United

States

~nera[

Accoun4in~

~f14ce

~

~,5~

I4

'Testimony

Before

the

Committee

on

Banking,

Housing,

and

Urban

Affairs

United

States

Senate

~~

°"

D~'i"pry

Il

~1

~

U]~AN~E

10:00

a.m.,

EST

~~„

`

~~~~

o

~

145965

Tuesday

`

•W

February

1

B,

1992

The

Failures

of

Four

Large

Life

Insurers

Statement

of

Richard

L.

Fogel,

Assistant

Comptroller

General,

General

Government

Programs

GAOIT-GGD-92-13

cao

Foy

i6o

~i2rn)

as

~~

1

~

w

s~~~

o~:o~~~

_

_

..

_

-_

_

_

_

_~

,s

~-

-

_

•_

-

s-

-

_

SUMMARY

OF

STATEMENT

BY'

Richard

L.

Fogel

Assistant

Comptroller

General

General

Government

Programs

GAO

is

testifying

on

the

financial

characteristics

and

regulation

of

four

large

insurance

companies

recently

taken

over

by

state

regulators.

GAO's

observations

about

the

regulation

of

the

insurers

are

preliminary

because

its

review

of

the

performance

of

state

regulators

is

not

yet

complete.

Executive

Life

and

its

subsidiary

xecutive

Life

of

Net~t..Ynrk

were

taken

over

in

April

1991

by

state

reguS8t7Srs

in

CaYifornia

and

New

York,

respectively.

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers

were

taken

over

in

May

1991

by~~California

and

Virgint~t'~""~e~pectively.

These

failures,

due

in

large

part

to

a

reckless

strategy

of

high

growth

and

investment

in

high

-risk

assets,

hive

had

national

consequences.

The

four

insurers

had

a

total'of

more

than

900,000

policies

with

policyholders

and

annuitants

in

every

state.

During

the

1980s,

the

assets

of

the

four

insurers

grew

sit

to

ten

times

faster

than

assets

of

the

life

insurance~~

,

industry

overall.

This

growth

was

fueled

primarily

by

sales

of

high

-yield

retirement

investment

products,

not

traditional

life

insurance

policies.

To

cover

the

high

rates

paid

to

policyholders

and

maintain

profitability,

the

insurers

invested

heavily

in

high

-

risk

assets

--most

notably

junk

bonds.

High

upfront

costs

due

to

rapid

growth

seriously

depleted

the

insurers'

surplus,

or

riet

worth.

To

bolster

their

statutory

surplus

gnd

reported

financial

condition,

the

four

insurers

reduced

policy

reserves

on

their

balance

sheets

through

reinsurance

transactions

ar~d

received

from

their

parent

holding

companies

millions

of

dollars

in

surplus

infusions

and

loans.

Although

reinsurance

fs~8

legitimate

practice

in

the

life

insurance

industry

to

reduce

the

strain

on

surplus

of

selling

new

policies,

the

Executive

Life

insurers

and

First

Capital

relied

on

questionable

reinsurance

transactions

to

artificially

inflate

their

surplus.

Without

reinsurance

and

borrowed

surplus,

the

Executive

Life

insurers

would

have

been

insolvent

as

early

as

1983.

Dwindling

surplus

due

to

rapid

growth

together

with

massive

junk

bond

holdings

of

the

four

insurers

led

to

a

loss

of

policyholder

confidence,

subsequent

policyholder

runs,

and

eventual

state

takeovers

of

the

companies.

California

and

New

York

regulators

of

the

Executive

life

insurers

recognized

before

the

takeovers

that

the

insures

had

serious

solvency

problems,

and

California

and

Virginia

regulators

recognized

that

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Hankers,

respectively,

were

undercapitalized.

However,

the

regulators'

oversight

of

the

insurers

was

not

effective

in

stemneing

their

financial

deterioration.

although

GAO

hay

not

yet

determined

the

full

extent

o~

inadequacies

in

state

handling

of

these

in~urera,

it

has

observed

significant

weaknesses

in

the

regulatory

oversight

of

the

four

insurers.

State

insurance

regulators

lacked

timely,

complete,

and

accurate

information

needed

to

effectively

monitor

the

four

troubled

insurers.

Regulators

did

not

get

financial

data

early

enough

to

identify

and

react

to

the

insurers'

problems.

Moreover,

the

statutory

financial

statements

did

not

fairly

reflect

the

insurers'

true

conditions.

Even

though

regulators

were

aware

that

the

Executive

Life

insure=s

and

First

Capital

had

serious

solvency

problems,

they

examined

the

insurers

only

once

every

3

years.

Regulators'

efforts

to

limit

junk

bond

holdings

and

restrict

unacceptable

reinsurance

were

not

effective

in

stemming

the

solvency

problems

of

the

four

insurers.

Regulators

did

not

know

about

the

quality

Dr

value

of

the

insurers'

junk

bond

holdings

and

did

not

have

specific

authority

to

limit

such

holdings

when

the

insurers

built

up

their

portfolios.

Even

when

New

York

and

California

acted

to

limit

more

dunk

bond

acquisitions

by

the

insurexs,

these

limits

did

not

reduce

the

insurers'

exposure

to

mounting

junk

bond

losses.

Whereas

New

York

took

forceful

--

albeit

lade

--action

to

eliminate

reinsurance

problems

at

Executive

Life

of

New

York,

California

practiced

regulatory

forbearance

for

•Executive

Life

and

First

Capital.

Finally,

holding

companies

are

a

regulatory

blind

spot.

State

holding

company

laws

rely

an

insurer

disclosure

to

monitor

affiliated

relationships,

and

some

states

require

prior

regulatory

approval

to

prevent

abusive

transactions.

Except

for

infrequent

field

examinations,

regulators

have

no

way

to

verify

insurer

-reported

information.

GAO

does

not

know

to

what

extent

interaffiliate

dealings

may

have

contributed

to

the

failures

of

the

four

insurers

in

part

because

regulatory

examination

reports

from

New

York

and

Virginia

are

nod

yet

available.

However,

on

the

basis

of

preliminary

work

in

California,

GAO

found

that

Executive

Life's

failure

to

comply

with

state

holding

company

laws

undermined

California

regulators'

efforts

at

solvency

monitoring.

Mr.

Chairman

and

Members

of

the

Committee:

We

are

pleased

to

be

here

today

to

diacus~

the

financial

characteristics

of

four

large

insurance~compaaies

that

were

taken

over

by

state

regulators

and

our

preliminary

assessment

of

the

regulatory

actions

rege~ding

those

insurers.

Today,

I

will

provide

you

with

a

picture

of

the

companies'

financial

condition

leading

up

to

their

failures

and

our

observations

thus

far

about

the

performance

of

the

state

regulators

as

they

supervised

the

four

insurers.

Exac.utiv9._Life

and

its

subsidiary

Executive

Life

of

New

York

--

both

owned

b

First

F.

~r»t-i

~~~""

'~"""

y

,,,.,..~,

ue..,

~arparaton-=were

taken

over

i'n

April

1991

by

state

regulators

in

C~li,fornia

and

New

~~ar~C,.

