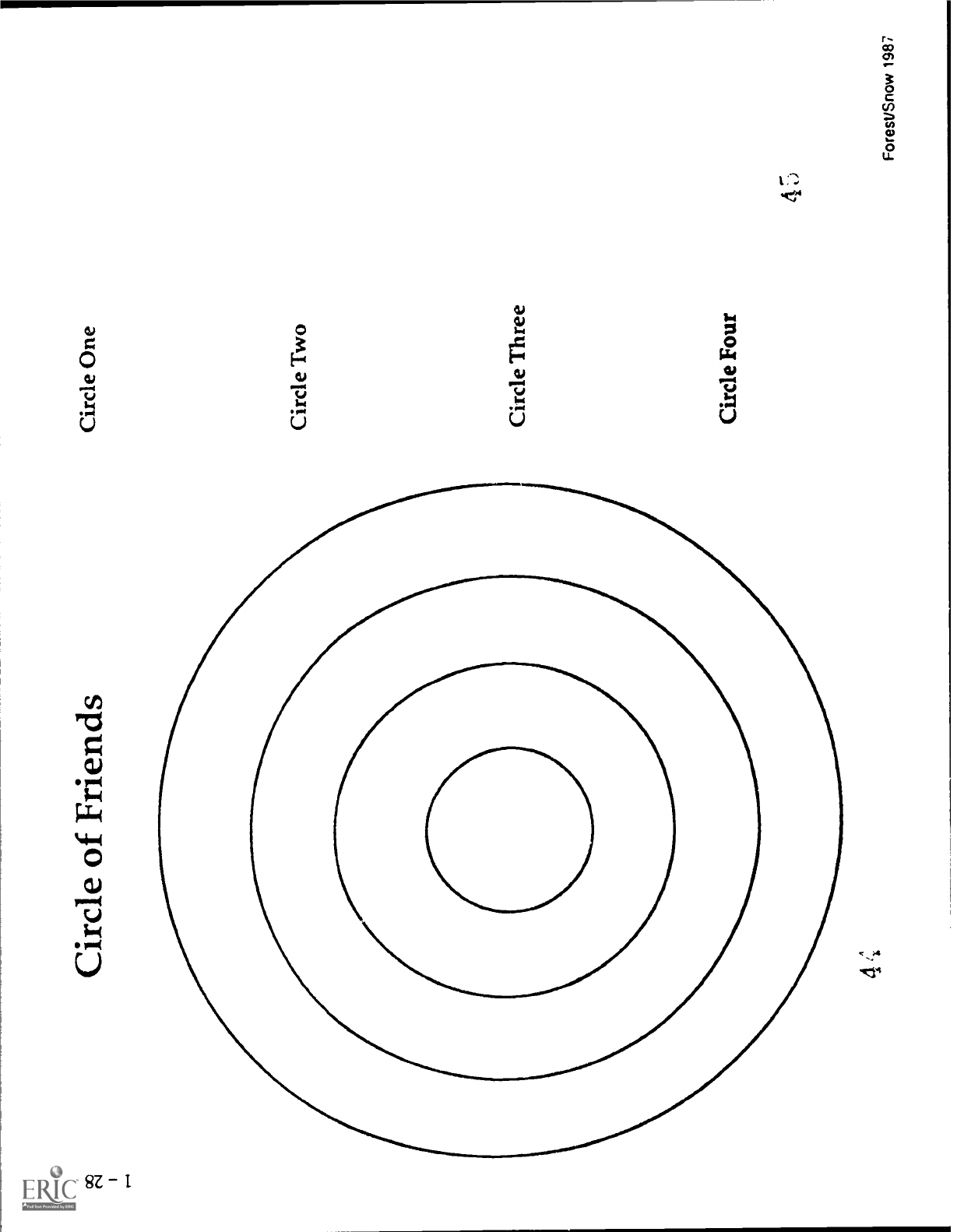

Circle of Friends

1-28

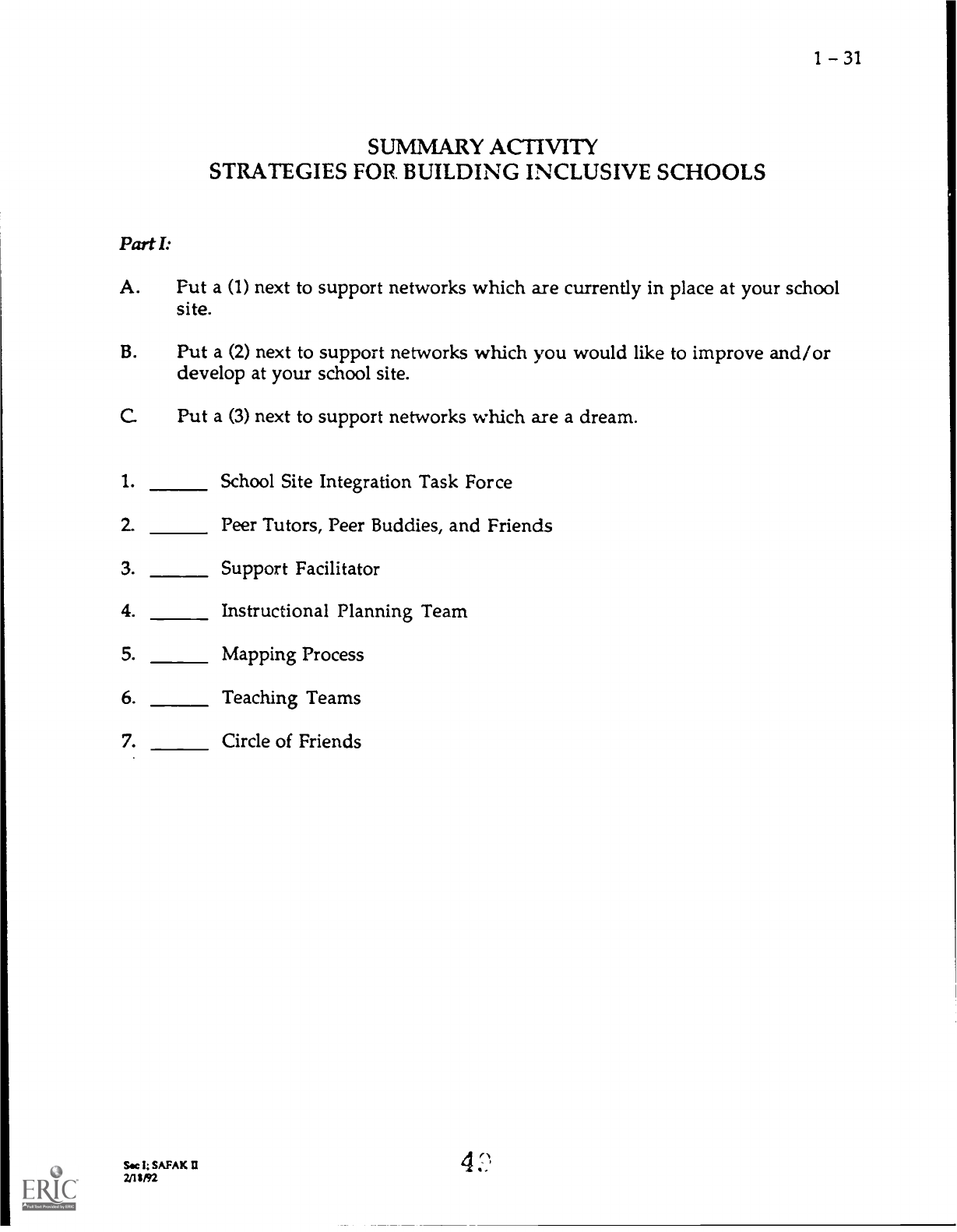

Summary Activity Strategies for Building Inclusive Schools

1-31

School Site Team Planning

1-33

SECTION II

2-1

Objectives

2-1

What's Wrong With This Picture?

2-2

Roles in the Integration Process

2-4

Making Meetings Work

2-7

Student Planning Team Meeting

2-9

The Change Process

2-15

Closure Activity Story Board

2-22

SECTION III

34

Agenda Day 2

3-2

The Interview Activity

3-3

Objectives

3-4

Promoting Inclusive Schools Activity

3-5

Assumptions for Integrated IEP Process

3-6

Cunicular Goals & Adaptations

3-7

Grouping Strategies

3-12

Cooperative Groups

3-23

SECTION IV

44

Objectives

4-1

Individualized Program Planning Process

4-2

Group Vision

4-23

Final Action Plan

4-24

Evaluation

4-29

Additional Readings List

4-30

Cova Parc SAFAK II

2/19O2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several individuals offered guidance, insight, technical assistance and support

during the design of SCHOOLS ARE FOR ALL KIDS: SCHOOL SITE

IMPLEMENTATION. We would like to express sincere thanks to the following

individuals for their contributions.

CRI Staff

Dotty Kelly

Patricia Karasoff

Felicia Farron-Davis

Lori Goetz

Susan Beckstead

Pam Hunt

Morgan Alwell

Other

Dru Stainback

Jodi Servatius

Linda Brooks

Louise Ziberski

Bonnie Mintun

Ida Denier

Tom Neary

Ann Halvorsen

Lynn Smithey

Laurie Triulzi

Debbie Zehnder

Support Services

Swift Pense

Charles Ragland

Teclmical Assistance Coordinator

Project Coordinator

Research Assistant

Best Practices Research Development

Specialist

Research Site Manager

Research Coordinator

Teacher, Berkeley Unified School District

& CRI Research Assistant

Educational Consultant, SDSU

California State University, Hayward

Teacher Yolo County Office of Education

Teacher Davis Unified School District

Parent

Prindpal Valley Oak Elementary School

PEERS Project

PEERS Project

PEERS Project

Teacher, Berkeley Unified School District

Special Education Teacher, Santa Cruz

County Office of Education

CRI Office, Support Staff

Video Consultant

IINTA DUCTIT N

Introduction; SAFAK

2/111/92

SCHOOLS ARE FOR ALL KIDS

SCHOOL SITE IMPLEMENTATION

AGENDA DAY 1

INTRODUCTION:

Introduction Activity

What Makes a Class Work? Activity

Format & Philosophy of Program

Overview Workshop Objectives

Overview Parameters of Inclusive Programs

(Mini Lecture & Discussion)

SECTION I:

Overview Objectives

Jigsaw Activity Strategies for Building Inclusive

Schools

Circle of Friends Activity

Kids Belong Together Video

Team Prioritizing and Planning Activity

Lunch

SECTION II:

Overview Objectives

What's Wrong With This Picture?

Roles in the Integration Process

Making Meeting Work

Student Planning Team Meeting

School Site Team Planning

Strategies to Facilitate Change Activities

Closure Activity

Introduction; SAFAK n

392

iii

ACTIVITY

CHARACTERISTICS IDEAL CLASSROOM

Take 5 minutes to brainstorm the characteristics of an ideal dassroom (what's going

on to make it "work") with your group. Share your ideas with the large group.

Inuoduction; SAFAK 11

2/1S/92

i v

PHILOSOPHY OF PROGRAM

The training has been developed from the prospective that a fully inclusive society

will evolve only if we have schools which embrace all children. The program

attempts to establish this vision as a goal. However, care has been taken to assure

that no participant is made wrong because his or her school isn't more fully

integrated. This is accomplished by asking each team to first consider their school's

current goals and progress made towards full inclusion and then to establish goals,

identify strategies and resources which will support their continued movement

towards full inclusion. Thus all teams can be successful in the program.

The program has been developed from the point of view that workshop attendees

must be active participants in their own learning. Application of the skills and

attitudes in the program will be most likely when participant teams make realistic

plans together, form a group commitment to realizing those plans and are assisted

in locating the resources to support them.

Introduction; SAFAK 1:1

2/11/92

PROGRAM OBJECTIVES

SCHOOLS ARE FOR ALL KIDS

School Site Implementation

Level II Training

Participants will:

1.

Increase instructional leaders' awareness of principals regarding the

universal advantages of integrating students with mild to severe

disabilities

into their school sites.

2.

Develop the commitment to the concept of equal access to learning

for all

students.

3.

Identify new roles for special and general educators as instructional leaders

for all kids.

4.

Develop plans to implement integrated programs in home schools.

5.

Increase their knowledge of effective practices, models and resources

for

implementing the integration of students with mild to severe disabilities

into their home schools.

6.

Identify specific strategies for team-building and developing collaboration

between general and special educators and parents to ensure that all

students meet their educational goals and objectives in the least restrictive

environment.

7.

Identify curricular and instructional adaptations for the delivery of effective

programs for all students.

8.

Identify strategies specific to the development of their school site plan for

restructuring special and general education service delivery to provide

quality education for all children.

9.

Increase their knowledge of systems change and strategies for facilitating

personal and organizational growth.

10.

Increase commitment and identify strategies to develop schools and

classrooms with a sense of community, a belief that everyone belongs, is

welcomed and has gifts and talents to offer.

introduction; SAFAK 11

2/18/92

v i

WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES ACTIVITY

1.

Which goals listed here are you most familiar with?

2.

The goals that interest me most and or will probably provide me with the

most information are?

Introduction; SAFAK D

713/92

vii

THE PATH TOWARDS FULL INCLUSION

AN OVERVIEW OF INTEGRATION

NOTE TAKING PAGE FOR LECTURE & GROUP DISCUSSION

baroducoon; SAFAK A

2111192

WHAT IS INTEGRATION?

INTEGRATION IS:

1.

All children learning in the same schools with the necessary services and

supports so that they can be successful there.

2. Each child having his or her unique needs met in integrated environments.

3. All children participating equally in all facets of school life.

4. An integral dimension of every child's educational program.

5. Labeled and nonlabeled children having facilitated opportunities to interact

and develop friendships with each other.

6. A new service delivery model for special education which emphasizes

collaboration between special education and general education.

7.

Providing support to general education teachers who have children with

disabilities in their classrooms.

8. Children learning side by side even though they have different educational

goals.

*Adapted from Douglas Biklen

Introduction; SAFAK U

2/11492

viii

WHAT IS INTEGRATION?

INTEGRATT.ON IS NOT:

ix

1.

Dumping children with challenging needs into general education classes

without the supports and services they need to be successful there.

2. Trading the quality of a child's education or the intensive support service the

child needs for integration.

3.

Ignoring each child's unique needs.

4.

Sacrificing the eduction of typical children so that children with challenging

needs can be integrated.

5.

All children having to learn the same thing, at the same time, in the same

way.

6.

Doing away with special education services or cutting back on special

education services.

7.

Expecting general education teachers to teach children who have challenging

needs without the support they need to teach all children effectively.