~.:.

respectively.

Fir$,~,Ca~tal

.

and,Fidelity

Bankers

--subsidiaries

of

First

Capital

Holdings,,.Corporation--were

taken

oVer~.~,n

May

1991

?~y

C~Y'ii`~o~Crita

and

Virginia,

respectively.

In

'egch

caae~

state

regulators

took

these

actions

to

stop

policyholder

runs

and

protect

the

insurer's

assets.

These

insurer

failures

have

had

national

consequences.

When

they

were

taken

over,

the

four

insurers

had

a

total

of

nearly

$85

billion

in

business

and

more

than

900,000

policies

with

policyholders

and

annuitants

in

every

state.

As

a

result

of

certain

moratoria

imposed

when

the

states

took

over

the

insurance

companies,

policyholders

concerned

about

the

Security

of

their

savings

have

been

unable

to

cash

in

their

policies.

Moreover,

the

-75,040

annuitants

of

Executive

Life

have

been

paid

only

70

percent

of

their

benefits.

Dw~.ndling

surplus

due

to

rapid

growth

together

with

massive

junk

bond

holdings

of

the

four

insurers

led

to

a

loss

of

policyholder

confidence,

subsequent

policyholder

runs,

and

eventual

regulatory

takeovers

of

the

companies.

Despite

untimely,

incomplete,

and

inaccurate

information,

California

and

New

York

regulators

of

the

Executive

Life

insurers

recognized

before

the

takeovers

that

the

insurers

had

serious

solvency

problems.

California

and

Virginia

regulators

recognized

that

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers,

respectively,

were

undercapitalized.

Th,e

regulators'

actions

clearly

were

not

effective

in

stemming

the

financial

deterioration

of

the

companies.

However,

we

have

not

yet

determined

the

full

extent

of

inadequacies

in

state

regulatory

handling

of

these

troubled

insurexs.

We

obtained

financial

information

about

the

four

insurers

from

annual

statutory

financial

statements

filed

with

state

regulators,

10-K

statements

filed

b~y

their

garent

holding

companies

with

the

Securities

and

Exchange

Commission,

public

reports

of

regulatory

financial

examinations,

and

analyses

done

by

insurance

rating

services.

To

identify

what

actions

were

taken

by

state

regulators

and

the

National

Association

of

Insurance

CQmmissioner~

~,NAIC

),

,

we

d'i'd"

`f

i"e~'dwork'

a~t

the

Californ~.a

Department

of

Insurance,

and

we

met

with

regulators

in

Virginia.

We

also

reviewed

records

of

recent

congressional

hearings

about

these

failures.

I

went

to

~mphasi~e

that

California,

New

York,

and

Virginia

were

cooperative

in

our

Current

review.

However,

we

do

not

have

statutory

access

to

state

insurance

departments

or

NAIC.

This

lack

of

access

had

on

several

occasions

limited

our

ability

to

assess

the

effectiveness

of

state

insurance

regulation.

BACK~AOUND

During

the

late

1970s

and

1980s,

investment

strategies

in

the

life

insurance

industry

changed,

and

profit

margins

dropped

due

to

increasing

competition

from

mutual

funds,

savings

and

~,oans,

and

other

financial

institutions

that

offered,investment

products

at

comparatively

higher

rates

of

return.

Before

the

late

1970s,

life

insurance

companies

focused

on

bearing

risks

of

death

and

illness

and

sold

products

offering

a

relatively

low

but

stable

return

for

policyholde=s.

In

response

to

increasing

competition

for

policyholders'

savings,

insurers

began

issuing

new

interest-

~ensitive

products

such

as

universal

li€e,

single

-premium

annuities,

and

guaranteed

investment

contracts

(GICs).

The

increasing

emphasis

on

selling

investments

had

significant

financial

effects.

The

higher

rates

of

return

insurers

offered

to

be

competitive

substantially

narrowed

their

profit

margins.

Also,

in

an

attempt

to

pay

these

higher

rates

and

maintain

profits,

some

insurers

--including

the

ones

we

are

discussing

today

--invested

heavily

in

high

-risk,

high

-.return

assets

such

as

noninvestment

grade

bonds

(junk

bonds)

or

speculative

commercial

mortgages

and

real

estate.

Competitive

strategies

like

these

have

strained

many

insurers

and

increased

the

number

of

insurer

insolvencies.

The

number

of

life/health

insolvencies

averaged

about

five

per

year

from

1975

to

1983.

Since

that

time,

the

average

number

more

than

tripled

to

almost

18

per

year,

with

a

high

of

47

in

1989.

Insurance

companies

are

subject

to

solvency

monitoring

in

each

state

in

which

they

are

licensed

to

do

business.

Once

regulators

identify

a

troubled

insurer,

they

must

be

able

and

willing

to

take

timely

and

effective

actions

to

resolve

problems

that

would

otherwise

result

in

insolvency.

When

problems

cannot

be

resolved,

regulators

must

be

willing

and

able

to

close

failed

insurers

in

time

to

protect

policyholders

and

reduce

costs

to

state

guaranty

funds.

The

insurance

department

of

the

state

in

which

the

company

is

domiciled

has

primary

responsibility

for

taking

action

against

a

financially

troubled

insurer.

State

regulators

do

not

regulate

insurers'

parent

holding

companies

or

noninsurance

affiliates

and

subsidiaries

of

insurers.

Instead,

most

states

have

various

statutory

guidelines

for

transactions

between~an

insurer

and

affiliated

companies,

and

some

states

require

prior

regulatory

approval

for

significant

interaffiliate

transactions.

2

r

Executive

Life,

Executive

Life

of

New

York,

First

Capital,

and

Fidelity

Sackers

shared

characteristics

worth

noting:

rapid

growth,

a

concentration

of

risky

assets,

and

dwindling

policyholders'

surplus,

or

net

worth.

These

insurers,

to

bolster

their

statutory

surplus

and

reported

financial

condition,

reduced

their

required

policy

re$erva~

through

reinsurance

transactions

and

received

from

their

parent

holding

companies

surplus

infusions

and

loans.

Such

a

strategy

can

significantly

effect

the

appearance

of

financial

strength

as

reflected

in

an

insurer's

financial

statements.

Without

reinsurance

and

borrowed

surplus,

the

Executive

Life

insurers

would

have

been

insolvent

as

early

as

1983.

Rapid

Growth

The

growth

in

assets

of

the

four

insurers

during

the

1980s

dramatically

outpaced

the

overall

asset

growth

of

the

life

insurance

industry.

While

assets

industrywide

nearly

tripled

in

the

last

decade,

rising

from

$481

billion

to

$1.4

trillion,

assets

of

the

four

failed

insurers

grew

at

six

to

ten

times

the

industry

average,

as

shown

in

Table

1.

Table

1:

Percentage

Growth

in

Reported

Assets

For

the

Life

Insurance

Industry

and

the

Four

Companies

(1980-1990)

Period

Industry

Executive

Executive

First

Fidelity

covered-

average

Life

(CAS

Life

jNY)_

Capital

Bankers

1980-1985

95~

824

1,021

844$

34~

1985-1990

66

82

35

139

1,685

1980-1990

223

1,578

1,273

1,917

2,294

Source:

Best's

Insurance

Reports

(Life/Health

Editions).

At

its

peak

in

1989,

Executive

Life

reported

$13.2

billion

in

assets

--more

than

21

times

its

size

in

1980.

Executive

Life

of

New

York

peaked

in

1988

at

$4

billion

in

assets,

more

than

17

times

its

1980

level.

First

Capital

also

experienced

rapid

growth,

with

assets

increasing

to

$4.7

billion

in

1989,

over

21

times

the

1980

level.

Unlike

the

other

three

insurers,

fidelity

Bankers

did

not

grow

rapidly

during

the

first

half

of

the

1980x.

Its

reported

assets

had

increased

34

percent

by

1985.

However,

in

late

1985

it

was

purchased

by

First

Capital

Holdings

Corporation

and

was

reporting

X4.1

billion

in

assets

by

1990

--about

24

times

its

1980

level.

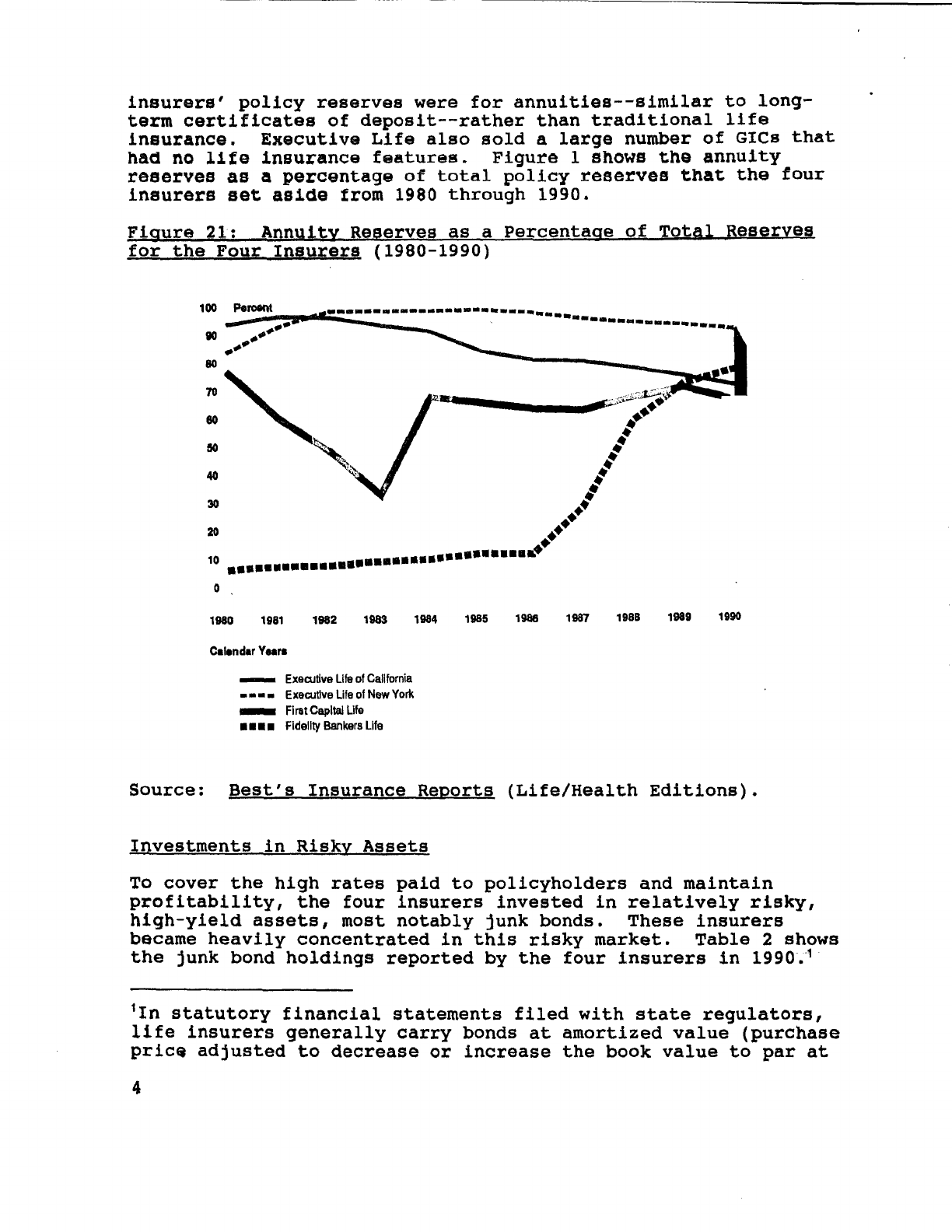

During

the

1980s,

the

four

insurers

grew

mainly

by

selling

high

-

yield

retirement

investment

products.

All

or

most

of

the

3

insures'

policy

r~~~rvea

were

far

annuities--~imil~r

to

long-

term

certificates

of

deposit

--rather

than

traditional

lifer

insurance.

Ex~cutiv~

Life

also

sold

a

large

number

of

GICs

th~~

had

no

life

insurance

features.

Figure

1

showy

the

annuity

reserves

as

a

percentage

of

tatai

policy

reserve

~riat

the

four

insurers

yet

aside

from

19$0

through

1990.

Fiq~re

21•

Annuity

Reserves

as

a

Percentage

of

Total

Reserves

for

the

Four

Insurers

(1980-1990}

t00

~~"'

90

80

70

BO

50

40

30

20

10

•/pA,M~~l~r~diwYfllY~A~~~~--

0

1980

1981

19$2

1983

1984

1985

1988

198'7

1986

1889

1990

Cd~nd~r

Yvan

~~

Executive

Life

of

California

-~

~.