*Adapted from: Douglas Biklen

A LOOK AT FULL INCLUSION ACROSS AGE GROUPS

Infant Through

Integrated Daycare & Pre-School

Preschool Age

Programs

Early Elementary

Home School

School Age

General Education Classroom

Intermediate &

Middle-School Age

High-School Age

Post-Secondary Age

Home School

General Education Classroom(s)

Community Based Instruction

Vocational Instruction on Campus &

in the Community

Home School

General Education Classrooms

Community Based Instruction

Integrated Work

Transition Planning

Community College Campus

Integrated Work

Training for Community &

Independent Living Skills

Sailor, W., et al. (1989). Comprehensive local schools: Regular education for all students with

disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

xi

CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE SCHOOLS

Safe, Orderly, and Positive Learning Environment

Strong Instructional Leadership

High Expectations

Clear School Mission

Opportunities to Learn and Time on Task

Frequent Monitoring of Student Progress

Parental and Community Involvement

Curriculum Continuity

Multi-cultural Education

Intro luerion: SAFMC

n

2/1102

xii

"The process toward integration has followed

a well-worn path traveled by several gener-

ations of people classified as disabled in

nearly the same sequence of graduated

steps experienced by several generations of

black sftidents.

The process seems to have

been: identify, categorize, separate, equalize,

integrate.

The process for blacks was called

desegregation: for people with disabilities it

is called integration."

Sailor & Guess, 1983

1 - 1

Section I

A strong and sturdy foundation is needed to begin construction of any building in

order to ensure its stability and longevity. Any shortcuts or compromises in design

or materials will surely jeopardize the safety and effectiveness of the structure in the

long run.

When building an inclusive school to meet the needs of all students certain

characteristics, commitment, leadership and philosophy need to be in place to create

that "sense of community." The "foundation" for creating an inclusive school will

be discussed in this section. We will begin by exploring key components of an

inclusive school.

Strategies to support teachers and students in inclusive schools will be discussed.

Support networks within a school provide the teachers, students, and staff with the

assistance they need to teach, learn and work together effectively. Teams are

developed to aide in consultation, collaboration, problem solving and student

program development. Students and parents are important contributing members

to a networks of support. Finally we will discuss the utilization of resources in place

at your school and begin to identify new resources.

Objectives:

1.

Describe key components of Integration.

2.

Describe a rationale for the restructuring of schools.

3.

Describe key components of classrooms that "work."

4.

Identify the role of a school site integration task force and a students centered

team in promoting integration and inclusion in general education.

5.

Identify team teaching and peer coaching strategies.

6. Describe the role of the integration facilitator in your school.

7.

Identify strategies to utilize peers in your school, including mapping Circle of

Friends, peer tutors and peer buddies.

Sic I; SAFAK ii

2n Sin

1 2

ACTIVITY

SUPPORT NETWORKS

STRATEGIES TO SUPPORT STUDENTS AND TEACHERS

IN DEVELOPING INCLUSIVE SCHOOLS

Number off from one to six in your school site team. Join workshop participants

who have the same number to form an expert group. Take the next 25 minutes to

complete your reading and discuss with your expert group how you can best present

the information back to your school site team. Indude personal examples of how

you have seen this strategy work effectively.

Return to your school site team and take the next 40 minutes for each expert to

share strategies with the team.

S4e 1; SAFAK

2/1S/92

1 3

NOTE TAKING GUIDE

STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING INCLUSIVE SCHOOL

SCHOOL SITE INTEGRATION TASK FORCE (1) PEER TUTORS, PEER BUDDIES, AND FRIENDS

(2)

SUPPORT FACILITATOR (3)

INSTRUCTIONAL PLANN NG TEAM (4)

MAPPING PROCESS (5)

TEACHING TEAMS (6)

SecI;SAFAKfl

/92

1 - 4

(fl

SCHOOL SITE INTEGRATION TASK FORCE

A school site integration task force brings people together to work collaboratively to

develop plans for creating an inclusive school. In some school buildings, a school

site planning team that provides direction and leadership already exists. In these

situations, it is most efficient to infuse integration as an agenda item for this pre-

existing team and develop a sub-committee or task force of the existing planning

team rather than create a new structure.

Membership of the task force should include at least key parents, key general and

special education teachers, and the building administ-ator. The participation and or

input of individuals who are responsible for implementation as well as individuals

who are willing to solve problems in a positive and creative manner should be

encouraged. Recruitment of individuals who are respected by their peers and are

representative of various factions within the school facilitates communication and

feedback from the larger school community.

Achieving change requires bringing people together - collaborative teamwork.

Maintaining change requires including in the planning process the people

responsible for implementation, so that ownership is instilled and a base of support

is built. A participation approach to change has the advantages of ownership, group

problem solving, division of labor, and greater connections facilitative of building

constituencies (York & Vandercook, 1989).

In addition to serving as a general advocacy group for integration, the purpose of the

task force is to help all individuals involved with the school gain a better

understanding of the why and hows of developing and maintaining an integrated,

caring, and inclusive school community. To do this the task force is often charged

with several duties. One is to gather background information in the from of books,

articles, and videotapes on the subject. These can be recommended to and shared

with school personnel, students, parents, and school board members. A special

section of the school library might be designated to maintain all the materials

gathered. Also, when gathering background information, key task force members or

other school personnel may want to visit inclusive schools in one's own or nearby

school district and organize attendance at professional conferences and workshops

on full inclusion strategies.

A second purpose of the task force is to organize and conduct information sessions

for parents and school personnel where people knowledgeable and experienced in

full integration can discuss reasons and provide suggestions as to how it might be

accomplished. It is important that the key people invited to share information have

direct experience in full-time regular class integration. Usually a combination of

parents, students, teachers, and administrators from a school system that has

successfully integrated their classrooms can he more "believable" ,..1c1 effective than

Sec I; SAFAK

21111)92

1 - 5

hearing only from "experts."

Some schools have the same information sessions for

parents, educators, students and administrators, which involves everyone "sitting

down together" rather than each group communicating only among themselves.

Use of outside consultants should be exercised cautiously so that building site

personnel do not consider themselves lacking the competence to implement change

or lacking control over the change process.

A third purpose of the task force is to establish an integration plan based on a school

site needs assessment that identifies specific goals and objectives for achieving full

inclusion. This plan usually includes how the resources and professional and

nonprofessional personnel in special and general eduction can be utilized to

provide reduced teacher/pupil ratios, team teachers, consultants, teacher aides, and

support facilitators in the mainstream of regular education. In addition, the

integration task force can assist in developing an inservice plan on strategies which

facilitate full inclusion (e.g. cooperative learning, peer programs, student planning

teams, ability awareness education, etc.). Finally, the integration task force should

develop a process for ongoing evaluation of the integration plan.

By establishing such a task force to help achieve inclusive schooling, community

members, students, and a variety of personnel within a school can become involved

and take ownership and pride in achieving a fully integrated school.

Adapted from:

York, J. & Vandercook, T. (1989). Strategies for Achieving an Integrated Education for Middle School

Learners with Severe Disabilities. In York, J., Vandercook, T., Macdonald, C.,& Wolf, S.

(Eds.) (1989). Strategies for Full Inclusion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Institute on

Community Integration.

Stainback, S. & Stainback W. Inclusive Schooling. In Stainback, W. & Stainback S. (Eds.) (1990).

Support Networks for Inclusive Schooling. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brookes Publishing

Co.

Sae I; SAFAK ll

2/111A2

2 AT

1 - 6

(2)

PEER TUTORS, PEER BUDDIES, AND FRIENDS

Thousand and Villa discuss instructional practices utilizing "peer power" as a

major resource which can facilitate the eduction of all learners within regular

education. "In our estimation, peer power is a key variable in meeting the needs of

a diverse student population within general education settings."

Peer tutoring partnerships are a cost-effective way for teachers to increase the

amount of individualized instructional attention available to select or all students

within their classrooms (Armstrong, Stahlbrand, Conlon, & Pierson, 1979). By using

same-age and cross-age tutors, teachers can add instructional resources to the

classroom without adding additional adult personnel.

Peer tutor systems. Same age and cross-age peer tutoring systems are two

forms of peer power upon which heterogeneous schools need to capitalize. In a

review of the literature regarding peer tutoring, Pierce, Stahlbrand, and Armstrong

(1984) have cited the benefits of peer tutoring to twees, tutors, and instructional

staff. What follows is a discussion of some of these benefits.

Benefits to tutees. Clearly, students who receive tutoring receive increased

individualized instructional attention as a consequence of the one-to-one teaching

arrangement with a peer; and research has consistently demonstrated that students

make significant academic gains as a result of tutorial sessions with same-age or

cross-age peers. Additionally, there is the opportunity for a positive personal

relationship to develop between the tutor and the tutee; and the tutor may become a

positive role model, demonstrating interest in learning and desirable interpersonal

skills. Finally, success experienced by the tutee in the tutorial situation promotes

enhanced feelings of self-esteem (Pierce et al., 1984).

Good and Brophy (1984) have suggested that peers trained as tutors may be

more effective than adults in teaching particular content such as mathematical

concepts (Cohen & Stover, 1981). They further speculate that their superior

effectiveness lies in their tendency to be more directive than adults; their familiarity

with the material and their resultant understanding of the tutee's potential

frustration with the materials, and their use of more meaningful and age-

appropriate vocabulary and examples.

Benefits to tutors. There is an old adage, "If you can teach it, you know it."

For the tutor, the act of teaching and the preparation required to effectively teach a

concept or skill can lead to a higher level of reasoning and a more indepth

understanding of the material being taught (Johnson, Johnson, Holubec, & Roy,

1984). Like the tutee, the tutor's self-esteem may be enhanced, in this case by

assuming the high status role of teacher (Gartner, Kohler & Riessman, 1971). The

social skills of the tutor also may be increased as a direct result of the modeling,

coaching and role playing of effective communication skills (e.g., giving praise,

giving constructive criticism) they are expected to use in tutorial sessions (Pierce, et.,

1984).

Arranging peer tutoring systems. Peer tutoring systems can be established

within a single classroom or across an entire school. Systems which have been

demonstrated to be effective have well-developed strategies for recruiting, training,

See 1; SAFAK 11

2/1S/92

1 - 7

supervising and evaluating the

effectiveness of

peer tutors (Cooke, Heron, &

Heward, 1983: Good & Brophy, 1984, Pierce, et

al., 1984). Frequently, the tutor and

supervising teacher formulate and sign a contra.t

which spells out in detail the

performance expectations of the tutor and the

supervisor. At the high school level,

courses have been taught

and credit has been given for peer tutoring activities.

Peer support networks and peer buddies.

Historically some students,

particularly student with disabilities, have been

excluded from certain aspects of

their school life (e.g., school clubs and

other co-curricular activities, school dances,

attendance at athletic events). Peer support groups or

networks have been

established in some schools and have proven to

be effective in enabling these

students to participate more fully in the life

of their schools.

The purpose of a peer support network is to enrich

another student's school

life. Peer support networks are comprised

of students who have volunteered, been

recommended by teachers or counselors, or been

recruited by other students in the

network to serve as "peer buddies." Students

and school personnel have stressed

the importance of trying to include as peer tutors

those students who are active in

school activities or who are perceived as

having "high social status" among their

peers. Peer support networks are

effective because the peer buddies are active in

school activities and have a social network

and therefore, can facilitate the

introduction, inclusion and active involvement of

students who typically might not

be invited or volunteer to participate in

non-academic school functions.

Peer buddies are different from peer tutors in that

their involvement with

other students is primarily non-academic. The

diversity of support which peer

buddies can provide other students is limitless.

For example, a peer might assist a

student with physical disabilities to use and get

items from her locker, "hang out" in

the halls with a student before or after classes, or

walk to classes. A peer buddy

might accompany a student to a ball game after

school or speak to other students,

teachers or parents about the unique physical,

learning, or social challenges that they

see their friend facing

and meeting on a daily basis.

The benefits of peer tutoring programs dted above also apply to peer support

systems. Peer buddies assist the person

with whom they are paired and the larger

school community to acquire skills to more

effectively communicate and interact

socially with one another. Peer support networks

have helped to make

heterogeneous schools places where students' learning is

expanded to include an

understanding of one another's lives.

Peer membership on instructional planning teams. Peers

also have proven

to be invaluable members of

instructional planning teams for students with disabil-

ities. They are particularly helpful in identifying

appropriate social integration goals

to be included on a student's

instructional planning team. A special education

administrator who routinely includes peers in IEP

development has stated:

"Although we have emphasized socializaon and inclusion for years,

it

never really took off until we

turned to the students and asked for their help. We

previously were leaving out of the planning process

the majority of the school's

population" (DiFerdiando, 1987).

Friendships and supportive relationships. Supportive

relationships and

friendships may range from simple, short term events,

such as saying hello in the

S4m I SAFAK

2/lift2

2

1 - 8

hallway or one student helping another find his or her way to the cafeteria or with a

homework assignment during study hall, to more complex, long-term relationships

where two or more students "hang out" together, socially interact, and freely help

and assist each other inside and outside of school. It should be noted that most

people agree that supportive relationships and friendships are highly

individualistic, fluid and dynamic, vary according to the chronological age or the

participants, and are largely based on free choice and personal preference. They

cannot be easily defined and programmed: and they certainly cannot be forced

(Perske & Perske, 1988). However, this does not mean that they cannot be facilitated

and encouraged by sensitive educators and parents (Stainback et al., 1989).

Proximity. Research has indicated that a critical variable in peer support and

friendship development is proximity (Asher & Gottman, 1981). That is, if a student

without friends is to gain the support and friendship of other students, he or she

must, at the very least, have the opportunity to be with other students. There are a

number of activities that can provide opportunities for a student lacking friends to

be with other students. One is to help the student needing friends become involved

in extracurricular activities of his or her choice in which other class members

participate, such as band, photography club, and/or pep rallies. Arranging peer

tutoring, buddy systems and cooperative learning can also be useful in providing

opportunities for an isolated student to get to know classmates.

Encourage support and friendship development. School personnel can

encourage students to build peer relationships with one another by involving

students in thinking about supportive relationships and friendships as part of the

curriculum. Some students may need specific instruction in identified social skills.

It is important to remember that this instruction will be most effective if it is

provided in the natural environments and activities where these skills are used

with their peers. Many teachers believe that social interactions and potential

friendships tend to develop among students who understand and respect each

others' differences and similarities (Stainback et al., 1989). One way to foster this

understanding in the classroom is to infuse information about individual

differences and similarities into existing reading materials; health and social studies

classes, and extracurricular activities such as assembly programs, plays, school

projects, service activities, and/or clubs.

Possibly the most important way to promote supports and friendships among

students is to be a good model. Teachers must communicate to students through

their behavior that every student is an important and worthwhile member of the

class. To be a good model, it is essential to indicate acceptance and positivity toward

all class members.