Executive

Life

of

New

York

~~

Fist

Capital

Life

■~~■

Fidelity

Bankers

Lffe

Source:

Best's

Insurance

Reports

(Life/Health

Editions).

~r~vestments

in

Risky

Assets

To

cover

the

high

rates

paid

to

policyholders

and

maintain

profitability,

the

four

insurers

invested

in

relatively

risky,

high

-yield

assets,

most

notably

junk

bands.

These

insures

became

heavily

concentrated

in

this

risky

market.

Table

2

shows

the

junk

bond

holdings

reported

by

the

four

insurers

in

1990.'

'In

statutory

financial

statements

filed

with

state

regulators,

life

insurers

generally

carry

bands

at

amortized

value

(purchase

price

adjusted

to

decrease

or

increase

the

book

value

to

par

at

4

Table

2:

Junk

Sow

HQ~,~y

the

Four

Insur~re

a~

a

Pexc~n~a~e

of

Assets

in

1940

(Dollnre

in

billions)

Executive

Life

(CA)

X6.,4

63~

Executive

Life

(NY)

2.0

64

First

Capital

1.6

36

Fidelity

Bankers

1.5

40

Source:

Best's

Insurance

Reports

(1991

Life/Health

Edition).

The

four

insurers

did

not

have

had

adequate

statutory

reserves

against

their

bond

portfolios

to

cushion

against

potential

losses.

Under

statutory

accounting

rules,

the

maximum

reserve

required

ageinst

a

life

insurer's

junk

bond

holdings

is

10

to

20

percent.

2

Due

to

mounting

bond

losses,

the

Executive

Life

insurers'

reserves

against

future

loss

represented

about

1

percent

of

their

junk

bond

holdings.

As

a

result,

a

10

-percent

loss

on

their

junk

bond

holdings

-

would

have

wiped

out

the

reserves

and

net

worth

of

the

two

insurers.

Similarly,

a

10

-

percent

loss

on

junk

bonds

would

have

left

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers

seriously

undercapitalized.

Table

3

shows

the

Ensurers'

security

valuation

reserves

in

1990

as

a

percentage

of

their

junk

bond

holdings

and

the

percentage

loss

in

junk

bond

values

that

would

have

eliminated

the

insurers`

surplus

and

bond

reserves.

maturity

date).

Bonds

in

or

near

default

are

carried

at

the

lesser

of

amortized

or

market

value.

2

The

"mandatory

securities

valuation

reserve"

is

intended

to

buffer

surplus

from

losses

or

fluctuations

in

the

market

value

of

securities

held.

Higher

reserves

are

required

for

junk

bond

than

for

higher

quality

bonds

with

a

maximum

reserve

of

20

percent

for

defaulted

bonds.

The

security

reserve

may

be

accumulated

over

10

to

20

years.

fable

~

•

Band

Reserves

~n

1990

as

a

~ercenta~e

o~

Junk

Bonds

and

the

Percentage

Bond

Loss

to

Eliminate

Surplus

and

Reserve

Reserves

as

a

percent

of

Percent

loss

to

wipe

dunk

bonds

out

surplus

and

reserves

Executive

Life

(CA)

0.8~

8.3$

Executive

Life

(NY)

1.3

10.4

First

Capital

4.5

11.2

Fidelity

Bankers

3.6

11.7

Source:

Insurer

'

1990

annual

financial

statements

and

Best's

Insurance

Reports

(1991

Life/Health

Edition).

Public

awareness

of

the

risks

and

increasing

losses

associated

with

these

extensive

junk

bond

holdings

led

to

policyholder

runs

an

the

insurers.

FSrst

Executive

Corporation

--the

parent

of

the

Executive

Life

insurers

--announced

a

$847

million

charge

for

bond

defaults

and

losses

during

1989.

The

February

1990

failure

of

Drexel

Burnham

Lambert

exacerbated

the

collapse

of

the

junk

bond

market.

These

events

led

to

a

massive

run

on

Executive

Life

and

Executive

Life

of

New

York,

with

policyholders

withd=awing

a

total

of

about

~4

billion

in

1990.

According

to

regulators,

the

April

1991

takeovers

of

Executive

Life

and

Executive

Life

of

New

York

spurred

policyholder

runs

nn

junk

bond

laden

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers.

Dwindling

Surplus

To

bolster

their

statutory

surplus,

the

insurers

resorted

to

the

use

of

questionable

reinsurance

transactions

to

reduce

required

policy

reserves

on

their

balance

sheets.

They

also

received

surplus

infusions

and

loans

from

their

parent

holding

companies.

Statutory

surplus

is

a

measure

of

an

insurer's

solvency.

Under

statutory

accounting

practices,

an

insurer's

costs

of

selling

policies

--such

as

agent

sales

commissions

--are

charged

to

expenses

when

they

occur.

Because

most

premium

income

is

deferred

and

expenses

are

charged

off

immediately,

an

insurer's

surplus

shrinks

as

the

company

grows.

For

the

tour

insurers,

rapid

growth

had

the

effect

of

depleting

their

surplus

to

levels

that

were

much

lower

than

the

industry

as

a

whole.

Surplus

Relief

Reinsurance

All

four

insurers

relied

heavily

upon

reinsurance

to

relieve

the

strain

of

growth

on

their

surplus.

Under

a

reinsurance

contract,

the

original

insurer

transfers

or

"cedes"

to

another

insurer

(the

"reinsurer")

all

or

part

of

the

financial

risk

accepted

in

selling

policies

to

the

public.

The

reinsurer,

for

a

premium,

agrees

to

indemnify

or

reimburse

the

ceding

company

for

all

or

part~of

the

losses

that

the

latter

may

sustain

from

claims

it

6

r~c~iv~s.

In~ur~r~

routinely

use

reineuranc~

to

transfer

ri~k~

under

large

policies

in

excess

of

a

specified

retention.

Reinsurance

has

both

legitimate

and

illegitimate

use$.

It

is

a

legitimate

practice

in

the

life

insurance

industry

to

diversify

risks

and

reduce

the

surplus

drain

from

selling

new

policies.

A

ceding

company

obtains

surplus

relief

to

the

extent

that

it

can

reduce

its

required

policy

reserves

for

liabilities

transferred

to

reinsurers.

However,

reinsurance

can

also

be

used

to

mask

an

insurer's

true

financial

condition

by

artificially

inflating

its

surplus.

Some

financial

or

so-called

"surplus

relief"

reinsurance

transactions

transfer

little

or

no

risk

of

loss

to

the

reinsures.