Adapted from:

Garbler, A., & Lipsky, D.K. (1990). Students as instructional agents. In W. Stainback & S. Stainback

(Eds.), Support networks for inclusive schooling. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Stainback, W. & Stainback, S. (1990). Fadlitating peer supports and friendships. In W. Stainback &

S. Stainback (Eds.), Support networks for inclusive schooling. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

See I; SAFMC

2/ISM2

1 - 9

(3)

SUPPORT FACILITATOR

While there are many individuals within a school who can provide support

to each other (e.g., teacher, specialists, aides, students), there is no

individual

responsible for facilitating supportive relationships and/or other supports that may

be needed. As the supportive roles are recognized and developed, there is a need for

personnel knowledgeable in the facilitation of supportive relationships to work

with regular classroom teachers and students to organize, coordinate, and promote

the variety of supports needed. This role could be assumed by former special

educators, consultant, supervisors, or other educators interested in assisting

classroom teachers to coordinate support networking. This individual is called the

integration specialist, special education teacher, resource specialist, special education

case manager, and support facilitator depending on

what state, city or district they

live in. The responsibilities vary almost as much as the names as this position is

developing to meet the needs of each individual student, school and district.

The support facilitator's role can be defined as carrying out a three step

process. The first step is identifying with regular classroom teachers

and students

the types of informal supportive relationships and/or professional supports they

would like to have. This includes discussing with and helping teachers and

students become aware of the various support options available. The second step is

collaborating with teachers and students in determining those supports they need in

their classroom. During these two steps, the support facilitator should listen to and

jointly identify with the teachers and students possible supports. The process of

jointly gathering information, defining the problem to be addressed and identifying

supports is fundamental to the third step, which is assisting in organizing and

implementing those supports deemed most likely to be appropriate or worthwhile.

It is important that teachers and students be inherently involved in the selection,

development, and implementation of the supports since ownership of the

support(s) by teachers and students is essential for a collaborative venture to work

(Conoley & Conoley, 1982; Idol-Maestas, Nevin, & Paolucci-Whitcomb, 1984;

Schowengerdt, Fine, & Poggo, 1976).

It should be noted that collaboration means

that the support facilitator, teacher, students, and other school personnel work

together cooperatively with no one assuming an expert, supervisory, or evaluator

role. At any given time any person may assume leadership or be the giver or

receiver of information. It depends on who has the expertise at the given time or in

a particular situation.

The skills needed by the support facilitator are similar to those skills needcd

by educational consultants, which include providing technical assistance,

coordinating programs, and communicating with other professional, parents, and

students (Goldstein & Sorcher, 1974). However, the difference between the slapport

facilitator and the educational consultant lies in the nature of the technical

assistance provided. The technical assistance provided by the educational

consultant is based on the premise that the educational consultant has acquired

mastery of the educational process (i.e., assessment, planning,

implementation, and

Sic 1; SAFAK 11

2/11/92

2.7

1 10

evaluation) appropriate for mainstream settings (Heron SE Harris, 1987; Idol et al.,

1986; Idol-Maestas, 1983; Rosenfield, 1987). The technical assistance provided by the

support facilitator is based on the premise that the support facilitator knows the

structure, how to implement, and the effectiveness of various support options, is

informed regarding the availability of support options, and is able to assist teachers

and students in selecting the most appropriate options for a given situation. The

educational consultant provides support to teachers and students to enhance the

instruction of students, while the support facilitator develops a network of supports

to enhance the educational success and friendships of students. One support in that

network may be the educational consultant.

The support facilitator needs a working knowledge of the support models and

resources available that can be utilized to facilitate support networks to provide

needed assistance in the mainstream. This involves an understanding of and how

to informally facilitate natural supportive relationships among students, teachers,

and others, as well as how to effectively use support models such as professional

peer collaboration and the student planning team process.

Assessing and matching the needs of students and teachers to applicable sup-

port options and resources available is another skill needed to carry out the job of a

support facilitator. To identify what assistance is required, the support facilitator

needs experience in and knowledge of regular classroom curriculum, methodology,

and programs and the ability to listen to what support regular classroom teachers

and students believe they n?ed to be successful. Once the needs of a teacher and/or

student are determined, a support facilitator needs to work collaboratively with the

classroom teacher and students to organize and operationalize those supports and

resources deemed necessary. The support facilitator may act as a mediator or catalyst

to promote communication and collaboration among those involved. They can be

involved in such tasks as locating specialists, team teaching, and/or helping with

the organization of assistance teams for teachers: and for students, they can be in-

volved in facilitating peer tutoring, friendship development, and cooperative learn-

ing activities and the development. As support facilitators, they can interweave a

network of varying supports into a comprehensive and coordinated support system.

Specific activities a support facilitator might do include:

1.

Facilitate the establishment and coordination of a School Site Integration

Task Force.

2. Establish a peer support committee

the peer support committee is

classroom-based and usually made up of four to six students who work on

ways of making the classroom a supportive, accommodating, positive

learning environment to help all class members experience success, rather

than determining how to solve a problem or difficulty for a particular

student. The committee often becomes involved in organizing and

participating in buddy systems, peer helpers, study partners, and "circles of

friends" within a classroom.

3.

Individual Student Planning Teams are made up of individuals who are

involved with a student with disabilities on a regular basis. A major focus

Sec I; SAFAK

9

2/11192

t

of the team is to assist and provide support to a classroom teacher and or

student. The support facilitator participates on this team and may be

responsible for organizing and initial facilitation of the team.

4.

Serving as a Team Teacher the support facilitator can teach in his or her

curricular expertise area (e.g. learning/strategies and/or community based

instruction) or simply assist the classroom teacher in an area where the

classroom teacher has the major expertise. The support facilitator can also

foster or enable cooperative or team teaching activities to occur among a

variety of teachers in a school by freeing one teacher to team with another

classroom teacher, thereby capitalizing on the expertise of colleagues within

a school in a teaming capacity.

5.

The support facilitator can serve as a curriculum analyst by breaking down

curriculum into different levels to meet individual student needs and/or

adding components or making adaptations to lessons which enable greater

participation of students at different levels.

6.

The support facilitator may locate specialists who are needed in an

integrated classroom to address some difficult or complex educational needs

or situations that a student or teacher might encounter. In addition, she

may assist with communication and coordination between the specialist

and the teacher and/or help organize a student's daily schedule to include

time for instruction in a specialty area such as braille, mobility, etc.

7.

Coordination between the school and the home is often critical to the

quality of eduction that can be provided any student. A support facilitator

can be instrumental in arranging for sharing of informatiun between the

home and the school. In addition, the support facilitator may provide

support to parents in finding ways they can help their child(ren) operate

effectively in the mainstream of school and community activities.

8.

The support facilitator can be instrumental in locating materials and

equipment needed by various teachers to address the diverse needs of their

class members.

While it is true that many schools do not have all the resources they need,

there are usually an array of financial, equipment and people resources available.

There are also many teachers with expertise in a variety of areas, as well

as the

students themselves, volunteers, parents, counselors, and administrators. The job

of the support facilitator is to help organize and coordinate all of these different

resources into a comprehensive support network for teachers and students in the

mainstream.

Adapted from:

Stainback, W. & Stainback, S. (1990). The support facilitator at work. In W. Stainback and S.