These

transactions

distort

an

insurer's

financial

statement

by

decreasing

its

required

policy

reserves

and

thus

increasing

its

surplus,

even

though

the

insurer's

liability

remains

the

same.

Executive

Life,

Executive

Life

of

New

York.,.

and

First

Capital

relied

on

surplus

relief

reinsurance

to

artificially

inflate

their

surplus.

3

These

insurers

were

paying

reinsurance

premiums

for

the

benefit

of

claiming

credit

on

their

statutory

financial

statements,

even

though

the

financial

reinsurers

were

not

liable

to

pay

any

claims.

For

example,

Executive

Life

paid

$3.5

million

to

reinsurers

in

exchange

for

reserve

credits

of

$147

million

in

1990;

however,

the

reinsurers

had

-no

contractual

liability

to

reimburse

any

of

the

~l

billion

in

claims

supposedly

covered

by

the

reinsurance

treaties.

Executive

Life

was

not

reinsuring

against

the

risk

of

loss

due

to

policyholder

claims;

the

company

was

renting

surplus.

Without

surplus

relief

reinsurance

and

the

commensurate

increase

in

spurious

surplus,

the

Executive

Life

insurers

would

have

been

insolvent

as

early

as

1983.

Suralus

Infusions

During

the

1980s,

all

four

insurers

also

received

millions

of

dollars

in

surplus

aid

from

their

parent

holding

companies.

Without

surplus

infusions

from

Executive

Life

to

its

New

York

subsidiary

and

from

First

Executive

to

the

California

company,

both

Executive

Life

insurers

would

have

been

insolvent

in

1986.

Although

these

infusions

allowed

the

insurers

to

meet

minimum

capital

requirements,

surplus

aid

represents

a

temporary

solution

that

does

not

correct

underlying

causes

of

capital

deficiencies.

The

continuing

need

for

surplus

infusions

demonstrated

the

inherent

capital

inadequacies

of

the

four

insurers.

In

addition

to

direct

infusions

of

cash,

the

surplus

aid

also

took

the

form

of

loans

from

the

parent

holding

companies

to

the

3

We

could

not

obtain

data

on

surplus

relief

reinsurance

for

Fidelity

Bankers

because

the

regulatory

examination

report

is

not

yet

available.

7

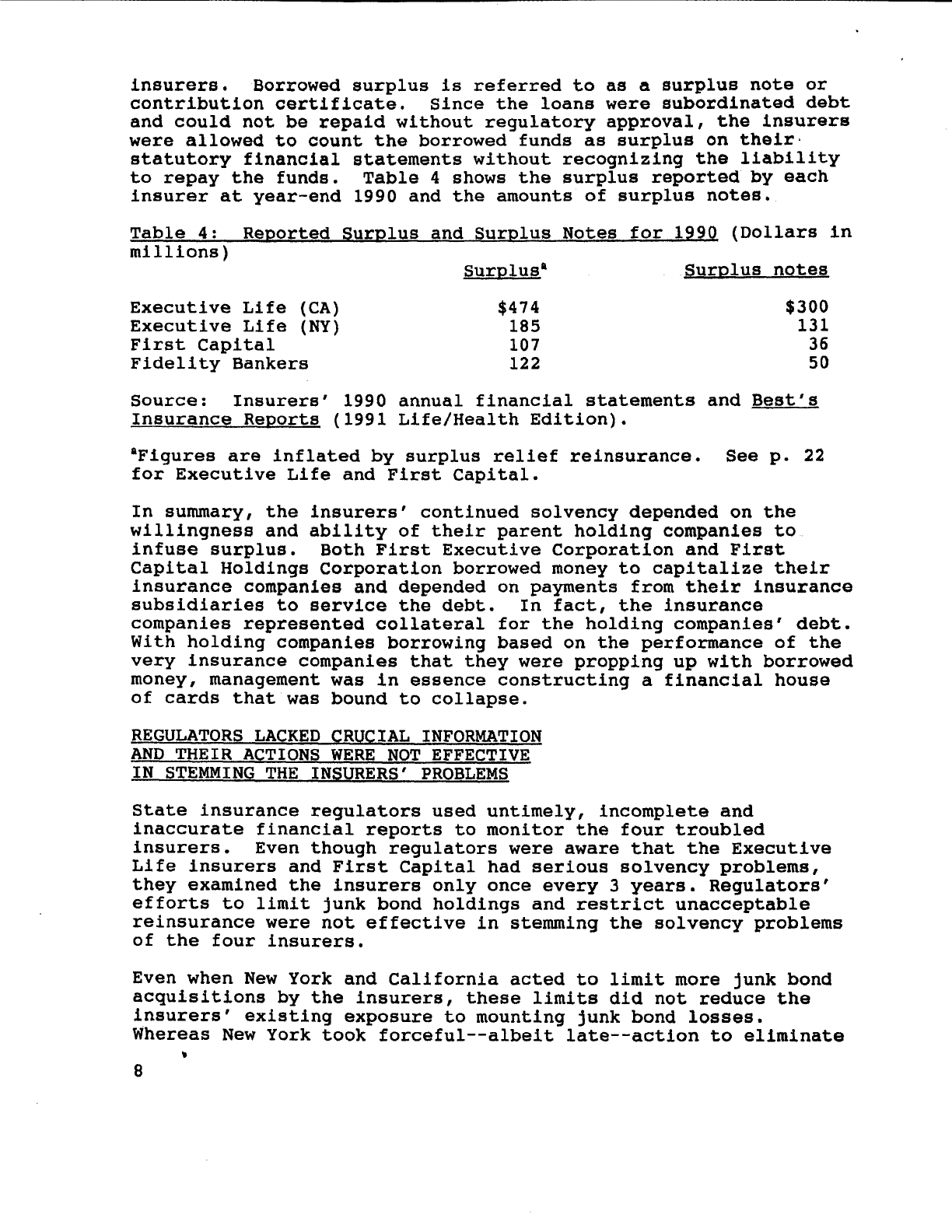

insurers.

Sorrowed

surplus

is

referred

to

as

a

surplus

note

or

contribution

certificate.

Since

the

loans

were

subordinated

debt

and

could

not

be

repaid

without

regulatory

approval,

the

insurers

were

allowed

to

count

the

borrowed

funds

as

surplus

on

their•

statutory

financial

statements

without

recognizing

the

liability

to

repay

the

funds.

Table

4

shows

the

surplus

reported

by

each

insurer

at

year-end

1990

and

the

amounts

of

surplus

notes.