Stainback (Eds.), Support networks for inclusive schooling. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Stainback S. & Stainback W. (1990). Facilitating support networks. In W. Stainback and S. Stainback

(Eds.);Support networks for inclusive schooling. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Socl;SAFAKfl

2/11/92

2 7

"My child is not

a

salmon. She

can't swim upstream... She can't

get up your cascade... if she

tries, she'll drown."

Sec 1; SAFAK

2/11)92

2

Parent of a 5-year old;

In response to special education

placement for her daughter

on the continuum of services.

1 - 13

(4)

STUDENT INSTRUCTIONAL PLANNING TEAM

The purpose of an Instructional Planning Team is to enable general and

special education staff to work together to plan and implement comprehensive

instruction for students with special needs in typical school and community

environments.

The make-up of the team will depend on the student's needs but typically

includes special and general educators, parents, sometimes the student, classmates,

and other key individuals who provide support to the student. Other key

individuals may include vocational specialist, therapists, school principal, etc.

It is

practical to establish a core team which meets and plans together on a regular basis

and invites other support individuals to participate as needed. However, all

individuals who support the student need to come together periodically to share the

vision for the student, share success, monitor progress, re-evaluate and modify

program as necessary and plan for transition.

The presence of the student at meetings serves as a constant reminder that

the ability and willingness of the team to problem solve creatively and collaborate

will impact the quality of a person's life and that the meeting of a team is not simply

an academic exercise. Involvement of family members can assist in achieving

continuity of programming over time. Educational priorities identified by family

members should receive primary consideration. The classroom teacher has several

primary functions including: 1) to view the individual as a member of the class

rather than a visitor; 2) to contribute information about the classroom curriculum,

instructional strategies, management techniques, routines, and rules; 3) to work

collaboratively with the other team members in developing the educational

program and in including the individual with his or her peers in typical classroom

activities and routines; and 4) to provide a model of appropriate interaction and

communication with the student, including recognition and acknowledgement of

the positive attributes and contributions of the individual. The special education

teacher/support facilitator with training in curricular and instructional adaptations

and related services personnel with training in specific functioning areas (e.g.

motor, vision, hearing) assume primary responsibility for adapting curriculum,

materials, equipment, or instructional strategies such that the educational needs of

the student can be met in the context of typical school and community

environment. Support from personnel with specialized training could range from

primarily consultation with the classroom teacher to a combination of consultation

and direct intervention with the student and classroom activities.

If the team

decides that direct instruction by a professional support person is necessary, in most

situations that instruction should occur in regular class settings and other typical

school and community environments. Some students with high needs require, at

least initially, an instructional assistant to be present in the regular class. If this is

the case, the instructional assistant must collaborate as a team member. Classmates

are the experts on formal and informal demands and opportunities of regular

school life. They play a key role in supporting one another. As contributing

See 1; SAFAK

fl

VI SA2

2::

1 - 14

members of individual student planning teams, classmates provide the evidence

that students with high needs can be accepted, valued and contributing members

of

the school community. A critical role of the building principal is to demonstrate

support of collaborative teaming by setting an expectation

that teachers will

collaborate, providing incentives for collaboration, promoting training on efficient

team planning, and arranging for the time necessary to

plan.

The student planning team works to identify strategies for integrating IEP

goals into general classroom, integrated community and work activities.

Team

responsibilities include:

1.

Identifying current and future integrated school and community

environments in which student participation is desired.

2.

Specific goals and objectives which target behaviors for instructional

emphasis within activities in each environment are generated by the team.

3.

The team then develops individualized supports and adaptations to ensure

success therein.

The challenges presented by these students have led to creative solutions and

the development of a planning and decision-making process for meeting IEP goals

in integrated activities and environments.

Essential for effective team work is recognition that quality integration requires

ongoing team problem-solving. Teams must meet on a regular basis. No one

individual is solely responsible, the team shares in solving problems as well as

celebrating success.

The successful operation of the team depends on the skillful use of the

essential components of cooperative group structure (i.e., face-to-face interactions,

individual accountability, positive interactions, individual accountability, positive

interdependence, and individual and small group interpersonal skills).

Responsibilities are assumed based on interest and skills of team members and may

be permanent or rotated. Other responsibilities which are important include the

following:

1.

Planning, providing and evaluating specialized instruction in all

educational settings.

2.

Planning for merging special education and general education services.

3.

Monitoring student progress on IEP goals.

4.

Scheduling and coordinating information between consultants, related

service providers, and all other educational team members.

5.

Ensuring positive communication with parents.

6.

Ensuring that others in the student's environments learn to interact with

the student.

7.

Ensuring that all persons who will provide direct instruction to the student

are adequately trained.

Scheduling a regular time seems to work best so team members can plan for

the meeting. Meetings are essential for colleagues to creatively plan and problem

solve tor;ether, to share and learn from each other, and to collaboratively respond to

each student's needs. Scheduling more often and for longer meetings may be

Sec I; SAFAK

II

VI 8/92

1 15

needed at first until the team becomes comfortable and efficient with the process.

There are several strategies for making planning time available, such as, team

teaching to cover classes, rotating substitutes, excusing regular education teachers

with special education responsibilities from duties, and including regular planning

time into the general school schedule for all staff. Meetings will take less time and

be more productive if a specific agenda is planned, leadership roles are distributed to

ensure efficiency and meeting minutes are taken.

Adapted from:

York, J., & Vandercook, T. (1989). Strategies for achieving an integrated education for middle school

learners with severe disabilities. In J. York, T. Vandercook, C. MacDonald, & S. Wolf (Eds.),

Strategies for full inclusion. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Institute on

Community Integration.

Vandercook, T., & York, J. (1990). A team approach to program development and support. In W.

Stainback & S. Stainback (Eds.), Support networks for full inclusion. Baltimore: Paul H.

Brookes.

3 1.

See i; SAFAK II

2/11i/92

(5)

MAPS:

THE McGILL ACTION

PLANNING SYSTEM

A planning process used to facilitate

full participation for children with

challenging educational needs

3:2

Sec 1; SAFAK fl

211102

1 - 17

INTEGRATED EDUCATION: MAPS to Get You There

Terri Vandercook and Jennifer York

The McGill Action Planning System (Maps) (Forest, Snow, & Lusthaus, in

press) is a positive and affirming process that assists a team of adults and children to

creatively dream and plan, producing results that will further the inclusion of

individual children with labels into the activities, routines, and environments, of

their same age peers in :heir school community. The principles underlying and

guiding the process include: (1) integration, (2) individualization, (3) teamwork and

collaboration, and (4) flexibility.

The MAPS planning typically occurs in one or two sessions. Participants are

arranged in a half circle, with the facilitator positioned at the open end of the circle.

The information and ideas generated during the process are recorded on large chart

paper which serves as a communication check during the session and as a

permanent record when the planning is finished. The role of the facilitator is to

elicit participation of all team members in the collective design of an integrated

school and community life for the individual student.

The following are the seven questions which comprise the MAPS process:

(1)

What is the individual's history?

Aside from the individual for whom the planning is occurring, family

members are the most important members of the circle because they typically know

the individual better than anyone else. Because of this, family members, and the

individual to the greatest extent possible, are asked to spend a few minutes talking

about the individual's life history, including some of the milestones.

(2)

What is your dream for the individual?

This question i

intended to get people to develop a vision for the

individual's future, to consider what they want for that person, and to look beyond

the current reality. Those dreams can become reality if there is a common

commitment to strive for them. The dream question forces team members to

identify the direction they are heading with the individual; only then can specific

plans to be made for realizing the vision. This is not to say, however, that the

vision, plans, or expectations are set in concrete; they will be challenged continually

as more is learned about how to facilitate inclusion in the school community and as

positive outcomes are realized. Depending upon the age of the individual, it may be

difficult to dream for them as an adult; if that is a problem, team members can be

encouraged to think just a few years ahead.

(3)

What is your nightmare?

This is a very difficult question to ask the parents of any child, yet an

extremely important one. The nightmare presents the situation that the members

of the individual's team and others who care for him or her must work very hard to

keep from happening. Parents frequently relate the nightmare as a vision of their

child being alone.

See 1; SAFAK U

2/111/42

3 :-;

1 18

(4)

Who is the individual?

Everyone in the circle participates in responding to this question. The

participants are asked to think of words that describe the individual, i.e., what comes

to mind when they think of the person? There are no right or wrong words.

Participants take turns going around the circle until all thoughts have been

expressed. Participants can pass if nothing comes to mind when it is their turn to

supply a descriptor. When the list is complete, the facilitator asks certain people,

usually family and peers, to identify the three words from the list that they feel best

describe the individual.

(5) What are the individual's strengths, gifts, and abilities?

So often when educational teams get together, they dwell upon the things

that the individual cannot do as opposed to identifying and building upon the

strengths and abilities of the individual. The facilitator asks the participants to

review the list which described the individual as a way to identify some of his or her

strengths and unique gifts. In addition, they are instructed to think about what the

individual can do, what he or she likes to do, and what he or she does well.

(6) What are the individual's needs?

This question provides an opportunity for all the team members to identify

needs from each of their unique perspectives. When the list of needs is complete,

family, friends, and educators are asked to prioritize the identified needs. The list of

assets and the identified needs are a primary basis for design of the educational

program

(7) What would the individual's ideal day at school look like and what must be

dome to make it happen?

Because MAPS is a process to assist teams to plan for the full integration of

students with high needs into regular, age-appropriate classes, frequently attention

to this question begins by outlining a school day for same-age peers who do not have

labels. Next, the team begins to strategize ways that the needs identified in the

previous question can be met in the context of the regular education day. Finally,

initial planning occurs for the supports needed to achieve successful integration. As

learners reach middle and high school age, the ideal school day will include

instruction in both regular education and a variety of community instruction sites

(e.g., home, worksites, stores, and recreation places).

The MAPS process provides a common vision and road map for all team

members, enabling them to be supportive and effective in furthering the integration

of learners with disabilities into regular school and community life.

Sec I; SAFAK

21111/92

3

EVERYONE

BELONGS

Marsha Forest

and

Evelyn Lusthaus

The movement to educate

all children

even students labeled as

severely or

multiply handicappedin

ordinary

classrooms with their brothers

and

sisters, friends and

neighbors, has

caught the imagination of parents

and

educators across Canada.

This momentum is founded on a

simple, yet profound

philosophy: Ete-

ryone belongs. In a system

in which

each belongs, the homeroom

for all

children is the ordinary classroom.

Every child's education

begins with

placement in a regular classroom,

with

the necessary support

services pro-

vided to the child and the regular

class

teacher. With this system, the use

of

special, self-contained

classrooms is

almost extinct. In the Waterloo

Region

Separate School Board, for

example,

which has a student population

of

approximately 20,000, very few chil-

dren are served in

self-contained

classes. All the other children

with

special needs are learning

alongside

their age peers in ordinary

classrooms.

In this article, a case study

illus-

trates how this system

works and

introduces MAPS, a planning process

used to facilitate full participation

for

I.

MIK

children with challenging

educational

needs.

Carla Comes to School

In the spring of 1986, Danny

and

Sandra Barabadora and their daughter

1

19

Carla came to their local school to

register Carla for seventh grade. Carla

was labeled severely mentally re-

tarded, but her parents were request-

ing their local school to permit Carla

to attend class with other children

her

age beginning the following

Septem-

ber. The school board was the Hamil-

ton-Went worth Separate School

Board.

The principal welcomed the family

enthusiastically and told them how

excited he was to have Carla in the

school. He also admitted that he and

his staff had a certain amount of

anxiety about having a child with such

challenging rkeeds entering a regular

seventh-grade class and that they

wanted to do their best. They had

previously integrated other children

with special needs, but none whose

needs were as challenging as Carla's

appeared to be.

A meeting was set before the end

of the spring semester to sit down and

chat about the overall expectations for

Carla's schooling. The principal, re-

ceiving home room teacher, and

Carla's parents were there. The princi-

pal asked about the parents' expecta-

tions, explained the school program

in general, and provided an overall

picture of how Carla could fit in.

Just before school began in the fall,

another short meeting was held with

the principal, receiving teacher, and

parents together with a team of other

people who could be helpful. Because

Carla had a mental handicap, a special

education resource person was pre-

sent; because her language was very

limited, the speech and language re-

source people were there; because

she

waS being integrated into the school.

an outside consultant was

invited to

assist in the planning process.

Everyone agreed that the teacher.

the other students, and Carla

all

needed to get to know one another for

2 weeks before any specific planning

would take place. It was decided thai

Carla would follow the regular seventh.

grade school day and the teacher

would get to know her without an

educational assistant present. At the

end of the 2 weeks, anothcr team

meeting would be held.

On the first day, the teacher wa

exhausted and tense, but by the thin%

day, he mentioned that he wa:

"amazed at how much Carla coulJ

4.1

MAIL_

Nips

Okbait

-*N,

t5-

do- and that he was getting to know

her very well, particularly because the

assistant wasn't there. Could he han-

dle it for 2 weeks? Yes, as long as the

team got together again after the 2

weeks.

During that time, the consultant

approached Carla's class of peers to

begin to build a "friendship circle"

around her. This involved speaking

honestly and directly to the students

about why Carla was being integrated

and what the students could do to be

involved in the process. The consult-

ant asked for volunteers to form a

friendship circle around Carla, and the

teacher selected 4 main actors from the

19 students who volunteered. A tele-

phone committee was formed so that

Carla would get one telephone call

each evening from one of her new

classmates. Carla had never before

received her own phone call, but

iv Al C' o

I 0 0

Npersft

Through MAPS

(Map Action Plan-

ning System) chadren

with challenging ex-

ceptional needs add

to the quality of edu-

cation for everybody.

despite her limited language, she was

able to communicate with her new

friends.

MAPS: An Action

Planning System

The team meeting was the beginning

of a formal planning process for Carla's

school program. The process they

followed was based on a planning

svstem developed at McGill University

(@orest, Snow, 1987) called MAPS

(Map Action Planning System). MAPS

is a systems approach designed to help

team members plan for the integration

of students with challenging needs

into regular age-appropriate class-

rooms. Members of the MAPS plan-

ning team for Carla included the

exishng planning team as well as her

'4*

;.-

t

brothers and many of her new friends

at school.

A unique feature of the MAPS

planning team is the inclusion of

children in the planning process. As

the principal of Carla's school said, "If

I hadn't seen it with my own eyes, I

wouldn't have believed it." He was

referring to the influence and power

of student participation in the plan-

ning process. The inclusion of stu-

dents is a key element in the MAPS

process, for students are often the

most underutilized resource in schools.

The point of the planning process is

to come up ivith a plan that makes

good sense for the youngster with

challenging needs. In our experience,

students often understand this far

better than adults, and without their

presence on the team the results

would not be as good.

BEST COPY-AVAlLABLE

The meeting opened with a

review

of the events to date.