Table

4:

Reported

Surplus

and

Surplus

Nates

for

1990

(Dollars

in

millions)

Surplus

°

surplus

notes

Executive

Life

(CA)

$474

$300

Executive

Life

(NY)

185

131

First

Capital

107

36

Fidelity

Bankers

122

50

Source:

Insurers'

1990

annual

financial

statements

and

Best`s

Insurance

Reports

(1991

Life/Health

Edition).

°Figures

are

inflated

by

surplus

relief

reinsurance.

See

p.

22

for

Executive

Life

and

First

Capital.

In

summary,

the

insurers'

continued

solvency

depended

on

the

willingness

and

ability

of

their

parent

holding

companies

to.

infuse

surplus.

Both

First

Executive

Corporation

and

First

Capital

Holdings

Corporat~an

borrowed

money

to

capitalize

their

insurance

companies

and

depended

on

payments

from

their

insurance

subsidiaries

to

service

the

debt.

In

fact,

the

insurance

companies

represented

collateral

for

the

holding

companies'

debt.

With

holding

companies

borrowing

based

on

the

performance

of

the

very

insurance

companies

that

they

were

propping

up

with

borrowed

money,

management

was

in

essence

constructing

a

financial

house

of

cards

that

was

bound

to

collapse.

REGULATORS

LACKED

CRUCIAL

INFORMATION

AND

THEIR

ACTIONS

WERE

NOT

EFFECTIVE

IN

STEMMING

THE

INSURERS'

PROBLEMS

State

insurance

regulators

used

untimely,

incomplete

and

inaccurate

financial

reports

to

monitor

the

four

troubled

insurers.

Even

though

regulators

were

aware

that

the

Executive

Life

insurers

and

First

Capital

had

serious

solvency

problems,

they

examined

the

insurers

only

once

every

3

years.

Regulators'

efforts

to

limit

junk

bond

holdings

and

restrict

unacceptable

reinsurance

were

not

effective

in

stemming

the

solvency

problems

of

the

four

insurers.

Even

when

New

York

and

California

acted

to

limit

more

junk

bond

acquisitions

by

the

insurers,

these

limits

did

not

reduce

the

insurers'

existing

exposure

to

mounting

junk

bond

losses.

Whereas

Hew

York

took

forceful

--albeit

late

--action

to

eliminate

8

reinsurance

problems

for

Executive

Life

of

New

York,

California

practiced

regulatory

forbearance

for

Executive

Life

and

First

Capital.

In

part,

California

regulators'

efforts

to

monitor

Executive

Life

were

undermined

by~the

in'surer's

failure

to

comply

with

state

holding

company

laws.

Regulators'

Information

Was

Neither

Timely,

Complete,

Nor

Accurate

State

regulators

did

not

have

timely,

complete

and

accurate

information

to

monitor

the

four

troubled

insurers.

Without

timely

financial

statements

that

fairly

present

an

insurer's

true

condition,

regulators

cannot

act

quickly

to

resolve

problems.

We

have

identified

a

number

of

areas

where

regulators

lacked

crucial

information

about

the

four

troubled

insurers.

First,

financial

statements

filed

in

accordance

with

statutory

accounting

practices

did

not

fairly

reflect

the

four

insurers'

true

financial

condition.

For

example,

as

I

previously

discussed,

reported

surplus

was

artificially

inflated

by

surplus

relief

reinsurance.

However,

the

financial

statements

did

not

provide

information

necessary

for

regulators

to

distinguish

between

valid

reinsurance

and

this

statutory

accounting

gimmick.

In

addition,

statutory

financial

statements

for

1989

filed

by

the

Executive

Life

insurers

did

not

reflect

known

losses

on

their

junk

bond

holdings.

The

two

insurers

wrote

off

only

$335

million

in

losses

and

did

not

even

disclose

$435

million

in

additional

impairments.

Second,

an

insurance

holding

company

is

not

required

to

file

consolidated

financial

statements

based

on

statutory

insurance

accounting.

Such

information

would

be

useful

in

assessing

interaffiliate

transactions

and

the

overall

financial

condition

of

the

holding

company

system.

Insurance

regulators

instead

use

10-K

reports

for

publicly

traded

insurance

holding

companies.

However,

the

10-K

report

is

based

on

generally

accepted

accounting

principles,

which

may

be

more

or

less

restrictive

than

statutory

accounting.

Third,

regulators

relied

on

infrequent

field

examinations

to

verify

financial

data

reported

by

the

insurers

and

detect

solvency

problems.

Such

examinatipns

were

done

about

once

every

3

years

and

took

months

or

even

years

to

complete.

4

Appendix

I

shows

the

time

lags

between

the

examinations

of

the

four

insurers

and

reporting

delays.

California

and

New

York

regulators

waited

until

1990

in

the

triennial

schedule

to

examine

the

Executive

Life

companies

again,

even

though

regulators

had

identified

4

Hereafter,

the

year

of

the

examination

refers

to

the

year

under

review,

not

the

year

in

which

the

examination

took

place.

D

continuing

prabl~ms

in

the

1986

and

1987

examinations.

For

example:

--

New

York

regulators,

in

their

1980

examination

of

Executive

Life

of

New

York,

found

internal

control

problems,

including

a

blurring

of

the

separate

operating

identities

of

Executive

Life

of

New

York

and

its

parent

Executive

Life

as

well

as

improper

allocation

of

income

and

expenses.

The

1983

examination

of

Executive

Life

of

New

York

revealed

more

control

deficiencies,

including

failure

to

maintain

proper

records.

The

1986

examination

found

that

control

deficiencies

identified

in

the

earlier

examinations

still

had

not

been

corrected.

--

California

regulators,

in

their

1983

examination

of

Executive

Life,

found

problems

with

poor

record

keeping

and

unacceptable

reinsurance.

The

1986

examination

of

Executive

Life

revealed

continuing

problems

with

reinsurance.

In

fact,

California

regulators

found

the

problems

to

be

so

serious

that

they

extended

the

examination

to

1987.

Fourth,

regulators

did

not

get

financial

information

early

enough

to

identify

and

react

to

the

rapid

deterioration

that

these

insurers

experienced

in

1990.

For

example,

in

January

1990

when

First

Executive

Corporation

announced

the

massive

bond

losses

and

policyholders

began

a

run

on

the

Executive

Life

insurers,

the

last

complete

financial

statements

available

to

state

regulators

were

already

more

than

a

year

old;

regulators

did

not

receive

the

1989

annual

financial

statements

until

March

1990.

Even

quarterly

statements

were

not

timely

enough

to

keep

the

regulators

up

to

date.

Starting

in

March

1990,

the

troubled

Executive

Life

insurers

provided

monthly

and

even

weekly

reports

so

that

the

regulators

could

track

the

policyholder

runs

and

mounting

bond

losses.