Over all, it had

been a good 2 weeks.

The teacher, the

class, and Carla had

become ac-

quainted with one another.

Now it

was time to focus on

the seven key

questions that are at the

heart of the

MAPS planning process.

What Is Carla's History?

This questioh is meant to

give all team

members a picture of what

has hap-

pened in the student's life.

Parents are

asked to summarize the

key mile-

stones that have

affected their child's

life and schooling. For

example. one

key milestone in Carla's

life was that

she had been critically ill

for about a

year, hospitalized,

and not expected

to live. Someone

from the family was

with her day and night for over a year.

which affected Carla's ability to

be

without her mother once

she went

back to school.

What Is Your Dream

for Carla?

Parents of children with

handicaps

have often lost their ability

to dream;

they have not had the

opportunity to

think about what they want most

for

their children. This question

restores

the chance to have a vision

based on

what they really want,

rather than

what they think they can get.

With

this question, we tell parents:

"State

your dream. What

vision do you have

for your child in the future?

Don't hold

back. Say what you've never

dared to

say before. Forget

reality for a while

and dream.'

Sometimes this is the first time

professionals have ever had the oppor-

tunity to hear what parents

hold in

their hearts and minds for

their chil-

dren's future. It is important to

listen.

Caria's parents said they dreamed

that

Carla would be able to go to

high

school with her brothers, get a

job, and

one day live with some

friends in the

community.

What Is Your Nightmare?

The nightmare makes explicit

what is

in the heart of virtually every

parent

of a child with a handicap.

Caria's

parents said. "We're afraid

Cada will

end up in an institution,

work in a

sheltered workshop, and have no ont

wt. .446 "

Who Is Carla?

The next question, "Who is Carla?",

was meant to begin a

general brain-

storming session on Carla's character-

istics, no holds barred. We went

around the circle and asked everyone

to state characteristics until all

thoughts

were exhausted. Examples

of the re-

sponses to Carla's

"Who" question

follow.

Is 12 years old.

Is happy and smiling.

Has two brothers.

Lives with mom and dad.

Is lively.

Loves touch and warmth.

Pulls her hair.

Is playful.

Is temperamental.

Is Lnquisitive.

Has a real personality.

Is small.

Has a good memory.

Is fun to be with.

Wants to be involved.

Uses some words.

The facilitator asked the parents to

circle the three words they felt best

described Carla. Her mother circled

"happy," "temperamental," and "real

personality," while her father circled

"aware," "memory," and "small."

One of the teachers circled "tempera-

mental," "small," and "memory." The

students circled "personality,"

"small," and "lively." The rule fol-

lowed was "NOlargon, no labels; just

describe how you see the person." The

result was that the image of a unique

and distinct personality emerged.

What Are Carla's Strengths,

Gifts, and Talents?

This is a vital question, for all too often

we focus on what a person's

weak

areas are. Many parents

have prob-

lems with this because they have been

focusing on negatives for so long. This

question turns their focus to the

positives. Carla's planning group re-

sponded as follows.

She's a real personality.

She's persistent.

She has a good memory.

She's inquisitive.

She loves people.

She's daring.

She's a good communicator.

She loves music.

She can follow directions.

She eats by herself.

`.4 "

1

21

She dresses and undresses herself.

She can turn on the VCR and use

the tape recorder on her own.

She washes her hands and brushes

her teeth.

What Are Carla's Needs?

This question is very important. Needs

vary according to who is

defining

them, so Carla's group was divided to

get a variety of points of view. Their

answers to the question follow.

According to her parents:

Carla needs a communication sys-

tem.

She needs a way to express feelings

and emotions.

She needs to be independent.

She needs self-motivation in starting

things she presently cannot do.

She needs to stop pulling her hair.

She needs friends at home and at

school.

According to her peers:

She needs to be with her own age

group.

She needs to feel like one of the

group.

She needs to wear teenage clothes.

She needs goop on her hair.

She needs to have her ears pierced.

She needs a boyfriend.

The teachers were in agreement with

the parents on what Carla's needs

were, but they added that she needs

to fit in and be part of the group.

At the dose of this exercise, four

main needs were summarized: Carla

needs friends at home and at school;

she needs a communication system;

she needs to learn to be more inde-

pendent; and she needs to stop pulling

her hair.

Carla's Ideal Day

To many, Carla would be defined as a

severely to profoundly mentally handi-

capped student who should be segre-

gated in a school or class for retarded

students. To her receiving school, she

was a spunky 12-year-old who

should

be attending seventh grade with her

peers. The school had all the

right

ingredient= a cooperative family, a

wekoming and cooperative school prin-

dpal, a nervous but inviting teacher,

and V' seventh-grade students.

Thus, with a team approach, the

idea that they did not have all the

answers, and a spirit of adventure. the

*A.v.

team started to create a plan. The

teacher indicated that his main need

was for an educational assistant at

various times of the day and a program

created by the special education re-

source people.

Now the team was ready to go step

by step through the day and deter-

mine activities, goals, objectives, and

environments. In many educational

planning processes, goals and objec-

tives stand outside the rhythm of the

school day; they should, however, flow

.

from the environment and be inter-

twined with the daily schedule and

rhythm of the classroom. The goals

and objectives for Carla were arranged

around the following schedule:

8:40-8:45 a.m. The day begins. Carla

arrives in a taxi and is met by Susie and

some other children. Who is responsi-

ble for getting Carla from the taxi to

the classroom? Volunteer: Susie.

8:45-8:55. Opening exercises. Carla

will sit at her desk in the middle of the

second row, sing "0, Canada," and

participate in the beginning of the day.

8:55-9:30. Language arts period.

Does it make sense for Carla to follow

the seventh-grade program? Does it

meet her needs? No. Can it be modi-

fied? No. Should she have her own

program in the language and commu-

nication area? Yes. Where should this

take place? In the room, at the side

table where other students do indi-

vidualized work. The educational as-

/ sistartt will carry out a program de-

signed ty the special education re-

source team to improve Carla's func-

tional reading, writing, and speaking.

9:30-9:50. French. After much dis-

cussion, the team agreed that Carla

enjoys French and that the French

teacher welcomes her, but she should

not stay for the whole period. She will

stay 20 minutes for the conversational

French portion of the class, songs,

weather, and so forth. She will listen.

learn to recognize French, and learn a

few words. She can learn numbers and

colors and point to some pictures in

French. Carla's homeroom teacher and

the French teacher will design this

curriculum with the assistance of the

special education resource person. No

educational assistant is needed in this

time slot.

9:50-10:10. Individualized computer

program work. Carla will work on the

computer with the educational assis-

tant or by herself in the homeroom

classroom where everyone else uses

the computer. Programs will be devel-

oped in cooperation with the school

district communications team.

10:10-10:25. Recess. Carla will get

ready to go out with a volunteer circle

of friends. They will make sure that

she is not trampled.

10:30-11:00. The seventh-grade

class has either French or communica-

tions. At this time a creative communi-

cation progrim developed by district

personnel I's being put in place for

Carla. For example, one goal is learn-

ing to dial and talk on the telephone.

The school principal has volunteered

both his office and his telephone (no

long distance calls).

11:00-11:20.

Silent reading. Carla

will choose library books and do silent

reading along with her classmates.

No extra help is needed other than

that from peers.

11:20-11:50. Religion. Carla will

have a modified program designed by

her homeroom teacher and the special

education resource teacher. No extra

assistance is needed except for what

other children offer. She will have

tasks to complete along with the other