5

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers

were

required

to

provide

monthly

reports

in

early

1491.

Finally,

the

states

did

not

keep

each

other

informed

about

solvency

problems,

despite

their

interdependence

in

monitoring

the

troubled

insurers.

For

example,

when

California

regulators

were

doing

their

1987

examination

of

Executive

Life,

the

most

current

information

available

from

New

York

about

the

insurer's

major

subsidiary

was

more

than

3

years

old.

New

York

regulators'

report

on

their

1986

examination

of

Executive

Life

of

New

York

was

not

provided

to

other

state

regulators

until

1990.

In

addition,

Minnesota

and

New

Jersey

regulators

said

that

their

states

had

trouble

getting

information

about

Executive

Life

from

California.

In

early

1990,

NAIC

formed

a

multistate

working

S

The

Executive

Life

insurers

provided

weekly

reports

of

daily

surrender

activity,

bimonthly

reports

of

insurance

operations,

and

monthly

reports

of

cash

€low

and

investment

activity.

10

group

to

help

di~~minat~

financial

information

and

gtatu~

reports

to

other

atat~s

where

the

Executive

Life

insurers

were

licensed.

'

Regulators

Lac

~d

~nform~tion

to

Evaluate

and

Authar~ty

to

Limit

Junk

Bond

Holdings

Regulators

also

had

inadequate

information

about

the

quality

of

the

four

insurers`

bond

holdings

and

inadequate

regulatory

authority

to

limit

~u~k

bond

holdings

during

the

period

that

the

four

insurers

built

up

their

portfolios.

Before

1990,

NAIC's

bond

rating

system

did

not

fully

disclose

an

insurer's

holdings

of

noninvestment

grade

bonds.

NAIL

acknowledged

that

its

old

system

counted

some

junk

bonds

as

investment

grade,

but

its

new

classification

system

is

intended

to

better

reflect

the

quality

of

an

insurer's

bond

portfolio.

Under

NAIC's

old

rating

system,

First

Executive

reported

in

1989

that

35

percent

of

its

bonds

were

investment

grade.

However,

according

to

Standard

&

Poor's

rating

system,

less

than

8

percent

of

the.Executive

Life

companies'

bond

portfolios

in

1989

was

investment

grade.

Not

only

did

regulators

not

know

the

extent

of

the

insurers'

junk

bond

holdings,

but

they

did

not

know

what

those

bonds

were

worth.

Regulators

knew

that

the

market

values

for

the

junk

bonds

were

less

than

the

amortized

values

in

the

insurers'

1989

statutory

financial

statements.

According

to

the

chairman

of

NAIC's

working

group,

regulators

needed

to

know

which

bonds

might

default

and

how

much

the

insurers

would

lose.

Because

the

California

department

did

not

have

the

expertise

to

evaluate

Executive

Life's

portfolio,

in

early

1990

it

had

to

get

an

independent

actuarial

firm

to

assess

whether

the

insurer's

assets

could

support

its

liabilities.

The

actuarial

firm,

however,

relied

on

optimistic

assumptions

about

default

rates

and

investment

income

provided

by

Executive

Life;

actual

bond

losses

surpassed

even

the

worst

-case

scenario

in

the

actuarial

studies.

Regulators

did

not

request

an

independent

evaluation

of

the

default

risk

for

Executive

Life's

portfolio

until

February

1991.

Even

if

they

had

accurate

and

up-to-date

information,

regulators

dfd

not

have

specific

statutory

or

regulatory

authority

to

limit

junk

bond

holdings.

In

1987,

New

York

limited

insurers'

holdings

of

junk

bonds

to

20

percent

of

assets.

However,

the

New

York

regulation

did

not

correct

Executive

Life

of

New

York's

problems

because

the

insurance

company

was

grandfathered

and

did

not

have

to

divest

of

junk

bond

holdings

in

excess

of

the

cap.

In

1990,

Executive

Life

of

New

York's

junk

bond

holdings

were

64

percent

of

assets

and

represented

962

percent

of

the

insurer's

reported

surplus

and

bond

reserves.

Even

though

California

did

not

adopt

investment

limits

on

junk

bonds

until

1991,

Executive

Life

agreed

in

1990

not

to

acquire

more

funk

bonds.

Virginia

has

a

bill

pending

to

limit

insurer$`

11

junk

bond

holding

.

In

Junes

1991,

NAIL

adapted

a

model

regulation

limiting

an

in~urer'a

investment

in

medium

and

lower

grade

bonds

to

20

percent

of

itg

assets.

According

to

NAIC,~16

states

had

set

specific

limits

on

holdings

of

high

-yield,

high

-

risk

bonds

as

at

November

1991.

Regulators

Tried

to

Curb

Re~n~u~~nce

P~obl~ms

Until

the

early

1980a,

surplus

relief

reinsurance

was

largely

unregulated.

In

its

1980

examin8tion,

New

York

found

that

Executive

Life

of

New

York's

surplus

would

have

been

nearly

depleted

without

surplus

relief

reinsurance.

By

the

1983

exam,

surplus

relief

reinsurance

exceeded

the

insurer's

surplus.

In

1985,

New

York

issued

a

regulation

prohibiting

credit

for

surplus

relief

reinsurance

that

did

not

transfer

risk

to

the

reinsurer

and

allowed

3

years

to

write

off

such

existing

financial

reinsurance.

In

the

1986

exam,

New

York

found

that

Executive

Life

of

New

York's

problems

with

unacceptable

surplus

relief

reinsurance

persisted

and

that

its

reinsurance

program

was

rife

with

internal

control

deficiencies.

In

198$,

New

York

disallowed

X148

million

in

reinsurance

credits

on

the

insurer's

1986

financial

statement.

Further,

New

York

Fined

the

Executive

Life

of

New

York

;250•,000

and

required

three

officers

to

~esign.

g

According

to

New

York,

the

insurer

no

longer

had

any

surplus

relief

reinsurance.

As

early

as

the

1983

field

examinations,

California

detected

certain

financial

reinsurance

arrangements

that

did

not

transfer

risk

and

which

were

not

in

compliance

with

state

law.

However,

California

allowed

3

years

for

Executive

Life

and

First

Capital

to

write

off

the

unacceptable

surplus

relief

reinsurance.

In

the

1986

examination

of

First

Capital

and

the

1987

examination

of

Executive

Life,

California

found

that

both

insurers

had

entered

into

even

more

surplus

relief

reinsurance

arrangements

to

support

their

explosive

growth.

In

contrast

to

the

forceful

--albeit

late

--actions

taken

by

the

New

York

regulators,

California

again

did

not

immediately

disallow

the

unacceptable

surplus

relief

reinsurance

but

instead

let

the

insurers

amortize

the

amounts.

California's

bulletin

restricting

surplus

relief

reinsurance

was

not

issued

until

1989

and

even

then

granted

another

3

-year

write-

off

period.

As

a

result,

Executive

Life

still

had

X147

million

in

unacceptable

surplus

relief

reinsurance

in

1990

while

First

e

These

three

officers

continued

to

work

for

Executive

Life

in

California

after

their

dismissals

from

New

York.

'Executive

Life

did

have

$180

million

in

surplus

relief

reinsurance

disallowed

in

the

1987

examination

due

to

defective

lettgrs

of

credit

from

an

off

-shore

reinsurer.

12

Capital

had

X65

million.

Many

states

still

have

nat

acted

to

restrict

use

of

this

statutory

accounting

gimmick.

e

~,

,

.,

,

Holding

Companies

Are

a

Regulatory

Blind

Spot

State

insurance

regulators

have

limited

capability

to

evaluate

and

control

an

insurer's

relationships

with

its

holding

company

and

affiliated

entities.

State

holding

company

laws

rely

on

insurer

disclosure

to

monitor

affiliated

relationships,

and

some

states

have

prior

regulatory

approval

requirements

to

prevent

abusive

transactions.

Regulators

cannot

effectively

assess

interaffiliate

transactions

if

the

insurer

fails

to

report

either

the

identity

of

its

affiliates

or

the

transactions.

Except

for

infrequent

field

examinations,

regulators

have

no

way

to

verify

the

insurer's

reported

information.

Interaffiliate

transactions

Can

mask

an

insurer's

true

condition,

and

improper

transactions

with

affiliates

have

caused

previous

life

insurer

failures.

g

We

do

not

know

to

what

extent

interaffiliate

dealings

may

have

contributed

to

the

four

insurance

failures

in

part

because

reports

of

the

latest

regulato=y

examinations

by

New

York

and

Virginia

are

not

yet

available.

However,

on

the

basis

of

our

preliminary

work

in

California,

we

found

that

Executive

Life's

failure

to

comply

with

state

holding

company

laws

undermined

California's

solvency

monitoring

efforts.

Executive

Life

repeatedly

failed

to

report

and

get

approval

for

transactions

with

its

parent

and

affiliates.

As

a

result,

California

regulato=s

could

not

effectively

assess

the

impact

of

those

transactions

on

the

insurer's

solvency

and

protect

policyholder

interests.

For

example,

--

Executive

Life

did

not

get

California's

approval

before

it

made

a

$131

million

surplus

loan

to

its

New

York

subsidiary

in

1987.

The

transaction

removed

cash

from

Executive

Life

when

the

insurer

was

already

seriously

troubled.

That

money

will

not

be

available

to

pay

policyholders

of

the

Cali,~ornia

~In

1986,

NAIC

adopted

a

model

regulation

do

life

reinsurance

agreements

based

on

New

York's

law.

As

of

October

1991,

only

19

states

--including

Virginia

--had

acted

to

adopt

the

model.

Since

this

model

is

required

for

NAIC

accreditation,

NAIL

expects

more

states

may

adopt

surplus

relief

reinsurance

regulations.

9

Abusive

interaffiliate

transactions

caused

the

Baldwin

-United

failure

--the

largest

life

insurer

failure

before

the

Executive

Life

takeovers.

According

to

state

regulators,

the

parent

holding

company

milked

the

insurance

subsidiaries

to

service

its

own

debt.

13

inaur~r

unlee~

New

York

lets

the

s~ubeidiary

relay

Executive

Lite.

--

Executive

Life

shifted

X789

million

of

its

dunk

bond

holdings

to

unreported

affiliates

in

1988.

Th0

tr8n8aCtlon

had

the

~gteCC

of

reducing

the

insurer's

bold

reserves

~Ad

inflating

its

surplus

by

about

X109

million,

thus

absauring

ita

true

financial

condi~ion.

10

--

Executive

Life's

1990

annual

statutory

statement

did

not

identify

36

aff111ates

and

subsidiaries,

even

though

the

insurer

had

invested

in

many

of

those

affiliated

companies.

CONCLUSIONS

The

reckless

growth

pursued

by

these

four

insurers

was

supported

by

questionable

business

strategies.

The

four

insurers

were

heavily

invested

in

poor

quality

assets.

They

relied

on

phony

financial

reinsurance

and

money

borrowed

£rom

their

parents

to

artificially

inflate

their

surplus

and

mask

their

true

financial

conditions.

Without

surplus

relief

reinsurance

and

borrowed

surplus,

the

two

Executive

Life

insurers

would

have

been

insolvent

in

the

early

1980s

while

First

Capital

and

Fidelity

Bankers

would

have

been

undercapitalized.

Despite

untimely,

incomplete,

and

inaccurate

information,

state

regulators

were

aware

of

the

troubled

conditions

of

the

four

insurers

before

the

companies

were

taken

over

but

did

not

take

effective

action

to

stem

the

financial

deterioration

of

the

companies

or

minimize

losses.

Only

after

the

insurers

hemorrhaged

from

policyholder

runs

did

state

regulators

move

to

take

them

over.

As

I

mentioned

at

the

outset

of

my

remarks,

we

are

still

reviewing

the

performance

and

capabilities

of

the

state

regulators,

so

my

observations

today

do

not

represent

our

final

assessment.

This

completes

my

prepared

statement.

I

would

be

pleased

to

answer

any

questions.

1°

In

1990,

California

regulators

made

Executive

Life

reverse

the

bond

transactions

and

restate

its

financial

statements.

14

State

insurance

departm~nta

generally

do

on

-site

field

examinatiana

of

inaurer~

every

3

to

5

years,

though

a

troubled

insurer

could

be

examined

more

frequently.

The

state

of

domicile

leads

the

examination,

and

examiners

from

other

states

in

which

the

insurer

is

licensed

can

participate.

After

the

examiners

finish

their

fieldwork,

they

submit

the

report

to

the

heads

of

the

insurance

departments

participating

in

the

examination

--the

report

date.

The

company

examined

then

has

the

opportunity

to

review

the

report

and

submit

comments.

The

final

report

is

then

distributed

to

all

states

where

the

company

is

licensed

and

filed

as

a

public

document

--the

filing

date.

Executive

Life,

Executive

Life

of

New

Fidelity

Bankers

were

examined

about

were

the

examinations

infrequent,

but

even

years.

Table

I.1

includes,

for

four

insurers,

the

period

covered

by